A Family Tragedy

When the Medina County Sheriffs Department initiated a nationwide search for seventeen-year-old Teresa Bickerstaff, many of her neighbors didn’t expect her to be found alive.

Despite an All Points Bulletin issued to police agencies throughout Ohio to be on the lookout for the petite teenager, it seemed to be a good bet that if she was found, it would be under a pile of leaves or in a shallow grave. It appeared she had been kidnapped.

The search for the missing teen began after an early morning fire raced through the two-story property of the Fred Bickerstaff family on August 28, 1980, in rural Harrisville Township. A neighbor who telephoned the alarm reported that she heard a loud explosion about seven A.M., and when she peered out her window, saw a heavy cloud of smoke billowing from an upstairs bedroom of the house. By the time firemen from the crossroads community of Lodi arrived at the neatly kept wood-frame house on Kenner Road, quickly followed by a crowd of neighbors and curiosity seekers, it was already too late. The house was enveloped in flames.

Thirty-eight-year-old Donna K. Bickerstaff and her sons, fourteen-year-old Fred J. Bickerstaff, Jr., and thirteen-year-old Kenneth Bickerstaff were already dead. Their pitifully charred bodies were found inside the fire-gutted,

year-old ranch-style house by firemen poking through the burned-out shell. The bodies of the boys were in upstairs bedrooms. Their mother’s horribly charred corpse had plunged onto the first floor when the upstairs collapsed.

A maze of firetrucks from Lodi and from the Lafayette Township Fire Department, squad cars from the Medina County Sheriffs Department, rescue vehicles and ambulances, and a huge crowd of people were still gathered at the smoldering house at about nine-thirty A.M. when Fred Bickerstaff, Sr., returned home from his job at the Alcoa Aluminum Company plant in Cleveland, some forty miles north. Sheriffs officers informed the distraught family man that his wife and sons were dead.

A muscular man with thick black hair and a heavy, drooping mustache, Bickerstaff told Medina County sheriff John Ribar that he had left for his midnight shift at the foundry at about nine-thirty the previous night. The thirty-seven-year-old man said his wife and sons, and his daughter Teresa, were in the house when he left. He explained that the girl had recently returned home from California, where she was staying with an uncle.

A frantic search by firemen and sheriffs deputies through the still-smoldering debris inside the burned-out building failed to turn up any trace of the girl. Deputies who fanned out through the neighborhood to question residents of nearby houses had no better luck locating her.

The neighbor who reported the fire told investigators she had heard four or five popping noises coming from the Bickerstaff house at about two A.M., and when she peered out the window she noticed that lights were on all over the house. Another neighbor who lived about a half mile away said she telephoned the Sheriffs Department at about five A.M. and told them she smelled smoke. However, a sheriffs deputy who checked out the area around the neighbor’s house notified his superiors

at about five-thirty that he hadn’t found anything suspicious. That was less than two hours before the house was discovered in flames.

But no one reported seeing anything of Teresa that morning, or the family’s second car, a two-year-old yellow Datsun. Sheriff Ribar and other investigators began a statewide search for the missing five-foot, ninety-pound girl and the Datsun. The search was quickly expanded to a nationwide effort. Based on descriptions provided by her father and neighbors, Teresa was pretty, with shoulder-length dark hair, full lips, and the tiny build of a pixie.

The sheriff had good reason to be concerned. During a preliminary examination of the bodies at the scene, where he pronounced the victims dead, Medina County coroner Andrew Karson observed injuries that appeared to have been inflicted with a gun and knife. Consequently, he ordered the bodies transported to the Cuyahoga County Morgue in Cleveland, where more sophisticated facilities were available for autopsy.

After talking with Bickerstaff, investigators also publicly disclosed that six or eight guns were missing from a collection the foundry worker had kept in the house. One of the guns was a .357 revolver produced by Ruger, a popular German arms manufacturer.

A few days later a report from the state fire marshal’s department was released, with a formal finding in the case of arson. Gasoline had been used to set the fire.

A week after the blaze, Dr. Karson confirmed what Sheriff Ribar already knew. The mother and sons were not the unfortunate victims of an accidental fire. Sheriff Ribar and his investigators had a case of multiple murder and arson on their hands.

According to the autopsies, the victims were shot with a .357-caliber magnum shell, possibly from a Smith & Wesson, Taurus—or a Ruger. Several other scorched and blackened guns were found in the rubble of the

house, but it couldn’t be immediately determined if any of them was the murder weapon.

Both Dr. Marilyn Cebelin, who performed the autopsies, and Dr. Karson, had yet more chilling information to share with law enforcement authorities and the press. “The gunshot wounds may have been serious enough to be fatal, but the victims were alive following the shootings, and may have died as a result of smoke inhalation,” Dr. Karson disclosed. Carbon monoxide was found in Fred, Jr.’s blood, indicating he was still alive while the house was burning.

Metal fragments were found in Mrs. Bickerstaffs neck, and she also had a bullet wound in one foot. Fred, Jr., was shot in the head, chest, and shoulder and had suffered a groin injury that may have been inflicted with a knife. His brother Kenneth was shot once in the head, and stabbed ten times in the chest. Some of the stab wounds punctured his lungs. One rib was fractured, and several others showed signs of injury. The teenager’s left forearm and left ring finger were also slashed, injuries that Dr. Cebelin said were probably defensive wounds.

The coroner’s official finding stipulated that Mrs. Bickerstaff and Kenneth died of head injuries inflicted by gunshots. Fred died of a gunshot wound and carbon monoxide poisoning. He outlived his mother and sibling, surviving long enough to die of smoke inhalation during the fire.

The mother and sons had died horribly, at the hands of a killer acting in a frenzy of violence and hate. The slayings were an outrageous example of overkill, which can be an important tip-off to experienced homicide investigators that the killer probably wasn’t a stranger to the victims. Such unbridled ruthlessness is usually an indication of a strong emotional link between the victim and the perpetrator—or the grisly work of a madman. When burglars, home invaders, or professional hit men kill, they seldom kill with such savagery.

The idea of a slight teenager like Teresa falling into

the hands of such a killer, or killers, was chilling. But investigators quickly determined abduction wasn’t the only possible explanation for the girl’s ominous disappearance. They learned from her father, other relatives, and acquaintances, that she was a severely troubled teenager.

