As the political climate changes and discussion of liberalisation intensifies, the involvement of the government in tourism policy – and especially in tourism marketing at the national level – has increasingly come to be called into question and challenged. As a political mega-trend of the twenty-first century, the pull-out of the government is seen in the context of the liberal economic doctrine as an all-purpose means of increasing economic performance, even when the government pulls out of its responsibilities in the production of public goods. In light of these tendencies, the effort will be made here to determine whether public involvement in tourism marketing – practically understood as the provision of financial support for activities related to tourism marketing – can be justified within the framework of liberal economic policy, and whether it is economically efficient. To compensate for the relative scarcity of literature on this topic, this paper relies primarily on the use of public economics tools. Organisational questions such as the legal form taken by national tourism organisations (NTOs) or the position occupied by public marketing departments in the relevant administrative hierarchies are not dealt with here.

General

Whether as company-oriented incentive systems or via involvement in tourism marketing, public support is an intervention in market mechanisms. For this reason, public involvement in market economies needs to be carefully justified. Economic theory offers several convincing approaches to such a justification for the public promotion of tourism. Some of the more important approaches are rooted in welfare economics.

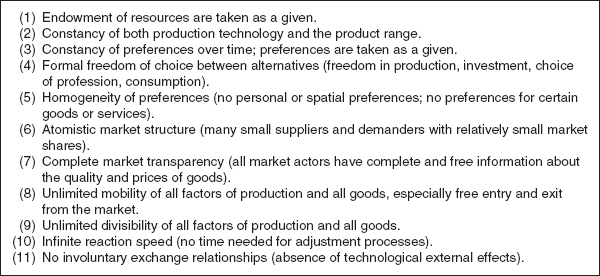

In welfare economics analysis begins with the premise that Pareto-optimal allocation of resources prevails, assuming there is perfect competition (see Figure 8.1). In other words, it is not possible to improve one person’s position by changing the allocation without making another person’s position worse. In a Pareto-optimal situation, public support makes no sense economically because it would reduce public welfare in general; that is, it is not possible to improve things for one person without making them worse for another. However, if a situation occurs where it is not possible to reach Pareto-efficient resource allocation, then there is a ‘market failure.’ The existence of market failures and also of market distortions justify public intervention in terms of improving market results (Bieger, 2000; Choy, 1993; Kerr et al., 2001; Pike, 2004; Smeral, 1998).

Figure 8.1 The assumptions made by the model of perfect competition

For economic theories characteristics, the perspective outlined here has an essential implication for economic and social policy which can be described as the liberal approach: as long as there are no well-founded counterarguments, individual, self-interested actions increase public welfare. This follows from the idea that self-interested actors will enter voluntarily into an exchange relationship only if it results in their benefit. Since it is generally assumed that individuals’ self-interested exchange relationships contribute to increases in overall economic welfare, the liberal doctrine points to the need for justifying any public interventions. This justification could lie in the market exchange relationship between two parties having a positive or negative effect on the welfare of a third party, or in that ‘market failure’ exists.

It must be said here that no criterion exists to precisely identify where market failure begins and ends. It will always be necessary to make a value judgment on the extent to which a market is working, or whether sufficient market failure exists to call for public intervention.

Economic thinking allows us to name four causes for market failure:

These four causes represent contradictions to the important suppositions made by the model of perfect competition. The theory of market failure is thus a systematic analysis of what happens when reality diverges from the assumptions of perfect competition.

In particular, external effects and information deficits play an important role in justifying public involvement in tourism marketing. Joseph Stiglitz recognised and discussed the importance of information asymmetries; in 2001 he received the Nobel Prize in Economics for his extraordinary work (Stiglitz, 2000).

In the context of liberal economic policy, what is also of decisive importance for the justification under discussion is the existence of relatively high transaction costs (e.g. due to a high fragmented supply) and companies often being too small (Müller and Scheurer, 2001). High transaction costs make cooperative efforts and destination development difficult; the reduction of these costs should be one of the main goals of modern tourism policy.

