Chapter 15

May Day

“Hurry up!” Sophie was waiting for Rose by the front door. “The parade will be over before we get there!”

“Hold your horses!” Rose hurried to the tiny hallway, grabbed her coat, and fastened her hat with a pin.

Sophie teased, “I bet you want to look nice for that good-looking Ben.”

Rose shrugged. “Oh, him. He’s just a kid.” She smiled like a cat that had swallowed a canary.

“He’s older than you!”

Rose pushed her sister gently out the door. “Yeah. But I’m smarter than him.”

“Girls!” Mama called. “Be sure you dress warmly. It’s not summer yet!”

Mama had decided to stay home. Although she got around pretty well now that the cast was off her ankle, she still couldn’t stand for long periods of time. Besides, starting on Monday, she had a job working at the hospital, and she didn’t want to strain herself. Besides, she was busy preparing a “nice Friday night dinner.” (With Mama there were always a lot of “besides.”)

The strike was over! Sophie could hardly believe it, but it was truly, completely over! The week before, the union had signed four more contracts with employers; a hundred more workers had gone back to work.

Although some workers still hadn’t signed new contracts, as far as Sophie could see, the strike had fizzled out. The workers were ready to go back, contract or no contract. On Monday the rest of them would finally stop marching and return to work.

Had they won or lost? Sophie wasn’t sure. Some people said they had won because they had shown the owners that they wouldn’t give in. They had stayed on the picket line for ten long weeks. They had suffered cold and hunger, boredom and abuse. Dozens of workers had been arrested. Many of them had been harassed by those so-called private detectives. The workers had watched the police ignore this brutality and instead guard the strike-breakers. But the strikers had stood their ground.

In the end, they had gained only part of what they wanted, and the owners probably wouldn’t honor the contracts anyway.

Maybe other workers would be more successful in the future, and this strike had prepared the road ahead. And that was something.

Sophie and Rose lived in a flat on the second floor of a row house like this one in present-day Toronto.

The best news of all was that, with Mama and Rose working, Sophie could go back to school in the fall. She longed to finish high school and then go on to university. Maybe, just maybe, she could follow her dream to become a teacher.

She wasn’t the same person she had been at the end of February when the strike began. She wasn’t a naive kid anymore, but someone who had taken responsibility for her actions. She had stood up for herself, and for others as well.

✂

The weather was cool but sunny on that May Day, and Sophie was enjoying the sunshine. She was sick and tired of the awful winter they’d gone through, fed up with always feeling cold, with slogging through slushy puddles, with the biting wind blowing on her chapped face.

The union met at the Lyceum and then lined up for the parade. Each group marched along Spadina behind its banner: the Labor Zionists, the Workmen’s Circle, youth groups, schools, sports groups, and so on. At the rear walked some older men, their coat pockets bulging with newspapers, their heads together in discussions, their hands waving in the air to emphasize the points they were making. As they marched, bands played “The Internationale,” and regular marches like Sophie’s favorite, the “Colonel Bogey March.”

The parade stopped at Bellevue Square Park, near Kensington Market. The crowd milled around a portable stage that had been set up. There were songs and speeches, but the highlight of the day came when Emma Goldman walked onto the stage. Sophie had heard a lot of talk about Goldman, but this was the first time she’d ever seen her.

She was a short, sturdily built woman, with brown hair pulled back in a bun and round glasses resting on a smallish nose. She looked briefly at her notes and then gazed out at the audience. The crowd quieted down. Sophie could even hear birds singing and the muffled sounds of traffic on Spadina.

“My friends,” Goldman said in a clear, ringing voice. “Many of you have just finished a long, drawn-out strike. In these hard times, you stood up for what you believed. You fought for shorter hours, for safer working conditions, and most of all, you fought for your union.”

“Hooray for the ILGWU!” Ethel shouted.

“Hip hip hooray! Hip hip hooray! Hip hip hooray!” the crowd answered.

Goldman held up her hand. Some stray hairs had escaped from her bun and she brushed them aside. “Believe me,” she continued, “my heart goes out to you who have suffered for a cause. I know what it feels like to work in a sweatshop for ten or twelve hours a day. I know what it means to stand up for your beliefs and to be punished as a consequence.”

Morris the Presser, who was standing behind Sophie, whispered, “She was put in prison, you know.”

Herman the Cutter said, “Yeah, I know. For two years.”

Sophie glanced at Rose, and saw that her face was pale and drawn. “Quiet, please,” she whispered to the two men.

“Sorry,” they muttered.

