Erick Locker, Chase Manhattan Bank building (left, detail), ca. 1961.

Ezra Stoller, Manufacturers Trust, 510 Fifth Avenue (detail), 1954.

“DO THEY DO MORE WITH THEIR MONEY THAN YOU DO WITH YOURS?”

a full-page advertisement, placed in Life magazine in 1960 by “The Commercial Banks of the U.S.,” asked readers. The ad featured a photograph showing a suburban homeowner on his front lawn, enviously eyeing his neighbors as they packed their shiny new car for a family vacation. “You’re pretty sure that they don’t make any more money than you do,” the ad intoned, “yet they always seem to be the ones who take the trips … refurnish the living room … buy the new car … build the addition to the house.” The reason the neighbors had more spending money, the accompanying text went on to suggest, was that they used “a full-service commercial Bank.” Such a bank provided the successful family with financial planning as well as savings and checking accounts and an array of loans—personal, car, home, farm, and business. “Perhaps best of all,” the ad stated, “when you work with a full-service bank, you build character, reputation—your ‘standing’ in your community.”1

Sponsored by a trade association of banks, the advertisement evoked familiar themes in post-World War II American culture: the lure of consumer goods as status symbols, anxieties about “keeping up with the Joneses,” the imperative to “fit in” socially. After the deprivation of the depression years and the rationing of World War II, the American economy entered a new boom era in the late 1940s and 1950s, driven by the nation’s role as resurgent industrial producer and dominant superpower; as in the 1920s, being able to afford a plethora of material goods defined American identity and success. In placing the ad, commercial banks reflected the business civilization that defined postwar America. Aside from the San Francisco-based Bank of America, which dominated lending on the booming West Coast, the nation’s largest commercial banks still occupied headquarters on Wall Street or in Midtown Manhattan, not far from the Madison Avenue agencies they hired to create ads for magazines, newspapers, billboards, and by the 1960s, radio and television.

But the advertisement also had an unspoken subtext. Commercial banks needed deposits, the money they lent at interest to borrowers in order to make a profit. Since 1933, however, the banking reform measures of the New Deal had limited what banks could do to attract deposits. The National Banking Act of 1933 (also known as the Glass-Steagall Act), still in effect, prevented banks from offering interest on demand deposits (checking accounts), and the law’s Regulation Q put caps on the interest rates the Federal Reserve System allowed them to offer on time deposits (savings accounts). These measures were intended to restrain banks from engaging in risky investment strategies of the sort they had embraced in the late 1920s. Those strategies had earned money to pay the high interest rates offered to attract depositors, but they had also, regulators argued, helped to bring on the Great Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.

Advertisement from the Commercial Banks of the U.S. in Life, Vol. 49, No. 12, September 19, 1960.

Private collection

In a new postwar era of prosperity and industrial expansion, the government limits frustrated commercial bankers. Prevented from attracting new deposits with beguiling interest rates, banks were thwarted in their ambition to expand loans. In order to raise the capital they needed to make loans following World War II, banks had sold the war bonds and other government securities they had accumulated during the conflict, but they soon depleted this source and faced a shortage of deposits. During the decade of the 1950s, for example, the loans made by National City Bank (and its successor, First National City Bank) more than doubled, but its deposits increased by less than half, preventing further expansion of its business; other banks endured similar disparities. Moreover, as New Yorkers and other American city dwellers adjusted to the material benefits of the “American Century”—a new era of national confidence and world leadership first invoked by Life magazine publisher Henry Luce in 1941—they put their money into an array of financial institutions beyond the purview of commercial banks. So did the increasing numbers of families who took their earnings and savings with them when they moved to new homes in the suburbs and placed their money in savings and loan institutions, credit unions, Treasury bills, mutual funds, or stocks and bonds. Thus the ad was a tactical effort to compete for depositors by offering them the expanded advantages of “full-service” commercial banks in lieu of high interest rates. Even as they pooled their efforts to do battle with other types of financial institutions, however, the big New York commercial banks competed with each other for their own slices of the deposit pie.2

Deck of playing cards advertising Brevoort Savings Bank, ca. 1955.

Museum of the City of New York, 01.52.1A-C

Banks offered novelties, gimmicks, and trinkets to lure consumers in the mid-20th century. These represent the growing concern these institutions had in catching and sustaining the attention of a customer base accustomed to a culture of amusement and disposability. The Brevoort Savings Bank, founded in 1892, was one such institution not above using games of chance to advertise its services.

New York banks took the lead in devising an array of new strategies that sidestepped or compensated for the ongoing government regulations. Advertising, giveaways of toasters and other “freebies” to new customers, financial planning for account holders, and other new tactics and products all sought to hook in customers and their deposits before rival banks or other financial institutions did. Barred from the stock market, commercial banks retooled to expand the consumer side of their business and launched negotiable CDs, one-bank holding companies, money market accounts, and credit cards (see sidebar, page 199), which in turn would help fuel the growth of the consumer economy.

American corporations were also venturing abroad into a world recovering from global war, a world in which Wall Street decisively supplanted the City of London as international lending and financial capital. As foreign governments and entrepreneurs sought American dollars, Wall Street commercial and investment banks loaned and invested abroad; as in the 1920s, New York bankers played a powerful and complex role around the world. The years between the end of World War II and the early 1970s—a time of American prosperity and dominion, the true core of Luce’s American Century—was thus a period of survival and ingenuity for New York bankers. But as the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s, New York banks would also face angry questions and protests over how they shaped the opportunities of ordinary Americans, and over the implications of their presence around the world.

Safe and Sound

In many ways, postwar banks in New York and elsewhere settled into routines that were safe, predictable, even dull, a reflection of the New Deal reforms whose goal had been to take exciting but dangerous risks out of American banking. In retail banking (the over-the-counter business conducted by neighborhood commercial and savings banks with ordinary customers), managers’ discretion was limited. Such banks frequently operated on what was only half-jokingly called the 3-6-3 rule: pay 3 percent interest on deposits, charge borrowers 6 percent for loans, and play golf at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Investment banks faced their own constraints. To be sure, they were still powerful institutions. The four most important—Morgan Stanley, First Boston, Kuhn, Loeb, and Dillon, Read—dominated American investment banking from their Wall Street offices. Morgan Stanley, the investment bank formed in compliance with Glass-Steagall in 1935 when J. P. Morgan and Company opted to become a commercial bank, inherited the House of Morgan’s preeminent investment business. The firm organized massive syndicates, routinely mobilizing as many as 300 underwriters and 800 dealers to issue and sell such securities as $300 million in General Electric bonds in 1953 and $231 million in IBM stock in 1957. But the Securities and Exchange Commission, the government regulatory agency founded during the New Deal, required such banks to file meticulously detailed prospectuses for each security they underwrote, and was tasked with monitoring investment banks vigilantly.