Her attendance at Cloverleaf High School in Medina had been sporadic during the past couple of years. School authorities said she was twice expelled for skipping school during the 1978-79 terms, and attended only the first few weeks in 1980. She simply wouldn’t show up for classes, a school spokesman explained.

During the early stages of the investigation, detectives also considered the possibility that the girl might have been involved with some sort of destructive occult practices or black magic cult. Although investigators had heard of occult ceremonies held at nearby Lake Chippewa, there was no indication that either Teresa or any other member of her family had any dealings with the cultists.

Of more concern, police quickly learned that Teresa was a streetwise nomad who had become entangled in the twin morass of drug abuse and prostitution before she was old enough to drive. She had been in almost constant trouble ever since she moved to Medina County with her family two years earlier from the blue-collar Cleveland suburb of Parma Heights.

She was already hooked on drugs at thirteen, and when she was fourteen, she ran away from home. According to the stories told to investigators, she hitchhiked cross-country to California, swapping sex to truck drivers for rides and meals. Shortly after she returned to Ohio in 1979, she entered a Cleveland hospital for treatment in its drug rehabilitation program.

While she was undergoing treatment, she met Eric J. “Scooter” Davis, a twenty-one-year-old black high school dropout from Cleveland. Almost immediately they began hanging around together. And on at least

one occasion she took her new boyfriend home to meet her family in Medina County. Teresa’s parents weren’t pleased with the budding romance, and, Teresa would later claim, a few days before the murders and fire, her father angrily chased Davis off the property.

Several days after the arson murders occurred, Mrs. Bickerstaff and her sons were buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Lodi. Her husband was comforted at the services by other family members and friends. His daughter was still missing.

Three classmates of the brothers in the Cloverleaf school district’s eighth and ninth grades started a memorial fund to be turned over to the father of their friends. The brothers were athletic and played football for the school district.

Meanwhile, Sheriff Ribar’s immediate concerns were the search for the missing girl and the Datsun. After the first few days of the nationwide search failed to produce results, the sheriff had Teresa charged in juvenile court with unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. Spokesmen pointed out to reporters that the charge was a formality, a means for law officers to legally detain the driver and vehicle if they were spotted.

As the investigation continued, the Ohio State Fire Marshal announced a $10,000 reward for arrests in connection with the arson murders. Investigators were hopeful that the reward would help, but at that point the key to solving the perplexing case appeared to be tied to finding the missing girl and the car.

On October 3, 1980, U.S. Customs officials alerted by the All Points Bulletin stopped the yellow Datsun as it was being driven across a border checkpoint at Detroit from Windsor, Canada. The car was being driven by a young black man, with a young white woman as a passenger. Several guns and a switchblade knife were found inside the vehicle. The knife was bloodstained, although laboratory technicians were unable to determine in later tests if the blood was human.

After lengthy questioning, the pair identified themselves as Teresa Bickerstaff and Eric Davis. Sheriff Ribar sent Detective James Williams to Detroit, where he was joined by Pat Berarducci, a U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms special agent from the agency’s Cleveland office. Together, they interrogated the two fugitives.

Within an hour the runaway lovers were tape recording detailed statements, pinpointing their roles in the ruthless arson-slayings. Teresa confessed that she killed her mother and brothers while her boyfriend started the fire to cover up the murders. Davis made a second tape-recorded statement two days later.

According to Teresa’s account, she was planning to leave home, and her boyfriend arrived at the house some time after two A.M. to pick her up. He loaded her father’s .357 Ruger, which she had taken from a dresser drawer, and gave it to her. Long before the couple was apprehended, investigators had already recovered a box of .357 magnum cartridges from the recreation room of the fire-gutted house. Crime technicians turned up three of Teresa’s fingerprints on the inside flap.

Continuing her story, the girl said she carried the revolver with her when she walked upstairs to pack some clothes. Then her mother awakened and called to her from the master bedroom.

“I don’t know what happened. She just went off, and I went off, and the gun went off,” Teresa explained. The teenager said she was frightened.

Kenneth began yelling when he heard the gunshot, and she went into his room and shot him, she said. Then Fred, Jr., rushed at her.

“Freddy came running at me with a pillow, calling me a bitch and a whore because he saw my mother drop. He saw her die,” she related. She said she shot him, then, without even stopping to think, she shot each of the boys a second time.

“Freddy was just moaning and stuff and making me

crazier than I already was,” she stated. “I kept screaming, and they weren’t dying, and it was tripping me out.”

The teenager said that as she returned downstairs with her clothes, “Freddy was still moaning, and Scooter was saying, ‘He’ll die! He’ll die!’” Curiously, despite the knife wounds found on the bodies, Teresa said nothing at all about stabbing any of the victims.

Davis also claimed the murders weren’t planned. He said he had agreed to meet his girlfriend at the house, and they intended only to leave together and take the car. But he admitted loading the revolver and giving it to her while they were in the downstairs living room. Then they walked upstairs together.

Davis didn’t describe the attack on the boys, but he later told officers, “Teresa was running around hollering that her brother wasn’t dead. She shot him again.”

The situation became so confusing that he couldn’t remember everything in its proper sequence, the Cleveland youth told his interrogators. “I just tried to get her out of there as fast as I could,” he said. “I went back into the house and just threw a gas can and lit a match. I did it on the spur of the moment. I was scared, just scared.”

In his initial statement, Davis said he tossed the gun out the window of the car on the way to Detroit. When he was questioned again two days later, however, he changed his story and claimed he gave the murder weapon to a friend in Cleveland he identified only as “Rick.”

Teresa’s life at home was so unbearable that she decided to leave and asked him to come pick her up, Davis continued. He claimed her father beat and verbally mistreated her. Davis said that when he arrived at the house to pick her up on August 26, her face and arms were bruised. He also quoted Teresa as telling him that earlier that day her brother, Fred, Jr., offered her to a buddy of his for sex. When she broke away from the

boys and ran to her room, her mother laughed, according to the story.