Goldman continued. “You fought for all those things, but most of all, you fought for your dignity, so you could make a living wage.” She sighed. “We all have the right to earn a living—men and women. We know full well that, in the factories, women are often treated like second-class workers. They earn only a fraction of the pay for the same job men do.” She smiled wearily. “This may sound like a revolutionary idea—of which, you know, I have many—”

“You sure do!” Sadie shouted.

“Pipe down!” Morris yelled.

“But I say today, it is only fair that women receive equal pay for equal work. Only in that way can a woman become independent. Only in that way will she be able to support herself.”

“I want to be independent like that!” Sophie whispered.

Rose nodded. “Me too!”

Goldman leaned toward the audience. “There is one more point I wish to make today. If a woman cannot support herself, she is often forced to resort to a life of crime. I tell you, the criminal justice system is broken.”

Rose shivered. Sophie put her arm around her sister’s shoulders.

“Year after year, prisons return to the world a shipwrecked crew of humanity, their hopes crushed. With nothing but hunger and inhumanity to greet them, these victims soon sink back into crime as the only possibility of existence.”

Rose leaned over and whispered in Sophie’s ear, “I saw a lot of women like that in jail.”

“Do you want to talk about it?”

“Later. I’ll tell you all about it later.”

Goldman straightened her back and counted on her fingers. “Three things I abhor above all: ignorance, superstition, and bigotry. These I will fight to the bitter end.”

The crowd cheered and clapped. Goldman smiled and waited until they had quieted down. “My friends, every daring attempt to make a great change in existing conditions has been labeled Utopian. But we must continue to fight for our beliefs, and for what is right! And together, we shall overcome!”

After her speech was over, there was a brief question-and-answer period. Sophie felt glued to the spot. She wanted to ask a question but felt overcome with shyness. Goldman left the stage, and Bernard Shane and other union organizers crowded around her.

Sophie took a big breath, and pulled Rose toward the front. “Come on, Rose. I want to talk to her.”

Labor activist Emma Goldman fought for the rights of women garment workers.

“To Emma Goldman? Are you kidding?”

“Come on!”

“Not me. You go ahead.” Rose smiled. “I want to talk to Ben. Meet me at United Bakers in half an hour?”

The memory of sitting with Jake at United Bakers flashed through Sophie’s mind. “No, not there. Let’s meet at Walerstein’s.”

Rose shrugged. “Okay. Sure.”

Sophie made her way through the laughing, milling crowd. She edged closer to Goldman and gathered her courage. “Miss Goldman?”

Goldman turned toward her and gazed at her with clear, blue-gray eyes. “Yes, my dear?”

“My name is Sophie Abramson.”

“Were you one of the strikers?”

Sophie swallowed hard. “To the very end.”

Goldman held out her hand and shook Sophie’s. “You were very brave to stand up to the owners.” She smiled at Sophie and her serious face seemed transformed, as if a ray of sunshine had come out from behind a cloud. “The world will need young women like you to lead the fight against tyranny and oppression.”

Sophie blushed. “Can I really do that? I mean, fight against all that evil?”

Goldman put her hand on Sophie’s shoulder. “You can if you are determined to. And Sophie?”

“Yes?”

“One of the weapons you will need is an education.” Goldman sighed. “I myself had to leave school early and could not go to high school.” She shook her head. “ You know, my father once told me, ‘Girls do not have to learn much. All a Jewish daughter needs to know is how to prepare gefilte fish, cut noodles fine, and give the man plenty of children.’” She squared her shoulders. “What I know, I learned for myself.

“Go back to school, Sophie Abramson. Read and study. Then you will be ready to fight whatever battles lie ahead.” She placed her hand on Sophie’s shoulder. “Will you do that, my dear?”

“I will, Miss Goldman. I will!”

✂

The girls sat at a small table at Walerstein’s, an ice-cream soda in front of each of them. The store was crowded with other people who had come from the parade. They jostled for chairs around the tables or sat on stools at the counter, greeted each other, shared pamphlets they had picked up, and talked about Goldman’s speech.