Such scrutiny sometimes produced comic encounters, as well as suggested the continuing social exclusivity of Anglo-Saxon “white shoe” Wall Street firms. One day during the 1950s, SEC regulator Fred Moss arrived at 2 Wall Street, the Morgan Stanley headquarters, to study issues of unusually volatile stock offerings. Moss was greeted by Perry Hall, the managing partner: “My name is Perry Hall—partner, Morgan Stanley, Princeton.” Moss shot back: “My name is Fred Moss—SEC, Brooklyn College. Before my name was Moss it was Moscowitz. And before that it was Morgan, but I changed it in 1933.” Indeed, Morgan Stanley would not have a significant Jewish employee until 1963, when it hired banker Lewis W. Bernard (a Princeton graduate); hiring African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, or women as bankers would remain unthinkable for New York investment banks until the late 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s. Old conventions and biases died hard.3

Wall Street banks clung to other traditions as well. As late as the 1950s, Morgan Stanley entrusted its bookkeeping to clerks who sat on high stools jotting numbers in leather-bound ledgers, much as they would have done a century earlier. But as bankers increasingly confronted what David Rockefeller of Chase National Bank later called “an avalanche of paper,” the need to use electronic computers for less costly and more efficient recordkeeping became urgent. The transition to the computer age produced its own headaches. For example, after spending millions of dollars to develop a mechanical sorting machine to process checks and customer statements during the 1950s, First National City Bank dumped the large machine off a barge into Brooklyn’s Gravesend Bay when a new check encoding system made it obsolete. In 1974, when a janitor mistakenly threw away the spare parts for Chase Manhattan Bank’s aging UNIVAC computer, office staff had to return to manual bookkeeping until a new IBM mainframe computer was installed months later. Progress in the American Century, it turned out, was not a seamless process.4

Wurts Bros., Manhattan Savings Bank, Canal Street and Bowery, January 23, 1963.

Museum of the City of New York, X2010.7.1.10267

To attract neighborhood depositors, the Manhattan Savings Bank introduced Asian motifs and Chinese signage in its Chinatown branch in 1963.

Getting Around Glass-Steagall

Beneath the compliance with conventions and government regulations, New York bankers continually sought ways to build their business in an era of industrial growth and expansion. During the mid-1950s, mergers became a key strategy through which commercial banks consolidated and amplified their financial resources. Banks whose clients included large corporate borrowers courted other banks to acquire their deposits and their networks of deposit-accumulating retail branches located throughout the city. The result, in David Rockefeller’s words, was “a veritable mating ritual of mergers.” In 1955, National City Bank and First National Bank merged to become the First National City Bank, and Chase National Bank merged with the Bank of the Manhattan Company (Aaron Burr’s 1799 creation, which now possessed 58 retail branches in the city) to become Chase Manhattan Bank. That merger made Chase Manhattan the second largest bank in the world with total assets of almost $8 billion, behind only California’s Bank of America. By 1962, eight years of mergers had resulted in several strong conglomerate banks that made “wholesale” loans to corporations and offered “retail” checking and savings accounts and financial services to depositors: First National City, Chase Manhattan, Chemical Bank New York Trust Company, Bankers Trust, Manufacturers Hanover, and Morgan Guaranty Trust Company. During this era, over one-third of New York City’s banks went out of existence, largely through such mergers.5

Another deposit-seeking strategy was to follow customers who moved out of the city. By the late 1950s, as middle-class New Yorkers moved to surrounding suburbs, taking their paychecks and savings with them, suburban deposits were a tantalizing lure to Wall Street and Midtown banks. Banks were already following potential depositors as they moved into newly developing residential neighborhoods in Queens and Staten Island, but such efforts were thwarted at the city’s borders by government regulations. Federal prohibitions on interstate branch banking kept New York banks out of adjoining New Jersey and Connecticut. New York State laws enacted in 1927 and 1934 also kept New York City National Banks from entering suburban territories within the state. When a new federal law in 1956 seemed to imply that urban National Banks and suburban banks could legally merge by forming holding companies, bankers in nearby Westchester County and Long Island opposed it, arguing that big city banks with their superior resources would hurt competition if permitted to encroach. In 1960, however, a revised New York State law permitted New York City banks into Westchester and Nassau counties, with some geographical prohibitions. First National City became the first to open a suburban branch, in Plainview, Long Island, in October 1960; by 1966 the bank would have 36 branches in Nassau and Westchester, where it would compete with other New York City banks as well as local suburban banks. In the early 1960s the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Reserve Board, concerned about maintaining banking competition, blocked attempts by Chemical Bank New York Trust Company, Chase Manhattan, and Morgan Guaranty Trust to expand further by merging with suburban banks or forming holding companies with them. Nevertheless, Wall Street and Midtown banks had decisively arrived in the suburbs. The primary goal was the same: to accumulate deposits to fund loans.

In the mid-1950s “there was a veritable mating ritual of mergers.”

David Rockefeller

Creating the Credit Card

The Everything Card, the Chase Manhattan Charge Plan, and Beyond

In the summer of 1967, First National City Bank mailed their new credit card, the Everything Card, to over a million New Yorkers. The mass mailing was intended to solve a problem faced by new credit cards: consumers did not want a card that merchants would not accept, but merchants would not accept a card until it was in the hands of consumers. The Everything Card strategy backfired. Most New Yorkers did not appreciate receiving credit cards they had not asked for, while others saw an easy opportunity to steal cards and make sham purchases. The bank was quickly overwhelmed by fraud. Unable to convince consumers and retailers to accept the new card, in the fall of 1968, First National City canceled the Everything Card program. First National City was in good company among New York’s banks that tried—with little success—to establish viable credit cards throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Nevertheless, these efforts, with long-forgotten names like the Everything Card and the Chase Manhattan Charge Plan (CMCP), were essential steps on the road to the modern credit card.

The development of consumer credit had been pioneered not by bankers, but by car companies and department stores. Beginning in the 1920s, car manufacturers sponsored and developed sales finance companies, which extended installment credit for the purchase of cars, as well as appliances and other consumer goods. At the same time, department stores started to issue the first pocket-sized cards that allowed customers to purchase goods without cash. Many of these early cards were “Charga-Plates,” small metal rectangles embossed with the customer’s name and address. Unlike modern credit cards, early department store charge accounts were intended to promote customer loyalty and increase sales, not to charge interest, and customers were expected to pay their bill in full at the end of the month.

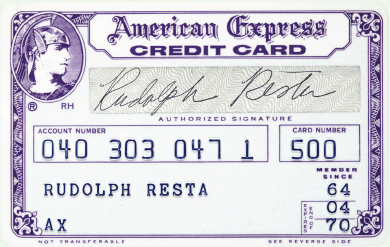

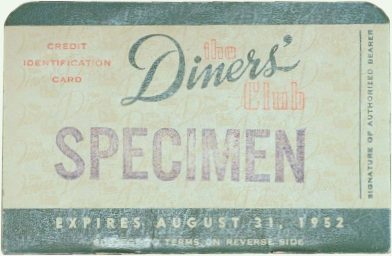

American Express credit card, 1964.

American Express Corporate Archives

The Diners’ Club Credit Identification Card, ca. 1952.

National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

In the years after World War II a new kind of consumer credit emerged—revolving credit. Purchases on revolving credit accounts at stores such as Bloomingdale’s were paid off over time, with interest, and by 1949, 75 percent of America’s major retailers offered revolving credit programs. Beginning in 1950, Diners Club and American Express developed charge cards that could be used at upscale restaurants, hotels, and other businesses across the country, but these charge accounts—like the early department store charge accounts—were about convenience, not credit. Wealthy Americans paid for the privilege of owning a Diners Club Card, and they were expected to pay their bills in full each month. The bank credit card would combine these two innovations, creating a card accepted everywhere that offered a line of revolving credit.