The sweethearts explained that they crossed into Canada at Niagara Falls the day after the murders. Davis, who had studied welding, worked for a while in an auto body shop, and also tended cattle for a time while they were in Canada. But after he lost both jobs, they decided to return to the United States and head for Mexico.

Two days after their apprehension at the border, Teresa and her boyfriend were returned to Ohio and locked in separate cells at the old red-brick Medina County Jail behind the courthouse in Medina.

Teresa was charged in Medina County Juvenile Court with three counts of aggravated murder, and grand theft auto. Davis was held on temporary charges of auto theft and possession of a stolen credit card.

When Teresa was escorted from the county jail to juvenile court for a hearing to establish just cause for holding her in temporary custody, she was accompanied by law enforcement officers and a clergyman. The Reverend John Hood, pastor of the Lodi United Church of Christ, told reporters he had talked and prayed with her at the request of her father.

One week after the couple’s apprehension, a Medina County grand jury indicted Davis on three counts of aggravated murder, four counts of aggravated robbery, and two counts of receiving stolen property. Bail was set at $100,000. At his arraignment, he pleaded not guilty to all charges. Four counts of aggravated arson would later be added.

Possible grand jury action against Teresa was temporarily delayed until Medina County Juvenile Court Judge H. Dennis Dannley determined if she should stand trial as a juvenile or as an adult. A few weeks later he ruled that she would be treated as an adult, and the grand jury indicted her on three counts of aggravated murder.

Attorney James R. McIlvaine of the nearby town of Wadsworth was appointed by the court to represent the girl, and he requested a delay of arraignment until she could be psychiatrically evaluated. The lawyer told Common Pleas Court judge Phillip Baird that there were strong suggestions she suffered severe mental problems and was not mentally capable of assisting in her own defense. Over the protests of the prosecution, Judge Baird granted the continuance, and established bail at $100,000, the same amount her boyfriend was being held on.

Several weeks later, Teresa entered pleas of not guilty on all charges. Mcllvaine explained to reporters that results of his client’s psychiatric testing weren’t yet complete, and her not guilty plea didn’t preclude the possibility of a later change of plea to not guilty by reason of insanity.

Davis meanwhile busied himself in his cell composing a series of nineteen handwritten letters to his girlfriend. The notes eventually wound up in the hands of Teresa’s defense lawyer.

Early in the new year, as Teresa and her boyfriend remained in jail unable to raise bail, Medina County’s newly elected prosecutor, Gregory Happ, filed additional charges against Davis. Davis, who was represented by Cleveland attorney James Willis, was named on three new counts of aggravated murder by reason of aggravated robbery, and on three counts of aggravated robbery. He entered pleas of not guilty to the new charges.

Happ, who had defeated a two-term incumbent, told reporters he decided the additional charges should be filed after reevaluating the evidence against the couple.

On April 22, 1981, almost seven full months after the murders, Davis’s trial began in the old courthouse that dominates the Medina town square. The shocking slayings of Mrs. Bickerstaff and her sons, and the arrest of her daughter and Teresa’s boyfriend, was already the most sensational murder case in the history of the county. A crowd of curiosity seekers was waiting on the blustery mid-spring morning when the courthouse doors opened. And the trial promised to add even more titillation, and horror, to what was already known by area residents about the family tragedy.

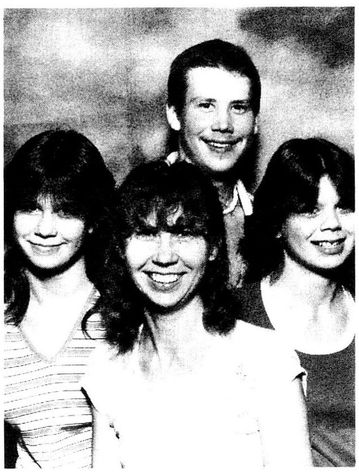

Nancy Knuckles surrounded by her children, Debbie (left), Bart and Pamela.

(© Chicago Tribune)

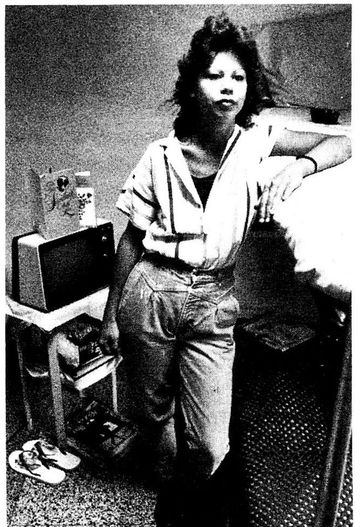

Pamela Knuckles, at the Dwight Correctional Center, after sentencing for the slaying of her mother.

(© Chicago Tribune)

Susan Cabot, in the 1958 film, War of the Satellites. (The Kobal Collection)

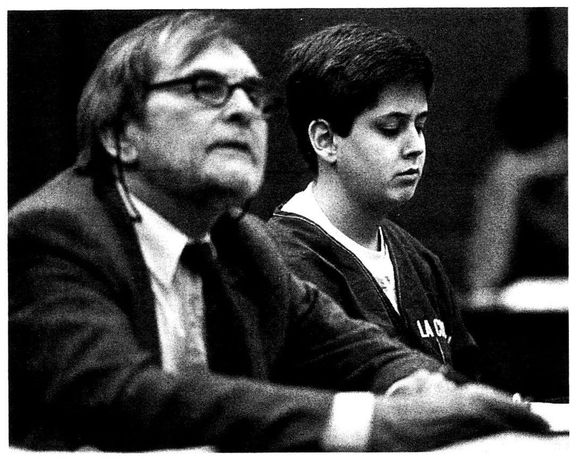

Timothy Scott Roman with his attorney during a hearing in Van Nuys, California, prior to Roman’s first trial for the slaying of his actress mother, Susan Cabot.

