Tourist arrivals have been a growing trended series over a long period of time with occasional shocks to arrivals first noticed with the Gulf Oil crisis of 1973. However, more recently these shocks have both widened in their variety of causes and increased in their frequency. This increasing diversity and frequency has drawn significant notice by several authors including Ennew (2003) and Wilks and Moore (2004) on tourism shocks and their impacts in general; Prideaux (1999), UNWTO (1998), Bromby (1999) and Roubini (1999) on the Asian financial crisis; Blake et al. (2001) and Scottish Government (2003) on the impact of foot and mouth disease on tourism in the UK; Blake and Sinclair (2002), ILO (2001) and Brewbaker (2002) on the impact of the 9/11 (11 September 2001) events; Aly and Strazicich (2000) and Pizam and Smith (2000) on terrorism impacts; Travel and Tourism in Hong Kong (Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2004), ATEC (2003) and Canada Tourism (2003) on SARS. Some of the literature tends to focus more upon the recovery process and whether there is a new trend to growth after the shock.

The degree of impact upon arrivals series has been significant enough to interfere with short-term forecasting and potentially medium-term arrival numbers depending upon recovery rates. Since most industry forecasting is short to medium term now, particularly as a result of the increasing uncertainty, but also because of shorter planning and investment cycles in western countries, there is an increasing need to have greater insight into the nature of shocks to tourist arrivals series. One starting point is to realise that the shocks can be generally categorised into types (see Table 7.1) and from this it is not difficult to hypothesise that different types of shock will have different strengths of impact on tourist arrivals. Wilks and Moore (2004) divide shocks into natural and manmade categories, but this simple dichotomy is not very detailed in regard to the wide range of manmade groupings. Another categorisation is to divide on the basis of impact in regard to direct or direct/indirect impact or duration. Indirect shocks are described to include the Asian financial crisis and the UK foot and mouth disease outbreak. However, the distinction is really quite unclear in that, seen from the point of view of tourist arrivals impact, neither of these shocks are indirect. Moreover, in regard to duration this is arguably less important than strength, and the two measures (strength and duration) are not the same.

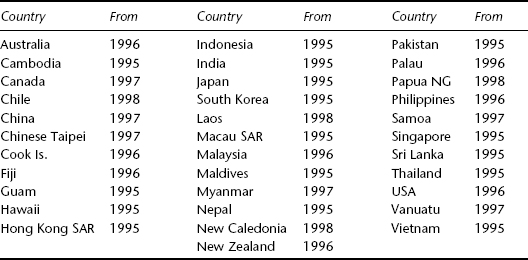

Table 7.1 Types of tourism shock

| Type of Shock | Public Start Month |

| Air Disasters | |

| Korean Air Guam | Aug-97 |

| * Singapore Airlines Chinese Taipei | Oct-00 |

Financial Crisis |

|

| * Asian Crisis | Jul-97 |

| Health Scare | |

| * SARS | Apr-03 |

| UK/Foot and Mouth Disease | Apr-01 |

Natural Disaster |

|

| * Guam Cyclone Paka | Dec-97 |

| * Guam Cyclone Pongsona | Dec-02 |

| Chinese Taipei earthquake | Sep-99 |

| Tsunami | Dec-04 |

| UK Heatwave | Jun-03 |

Political/War |

|

| Afghanistan | Oct-01 |

| China (Tiananmen Square) | Jun-89 |

| Fiji Coup 1 | Sep-87 |

| * Coup 2 | May-00 |

| Iraq Invasion | Mar-03 |

| Kosovo Conflict | Oct-98 |

| * Nepal Civil Conflict | Jun-01 |

| Persian Gulf War/Iraq | Jan-91 |

| Sri Lanka Civil War | 1983–2004 |

Terrorist Attack |

|

| * Bali | Oct-02 |

| Egypt/Luxor | Nov-97 |

| Japan Sarin Attack | Mar-95 |

| Kenya Bombing | Nov-02 |

| Philippines Hostage taking 1 | Apr-00 |

| Hostage taking 2 | May-01 |

| * World Trade Centre | Sep-01 |

| Yemen Attack on Cole | Sep-01 |

Note: * Shock selected for analysis. All start dates are not necessarily the first month the shock began but are the first month the shock became generally publicised.

