I’D LIKE TO RAISE A HUGE GLASS of something lovely to whoever it was, somewhere around 3500BC, probably in Egypt, who looked at a pile of sand and thought: ‘Hmm. I wonder what happens if I heat that to an incredibly high temperature, especially if I stir in a bit of potash and/or limestone?’

What happens is a kind of alchemy: the sand melts at around 1700°C/3092°F and becomes a clear-ish liquid that undergoes a complete transformation of its molecular structure and cools to become what we now call glass, a curious substance that is known as an amorphous solid – something with the crystalline structure of a solid but the molecular randomness of a liquid.

Although our Egyptian and his friends first used glass to make decorative beads, it wasn’t long before they were pouring the molten liquid over moulds made from clay to create drinking vessels. It was a slow and laborious process so these early wine glasses were available at vast expense to only the higher echelons of society; it wasn’t until the 1st century BC that some bright spark in Phoenicia hit on the idea of blowing through one end of a tube to inflate a lump of molten glass attached at the other and create hollowed-out glassware that could be shaped by the skill of the craftsman to create vessels that were relatively quick and easy to make.

My father was something of a glass collector. The cupboards of my childhood were filled with an array of glassware. There were flutes for fizz, goblets for claret, heavy crystal tumblers for gins and tonic or whisky, straight-sided Victorian rummers, modern burgundy bowls and exquisite Georgian glasses with air-twist stems tiny enough for only a thimbleful of port or perhaps a nip of madeira.

At ostentatious dinner parties each guest would use at least four different glasses throughout the evening – grown-ups in those days tended to run the full gamut of the booze and then drive home. I have fond childhood memories of mornings-after with a multitude of sticky glasses lined up next to the sink. My father would fill a bowl with soapy water, dredge the glasses through it then rinse them under hot running water and set them upside down on a clean cloth he’d laid on the draining board so as not to chip their delicate rims. Then he’d polish each glass lovingly, holding it up to the light, until it sparkled. I spent years watching this ritual – goggle-eyed, transfixed by the glittering beauty of the glint and the gleam, small feet kicking against the twin-tub – until finally I was allowed to wield the polishing cloth. I have never since felt more adult, more trusted.

The mode of transporting whatever we are drinking into our mouths has a critical bearing on how we relish the whole experience, so it’s worth making the effort to get it right. Riedel make glorious glasses, so light and delicate, as do Zalto, whose outré angular shape and improbably fine stem are wonderful to drink from but can be stressful when it comes to the polishing. I speak from bitter (and costly) experience and advise washing such high-end glassware very carefully and only when sober in the cold light of day. For day-to-day drinking I use something more robust that won’t make me weep if it gets smashed.

Whatever shape or size you choose, look for something with a fine rim so the liquid makes as seamless a transition from glass to mouth as possible. This is particularly important when drinking wine of any sort; aperitifs knocked up over ice are more forgiving of something rather chunkier and, of course, rims don’t really matter if you choose to drink through a straw.

The most important thing to remember is that no glass, whatever its value or beauty, or whatever it holds, is worth drinking out of unless it is gleamingly, dazzlingly clean. Those who know me will attest that I have a pathological obsession with clean glassware, to the point when I will surreptitiously polish my glass with a napkin if they’re not to my exacting standards in a restaurant. I try not to do the same if I’m a guest in somebody’s house but sometimes even then the compulsion is stronger than my sense of decorum. My brother is the same; our father died when we were in our twenties and we like to think of our condition as him keeping an eye on us from the grave.

There is something almost metaphysically beautiful about a semitransparent liquid in a perfectly transparent glass, and how the two behave together. How the glass allows the colour and clarity of the liquid to show itself in its best light, and how the liquid clings to the glass and curtseys, showing its metaphorical ankles and sometimes its legs as well. I am not a fan of the domestic dishwasher for washing glasses – with frequent use they leave an unattractive and indelible cloudy film on the glassware, as well as a vile whiff of U-bends, but then I know people who take their glassware very seriously and swear they’re fine as long as you wash nothing else with them. Feel free to experiment; I’ll be the one at the sink wearing rubber gloves, happily making free with the hot water and suds.