(Scott Garrity/Los Angeles Daily News)

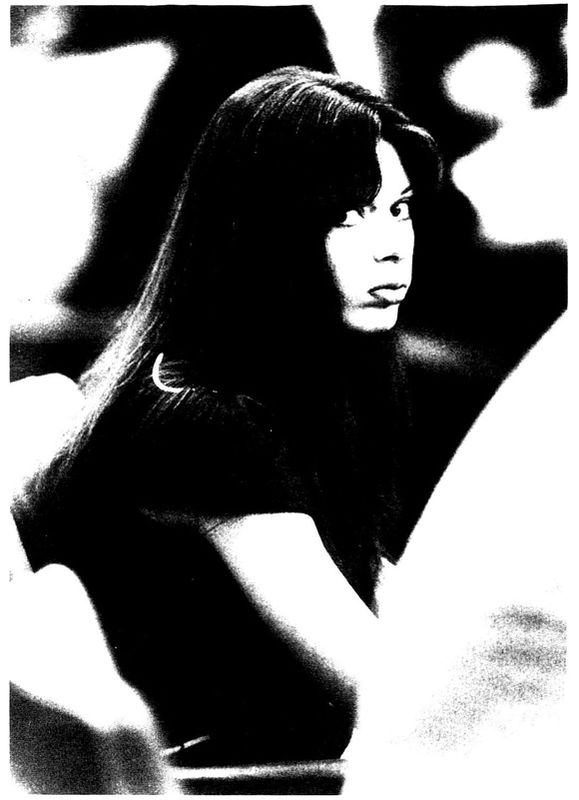

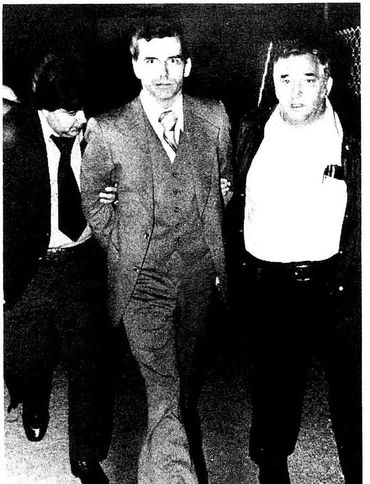

Teresa Bickerstaff during her trial for the murder of her mother and two brothers. (Courtesy of Medina County Gazette)

Richard Jahnke with Sharon Lee Tilly (left), a child abuse worker, as they leave the Laramie County Courthouse after the jury began deliberations to determine if Jahnke was guilty of the shooting death of his father. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Deborah Jahnke (right) and her mother Maria talk about their family’s experiences. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Cheryl Pierson and fiancé Rob Cuccio, with the engagement ring he gave her on the day she completed serving her jail term.

(Newsday photo, courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Syndicate International)

Sean Pica, six months after beginning his prison sentence for the contract murder of James Pierson. (Newsday photo, courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Syndicate International)

Ross Carlson (left) with attorney David Savitz at a hearing in Littleton, Colorado, to determine if Carlson was mentally capable of helping in his own defense on charges that he murdered his parents. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Patty Columbo being led from the Criminal Courts Building in Chicago to the women’s lockup after sentencing for the murders of her parents and little brother. (Ray Gora, © Chicago Tribune)

Frank DeLuca, Patty Columbo’s boyfriend, being led from the court after having been found guilty of murder. (© Chicago Tribune)

Happ rejected a last-minute plea bargain offer by Davis’s defense lawyer shortly before the trial began. The prosecutor confirmed to the press after the conclusion of the trial that Willis had offered to have his client plead guilty to three charges of manslaughter. But Happ was determined to seek convictions against Davis on the more serious felony murder charges which would carry much longer jail terms.

Although police and prosecutors had been unable to locate the Ruger .357 believed to be the main murder weapon, they had collected a dazzling array of other evidence for presentation in the trial. And they had rounded up dozens of potential witnesses.

Attorneys took two days to select a jury of eight men and four women. The fireworks began two days later, with accusations during opening statements by the defense that incest allegedly committed by Teresa’s father was at the heart of the case. According to Willis’s impassioned opening, Davis was an innocent bystander who was struck by the fallout when the girl’s long-festering anger and hatred exploded into violence. The lawyer painted a word picture of his client as a black man who fell in love with a troubled girl and became a victim of forces set in motion by someone else when he tried to help her. The lawyer claimed the evidence would show how a family could be destroyed “by sex, incest, and bigotry.”

Willis claimed the girl was sexually abused since she was an eleven-year-old sixth-grade student, and that the behavior continued until she was fourteen. At the age of fourteen she was already a drug addict, and ran away to

Cleveland, where she became involved with a pimp and worked as a prostitute, he said.

The defense lawyer said the girl continued her prostitution, including stints at truck stops in Chicago and Wisconsin, before returning to Cleveland and entering the drug treatment program at a psychiatric hospital. It was there she met Davis, who was visiting the hospital, Willis said.

“Eric Davis broke her of her drug addiction and prostitution and took her back to her family,” he declared. According to Willis, the efforts of the young miracle worker who rescued the troubled girl from the streets weren’t appreciated, however, and when she returned home, she was greeted with brutality. So the couple planned to run away together, and never planned to kill anyone. But the innocent scheme went terribly wrong when Mrs. Bickerstaff awakened as her daughter was preparing to pack her clothes.

“Teresa lost it and shot her. And then she shot her brothers,” Willis declared.

“The evidence will show that Eric Davis started a fire, and that dead people burned,” he told the jury. The lawyer conceded only that his client set the fire, and firmly denied that Davis committed murder.

Happ, who was joined at the trial by Assistant Prosecutor John Porter, used his opening statement to portray Davis as the puppet master who set up the crime. “Eric Davis instructed Teresa Bickerstaff to carry out his plans with him,” Happ declared.

The prosecutor told the jury that Davis confessed telephoning the girl earlier that evening and instructing her to gather up guns that were in the house, “just in case”; that he admitted loading the murder weapon; admitted standing next to Teresa when she shot her family members; and confessed pouring the gasoline.

Teresa’s father was the first witness called by the prosecution, and he identified as his property the missing .357 Ruger and several other pistols and rifles, ammunition,

and the switchblade knife found in the Datsun when the couple was taken into custody.

During cross-examination, however, Judge Baird sustained objections from Porter and forbid Willis to pursue questions about the allegations of incest.

When Bickerstaff was asked if he objected to his daughter’s relationship with the defendant because Davis was black, he replied: “I felt the same way you would feel if your daughter was marrying a white man. I don’t believe in mixed marriages,” he told the black defense attorney.