Headquartered at 65 Broadway, American Express considered issuing a travel charge card in 1946, but not until Diners Club posed a threat to its traveler’s check business did American Express create its own credit card. Launched in 1958, it carried a fee of $6—one more dollar than that of Diners Club—and became the industry’s first plastic card when the company replaced the original paper design eight months after the launch. The product did not start earning profits until 1967, when the charges made by the company’s more than 2 million customers totaled $1.1 billion.

Banks looked to capitalize on the boom in Americans’ use of consumer credit, which rose from 38 percent of all households in 1949 to 54 percent by 1958. That year, the two largest banks in the United States, Chase Manhattan and San Francisco-based Bank of America, decided that they could make the bank credit card work. Small commercial banks had been experimenting with charge cards since Franklin National Bank of Long Island introduced the first bank credit card in 1951. Although local merchants initially embraced the opportunity to compete with big department stores and their generous credit departments, early bank credit cards suffered significant losses. The main problem was scale—it just wasn’t possible for a local bank to earn enough money from a credit card operation to pay the back-end costs of processing payments, signing up merchants, and advertising. Bank of America and Chase Manhattan believed that their size and expertise would allow them to succeed where smaller banks had failed and finally break into the nation’s booming consumer credit market. Both banks had reason to be optimistic, but only Bank of America would see its credit card take off.

In 1962, Chase sold CMCP after four years of losing money, stymied by many of the same problems that had plagued earlier bank credit cards. The program could not make enough money to cover its higher than expected operating costs. Perhaps the most important factor in the failure of CMCP, however, was that Chase’s management simply did not believe in the potential of credit cards. In the words of George Roeder, an executive at the bank, “it is unlikely that CMCP will ever grow to the point that it will become an important producer of earnings.”6

Across the country, Bank of America had a very different attitude about their deficit. They used clever accounting to disguise their losses and excluded advertising and other overhead costs from the program’s budget. Bank of America doubled down on Bank Americard, and after millions of dollars in losses, the card finally turned a profit in 1962, growing faster every year. Bank Americard’s success required four years of intensive investment in signing up merchants, advertising to consumers, stemming fraud, and creating the infrastructure to process credit transactions, all while losing money. But the gamble paid off. Bank of America made $33.4 million between 1962 and 1966, and that year the bank announced that it would license Bank Americard to other banks across the country, establishing a nationwide credit card network.

Thus, by the time First National City Bank introduced the Everything Card to New York City in 1967, the rise of the bank credit card was beginning to look inevitable. Between 1956 and 1967, installment credit increased by 146 percent in the United States, from $31.7 billion to $77.6 billion, during the same years that American disposable personal income increased by 86 percent. When a manager at Bank Americard called this “consumer credit explosion” a “revolution in modern banking,” it was not just marketing hyperbole.7

Brochure advertising First National City Bank’s “The Everything Card,” 1967.

Heritage Collection–Citi Center for Culture

Having dropped its Everything Card, in 1968 First National City Bank joined a fast-growing network of banks offering a new kind of credit card: Master Charge. Master Charge allowed its member banks to tap into an existing credit card network, giving small and large banks alike access to the economies of scale necessary for profit. Member banks could issue Master Charge cards without worrying about processing costs or convincing retailers to accept an unfamiliar card.

Meanwhile, Bank Americard had grown too quickly for Bank of America to manage effectively. By the late 1960s, Bank Americards were issued by hundreds of banks to millions of card holders. In the words of one banker, it was “millions of dollars floating all over hell’s half-acre in back rooms.” The poorly run system was overwhelmed by distrust, fraud, and the sheer quantity of paper sales slips.8

In spring 1969, Bank Americard broke free of Bank of America and became the property of the newly created National BankAmericard Inc. (NBI). NBI was owned and controlled by all of the banks that issued Bank Americards. Like Master Charge, it was a national network, controlled by its member banks. By 1971, 1,535 banks offered credit cards, compared to 390 in 1967, and virtually all of them were part of either the Bank Americard or the Master Charge network. In 1969, Chase Manhattan repurchased CMCP, which had been renamed Uni-Card, and in 1972 Chase and Uni-Card joined the Bank Americard network, which would soon be renamed VISA. Networks like VISA and Master Charge allowed banks to compete on interest rates and services while cooperating on the financial infrastructure and costly computer networks that made nationwide credit cards possible.

The failures of CMCP and the Everything Card, and Bank of America’s inability to manage the Bank Americard system, made clear that running a credit card operation was beyond the ability of any single bank. By 1977, however, bank credit cards had found their way into the wallets of nearly 40 percent of American families. With a quick swipe, people could use credit not just to fill up their gas tank or purchase a meal, but to buy virtually everything.

—Bernard J. Lillis

Negotiable CDs and One-Bank Holding Companies

While mergers and suburban expansion helped generate deposits from retail customers, they did not solve another part of the problem: the increasing difficulty banks had in garnering deposit funds from the large and wealthy corporations to which they made loans. Facing government-imposed limits on the interest they could earn from bank deposits, the driving engines of the postwar American economy—corporations like IBM, Ford Motor, Xerox, and U.S. Steel; utilities; and electronics, aerospace, petroleum, chemical, and telecommunications firms—put millions of dollars into more profitable investments, such as Treasury bills or less-regulated mutual funds sold by brokers and investment firms. Corporations also increasingly resorted to nonbank alternatives for borrowing by issuing their own short-term commercial paper and bonds as IOUs to pension funds and insurance companies that lent to them, or plowed their own profits back into their assembly lines rather than borrowing. As corporations opened more plants in the growing “Sunbelt” of the South and West, they also threatened to do a greater proportion of their business with regional banks there. In order to be able to make loans and to offer attractive borrowing rates to corporations, New York banks needed somehow to find a way around Glass-Steagall rules that kept them from accumulating working capital from the same types of big businesses they wanted to lend to.

By 1959, bankers at First National City Bank (located at 55 Wall Street) were among those trying to solve the deposit problem. The head of the overseas division, Walter Wriston, and his boss and mentor, bank president George S. Moore, were already among the era’s top banking innovators. For example, when other banks continued to rely almost exclusively on short-term lending to businesses, Moore and Wriston promoted the use of long-term loans (called “term loans”), allowing entrepreneurs up to five years (and later ten years) to pay. Moreover, they innovated by permitting these borrowers to secure the loans by treating their companies’ projected future cash flows (not just the physical plant itself) as collateral, thereby increasing the amount of money that First National City Bank was willing to lend. These initiatives allowed the bank to become the major commercial banker to the Greek oil supertanker magnates Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos; to American and European airlines eager to buy jet passenger planes from the aeronautics producers Douglas Aircraft and the Boeing Company; and to Malcom McLean, the pioneer of the new container ships that transformed world maritime traffic (and the commerce of the port of New York). All of these borrowers needed term loans to afford the expensive new technologies revolutionizing their industries in the 1950s and early 1960s; First National City Bank became the world’s largest ship-financing bank and lent millions to airlines, railroads, and trucking firms. Wriston, a restless proponent of the need to combat or sidestep what he viewed as tyrannical and senseless government banking regulations, was also eager to find a solution to the deposit crunch.