Not all impacts will be negative and cause a reduction in arrivals in all destinations because tourists will substitute destinations on price and likely safety. Consequently, a shock in one destination may cause a decline in tourist arrivals that is then substituted to some degree by growth at another destination. It is not necessarily the case that substitution will be of like kind such as tropical island to alternative tropical island; the substitution could also take the form of a replacement holiday of a different type such as mountain trekking to sea diving/snorkelling. Consequently, unique destinations are also substitutable. There is also likely to be a geographic spread factor associated with shocks both in terms of the extent of destination market downturn, and also in regard to substitution. It is likely that the spread of substituted arrivals will be difficult to measure.

The objective of this research is to attempt to assess whether different shocks can be meaningfully categorised according to their impact, and, if so, whether this knowledge could be used to assess the impact of future shocks of particular types.

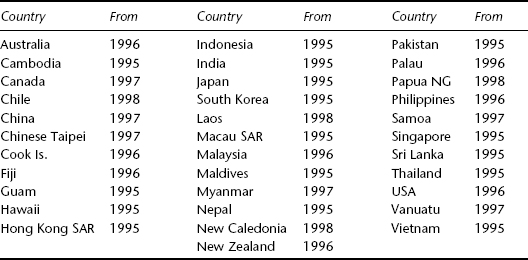

Data has been collected on a monthly arrivals basis for 34 countries and regional states over the period 1995–2003 (see Table 7.2). The Chinese Special Administrative Regions and the US regions of Hawaii and Guam have been treated as autonomous regions for the purpose of this study. Not all areas selected have series extending back to 1997, as there is variability between the countries on data availability. The countries/regions selected include all the destinations in Asia-Pacific and North America where data could be obtained. The choice of this world regional area is primarily because these are the regions where most shocks have occurred since 1997. The choice of shocks (see Table 7.1) also relates to the availability and extent of data and the intention to sample from each shock type. For example, the UK foot and mouth disease outbreak was not in the region selected. Data for China is unavailable prior to 1995. The Sri Lankan civil war was longitudinal and difficult to date for specific shock times. The data are supplied by the Pacific Asia Travel Association.

Monthly data has been used in order to be able to measure the depth and extent of shocks. Monthly arrivals are the lowest level of available tourist arrivals data. The data is measured as total arrivals. It would potentially be relevant to divide arrivals by the type of travel at least between holiday, business and VFR groups. It would be reasonable to hypothesise that the greater shock impact would fall on holiday travel in most cases and least on business travel with VFR falling somewhere between. However, data disaggregated by travel type and also monthly is not widely available, and the list of countries where this data can be obtained is relatively small in number.

Table 7.2 Time frame available monthly (from January of year shown) to December 2003

There would also be relevance in measuring flows by country of origin as opposed to total flows. However, again this becomes restrictively difficult. The number of destination flow changes becomes too large to adequately analyse. This is the reason that positive shocks also tend to be difficult to measure. Positive shocks are increasing tourist arrivals substituted away from destinations suffering negative shocks. These substitutions tend to be divided across numerous potential substitute destinations, so that individual positive shocks tend to be smaller than the larger, more geographically concentrated, negative shocks.

Not all the shocks are relevant to the 34 destinations under study, and some are beyond the time frame available for analysis. It is also difficult to distinguish some shocks occurring simultaneously such as the 2003 Iraq invasion and SARS.

The time-series for each destination has been examined for the period immediately following each of the relevant crises, with the objective of determining the greatest percentage decrease/ increase and the length in months of the decline/increase. This process involves calculating the percentage change in arrivals between each month and the average percentage change for each month. A decrease/increase is measured as the difference between the average change for the given month (measured over all years) and the percentage change at the time of the shock for the given month. This assumes that the change is a result of the shock, and, while this is to be expected close to the shock destination, it may become less certain further away, or in destinations where there is less relationship in the travel profile (source markets) between destinations.

The extent of the shock is measured by the time (in months) taken for the rate of growth to equal or exceed the average rate of growth for each month after the shock start, or in the case of an increase, the time in months taken for the rate of growth to drop back to the average rate of growth. These comparisons cannot be meaningfully translated into a total tourist arrival loss number, because the return to growth, while signalling the end of the shock, is a rate of growth from a lower/higher base number than would probably be the case if no shock had occurred; that is, the base number that would have been present without the shock remains unknown. Consequently, all that is determined is the percentage decrease/increase against the expected average and the duration in months of the shock.