Prosecutors scored points for their case against the defense allegation that Bickerstaff had physically abused his daughter, when a teenage pal of the brothers testified he often saw Teresa around her home and never noticed bruises or other signs that she had been beaten. The testimony seemed to contradict both Willis’s opening statements that the girl’s father physically abused her and Davis’s claims that he and Teresa planned to run away together because she was fed up with being beaten.

Peter Petrokis, an Ohio State Fire Marshal’s investigator, testified that he found evidence of three different fires in the Bickerstaff house. Traces of gasoline were found in an upstairs hallway, the stairway, on the main floor, and on Mrs. Bickerstaff’s clothing, he said. The witness explained that the fire smoldered for several hours in the enclosed house until all the oxygen was exhausted, and the pressure caused an explosion that shattered the windows.

“The fire was not accidental. It was caused by a person or persons,” he testified.

Dr. Lester Adelson, a deputy Cuyahoga County coroner, disclosed during testimony that both Kenneth and Fred, Jr., may have been alive when the fire roared through the house. Expanding on the autopsy report which showed Fred was alive, because the level of carbon monoxide found in his bloodstream revealed he’d

been breathing smoke, Dr. Adelson said that blisters found on Kenneth’s thigh indicated he was still living when the fire occurred.

“A person must be alive to form water blisters. Dead people don’t blister,” he explained. As Dr. Adelson identified gunshot and stab wounds on the bodies, blowups of color photographs taken of the brothers shortly before the autopsies begun were projected on a screen for the jurors. Repeated efforts by Willis to block their use were turned down by the judge.

During cross-examination, Willis attempted to get the pathologist to pinpoint a single cause of death for Fred, Jr., but Dr. Adelson refused to refute the autopsy report. “How much did the carbon monoxide contribute to Fred’s death, is the question you’re asking,” he responded at one point. “The answer is both were causes —the gunshot and the carbon monoxide.”

The witness indicated, however, that it wasn’t known if the teenager could have survived the shooting if there had been no fire and carbon monoxide in his lungs. The autopsy had shown there was soot in the boy’s throat. “Fred was alive in the fire and breathing smoke. Breathing is living,” the pathologist said.

The point Willis was attempting to make was an important one. Teresa had admitted during her interrogation in Detroit that she shot her mother and brothers. Davis admitted setting the fire. Consequently, if the victims died from gunshot wounds, it would indicate that Teresa was the actual killer. If carbon monoxide or burns resulting from the fire caused the deaths, then direct blame could be placed on the defendant.

At the conclusion of the defense’s case, Judge Baird directed acquittals for Davis on two charges of aggravated murder by arson in the deaths of Mrs. Bickerstaff and her son Kenneth. The jurist ruled that there was insufficient evidence to support the charges.

The two witnesses whom spectators were most anxious to hear from, however, were the defendant and the

pretty young woman who reputedly joined with him in the slaughter of three members of her family. Both were called as witnesses by the defense. But Teresa’s appearance on the witness stand was brief and disappointing. Citing the advice of her attorney, she exercised her constitutional rights under the Fifth Amendment to refuse to answer questions on grounds her statements might be self-incriminating.

The testimony of Davis, who was the last witness called in the trial, was longer and more revealing. He repeated his claim that the slayings were unplanned, and that he and his girlfriend were merely preparing to run away together. And he continued to blame the shooting and stabbing on Teresa.

When Porter asked during cross-examination if the defendant had seen Teresa’s brothers after they were shot, he replied, “Just in passing. I didn’t stop to look.”

Porter asked if Teresa had told him after the shootings that the boys were still alive. “Yes, something to that effect,” he responded.

Davis explained that he was walking down the stairway from the second-floor bedrooms carrying two bags of his girlfriend’s clothing when he heard another shot. “But you said five or six times that you heard no other shots,” the prosecutor reminded him. Porter demanded to know whom he had lied to, the law enforcement officer he had made the earlier statement to, or to the jury.

“I sort of twisted it a little bit in the statement,” Davis said of his confession.

Continuing his account under the sharp questioning of the assistant prosecutor, Davis said that after hearing the last shot, he took the weapon from his girlfriend and walked into Mrs. Bickerstaff’s bedroom to collect additional guns kept there. He said he draped a sheet over the dead woman’s body.

“Did you look at her?” Porter asked. “I didn’t stare,” the defendant answered. Continuing to reply to questions,

Davis said she wasn’t moaning, and he didn’t check to see if she was dead or alive. And he didn’t call for an ambulance.

Davis told the court he reloaded the empty gun, took a set of car keys from Mrs. Bickerstaff’s purse, and went downstairs with Teresa and into the garage where the Datsun was kept. Before taking the car, however, he picked up a five-gallon can of gasoline from the garage, hurled it into the hallway, and tossed a lighted match after it.

A look of astonishment crossed the assistant prosecutor’s face at the testimony about the gas can and the match. “Are you telling the jury you didn’t pour any gas?” he asked. “Yes sir,” Davis responded.

It was a perplexing statement that seemed to conflict with the arson investigator’s earlier testimony about finding traces of gasoline at several locations in the house. But it wasn’t the only bit of Davis’s testimony that conflicted with the statements of earlier witnesses. He claimed neither he nor his girlfriend stabbed her brothers. The coroner had testified, however, that Kenneth was stabbed more than a dozen times, and Fred, Jr., was stabbed once.

Turning to the subject of Teresa’s illicit substances abuse, Porter asked the defendant if he had given her any drugs. “No more than reefer,” Davis said, using a street name for marijuana.

Porter asked if he had ever given her PCP, a powerful animal tranquilizer that street users refer to as Angel Dust.

“Probably on some occasions, yes sir,” Davis conceded.

Porter asked if she got very high when she was using the drugs. “Nothing she couldn’t handle,” the defendant replied.

On a sunlit Friday morning and afternoon eight days after the trial opened, the defense attorney and the

prosecuting team delivered their summations to the jury.

Willis continued to point his finger at racism for a share of the blame in the tragedy by recalling his exchange with Bickerstaff over the question of interracial marriage.

“Deep are the roots of prejudice and bigotry,” he intoned to the all-white jury. “And they must be deep in the hearts of the Fred Bickerstaffs of this world.”