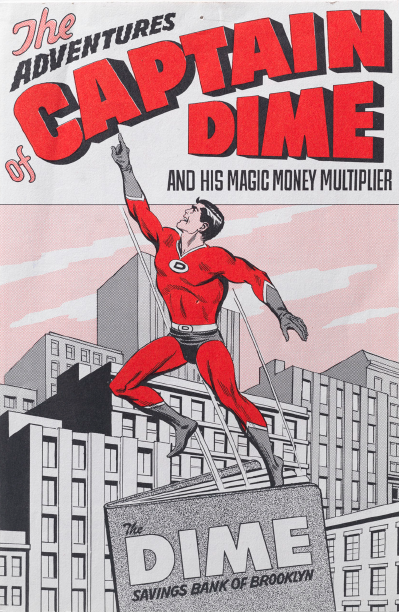

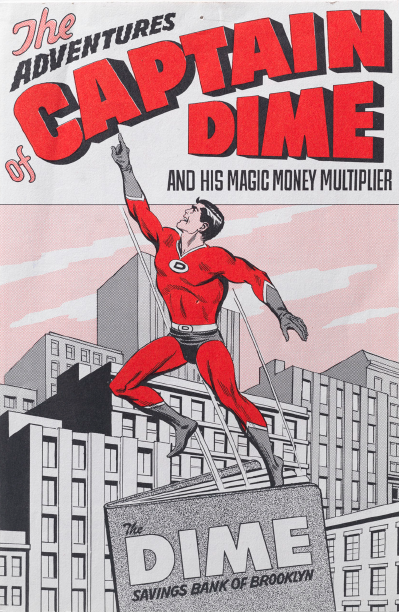

“The Adventures of Captain Dime,” advertisement for Dime Savings Bank of Brooklyn, 1967.

Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection

Educating customers—or potential customers—on the activities and purposes of banking was a crucial activity for financial institutions in the postwar era.

In 1961, Wriston and his colleagues devised just such a solution, and in doing so revolutionized commercial banking. Their negotiable certificate of deposit was a new type of financial instrument that offered corporations and wealthy investors interest like a savings account but also could be traded as a security. Such a CD required a minimum investment of $100,000. Corporations could sell the CDs on the open market if they were in immediate need of cash, making them desirable assets competitive with the nonbank investments to which corporation treasurers had increasingly turned. Rather than relying only on deposits, commercial banks could now sell a popular and lucrative product to accumulate capital.

Negotiable CDs brought millions of dollars into First National City Bank, swelling the base of funds that could be loaned, and the innovation was immediately copied by the city’s and nation’s other major commercial banks. They did so with the acquiescence of the Federal Reserve Board, proving that banks could find ways around government regulations and free themselves from their reliance on deposits. (“Regulators sit by while snails go by like rockets,” Wriston later complained, but he benefited from the willingness of federal officials to tolerate innovations when they appeared to promote economic stability.) For Wriston, who believed that Regulation Q might soon so limit operations as to spell the end of profitable commercial banking, such innovations were survival mechanisms as well as profit makers. As he later put it, the negotiable CD “probably changed the world [of banking] as much as anything.”9

Later in the 1960s, New York banks also resorted to another highly useful instrument, the one-bank holding company. According to federal and state law, a bank could create a holding company and then make itself the holding company’s wholly owned subsidiary. In the words of the historians Harold van B. Cleveland and Thomas F. Huertas, a bank could thus give “birth to its own parent.” The advantage of this was that the holding company was not a bank, and thus was not constrained by the Glass-Steagall Act or state banking laws. These companies could engage in a whole array of financial activities that their “child” banks under Glass-Steagall could not, including selling insurance, writing otherwise-restricted types of mortgages, offering management consulting, and marketing certain financial products across state lines. They could also make commercial loans and place the revenues derived from them in their “child” banks. In 1968, under Walter Wriston, now the bank’s president, First National City Bank created its holding company, the First National City Corporation (renamed Citicorp in 1974). Morgan Guaranty Trust followed suit in 1969 by creating the one-bank holding company J. P. Morgan and Company, Inc., and Chase Manhattan and other large banks also formed one-bank holding corporations. In doing so, they furthered the new vision embraced by Wriston and other New York bank executives, enunciated by George Moore at First National City Bank in the early 1960s: “We would not be merely a bank. We would become a financial service company. We would seek to perform every useful financial service, anywhere in the world.”10

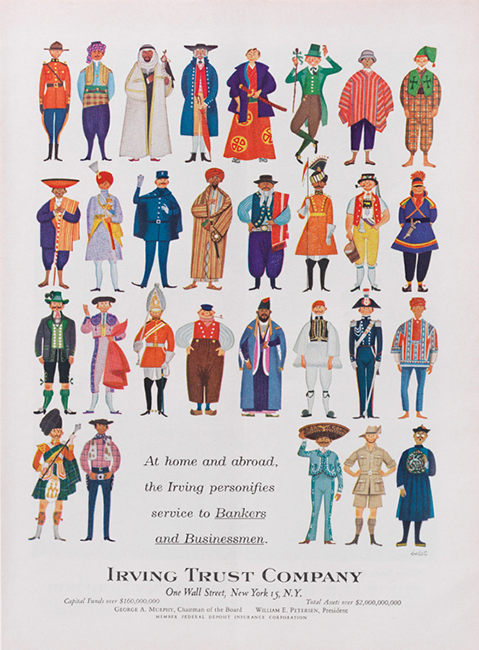

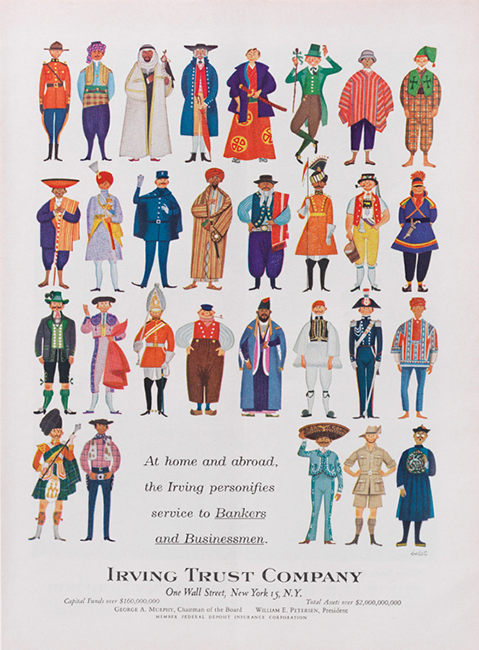

Advertisement for Irving Trust Company, 1963.

Private collection

Like other New York banks, Irving Trust promoted its global business. Following World War II, the bank held the account of Japan’s Exchange Board, which controlled the country’s use of money made from foreign trade.

“We would not be merely a bank. … We would seek to perform every useful financial service, anywhere in the world.”