Considerations of transaction costs are not actually part of traditional approaches to the theory of market failure, yet just as external effects do, their existence justifies public intervention.

Where market failure exists, it is by no means automatically guaranteed that the state or any bureaucratic system commissioned by it will in fact be able to improve market results, as there is always the possibility of state and/or bureaucratic failures.

In the end, whether public intervention makes sense or not should be judged by considering whether the net welfare level is higher once the accompanying intervention costs have been taken into account, or whether it is higher when the imperfect market is left to itself.

External Effects

In tourism, it is especially the technological externalities which play a role. Such technological externalities exist when there is a physical connection between the production and utility functions of some actors that is not (or not fully) reflected in the relevant market relationships. The result is that the private costs and benefits (i.e. the payment flows experienced by the individual producers or consumers) diverge from the resulting overall social costs and benefits. The difference between these cost and benefit categories (e.g. social benefits minus private benefits, or social costs minus private costs) define the size of the technological external effects (benefits or costs). Where there are technological external effects, market prices are distorted reflections of the actual relations of scarcity because external benefits or costs are not considered.

For public tourism policy, technological externalities come into play because organisations without existing market relations engage in publicly funded marketing activities such as image building and brand management and in so doing generate benefits and income for a wide variety of businesses, for example hotels, restaurants, trading concerns, personal service providers, banks, insurance companies, legal and business service providers, agriculture and forestry, construction, and the food industry (Pearce, 1992). The overall economic benefit is thus significantly greater than individual benefits and income flows; for cost reasons – consider such examples as an image campaign in a foreign country – this overall benefit could not be realised by means of individual initiatives. This particular form of ‘market failure’, the existence of positive external effects, offers justification for public intervention (Nowotny, 1996). Publicly funded promotion measures are consistent with liberal economic policy only when they can be understood as ‘compensation’ for triggering positive external effects, or increases in overall economic welfare and/or improvements in market results. Based on individual interests, these positive external effects would not be possible or would be too small.

The scientific discussion takes it as a given that the market fails in allocating so-called ‘public goods’. Public goods must be produced by the government because the market fails to provide them. Accordingly, socially desirable goods that the market provides without any special intervention are called ‘private goods’.

In general, a good is called a ‘public good’ when it is not feasible to exclude anyone (at a justifiable cost) from its benefits. In the case of external benefits, non-excludability means that someone who does not pay for consuming the good is nevertheless not barred from consumption (this is the classic free-rider problem). Positive externalities thus come to the fore when no property rights exist – or when there is no way to enforce property rights without unjustifiable cost – so that a public producer cannot disallow actors such as certain hotels or linked industries from consuming the good in question for free. This may be the case with advertising effects, for example (Coase, 1960).

Three reasons can be suggested to explain why the exclusion principle cannot be applied:

The first two are relevant for tourism, since there are only a few exceptional (and often extreme) situations in which the technical conditions for excludability are not given, for example where the public good in question is police security or national defence.

‘Image’ is a good example of how difficult and costly it can be to enforce the exclusion principle in cases of external benefit. How would one even begin to go about explaining to a group of hotel guests which of their local hosts had contributed to what extent to their destination’s ‘image’? And what ostensible reason could a guest have to take advantage of only those local supplies whose sponsors had voluntarily contributed to building the destination’s image? Of course, it would be possible to offer premiums to guests who frequent only the businesses of the contributors, but administration costs coupled with the cost of compensating for quality and preference differences would make a loss of any such venture. A further difficulty would be presented by a whole row of businesses such as restaurants, trading concerns, banks, insurance companies, tax advisers and construction firms that benefit only partially from image campaigns.

Because tourism providers who contribute nothing to image building are free-riders who enjoy the benefits of this public good, a situation which results in positive externalities, attempts to finance image building via voluntary contributions would most likely lead to overall under-financing of the undertaking.