The defense attorney also attacked his client’s confessions, claiming that Davis was hoodwinked by a slick-talking BATF agent. “He signed away his rights so many times it was unbelievable. They were trying to dig a hole for him,” he complained.

When it was the prosecution’s turn, Porter scoffed at the idea that Davis was motivated to go to the Bickerstaff house on the night of the murder by a desire to protect Teresa.

“Is he a protector? Does a protector give his lady friend Angel Dust? Does a protector plan to rob his girlfriend’s house?” the assistant prosecutor demanded. “He’s not a protector. He’s a manipulator. All he had to do was pull the strings on that puppet.”

Porter observed that several members of the defendant’s family had attended every day of the trial. “But consider the fact that the Bickerstaff family could not be here,” he said. The deputy prosecutor also defended Teresa’s father against the accusations by the defendant and defense attorney that Bickerstaff had sexually and physically abused her. “Mr. Fred Bickerstaff only came in here to identify property, and Mr. Willis subjected him to uncorroborated innuendo,” Porter complained.

The jury deliberated more than eleven hours over parts of two days before informing the court at about seven o’clock on a Saturday night that they had reached a decision. The panel returned verdicts of guilty to three counts of aggravated murder, three counts of aggravated robbery, and four lesser charges. The jury returned

not guilty verdicts on three charges of aggravated arson. Flanked by his attorney, Davis showed no emotion as Judge Baird read the verdicts. The judge scheduled sentencing for eight weeks later, at the end of June, in order to give authorities with the Medina Adult Probation Department time to make an evaluation and recommendation.

Each of the six controversial new felony charges filed against Davis after Happ assumed the office of prosecutor were included in the convictions.

Davis was permitted to confer briefly with his attorney, and to hug his mother and other members of his family before he was led from the courtroom by sheriffs deputies.

According to the Ohio state criminal code at the time, a life sentence was mandatory for an aggravated murder conviction. The judge, however, would have considerable leeway in determining whether Davis’s various sentences should be served concurrently or consecutively. Depending on the judge’s decisions, the convicted man could eventually be released from prison while he was still relatively young or he could remain behind bars until old age or death.

When Davis reappeared in court on Monday morning, June 29, his attorney asked the judge to order all the prison terms served concurrently with the life sentences. Willis pointed out that his client was from a good family and had no previous criminal record. “Mr. Davis was caught up in something bigger than he is. I ask the court to be merciful,” the Cleveland attorney pleaded.

Davis declined an opportunity to make a presentencing statement.

A few minutes later Judge Baird ordered him to serve three life terms in prison for the murder convictions, and three terms of from five to twenty-five years in prison on the robbery counts. Davis was also ordered to serve separate five- to twenty-five-year terms for involuntary

manslaughter and for aggravated arson, and terms of from two to five years each for grand theft and for receiving stolen property. The judge stipulated all the sentences to be served concurrently, except for the last two counts, which were to be served after the life terms. And he ordered that Davis be given credit for 269 days already served in jail.

Despite what appeared to be a staggering number of years extending more than three lifetimes, the sentencing order was framed so that Davis would become eligible for parole in about fifteen years.

A few days after sentencing, Davis was transferred from the county jail behind the courthouse to the Columbus Correctional Facility, where his permanent assignment to a state prison would be determined.

Teresa wasn’t as easy to bring to trial as her convicted sweetheart. The court was buried under a barrage of motions and a maze of mind-boggling delays that resulted in five postponements of trial dates.

Her trial was about to begin on May 19, less than three weeks after Davis’s conviction, when she pleaded guilty on the scheduled opening day to the single charge against her of grand theft for stealing the family Datsun and the guns. It appeared that the surprise move was a brilliant maneuver by the defense, because McIlvaine followed up the court’s acceptance of the plea by asking that six other counts linked to the theft charge be dismissed. The defense lawyer argued that since those charges stemmed from a single theft she had already pleaded guilty to, trying her for those reputed offenses would violate her constitutional rights by placing her in double jeopardy.

Judge Baird agreed with the argument and, over prosecution objections, dismissed three counts of aggravated murder and three counts of aggravated robbery. The prosecution appealed the judge’s decision, and was subsequently upheld in the higher courts. The Ninth Ohio District Court of Appeals in nearby Akron ordered reinstatement

of the charges. After Ohio’s Supreme Court refused to hear a defense appeal of the reinstatement, Teresa’s trial finally got under way on January 20, 1982. Her mother and brothers had been dead nearly a year and a half.

Despite the bitter cold of the midwinter day, men and women began lining up as early as seven A.M. to get seats in Judge Baird’s courtroom for the trial that experts were predicting would last as long as three weeks. This time, not only Davis, but Teresa as well, were expected to tell their stories. The Ruger .357 was still missing.

Despite some early concern that the pervasive publicity surrounding the case might make it impossible to pick an impartial jury from Medina County, three days later a panel of nine women and three men was sworn in.

During jury selection, McIlvaine had cautioned prospective members of the panel that some of the evidence would be “ugly, gruesome, and shocking to our senses of decency and our moral codes.” Prospective jurors were closely questioned about their attitudes toward interracial couples and a defendant who had been a runaway and prostitute, abused drugs and skipped school. One man was dismissed by McIlvaine after admitting he disapproved of interracial couples.

When opening arguments began the next day, the courtroom was packed with print and electronic media reporters from throughout northern Ohio, as well as other spectators, anxious to hear the most notorious murder trial in the history of rural Medina County. People who couldn’t squeeze into Courtroom Number 2 waited in the hallway.

McIlvaine had barely begun his statements when he told the jury that the gunman who shot the Bickerstaffs was Davis, not the eighteen-year-old girl the prosecution claimed was the shooter. Teresa let her boyfriend in

the house, but Davis pulled the trigger, the lawyer claimed.

The defense attorney said Teresa was on the main floor when Davis walked upstairs with the revolver and she suddenly heard gunshots. Tracing her new account of the events, McIlvaine said: “She has no knowledge of who has been shot. Her brothers have weapons. She runs upstairs and sees her mother lying there. She dropped to her knees and cradled her mother in her arms.” Jurors listened quietly, their faces immobile as he outlined the touching scenario.