George Moore

Global Banking, Wriston Style

Going anywhere in the world was, indeed, increasingly part of the repertoire of New York banks in the postwar decades. While they devised methods to circumvent Glass-Steagall legally at home, they also followed American corporations expanding globally. Serving the needs of American multinational corporations as they set up operations abroad was one incentive for this expansion, especially since the multinationals often placed deposits in the banks’ New York home offices. Another incentive was the perceived need to compete with European and, increasingly, Japanese banks for customers wherever they might be found. New York banks opened new branches and representative offices in countries where government policy permitted them to do so; in countries where laws limited or proscribed the entry of foreign banks, New York banks made their presence felt by buying ownership or part-ownership in existing local banks. In 1960, a New York State law allowed foreign banks to do business in the state, inaugurating an influx of European, Asian, and other banks into New York City; many New York bankers supported the change, since it encouraged foreign governments to lower their own barriers against the entry of New York’s banks into their national territories and markets.

In 1963 Walter Wriston described a three-pronged First National City plan to become global: the bank had to put “a branch in every commercially important country in the world,” tap into the “local deposit market,” and “export retail services and know-how from New York.” The formula worked. Between 1960 and 1967, National City Bank grew its foreign deposits and commercial and industrial lending, opening 85 branches abroad—54 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 14 in East Asia, 15 in Europe, and two in the Middle East. While other New York banks also made strong showings globally, including Chase National Bank in lending to the postwar Japanese government and to Latin American exporters and Chemical Bank in foreign exchange, no American bank matched First National City’s global reach.11

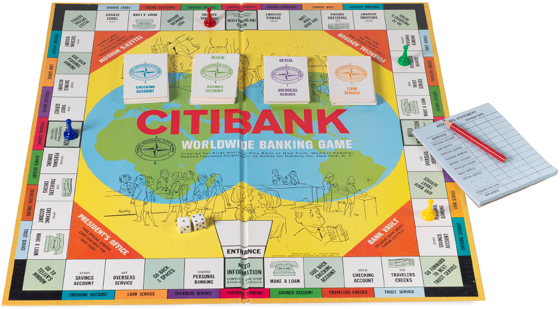

Citibank Worldwide Banking Game, 1964.

Heritage Collection-Citi Center for Culture

This board game distributed by the First National City Bank encouraged players to think like New York bankers as they extended their global reach during the 1960s.

Global expansion tantalized New York banks with the lure of vast amounts of capital beyond the purview of American regulations. Another innovation marketed by First National City Bank in 1966, the Eurodollar certificate of deposit, played a pivotal role in drawing these foreign funds to Wall Street. Eurodollars were the balances in U.S. currency that accumulated in accounts abroad as Americans spent dollars on foreign goods and foreign travel. Ironically, Eurodollars had originally emerged as a by-product of the Cold War, when Soviet bloc nations kept dollar deposits in London and Paris banks rather than risk the accounts being seized or frozen by the U.S. government if they were placed in New York banks. Wriston’s new Eurodollar CD permitted overseas banks and investors to buy interest-bearing CDs with Eurodollars. This enabled First National City Bank to attract foreign dollars into its New York City deposit base while paying interest rates to CD buyers abroad that were not limited by Regulation Q. Once again, Wriston’s bank had devised a lucrative instrument for getting around Glass-Steagall, this time on the global stage.

Global Banking, Rockefeller Style

Although Walter Wriston of First National City Bank (renamed Citibank in 1976) was the most successful global expansionist, another New Yorker, David Rockefeller of Chase Manhattan, gave him a run for his money. The grandson of John D. Rockefeller, the petroleum tycoon who had founded Standard Oil, he grew up enjoying great wealth in a family with venerable connections to New York banks. After studying at Harvard and the London School of Economics and earning a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago in 1940, Rockefeller worked as a secretary to New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Following wartime military service, he was hired in 1946 by his uncle, Winthrop W. Aldrich, president and chairman of Chase National Bank, who also happened to be the son of the Rhode Island Senator Nelson Aldrich, who had helped create the Federal Reserve System.

At Chase, Rockefeller’s energetic globetrotting came to resemble that of earlier Wall Street “banker-diplomats”—most notably J. P. Morgan partner Thomas W. Lamont—who had worked closely with the White House and State Department in the 1920s and 1930s to further American business and political influence abroad while they made loans to foreign governments and businessmen. Indeed, in the postwar era, the link between Washington and Wall Street was strong, despite their ostensibly adversarial relationship since the New Deal. The Washington-based World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, both proposed at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference where the Allies planned the postwar world economy, connected Wall Street to government policy. The World Bank’s second president from 1947 to 1949, John J. McCloy, was a Wall Street lawyer who would go on to become chairman of the Chase National and then the Chase Manhattan Bank; his successor at the World Bank from 1949 to 1963, Eugene R. Black Sr., a former Chase National senior vice president, came to rely on New York’s Morgan Stanley and First Boston to organize large syndicates that underwrote the World Bank bonds that helped pay for global loans and development. During the Cold War, New York bankers also became useful eyes and ears for the State Department and the White House as they ventured abroad.

As he became Chase’s co-CEO (1961) and CEO (1969), Rockefeller maintained an internationalist worldview and strove to compete in global markets with what he viewed as Chase Manhattan’s “archrival,” First National City Bank, as well as with the other leading international players such as Chemical Bank, Morgan Guaranty Trust, and San Francisco’s Bank of America. An economic conservative, Rockefeller was nonetheless a fixture of the Republican Party’s anti-isolationist “Eastern” wing, and he believed that private banks, national central banks, and governments needed to work together to equalize economic opportunities and democratize countries around the world. In 1948, for example, he urged that Chase make loans to Caribbean nations in such a way as to “raise their standard of living through improved agriculture, more efficient distribution and increased industrialization.” Rockefeller saw himself as an “ambassador without portfolio,” and in 35 years at Chase he personally visited 103 countries. (In response, George S. Moore of First National City Bank asserted wryly, “We’ll let David talk to the kings … [But] we’ll get the business.”)12

Like Wriston at First National City, Ralph Leach and Henry Alexander at Morgan Guaranty Trust, and his other major competitors, Rockefeller embraced tactics that skirted Glass-Steagall’s separation of commercial and investment banking. Along with its rivals, Chase Manhattan used the 1919 Edge Act, a federal law that permitted commercial banks to engage in investment banking activities outside the United States. The Chase International Investment Corporation (CIIC), founded on the basis of the Edge Act in 1957, allowed the bank to invest funds directly in a Nigerian textile mill, an Iranian development bank, an Australian land development corporation, and numerous other foreign enterprises. Expansion continued; by the early 1980s Chase Manhattan would have branches or offices in over 70 countries, and in 1981, when Rockefeller stepped down as Chase CEO, the majority of the bank’s income—$247 million—came from international operations.

Reshaping Manhattan

As they expanded their reach worldwide, banks also transformed New York’s cityscape. Although the Glass-Steagall Act barred the city’s commercial banks from underwriting corporate securities, they were still able to underwrite municipal bonds, making them unofficial partners of and advocates for public works projects. Through such bond issues, banks remade the real estate market of New York. They underwrote residential projects, including the largest public housing system in the country, as well as private residences (through traditional mortgages and, increasingly, loans to co-op owners, who had been historically hard pressed to get credit). Banks also sold bonds for the city’s bridge, tunnel, and road projects, and for Robert Moses’s Triborough Bridge Authority, which funded construction projects such as the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge (built 1959–1964) by partnering with banks to sell bonds that would be repaid through anticipated toll revenues. Meanwhile, during the 1960s, banks such as First National City helped fuel the urban and national building boom by entering the commercial real estate mortgage market aggressively; First National City had $9 million outstanding in commercial real estate loans in mid-1961, and six years later the amount had risen to almost $164 million.