If excludability cannot be enforced because of technological externalities (whether for economic or political reasons), it stands to reason that government corrects the market failure and takes steps to provide the good in question, covering the associated costs with public funds. In this context, one speaks of the provision of public goods. The provider can be the government itself or a public service provider (here, an NTO) commissioned by the government. Determining the extent of the public good to be provided and ensuring that it reaches its intended target group can present problems. Theoretically, the optimal amount of a (public) good with externalities is given when the totals of the marginal individual willingness to pay and the marginal costs of providing the public good are equal to one another. Conceivably, a survey or a poll might be taken among the relevant actors in order to determine their willingness to pay, so that the public good could be publicly funded in that amount. However, it must be expected that the relevant actors will act strategically, so that attempts to acquire undistorted information must be made in a very careful manner. Potential free-riders will tend to disguise their true willingness to pay by naming a low value or even total disinterest; the lower the collective willingness to pay is calculated to be, the lower each individual’s contribution to public funding via taxes would be. On the other hand, if such a survey or poll is taken among actors who feel certain that their preference for the public good will have no effect on their personal tax burden, they will tend to exaggerate their willingness to pay; by naming disproportionately high amounts, potential free-riders would be able to increase their benefit levels.

Further, public goods have the property of non-rival consumption. This means that the consumption of a public good by an additional consumer leads to no or only negligible marginal cost. One example of this is the benefit accruing to each additional tourism provider as a result of image campaigns and brand management measures.

Public goods characteristically also cannot be rejected. For example, hotel owners who attempted to do this would have to ask each of their guests whether it was publicly funded advertising which had led to their choice of destination; if the answer were yes and the hotel owner had not paid the financial contribution, then the guest would have to be turned away.

Information Deficits

Information deficits on the part of market actors can impair a market’s functioning so that market failure occurs. It is important to differentiate here between lack of knowledge and uncertainty.

Lack of knowledge occurs when market actors simply possess insufficient information, whereby it is possible in principle to close such a knowledge gap. Uncertainty, on the other hand, has to do with future developments, thus representing an information deficit which cannot be remedied, because not even the best forecast made with maximum effort can provide absolute certainty.

Lack of information plays a role in market relationships where market actors on one side are better informed than market actors on the other side. This is described as an asymmetrical distribution of information. In tourism, it is above all the lack of knowledge about the quality of the goods and services being offered that plays a role. Lack of knowledge about benefits is another form of information deficit.

The consequences of information asymmetries that exist at the buyer’s expense can be described as in the following.

One can safely assume that there exist differing quality levels among tourist products. If tourists are able to gain exact knowledge of the quality being offered to them, they can adjust their willingness to pay. In other words, a tourist would be willing to pay a higher price for higher quality and a lower price for relatively low quality. Typically, however, a tourist can assess the true and final quality only after conclusion of the contract because there is an information gap between the contractual agreement and the actual quality of a tourism product. In order to minimise risk, tourists would adjust their willingness to pay to their expectation of what the average quality will be. However, which level of quality an individual tourist will actually encounter is a matter of fortune, be it good or ill.

If tourists adjust their willingness to pay to average quality expectations, then suppliers who offer above-average quality and thus have above-average costs will have relatively low profits or even losses. Even where providers are interested in selling high quality, tourists’ information-deficit-induced behaviour forces providers to offer lower-quality goods. If tourists then realise that the average quality is falling, the prices they are prepared to pay will also fall. This leads to reductions in high-quality tourist offerings, so that prices continue to fall, a process which in the worst case continues until only the lowest possible quality is offered and the tourism markets for high quality collapse completely. Low quality pushes high quality out of the market and the resulting prices are accordingly low. This process can be described as ‘adverse selection’ and leads to tourism market failures. Consequently, government intervention aimed at eliminating information deficits is justified.

Adverse selection at the expense of the buyer is often to be encountered in the case of goods with experience quality as well as in the case of confidence goods.

The quality of experience goods can be judged only after they have been purchased and consumed. Examples include the quality of the meals and other services in a vacation hotel. Confidence goods’ lack of quality can be judged only after one has consumed a certain amount of them. In many cases, tourists can never judge the quality of goods consumed (e.g. water quality or food quality).

It is evident that by fulfilling the mandate to disseminate information, public tourism policy can make a significant contribution to bridging the information gap; whether it is by means of media campaigns, events, the electronic presentation of the different tourism products or other activities, public tourism policy can improve market results.

Adverse selection can also present itself as a problem for tourism providers when they cannot estimate the demand for their services exactly enough. For example, tourists cause considerable costs if they have especially high expectations and/or many special wishes. If providers do not have the market knowledge necessary to assess tourists’ expectations ex ante, they will calculate their prices so that they will not take a loss on average. However, since this price will be relatively high for more unassuming guests, these guests will forgo the offer. At the same time, there will be more guests with higher expectations who find the offer to be relatively cheap. The result is that prices rise, discouraging even more of the guests who expect less. Tourists with more modest expectations would indeed book vacations but the prices are too high because the providers are not able to accurately assess ex ante the cost risks posed by different customer groups. In other words, market results suffer from an information gap between supply and demand and market failure occurs. In offering market-specific knowledge, in making recommendations for services to be provided and in making the results of market research available, public tourism policy can contribute to bridging or even closing the information gap and thus improving market results.

Where information is lacking, the benefits of certain goods may be systematically falsely appraised so that there comes to be too much or too little demand for them. This is an example of lack of knowledge about benefits.

Lack of knowledge about benefits differs from lack of knowledge about quality in that benefit estimates are wrong even when there is complete certainty about the offer’s quality. The further the benefit of a good lies in the future, the more difficult it generally is to assess it. A typical tourism example is a vacation taken as a health care measure (preventive wellness vacation). The prevailing assumption is that potential health vacationers underestimate the benefits of preventive wellness vacations and – at least in their younger years – consume too few of them. Further examples are vacations and journeys made for educational purposes. In all these cases, organisations that implement national tourism policies raise the informational level and improve overall market results.

Market failure also occurs where businesses experience entrepreneurial insecurity. This is assumed to be the case especially because – in the overall economic context – businesses are too risk-averse and thus invest too little in research. Overly careful practices can diminish market results and exaggerated caution can lead to market failure. In that it offers research results, forecasts and future scenarios, public tourism policy can help to reduce entrepreneurial insecurity and thus to improve market results.

Transaction Costs

Transactions costs that arise from initiating, negotiating, handling, controlling and adjusting contracts can negatively influence market results. Where the government does not take action to correct the situation, transaction costs – for example from asserting property rights, from transferring services between businesses, from identifying appropriate transaction partners or from internalising external effects – act as a transaction barrier and prevent the achievement of a Pareto-efficient market situation (Keller, 1999; Williamson, 1975). In other words, transaction costs that are too high lead to supply shortfalls, a situation which should be remedied by government action in the interest of general welfare (Palmer and Bejou, 1995; Pechlaner and Weiermair, 1999). Public tourism policy seeks to reduce transaction costs by assisting in and promoting the development of cooperative efforts and destinations, in order to make tourism supplies possible where high transaction costs would otherwise preclude it. In the context of liberal economic policy, public tourism policy is justified because it is a case of government’s exercising influence to reduce businesses’ external costs and thus positively influence market results.

General

On the basis of the theory of market failure and the existence of cost-related transaction barriers, only the necessary reasons for government involvement can be described. In order for economic policy to lead to increased overall economic welfare, additional cost–benefit analyses must be made to ensure that the sufficient conditions for government involvement exist. Public measures are advantageous where the expected benefit (i.e. the positive effect for overall welfare) is greater than the cost involved; ideally, and in the event that they are known, the benefits resulting from the best possible alternative should be taken as the measure of this cost.

Since there is a lack of comprehensive quantitative information on the economic consequences of public measures, these theoretical efforts come to grief in terms of their practical application, as is commonly the case. Recognising these deficits, we must rely on indicators, suppositions, secondary material and estimates.

Effects of Tourism Marketing

Firstly, the impact of tourism marketing must be assessed, to which end relevant research results can be referenced.

Crouch presents a meta-analysis of some 80 studies that focused primarily on tourism demand (Crouch, 1995). Among other factors, the effects of NTO marketing budgets on the development of tourism demand were discussed by these studies. A central result of Crouch’s international study was that tourism demand from abroad shows an average elasticity somewhere between 0.2 and 0.3 in relation to NTO marketing budgets. Although these figures seem to be inflated, obviously because of the difficulties inherent in properly isolating all the effects that impact on tourism demand, they do clearly demonstrate that tourism marketing has a considerable and measurable impact.

Tourism’s Effects on Value Added, Employment and Growth

Tourism marketing is overall economic efficient because of its large value added and employment effects. It is safe to assume that if promotional measures are taken which have similar impacts on the various components of the final demand such as private consumption, investments and visible exports, then tourism as another component of the final demand will trigger conspicuously above-average value added effects. Here, input–output analysis presents unambiguous results.

The results shown to us by input–output analysis are those of the cumulative processes set into motion by tourism demand.

In 2000 in Austria, every €1,000 of tourism demand from abroad led to €820 in value added (see Table 8.1). The hotel and restaurant sector profited most, followed by retail trade, the food processing industries, and the transportation sector.

The input–output table for 2000 represents no special information on tourism demand from Austrian residents, but experience with previous analyses and other studies allow us to assume that there are no significant differences between the consumption structures of residents and foreign visitors or between the relevant value added multipliers.

Along with public consumption, tourism has the highest value-added effect in relation to demand increases resulting from measures of economic policy (see Table 8.1, ‘foreign visitors’ consumption’, ‘government’) (Smeral, 1995). All other value-added effects in the areas of investment or export are significantly lower.

International comparison of tourism’s value-added effects are quite difficult because of varying concepts; nevertheless it is safe to say that due to developed nations’ generally low import quotas of tourism demand, as a matter of principle the value-added effects in most of these countries will also be above average.

Tourism results not only in high value-added effects; in the Austrian national economy – as in many other national economies – it has also become a highly significant economic factor. Tourism-related production provides the sole livelihood and means of subsistence for entire population segments. In other words, public involvement in tourism marketing contributes to ensuring these people’s livelihoods, especially those in SMEs in rural areas. It should be mentioned here that promotion and strengthening of structures with a location-based, quasi-monopolistic position (e.g. winter sport, or cultural assets such as music or city ambience) should be preferred to measures concentrating on sectors that are not differentiated enough and have to move to countries with, for example, lower costs, taxes.

Table 8.1 Value added multipliers per unit of overall demand: input–output table for the year 2000

| Sector | Value added multiplier |

| Residents’ Consumption | 0.73 |

| Foreign Visitors’ Consumption | 0.82 |

| Government | 0.89 |

| Building Investments | 0.79 |

| Equipment Investments | 0.35 |

| Exports | 0.67 |

Tourism’s significance for the national economy and its overall economic contribution to value added is an important indicator for economic policy (OECD, 2000; UNWTO, 2001). The results of the Tourism Satellite Accounts (TSA) can be used to determine this crucial indicator (Laimer and Smeral, 2004; Smeral, 2005): using the TSA concept it was calculated for Austria that direct tourism-related value-added effects accounted for 6.6 per cent of GDP in 2004. A proper overall comparison should, however, also consider the indirect effects exclusive of the business trips of residents. After correcting the TSA results accordingly, it was calculated for Austria that direct and indirect value-added effects accounted for some 9 per cent of GDP in 2004; tourism generated a sales volume of €28.24 billion.

Because of data inavailabilities and the limited implementation of TSA concepts, it is difficult to carry out theoretically correct comparisons of economic significance, so that we must rely on the use of indicators. A relatively strong indicator is the share of tourism exports in GDP. Table 8.2 shows that, while the EU-25 average is approximately 2 per cent, countries such as Austria, Italy, Spain and the 10 new EU countries, as well as non-EU member Switzerland, all show above-average shares in GDP.

Even though the Table 8.2 shows the overall economic importance of tourism only on the basis of the direct effects of tourism exports and thus greatly underestimates it (in general by some 100–150 per cent),1 the important place that tourism has in the economy is nevertheless very clear. Correct consideration of business trips remains a conceptual problem but influences the overall results only minimally.

