The importance of developing effective tourism distribution systems has been increasingly recognized in recent years, both in the tourism literature and by the tourism industry. As with other emerging areas of research, the literature on tourism distribution is at present rather fragmented and studies are partial in scope, providing researchers with considerable opportunities and challenges to develop this field further. This paper reports on a major five-year publicly funded project entitled ‘Innovation in New Zealand tourism through improved distribution channels’ that seeks to address many of these challenges and discusses some of the broader issues that have arisen. Begun in 2002, the project seeks to examine systematically different types of distribution channels, to identify the factors that influence the behaviour and motivations of all channel members, to assess the extent to which different channel structures, practices and relationships influence yield, and to recommend best channel management practices for different markets, regions and forms of tourism (Pearce, 2003).

After the origins of the project are outlined the research design and methodology are discussed, emphasizing a variety of issues associated with large-scale projects. The diverse literatures to which different aspects of distribution channels might be linked are then presented before the general patterns emerging from the results obtained to date are summarized and avenues for future research on tourism distribution are indicated.

Three sets of inter-related factors gave rise to this project and to the approach adopted: an academic interest in tourism distribution, industry applications and funding regime considerations.

Firstly, the benefits of an integrated approach to the analysis of interdependent channel members was highlighted in a study of New Zealand outbound travel to Samoa (Pearce, 2002a). In particular, that study identified the scope for distribution channels to constitute ‘a potentially powerful unifying force by bringing together markets and destinations and by stressing inter-sectoral linkages’ (Pearce, 2002b, p. 15). That potential lies in the role which distribution plays in providing ‘the link between the producers of tourism services and their customers’ (Gartner and Bachri, 1994, p. 164), in serving as the bridge between supply and demand (del Alcázar Martínez, 2002). Such a bridge is especially important given the fragmented nature of much tourism research, where the emphasis is frequently on only one part of a dichotomy (supply or demand, production or consumption, origins or destinations) and where tourism industry related research is notably bereft of unifying concepts and theories (Pearce, 2004).

This broader integrative role of distribution research complements the increased recognition of this part of the marketing mix in its own right, as evidenced by a growing literature on the topic (del Alcázar Martínez, 2002; Buhalis and Laws, 2001; O’Connor, 1999) and by a more explicit acknowledgement of its competitive importance. In this latter regard, Kotler et al. (1996, p. 451) assert that ‘a well-managed distribution system can make the difference between a market share leader and a company struggling for survival’ while Buhalis (2000, p. 111) argues distribution is ‘one of the few remaining sources of real competitive advantage’.

In New Zealand the need for research of an applied nature was underlined in the New Zealand Tourism Strategy 2010. Recommendation 21 of that strategy highlighted the need to ‘develop a tourism distribution channel strategy so New Zealand operators have an increased level of influence in the distribution channel’ in order to achieve the goal of marketing and managing a world-class visitor experience (Tourism Strategy Group, 2001, p. 41). This requires an increased understanding of the structure and functioning of existing channels. While there may be a good appreciation of the issues by the national tourism marketing body and by some of the larger companies, this understanding is not always found across the industry. This was borne out in the early stages of the research when one of the more established heritage managers interviewed commented with regard to distribution channels: ‘Probably the biggest minus is trying to work it all out… I just feel it should not have to be that complicated’ (Pearce and Tan, 2004, p. 235).

Much of the complication in the case of New Zealand lies in the distinctive nature of tourism in that country where much international tourism is characterized by circuit travel, involving multiple arrangements and transactions across different sectors in several destinations, commonly in both the North and South Islands. Moreover, a large degree of independent travel occurs amongst both domestic and international visitors (Pearce and Schott, 2005; Stuart et al., 2005). These factors combine to generate a different set of distribution issues than those involving packaged, resort-based travel, the focus of much of the distribution channel research in Europe and elsewhere (del Alcázar Martínez, 2002; Buhalis and Laws, 2001). As a result, applied research in New Zealand has the potential to contribute to a more general understanding of tourism distribution through the different research questions that arise there.