So we come to the matter of the glass cloth for the polishing. Purists (i.e. me) would say a glass cloth should never be used for anything but glasses. It needn’t necessarily be made from 100 per cent Irish linen, though these are the cloths my father favoured, but it does need to be made from good-quality linen and/or cotton fibres, tightly woven so that they are smooth enough to leave the required shine while effortlessly absorbing any excess moisture. The base of the glass, whatever its shape, should be held in the corner of one end of the cloth while its bowl is polished inside and out with the fingers of the other hand in the other end of the cloth. If the glass is large, use two cloths, one in each hand.

There is one exception to the spotless glass rule, though it pains me terribly to say. Glasses for sparkling wine actually profit from a spot of dirt to give the carbon dioxide dissolved in the liquid something to nucleate onto and thus be released as gas. Bubbles will rise one above another from this nucleation point, this stream of bubbles being known as the perlage, so I don’t polish the very bottom of glasses I’m using for fizz for this very reason. The sides and the rim, of course, get a very good buffing.

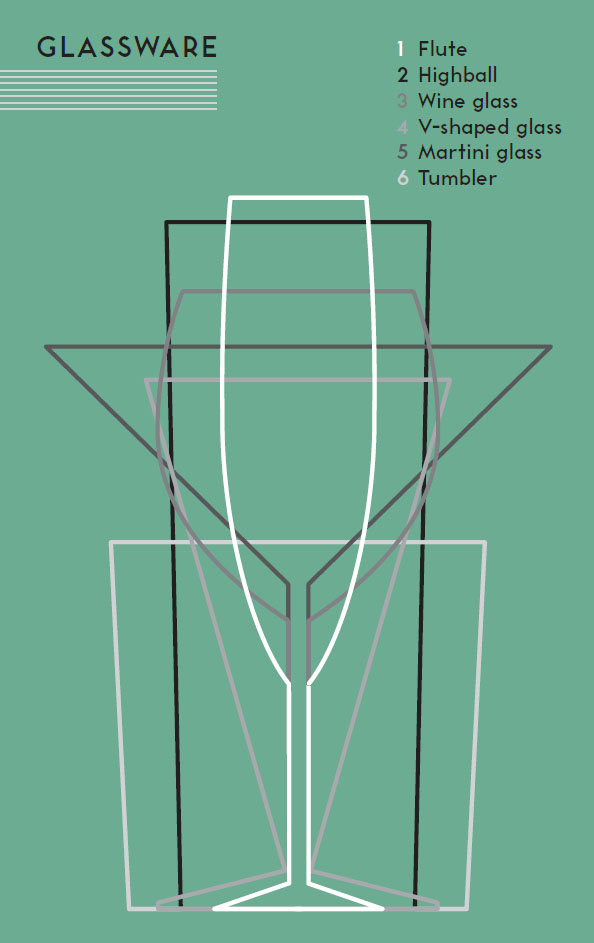

GLASSWARE ESSENTIALS

These are the six basic glass shapes that I usually have to hand to get me through the full gamut of aperitif situations. It is something of a luxury to have so many; if I had to choose just one it would be a decent-sized wine glass, in which no drink can go far wrong.

High-balls/hi-balls,Collins glasses

Tall glasses that suit long mixed drinks such as gins and tonic. Some flare out towards the top but I prefer the elegance of those with straight sides, whose slim shape means you can hold them with just the tip of the thumb and one or two fingers, so keeping the glass and its contents as cool as possible, while their narrow mouth keeps the bubbles in place.

Flutes

Synonymous with fizz. Tall, slim and elegant, like the most chic guest at a summer wedding, they hold the bubbles in sparkling wine well, while their narrow mouth concentrates the aromas and the long stem allows you to hold the glass without warming the wine. But drinking fizz from normal wine glasses is fine as well, as long as it’s not filled up too far – to one-third and no more; the aromas gather in the space between the top of the wine and the top of the glass, so these are the best choice if you’re drinking fizz with any complexity.

