‘Seldom any splendid story is wholly true.’

– Samuel Johnson

One of the most interesting things in studying the documentary field is the complex relationship between fiction, nonfiction and documentary as categories, and how they overlap. A commonsense assumption, for example, appears to be that any use of narrative or dramatisation is somehow equal to fictionalising, and that this effectively negates any documentary worth that a film might have. As noted in the previous chapter however, central to an understanding of ‘documentary’ is the spectatorial activity of actually interpreting the material, something that Dai Vaughan has discussed as the ‘documentary response’ (1999), and Noël Carroll has suggested comes under the rubric of a system of ‘indexing’ (1996). And, as will be argued in this chapter via a series of case studies, the relationship between fiction and nonfiction is increasingly what Bill Nichols (1994) would describe as a ‘blurred boundary’. As we shall see (in this chapter and, subsequently, in chapter three) use of a narrative or even certain supposedly ‘fictional’ techniques – such as reconstruction or re-enactment – is by no means out of bounds for the documentarist. Indeed, some of the more interesting work in the area has always been that which explores the boundary between these apparently ‘separate’ modes.

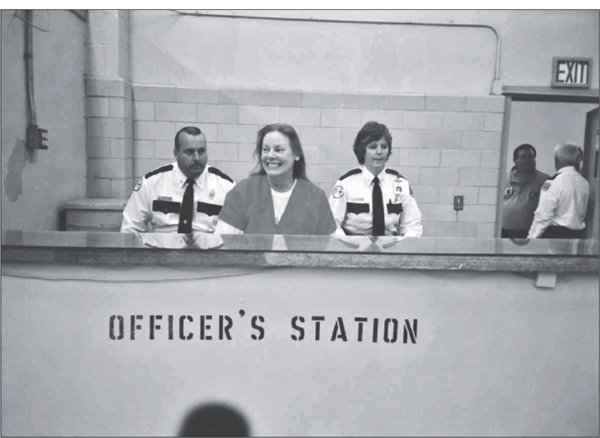

In chapter three we shall specifically examine the different ways that various films have used re-enactment and reconstruction with a view to mapping how documentaries engage with history and constructions of the past. This chapter will first of all offer an outline of some the critical debates relating to drama and documentary as seemingly separate, yet complexly overlapping modes. It will then move on to examine how some specific examples tell their stories, from what perspective, and what consequences this has for their perceived status as ‘documentary’. The inter-relationships between drama documentary, documentary drama (and all the variations on these) have always been complex, and they have become much more so in recent times. One of the key areas to be examined will be the ways in which actors perform the role of real people in reconstructed or re-enacted scenes, and, more contentiously, how real people/non-actors ‘play themselves’ in some way. These modalities of performance clearly strike right to the heart of a ‘traditional’ (and some would say hopelessly outdated) ‘documentariness’ in the sense that they foreground the hybrid and uncertain nature of much contemporary documentary output. In other words, our ways of understanding what is going on in current documentary production (and criticism) needs to take on board the increasingly blurred boundary between fiction and nonfiction, acting and simply being. The final part of the chapter will examine what may be seen as one of the more interesting recent phenomena in documentary, the Aileen Wuornos affair. There are two Nick Broomfield documentaries about Wuornos and the strange people who associated with her in her last years, but rather than simply offering a reading of these documentaries, here we shall explore the relationship between these films and the other dramatised/fictionalised versions of the Wuornos story. Rather than seeing the documentaries as the more ‘authentic’ and ‘truthful’ version of ‘what really happened’, this area is opened up so that the complex web of meanings created by all texts pertaining to the Wuornos story can be seen as part of how we understand it; there are issues around fiction and reality, performance and deception that can usefully be interrogated by looking at the relationships between these different versions of the ‘same’ story.