Finally, the nature and scale of the research have been influenced and made possible by the prevailing research-funding regime. The Foundation for Research Science and Technology, which administers the Public Good Science Fund, has encouraged large-scale, multi-year project applications, emphasizing the public good nature of the outputs and end-user uptake of results. This regime has both enabled a larger, more comprehensive approach to the analysis of distribution channels and contributed to the academic and applied nature of the research. In terms of scale, the project analyses the full range of channel members, involves primary data collection in selected locations throughout New Zealand and in five overseas markets, is being undertaken by a team consisting of 1.6 FTE (full-time equivalent) staff, three Master’s students and short-term research assistants, and has a budget of $320,000 p.a. over five years. The project is also characterized by the goals of disseminating results to diverse audiences and has a significant human capacity development component through the incorporation of young researchers.

The scale of the project has enabled a comprehensive, systematic, multi-stage approach to be adopted. This approach seeks firstly to establish a detailed analytical framework for systematically identifying different types of distribution systems and classifying all members in the channel. Particular emphasis here is being given to identifying different types of channel structure, taking a whole systems approach that incorporates all channel members. This is an ambitious undertaking and contrasts with much of the earlier empirical work that often involved a two-stage or business-to-business approach rather than an analysis of entire distribution channels. The need for a more holistic approach is inherent in Kotler et al.’s (1996, p. 483) definition of a distribution channel as: ‘A set of interdependent organizations involved in the process of making a product or service available for use or consumption by the consumer or business user.’ The notion of ‘a set of interdependent organizations’ underlines the need to examine the structure of the entire set of organizations and channel members (including the consumers) and to analyse the nature of the interdependency manifested in the relationships between them. Similarly, Bitner and Booms (1982, p. 40) argued: ‘Each intermediary has the power to influence when, where and how people travel.’ Again, the implication is that a full understanding of the distribution channels for any destination, market or product will only result from a more systematic and comprehensive approach that takes account of the role and behaviour of each of the channel members.

Secondly, the project seeks to identify the factors that influence the behaviour and motivations of the channel members which determine the nature and strength of the relationships between them and which lead to cooperation or conflict in the channel. The importance of this behavioural component was stressed by Bitner and Booms (1982, p. 40), who noted: ‘While structural factors give clues to how the system operates, motivational and behavioural factors provide more complex explanations for why intermediaries do what they do, what influences their decisions, and how they interact with customers and suppliers.’ In this project, this search for understanding what factors influence behaviour is being extended beyond the intermediaries to include all channel members, including providers and consumers. This point was well made in the seminal work by Wahab, et al. (1976), who recognized that different channel members have different interests.

Thirdly, an attempt is being made to assess the extent to which different channel structures, practices and relationships impact on tourism growth and influence yield for different channel members and to evaluate the cost effectiveness of different forms of distribution systems. Given that tourism businesses are faced with selecting a single or multiple channels from a range of distribution structures, systematically being able to evaluate the options available becomes a crucial part of an effective distribution strategy. To date, few tools for doing this are available.

Finally, recommendations will be made on best channel management practices for different markets, regions and forms of tourism and guidelines for these disseminated to a wide range of end users.

In order to allow different types of structure and behaviour to be examined while at the same time keeping the project manageable, this multi-stage design is being applied to selected destinations, markets, intermediaries, sectors and forms of tourism.

From an analytical point of view a destination perspective holds much potential for developing typologies (Pearce and Tan, 2002). In particular, adopting a sub-national destination perspective highlights the need to move beyond the analysis of only a single set of suppliers in order to examine channel structures associated with all sectors (e.g. attractions, accommodation, transport) and players (e.g. large and small businesses) and to investigate the ways in which these come together. A destination perspective also provides scope for the analysis of the interplay of the promotion and distribution of individual products and services versus the destination as a whole and for the examination of the role of destination characteristics in the formation of channel structures. Examples of three contrasting types of destination have been chosen to extend the range of possible channel structures and to examine differences in the impact of destination characteristics:

In the same way that different channel structures and behavioural factors were expected to vary across destinations, it was assumed that differences would occur from market to market. Accordingly, and following discussions with industry representatives, a selection of international markets was chosen taking into account factors such as the size and maturity of the markets, distance from the destination and cultural factors. These are:

Distribution to the domestic market is being studied by including New Zealand visitors in destination-based surveys in Wellington and Rotorua and by focusing on supplier practices to reach the New Zealand market in the destination case studies.

