The focus of this chapter is the relationship between documentary and animation. There is a long tradition of animation being used as a mode of expression within documentary – for example to demonstrate the complicated workings of machinery in an otherwise live-action documentary about industry. We could more accurately refer to these sorts of films as documentaries with animated sequences. However, the point here is not merely to outline how documentaries might use animation, but to investigate some of the interesting problems that arise when examining where these two apparently discrete modes meet in a more direct manner. In other words, we shall explore actual ‘animated documentaries’. In chapter four we looked at documentary and comedy as modes, and the intention is to do the same thing here in relation to animation and documentary. The contention is that there is a tendency to view documentary as a mode of discourse that will not allow such subjective, expressive aspects as we associate with comedy and animation. This tendency is strongly rooted in the philosophical basis of certain forms of representation – and therefore means we must think through some complex debates about realism and representations of the real – but here it will be argued that it is erroneous and unhelpful if we wish to fully understand how documentary and animation (and comedy, for that matter) actually work. As we have seen in earlier chapters, ‘documentary’ must now be seen as a range of strategies in a variety of media; we can no longer cling to essentialist notions of what the term might mean. As previous chapters have outlined, there is a useful distinction to be drawn between the categories ‘nonfiction’ and ‘documentary’, and the purpose in this chapter is to examine the ways in which this distinction is inflected by another interesting category of moving image production – animation. The notion that a documentary can only deal in an apparently straightforwardly ‘realist’ set of representations has therefore come under challenge in recent times, and engaging with animated documentary demonstrates clearly how documentary can be the realm of subjectivity, fantasy, and non-normative approaches to understanding the world around us.

Animation has long been used in informational and educational films that can clearly be included as part of the documentary category. During the First World War, there were the Kineto War Map (F. Percy Smith, 1914–16, UK) series of films that used animated map sequences to show the progress of the war. Indeed, there was a strong association in this period between animated films and propaganda (see Ward 2003; 2005a). A later use of animated documentary in a propaganda context was Disney’s Victory Through Air Power (Clyde Geronimi, Jack Kinney, James Alger and H. C. Potter, 1943, US), a combination of animation and live action. Animation was also used in the documentary context by Len Lye, a New Zealand-born innovator who worked under John Grierson at the Empire Marketing Board and GPO Film Unit. Lye’s films used techniques such as ‘direct animation’ (scratching or painting directly onto the film strip) and their often abstract patterns and shifting rhythms are a clear link to a more modernist, experimental tradition of filmmaking. At the same time, a film such as Trade Tattoo (1937, UK) can clearly be read as a documentary: in the film, Lye uses found footage from other GPO documentary films showing aspects of trade and industry. These were then ‘creatively interpreted’ via colour optical printing and other techniques; Lye also added some abstract patterns and playful captions over some of the original footage, as well as an up-tempo soundtrack. The result is a kinetic paean to the hustle and bustle of trade, where the animation techniques used literally seem to ‘bring to life’ this apparently everyday activity.

As well as such animated films (which are often discussed within the category of experimental or avant-garde film, rather than documentary; see O’Pray 2003: 44–7), the other main area where animation has addressed social issues in a way that compels us to consider the relationship with documentary is in what might broadly be termed the ‘independent’ sector, especially that populated by women practitioners. There is a long association between animation and female expression (see Pilling 1992), and the work of Candy Guard, Joanna Quinn, Caroline Leaf, Ruth Lingford and others – while not necessarily ‘documentary’ animation – certainly uses animation and its specific mode of representation to address real social issues. One body of work that does successfully combine documentary and animation in order to make a political statement about the world is the work of the Leeds Animation Workshop. The Workshop was formed on an informal basis in 1976 in Leeds, England, when some women came together to address the lack of workplace childcare facilities in their area by making an animated film, the campaigning Who Needs Nurseries? We Do! (1976, UK). The group subsequently continued to use animation as a way to address social issues, making films that offered a polemical, feminist-oriented perspective on representation (for example, Give Us a Smile (1983, UK)). The work of the Leeds Animation Workshop therefore is a good example of a specific mode of practice – that of the community-based, ‘activist’ producers. As Irene Kotlarz points out, the films were ‘intended to provoke discussion rather than simply to entertain’ (1990: 240). The fact that the workshop more often than not produced animated documentaries points to the perception of animation as a mode that can draw together complex social issues and simplify matters (sometimes to ironic effect) to present an argument about the real social world. Who Needs Nurseries? We Do! for instance, speaks from the children’s point of view – a strategy that intensifies this feeling of the problems actually being simple and straightforward (and in urgent need of a solution).