In this era, banks themselves were leaving the narrow canyons of Lower Manhattan for the new sunlit plazas of Midtown, following the uptown migration of the corporate headquarters whose accounts were vital to their profitability. Many Wall Street banks had opened Midtown branches and satellite offices by the late 1950s; now their headquarters abandoned the downtown financial district as well. By 1963, the main offices of First National City Bank, the Bank of Tokyo Trust Company (a telling new arrival), and others were located in Midtown towers. Investment banks as well as commercial banks joined the northward movement. When Morgan Stanley’s Robert Baldwin told Andre Meyer of Lazard Freres that some Morgan Stanley partners resisted the idea of moving from their 2 Wall Street offices, Meyer, now based in Rockefeller Center, laughed and replied, “Fine … I’ll be having lunch uptown with your clients while you’re having lunch downtown with your competitors.” Taking Meyer’s message seriously, Morgan Stanley moved to the Exxon Building at Avenue of the Americas and West 50th Street in 1973.13

Ezra Stoller, Manufacturers Trust, 510 Fifth Avenue, 1954.

©Esto

With its vault door visible from Fifth Avenue, the new Midtown branch of Manufacturers Trust, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and opened in 1954, immediately became a statement of postwar modernism in architecture and interior design. On its first day, 15,000 visitors swarmed through the bank. Its opening marked an era in which Wall Street banks increasingly followed corporate headquarters to Midtown Manhattan.

Fearing the economic impact of the migration on Chase Manhattan properties in the Wall Street area, as well as the broader implications for the financial district’s future, David Rockefeller founded the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (D-LMA) in 1958 and gained the participation of top executives and officers at AT&T, J. P. Morgan, National City Bank, the Seamen’s Bank for Savings, U.S. Steel, the New York Stock Exchange, and other firms headquartered downtown. Robert Moses, the city’s master planner, had warned Rockefeller that any attempt to reaffirm Chase Manhattan’s presence in the financial district would be a costly mistake if he did not also try to revitalize the entire district. Collaborating with Moses and state and city authorities, D-LMA ultimately offered sweeping plans for the rehabilitation of all of Lower Manhattan below Canal Street as a mixed commercial, financial, and residential zone that could compete with the attractions of Midtown Manhattan and maintain the Wall Street district’s survival and viability.

Some of D-LMA’s specific proposals were never implemented, most notably Moses’s plans for a Lower Manhattan Expressway cutting across downtown neighborhoods to link the East and West Sides, which provoked a successful resistance from community residents, activists, and politicians. But two projects of special importance to Rockefeller did go forward. One was the construction of One Chase Manhattan Plaza as a skyscraper home for his bank on a cleared site built over Pine and Cedar Streets, one block from Wall Street. Designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the 60-floor office tower, completed in 1961, was the first significant construction project in the vicinity for decades; Rockefeller intended it as a “statement building” to anchor the revival of the Wall Street area and signal Chase Manhattan’s identity as a “progressive institution” unafraid of positive change. The other project was the World Trade Center, undertaken by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey at Rockefeller’s urging and intended as a mixed commercial, financial, retail, and transit complex. Its two towers, which became the tallest buildings in the world, were dubbed “David” and “Nelson” (referring to the Chase Manhattan CEO and his brother, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller) when excavation at the site began in 1965. A transformed Lower Manhattan, one that competed with Midtown by being more amenable to large new office towers housing corporations and banks, emerged from these endeavors in the 1970s and 1980s.14

Controversies

For New York banks and bankers, the American Century was not without its controversies. Old suspicions of Wall Street persisted into a new era, although they lacked the fuel of the pervasive public outrage that had driven the reform crusades of the Progressive and New Deal periods. In 1947 President Harry S. Truman’s Justice Department filed suit against 17 major investment banks, dubbed the Club of 17, and their trade group, the Investment Bankers Association. The “club’s” most prominent members included tried-and-true Wall Street veterans: Morgan Stanley; Kuhn, Loeb; Goldman, Sachs; First Boston; and Dillon, Read. The Justice Department alleged that the defendants had conspired to keep their corporate clients from moving their accounts to other banks within or outside the group, thereby violating the provisions of the federal Sherman Antitrust Act (1890). In a juryless trial that dragged on in a Foley Square federal courtroom for six years, Judge Harold Medina ultimately ruled in 1954 that the charges were groundless; no evidence proved the existence of a conspiracy by investment bankers to restrain trade. Thus, echoes of the “Money Trust” accusations made by earlier crusading reformers such as Brandeis, Untermyer, and Pecora were heard but then largely faded.

Eric Locker, Chase Manhattan Bank building, center, ca. 1961.

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

When completed in 1961, the new 60-story Chase Manhattan Bank headquarters in Lower Manhattan became the third tallest building in the financial district and the sixth tallest in the world.

Blacker-Amster, David Rockefeller, left, with model of Lower Manhattan, June 10, 1968.

Rockefeller Archive Center

David Rockefeller lays out plans for the development of Lower Manhattan, which between 1958 and 1973 brought nearly 47 million square feet of new office space to the area and increased the workforce by 500,000.

More challenging were the angry protests by African American activists and their white allies against racial discrimination in banking. In 1948 a leftist-led CIO union, the United Office and Professional Workers of America, won pledges from the Royal Industrial Bank and the Merchants Bank to hire African American New Yorkers in white-collar positions. In search of credit, some African Americans sought to rely on themselves: in 1949, 800 Harlem residents pledged assets of $225,000 to open Carver Federal Savings and Loan Association, the city’s first black-owned and operated savings and loan institution. Nevertheless, the discriminatory policy of “redlining” adopted during the 1930s by the Federal Housing Agency, commercial banks, and other mortgage lenders (see Chapter Six) continued to shape the social geography of New York and many other cities. Redlining channeled residents into racially and economically segregated districts by denying mortgages to African Americans, Puerto Ricans, and sometimes Jews who sought to move into “desirable” neighborhoods and suburbs. In 1946, a federal antitrust indictment implicated the Mortgage Conference of Greater New York, a consortium of 38 bank and trust companies, for inducing “owners of real estate in certain sections of New York City to refuse to permit Negroes and Spanish-speaking persons to move into such sections.” But the breaking up of the consortium and its members’ agreement to curtail such practices failed to end the larger pattern of segregation. A 1948 survey found that lender-backed restrictive covenants against selling homes to minority buyers governed 85 percent of new large subdivisions in Queens, Westchester, and Nassau counties. “Is this New York or Mississippi?” a black home seeker asked in Harlem’s Amsterdam News in 1953 when realtors refused to show her new homes in Queens.15

In the wake of World War II, a conflict ostensibly fought by Americans to extend democracy and freedom for all, black New Yorkers took to picket lines, protest rallies, and political pressure to denounce the collaboration of banks, realtors, and government agencies in keeping African Americans penned up in overpriced, overcrowded, decaying slum neighborhoods in Harlem, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. Protesters in the late 1940s—a diverse group that included Communist Party members, NAACP and American Jewish Congress activists, Harlem church congregants, and others—formed picket lines outside the Midtown branches of institutions they accused of mortgage discrimination, such as Empire City Bank. “Are the Big Banks and the Insurance Companies More Powerful Than the U.S. Courts?” asked the signs carried by black and white demonstrators, encouraged by recent antidiscriminatory court decisions, outside the Foley Square courthouse in 1949. New York’s City Council responded in 1954, passing the Sharkey-Brown-Isaacs Law, the nation's first legislation barring racial discrimination in all future private multiple dwellings (of three or more units) built with government-guaranteed loans. Democratic Governor Averell Harriman, formerly a prominent Wall Street investment banker and diplomat, signed a similar New York State law in 1955 that extended such protections statewide to larger housing developments.