In addition to the intermediaries located in the above markets – for example wholesalers, direct sellers and retail travel agencies in the United Kingdom – New Zealand-based intermediaries are also being interviewed. These are primarily inbound tour operators, travel management companies and professional conference organizers.

Research is being concentrated on five main sectors: accommodation, attractions, transport, conferences and events. In the first of these two sectors the focus is on a range of providers in the focal destinations. Thus a selection of accommodation providers has been included in Wellington, Rotorua and Southland, ranging from large chain hotels to small independent bed and breakfast establishments. Likewise, a range of different types of attractions is being studied, with a particular emphasis on heritage and cultural attractions (Pearce and Tan, 2004). Conferences and events in Wellington were added to the project following the initial stages of the destination-based studies that revealed specific channels for these sectors characterized by quite intense activity of a short-term duration (Smith, 2004). In addition, a more specific examination of distribution channels for adventure tourism, a significant and growing sector in New Zealand, is being carried out, drawing on examples from Queenstown. A nationwide perspective has been adopted in the case of the transport sector whose role is essentially to link different places in a range of networks or circuits, an important consideration given the itinerant nature of much international tourism in New Zealand.

Particular attention is being paid throughout the project to identifying differences in the distribution channels for independent and packaged travel. The latter has attracted the most attention in the international literature to date, given the emphasis there on travel to mass resort destinations. Packages are also a dominant form of travel from some major markets to New Zealand but independent travel is also very significant, not only for domestic tourists but also for some key overseas markets such as Australia and the United Kingdom. As most tourist businesses in New Zealand depend on a mix of independent and packaged clients, understanding any differences in distribution to these major segments was deemed at the outset as likely to be very important. This has since proved to be the case (Pearce and Tan, 2004). While the emphasis throughout is predominantly on leisure travel, special attention has also been given to corporate travel as more businesses are making special arrangements to manage their company travel (Garnham, 2005).

Comparative Analysis

Comparative analysis is another key feature of the overall research design. Systematically comparing distribution structures across the selected cases enables general characteristics to be distinguished from features specific to any one destination, market, sector or form of tourism (Pearce, 1993). Similarly, systematic comparison also allows for the transfer of experience between them and will facilitate the formulation of subsequent recommendations on best channel management practices. A major methodological challenge here is to collect and analyse data that not only allows examination of the structure and functioning of particular destinations, markets, sectors and forms of tourism but also enables comparison within and between these different dimensions. This has involved the use of multiple data collection methods and an integration of the different parts of the project.

In the first two phases of the project three main methods were used to collect and analyse the necessary information: in-depth structured interviews, surveys and the analysis of tour operator catalogues, websites and other documentary information. In-depth structured interviews constitute the main means of data collection from the suppliers and intermediaries. The interviews were structured around a checklist of questions which focus on the nature of each business, the markets targeted, the distribution channels used or, in the case of the intermediaries, their role in the distribution of New Zealand product, strategies followed, factors influencing these, relationships established and partnerships developed. This core of common questions provided the basis for comparability across the different cases and respondents but the format followed also allowed issues relating to particular businesses, destinations, markets or channel members to be explored. Key themes were followed throughout the various components of the project that will subsequently facilitate integration of the different facets. For example, the suppliers were asked to identify what factors influence their choice of distribution channels and the selection of channel partners that they work with. Subsequently, the various intermediaries – inbound operators, wholesalers, direct sellers, retail agents – were asked about their choice of suppliers and other distribution partners.

Similar issues have been explored in the visitor surveys that complement the in-depth interviews of suppliers and intermediaries. Some 1,000 visitors each in Rotorua and Wellington were surveyed on an intercept basis at selected sites in the two destinations during January 2003 (Pearce and Schott, 2005). The surveys focused on the visitors’ information search and buying behaviour with reference to how they travelled to the destination, the accommodation used and the activities undertaken. This enables the demand data to be compared systematically with the supply-side information in terms of the major themes of the project.