McIlvaine said his client lied in her earlier statements to police in an effort to protect the man she loved. But she decided she couldn’t continue the charade after Davis wrote to her in jail asking her to provide further cover-up for him by claiming her mother and brothers had already been shot before she even let him into the house, the defense lawyer continued.

As Willis had done, McIlvaine also accused Teresa’s father of initiating an incestuous relationship with her when she was in the sixth grade, and continuing the reputed sexual abuse for almost three years. The lawyer blamed what he said was Teresa’s sexual abuse for her behavior change and troubles with truancy, running away, drugs, and prostitution.

The prosecution hadn’t changed its contention that Teresa herself had wielded the gun and the knife against her mother and brothers, however. In Happ’s opening statement, he pointed to the taped confession she made to investigators in Detroit, and assured the jury that the statement would be placed into evidence to show she had admitted the shootings. He said testimony would also be introduced to back up the statement.

“We will prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Teresa Bickerstaff murdered her mother and her two brothers,” the prosecutor promised.

Teresa’s father got his chance to deny the outrageous accusations against him when he was called to testify as

the first prosecution witness. During direct questioning by Porter, then during cross-examination from McIlvaine, the sturdy widower denied that he had ever had sexual relations with his daughter.

“I never had sexual intercourse with Teresa,” he told the prosecutor. When Porter asked him to face the jury and answer the question, he turned to look at the panel and, speaking in a strong, audible voice, firmly repeated his denial. Prosecutors would later support Teresa’s father’s strong denial, telling reporters that the incest allegation was never established.

As he had done in the earlier trial, the Cleveland factory worker identified guns found in the house by investigators, and the switchblade knife taken from the Datsun after his daughter and her boyfriend were apprehended in Detroit. He testified that he had owned a Ruger .357. And he explained the floor plan of his house.

At the prosecutor’s request, Bickerstaff read the jury two letters his daughter wrote to him shortly after she was locked up in the county jail. The letters, which the witness identified as being in Teresa’s handwriting, contained an explanation of the events that occurred in their house on the night of the murders. It was similar to the statement she had given to investigators when she was questioned in Detroit.

In the notes, she said she loved her mother and brothers, but didn’t want her father to blame her boyfriend, whom she referred to as “Scooter.” Without him, she said, she might have committed suicide. His race was not important to her. That’s just the way he was born.

Later, when the prosecution showed pictures of the family to jurors, Teresa broke into tears. Her sobbing increased as the panel was shown a photo of her brothers in their baseball uniforms. And she turned her head away when the prosecutor produced gruesome color slides for the panel of the horrendously charred bodies of her mother and brothers. Even some of the jurors

had trouble dealing with the unpleasant images, and their faces paled while they grimaced in revulsion.

Several other witnesses were called by the prosecution during the first day of testimony, including neighbors who stated that they had seen the defendant at various times before the fire but never noticed any bruises on her face or body. One of the neighbors described her as a little shy.

In later testimony, Dr. Cebelin described the injuries to the victims which she noted during the autopsy. The former Cuyahoga County pathologist said Mrs. Bickerstaff was so badly burned that it wasn’t possible to determine how many times she was shot in the head. She testified that Kenneth was stabbed before he was shot. And she indicated that Fred’s groin injury may not have been a stab wound, but damage inflicted by the fire. The body was in such poor condition that it wasn’t possible to make an exact determination.

An uncle of Teresa’s from Toledo told the jury that he and his family stayed overnight at the Bickerstaff house earlier on the week of the murders and he overheard his niece in a telephone conversation at about two A.M. She mentioned that her aunt and uncle were there, then appeared to reply to a question. He quoted her as saying, “Thursday? I’ll think about it.” Earlier testimony had already established that the murders occurred in the predawn hours of Friday morning.

The uncle told the jury Teresa was treated like a queen at home, and spent most of her time watching television. He also recalled, however, that one of the boys confided to him that he hated his sister. While he was talking with Teresa once, she told him a story about a pimp who was shot to death in front of her by a woman in Cleveland. She didn’t appear upset while she was recounting the incident, the witness said.

Just before resting their case, prosecutors played the tape of Teresa’s confession in Detroit. In the confession she admitted shooting her mother and brothers, gathering

up her clothes, and climbing into the car in the garage. Her boyfriend asked if there was any gasoline around, then disappeared back inside the house. He returned a few minutes later and they drove away, according to the account.

McIlvaine called the defendant to testify on the sixth day of the trial, and she told the jury she lied in her confession to police to protect her boyfriend. Davis murdered her mother and brothers, she said.

Responding in a voice that was soft but audible to questions from her attorney, she claimed she hatched the idea of taking the blame for the shootings while she and Davis were still in Canada. “Well, I had decided it would be better for me to take the case because I was a juvenile and had been put away three times,” she explained to the silent jury. “Scooter was older and black. It would be harder on him.”

She said she changed her mind after Davis wrote her in jail asking her to say he wasn’t even in the house when the slayings occurred. Teresa’s lawyer read two of Davis’s letters for the jury, suggesting that she take the blame and plead insanity.

Teresa said she had already done so much for her sweetheart that it hurt her feelings when he asked for still more. The teenager continued to claim, however, that she and Davis never planned to kill anyone, but were merely preparing to run away. She said they decided she should leave home after her father chased her boyfriend down the driveway, then beat her.

The faces of the jurors were set and grim as she continued her chilling account, testifying that after her boyfriend arrived at the house, he loaded the gun she had stolen from her father’s dresser and they talked until her mother called from upstairs. Teresa said she started upstairs, but Davis stopped her and said he would talk to her mother instead.

“He went upstairs, and the next thing I heard was a gunshot,” she related. Teresa said she ran upstairs,

found her mother on the floor, and bent over to hold the stricken woman in her arms. She claimed that her memory of events immediately after that were hazy or nonexistent. “I heard other gunshots,” she said, allowing her voice to trail off slightly. “I don’t know if that was in my mind. I wasn’t all together.” Full awareness didn’t return to her until her boyfriend had taken her to the garage and helped her into the car, according to the account.