Table 8.2 Share of tourism exports in GDP

| Country | % |

| EU-15 | 2.07 |

| Austria | 5.50 |

| Germany | 0.96 |

| France | 2.11 |

| Italy | 2.13 |

| Spain | 4.97 |

| Great Britain | 1.27 |

| 10 new EU-members | 3.51 |

| EU-25 | 2.14 |

| Switzerland | 2.90 |

| USA | 0.76 |

| Japan | 0.09 |

| Russia | 1.04 |

| Brasil | 0.50 |

| India | 0.59 |

| China | 1.23 |

| Total | 1.22 |

Source: UNWTO, 2001

Table 8.3 Employment multipliers per €100,000 of overall demand, input-output table for the year 2000

| Sector | Employment multipliers |

| Residents’ consumption | 1.3 |

| Foreign visitors consumption | 1.9 |

| Government | 1.8 |

| Building investments | 1.4 |

| Equipment investments | 0.6 |

| Exports | 1.0 |

It should also be considered that tourism is one of the fastest growing areas of demand around the world, so that marketing measures will tend to have greater impact here than in other areas (Costa, 1997; Pike, 2004; Smeral, 2003a, 2003b). Since 1980 the industrialised2 countries’ income from international tourism (real tourism exports) have grown by 4 per cent per year. Compared to the overall economic expansion rate in industrialised nations of some 2½ per cent per year (1980–2004), the above-average growth of tourism becomes quite apparent.

The employment multipliers resulting from tourism demand are the highest in the entire economy (Pike, 2004; Smeral, 1995), due in part to tourism’s relatively low import quota (see Table 8.3). It is also due to relatively low labour productivity/relatively high labour intensity in hotels and restaurants, which is in turn mostly due to the specific production conditions, the scarcity of opportunities for technical rationalisation and the structural under-utilisation resulting from seasonal fluctuations in demand.

In Austria, the employment multiplier of foreign tourism demand was 1.9 per €100,000; calculating in the price and productivity increases that took place between 2000 and 2004, the employment multiplier is estimated to decrease by around 10–15 per cent.

In fact, tourism’s employment effect presents the strongest argument for promoting tourism. Tourism is a driving force in the creation of jobs, especially for young people, and a significant source of employment in most industrialised and developing countries.

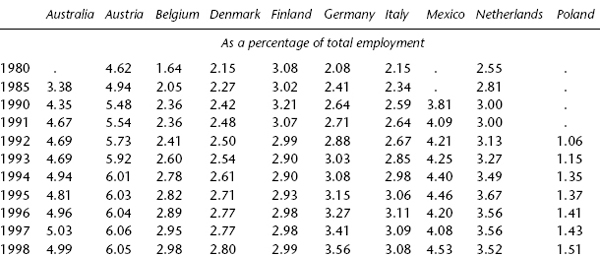

It should also be emphasised that in most industrialised nations the number of employees in hotels and restaurants relative to total employment numbers grew on average in the 1990s – in contrast to overall trends in industrial employment (see Table 8.4).

Table 8.4 Development of employees in the hotel and restaurant industry in selected countries

Source: OECD, 2000

The analysis has shown that the conditions calling for both necessary and sufficient conditions are fulfilled, thus in the context of liberal economic policy, public funding of tourism marketing is justified, provided that government and bureaucracy failures can be precluded.

In formulating this justification, the occurrence of market failures – in particular, external effects and information asymmetries – and the existence of relatively high transaction costs play an important role.

NTOs’ marketing activities such as image building and brand management generate positive external effects (i.e. benefits and income) for numerous businesses (hotels, restaurants, retail trade, personal service providers, banks, insurance companies, legal and business service providers, agriculture and forestry, construction, the food industry, etc.). This justifies public funding of such marketing activities, because it can be understood as a payment for generating external effects.

Information deficits describe situations in which one market participant is better informed than the other side (e.g. customer – supplier). In tourism, it is mostly the lack of information about quality that plays a role.