Further triangulation comes from an analysis of operator and wholesaler catalogues and from the websites of suppliers and intermediaries. The catalogues provide a reasonably concrete and comprehensive picture of the products and properties being offered in different destinations to the different markets, whether to groups or on an FIT basis (Pearce and Tan, 2006; Pearce et al., 2004). Similarly, the websites of the intermediaries constitute a basis for comparing the extent and coverage of product in the focal regions while those of the suppliers provide insights into how this channel is being used, for example as a means of providing information and/or enabling transactions (Tan and Pearce, 2004).

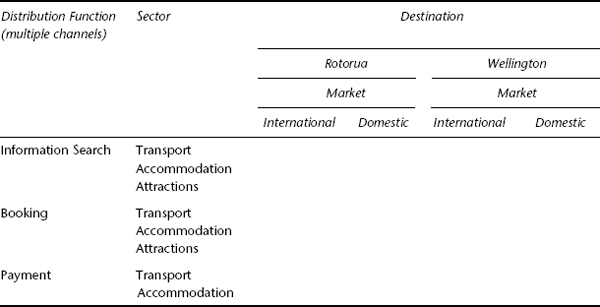

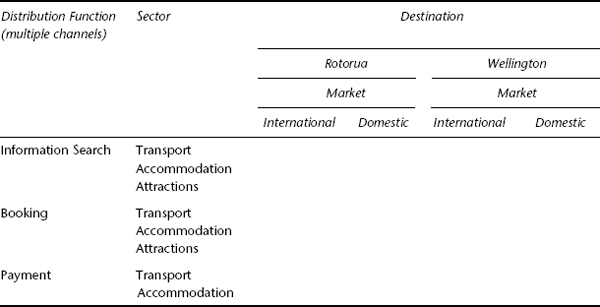

Table 4.1, representing the analytical framework for the visitor surveys in Wellington and Rotorua (Pearce and Schott, 2005), shows one way in which this comparative approach is being applied. The analysis follows the presumed sequence of distribution activities from the visitors’ perspective – information search, booking and purchase – for domestic and international visitors in the two destinations and across the three key sectors of accommodation, transport and attractions.

In other parts of the project a first level of analysis has occurred on a case-by-case basis, with papers being produced, for example, on distribution channels in Wellington (Pearce et al., 2004), Southland (Stuart et al., 2005) and Rotorua (Pearce and Tan, 2006) and theses being completed on distribution to the Indian and Japanese markets (Sharda, 2005; Taniguchi, 2005). The Wellington case study brings together the perspectives of the suppliers, intermediaries and visitors; that on Southland emphasizes sub-regional, sectoral and market segment differences within a peripheral region; and in the case of Rotorua the distribution mix for attractions is analysed in detail (Pearce and Tan, 2006). The Indian case study examines the characteristics of distribution in an emerging market; that on Japan stresses the more industrialized, integrated nature of distribution channels in that market. These case studies provide the scope to explore the different dimensions of distribution in depth; later, through the common core focus the channel structures and behaviour will be systematically compared across the destinations, markets and forms of tourism, with some provisional similarities and differences being highlighted below.

Sequencing the different facets of the overall project has required careful consideration. Beginning with the destination case studies has proved to be a useful point of departure, enabling issues to be identified and the methodology to be refined before tackling the more logistically demanding and resource-heavy market studies. Moreover, with these logistical and methodological points in mind, work began in each case on the nearest destination and market, respectively Wellington and Australia, before those further afield were undertaken. Originally it had been proposed to complete the structural analysis before examining the behavioural aspects of the different suppliers and intermediaries. In the event, these were undertaken conjointly within the same set of interviews as, in addition to significantly reducing travel costs, setting up appointments for a single interview with the targeted respondents proved sufficiently challenging without attempting a second.

