Over the past two decades, sustainable development has become a core concept of tourism planning (Weaver, 2008; Smith, 2001). Stakeholder analysis, particularly of host community residents, has become an integral element of resort planning (Perdue, 2003), with the goal of improving local quality of life and economic opportunity. Numerous studies of host community residents have been conducted, focusing on perceptions of tourism’s impacts, support for tourism development, and attitudes toward tourism growth management (i.e. Andereck and Vogt, 2000; Korça, 1998; McGehee and Andereck, 2004; Perdue et al., 1990). These studies have consistently identified the effects of tourism development on the cost and availability of real estate as one of the primary impacts of tourism in resort communities (Perdue et al., 1999).

In many resort communities, much of the housing stock is purchased by tourists as second homes both for use during vacations and as an investment. This demand for second homes affects both the character and price of the housing stock. First, particularly in major resort destinations, second homes tend to be large, amenity-rich developments that are naturally much more expensive than the traditional local housing stock (Hall and Müller, 2004a, 2004b). Second, due to the common scarcity of developable land in resort communities, the available housing stock is limited. Second home demand adds to that scarcity, thereby further increasing prices (Cho et al., 2003). Because of these prices, second home demand can lead to a process of gentrification, wherein lower-income full-time residents are unable to purchase homes in the resort community leading to a process of “class colonization” (Phillips, 1993).

A substantial body of research exists examining the distribution of second homes, ownership trends, and impacts of second home development (most notably, Coppock, 1977a; Hall and Müller, 2004b). While this existing research provides an excellent general description of the second home phenomena and its impacts, much of it is not directly applicable to the high-end, luxury second home industry that characterizes most Colorado ski resort communities (Perdue, 2004). Three primary limitations exist in applying the existing second home research to Colorado ski resort communities. First, as with most products, great variance exists within the concept of second homes, ranging from small cabins in remote settings to elaborate trophy homes in gated resort communities (Curry, 2003; Egan, 2000). The existing research has not segmented the second home market and examined differences by product type. Rather, the predominant focus is on describing the “average” second home, the “average” second home owner and overall trends in the marketplace (e.g. Timothy, 2004).

Second, due to the availability of data, much of the second home research has been conducted in Canada and Europe, particularly Great Britain and the Scandinavian countries (e.g. Coppock, 1977a, or Hall and Müller, 2004a). While this research is clearly important and insightful, differences in land ownership and real property tax laws limit its applicability to Colorado resort communities.

Third, as with much of the existing second home research, this research program is motivated by the need for information to guide government policy concerning second home development (Gill, 2000; Gill and Williams, 1994). The existing research clearly indicates that second home development potentially has substantial economic and social impacts on local communities (Müller et al., 2004) and that those impacts vary by community (Coppock, 1977b). It is essential to examine the unique characteristics of Colorado ski resort communities and to understand the implications of those unique characteristics to both second home development and the associated policies.

Thus, the goals of this research program are to develop an inventory of second homes in selected Colorado counties, to examine the economic and social impacts of second home development, and to forecast future development patterns. The purposes of this paper are:

The following sections will provide further background into some unique characteristics of the selected Colorado ski resort communities, describe the preliminary research methodology, and present and discuss the resulting data within the context of the existing research. The paper concludes with our proposed research agenda.

This research was conducted within four counties of the Northwest Council of Governments Region of Colorado. These four counties include a number of the world’s premier ski resorts. Specifically, the study region included Summit County (Keystone, Breckenridge, and Copper Mountain ski resorts), Eagle County (Vail and Beaver Creek), Grand County (Winter Park), and Pitkin County (Aspen and Snowmass). Collectively, these areas hosted approximately 8 million skier days during the 2003/4 season (Colorado Ski Country USA, 2004). With a combined population of less than 100,000 people, this region experienced over 7,000 property transactions in 2003 alone with an aggregate value exceeding $3.8 billion (Blevins, 2004; US Census Bureau, 2005). Jackson County was not included in the study as it is primarily a rural, agricultural county and has little second home development.

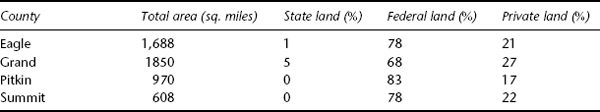

Between 1990 and 2000, the study region was the fastest growing region within Colorado with an overall 73 percent population growth. The region’s Hispanic population during the same time period experienced 268 percent growth. Regarding the available labor force and projected job growth, although annual skier visits have remained somewhat constant at about 8 million, job growth has outpaced available workers (CSDO, 2003). In 1999 in Summit County, with annual skier days averaging about 3.5 million over the past few years, there was a shortage of over 4,000 workers. In Eagle County, there was a labor force shortage of 9,797 workers in 1997, a shortage that is expected to grow substantially (estimated to be 20,000 or more) by 2020 potentially increasing the number of workers either needing affordable local housing or being required to commute to their place of employment.

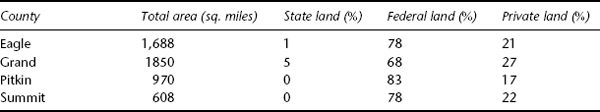

Table 10.1 Study region land ownership

Three unique characteristics of this region and the associated ski resorts have dramatically influenced second home development. First, in most Colorado ski resort communities, the developable land is extremely limited. Much of the land (up to 80 percent in some counties) is owned by federal, state, or local governments and, consequently, unavailable for development (Table 10.1). Further, of the developable land, much cannot be developed due to steepness of slopes, classification as wetlands, and lack of access. If fact, a critical environmental impact issue is the growing tendency to develop these marginal lands, due to scarcity of better, more developable land.