As Teresa testified, she was dwarfed by the witness chair and appeared much younger than eighteen, her age at that time. But the story she was telling was no little girl’s fairy tale. It was the stuff of nightmares, of real-life ogres and bloodthirsty trolls. She told the jury about her life as a prostitute, how she ran away from home when she was fourteen and swapped sex for rides with truck drivers, about her drug abuse, and about the abortion she had when she was sixteen. And she accused her father of sexually abusing her when she was in the sixth grade, and continuing to bother her almost every night until she was fourteen.

When Porter asked during cross-examination if she saw her brothers after they were shot, she replied that she didn’t. “When I went upstairs, I didn’t even see Scooter. I only remember seeing my mother.”

Porter asked if she knew who shot the boys. “It’s obvious, I think, who shot them, but I didn’t see it,” she responded. When Porter continued to press for a name, she replied, “It had to have been Scooter.” Throughout her testimony, she referred to Davis by his nickname.

Turning to a new area of inquiry, Porter asked her if she had once threatened a woman she was living with in Cleveland with a gun. The witness denied that she had.

But the prosecution called a rebuttal witness, whose testimony indicated the teenager was lying. The Cleveland woman said Teresa pulled a gun on her during a quarrel and complained that she was fed up with being given orders and with her friend’s efforts to run her life.

She quoted Teresa as saying she didn’t want to hurt her but was being forced to. The girl once fired the gun out a window of the house at a parked pickup truck, and was proud that she knew how to operate the weapon, the witness said. She explained that Teresa and Davis lived with her and her husband for three months. Teresa was in tears when the testimony was concluded.

The only other witness called by McIlvaine was a young woman who testified that she and the defendant were pals when they were in the sixth grade and Teresa had told her about the reputed sexual abuse.

Defense attorney McIlvaine didn’t ask for an acquittal during his summation. He told the jury that his client was guilty of manslaughter, but that she was telling the truth when she testified, repudiating her earlier confession and blaming Davis for the murders. Her confessions didn’t match the physical evidence, he said. “Had they looked further, had they not closed the case, they would have seen that.”

According to the scenario the defense attorney outlined for the jury, Davis shot Teresa’s mother and brother Fred, and when he ran out of bullets, stabbed Kenneth. Once Kenneth was injured and unable to defend himself, Davis then reloaded the gun and fired the fatal shot into the thirteen-year-old’s head.

McIlvaine also pounced on the absence in his client’s early confessions of any mention of stabbing the victims. “The only reason you wouldn’t tell the truth if you are, as they say, confessing to everything, is because you didn’t do it. Why not tell?” he asked. “It’s no more heinous than anything else you’re telling.”

Finally turning to the allegations of incest, the defense attorney told the jury that when his client was twelve years old, her father had planted “the seeds of destruction” that culminated in the tragedy of the murders.

The prosecution team painted a different picture for the jurors than the scenario outlined by McIlvaine, insisting

that the defendant shot her mother and brothers and was guilty of premeditated murder. In his closing argument prior to the defense summation, Happ told the jury the defendant lied when she testified her boyfriend did the shooting.

The prosecutor also pointed to her statements to police that she shot her brothers a second time because she wanted to end their suffering, as evidence of premeditation. “She had to take the time to think that she wanted to put them out of their misery,” he declared.

Asserting she committed the “ultimate theft,” he declared: “She stole Fred Bickerstaff’s wife and his two sons. They are guilty of loving her, and for that they paid the ultimate price.”

Speaking in rebuttal after the defense’s closing, Potter cautioned the jury not to make their determination on the basis of a side issue in the case, such as the allegations of incest. “If you allow Teresa Bickerstaff to walk out of here on manslaughter, it cannot be based on the evidence heard,” he declared. “It could only be because you decided on a collateral issue that has nothing to do with this case.”

The jury deliberated twelve hours over portions of two days before returning with a package of Saturday afternoon verdicts. Teresa remained seated quietly beside her attorney as Judge Baird read the findings of guilty to six charges of murder, including three by reason of aggravated robbery and three charges of aggravated robbery. She was found not guilty of aggravated murder by premeditation. The verdicts represented almost a total victory for the prosecution. The three murder convictions linked to robbery carried mandatory life prison sentences.

As Teresa was led from the courtroom back to the jail to await sentencing, she showed little emotion. She was composed, as she had been throughout most of the grueling seven-day trial. As the defendant in the grisly and lurid murder trial, she behaved like a near perfect ice-maiden,

except for the two brief occasions when she broke into tears as the grisly slides of her murdered brothers were shown and her former friend testified against her.

Seven days after the jury’s decisions were reported, she was led back into the courtroom, where Judge Baird sentenced her to multiple prison terms designed to keep her behind bars for more than thirteen years before she would become eligible for parole in 1995.

The sentences included a life term for the murder of her mother; twin fifteen-years-to-life terms for the murder of her brothers; five-to-twenty-five-year terms on each of the aggravated robbery convictions; and two-to-five years on the grand theft she had pleaded guilty to for stealing the car and guns. Judge Baird ordered all the terms to be served concurrently, except for the two fifteen-year-to-life sentences in her brothers’ slayings. And he gave her credit for the 491 days already spent in jail.

A few days later Teresa was driven to the Marysville Reformatory for Women a few miles northwest of Columbus, to begin serving her sentence.

For more than two years McIlvaine carried his client’s case through the state’s appeals system all the way to the Ohio Supreme Court. In November 1982 the Ninth District Court of Appeals set aside her sentences on one count of aggravated robbery and on the grand theft conviction. The other convictions were upheld, and the actual minimum time to be served before becoming eligible for parole was unchanged.

A few months earlier the high court had upheld Davis’s convictions.

Early in 1984 the Ohio Supreme Court voted in a unanimous seven-to-nothing decision, upholding Teresa’s remaining convictions.

More than five years later the lurid case was recalled once more when the long-missing murder weapon was at last recovered by police in Ohio’s capital city. In July

1989, when a woman attempted to hock a .357-caliber revolver in Columbus, the pawn shop operater asked for a police check of the serial number to determine if it was listed as stolen. The National Law Enforcement Computer matched the weapon with the number on the gun used in the nine-year-old triple murder.

Medina County’s new prosecutor told the press he planned to obtain a court order to have the gun destroyed.