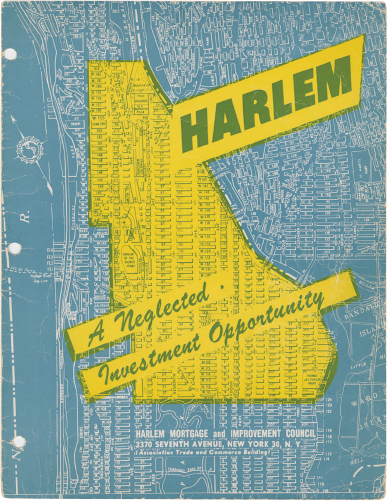

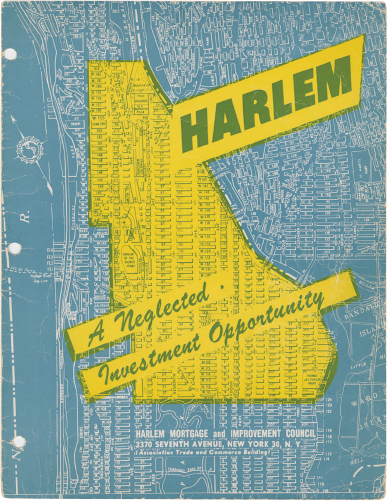

“Harlem: A Neglected Investment Opportunity.” Published by Harlem Mortgage and Improvement Council, 1951.

Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Harlem civic leaders tried to encourage banks to make loans in their neighborhood by publicizing its amenities, its low foreclosure rates, and the community’s need for more bank credit. The Harlem Mortgage and Improvement Council published several reports like this one to attract bank investments.

Such laws, however, did not prevent commercial and savings banks from refusing to lend mortgage money to individual black and Latino borrowers. Nor did laws prohibit banks from refusing to offer or renew business and residential loans in minority neighborhoods deemed to be decaying, as increasingly happened in the Bronx and Brooklyn by the late 1960s and 1970s. Although bankers were not solely responsible for the racially charged “urban crisis” that erupted in the mid-1960s, they contributed to it, as did federal bureaucrats, real estate companies, “urban renewal” planners, landlords, racist or fearful white homeowners, and others. The battle fought by some New Yorkers against redlining would continue in future years (see Chapter Eight).16

“War Au-Go-Go”

In foreign affairs too, New York banks became a target for growing criticism. For student activists and others busy creating a New Left in the early and mid-1960s, banks were not the force for salutary modernization and global democracy that David Rockefeller and others claimed. Instead, Wall Street was viewed as an architect of American efforts to dominate the economies and governments of other nations in order to safeguard capitalist profits and exploit the world’s working class, especially in postcolonial Third World countries.

Indeed, the New York banks were a conspicuous presence in what Dwight Eisenhower had labeled the military-industrial complex. As businessmen with their fingers on the pulse of foreign as well as domestic developments, Wall Street financiers were courted by the Cold War presidents. Brown Brothers Harriman’s Robert Lovett was Harry Truman’s Secretary of Defense during the Korean War. Eisenhower relied on J. P. Morgan’s George Whitney for advice, while John Kennedy picked investment banker C. Douglas Dillon of Dillon, Read as his Secretary of the Treasury (other candidates included Henry C. Alexander of Morgan Guaranty Trust and John J. McCloy). Lyndon Johnson heeded the counsel of McCloy, who, in addition to having headed the World Bank and been chairman of Chase Manhattan, had also served as U.S. High Commissioner for postwar Germany and now chaired two New York-based institutions, the Ford Foundation and the Council on Foreign Relations. For these men, as for Johnson, the presence of a Marxist government in North Vietnam raised the specter of potential communist expansion throughout Southeast Asia. For young radicals, though, the assertive Cold War anticommunism of these “Establishment” banker-public servants went hand in hand with Washington’s support for repressive and corrupt right-wing regimes and ruling elites around the world. New York banks’ loans to foreign governments and businesses, loans to and securities issues for American military contractors, and support for White House and Pentagon policies all appeared to strengthen the forces most averse to the global redistribution of wealth and power from entrenched minorities to popular majorities.

The Vietnam War was the trigger for activist denunciation of New York’s corporations, markets, and banks. On April 14, 1966, some 75 members of Youth Against War and Fascism, a Marxist-Leninist student group, picketed the New York Stock Exchange by marching in a circle in front of the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company of New York, J. P. Morgan’s old headquarters, across Broad Street from the exchange. Their placards read, “Big Firms Get Rich—G.I.s Die” and “What’s Good for G.M. Isn’t Good for G.I.s.” Soon they were scuffling with members of a right-wing Brooklyn-based group called American Patriots for Freedom, angry brokers’ messengers and exchange clerks, and, according to The New York Times, “several well-dressed men who flailed at the demonstrators with attaché cases.” On May Day 1967, Youth Against War and Fascism returned to Wall Street, this time with placards reading “We Won’t Fight Wall Street’s War” and “War Has a Friend at Chase Manhattan” (a parody of that bank’s ubiquitous advertising slogan, “You Have a Friend at Chase Manhattan”). The police maintained order between the leftists and a jeering crowd of about 1,000 male Wall Street employees who yelled “Commie scum” and “Traitors” and proudly waved their draft cards from the sidewalk in front of the stock exchange.17

Walter Wriston (third from left) and David Rockefeller (fifth from right) with President Lyndon Johnson (standing) at the White House, August 10, 1967.

Heritage Collection-Citi Center for Culture

Like other presidents, Lyndon Johnson turned to New York bankers for economic and foreign policy advice. The bankers were among 12 leading businessmen Johnson gathered for an off-the-record meeting to address the growing budget deficit. In addition to Wriston and Rockefeller, Goldman Sachs’s Sidney J. Weinberg, Morgan Guaranty Trust’s Thomas Gates, Jr., and Bank of America’s Rudolph Peterson were in attendance. The group agreed that 25 percent of the gap should be closed with tax increases and 25 percent through budget cuts, and that borrowing would make up the other 50 percent.