These calculations most likely tend to underestimate the severity of the shock, because they measure against an expected average and that average evens out growth over several years including the shock year. Nevertheless, the expected average provides a stable benchmark for comparison that permits measurement of relative shock extent and duration well, and provides for a basis of comparison between shocks.

In most cases the change is a decrease but there are also some increases. Increases are not as well measured as decreases this way, because travel substitution mostly involves a spread across several destinations and is less universal across all markets, ideally requiring measurement at an individual origin/destination level, rather than total arrivals basis.

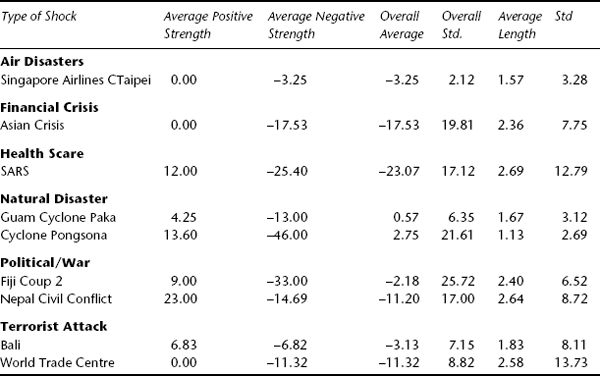

Table 7.3 displays the average and standard deviation results of the analysis for both maximum strength of impact and the duration in months of each shock. The statistics for average impact are divided between the positive and negative impacts. In some cases there were no beneficiary destinations from the shock, namely the airline crash, the Asian financial crisis and 9/11.

The political shock in Nepal yielded the highest average positive shock of 23 per cent, followed by cyclone Pongsona in Guam at 14 per cent. The negative results yielded higher averages, with the localised impact of cyclone Pongsona the highest average of −46 per cent. The average impact of the second political coup in Fiji and SARS were also high at −33 per cent and −25 per cent respectively. In terms of the overall averages, including both the positive and negative impacts, the cyclones in Guam yielded higher positive shocks than negative shocks. However, this was not the case for the other shocks which overall were negative, the highest being SARS at −23 per cent followed by the Asian financial crisis at −18 per cent, while perhaps surprisingly Nepal and 9/11 were roughly equal at −11 per cent.

Table 7.3 Summary statistics for the depth and length of shocks (per cent)

In terms of duration, SARS, Nepal and 9/11 were the longest at 3 months and cyclone Pongsona shortest at one month.

The highest variation in terms of strength across the study area was Fiji’s second coup, followed by Cyclone Pongsona. The highest variation in terms of duration was 9/11 and then SARS.

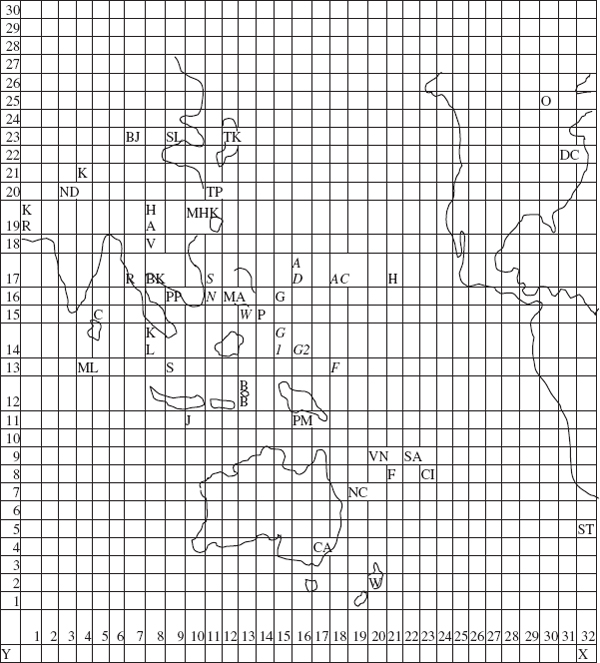

It is possible to look more closely at the geographic spread of the shocks. For this purpose the grid in Figure 7.1 has been created to show the relative locations of each of the capital cities for each of the sample countries.