Typologies and categorisations

As we saw in chapter one, the way in which we categorise documentaries is very important. Maureen Furniss (1998) has suggested that all moving image productions should be conceptualised as existing on a continuum characterised by the poles ‘mimesis’ and ‘abstraction’ and this certainly allows one to think about the relative weight given to different modes of representation within any particular motion picture. Animation – and animated documentary in particular – ‘suffers’ from the predisposition to equate notions of realism with an indexical correspondence to a pro-filmic actuality. In other words, for something to ‘be realistic’ it is commonly supposed that it must directly resemble the thing that it represents. In the case of documentary especially, we tend to find that this translates into the idea that documentary as a category not only has to look and sound a certain way, but that any form of ‘subjectivity’ or ‘personal expression’ is out of place. As we have seen in earlier chapters, though, there is a long tradition of ‘creativity’ (or ‘creative treatment’ to use a Griersonian phrasing) in documentary production. Animation represents one of the clearest challenges to simplistic models of what documentary is and can be, quite simply because you cannot have an animated film that is anything less than completely ‘created’. The frame-by-frame production process means that animation is the most ‘interventionist’ of modes; and, some would argue, this level of intervention (allied with, as we shall see, often startling levels of ‘expressivity’ and experimentation) means that it cannot adequately represent the real – which should be one of the defining features of documentary. Yet, as we shall see, animation is a mode perfectly suited to documentary production.

Paul Wells has offered a useful typology of animated documentary modes. He refers to the ‘documentary tendency’ of some forms of animation and sketches four modes – the imitative, the subjective, the fantastic and the postmodern. The ‘imitative’ mode is that type of animated film that offers an imitation (or pastiche) of live-action documentary tropes. Key examples here are some of Disney’s instructional shorts (for example, the You and Your… series (1955–57, US)) or Winsor McCay’s The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918, US), which at times startlingly resembles a live-action newsreel. All of these animations in some way borrow recognisably documentary conventions. As Wells points out:

The closer that animated films conform to ‘naturalist’ representation and use the generic conventions of some documentary forms (for example, the use of ‘voiceover’; the rhetoric of ‘experts’; the use of ‘factual’ information etc), the more it may be said to demonstrate documentary tendencies. (1997: 41)

A good recent example of this kind of documentary is What’s Blood Got To Do With It? (Andy Glynne, 2004, UK), one of a series of short animated documentaries.1 The film is a parody of the public information film tradition, using expository techniques to put across a highly compressed history of blood and blood donation. In this respect it can be seen as a ‘consciousness-raising’ film, asking people to not only understand the issues, but to also take some positive action and give blood. The voiceover (by comedian Alexei Sayle) and the images are deliberately comical, playing on the cartoonal style of certain types of animation. (Compare this to another film in the series, Leona. Alone (Rani Khanna, 2004, UK) about a girl who suffers from sickle-cell disease, where the animation style is less frenetic and the film uses the girl’s own voiceover as the soundtrack – this is more akin to what Wells calls the ‘subjective’ mode (see below)). Indeed, many of the jokes appear to draw attention to the ‘condensation’ that is occurring: in order to fit this much information into the three-minute running time, the pace and connections between different aspects of the information require that a lot is condensed, leading to some amusing juxtapositions. For instance, the condensation of large eras of history – and their differing views of what blood is, what it does, and so forth – is very amusingly achieved via some spoof magazine covers, where the images and captions speak volumes about how scientific progress rapidly changed how blood was viewed. Although there is a fairly typical (animated) use of caricature and comical condensation, therefore, we should also note that this is in the service of an expository documentary impulse – in other words, the straightforward presentation of ‘self-evident’ facts and information about the subject matter. While there seems to be some licence taken with how the animation is presenting the material, it is actually the case that this film follows many of the conventions of standard expository documentaries.

The subjective mode is one that accentuates what some would say is the inherent ‘subjectivity’ of animation: much animation emphasises the specific interventions of the animator – their ‘worldview’ for want of a better term – and animated documentaries that fall into this category play upon this by linking the creative acts of the animator with apparent access to the subjective thoughts of their main characters (real people). Subjective documentary often ‘moves beyond its basis as the expression of an individual voice and finds correspondence in viewers to the extent that it articulates social criticism’ (1997: 43). The animatedness of such documentaries is something that draws out some of the problematic issues of a belief in an ‘objective’ position from which certain stories can be told.2 Below are some notable examples that arguably come into this category.