Lack of information about quality exists when tourists demanding a good such as the activities offered at a destination cannot adequately assess that good’s quality. Here, the seller is better informed than the buyer and the information is distributed asymmetrically. Lack of information about quality can also come into play where tourists are (naturally) better informed about their quality expectations than their potential hosts are. Regardless of who is affected by a lack of information, competition could lead to situations in which the market for good quality will break down. Closing the information gap is therefore an important goal of public tourism policy, particularly because public intervention would improve market results.

Transaction costs might be a serious obstacle for the achievement of a Pareto-efficient market situation. Too high transaction costs could lead to supply shortfalls. Public tourism policy should focus reducing transaction costs by promoting the development of integrated destinations, in order to increase and/or improve tourism supplies.

Market failures and the existence of transaction costs describe only the necessary conditions for government involvement. For increasing the overall economic welfare, additional cost–benefit analyses must be made. In this context, the facts can be presented:

1 Domestic tourism as well as the indirect effects are not considered.

2 Here the following definition is used: EU-15, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, Canada, USA, Mexico, Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

Bieger, T. (2000) ‘Perspektiven der Tourismuspolitik in traditionellen alpinen Tourismusländern: Welche Aufgaben hat der Staat noch?’. Tourismus Jahrbuch, 4(1), 113–36

Choy, D. J. L. (1993) ‘Alternative roles of national tourism organizations’. Tourism Management, 14(5), 357–65

Coase, R. H. (1960) ‘The problem of social costs’. Journal of Law and Economics, 3(2), 1–44

Costa, D. L. (1997, June) Less of a luxury: The rise of recreation since 1888 (Working Paper 6054). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research

Crouch, G. I. (1995) ‘A meta-analysis of tourism demand’. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 103–18

Keller, P. (1999) ‘Zukunftsorientierte Tourismuspolitik – Synthese des 49: AIEST-Kongresses’. Tourist Review, 54(3), 13–17

Kerr, B., Barron, G. and Wood, R. C. (2001) ‘Politics, policy and regional tourism administration: A case examination of Scottish area tourist board funding’. Tourism Management, 22(6), 649–57

Laimer, P. and Smeral, E. (2004) Ein Tourismus-Satellitenkonto für Österreich: Methodik, Ergebnisse und Prognosen für die Jahre 2000–2005. Vienna: WIFO

Müller, H. and Scheurer, R. (2001) Tourismuspolitisches Leitbild des Kantons Bern. Bern: Amt für wirtschaftliche Entwicklung (KAWE)

Nowotny, E. (1996) Der öffentliche Sektor (3rd edn). Berlin: Springer

OECD (2000) ‘Measuring the role of tourism in OECD economies: The OECD manual on Tourism Satellite Accounts and Employment’. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Palmer, A. and Bejou, D. (1995) ‘Tourism destination marketing alliances’. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(3), 616–29

Pearce, D. G. (1992) Tourist organizations. New York: Wiley

Pechlaner, H. and Weiermair, K. (eds) (1999) Destinations-management: Führung und Vermarktung von touristischen Zielgebieten. Vienna: Linde-Verlag

Pike, S. (2004) Destination marketing organisations. Amsterdam: Elsevier

Smeral, E. (1995) ‘The economic impact of tourism in Austria’. The Tourist Review, 51(3), 18–22

Smeral, E. (1998) ‘The impact of globalization on small and medium enterprises: New challenges for tourism policies in European countries’. Tourism Management, 19(4), 371–80

Smeral, E. (2003a) ‘A structural view of tourism growth’. Tourism Economics, 9(1), 77–93

Smeral, E. (2003b) Die Zukunft des internationalen Tourismus: Visionen für das 21. Jahrhundert. Vienna: Linde-Verlag

Smeral, E. (2005) ‘The economic impact of tourism: Beyond satellite accounts’. Tourism Analysis, 10(1), 55–64

Stiglitz, J. E. (2000) Economics of the public sector (3rd edn). New York: W. W. Norton

Williamson, O. E. (1975) Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications: A study in the economics of internal organization. New York: Free Press

UNWTO (2001) Tourism Satellite Account: Recommended methodological framework. Madrid: UN World Tourism Organization