The relative grid allows for the calculation of the mean centre for each shock and the standard distance deviation for the shocks calculated as weighted means of distance and co-ordinate standard deviations from the weighted means. Figure 7.1 displays these summary measures.

The average strength of the impact of all shocks clusters to the centre of the geographic region of study, as does the average duration of shock. That is, the impact of the shocks in terms of average strength and duration focus geographically to the centre, and tend to spread across the whole region. The degree of spread is better measured relatively by the standard distance deviation. In effect this is the radius of a circle based upon the mean centre. The larger the radius the greater the relative spread of the shock.

The Asian financial crisis and SARS demonstrate the largest geographic dispersion across the region of study in terms of strength of impact as shown by the standard distance deviations (5.01 and 5.13). SARS and 9/11 have the widest dispersion across the region in terms of duration of shock as shown in Figure 7.2 by the standard distance deviations (1.00 and 1.01). The lowest effect in terms of shock impact is the airline disaster (2.29) and the lowest impact in terms of duration are the Guam cyclones (0.80 and 0.79).

It is clear that SARS as a health scare had the greatest shock impact in terms of both strength and duration of the shock. Overall the Asian financial crisis was second, particularly in regard to severity of the shock. Furthermore, the political crisis in Nepal had a surprisingly strong impact although this was counterbalanced by strong positive substitution. In the case of natural disasters as represented by the Guam cyclones, the localised shock was very high, but strongly counter-balanced by strong substitution to alternative destinations; this was also true for the political impact of the coup in Fiji.

Note: WmeanCX – Weighted mean coordinate for x axis

WmeanCY – Weighted mean coordinate for y axis

Figure 7.1 Map grid of relative locations for the capital cities for each sample country strength

The 9/11 events were not as significant in this study region as SARS, the Asian financial crisis or Nepal, although the impact was virtually as strong as Nepal, and unlike Nepal not counterbalanced by any positive substitution.

Figure 7.2 Map grid of relative locations for the capital cities for each sample country duration

There is a significant difference between different political crises (Fiji and Nepal) and different terror attacks (Bali and 9/11). Although this may be expected (because the media focus on 9/11 and Nepal and the spectacular nature of the shocks far exceeded Bali and Fiji) the strength of the difference is large in the order of 8–9 per cent, and the lesser shocks (Fiji and Bali) are more in the order of the impact of the airline disaster overall.

Geographically, the shock strength and length tended to concentrate in the centre of the study region, indicating the overall impacts were not geographically different. However, the spread of the shocks geographically were different with SARS and the Asian financial crisis displaying the widest geographic impact in terms of strength, and SARS and 9/11 the widest impact in terms of length of shock. On the other hand the airline disaster had the least impact in strength across the region and the natural disasters the least impact in terms of duration across the region.

There are limitations in the data available for this analysis and consequently there must be some hesitation in deriving concrete conclusions from the results. Moreover the wide potential variety of shock types (as evidenced by the 2004 tsunami) must give cause for concern on basing forecasted impacts on such a limited sample. However, there are some inferences evident in this analysis. It appears that natural disasters have the strongest likelihood of generating positive travel substitution that may alleviate the overall tourist arrivals downturn; this also appears to be evident in localised political crises and terrorist attacks. On the other hand, it would seem that crises such as airline crashes and financial crises will be less likely to generate positive substitution, along with major geographically widespread shocks such as 9/11 and SARS.

SARS was the most significant shock studied in this data set and had the greatest strength of impact and duration. However, SARS also had a unique characteristic not evident with the other examples of shock. SARS had the month of maximum impact at different times in different countries, extending from March to June 2003. All the other shocks had the maximum impact in the month immediately after the date of occurrence. SARS rolled out across the study region over time as its media coverage extended to report on ever increasing incidents. In fact only a little over 8,000 cases were reported (far fewer than previous flu epidemics) and the death toll was relatively low. What set SARS apart as a high impact shock was the mass media interest and extended sensationalism over several months.