Table 4.1 An analytical framework for examining the visitors’ perspective on tourism distribution channels

With these first two stages completed and a clearer picture of channel structure and behaviour having been established, attention is being focused on a small number of representative cases in order to tackle aspects of yield in a more targeted fashion and with much more informed knowledge of the multiple channels in use. This will involve a twofold approach. Firstly, visitors to individual attractions are being surveyed to establish the relative importance of the channels that they have used; the survey will be informed by earlier research on the visitors’ perspective carried out at the destination level (Pearce and Schott, 2005). Secondly, the cost effectiveness of the different channels being used by the providers in question is being analysed adapting techniques applied in the accommodation sector (Middleton and Clarke, 2001) but giving emphasis to the comparative analysis of returns from the multiple channels used. This phase is proving demanding due to the commercially sensitive nature of much of the data required and to difficulties relating to accessing information costs and revenue at the level of distinct distribution channels. Although challenging, this phase has been facilitated by the relationships established during the early phases of the project and by the feedback of provisional results to respondents, demonstrating that information useful to the industry can be generated and confidentiality has been respected.

As the project has progressed, the breadth of studies to which research on distribution channels might be linked has become increasingly wide-ranging. This issue is not of course specific to tourism distribution (Pearce, 2004) but the range of literatures to which such research might profitably be linked is a function both of the scale of this project and the integrative and multi-faceted nature of distribution channels. The tourism distribution literature, drawn together in recent books (del Alcázar Martínez, 2002; Buhalis and Laws, 2001; O’Connor, 1999), formed the core on which the initial phases of the project were based but as work has progressed on particular topics these have also been progressively cast in other more specific and hitherto largely non-convergent literatures in order to bring more understanding to the issues at hand. This process is depicted in Figure 4.1, where the core tourism distribution literature is intersected by more specific literatures relating to the case study contexts (e.g. urban tourism, tourism in peripheral areas), types of market, forms of tourism and particular fields of study (e.g. tourist behaviour, tourism and ICT, or information and communication technology). At present the emphasis is on the linkages between the core and the subsets in the outer ring, rather than between the outer literatures, though integration may occur here in the latter phases of the project as the different facets are brought together.

Linking the literatures in this fashion is enabling the distribution channels research to be advanced in a variety of ways. Consideration of the destination case studies in the context of these other literatures is proving a useful means of ‘breaking out of the case’ (Dann, 1999), of seeing the distribution issues in Wellington or Southland not just in terms of those places but respectively of cities and peripheral regions more generally (Pearce et al., 2004; Stuart et al., 2005). In this way it is hoped to develop a more generalized understanding of tourism distribution systems as well as to contribute to the literatures on urban tourism and peripheral regions, both of which have essentially neglected distribution issues to date. Distribution channels, for example, constitute a fundamental link between cores and peripheries and as such might usefully be added to the structural relationship approach to the study of peripheral regions (Stuart et al., 2005). Likewise, the analysis of distribution to the Indian market has been set not only in the context of emerging and mature tourism markets (Casarin, 2001; King and Choi, 1999) but also of emerging markets more generally (e.g. Arnold and Quelch, 1998). This has enabled the structures and behaviours found in the Indian market to be interpreted in a wider context, with the case demonstrating a number of similarities with broader aspects of emerging markets such as channel fragmentation, multilayering and a lack of stability (Sharda and Pearce, 2005).

Figure 4.1 Tourism distribution channels and inter-related literatures

In terms of visitor behaviour, the tourism distribution literature is hugely asymmetrical, emphasizing the role of other channel members, the providers and intermediaries, rather than the consumers (Pearce and Schott, 2005). Reference to the tourist behaviour literature shows the emphasis there is primarily on information search rather than on the other two main components of distribution, booking and purchase. By situating the analysis of the visitors’ use of distribution channels in these two literatures the research gap that this part of the project is attempting to fill can be demonstrated clearly and, to a limited extent, the results can be interpreted by reference to this earlier work.

While a full synthesis of the results must necessarily await completion of other aspects of the project, patterns are starting to emerge from the results that have been reported to date. Some commonalities can be identified but the general picture developing is that a differentiated approach must be taken to formulating effective distribution strategies, a differentiation that takes into account not only key market segments but also sectoral differences and contextual factors associated with particular types of destination and market. Moreover, describing channel structures is not enough; more emphasis must be given to behavioural factors in order to understand why channel members behave as they do and why they use particular channels or change these. In this respect, taking a whole systems approach provides greater insights and understanding, counterbalancing the increased methodological challenges and heavier resources needed.