Drama and documentary as modes

Derek Paget (1990; 1998) has done much interesting work that attempts to tease out some of the intricacies of the relationship between ‘documentary’ and ‘drama’ as terms. Paget uses a ‘wordsearch’ approach, stating that ‘the phrases, compound nouns and noun-coinages in question [when discussing "drama" and "documentary" and their inter-relatedness] are drawn mainly from four root words – "documentary", "drama", "fact" and "fiction"’ (1998: 90–1). He then goes on to map a tentative list of terms and phrases that are in common usage (some more common than others). For example, there are those terms that use both ‘drama’ and ‘documentary’, but lead off with the former – so we have ‘dramatised documentary’, ‘drama documentary’, ‘drama-documentary’ and ‘dramadoc’. Paget also states that ‘dramatic reconstruction’ can be included in this list as the term reconstruction identifies ‘a documentary claim’ (1998: 91). Next, there are those terms that combine the same two terms but lead with ‘documentary’: ‘documentary drama’, ‘documentary-drama’, ‘docudrama’ or ‘documentary-style’ all fall into this section. Lastly, there are those terms that do not necessarily directly use either ‘drama’ or ‘documentary’, but play on some sense of ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ to draw out much the same tension as the other categories: ‘faction’, ‘fact-based drama’, ‘based on fact’, or ‘based on a true story’ are the key examples here.

There are, of course, considerable problems with all of these terms in that they are often used so interchangeably as to lose specificity in their meaning. Again, as Paget makes clear, the key confusion is between those terms that use ‘drama’ and ‘documentary’ as their foundations – it is commonplace to see the same film or programme referred to as both a ‘drama documentary’ and a ‘documentary drama’, as if there is no difference between them. Is there a difference? Paget’s contention that we think about where the relative emphasis lies is certainly a useful one:

It is tempting to regard the phrases … as always weighted towards the second word. Thus, just as ‘dramatic’ in the phrase ‘dramatic documentary’ acts as an adjective modifying the noun ‘documentary’, so ‘drama documentary’ is a documentary treated dramatically. But ‘drama-documentary’ claims a balance in which, perhaps, both will be equally present. (1998: 93)

Although this is useful up to a point, the problem remains of how we define when something is being ‘treated dramatically’; this is especially problematic now that we have a range of hybridised documentary output that has moved beyond the apparently simpler demarcations of ‘drama’ and ‘documentary’ (and these boundaries were never that clear-cut in the first place). These new hybrids (or what Paget has referred to as ‘not-docs’ in a work-in-progress article (2002)) are ones that deliberately flaunt or distort their relative use of ‘documentary’, ‘drama’, ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ to the extent that the viewer is less than certain as to what they are watching.1 Rather than the clear-cut, easily-identifiable modes of conventional documentary – real people in real situations – these texts tend to use adapted conventions – real people in reconstructions, actors playing real people in documentary re-enactments – in order to make their points. These (and other) shifts in documentary signification have led John Corner (2000) to talk tentatively of a ‘post-documentary’ era, where hybridisation and what he identifies as a tendency towards ‘documentary as diversion’ are the main driving forces. As with any impulse towards using ‘dramatised’ forms (reconstructions and the like) there are always very good reasons for building a documentary around reconstructed or re-enacted material. Either there is no ‘direct’ record of the events that can simply be drawn into the documentary context – this is the case with events from history when no cameras were present – or there are issues around anonymity or other problems with access that mean that reconstruction is one of the only options available.

Re-enacting the real: the performing of real-life scenarios

In her discussion of an edition of the BBC current affairs programme Panorama about the serial killer Dr Harold Shipman (Dr Shipman: The Man Who Played God, 2000, UK) – a programme that made extensive use of dramatised reconstructions of Shipman’s murders – Catherine Bennett (2000) tends to overstate some of the issues and problems relating to reconstruction, concluding that it is a completely invalid strategy: ‘Acknowledged reconstructions do not deceive … but they short-change us, deal in a currency inferior to the truth.’ Increasingly, documentarists are using techniques that clearly fall within the boundaries of ‘reconstruction’, but they are doing so in a way that is more complex than Bennett appears to allow, as she sees all reconstruction as essentially fictional. A key factor for consideration in documentary and non-fiction is of course that the events and persons depicted exist (or did exist) in the real world of actuality. Whereas in a fiction film, the events and persons are precisely that – fictional or made up. There are some interesting ways in which these apparently very simple demarcations are complicated, however. First and foremost, as sketched out above, we can talk of the various types of ‘dramatised’ documentary, where ‘drama’ and ‘documentary’ as modes are perceived to play off one another in some shape or form. These distinctions between documentary, drama-documentary and documentary-drama (and all the various points in between) are interesting and have been discussed at some length elsewhere. The immediate interest here is to examine some of the ways that recent film and programme makers have engaged with the notion of representing apparently real-world events, but do so by using dramatised forms of reconstruction and performance. The matter, as with much these days in the realm of documentary, is far from cut and dried.

In Tina Goes Shopping (Penny Woolcock, 1999, UK) and its sequel Tina Takes a Break (Penny Woolcock, 2001, UK) the events depicted take place on an impoverished Leeds housing estate. The film begins with a ‘continuity announcer’-style voiceover, speaking over a montage of split-screen scenes from the film itself. The voice explains Woolcock’s working methods and places the events we are about to see in some sort of documentary context:

She spent the next twelve months getting to know the inhabitants of some of the toughest estates in Leeds. She collected accounts of real events witnessed by the characters in their own lives and with them she shaped a drama. In the film, the residents improvise the story in their own words; no one is playing themselves, but it’s a world they know only too well.

The film is an improvised, highly naturalistic drama based on stories that are purported to have actually happened. As a caption says just after the opening sequence, ‘This is a drama inspired by true stories’. What is interesting here is how such a documentary drama format gives us access to material that we would not otherwise see. The main example here is Tina herself (played by Kelly Hollis). The eponymous character runs what she calls a ‘shopping service’: she takes orders from her friends and neighbours and then pilfers the items on a shoplifting spree. We see her doing this and freely admitting to it in a way that would not happen in a conventional documentary. For example, in one of the shoplifting scenes, we see Tina removing security tags from items of clothing she is about to steal. As she does this, she says to the camera, ‘The difference between "grafting" and "grafters" is that this is grafting – what you have to do – and grafters go out to work legally.’ There are some similar voiceovers or frank straight-to-camera admissions by other characters in the film – Aaron, Tina’s crack-addict boyfriend, or Don, her drug-dealing father – people admitting to things in a way that they never would in a conventional documentary.

Clearly then, these films are not ‘documentary’ in a straightforward sense of the term, as they involve people ‘acting’ and improvising, playing characters other than themselves. However, there is an argument that all documentary (and, indeed, all social interaction) involves people ‘acting’ in some sense of the term, so the distinction is arguably a matter of degree rather than us talking about completely different things. It is certainly the case that all manner of reality TV programmes rely on participants with a highly developed sense of performance. For example, the makers of a docu-soap will actively seek out flamboyant ‘characters’ in the (undoubtedly correct) belief that it will boost ratings. A programme such as Big Brother similarly relies on the contestants being ‘entertaining’ and playing to the cameras, juxtaposed with the more confessional/video diary conventions of the diary-room sequences. At the time of writing Makosi, a contestant in Big Brother 6, has been given several ‘secret missions’ by Big Brother, where she has had to lie, cheat and steal from fellow housemates. This has led to inevitable arguments and accusations that she is ‘not being herself’; another housemate has even entertained thoughts that Makosi may be a ‘mole’, placed in the house by Big Brother. The point of this is that the issues of performance and deception that are played out in these Big Brother scenarios are something that are central to a great deal of recent factual programming and documentary hybrids. In certain cases – for example, the infamous case of Carlton TV’s programme The Connection (1996), which included certain scenes of drug dealing that were dramatic reconstructions, but were passed off by the programme makers as the real thing captured then and there – the audience has been duped, pure and simple. But in other cases, we are seeing something more complex and nuanced than simple out-and-out ‘deception’. The fact that we are watching actors performing in a reconstruction is more often than not flagged up, and the wider questions being asked here are therefore to do with the status of ‘performance’ in contemporary factual television and filmmaking.

That aside, we need to think carefully about the status of films like Tina Goes Shopping. They ‘document’ a real, social reality in an utterly compelling way, and reveal things about their respective social contexts and characters that a ‘conventional’ documentary would arguably never be able to. The difficulty is that if these films are rejected out of hand as unable to usefully ‘document’ an aspect of reality, simply because they are a kind of improvised drama, then certain aspects of reality will never adequately be represented. It is the ability of such films as Tina Goes Shopping to show the reality of certain parts of society from ‘within’, as it were; that is their strength.

Another key example of this tendency was an edition of Panorama on the children of drug addicts, The Invisible Kids (2004, UK). All of the words were spoken by actors, yet the testimony given was drawn directly, word for word, from that given by real children living with this problem. Similarly, in the Channel 4 film Pissed on the Job (2004, UK), we were given detailed glimpses into the lives of some ‘high-functioning alcoholics’ (that is, people who are addicted to alcohol but manage to hold down responsible jobs). Here we have the real testimony of real people talking about their problem. The only way one could do this in a conventional documentary is to use the ‘silhouette’ technique, and/or disguise the voice of the person, such are the negative connotations for someone in such a position being an alcoholic. Such a technique, used for an entire film, might be deemed to be problematic for the filmmakers (as it would be a turn-off for the viewers). So, we have actors playing the roles, shot in a highly naturalistic style, interspersing direct-to-camera interviews (with the actor-as-alcoholic talking to an off-camera interviewer) with apparent reconstructions of events from their lives.

In all of the above examples, we clearly are being asked to take ‘as documentary’ something that is ‘performed’ by actors (in the case of Tina Goes Shopping, they are real people/non-actors, but they are playing roles). This is not to imply that we are duped (though this may of course be the case), but it is to stress that these films actively play upon the ‘uncertainty’ of the images and sounds they contain. Some commentators might simply dismiss them as out-and-out dramas, fabulations, but apart from anything else, they offer us access to parts of the real world we might not otherwise see (at least not in the depth and detail afforded us here). So some serious thought needs to be given to the truth status of what we see and hear in these films. This notion of how such acted dramas can have a documentary or ‘truth’ value is something returned to below via the discussion of the various versions of the Aileen Wuornos story.

Returning to the distinctions mapped out above, we cannot say that the stories told in Pissed on the Job or Tina Goes Shopping are ‘fictional’ in the accepted sense of them being fabricated. Neither are they ‘merely’ stories with a highly naturalistic gloss: both are based on the real experiences of real people. In the case of Pissed on the Job, the film’s basis is a series of confidential interviews with the real people. The events they have talked about are then reconstructed and their actions performed by actors. The film takes the form of a series of intercut ‘case studies’ with high-functioning alcoholics: we are introduced to each character in turn, seeing them first of all talking to an off-screen (and unheard) interviewer. Each character represents a ‘sector’ of society – there is a schoolteacher, a doctor, a nanny, a London Underground station manager, a housewife/mother – so that their ‘personal’ problem becomes indicative of a wider social issue. It is important that the people cast in these roles are unknown (or little-known) actors so that such a ‘social problem’ moment can be played out;2 if the people were played by clearly recognisable actors (or stars), then the effect would be diminished. In any case, it is difficult to say where, exactly, such a programme might ‘fit’ in terms of commonsense notions of ‘drama documentary’ and all the variations noted above. Clearly, the intention is to ‘document’ a specific social issue, and to do so by using the testimony of real people as the foundation for what is said. The ‘same’ issue could have been explored via a realist, fictional film – for example the Hollywood film When a Man Loves a Woman (Luis Mandoki, 1994, US) examines how alcoholism impacts upon a specific family’s life – but the problems and issues are explored – and, crucially, resolved – in very different ways in such narratives. Pissed on the Job is not simply ‘dramatised’ documentary (or ‘documentarised’ drama). One could argue, for the sake of simplicity, that it is in a ‘documentary style’, but I think this is too vague a category (after all, how many ‘styles’ of documentary are there?). The programme exists on a boundary between conventional nonfictional address and the range of other modalities that bubble to the surface when we consider what happens when one person speaks the words of another, or a set of filmmakers reconstitute and re-enact a particular slice of actuality.