Although the assessment of the impact of the tsunami according to the above should be less because it is a natural disaster (being characterised by more substitution) a lesson was also learned from SARS: not to allow the media to expand the tourism downturn unnecessarily. Organisations such as PATA and the NTO in Thailand were very quick to argue that the best help people could offer was to return as soon as possible as tourists, to spend money in the local economies. Information on the exact extent of the disaster was made available quickly and accurately. Interviews and media stories were co-ordinated and released to counter each potentially sensational claim of travel downturns. This risk management approach may well be very effective with other shocks as they variously occur.

Consequently, while the evidence suggests that a health scare could be the most significant potential shock type, there may be ways by which industry can control unnecessary loss of business. However, if the health scare is genuinely significant then this type of shock has the greatest potential for high impact in terms of both strength and duration.

Localised shocks such as airline disasters, political turmoil and cyclones can be extremely severe in the local centres of shock, but are less likely to cause widespread travel downturns.

Different types of shock are evidenced to have different potential impacts. In the future the travel industry must be most concerned about a health scare, and if it is genuine prepare for a huge impact based on maximum downturns ranging close to 50 per cent and lasting several months. Financial crises and political turmoil are also highly dangerous to arrivals, and, although political crises can lead to positive substitution to some extent, they have the potential for high impact shocks of significant duration. Equally a 9/11-style attack would be severe and long in its impact if it is sensational in nature. Whereas more localised terror attacks may be severe for only the immediate destination. Natural disasters are characterised by high impact and high substitution, making their impact less overall.

Aly, H. Y. and Strazicich, M. C. (2000) Terrorism and tourism: Is the impact permanent or transitory? Time series evidence from some MENA countries. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University, Department of Economics

ATEC (2003) ‘SARS tourism downturn exceeds terrorism impacts’. Australian Tourism Export Council. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://www.atec.net.au/MediaReleaseSARS_Tourim_Downturn_Exceeds_TerrorismImpacts.htm

Blake, A. and Sinclair, M. T. (2002) ‘Tourism crisis management: Responding to September 11’. Discussion Paper No. 2002/7, DeHaan Institute, Nottingham University

Blake, A., Sinclair, M. T. and Sugiyarto, G. (2001) ‘The economy-wide effects of foot and mouth disease in the UK economy’. Cristel DeHaan Tourism and Travel Institute, Nottingham Business School. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://www.notingham.ac.uk/ttri

Brewbaker, P. H. (2002) ‘Hawaii economic trends’. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://www.hawaii.edu/hivandaids/Hawaii/Hawaii_Trends,_January_2003.pdf

Bromby, R. (1999) ‘South Korea leads race for recovery’. The Australian, 15 September

Canada Tourism (2003) ‘2003: A bad year for tourism’. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://www41.statcan.ca/2007/4007/ceb4007_002-eng.htm

Ennew, C. (2003) ‘Understanding the economic impact of tourism’. Som Nath Chib Memorial Lecture, 14 February 2003, DeHaan Institute, Nottingham University

Hong Kong Tourism (2004) ‘Hong Kong tourist arrivals down 6.2 percent in 2003, hit by SARS’. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://ehotelier.com/hospitality-news/item.php?id=A1110_0_11_0_M

ILO (2001) The social impact on the hotel and tourism sector of events subsequent to 11 September 2001. Geneva: International Labour Office

Pizam, A. and Smith, G. (2000) ‘Tourism and terrorism: A quantitative analysis of major terrorist acts and their impact on tourism destinations’. Tourism Economics, 6(2), 123–28

Prideaux, B. (1999) ‘Tourism perspectives of the Asian financial crisis: Lessons for the future’. Current Issues in Tourism, 2(4), 279–93

Roubini, N. (1999) ‘What caused Asia’s economic currency crisis and its global contagion?’. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://www.stern.nyu.edu/~nroubini/asia/AsiaHomepage.html

Scottish Government (2003) Economic impact of the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak in Scotland: Final report. Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://www.scotland.gov.uk/library5/agri/eifm-04.asp

UNWTO (1998) Asian financial crisis and its impact on tourism. Madrid: UN World Tourism Organization

Wilks, J. and Moore, S. (2004) Tourism risk management for the Asia-Pacific region: An authoritative guide for managing crises and disasters. Gold Coast MC, Queensland: Cooperative Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism