Francis Guy, Tontine Coffee House, N.Y.C. (detail), ca. 1797.

Colony of New York Five-Pound Note (detail), 1776.

ON THE MORNING OF MARCH 15, 1784,

a group of men gathered in the Merchant’s Coffee House on the southeast corner of Wall and Water Streets in New York City. Three weeks earlier they had assembled on the same spot and resolved to “establish a bank on liberal principles.” This morning, the new bank’s subscribers—those who had pledged to buy into the stock of 500 shares, thereby becoming the bank’s owners—came together to elect a board of 12 directors and a president. Until that moment, only one other bank, Philadelphia’s Bank of North America, had existed in the new United States.1

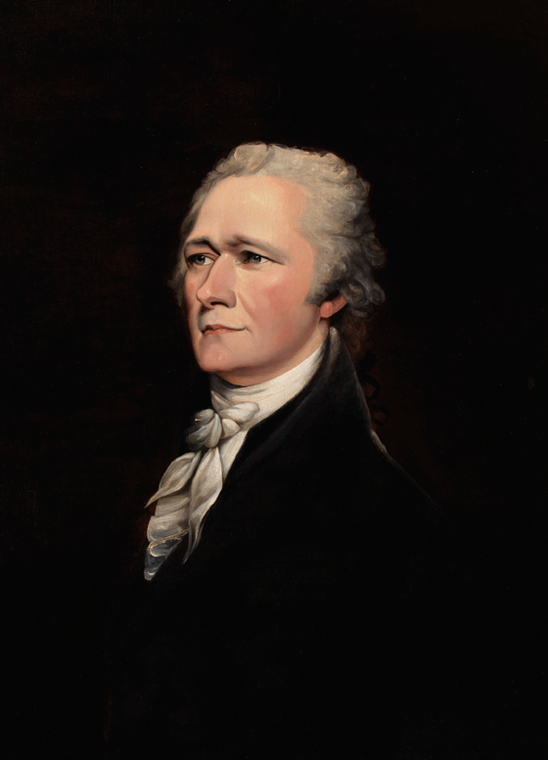

Surveying the meeting, a knowledgeable observer would have noted the group’s shared interest in the city’s commercial economy, but also their diverse backgrounds. Most of them, like Samuel Franklin and Nicholas Low, were established merchants, long accustomed to shipping cargoes across the Atlantic and the Caribbean to and from East River wharves. But their numbers also included Alexander McDougall, son of a dairy farmer, who had become a seaman at age 14 and a ship captain, privateer, and trader thereafter. Some of the subscribers were native-born New Yorkers, like Isaac Roosevelt and Comfort Sands, men of Dutch and English ancestry, but others were immigrants. One of the latter, a young Caribbean-born attorney named Alexander Hamilton, had become a prime mover and the most active organizer in the efforts to found the bank.

Most strikingly, the individuals converging on the coffee house that morning represented opposing sides in the revolutionary struggle that had divided New Yorkers over eight bitter years. Only three months earlier, General George Washington and the Continental Army had marched triumphantly into the city, ending a seven-year British occupation and concluding the War of Independence. Now, former loyalists such as Joshua Waddington and William Seton were creating the bank with ardent revolutionaries like McDougall and Hamilton, both of whom had served as officers under Washington. Soon, banks would become a focal point for anger and political controversy in New York and throughout the nation. But for the moment, the new institution represented only economic ambition and growth.

John Trumbull,

Alexander Hamilton, ca. 1804.

Oil on canvas (30 × 25 in).

Museum of the City of New York,

Gift of Mrs. Alexander Hamilton and General Pierpont Morgan Hamilton, 71.31.3

Wallet, 1787. Leather.

Museum of the City of New York, 56.68.2

Lacking a standardized currency, 18th-century Americans walked around with various kinds of money in their pockets and wallets. This wallet belonged to George Henry Remsen (1768–1804), a member of one of New York’s oldest merchant families. Remsen probably used it to carry a variety of bank notes and promissory notes.

What united these New Yorkers was a common desire to use finance to energize the city’s commercial economy and their own profit-making endeavors in a new postwar era. The buying and selling of merchandise had always been the lifeblood of the town established as a commercial enterprise by the Dutch West India Company in 1624 at the tip of Manhattan Island. The export of furs, grain, flour, lumber, and other American raw materials in exchange for imported cargoes—European textiles, tableware, and hardware; West Indian sugar and rum; enslaved Africans—had long animated the East River waterfront and pumped money throughout the city’s economy, from merchants to the sailors, shipwrights, lawyers, artisans, servants, day laborers, drivers, and shopkeepers they employed or did business with.

Yet New Yorkers rarely had enough metal currency in hand to settle all their payments with their suppliers, creditors, and dependents. Colonists used an array of foreign coins from intercolonial and overseas trade, as well as privately issued IOUs—bills of exchange and promissory notes—to make up the balances they owed to other colonists and to merchants across the Atlantic and Caribbean. Although British regulations, including the Currency Act of 1764, prohibited colonists from founding banks or creating paper currency, most colonies did issue paper bills in an effort to provide a stable and ample circulating money supply. The English colony of New York had created “land banks” in 1737 and 1771—offering government-sponsored loans of paper bills, secured by the real estate of borrowers—in order to provide a source of liquidity for colonists and revenue for the government in the form of the interest payments. During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress and the revolutionary states, including New York, also issued currency to pay wartime expenses, much of which notoriously depreciated in value.

The end of the war confronted New Yorkers with unprecedented opportunities and challenges. The city was now the capital of New York State (1784), and it would soon become the nation’s capital (1785). But New York was also still reeling from the traumas of the British occupation years: runaway inflation, devastating fires that destroyed hundreds of buildings, and recurrent influxes and out-migrations of war refugees. The thousands of redcoats and loyalists who had recently left the city took most of the specie supply—the gold and silver coins that formed the basis of trade—with them into exile. Yet New York entrepreneurs were already seeking to revive the city’s maritime trade and find new markets: in February 1784, investors, including bank supporter Isaac Sears, had sent forth the Empress of China, a ship laden with 30 tons of medicinal ginseng root from the American interior, bound for Canton, to seek a return cargo of chinaware and tea. In the same spirit, the bank’s promoters hoped the new institution would stimulate confidence and economic growth as Manhattan assumed its place among the new republic’s leading seaports. Wherever banks were established, Hamilton later explained to George Washington, “they have given a new spring to agriculture, manufactures, and commerce.”2

The Bank of New-York

The Bank of New-York opened in June 1784 in a converted mansion, the Walton House, on what is now Pearl Street near Frankfort Street, with McDougall as president and Hamilton as a director; in 1787 it would move to Hanover Square, also close to the East River docks. Its initial capital stock, paid in by its shareholders, was $500,000 in gold and silver. In addition to a cashier, by 1786 it employed a teller, an accountant, a receiver of money, a runner, a clerk of discounts (loans), and a porter. Like the English and European commercial banks on which it was modeled, this New York bank would be an institution of “deposit and discount,” taking in the investments of shareholders and the deposits of merchants and others, and using those funds to lend to merchants and other borrowers willing to pay interest. This accumulating interest would become profits accruing to the accounts of the bank’s owners. By pooling investment capital, they would serve themselves as well as the city’s broader economy: many, if not most of the early borrowers were also shareholders, making the bank a fairly exclusive club. By 1791 the bank had 192 shareholders, most of them leading male merchants and lawyers, although 10 women also held bank stock.

Credit—the lending of money for profit—had long been the lubricant of New York trade. The city’s (and nation’s) existing money supply, an odd assortment of foreign coins and paper bills of credit issued as loans and payments by colonial and state governments, had never been sufficient to pay for the cargoes that merchants imported from Britain and elsewhere. As in the colonial era, New York merchants continued to rely on private networks of credit and debt. Importers, usually charging an interest fee for the privilege, allowed the shopkeepers who bought their goods to delay payment until after they had sold the merchandise to consumers for cash. This process might take months as American farmers planted, harvested, and sold their crops for spending money or local store credit. Such chains of credit often stretched from European or Caribbean export merchants to New York importers, from them to local wholesalers and retailers, and finally to the country storekeepers who sold the imported tools, cloth, dishes, sugar, tea, and coffee to farmers and villagers—the final buyers.

“Can” decorated with American man-of-war, 1800–1815. Porcelain.

Museum of the City of New York,

Gift of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 36.18.8

By the 1810s about 15 New York ships voyaged to China each year, bringing back tea, spices, and porcelain. This Chinese export “can” (or mug) would have been used for beer, ale, or cider.

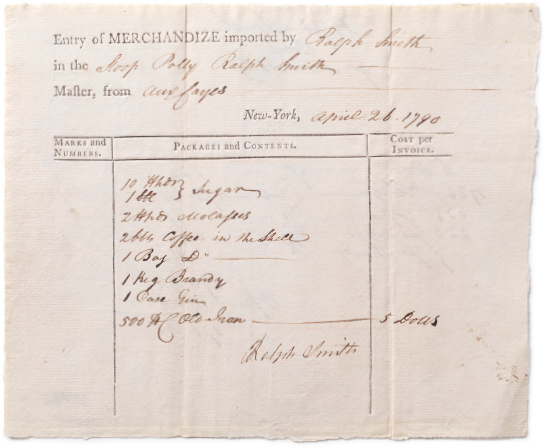

U. S. Customs slip for imported Haitian goods, New York, April 1790.

U.S. Customs

Alexander Hamilton’s federal customs service brought revenues into the U.S. Treasury through duties collected on goods landing at New York and other seaports.

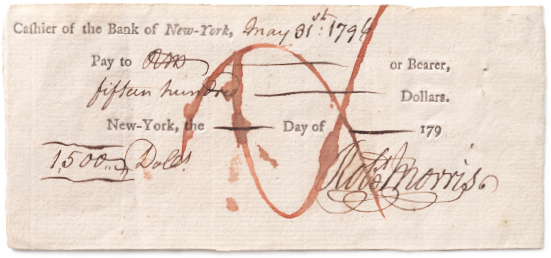

Bank of New-York check, May 31, 1796.

Collection of BNY Mellon

Although bank checks could be used as a form of payment, they were no substitute for hard money (gold or silver) and did not insulate users from risk. As with bank notes, which would proliferate in the coming decades, the worth of a check depended on the credibility of the person distributing it. This check was written by Robert Morris (1734–1806), a financier of the Revolution, who later borrowed money to buy land in the West and South—money he was unable to pay back. People were thus loath to accept his bank checks, as he was overextended and being sued for nonpayment. Morris wrote this $1,500 check, payable to himself or to whoever presented it at the Bank of New-York’s office, during an urgent moment when he needed cash and was trying to sell large property holdings in the District of Columbia. The “x” in the center of the check is a cancellation mark. Morris eventually landed in debtors’ prison.

The Bank of New-York now performed a vital service of lending money in exchange for interest, “discounting” the IOUs of Manhattan merchants and shopkeepers. For example, a Pearl Street shopkeeper could draw up an IOU (called a promissory note), pledging to pay the Bank of New-York $100 in 90 days. If a committee of the bank’s directors deemed the note to be valid and collectible, cashier William Seton would give him the amount of the note in specie or account credit, minus a “discount” or up-front interest charge. At 7 percent per annum, the maximum legal interest fee in New York State, the discount would be $1.75 for 90 days, and the shopkeeper would walk out of the bank with $98.25 in gold or silver coins, or else have that amount credited to a bank deposit account he had opened. With the money in hand, the shopkeeper now could pay the latest invoice from the Front Street importer he bought goods from, buy new merchandise, or pay other expenses. When the debt came due in 90 days, the bank would collect the full amount of $100 from the shopkeeper, thereby earning as profit the $1.75 it had discounted three months earlier.

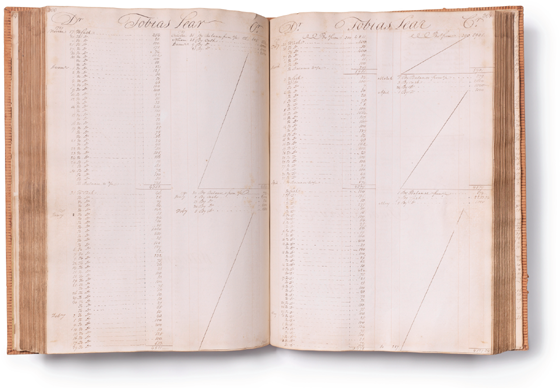

Bank of New-York ledger, 1789–90.

Collection of BNY Mellon

This ledger records transactions made by Bank of New-York clients during the time that New York served as the nation’s first federal capital, from March 1789 to July 1790. Included are the accounts of Alexander Hamilton and most members of the first cabinet (although not Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who kept his accounts in Virginia), many members of Congress, and Vice President John Adams. President George Washington’s own account is not listed by name, but was probably administered by his aide Tobias Lear, whose page is displayed here.

Such discounting brought profits to the bank’s shareholders in the form of interest fees collected up front, while easing transactions and accelerating the speed at which the city’s merchants could get ready money to pay their own debts and invest in new commercial endeavors. By the spring of 1785, the bank had already discounted $1.3 million in notes. As one of the bank’s early newspaper ads asserted, its existence “surprisingly augments the force of doing more business in less time and with greater facility to all parties.” This financial liquidity would enable the city’s economy, and its global commercial ties, to grow more quickly.3

The Bank of New-York provided other services as well. It “accommodated” merchants by renewing their loans over time in exchange for additional interest payments. It offered depositors a safe place to keep their business funds, and they could write checks and drafts on their bank accounts to pay creditors. After becoming President Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury in 1789, Hamilton requested that the bank offer its services to the new federal government headquartered in New York City. Hamilton arranged a $50,000 loan to the government, and the bank also came to hold the accounts of most cabinet members, many congressmen, Vice President John Adams, and probably Washington (under the signature of his aide Tobias Lear). In 1794, Hamilton also arranged a $300,000 loan to the government to help fund one of his pet projects, the Society for Useful Manufactures, which sought to turn the village of Paterson, New Jersey, into a planned industrial community. Hamilton thus embedded the bank in his plans for a federal union that promoted commerce and industry, a vision in which cities like New York and their financial resources were the engines. He saw no conflict of interest in a new economy where, he believed, public and private sources of wealth would together foster prosperity and national greatness.

Most critically for New Yorkers outside the exclusive circles of shareholders and depositors, the Bank of New-York and the other commercial banks that followed it issued loans and payments in the form of “bank notes,” backed by the gold and silver coins they held. The U.S. Constitution prohibited the states from directly issuing coins or paper money. But state governments, including New York’s, permitted private banks within state boundaries to issue paper notes, which could be redeemed (exchanged) at the bank for the equivalent value in specie. Supplementing coins and IOUs in circulation, this supply of paper money flowed through the economy, augmenting barter, payment in kind, and other cumbersome and slow forms of payment. Like the merchants’ discounts, bank notes brought ease, speed, and liquidity to the transactions of the broader population both in the city and beyond. As an observer noted of New York City banks in 1818, “large quantities of their paper were always in the hands of the community, and remained for long periods in remote districts of the state.” As banks sprouted up in Manhattan, Albany, Philadelphia, Boston, Salem, Baltimore, and elsewhere, New Yorkers and other Americans increasingly used this paper money, issued by numerous banks in a bewildering variety of shapes, sizes, and designs, when they bought goods and services or received their pay.4

Colony of New York Five-Pound Note, 1776.

Museum of the City of New York, 33.213.7C

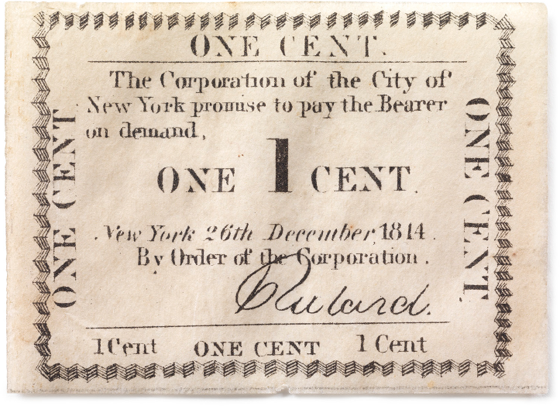

Corporation of the City of New York One-Cent Note, 1814.

Museum of the City of New York, F2012.18.62

New Yorkers were familiar with paper money before the founding of the Bank of New-York in 1784. In the early republic, the issuing of paper money would become the province of private, state-chartered banks such as the Bank of New-York. City governments and even private businesses also issued notes in payment to employees or vendors.

The Bank of the United States

The second bank to open in the city, the New York branch of the Bank of the United States (1792), would be a source of controversy from its inception, galvanizing strongly held feelings about the hazards of banks and financial markets. The Bank of the United States, proposed by Secretary Hamilton in 1790 and enacted by Congress in 1791, was chartered for 20 years and headquartered in Philadelphia, which had replaced New York as national capital in 1790. But the bank’s New York branch became a symbol for many of the thin line separating economic growth from what they viewed as immoral avarice and financial catastrophe.

Hamilton saw this new institution as a central bank for the entire nation, modeled primarily on the Bank of England (1694). Though defined as a mostly private entity, it was intended to perform important public functions. The bank would serve as a depository for collected federal taxes and would be able to make loans to the government, funded by the sale of 80 percent of its stock to private investors and the remaining 20 percent to the government. Private borrowers could go to the bank for loans, thus stimulating American business, while its bank notes would provide a reliable and uniform currency (even as other banks issued their own competing notes). Bank stock would help tie affluent investors to the federal government and to a vision of national economic growth. By offering competitive interest rates and U.S. government backing, the stock would also attract European investors and draw their capital to help build the American economy.

The main branch of the Bank of the United States first offered shares for public sale in July 1791 and then opened on Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street five months later; the New York branch opened its doors on Pearl Street in April 1792. In both cities, however, the bank triggered manic speculation. Convinced that government-backed bank stock would soar in value, many New Yorkers feverishly bought and sold shares as quickly as they were offered. The Merchant’s Coffee House, where most of the stocks were auctioned, became the scene of daily bidding frenzies and rumor mongering by dealers seeking to manipulate the going price. Because Hamilton wanted the bank to be a presence throughout the economy, shares were initially offered in the form of scrip that allowed buyers to put down a small fee and then pay off the balance over 18 months; this permitted less affluent purchasers to dabble in the emerging securities market in the hope of making large profits. One alarmed observer claimed to see “mechanics deserting their shops, shopkeepers sending their goods to auction, and not a few of our merchants neglecting the regular and profitable commerce of the City” as they traded scrip and bank shares.8

The second bank to open in the city … would be a source of controversy from its inception, galvanizing strongly held feelings about the hazards of banks and financial markets.

Jacob Barker, Private Banker

“I have been denominated a mysterious man”

Audacious, politically savvy, and adept at putting himself at the center of the action, Jacob Barker (1779–1871) foreshadowed both the self-confidence and the risk-taking of many New York bankers who followed him. If Alexander Hamilton represented the sober face of early New York banking, Barker—part man on the make, part showman—symbolized its flamboyant side. “I have been denominated a mysterious man, the most mysterious man of the age,” he boasted in 1827. Born in Maine and raised on Nantucket, Barker moved to New York City about 1797 and became a successful merchant in trade with Russia. Without founding a formal bank to pool the capital of shareholders, he began operating as a private banker, lending money to various individuals and enterprises. The city’s merchants had long functioned as financiers for each other, extending interest-bearing credit and insurance, but Barker’s endeavors represented a new scale and degree of specialization, tailored to both the city’s and the nation’s emerging financial needs.5

By 1813, Barker had become a player in Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin’s efforts to sell federal bonds to pay for the War of 1812. As middleman between the Department of the Treasury and wholesale investors in New York, Barker hoped to earn profits on the discount price the government extended to him, but he later claimed the Treasury had reneged and deprived him of the revenues he deserved for selling $5 million in bonds. In 1815 he founded the private, nonchartered Exchange Bank to aid “small traders” and artisans who, like him, were Democratic-Republicans allied with Tammany Hall. But the bank failed in 1819, and in 1827, he was found guilty of conspiracy to defraud several New York insurance companies and banks. Barker vehemently protested that the charges were trumped up by his enemies among “the monied aristocracy of Wall-street.” Despite the convictions, Barker stayed out of jail and survived as a merchant in the Russian trade before moving to New Orleans in 1834.6

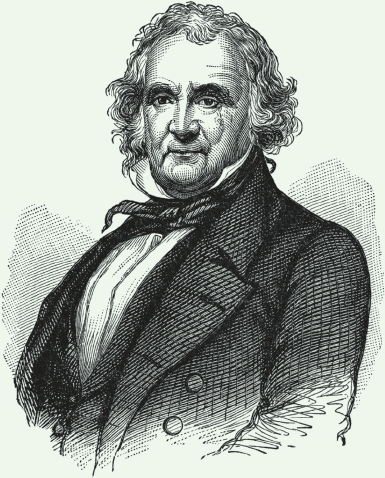

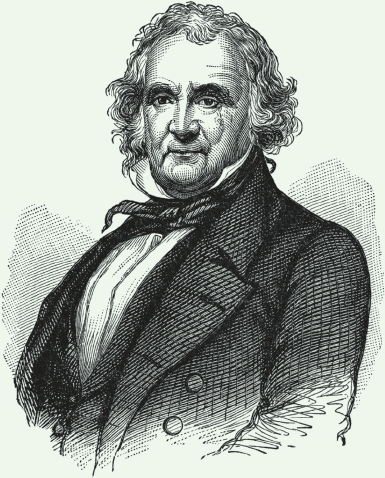

Jacob Barker, from Harper’s Encyclopedia of United States History.

(vol. 1), ed. John Benson Lossing (Harper and Brothers, 1912)

Barker was an enthusiastic creator of his own legend. Thanks to his wartime bond sales, he claimed to be “the pivot on which this important nation rested at one of the most important periods of its history.” Freely conceding his own vanity, Barker came close to admitting that he availed himself of the “inordinate appetites for gain” of Americans in a new, free-wheeling economy of bank shares, corporate stocks and bonds, and paper money.7

Barker’s career also presaged the emergence of private bankers as a force to be reckoned with in New York’s financial world. By the 1820s, players like Nathaniel Prime of the firm Prime, Ward & King were selling Erie Canal and state bonds to English and European investors. By purchasing large blocks of stocks and bonds issued by promoters of states, cities, canals, and early railroads, then selling them to American and European investors, these men pioneered what would later be called investment banking. In Barker’s footsteps, they made nineteenth-century Wall Street the focal point of transatlantic finance and maintained Britain as the major source of capital for the New York financial markets.

—Steven H. Jaffe

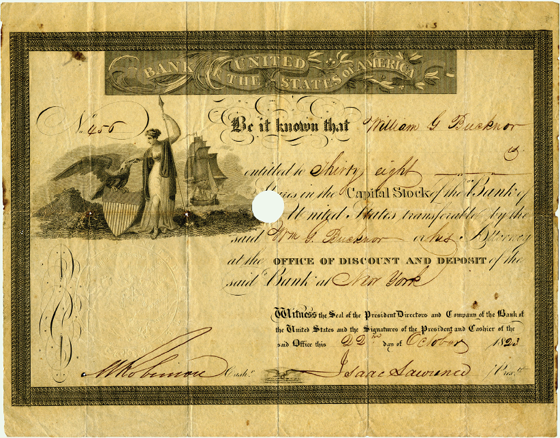

Stock certificate for Bank of the United States, 1823.

Collection of Mark D. Tomasko

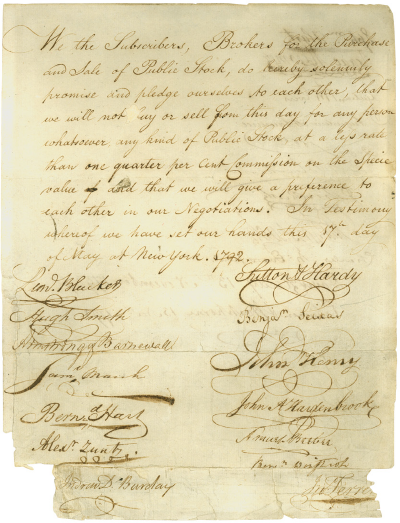

“Buttonwood Agreement,” 1792.

New York Stock Exchange Archives, NYSE Euronext

The Panic of 1792 became New York’s—and the nation’s—first great financial crisis. In March of that year, the price of government bonds and bank shares peaked and then rapidly plunged as worried investors, fearing that the speculative market was collapsing, tried to sell their securities. By flooding the market with shares and anxiety, they produced the very price collapse they feared and ruined many who had gambled on a continuing rise. The most conspicuous speculator, New Yorker (and former assistant secretary of the treasury) William Duer, who had borrowed heavily to pay for his investments, ruined himself and numerous creditors after securities prices plummeted in March. Duer landed in the city’s Debtor’s Jail; some furious New Yorkers besieged the jail in an effort to get at him.

In the panic’s wake, 24 securities brokers signed a compact pledging to trade only with one another rather than to the public, shunning the auction system that had helped to trigger the mania. Known as the Buttonwood Agreement, after the buttonwood tree on Wall Street under which the brokers traded in fair weather, the pact that the board of brokers signed established the association that became the direct ancestor of the New York Stock Exchange. The agreement bore witness to the fact that New York banks and securities markets were intertwined. The crisis that brought it into being also taught New Yorkers that banks, intended as a source of growth and stability, might also become direct or indirect causes of instability.

Although the panic passed and New York’s branch of the Bank of the United States did not even open until the worst of the crisis was over, the episode fostered anger and confirmed old suspicions. In the largely rural and agricultural world of postrevolutionary America, the urban merchants who needed bank discounts for long-distance trade were a small minority of the population. In Europe, usury, defined as the lending of money at excessively high interest rates, had often been outlawed as sinful and un-Christian. The stigma of the usurer had stuck to those traders, often members of mistrusted minorities like Jews or Lombards (Northern Italians active in England and France), who had been legally allowed to lend money in European countries, and Americans inherited that mistrust. Some knew that banking dynasties like the Medici and the Fuggers, as well as the Bank of England, had helped to build the modern European nation-state, but precisely because they possessed such power, many feared that banks and the elites served by them would be able to override the people’s liberties.

Francis Guy, Tontine Coffee House, N.Y.C., ca. 1797. Oil on linen (43 × 65 in).

Collection of The New-York Historical Society

Francis Guy depicted the intersection of Wall and Water Streets in the era when the district was becoming the seat of New York’s emerging financial district. At far right is the corner of the Merchant’s Coffee House, site of the founding of the Bank of New-York in 1784 and of heated share trading during the Panic of 1792. At far left, under the American flag, is the façade of the Tontine Coffee House, opened in 1793.

Above all, numerous Americans now feared that a small circle of wealthy and influential men—Hamilton and his allies—might use bank capital to buy influence, corrupt government, and subvert the republic. Several of the founding fathers felt this way about banks in general. “An aristocracy of bank paper is as bad as the nobility of France or England,” wrote John Adams, who classified bankers as “swindlers and thieves” (even though he opened an account at the Bank of New-York). Thomas Jefferson, who blamed Hamilton’s bank scrip for triggering “the rage of getting rich in one day,” agreed; to him, a banking system was “an infinity of successive felonious larcenies.” As Benjamin Rush saw it, “private credit and loan offices … [beget] debt, extravagance, vice, and bankruptcy.” Heated disagreements between champions and foes of banking would shape the nation’s political future.9

Indeed, by the mid-1790s, in New York and throughout the country, the controversy over banks was helping to spur the rise of the first national party system, pitting Hamilton’s Federalists against the Democratic-Republicans of Jefferson and James Madison. These political fault lines would soon prompt the founding of New York City’s third bank, the Bank of the Manhattan Company.

The Manhattan Company

In 1799, a seemingly innocuous petition worked its way through the New York State legislature in Albany. Sponsored by a bipartisan group of civic leaders, including Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, the petition asked the state to charter a private entity, to be known as the Manhattan Company, to provide the city with fresh water. Yellow fever epidemics had alarmed New Yorkers about the unhealthiness of their well water, and the petitioners proposed to pipe water into the city from the Bronx River. Unlike general incorporation laws today, each charter was an individual law incorporating a specific business enterprise; like other state ordinances, it had to be passed by the legislature and signed by the governor. Securing a corporate charter was important, because it entitled an incorporated private enterprise like a water company or a bank to a set of legal privileges granted by the state, including the protection of limited liability for its investors. This meant that if the company incurred debts, its shareholders could only lose the money they had already invested in the concern, and could not be sued for any remaining debt over and above their investment—an important protection in an era when insolvent debtors were routinely thrown into prison. But obtaining a charter was also challenging, since legislators consulted their own political and financial interests in voting for or against any given act of incorporation. Indeed, many Americans viewed corporate charters much as they viewed banks: as entities of special privilege that served and enriched elite insiders while keeping the common people from sharing their benefits. The Bank of New-York did not obtain its charter until 1791, seven years after its founding, largely because upstate lawmakers opposed chartering a bank that would serve New York City interests rather than their rural constituents.

Burr, a leading Democratic-Republican politician and a shrewd opportunist, managed to line up the votes in Albany for chartering the water company. But as the vote drew near, he also inserted an extra clause into the act’s final draft, enabling the Manhattan Company to use its surplus capital in “monied transactions or operations.” Federalist assemblymen and state senators overlooked or ignored the clause as they voted the charter into law. Only later did Federalists, including Hamilton, realize that Burr’s “Politico-Commercial-Financial-Bronx-Operation” had enabled Hamilton’s Democratic-Republican political rivals to establish their own bank.10

The Bank of the Manhattan Company, which opened at 23 (later 40) Wall Street in late 1799, became a base for organizing and sponsoring Democratic-Republican Party activities in New York City. Jeffersonians in New York had long complained that the city’s two existing banks were dominated by Hamilton’s Federalists, who loaned to their political supporters and discriminated against Democratic-Republican merchants. Although the charge was exaggerated (the Bank of New-York did lend to some Jeffersonians), Burr’s party now possessed a bank of its own. The Manhattan Company’s directors, although not exclusively Jeffersonian, included men who helped elect Thomas Jefferson president by canvassing and getting out the Manhattan vote in 1800. The bank’s existence also affirmed the rise of an urban, commercial variety of Jeffersonian republicanism which, rather than looking askance at banks, used them to make loans to politically friendly merchants and artisans. “The cause of republicanism … is intimately connected with the prosperity of our institution,” Democratic-Republican De Witt Clinton wrote to the bank’s cashier in 1808. Like the Bank of New-York, the Manhattan Company also attracted female investors, presumably including members of families active in Jeffersonian politics; of the company’s first 388 shareholders, some 53 were women.11

The Manhattan Company’s founding also held other implications for New York banking. The charter established a tradition that connected banks directly to urban development, even though the firm’s water supply system—which ultimately used Lower Manhattan’s Collect Pond, a Chambers Street reservoir, and wooden pipes laid beneath the streets rather than the Bronx River—never proved adequate for the growing city’s needs. And although Burr did nothing illegal by inserting his clause, his subterfuge coincided with the onset of an era in which the chartering of new banks often became a matter of bankers bribing the right legislators in Albany. The 19th century, with new opportunities and risks, was at hand.

“He has lately by a trick established a Bank—a perfect monster in its principles, but a very convenient instrument of profit and influence.”

Hamilton on Burr, 1801

The Demise of the Bank of the United States

In 1811, an event occurred with major consequences for banking in New York City: a Democratic-Republican Congress in Washington refused to renew the charter of the Bank of the United States (BUS). Despite its association with the Panic of 1792 and Jeffersonian fears of its power, the bank had played a mostly stabilizing role in the American economy, using its lending policies and transactions with private banks to force them to honor their commitment to redeeming their own bank notes in specie. By agreeing to accept the notes of state-chartered banks in payments and exchanges, the Bank of the United States had been able to unload these notes on the issuing banks when its authorities believed they were triggering economically harmful inflation by circulating too many notes. Demanding payment in specie for the bank notes it had collected, the BUS drained gold and silver from the “reckless” institutions, thereby reducing their specie holdings and thus their basis for issuing new notes. The threat of being targeted in this way deterred banks from inflating the money supply with their loans and bank notes.

In the vacuum that followed the Bank of the United States’ demise, the New York State legislature chartered several new private banks in Manhattan. These included the Bank of America (dominated by Federalists), the City Bank of New York (Democratic-Republican), and the Mechanics’ Bank (to supply capital to master artisans). As their promoters and shareholders had hoped, some of these banks, including the City Bank, eventually became official local depositories of the federal funds that Congress removed from the Bank of the United States, further bolstering New York’s role as a national financial center. But the city had not yet attained the primacy it would later enjoy. In 1815, Manhattan possessed eight commercial banks, but so did Philadelphia, the acknowledged financial leader; meanwhile, Boston and the District of Columbia each had seven, and Baltimore had nine.

There was another, unintended result of the death of the national bank in 1811. When the United States declared war on Great Britain in 1812, the federal government lacked a central bank to help it mobilize the nation’s financial resources to pay troops, buy provisions, and borrow money from the American public. Into the gap stepped a group of savvy businessmen based in New York City and Philadelphia, eager to help the nation win the war, for a price. The German-born merchant John Jacob Astor, already making a fortune in the China trade and in Manhattan real estate deals, became a key New York player; so did a shrewd trader named Jacob Barker. Along with Philadelphia’s Stephen Girard and David Parish, these men became, in essence, private bankers to the U.S. government; the “loan contracting” they undertook for the Madison administration—buying massive blocks of federal war bonds at a discount on behalf of syndicates of investors and then selling them at a profit to retail dealers, investors, and commercial lenders such as the City Bank—foreshadowed the investment banking of a future generation. By the end of the war, Astor, Girard, and others had raised millions of dollars to help the U.S. government fight and survive the War of 1812, while profiting handsomely themselves. The transactions clinched Astor’s connection to the City Bank, which would one day become the nation’s largest bank. They also established a precedent for Wall Street to bankroll America’s future wars.

Section of water supply pipe installed by the Manhattan Company, ca. 1799. Varnished wood with copper plates.

Museum of the City of New York, 94.62

Although the Manhattan Company used the vast majority of its two million dollars’ worth of funding for banking rather than water, it did dig wells and lay pipe to supply water in Lower Manhattan. This section of pipe was excavated in 1961 during water main construction at the intersection of Fulton and Pearl Streets.

An Era of Growth

After the War of 1812, New York entered an era of uninterrupted growth. By 1820, New York’s population of 122,000, swelled by renewed transatlantic immigration, made it North America’s largest city and leading seaport. By 1825, entrepreneurs had established packet lines that linked New York to Liverpool, London, and Le Havre on a regular schedule, and they had come to dominate the financing of the South’s cotton export trade. The city’s commercial banks played a role in each of these developments, discounting merchants’ notes, putting dividends in the accounts of shareholders who invested them in trade, and renewing loans for businessmen engaged in long-distance commerce.

Those banks, moreover, were helping to turn Wall Street into the city’s financial center. In 1793 the new Tontine Coffee House at the corner of Wall and Water Streets had replaced the Merchant’s Coffee House as the city’s mercantile exchange and the site where brokers traded bank and government paper. The Bank of New-York settled into the city’s first purpose-built bank edifice at 48 Wall Street in 1798, as insurance companies, brokerages, and other banks moved into converted Georgian and Federal storefronts and houses nearby. By the late 1820s, 10 of Manhattan’s 16 banks were located on the street. Most of them functioned in one or two rooms, where directors gathered to vote on whether to issue discounts to applicants and to conduct other bank business. Paid cashiers, clerks, and bookkeepers assisted. In a world without electronic communications, the daily face-to-face exchange of information along a few blocks of Wall Street ensured that geographical clustering would continue as New York City became ever more clearly the nation’s trading and banking capital.

John Wesley Jarvis, Philip J. Hone, ca. 1810. Oil on wood panel. (30 × 24½ in).

Museum of the City of New York,

Gift of Henry W. Munroe, 85.205.1

Merchants were the key players in New York’s early 19th-century banking. Indeed, most “bankers” were primarily merchants who spent a few hours each week reviewing discounts in the bank office and the rest of their time overseeing their own businesses and engaging in a wide range of civic activities. Only gradually did the work of the bank’s cashier, bookkeeper, and clerks become recognized as full-time careers. Even men who, by mid-century, had become specialists in banking were usually veterans of the city’s booming overseas and coastal trade. Philip Hone, for example, had become wealthy as an auctioneer selling imported British goods to Manhattan wholesalers; by the time he was president of both the American Exchange Bank and the Bank for Savings in the 1840s, he had also been the city’s mayor, a backer of a successful canal linking Pennsylvania coal fields to the Hudson River, a trustee of three insurance companies, and a noted philanthropist. City Bank board member Benjamin Marshall, an English Quaker immigrant, was an exporter of Georgia cotton and an importer of English cotton textiles, as well as a founder of the Black Ball Line of packet ships shuttling between Manhattan and Liverpool. For these men, using banks to lend and borrow money (and to diversify their assets) was a natural by-product of their role as “merchant princes” who regularly needed capital to keep cargo ships plying between New York and Liverpool, Hamburg, Charleston, Mobile, Havana, Batavia, Canton, and other ports.

The Bank for Savings

In 1819, a group of New Yorkers opened a new kind of bank that would play a pivotal but often overlooked role in American history. Their Bank for Savings in the City of New York was intended “to induce habits of economy by receiving the savings of laborers & domestics & putting them out to interest.” The founders, a circle of businessmen-reformers including John Pintard and Thomas Eddy, were riding the wave of religious fervor known as the Second Great Awakening. As Quakers and evangelical Protestants, these prosperous men believed that aiding the poor and steering them clear of sin was a Christian obligation; they also viewed this stewardship as a way to control the social disorder that seemed to be arriving with the onset of industrial wage labor and the influx of immigrants from Ireland, Western Europe, and the American countryside.12

The bank deposited the savings of working-class laborers and servants in accounts earning modest interest accruing from “safe,” presumably low-risk loans the bank’s trustees made on their behalf. Unlike commercial banks, this mutual savings bank—legally owned by the depositors, but managed by volunteer philanthropists—would not discount the IOUs of merchant borrowers, but it would be able to invest deposits in interest-bearing federal and New York State bonds. Working people would learn the value of thrift, accumulation, and the delayed gratification that came from putting wages into savings rather than squandering them on alcohol and luxuries the poor supposedly could not afford. Although many early depositors turned out to be affluent parents opening accounts in order to teach thrift to their children, thousands of laborers flocked to the bank to receive their personal passbooks and deposit whatever savings they could eke out of their pay. So did thousands of single and married women; by 1857, the majority of Bank for Savings accounts belonged to women.

Anthony Imbert, Erie Canal Celebration, New York, 1825. Oil on canvas (24 × 45 in).

Museum of the City of New York, 49.415.1

On November 4, 1825, nearly 20,000 visitors flooded into Manhattan to celebrate the completion of the Erie Canal. New York City’s Bank for Savings proved critical to early financial support for the canal, built at a cost of $7 million by New York State.

The Bank for Savings introduced many working people and immigrants to entirely new ways of thinking about money and savings. Along with traditional artisans, men and women from agricultural communities in rural America and Europe came to New York with traditions of sharing economic resources in which the notion of earning interest did not exist. Kin and friends made free loans to each other or “treated” each other to food and drink, assuming that the borrower in turn would lend to or “treat” them without charge if the need arose. New organizations such as artisan benevolent societies and early labor unions also provided mutual aid to workers in return for their membership fees and dues.

By the 1820s, however, working people in New York were becoming increasingly enmeshed in the booming market economy, and the Bank for Savings integrated them even more fully into the urban commercial world. Teaching the working poor to save and earn interest was a key goal of the bank’s founders. So was detaching the poor from emerging working-class neighborhood institutions like saloons, where alcohol and “treating” were intertwined, and from the pawnshops of Chatham Street, where “Shylocks” charged high (and often illegal) interest rates for lending money to people who brought household items as collateral, as well as fencing stolen goods. Bank for Savings founders aimed at nothing less than transforming the moral character and daily behavior of the poor by teaching them the middle-class values of frugality, temperance, self-control, profit, and individual acquisitiveness. Each generation of immigrants to follow would grapple with learning these new “American” ways, often in part through the opening of savings accounts.

Other savings banks followed. By 1860, there were 18 mutual savings banks in New York City and five more in Brooklyn and Queens, catering to specific neighborhoods, Irish and German immigrant communities, and occupational groups including seamen, dock workers, and merchants’ clerks. By 1855, almost two-thirds of adult New Yorkers, nearly 250,000 people, held savings accounts. Five years later, the two largest institutions, the Bowery Savings Bank and the Bank for Savings, each had over $10 million in deposits and were ranked among the nation’s 10 largest businesses.

By 1855, almost two-thirds of adult New Yorkers, nearly 250,000 people, held savings accounts.

The Bank for Savings quickly came to play a role that far transcended its philanthropic origins and the geographical limits of its original basement office in the city’s almshouse in City Hall Park. As businessmen, Pintard, Eddy, and other bank trustees had long been advocates of plans for a “Grand Canal” linking the city to the frontier of the Great Lakes region. Having gained Governor De Witt Clinton as their most influential ally, they became the Erie Canal’s crucial financial backers when the state began to sell bonds to pay for the canal’s construction in 1819. By 1821, over $500,000 in deposits by New York City residents was invested in almost a third of the canal’s total debt. By becoming the canal’s largest and most reliable source of capital, the bank secured the project’s financial reputation, attracting additional capital from American and European investors and helping to make Wall Street a transatlantic center for the trading of canal paper; shares in state governments, insurance companies, and banks; and eventually railroad stocks.

Completed in 1825, the canal played an incalculably vast role in the development of the city and the West, as the flow of Midwestern flour, grain, and lumber down the Hudson and across the oceans attracted ever greater accumulations of people and capital to Manhattan and spurred agricultural and commercial growth in western New York and the Great Lakes states. Meanwhile, the Bank for Savings was also pivotal in the city’s growth, buying up blocks of New York City bonds, including those that enabled the city to build its ambitious Croton water reservoir and piping system in the late 1830s, an improvement that finally brought fresh water to thousands of New Yorkers frustrated by the Manhattan Company’s failure to deliver on its promises. The trustees looked proudly on their bank as an institution that simultaneously encouraged the poor to be thrifty, amplified the wealth and influence of the entire state, and brought water to protect the city’s people against the hazards of disease, dirt, and fire, thereby securing further urban growth.

The Safety Fund

By the late 1820s, the reach of the city’s 16 commercial and savings banks could be felt on virtually every cargo ship embarking or arriving at the South Street piers, in the holds of the canal boats and barges pouring down the Hudson River, and in countless daily transactions that increasingly linked Manhattan banks to farms, plantations, general stores, state governments, and other banks across the country. Bankers throughout the Northeast, Midwest, and South had begun to deposit balances in Manhattan banks in order to guarantee that their own bank notes would be redeemed for gold and silver in what was becoming the nation’s commercial metropolis. Such balances also became a liquid reserve, providing these out-of-town banks an efficient means for buying securities on Wall Street and for servicing their own customers by facilitating their transactions with New York City businesses. By 1833, the Mechanics’ Bank at 16 Wall Street held deposits for 45 banks in 14 states. Banks as far away as South Carolina, Ohio, Vermont, and even Canada used New York City banks as depositories; by 1836, Connecticut’s commercial banks had put two-fifths of their total reserve funds—about $1 million—in New York City banks. As a result, Manhattan banks were coming to hold a substantial part of the reserves of the entire country.

Yet banking remained an unpredictable and sometimes risky business in New York, for bankers and everyone else. Panicking New Yorkers stampeded banks during an economic crisis in 1819, much as they had done in 1792. At some banks, directors took advantage of their position by making overgenerous loans to themselves and their friends. Bankers also might print much more paper money than they could redeem in specie, prompting worried depositors and currency holders to drain the banks of gold and silver; this would force the bankers to cease making loans and could trigger economic stagnation and collapse.

To try to stabilize the economy and protect it from such “busts,” the New York State legislature passed the Safety Fund Act in 1829. The brainchild of Joshua Forman, an upstate entrepreneur inspired by what he had read of a similar system among Chinese merchants, the law obligated member banks to pay a yearly percentage of their capital into the fund and sought to regulate the quantity of bank notes and loans they issued. The law also aimed to protect depositors’ accounts, anticipating bank deposit insurance by a century. In return, the banks could draw on the Safety Fund’s specie reserves during financial crises. By guaranteeing a backup supply of liquid capital, the fund promised to take the edge off of panics and prevent currency contractions that might lead to business failures and recession. Although various New York City bankers resented the limitations imposed by the system, it was soon copied by other state governments. The Safety Fund Act contributed to the stability of New York’s banks, further augmenting their increasingly central role in the American economy.

In the four decades that followed the founding of the Bank of New-York in 1784, New York City had gone from a struggling, war-damaged town to, in De Witt Clinton’s words, “the great depot and ware-house of the Western world.” The labor, resources, and mercantile energies of its people had made it the most populous city, the busiest seaport, and the leading immigrant landfall in North America. Encouraged by visionaries like Hamilton, Astor, Barker, and others, New York’s merchants had pooled their capital to found a steadily growing number of commercial banks; poorer New Yorkers put their money into savings banks; and a small number of affluent businessmen pioneered the techniques of private investment banking. In turn, these sources of credit and capital infused the city’s overseas trade, the construction of its vital canal artery to the interior, residential expansion, population growth, and daily work in innumerable direct and indirect ways. Many New Yorkers, like other Americans, continued to fear and resent the power and wealth of banks and bankers and to desire greater popular access to the opportunity and prosperity that bank credit, deposits, and shareholding afforded. Yet few could deny that New York’s primacy as the nation’s Empire City was inextricably linked, as both cause and effect, to its burgeoning banks.13

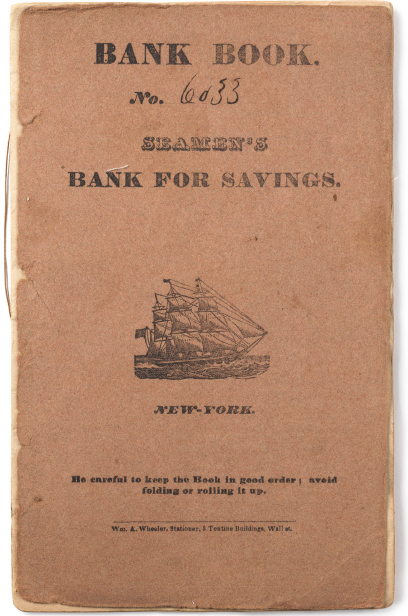

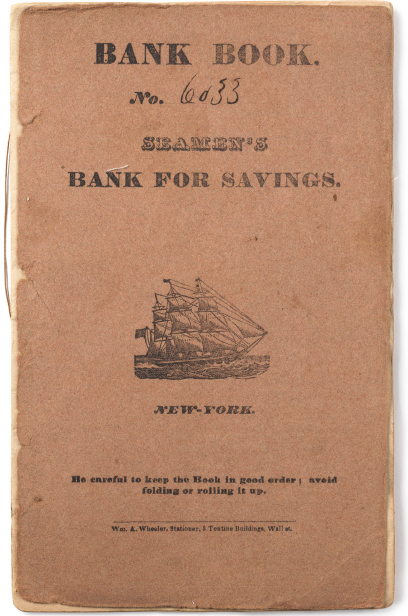

Bank Book No. 6033, Seamen’s Bank for Savings, account of William Rotch, 1834.

Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection, South Street Seaport Museum

The city’s second mutual savings bank, the Seamen’s Bank for Savings (1829), encouraged thrift among sailors, a working-class group viewed as especially “improvident” by wealthy and middle-class philanthropists. The bank also accepted deposits from dockside laborers and their families. This passbook, belonging to account holder William Rotch, records the closing of his account with the payment of $369.55 to Rotch’s estate, presumably following his death—a sizeable amount for a working-class family in 1834.

With the Safety Fund in place and four decades of banking experience behind them, many New Yorkers looked forward to a future in which their financial institutions would play an ever-expanding role at home, across the country, and in trading ports around the world, wherever Americans needed credit to buy and sell goods and make money. No one could foresee that a new decade would put New York’s banks at the center of a nationwide political and economic firestorm.

Endnotes

1 “establish a bank”: Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York: Penguin, 2004), 200. At about the same time in early 1784, Bostonians were founding a third American bank, the Massachusetts Bank.

2 “they have given a new spring”: Chernow, Hamilton, 349.

3 “surprisingly augments”: Robert E. Wright, Origins of Commercial Banking in America, 1750–1800 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001), 99.

4 “large quantities”: Wright, Origins, 114.

5 “I have been denominated”: Jacob Barker, Incidents in the Life of Jacob Barker, of New Orleans, Louisiana; with Historical Facts, His Financial Transactions with the Government, and His Course on Important Political Questions, from 1800 to 1855 (Washington, DC: 1855), 164.

6 “small traders”: Howard B. Rock, ed., The New York City Artisan, 1789–1825: A Documentary History (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 141; “the monied aristocracy”: Barker, Incidents, 158.

7 “the pivot,” “inordinate appetites”: Barker, Incidents, 1, 194.

8 “mechanics deserting”: Chernow, Hamilton, 359.

9 “An aristocracy,” “swindlers,” “the rage,” “an infinity,” “private credit”: Chernow, Hamilton, 303, 346, 361, 387.

10 “monied transactions,” “Politico-Commercial”: Brian Phillips Murphy, “‘A very convenient instrument’: The Manhattan Company, Aaron Burr, and the Election of 1800,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d Series, LXV, no. 2 (April 2008): 246, 255.

11 “The cause”: Murphy, “‘A very convenient instrument,’” 264.

12 “to induce”: Alan L. Olmstead, New York City Mutual Savings Banks, 1819–1861 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 6.

13 “the great depot”: De Witt Clinton, Memorial of the Citizens of New York, in favour of a Canal Navigation between the Great Western Lakes and the Tidewaters of the Hudson, presented to the Assembly, February 21, 1816 (New York: Samuel Wood & Sons, 1816), 7–8.