The results from various parts of the study, for instance, highlight the different distribution issues and channel structures relating to packaged travel, especially that involving series tours, and independent or semi-independent travel. This reflects to a large degree the characteristics and needs of both consumers and suppliers. The Southland study showed distribution channels for businesses serving the group, special interest and semi-independent segments are generally more multilayered, make greater use of inbound tour operators (IBOs), wholesalers and retail travel agents, and have their products pre-purchased in the market, generally either as part of a group or a personalized package (Stuart et al., 2005). Businesses catering to independent travellers, on the other hand, tend to have a greater proportion of direct sales and employ a mix of en route and at destination strategies involving information and sales through other intermediaries, especially information centres and formal or informal networks of other providers. Similar patterns are found in Wellington but the urban tourism product appears less subject to the ‘bundling’ function typical of the distribution of mass tourism packages to resorts (Pearce et al., 2004). The analysis of the visitor surveys shows independent travellers are generally making a series of decisions about the purchase of individual products, often using multiple channels to collect all their information and make their different transactions (Pearce and Schott, 2005). While some of these results are not unexpected, the project is revealing the need to pay greater attention to distribution to various types of traveller, for the emphasis on packaged travel that has dominated much of the European literature (Casarin, 2001) tells only part of the overall story.

The scale and diversity of the project are also revealing important sectoral differences, drawing particular attention to issues associated with the distribution of attractions, a sector that has been subject to much less research than accommodation or transport but one whose distribution strategies are crucial to successful destination development. The visitor surveys, for example, show that independent travellers use different information sources to find out about transport, accommodation and attractions. Booking and advance purchase are far less common in this latter sector than in the other two (Pearce and Schott, 2005). Likewise, transport and attractions businesses tend to use the Internet differently as a distribution tool: with the former, online transactions have become commonplace; with the latter, the Internet is still used predominantly for information dissemination (Tan and Pearce, 2004). The detailed empirical examination of attractions in Rotorua has revealed a greater diversity in the distribution mix of attractions than is hinted at in the meagre textbook references, the proportion of direct sales ranging from 95 per cent to 20 per cent (Pearce and Tan, 2006). Factors influencing the overall distribution mix include the segments targeted, the characteristics of the attractions and the perceived advantages and disadvantages of different channels with respect to yield, control and seasonality. At the same time, some similarities are to be found between small accommodation providers and attractions operators, with both often being more reliant on direct sales and ‘at destination’ distribution than large hotels or major carriers (Pearce et al., 2004; Stuart et al., 2005).

The value of taking a whole systems approach, looking at distribution issues across all channel members, has also been confirmed by the additional insights being provided, by the differences being revealed at different channel layers and by the greater ability to cross-check behaviours of various channel members. In the case of the Indian market, for example, the fragmentation of the distribution channels, the heavy dependence on New Zealand-based inbound operators and the relative paucity of direct sales can be explained in terms of the characteristics of the market and of the varying needs and interests of the Indian intermediaries and suppliers (Sharda and Pearce, 2005). Lacking destination knowledge and travel experience, and faced with the complications that circuit travel in larger groups brings, many Indian travellers at present seek the ease and security of a high level of packaging carried out by the Indian intermediaries and the New Zealand IBOs. In turn, the small volume of Indian travellers to New Zealand and associated price issues explain the Indian intermediaries’ and the New Zealand suppliers’ dependence on the IBOs.

Differences are also found in the use of the Internet across the channel members: providers, especially in the transport sector, use it mainly for sales, whereas intermediaries are increasingly taking advantage of the medium for communication and for marketing, for example using e-shots (Tan and Pearce, 2004). Visitors use the Internet for booking transport more than they do accommodation, in part because online systems are less well adapted at present to immediately confirm rooms compared to seats (Pearce and Schott, 2005).