In any case, despite their apparent ‘non-documentariness’ for some people, such films as Pissed on the Job or the Tina films are no more or no less problematic for a definition of documentary than were the films Grierson and his associates made some sixty years previously. As Brian Winston has argued, there is a considerable history to ‘reconstruction’ in documentary, and the techniques associated with reconstruction were widespread in the ‘Griersonian’ tradition of documentary filmmaking (1995: 120–3). The notion that ‘judicious’ or ‘sincere and justifiable’ reconstruction could (indeed, had to) take place in documentary was something that was broadly accepted. This was partly to do with the limitations of the time in that the simplest approach of filming with synch sound on location (what became the basis of the direct cinema approach) was at that point not possible. Intervention and fabrication of material that commonly existed in actuality was therefore often the only way (the filmmakers thought) of bringing certain things to the screen. Thus, what would in the contemporary moment be presented as a ‘video diary’ or ‘docu-soap’ – using location shooting and synch sound – was in Grierson’s day routinely ‘mocked up’ and reconstructed. Night Mail (Harry Watt and Basil Wright, 1936, UK), for example, famously reconstructed the sorting coach of the train. In a similar way, the story of A Job in a Million (Evelyn Cherry, 1937, UK) is told via a frankly stilted acted scenario, which is clearly meant to represent the ‘typical’ young man’s search for employment. In the twenty-first century, such material would be done cheaply and quickly, and on location. The question is: does this mean that such modern-day ‘versions’ of these films would be any more revelatory of the particular social phenomena that they set out to examine, simply because they are perceived as ‘more authentic’ to the modern viewer?3 The assumption might be that if the use of reconstruction becomes too obvious (either through filmmaker clumsiness or the changing viewing conditions for an older film) then the documentary loses some of its effectiveness.

Figure 3 Night Mail (1936)

Same story/different mode: the life, times and death of Aileen Wuornos

Although the examples given above are a mixture of re-enactment, dramatisation and interviews with real people (or, actors standing in for real people to retain their anonymity), we also need to consider the relationship between different modalities, different ways of telling the ‘same’ true story. In this respect, the Nick Broomfield documentaries Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1992, UK) and Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer (2003, UK) stand as an interesting comparison with the dramatised versions of the story seen in the films Overkill: The Aileen Wuornos Story (Peter Levin, 1992, US) and Monster (Patty Jenkins, 2003, US). For example, the end credits of Monster acknowledge the film’s ‘fictionality’ with the following caveat:

While this film is inspired by real events in the life of Aileen Wuornos, many characters are composites or inventions, and a number of the incidents depicted in this film are fictional. Other than Aileen Wuornos, any similarity to any person, living or dead, is not intended and purely coincidental.

Monster is, on one level, a fictionalised account of (part of) the Aileen Wuornos tale – as this credit makes clear. However, it is not at all clear that anyone knowing the basics of what happened in actuality could mistake the character of ‘Selby’ (played by Christina Ricci) for anyone other than the real-life Tyria Moore; even though there is some compositing of character traits, and some fictional events included, there is a residue of actuality that is unavoidable. Despite the dramatic form that the film takes, it still refers to an actuality. This is not to argue that Monster is a ‘documentary’ of course, but in a case such as this, where conflicting versions of the truth are the ‘subject matter’ as much as anything else, the different modes of telling this story cannot be easily disentangled. The ‘whole story’ of the Wuornos affair might never be totally told, but its telling lies somewhere in the ‘intertext’ of court records, documentary films, dramatised films, news broadcasts and so on, rather than any one definitive telling of the story. Jerry Kuehl states with some certainty that drama documentaries are completely unable to make any kind of truth claims. His argument appears to rest on a clear and definite split between modes: on the one hand there is ‘conventional documentary’, while on the other hand there are drama documentaries, which are incontrovertibly ‘fictional’, due to the fact that they use certain dramatic devices, scripting, actors and so forth. As Kuehl puts it, when referring to what he sees as problems with ‘simulated’ performances,