Coupes

These saucer-shaped stemmed glasses (supposedly modelled on Marie Antoinette’s breasts, or was it Louis XV’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour? Citations vary, but who cares? It’s a good story) have a certain louche, fur-coat- and-no-knickers retro charm. They are redolent of the days when racing drivers and footballers drank, smoked and shagged with as much enthusiasm and practised skill as they displayed in their sport; when they would be photographed pouring costly champagne to cascade over a tower of coupes in a disco-filled nightclub, a pretty girl on each side and a twinkle in each eye.

Coupes also hark back to the Jazz Age, of flappers with sharp bobs and red lips shaped like bows, their beaus in bold blazers and boaters. They certainly make me come over a bit Sally Bowles when they contain a straight-up cocktail (‘Divine decadence, darling’) but they fall short when it comes to anything fizzy because their wide mouth and shallow shape mean the bubbles disappear very quickly along with the aromas, so much of the fizz and flavour are lost. A cocktail such as a Gin and It is where it’s at in a coupe, or any well-chilled cocktail served straight up – in other words, with no added ice.

Tumblers, rocks and Old Fashioned glasses

Short, squat and without a stem, tumblers are thought to be so called because originally, stemless drinking vessels had slightly curved bases so they’d roll a little when placed on a surface, in danger of spilling the drink they contained. These days they tend to be flat-bottomed so are rather safer, and can be used for anything served neat or over ice, with or without a mixer. I use small ones for sips of something straight; larger ones if ice is involved.

Wine glasses

Or ‘stemware’, as we are supposed to call them. I’m all for drinking rustic vino out of a school-dinner tumbler, especially if one’s rolling in the grass at a sun-kissed picnic, or necking vin de sous la table in a Marseillaise backstreet, but if the wine is anything more than a notch above your average plonkage it really deserves a stem. Wine pros can get quite neurotic about the precise contours of the glass – the bulbous/slender Bordeaux/Burgundy shapes that supposedly make the wine hit the back/front of the tongue first, so allowing us to best appreciate the full-bodied/delicate nature of the wines, for example – but let’s not get distracted by such geekery here. A wine glass should simply be large enough to hold enough wine to enjoy with enough room left over (at least two-thirds) to maximise the swirling/sniffing/ooh-look-at-those-lovely-legs potential. If the sides curve in slightly towards the rim, so much the better. The legs, by the way, are the clear streaks that appear on the inside of the glass, formed as the liquid drips down and the alcohol begins to evaporate from it.

Cocktail glasses

V-shaped glasses with stems, also known as Martini glasses, are best known for housing Martinis and other straight-up cocktails. Elegant, with pleasing lines reminiscent of the art deco aesthetic, cocktail glasses definitely have a place in the keen drinker’s armoury, but I have to admit I rarely use them at home. It is another matter altogether in a decent cocktail bar; here they are positively essential. Suffice to say, if your Martini (or other straight-up drink) is not served in a chilled glass, you should move on forthwith; if your half-drunk Martini is transferred to a freshly chilled glass without your noticing, you should tip the bartender handsomely and ask him or her to marry you. This is the kind of attention to detail that marks the great bars from the merely good.

I’m also very partial to V-shaped cocktail glasses without a stem; they’re very chic and have the added advantage of being less easily knocked over in situations of extreme merriment.

A word on ‘novelty’ vessels for your drinks: jam jars are bad enough, but I’ve also seen drinks served in wellington boots, flowerpots, plastic buckets, tin cans and even (shoot me now) dog food bowls. Just stop.

STRAWS

I blow a bit hot and cold over straws. They caused me no end of joy when I was a child and delighted so in blowing down those twisted candy-stripe paper straws to make my drink bubble in a vaguely suggestive fashion, at least until the straw began to disintegrate and ended up a soggy, useless mess.