When David Rockefeller rose to receive an honorary degree at the 1969 Harvard University commencement, a member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) armed with a loudspeaker harangued the audience with an indictment that linked campus politics and global policy: “David Rockefeller needs ROTC [Reserve Officers’ Training Corps] to protect his empire, including racist South Africa, which his money maintains.” At the Woodstock concert in upstate New York that summer, the musician Country Joe McDonald regaled 400,000 young people with his anti-Vietnam War anthem “I Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” in which he sardonically urged “Wall Street” to take advantage of “war au-go-go” by profiting from the Pentagon’s military expenditures. Few in his audience that day realized that Country Joe was invoking a legacy that linked the New Left of 1969 with the Old Left of 1940. McDonald, a devoted fan of an earlier protest singer, Woody Guthrie, knew that almost 30 years earlier, toward the end of the Great Depression, Guthrie had lambasted New York bankers in a song entitled “Jesus Christ” by comparing them to the ancient money changers and other profiteers who, Guthrie charged, had murdered the carpenter from Nazareth.18

Barton Silverman, Youth Against War and Fascism rally along Broad Street from the New York Stock Exchange, May 1, 1967.

The New York Times/Redux

The role played by New York banks and bankers around the world remained controversial in the 1970s, as oil crises and foreign political upheavals challenged American authority abroad and put additional pressures on a domestic economy that showed signs of serious stress after 30 years of unrivaled prosperity and growth. With the first easing of Cold War tensions in the early 1970s, New York banks eagerly sought entry into the Soviet Union and Communist China; Chase Manhattan opened its Moscow office at One Karl Marx Square in 1973 and gained access to China in 1979. At the same time, the presence of communism in the Western Hemisphere was another matter; bankers well remembered that Fidel Castro had nationalized $2 billion in American property, including the assets of New York-based banks, in 1960 after seizing power in Cuba. In 1970 David Rockefeller, alarmed by warnings from a Chilean business friend about the threat posed by the potential election of a Marxist, Salvador Allende, to the Chilean presidency, put the friend in touch with his confidant Henry Kissinger, then serving President Richard Nixon as National Security Advisor. By Rockefeller’s own later assertion, the contact confirmed U.S. intelligence reports that led the Nixon administration to “increase its clandestine financial subsidies to groups opposing Allende.” Nonetheless, Allende was elected to the presidency in 1970 and proceeded to nationalize American property and redistribute land owned by the wealthy to peasants. The extent of the participation of Kissinger, the CIA, and American corporations in the 1973 military coup that deposed President Allende remains a hotly contested topic. As Rockefeller later noted, Allende partisans and labor leaders were “tortured, killed, or driven into exile” by the new regime that held power in Chile until 1990, while young economists from Rockefeller’s graduate alma mater, the University of Chicago, advised the regime’s leaders on restoring free markets.19

The 1970s brought public confrontations over overt American banking policies, as activists assailed banks for doing business with the white segregationist government of South Africa and supporters of Israel denounced Rockefeller for espousing a more “balanced,” less aggressively pro-Israel American Middle East policy at the same time that Chase Manhattan was extending its banking network throughout the Arab world. One thing was certain: New York City banks had become a presence at the juncture of Cold War and, eventually, post-Cold War global finance and politics, a role they had no intention of abandoning.20

Survival and Innovation

In the post-World War II era, New York City bankers felt impeded by government regulations that limited their ability to exploit opportunities in an increasingly prosperous and expansive industrial economy. Commercial banks in particular, deprived of the securities investments and the deposit-attracting interest rates that they had enjoyed before the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, played a catch-up game with American manufacture-based corporations, following them to Midtown Manhattan and to foreign countries to secure their business. In doing so, they grew resourceful, sidestepping regulatory obstacles by relying on mergers, suburban expansion, services and promotions for retail depositors, negotiable CDs, Eurodollar CDs, one-bank holding companies, and other tactics to survive and flourish in a more competitive economy at home and abroad. While the intersection of Wall Street’s and Washington’s world agendas generated controversy and resistance, New York bankers and financiers eagerly resumed the international role they had played between the World Wars.

Their new instruments and strategies, however, would soon begin to transform the culture of New York City banking. As they competed for working capital in CD and Eurodollar markets and depended less heavily on deposits, commercial bankers started to think more like their Wall Street comrades, bond and stock traders and investment bankers, and grew impatient to resume a full-fledged role in the packaging and selling of securities. “Clerks follow the rules. You guys are hired to break the rules,” Walter Wriston told his bankers. In the more economically turbulent era that followed the early and mid-1970s, assertive bankers and financiers would gradually turn the tables on their corporate clients and make themselves the new “stars” of the American economy. They would also continue their efforts to circumvent, and ultimately overturn, the regulatory constraints on banking in place since the Franklin Roosevelt years. First, though, they would play a central role in a vivid urban drama—New York City’s confrontation with bankruptcy and financial disaster.21

Endnotes

1 “Do they do more”: Advertisement, The Commercial Banks of the U.S., Life, Vol. 49, No. 12, September 19, 1960.

2 “American Century”: Henry R. Luce, “The American Century,” Life 10, no. 7 (February 17, 1941), 61–65.

3 “My name is”: Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance (New York: Grove Press, 1990), 501.

4 “an avalanche of”: David Rockefeller, Memoirs (New York: Random House, 2003), 307.

5 “a virtual mating”: Ibid., 158.

6 “it is unlikely”: Quoted in Timothy Wolters, “‘Carry Your Credit in Your Pocket’: The Early History of the Credit Card at Bank of America and Chase Manhattan,” Enterprise and Society 1, no. 2 (2000): 348.

7 “consumer credit”: Quoted in Christine Zumello, “The ‘Everything Card’ and Consumer Credit in the United States in the 1960s,” Business History Review 85, no. 3 (2011): 555.

8 “millions of dollars”: Quoted in Joseph Nocera, A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 68.

9 “Regulators sit by”: Phillip L. Zweig, Wriston: Walter Wriston, Citibank, and the Rise and Fall of American Financial Supremacy (New York: Crown, 1995), 305; “probably changed the”: Harold van B. Cleveland and Thomas F. Huertas, Citibank, 1812–1970 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 256.

10 “birth to its”: Ibid., 296; “We would not”: Ibid., 259.

11 “a branch in”: Ibid., 260–261.

12 “archrival,” “raise their standard,” “ambassador without portfolio”: Rockefeller, Memoirs, 305, 130, 487; “We’ll let David”: Zweig, Wriston, 128.

13 “Fine”: Chernow, House of Morgan, 588.

14 “statement building,” “progressive institution,” “‘David,’” “‘Nelson’”: Rockefeller, Memoirs, 164, 390.

15 “owners of real,” “Is this New York”: Martha Biondi, To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 116, 235.

16 “Are the Big”: Ibid., 117.

17 “Big Firms Get,” “What’s Good for,” “several well-dressed”: Douglas Robinson, “Antiwar Marchers Scuffle With Clerks At Stock Exchange,” The New York Times, April 15, 1966, 1; “We Won’t Fight,” “War Has a,” “Commie scum,” “traitors”: “75 War Protesters Picket Wall Street as 1,000 Jeer,” The New York Times, May 2, 1967, 10.

18 “David Rockefeller needs”: Rockefeller, Memoirs, 334; “Wall Street,” “war au-go-go”: Country Joe McDonald, “I Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” www.countryjoe.com/feelmus.htm (accessed October 9, 2013).

19 “increase its clandestine,” “tortured, killed, or”: Rockefeller, Memoirs, 432, 433.

20 “‘balanced’”: Ibid., 269, 276, 277–278.

21 “Clerks follow the”: Zweig, Wriston, 305.