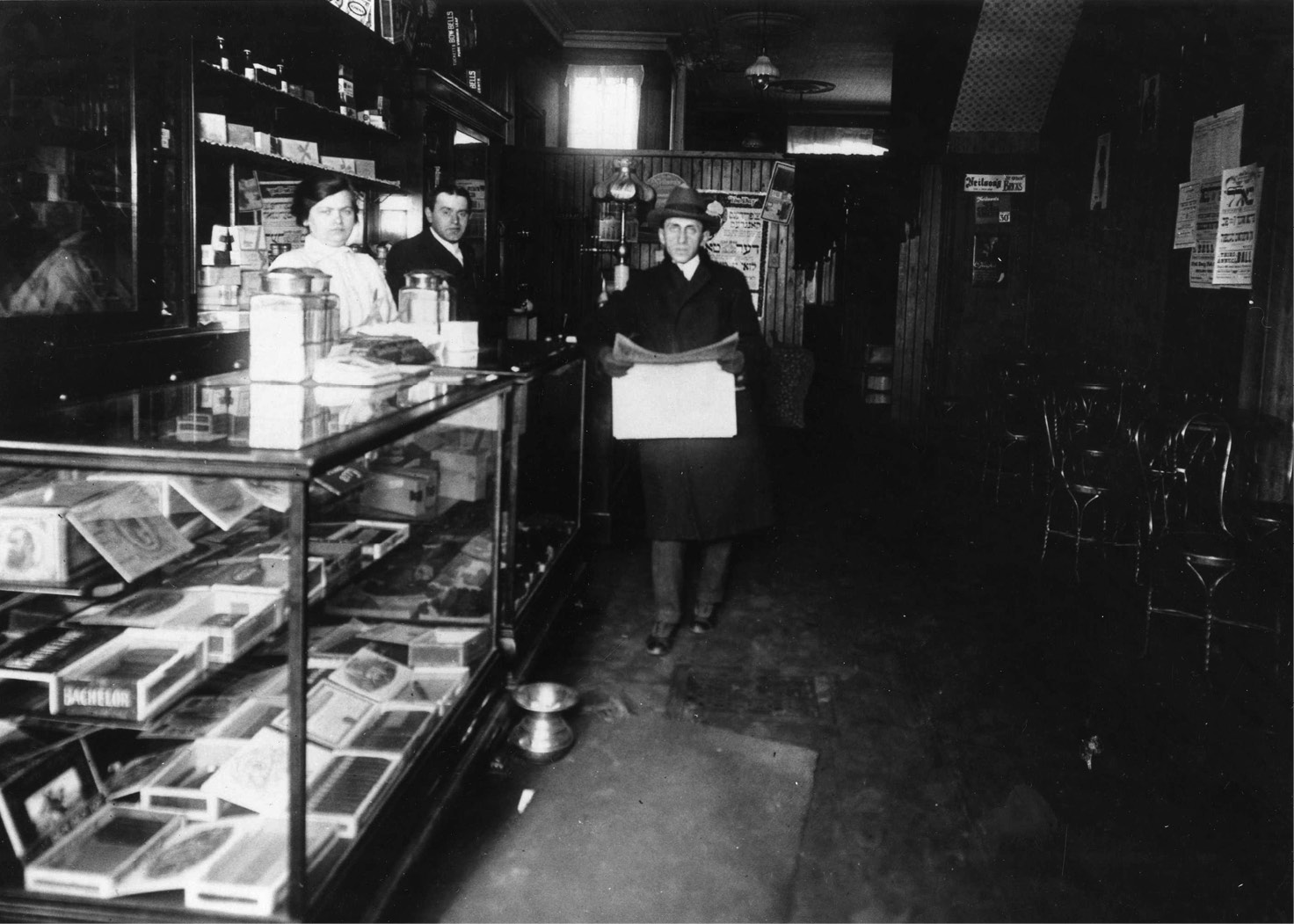

Walerstein’s Ice Cream Parlour on Spadina Avenue was a popular spot for meeting friends.

Sophie sipped the soda slowly and tried to make it last as long as possible. “You said you’d talk to me later.” She raised her chin. “Well, later is now.”

Rose sighed and reached for her sister’s hand. She related what had happened to her at the Mercer. Sophie knew she wasn’t telling her everything, but she let it go. For the first time, the very first time, Rose was treating her as an equal.

“But that’s all water under the bridge now.” Rose wiped the tears from her eyes. “This strike was only the beginning. And, little sister, we’ve got a lot more fight in us yet!”

“We tried to make a great change. Didn’t we, Rose?”

“Of course we did! And we’ll keep trying!”

“Even if we couldn’t change everything?”

Rose put her hand on Sophie’s. “Even if we couldn’t change everything.”

“Do you remember how we used to come here with Papa?”

Rose nodded. “He used to stir a heaping teaspoon of sugar into his tea, and then another.”

“Yeah. I think he still had the mud of the Old Country on his shoes,” Sophie said.

“He’d look at us with a twinkle in his eye. And he’d say, ‘My darling daughters, the Golden Land this is not.’”

Sophie smiled at her sister. “On the other hand…”

“On the other hand, it’s not so bad.”