Although there is some evidence that drinking through a straw makes you drunk more quickly – the vacuum created when you suck makes the boiling point of alcohol drop, and the vapours created are absorbed into the bloodstream more quickly than when the alcohol in liquid form is absorbed through the stomach – this is not a good reason to adopt straws willy-nilly.

But straws sometimes have their uses: they also serve as stirrers so they often suit a tall drink involving a mixer, and they do away with the danger of the annoying collision between ice cube and nose that may occur. They are also useful for lipstick wearers, for obvious reasons.

Modern plastic straws are virtually indestructible and cause no end of damage to the planet, so use them judiciously. For this reason it is pleasing to see the revival of biodegradable paper straws, more robust than the straws of yore, but they’ll still go floppy if you’re drinking too slowly. Reusable straws made from stainless steel or other metals are now making an appearance but I’m not keen; metal-on-teeth is an unappetising clash and the metallic taste is impossible to ignore. Bamboo straws may well be the future: they have an eco-warrior worthiness but are relatively neutral in the mouth, and I’ve heard some bars are starting to grow their own.

Ice is important in so many aperitifs – an iceless G&T is quite unthinkable – but in fact it’s a relatively recent addition to the European drinking culture.

Aperitifs such as vermouths and other fortified wines would have been drunk au naturel in the places they were made, at least until the early years of the 20th century. It was the Americans who first championed ice in drinks by cutting enormous blocks of ice from the frozen wastes of the northern states in the winter and lugging them to the hot and thirsty islands of the Caribbean. By the end of the 19th century machines for making ice were churning out chunks to chill the cocktails enjoyed in America from coast to coast, but the Europeans took a little longer to embrace it. There are several good reasons for the G&T – or anything else involving a fizzy mixer – to be well iced. The jolly clunking of the ice in the glass is just one of them; more scientifically, the lower the temperature, the harder it is for the carbon dioxide dissolved in the drink to escape in the form of bubbles, so the drink will stay fizzy for longer.

Ice obviously chills a drink and also dilutes it to some extent. Somewhat counterintuitively, the more ice you add, the less it will dilute the drink because it keeps the volume of the liquid colder so the ice melts more slowly. Geeky cocktail bars often make their own ice, going to great lengths to eliminate impurities in the water by freezing it very slowly to produce crystal-clear blocks of ice that they carve into chunky blocks or sticks. There’s no need to be this obsessive at home, although it’s worth seeking out ice that comes in large solid cubes without indentations. For those who like a bit of nerdery, you can buy moulds to create ice globes nearly as big as tennis balls that are pleasing to use for something in a tumbler; a friend uses silicone muffin tins to achieve the same effect.

Crushed ice is nice in certain drinks but it melts quickly and is a such a faff to make at home (wrap cubes in a tea towel and bash with a rolling pin, or use one of those handle-operated crushers) that I rarely bother.

SODA

Soda water is carbonated water and appears in so many long drinks it deserves a small mention. Sparkling mineral water will do instead, though beware those like Badoit whose salty taste could mar other flavours in your drink. Soda water’s job is to be fizzy; don’t be tempted to use anything that’s gone a bit flat. I swear by my SodaStream machine for quality on-tap bubbles: not only does it work out in the long run far cheaper than buying endless bottles, it also cuts out all that worrying plastic waste. The whales will thank you for it in the end.

Tonic water plays a critical part in any aperitif drinker’s armoury; integral to a G&T of course, but so fitting with many other things besides. What sets tonic apart from other fizzy mixers is its defining ingredient, quinine. Known for its antimalarial properties, quinine comes from the bark of the cinchona tree and is terribly bitter when taken alone. Schweppes launched its quinine-based Indian Tonic Water in 1870, inspired by British officers in the days of the Raj who mixed their medicinal quinine with sugar, water and a hefty slug of gin. It is this underlying bitterness that makes tonic such a perfect mixer for vermouths and other similar aperitifs, stimulating the taste buds not deadening them with too much sweetness.

Until not long ago, Schweppes or cheap own-label tonics were pretty much all the choice we had; then Fever Tree arrived and has become a global phenomenon. More recently a slew of ‘artisan’ tonics have hit the market, many making much of their ‘natural’ ingredients; some flavoured with all sorts of other things as well as quinine. I, along with many professional boozehounds I know, still prefer Schweppes over others, especially their new ‘1783’ range of premium tonics that have done away with artificial sweeteners. I have researched this extensively and have come to the conclusion that the quality of the bubbles is as important as the taste. Schweppes’ bubbles are small and tight so give the best fizz on the tongue, but there are plenty of drinkers out there who’d disagree with me, so who am I to preach?

MEASUREMENTS

Proportions are more important than quantities when mixing a drink. Most bars serve 25ml or 35ml as a single measure for spirits, using a metal measuring cup called a jigger. It’s a useful tool for any serious drinker, though a modestly sized egg cup would do at a pinch. If I’m drinking just one spirit with a non-alcoholic mixer, anything less than 50ml/2oz generally seems to be missing the point; in the case of cocktails with several ingredients – Negronis spring to mind – those measures can amount to a hefty thwack of hooch which may not always be entirely sensible. I often use the cap of the bottle – around 10ml – to deliver a drink with the right balance that won’t make me fall over.

With aperitifs containing less alcohol – fortified wines and their various cousins – I favour something around 75ml/3oz as a decent amount if I’m drinking it alone, perhaps somewhat less if it’s mixed with other things, but it all depends on time, place and current mood.

Measuring individual drinks can be a bit fiddly if you’re making more than just a few; you can pre-mix pretty much anything as long as it doesn’t have a fizzy mixer or fresh ingredients that might go manky. Sling the ingredients into a jug, then pour into an old wine bottle (or bottles) and keep in the fridge until you’re ready to drink. Top tip if you’re having a party.

GARNISHES

I’m not a fan of outlandish and unnecessary garnishes; whatever is there should be doing a job beyond its appearance. Citrus fruits so often suit – as a slice or a wedge if you want some juice, or a strip of the skin (without any of the bitter white pith beneath it) for the concentrated zest of its oils. Whichever you use, squeeze it slightly as you drop it into the glass to release its magic. I’m sometimes partial to a sprig of a herb, most often mint, rosemary, basil or thyme, and I like cucumber sliced very fine with a vegetable peeler in some drinks if the weather’s warm. My fridge usually has jars of green olives, cocktail onions and griotte cherries; they’re nice to have about me but, to be honest, I could live without them if I had to. For me, aperitifs should speak of themselves and do not need anything else too outré to shine.

A FEW OF MY FAVOURITE THINGS...

It will come as no surprise that I have drunk too many aperitifs in my time to remember them all. In my selfless research for this book, however, I have kept a meticulous record. A few horrors stand out that I’d rather forget; others were perfectly pleasant but I’d probably give them the cold shoulder if our paths crossed again. Below is a list of some classic brands that can never put a foot wrong when used in the right context, as well as newer discoveries that particularly caught my fancy. The list is, of course, by no means exhaustive. I urge you to experiment and see what suits you best. If you really don’t like a bottle you’ve bought, use it for cooking in place of wine and continue to search for one that you do.

ITALY

Bèrto

Bonmè

Campari

Carpano Antica Formula

Cinzano

Cocchi

Cynar

Del Professore

Martini & Rossi

Mauro Vergano

Punt e Mes

Luigi Spurtino

SPAIN

Barbadillo

Casa Mariol

El Bandarra

Fernando de Castilla

Gonzalez Byass

La Luna

Lacuesta

Lustau

St Petroni

FRANCE

Byrrh

Dolin

Dubonnet

Lillet

Mattei Cap Corsa

Noilly Prat

Rinquinquin

Suze

SOUTH AFRICA

Caperitif

UK

Asterley Bros

Blackdown Silver Birch

Sacred

USA

Ransom

Sutton Cellars

Vya

AUSTRALIA

Regal Rogue

GERMANY

Belsazar

Ferdinand’s

Mondino