Episodes of which no filmed records exist are … inaccessible to dramatic artists. The language used by performers may be ‘authentic’ because derived from court records or other stenographic reports; but the inflections, accent, volume, and pace of what performers utter, as well as their gestures, expression and stance, will not be those of the persons they represent. It’s hard to see how the bricks of uniquely insightful portraits can be made from the straw of performances known to be inauthentic before they even begin. This inauthenticity is inescapable. (1988: 107)

As Steven N. Lipkin’s (2002) examination of based-on-a-true-story docudramas makes clear, however, the questions one needs to ask about these kinds of drama are very much to do with issues of truthfulness, and the viewer’s interpretation of what they see, to the extent that Kuehl’s dichotomy seems hopelessly simplistic. What makes the Wuornos story such an interesting area is that there are a number of different versions of the story, told from different perspectives, and comparing them draws out some of the differences between ‘documentary’ and ‘drama’ modalities. Lipkin’s work suggests that it is unwise to reject out of hand the possibility that films like Monster and Overkill can tell us something about the real events to which they dramatically refer. He argues that docudrama versions of events can function as a form of ‘persuasive practice’, using the legal term of ‘warranting’ to back up this claim. By warranting Lipkin means the strategies by which docudramatic forms draw together data into an argumentative framework, thereby making an assertion (or set of assertions) about ‘what really happened’ in a specific, actual scenario:

Works with a basis in prior, known events, actions and people refer to data already in the public record. They assert moral positions that ultimately become claims made by the film’s narrative and warrant these claims through formal strategies that bring together re-creation and actuality. (2002: xi)

Overkill falls into the category of lurid television movie adaptation of a ‘true life’ story – what Lipkin would categorise as a movie-of-the-week. It is also, unlike Monster or either of the Broomfield documentaries, focused a good deal on the police’s hunt for Wuornos. In this respect it is a police procedural, which is another staple of the true-life/true-crime types of films. The film begins with the incident where Wuornos (Jean Smart) and Tyria Moore (Park Overall) crash the car they are driving and, fleeing the scene, are spotted by a number of witnesses. It is when this incident is potentially linked to some other crimes that the hunt for the two women leads to the suspicion that Wuornos is responsible for a number of homicides in the area. The warranting process involves the invoking of the facts and figures of the police procedural to ‘anchor’ the assertions that the film makes, as well as referencing real people and locations, appealing to the audience on its ‘based on a true story’ foundation.

Due to their obvious documentary status, the Broomfield films do not have to make the same kind of appeals to their audience. There are, however, a range of conflicting ‘voices’ within the two films. The theatrical trailer for Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer is interesting for the way in which it almost completely effaces Broomfield as a presence or ‘voice’, in stark contrast to the rest of the film. It starts with a white on black caption saying ‘A new film by Nick Broomfield’. As we zoom slowly in on a photograph of Wuornos as a young girl, we hear (but do not see) Broomfield: ‘Aileen, let me ask you one question. Do you think if you hadn’t had to leave your home and sleep in the cars it would’ve worked out differently?’

Figure 4 Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer (2003)

The screen fades to black and then Wuornos appears in extreme close up. She talks about what she might have done, and what her life might have been like, if she had come from a ‘right on’ family background:

I would’ve become, more than likely, an outstanding citizen of America who would’ve either been an archaeologist, a paramedic, a police officer, a fire department gal, or an undercover worker for DEA, or ar- … did I say archaeology? … oh, or a missionary.

As she speaks, the camera holds her in close-up, achieving that ‘fly on the wall’, observational intimacy that we recognise from many documentaries and is often taken as the marker of authenticity par excellence. The brief scene with Wuornos then fades to black and another caption comes up that reads ‘Aileen Wuornos was executed for the murder of seven men on 9 October 2002’. This holds for five seconds, before adding ‘This is her story’.

It is interesting to note that the word ‘true’ is absent from that final sentence. Monster, the 2003 dramatised account of the Aileen Wuornos story, has the tag-line ‘based on a true story’. The different ethical and rhetorical registers we see in films that are ‘documentary’ and those that are ‘fictional’ (and there are a number of positions on a spectrum between these two) are blurred somewhat by films that are ‘fictionalised’ or ‘docudrama’ renditions of allegedly true events. Also, the ‘This is her story’ assertion from Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer’s trailer attempts to place the ‘ownership’ of the story firmly in Wuornos’s domain. Yet, as Broomfield’s films demonstrate – both in the people and events they show, as well as in their very existence – the story was not Wuornos’s to tell.

It is certainly ironic that the versions of the Wuornos story that can be termed ‘fictional’ depend to a large extent on their ‘this is a true story’ basis. This can of course be explained by the ways in which such tales are often told: they are marketed as a (more or less) truthful rendition of the events as they happened. An obvious difference between Overkill and Monster on the one hand and the Broomfield documentaries on the other is that the former two tell the story in an ‘unfolding’ fashion; which is to say, they tell the events as if we are there seeing them happen, from a specific vantage point, and they treat ‘what happened’ as the main events. The arrest and trial(s) of Wuornos, her subsequent incarceration and execution, not to mention the apparent changing (and some would say, losing) of her mind en route are almost completely ignored. This is actually an interesting issue, as it points to the ‘self-evident’ nature of events as they are presented to us in the fictionalised versions. They are, simply, ‘what happened’. Of course, the Broomfield documentaries can only ‘document’ what happens after her arrest (with any ‘back story’ being filled in via use of Broomfield’s voice on the soundtrack, with use of archive photographs and the like). It is in the nature of this kind of documentary that the ‘documentariness’ resides in how we as viewers are oriented to Broomfield’s search for (his own version of) the truth. This is conveyed to us via the apparently ‘artless’ Broomfield’s interaction with Wuornos herself and the people who orbit her world. Broomfield does not use reconstruction or re-enactment of events in order to convey ‘what happened’; in many respects, ironically, one could argue that his films show no real interest in ‘what happened’ but are rooted firmly in the present of the Wuornos case and where it might grotesquely lead next.

A key scene in Broomfield’s second film about Wuornos is interesting for the ways that two ‘discourses of sobriety’ – law and documentary – clash. It also raises important issues regarding the notion of reconstruction, and how it is often equated to fictionalising. In Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer, Broomfield himself is subpoenaed as a witness in the last of Wuornos’s appeal cases before her execution. He says at the start of this sequence:

I like to flatter myself that I was being asked for my legal opinion, but it turned out I was there to talk about Steve’s [Steve Glazer, Wuornos’s lawyer] marijuana smoking. The big question was whether Steve had consumed seven very strong joints before giving Aileen legal advice in prison.

He is then questioned on his techniques in the construction of the so-called ‘Seven Joint Ride’ sequence from Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer. The veracity of what we (think we) see on the screen (within Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer) is called into question by the prosecutor, who points to the different shirts that Steve is wearing in contiguous shots. Although Broomfield points out that ‘he probably changed his shirt … I don’t remember’ and offers access to the outtakes from that sequence, it strikes something of a body blow to his integrity as a documentarist. Certainly, we might as viewers be aware that reconstruction, ‘cutting and pasting’ and so on, do occur, but this is being held up as a clear case of something different: deliberately misleading manipulation. Having said this, this is the most important issue with regard to this sequence – the ways in which the two competing discourses are in a sense ‘battling’ for their version of ‘Wuornos’ to hold sway. Wuornos herself is always a highly-mediated presence in the Broomfield films, arguably as ‘mediated’ (which is to say, kept at some distance from us as viewers) as in either of the fictionalised accounts of her life. In many respects, both of the Broomfield films are about the wider issues of buying, selling, wrangling, as well as the betrayals felt and dealt by a highly contradictory woman. What comes across in these documentaries is that she and her crimes are a rich seam to be mined for meanings – either wider social meanings about the death penalty, or killers who happen to be women, and so on, or what she as a person might ‘mean’ by any of her statements (which become increasingly contradictory and problematic as the second film progresses).

Rights and wrongs

One of the key issues in relation to the Aileen Wuornos story is that she herself had no rights to it. The wrangling over who was going to tell the story is detailed in Broomfield’s first documentary, Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer. In this film there are several sequences where Aileen’s adoptive mother (Arlene Pralle, a born-again Christian barely older than Wuornos herself) and Wuornos’ lawyer, Steve Glazer, wheel and deal for payment for access rights to Wuornos. As Broomfield puts it, as he and Glazer drive up to Pralle’s ranch:

My main problem so far is that Steve and Arlene have told me that Lee [Wuornos] wants $25,000 for the interview. I had always thought that the Son of Sam law prevented people from profiting from their crimes, but apparently the Son of Sam isn’t in effect any more.

The next scene then involves Pralle coyly talking about Wuornos, with the occasional aside to Glazer, to check if she should have said something or not. Glazer talks of how ‘interesting’ and ‘fascinating’ the story and its characters are, with a view to convincing Broomfield that he should pay the $25,000. The camera pans up to Broomfield, looking sceptical. As he clarifies what the situation is regarding payment, he says (in voiceover): ‘In fact, Arlene and Lee’s relationship is extremely well-documented, and it seemed far cheaper at this stage to buy in some local TV footage.’ The ensuing news report includes footage of both Pralle and Glazer, both maintaining that the only motive for adopting Wuornos is Christian love. This is reiterated by the straight-to-camera comments of the local television news reporter, as she concludes her report.

It is not being argued here that Wuornos should have been able to profit from any films or books that allegedly tell the story of her life or what happened to her and her victims. (Indeed, the law in Florida prohibits this in any case). However, her supposed position as ‘America’s first female serial killer’ turned her into a potent commodity – something that was not overlooked by the adoptive mother and lawyer, nor the Marion County sheriff’s department, some of whose officers were alleged to have brokered film and book deals.

As Broomfield notes at one point in Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer:

All of the press attention had made her into something of a star … [there were] fifteen studios competing for her story … two feature films being negotiated … there were also the chat shows, documentaries, and the books…

The film then cuts to Wuornos, about to be given another death sentence, who rails against this behind-the-scenes dealing in her story:

The movie Overkill, that is a total fictional lie, that they framed me as a first-time … female serial killer – for the title for that movie … First female serial killer is not what I am … and my confessions prove it … yet they have taken the confessions and gone 200 per cent against what my confessions stated to get their bogus movie out.

Broomfield then speaks on the soundtrack, as Wuornos continues her statement:

Lee Wuornos insists she is not a serial killer as she did not stalk her victims or plan her crimes. As with the movie deals, Lee is also surrounded by a web of experts all competing with their own theories on her behaviour. Lee is portrayed as anything from a neglected and abused child who hates her father and is murdering him over and over again, to a sadist who takes pleasure in the agony of her victims.

The next scene sees Broomfield pursuing the sheriff of Marion County at the time, Don Moreland, with a view to questioning him about his and several of his deputies’ involvement in the alleged selling of movie rights to the Wuornos story. Moreland runs into a building and locks the door. It is difficult to discern where the truth of the matter lies when so many of the people involved are clearly driven by such mercenary, self-serving motives. However, what this does mean is that the secondary discourses around the Wuornos case – the serialisations, the movie adaptations, the Broomfield documentaries – all must be viewed as part of the ‘whole picture’. As discussed above, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer references Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer, when the prosecutor at one of the appeals calls into question Broomfield’s documentary methods in that first film. Wuornos herself refers to other mediations of her story, and seems well aware of (at least some of) the implications and worth of her tale. The whole web of film and media references (and here we must include the news broadcasts of the hunt for Wuornos and the subsequent media circus that ensued during her various trials) effectively constitute a bizarre and damning ‘supra-documentary’, where truth would perhaps be stranger than fiction, if only we could discern where exactly one ended and the other began.