The fantastic mode of animated documentaries in this typology is one that explores what lies beneath the surface of ‘everyday’ reality, often with a surrealist approach as typified by someone like Jan Svankmajer. As Svankmajer contends, he looks to make ‘fantastic documentaries’ using what he terms ‘militant surrealism’. The suggestion is that ‘objective reality is an illusory, unhelpful and ultimately misleading concept’ (1997: 44). As Wells points out, although this mode can be seen as an extension of the subjective mode, it can tend towards the abstract and surreal, so that rather than the films transmitting a self-evident ‘look’ into a specific person’s subjective view of their situation (as is the case with, say, Leona. Alone), what is achieved is often oblique, mysterious and contradictory. Of course, it is entirely possible for a ‘subjective’ film to exhibit these characteristics – especially so if the subject in question has some ‘problem’ with communicating their own subjectivity (see below for the discussion of A is for Autism (Tim Webb, 1992, UK)) – which is why Wells makes the point about these categories overlapping to some extent. However, it is certainly the case that one of the most widespread and compelling forms of animated documentary, especially in recent years, has been the ‘creative interpretation’, via animated visuals, of a real person’s testimony or reminiscence.

If the ‘fantastic’ mode offers a glimpse beneath the surface of the everyday, and raises doubts about documentary’s ability to adequately represent the fullness of existence, then Wells’ final mode, the ‘postmodern’, goes one step further and implies that documentary itself is a mode with no special claim to ‘truth’ or ‘reality’, but is rather ‘merely "an image" and not an authentic representation’ (1997: 45). On the face of it, the ‘relativist’ dimension of postmodernism seems ideally suited to animation as a form: it could be argued that any animated documentary, freed as it is from the indexicality of the live-action/photographed image, allows the animator’s ‘subjectivity’ to automatically question some of the certainties of the ‘objective’ discourse of documentary as a form. However, while it is important to recognise the inherently constructed nature of animated documentaries, this does not mean that we can make the leap to state that any and all truth claims or observations made by animated documentaries can be dismissed as ‘relative’ or ‘merely’ a product of the animator’s point of view or subjectivity. The formal and aesthetic aspects of animation tend to mean that the creativity and subjectivity of the creator are considerably more foregrounded than is often the case with live-action work; nevertheless, the claims made about the real world of actuality by animated documentaries must be evaluated according to what they say about that real world, and not on the basis of such formal or aesthetic criteria.

As was made clear in chapter one, constructing typologies, or thinking about how and where specific examples might fit on a continuum, are very useful things to do, as they emphasise the relative relationships between modes. Therefore, one must recognise that there are no definite answers here. Indeed, it can be suggested (and Wells would surely not disagree) that there is considerable overlap between the four modes outlined above and, certainly, there are some animated documentaries that arguably use more than one mode. With documentary, we are dealing with what Carl Plantinga refers to as an ‘open concept’ (see chapter one). It is no coincidence that one of the most interesting books in the area of documentary studies is entitled Blurred Boundaries, and that it openly engages with the ways that fiction and nonfiction inter-relate and overlap. (Though interestingly, Bill Nichols makes no mention of animation as a form.) The notion of ‘prototypicality’ (something that Plantinga borrows from George Lakoff) is of central importance here (and to arguments advanced in other chapters in this book – see chapters one and two in particular). What this suggests is that we might well strive to define and pin down what something ‘is’, but actual examples will tend not to ‘tick all the boxes’ of a particular definition. So it is with both animation and documentary: there are some examples that appear to fall right in the middle of these categories; they fulfil all the ostensible criteria. There are other examples that appear to be on the periphery, to ‘not quite fit’. In many respects, my main argument throughout this book is that thinking about such examples and how they relate to others is one of the best ways of understanding the entire field. It is certainly the case that, as Gunnar Strom states, ‘the term "animated documentary" may seem like a contradiction’ (2003: 47), but the more we examine the interface between these two apparently opposed poles, the more useful their interaction becomes for understanding how both modes operate.

Representing the real in an unreal way: the contradictory nature of animated documentary

Although there are clearly a range of styles and techniques used in both animation and documentary, it has to be said that there is something inherently ‘reflexive’ about animation, especially in relation to documentary. In Wells’ typology of modes, even the imitative mode holds a strange position in the sense that even the most ‘realistic’ of animation (for example, something from the ‘hyper-realist’ style of Disney) will be watched as animation, rather than as a ‘recording’ of an actual pro-filmic world. That is, despite any truth claims made, or real-world situations and relationships shown, the ‘animatedness’ will still be an overriding feature of the film for the viewer as they watch the film. This is not to say that the claims made or situations represented are thereby somehow completely invalidated – on the contrary, it might well be the case that an animated documentary manages to reveal more of the ‘reality’ of a situation than any number of live-action documentaries. But the ontological status of the images (the sounds are arguably of a different order, and this issue is returned to below) means that the perceptions of ‘animatedness’ and ‘documentariness’ are in conflict to a large degree. This is not necessarily a problem: such conflict is arguably a requirement for any form of expression that wants to engage with the real world in all its complexity and contradiction.

In an essay about documentary and animation, Sybil Del Gaudio examines what she calls the ‘reflexive’ mode (one that differs slightly from that proposed by Nichols in relation to live-action documentary), focusing in particular on some documentaries that ‘use animation to deal with scientific theory’; she argues that ‘such films serve as a means by which a filmmaker can question the adequacy of representation in relationship to that which it represents’ (1997: 197). In other words, the very constructedness of the animation forces the ‘reflection’ on form and meaning that is central to a ‘reflexive’ mode, something that sometimes gets lost in the seductively mimetic world of live action. This is another role that animation fulfils (along with the straightforward ‘simplification’ of complex processes that we might see in training and educational films that use animation – see Crafton 1993: 158): drawing attention to the specific signifying practices of certain documentaries.

One common feature of a significant number of animated documentaries is their tendency to use animation techniques to explicitly represent and interpret the thoughts and feelings of their subjects. There are two main reasons for this ‘subjective’ tendency. First of all, in this context we are often talking about highly abstract feelings, or taboos, or are dealing with people who find it difficult to articulate. Secondly, there are some issues relating to anonymity – animation offers a ‘cloak’ that live action might not: as we are dealing with direct testimony we are effectively seeing these people’s thoughts and feelings visualised. There are of course other conventions for representing someone who might wish to remain anonymous – the chief example being the ‘silhouette’ style testimony – but such approaches do not offer the creative freedom that animation affords.

For example, in the short series of animated documentaries, Animated Minds (directed by Andy Glynne, 2003, UK) we hear the spoken testimony of real sufferers from various mental illnesses, accompanied by animated visuals. The individual films are Fish on a Hook (panic attacks and agoraphobia), Dimensions (schizophrenia), Obsessively Compulsive (obsessive compulsive disorder), and That Light Bulb Thing (manic depression); each film has a very different style. In Dimensions, for example, we hear the voice of a man who tells us of his experiences of suffering from psychotic interludes. The animation techniques used here tend towards a fragmentary, ‘overlaid’ look, where elements of a recognisably external reality (newspaper headlines, London Underground tunnels) are fused and altered to reflect the mentality of the speaker. At the onset of the disorder, the voiceover tells us:

Initially the experiences were quite positive; I was living outside consensus reality … [with a] very heightened sense of awareness … delusions of grandeur, which are quite pleasant.

It then cuts to a newspaper, and he says ‘so, I’d open up a newspaper and I’d think it would all refer to me’. The headline ‘Okri for Booker Prize’ then dissolves/morphs to read ‘Young genius writes debut novel’. Similarly, people on the radio were imagined to be speaking to him directly. During both of these sequences, the animated backgrounds are fragmentary and shifting (trees, power pylons, the aforementioned headlines), but the colours and motion do not really imply threat. As the speaker says, it was all ‘quite pleasant’.

As the affliction became more oppressive, we hear that he started to hear voices – often recognisably those of his sister, father, mother – encouraging him to self-harm. As things get more and more disturbing, the animation consists of eerily shifting human silhouettes and subliminal messages that flash up too quickly for the eye to register, saying ‘WHY DON’T YOU SLIT YOURSELF? … ‘YEAH … IT’S EASY … GO ON.’ The shift to an alternate reality is almost complete: ‘I do find it amazing, the power of the human brain, that it can recreate … ten, twenty voices perfectly’, so much so that he ‘could never imagine the old, normal reality coming back’.

Obviously, one could make a live-action documentary about this affliction and include testimony of the person involved. But it is the use of animation that is interesting, as it can perfectly trace the contours of such a shifting and rapidly condensed thought process in a way that is out of reach for live action. Animation is the perfect way in which to communicate that there is more to our collective experience of things than meets the eye. As suggested elsewhere regarding rotoscoped films, the recent work of Bob Sabiston in particular (Ward 2004; 2005b; forthcoming), it can be argued that animated films offer us an intensified route into understanding the real social world, by virtue of the peculiar dialectic that is set up between knowing that this is a film about a real person (and we can hear their actual voice) and knowing that what we are looking at is an animated construction, with nothing of the indexical correspondence that we have become so accustomed to. The animation techniques used are a clear example of the ‘creative treatment of actuality’ – such that John Grierson would no doubt find animated documentaries something of a logical conclusion to his famous definition.

In Obsessively Compulsive, the interviewee talks about his struggles to come to terms with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). The main symptom in this person’s case is an inability to carry out even the simplest of day-to-day tasks (walking across a room, drinking a cup of tea) without an ‘intrusive thought’ breaking in and preventing the completion of the task. In this particular person’s case, his intrusive thoughts were concerned with Saddam Hussain: whenever he thought about Saddam, he worried that his thinking about him was causing the Gulf War to escalate. This then led to him obsessing over his inability not to think about Saddam. The animation techniques used draw a clear connection between the ‘real world’ people and events and the ways in which they can quickly become part of a deluded fantasy world. It is this ‘subjectivising’ of elements of actuality that some might find problematic – but it is equally clear that the film is documenting the mental processes inherent in such a disorder. The use of stop-motion, ‘looped’ animation of an actor, while we hear the real voice of the OCD-sufferer, emphasises the repetitive, cyclical nature of OCD. The final image of the film perfectly captures this motif: the camera tracks back to reveal a cross-section of a ‘compartmentalised’ head, with each compartment containing an animated version of the man obsessively performing an action.

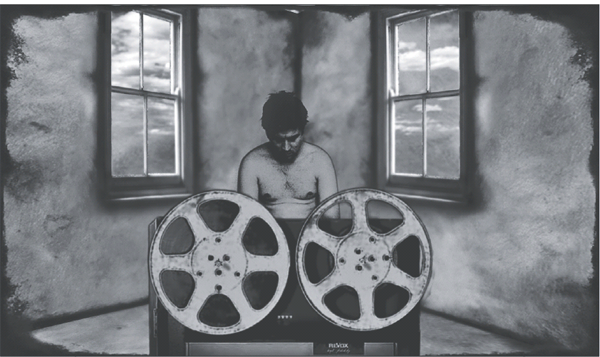

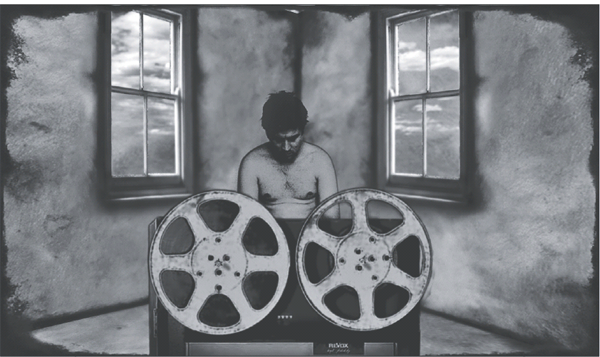

Figure 7 Obsessively Compulsive (2003)

A different technique is used in the mainly live-action film Feeling Space (Iain Piercy, 1999, UK), but the objective is similar: to try and visualise what a sensation (or lack of it) is like. This film uses animated sequences at certain points to represent the thoughts and feelings of two men, Brian Baistow and Tommy Cannon, who were born blind, describing their journeys through Glasgow. At one point they talk about how ‘road signs’ for blind people might helpfully consist of a street-side sculpture at ground level that they can feel the texture of in order to ascertain where they are, what buildings are around them, and so on. As they speak of the cityscape, however, shots of buildings are ‘cloaked’ by animated blank sheets, until they are featureless blocks. This works as a strong visual metaphor for something most of us take for granted – the ability to see, the wonder of architecture that surrounds us – but what makes this work as a documentary is the linking to the specific experiences of the two speakers. The two men describe in some detail the textures, sounds and smells of Glasgow, and how they feel at various points. The animation functions as a way to visualise (ironically enough) something that would otherwise remain at the purely verbal level. But it is in the rendering of the realities of these two people’s day-to-day lives that the film develops as a documentary. In common with the other films discussed in this chapter, we are given insight into something we would otherwise not know anything about, let alone understand. The animation used exists as a contrast, something that draws out and emphasises the shortcomings of conventional live-action representations of what the world is like. The long-standing assumption about documentaries is that they reveal to us what something ‘is like’ by showing, or by observing. The indexical link between the pro-filmic actuality and the imagery that appears in the documentary is a very strong one; however, in the case of Feeling Space, we (the viewers) are seeing what the subjects of the film cannot see, and they are experiencing their milieu in a way that we cannot, by virtue of actually being able to see it. It is this paradox that is creatively addressed by the animated sequences in the film: an attempt to document the undocumentable.

The animation tendencies seen in all of these examples come under what Paul Wells has termed ‘penetrative animation’, following John Halas and Joy Batchelor’s use of the term. Here, penetration refers to animation’s

ability to evoke the internal space and portray the invisible. Abstract concepts and previously unimaginable states can be visualised through animation in ways that are difficult to achieve or which remain unpersuasive in the live-action context. (1998: 122)

Thus, the states of mind documented in the Animated Minds films, Feeling Space, or Tim Webb’s landmark film A is for Autism become easier to understand as a consequence of their animatedness. Webb’s film uses the drawings of actual autistic people, animating them while the various people reflect on their autism on the soundtrack. The fact that autism is not one ‘thing’ but rather is a spectrum of disorders (from mild to severe) makes the subjectivised, ‘individual’ strands of different animation techniques (as well as live-action montage) a highly appropriate mode for representing it. The film works as a documentary precisely because of its ‘hybrid’ aesthetic. In attempting to represent to the viewer a hidden or masked reality – what is it like, subjectively, for your subjectivity to play ‘tricks’ on you? – A is for Autism draws out some of the problems and contradictions of trying to represent the ‘real world’ in the first place. One of the characteristics of autism is a tendency to take things that are said very literally, and for ‘commonsense’ ways of looking at the world to be far from sensible. People with autism are often thought to be intellectually deficient or unable to communicate ‘properly’, but more often than not, their apparent deficiency is merely them looking at the world in a way that is very different from ‘the norm’. In the film, one person reflects on the soundtrack that if someone points something out to them that they find interesting, they might not be able to ‘see’ it, even if it is obviously ‘there’, and that they might seem to be ‘distracted’ by irrelevant things. As they put it: ‘I always have trouble "finding" it … [but] I can see something boring straight away.’ Such a statement raises all sorts of issues for visual representation, yet Webb manages to brilliantly convey this problem by using one of the speaker’s own drawings, inverting it, and animating it. Within the drawing, a car repetitively moves backwards and forwards next to a tree, but does so at the top of the frame, upside down, rather than at the bottom of the frame. In another part of the drawing, some figures walk round what looks like a rocket (though it may be a church). There are also some random squiggly lines, moving about in yet another part of the picture. As we hear the speaker, the image inverts so that the car is the ‘right way up’, and the camera zooms in on it. Doing this means that things that were previously the right way up are now ‘wrong’, however. As the speaker talks of being able to ‘see something boring straight away’, the camera zooms into the mess of the squiggly lines. This underlines the visual ‘confusion’ that the speaker refers to, and is an effective way of communicating this to the viewer.

It is no coincidence that A is for Autism uses as a basis the drawings of actual sufferers from autism. This, then, is another common feature of animated documentaries that is worth stressing: the tendency towards collaborative working methods or, at the very least, methods that draw in the subjects in a way that is rarely seen or felt to the same extent in the live-action documentary context. A is for Autism is called ‘a collaboration’ in its opening credits. Bob Sabiston’s short film Snack and Drink (1999, US), which uses his computer rotoscoping technique ‘Rotoshop’ to visualise the mindset of Ryan Power, an autistic teenager featured in the film, includes some sequences that were animated by Power’s mother and aunt.3 It is this hands-on involvement of the subjects of these films in the actual production process that makes animated documentaries potentially very interesting. Indeed, an early version of Bill Nichols’ typology of documentary modes (discussed in chapter one) includes the ‘interactive’ documentary and a significant number of animated documentaries can be said to be ‘interactive’ in this sense. As noted in chapter one, Nichols describes the interactive documentary as a category where ‘images of testimony or verbal exchange’ feature heavily, and there is an emphasis on ‘various forms of monologue and dialogue’ (1991: 44). In other words, unlike, say, the expository mode (with its use of ‘voice of God’ exposition) or the observational mode (with its use of ‘fly-on-the-wall’ techniques) the interactive documentary tends to rely on the filmmaker’s interaction with their subjects, most often embodied in the form of an interview. Thus, the testimony or forms of monologue/dialogue become the main focus for ‘interactive’ documentaries (see Ward, forthcoming). Furthermore, as noted above, many of the animated documentaries discussed here are also interactive in the sense that the subjects themselves will often interact with the animator by becoming involved in the production process. This is, of course, a vital point to make when we consider that the topics of these films are precisely the supposedly incommunicable thoughts and concepts about what it is like to be blind, autistic and so on. These films could not really exist without the express involvement of the people they ‘are about’. Clearly this can be said of any documentary, but it is never truer than with these films, and it is in their ‘interactive’ and ‘penetrative’ representing of a worldview that they push back the boundaries of documentary signification.

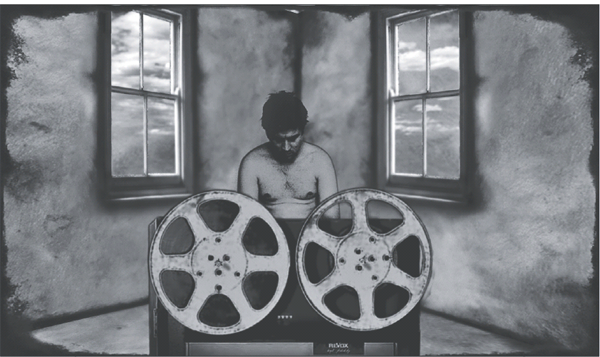

Figure 8 Snack & Drink (1999)

A related term to the ‘penetrative’ as outlined above is the ‘optical unconscious’. This term is borrowed from Walter Benjamin (1979) and it is very useful for understanding how we might ‘see’ and understand things that are not immediately apprehendable simply by looking. There is a difference in the sense that the ‘optical unconscious’ was Benjamin’s way of theorising how certain techniques – for example, magnification, inversion – might ‘make strange’ the familiar things that surround us and make people see the world in a new and different way. This is different to ‘penetration’ in the sense that the latter is focusing on how certain techniques – animation, in particular – might penetrate beneath the surface of something (for example, a social process such as banking) and reveal ‘how it works’. But the two concepts are closely related. The ‘optical unconscious’ is a useful term for understanding how certain animation renders the dream state to spectators (Ward 2005b), yet what is of interests here is how animation techniques (and it should of course be remembered that there are many kinds of animation technique) in some sense get beneath the apparent certainties of mere appearance. Such a move should again remind us of Grierson’s exhortation to ‘creatively treat’ actuality rather than merely ‘reproduce’ it.

Of course, the notion of attempting to foreground an ‘optical unconscious’ can be seen as merely one strategy amongst many others that might be termed ‘modernist’ in the political, revelatory sense of that term. The point of such an ‘unconscious’ is to delineate and understand how the world ‘really works’, rather than merely accepting it and taking it at face value. Bearing this in mind, we can see how the use of animation techniques to represent aspects of the real world offers a route into dissecting the taken-for-granted assumptions that underpin our understanding of that world. For example, Emily James uses a collage of found footage, animation, puppets and other stop-motion techniques in order to construct a critique of unfair globalised trading in The Luckiest Nut in the World (2002, UK). As Mike Wayne points out, this film ‘illuminate[s] the yawning contradiction between what the discourse of neo-liberalism imposes on Third World countries as a route out of poverty and the actual outcomes, which turn out to be more poverty’ (2003: 230–1). Likewise, Karen Watson’s animated film about child abuse, Daddy’s Little Bit of Dresden China (1988, UK) uses a range of animation techniques, along with a combination of ‘real’ and ‘acted’ voices in order to explore the hypocrisy and contradictions inherent in certain ‘commonsense’ assumptions about this social taboo. The apparent sanctity of the family unit – along with the ‘Othering’ of abusers (the myth that they are always strangers rather than family members) – means that in commonsense discourse, it becomes impossible to talk about the issue in any meaningful way. In the same way that the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund are the engineers of the very problems they say they are trying to solve, so it is with the problems in Daddy’s Little Bit of Dresden China, where the apparent safety of family life is revealed to be a sham. It is impossible to offer a critique of these two social problems without recognising the contradiction that lies at their heart, and the use of animation does much to address this contradiction. As Wayne states in relation to The Luckiest Nut in the World:

The immanent critique of a concept like ‘trade liberalisation’ is also then a critique and reworking of the generic materials of mass culture whose ‘innocence’ and naivety are juxtaposed (with comic and tragic effect) with brutal realities. (2003: 231)

In other words, it is in the very form that the material takes that we can discern critique. Daddy’s Little Bit of Dresden China for example, makes great (ironic) play of invoking fairytales, as well as other ‘mass’ or ‘folk’ forms (for example, the tabloid press and the ‘commonsense’ beliefs it tends to peddle) in order to draw out the ways in which these forms are often complicit in the continuation of a social problem. The bravura sequence in the pub, where voices on the soundtrack jostle with one another to condemn paedophiles while the animation literally tears away layers, and the men ‘eye up’ the barmaid, shows brilliantly the hypocrisy that underpins much commonsense or populist discourse on the matter.

The complexity of the sound-image relations in Daddy’s Little Bit of Dresden China is in fact a common feature of many animated documentaries. There is ‘realism’ or indexicality to the sound that does not reside in the image, and it is this more than anything else that helps to make animated documentaries of considerable critical importance. A large number of films in the animated documentary category consist of voice tracks that are recordings of real conversations, interviews, or pseudo-monologues which are then ‘creatively interpreted’ by the animated imagery. For example, the ‘confessional’ we hear in Aardman’s Going Equipped (Peter Lord, 1989, UK) consists of a young man talking about his experiences as a burglar. While we hear the real man talking on the soundtrack, we see a combination of stylised live-action footage (showing things like the squalor of his home life) and a claymation figure in a room who ‘speaks’ the words we hear. This is an example of what Michael Renov (2004) has referred to as ‘acoustic indexicality’ in relation to the soundtracks of animated documentaries. His discussion of Australian animator Dennis Tupicoff’s film His Mother’s Voice (1997, Aus.) stresses the ways in which the animated visuals ‘creatively interpret’ an ‘authentic’ soundtrack. Kathy Easdale’s son Matthew was shot dead in Brisbane in 1995 and the film’s soundtrack consists of a recording of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s radio interview with her, talking about how she felt when she heard about her son’s death. Tupicoff draws attention to the fact that a real soundtrack can be interpreted in very different ways by playing the interview twice but changing the visuals – the first time we see a rotoscoped re-enactment of some of the events from the evening of the shooting, the second time we hear the interview we start in a room with Kathy Easdale and the interviewer, but the camera soon departs to roam around outside the house while she continues to emotionally remember the events. As Emru Townsend points out:

Tupicoff … says, ‘By presenting just two of the many possible points of view that might accompany the voice of Mrs Kathy Easdale, I hope the film leaves the audience to imagine others, and to ponder its own response to her pain.’ The film itself tells the audience that what we see is not an absolute; the same events, narrated by the same person, can be observed, interpreted and experienced in many different ways. (1998: n.p.)

This goes right to the heart of why animated documentaries are vitally important: because they often use this trope of a ‘real’ soundtrack – inter-view, snatches of dialogue and so on – that is then creatively interpreted by the animated visuals. As the viewer can be under no illusion that what they are looking at is, categorically, a construction, then this prompts them to consider the nature of that construction, and its relation to the sounds we are hearing. This is something that is often taken for granted in relation to live-action documentaries, with the apparent ‘naturalness’ of the link between image and sound. The question that is implicitly asked here is: if someone is speaking about something, should we be watching them; or perhaps we should be watching a re-enacted version of what they are talking about; or watching an animated version of what they are talking about; or, perhaps we should simply leave the room and wander around outside, taking in the view? The assumption that documentary visuals should merely ‘illustrate’ the sound (or conversely, that documentary sound should act as nothing more than a ‘back up’ to the images) is critically foregrounded by animated documentaries in general. Indeed, as this chapter has suggested, animated documentaries should receive more scholarly attention, as they potentially provide answers to some of the more troubling questions asked of documentary as a field.