In the Wellington case study, bringing together the views of the suppliers, intermediaries and visitors has shown a certain amount of congruence in the practices, needs and interests of the different channel members. The visitor survey results, for example, confirm the importance of at destination distribution amongst the small accommodation and attractions providers but the study also raises the question of where responsibility lies for stimulating demand for travel to the city in the first place (Pearce et al., 2004). This integrated approach also showed how guidebooks, the most important source of information used by visitors to find out what there is to see and do in Wellington is also a channel over which the attractions providers have limited or no control while the interviews with intermediaries identified factors leading to the limited inclusion of Wellington in series tour itineraries.

Further synthesis along these lines is now being undertaken before aspects of yield are examined and the best management practice guidelines are drawn up. While many aspects of distribution will have been covered when the project is complete, considerable scope exists for many of the topics to be taken further and for the generality of the findings to be tested in other contexts. For example, the intermediaries’ dominance over distribution to peripheral regions appears to be far less critical in Southland where many of the businesses have some choice in who they target and which channels they use (Stuart et al., 2005) compared to the mass, packaged resort-based ‘sun, and sea’ tourism described by Buhalis (1999) in the Aegean. Clearly, all peripheral regions are not the same and similar work in other regions is needed to develop a more comprehensive picture of distribution issues there. Likewise with cultural tourism: parallel research in Catalonia has revealed many similarities with the New Zealand situation, particularly in terms of the prominence of direct sales to independent travellers, but differences do arise with group visitation due to contextual factors (Pearce, 2005). Group visitation to cultural attractions in Catalonia is dominated by excursionists from the coast, a feature which contrasts markedly with the far greater role of series tours in New Zealand where visits to cultural attractions are often part of a broader country-wide circuit and differing net rates may be offered depending on the volume of business generated by various operators (Pearce and Tan, 2004). Other aspects of distribution arising out of this study could now be developed elsewhere. The exploratory work on empirically measuring the distribution mix of attractions, for example, could be usefully extended to other sectors, while parallel research on other destination-market pairs would enable a better appreciation of distribution and market maturity. In these ways, it is hoped that the project will not only assist with developing more competitive distribution strategies in New Zealand but also, through the methodology developed and examples provided, it will make a contribution to an enhanced understanding of tourism distribution in general.

del Alcázar Martínez, B. (2002) Los Canales de Distribución en el Sector Turístico (Distribution channels in the tourism sector). Madrid: ESIC Editorial

Arnold, D. J. and Quelch, J. A. (1998) ‘New strategies in emerging markets’. MIT Sloan Management Review, 40(1), 7–20

Bitner, M. J. and Booms, B. H. (1982) ‘Trends in travel and tourism marketing: The changing structure of distribution channels’. Journal of Travel Research, 20(4), 39–44

Buhalis, D. (1999) ‘Tourism on the Greek Islands: Issues of peripherality, competitiveness and development’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1(5), 341–58

Buhalis, D. (2000) ‘Marketing the competitive destination of the future’. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116

Buhalis, D. and Laws, E. (eds) (2001) Tourism distribution channels: Practices, issues and transformations. London: Continuum

Casarin, F. (2001) ‘Tourism distribution channels in Europe: A comparative study’. In D. Buhalis and E. Laws (eds) Tourism distribution channels: Practices, issues and transformations. London: Continuum, pp. 137–50

Dann, G. M. S. (1999) ‘Theoretical issues for tourism’s future development: Identifying the agenda’. In D. G. Pearce and R. W. Butler (eds), Contemporary issues in tourism development. London: Routledge, pp. 13–30

Garnham, R. (2005) ‘Corporate travel agents: Channels of distribution – An evaluation’. Paper presented at the CAUTHE Conference February 2005: Sharing tourism knowledge, Alice Springs, Australia

Gartner, W. C. and Bachri, T. (1994) ‘Tour operators’ role in the tourism distribution system: An Indonesian case study’. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 6(3/4), 161–79

King, B. and Choi, H. J. (1999) ‘Travel industry structure in fast growing but immature outbound markets: The case of Korea to Australia travel’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1(2), 111–22

Kotler, P., Bowen, J. and Makens, J. C. (1996) Marketingfor hospitality and tourism. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall

Middleton, V. T. C. and Clarke, J. (2001) Marketing in travel and tourism (3rd edn). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann

O’Connor, P. (1999) Electronic information distribution in tourism and hospitality. Wallingford: CABI Publishing

Pearce, D. G. (1993) ‘Comparative studies in tourism research’. In D. G. Pearce and R. W. Butler (eds), Tourism Research: Critiques and challenges. London: Routledge, pp. 20–35

Buhalis, D. (2002a) ‘New Zealand holiday travel to Samoa: A distribution channels approach’. Journal of Travel Research, 41(2), 197–205

Buhalis, D. (2002b) ‘Current and future directions in tourism research’. Japanese Journal of Tourism Research, 1(1), 9–20

Buhalis, D. (2003) ‘Tourism distribution channels: A systematic integrated approach’. In E. Ortega, L. González and E. Pérez del Campo (eds), Best paper proceedings of 6th International Forum on the Sciences, Techniques and Art Applied to Marketing. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid, pp. 345–63

Buhalis, D. (2004) ‘Advancing tourism research: Issues and responses’. In K. A. Smith and C. Schott (eds), Proceedings of the New Zealand Tourism and Hospitality Conference 2004. Wellington, NZ: Victoria University of Wellington, pp. 1–10

Buhalis, D. (2005) ‘Distribution channels for cultural tourism in Catalonia, Spain’. Current Issues in Tourism, 8(5), 424–45.

Pearce, D. G. and Schott, C. (2005) ‘Tourism distribution channels: The visitors’ perspective’. Journal of Travel Research, 44(1), 50–63

Pearce, D. G. and Tan, R. (2002) ‘Tourism distribution channels: A destination perspective’. In W. G. Croy (ed.), Proceedings of the 5th New Zealand Tourism and Hospitality Research Conference. Rotorua, New Zealand: Waiariki Institute of Technology, pp. 242–50

Pearce, D. G. and Tan, R. (2004) ‘Distribution channels for heritage and cultural tourism in New Zealand’. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 9(3), 225–37

Pearce, D. G. and Tan, R. (2006) ‘The distribution mix for tourism attractions in Rotorua, New Zealand’. Journal of Travel Research, 44(3), 250–58

Pearce, D. G., Tan, R. and Schott, C. (2004) ‘Tourism distribution channels in Wellington, New Zealand’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6(6), 397–410

Sharda, S. (2005) ‘The structure and behaviour of distribution channels linking destination New Zealand to an emerging market: A case of the Indian outbound travel industry’. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Sharda, S. and Pearce, D. G. (2005) ‘Distribution in emerging tourism markets: The case of Indian travel to New Zealand’. In S. J. Suh and Y. H. Hwang (eds), Asia Pacific Tourism Association 11th Conference Proceedings: New Tourism for Asia Pacific. Pusan, South Korea: Dong-A University, pp. 595–605

Smith, K. (2004) ‘“There is only one opportunity to get it right”: Challenges of surveying event visitors’. In K. A. Smith and C. Schott (eds), Proceedings of the New Zealand Tourism and Hospitality Conference 2004. Wellington, NZ: Victoria University of Wellington, pp. 386–97

Stuart, P., Pearce, D. G. and Weaver, A. (2005) ‘Tourism distribution channels in peripheral regions: The case of Southland, New Zealand’. Tourism Geographies, 7(3), 235–56

Tan, R. and Pearce, D. G. (2004) ‘Providers’ and intermediaries’ use of the Internet in tourism distribution’. In K. A. Smith and C. Schott (eds), New Zealand Tourism and Hospitality Research Conference 2004. Wellington, NZ: Victoria University of Wellington, pp. 424–32

Taniguchi, M. (2005) ‘The structure and function of the tourism distribution channels between Japan and New Zealand’. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Tourism Strategy Group (2001) New Zealand tourism strategy 2010. Wellington, NZ: Tourism Strategy Group

Wahab, S., Crampon, L. J. and Rothfield, L. M. (1976) Tourism marketing: A destination-oriented programme for the marketing of international tourism. London: Tourism International Press