Second, the ownership of Colorado ski resorts has fundamentally changed over the past few decades. An industry historically characterized by independent, privately owned, entrepreneurial companies has transformed into a consolidated, publicly owned, corporate industry. The emergence of Vail Resorts, Inc. (NYSE: MTN) and Intrawest, Inc (NYSE: IDR) has dramatically altered business practices in many Colorado ski resort communities. Vail Resorts, Inc. owns and manages Vail, Beaver Creek, Keystone, and Breckenridge ski resorts in the study region. Intrawest, Inc. owns Copper Mountain Resort, is a development partner in Keystone Resort, and has recently entered into management agreements to redevelop the Winter Park and Snowmass Resorts, all within the study region. The transition to public ownership, with its focus on shareholder value and quarterly profits, has greatly accelerated real estate development at these resorts (Clifford, 2002). As the speed of development increases, the associated impacts are magnified (Perdue et al., 1999).

Figure 10.1 Population, jobs and skier visits: Summit County Colorado

Third, Colorado ski resorts are increasingly competing for share in a stagnant market. A primary tactic in this competition has been product improvements in the form of terrain expansions and lift capacity improvements, both of which are very expensive. Replacing a standard double chairlift with a high speed detachable quad lift is at least $6–8 million dollars per mile. A gondola lift costs in the range of $10–12 million. Even when excluding the highly variable litigation costs of gaining the development permits, the costs of terrain expansion are equally impressive; the Blue Sky Basin expansion at Vail Resorts is estimated to have cost $18 million. Further, today’s destination skier also expects a complete range of restaurant facilities on the mountains, other winter recreation facilities such as sledding and ice skating, and other amenities, such as warming huts and business centers. The Two Elk Restaurant complex on Vail Mountain is a $12 million facility. Over the last decade, more than $1 billion has been invested in mountain expansions and improvements at existing Colorado ski resorts (Lipsher, 2002). As part of its agreement to manage Winter Park Resort for the City of Denver, Intrawest has agreed to invest $50 million in mountain improvements over the next decade. Much of this expansion is being financed by real estate development and management, further accelerating the level of second home development. In exchange for its Winter Park mountain investments, Intrawest was given development rights to 140 acres at the base of the mountain and is planning between 1,000 and 1,500 new condominiums along with approximately 50,000 sq ft of commercial space.

Typology of second homes

The first, and not insignificant, challenge of examining second homes in resort regions is developing a viable database that identifies second homes. This is traditionally done on the basis of the owner’s primary place of residence. To determine the profile of second homes for the study region, county assessor databases from the four counties were collected and assembled into a GIS database of over 64,000 property records. The database reflected 2000–2001 housing ownership information. These records were recoded to reflect common fields including type of unit (e.g. single family home, condominium), value of unit, square footage and year built. Because there is no indicator within County Assessor records for whether a home is being used as a second home or local residence, a code was added to indicate the current usage of the housing unit based on where the property tax assessment notice was being sent. Out-of-county addresses were marked as “second home.” Using this method it was determined that 60 percent of the homes in the four-county study area are second homes. This ranged from a low of 49 percent in Eagle County to a high of 67 percent in Summit County.

Analysis of property values in the study area showed the average price of a single family house in June 2003 in Eagle County to be $785,000 whereas for a multifamily unit (duplex, triplex) the average was $443,000. In Summit County the average for single family housing was $486,000, for multifamily, $255,000. These high-end housing costs and related issues were prominently noted in a July 2004, Denver Post newspaper article entitled “Resort sales on a record pace” (Blevins, 2004). The writer indicated that the second home real estate market was being bolstered by “strengthening stock market, baby boomers boasting more discretionary income, lower interest rates luring locals out of the rental pool and climbing prices” and noted that “High-end buyers are driving the surge, especially in Aspen and Pitkin County.” He also noted that “New homes are becoming more rare. New land becomes unavailable. Space gets tighter and values soar.”

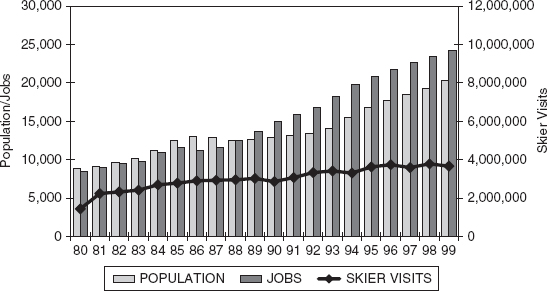

The standard US home market value in 2004 was roughly $100,000; in Pitkin County it was in excess of $1 million; in Eagle County the average exceeded $550,000. The percentage increase in home market values in 1998–2004 for the standard US city was about 18 percent; for Grand County it was over 60 percent and for Eagle County it was in excess of 75 percent.

Further analysis of housing cost data showed that as the value of second home property increased, so did the percentage of second home ownership. For example, 74 percent of those properties valued in excess of $5 million were owned by second home owners whereas only 57 percent of those properties valued in the $100,000 to $200,000 price range were determined to be second homes. Additionally, a large percentage of the study area’s housing stock with the highest square footage was owned by second home owners: 67 percent of the homes of 7,000 sq. ft. or more were identified as second homes as were 59 percent of those with 4,000–4,999 sq. ft., 64 percent of those with 5–5,999 sq. ft. and 64 percent of those with 6–6,999 sq. ft. The most common types of second home were condominiums (72 percent) and single family homes (48 percent).

These findings illustrate a number of critical questions for future research. First and foremost, it is important to establish the trend lines in these data. Presuming the levels of growth observed by the popular media and through casual observation, the implications for ownership, size, and amenity characteristics of resort real estate are important both for resort developers and public policy organizations. Second, what are the policy implications of this gentrification process? Third, where will the resort employees live and how will they commute to and from the resort workplace? Colorado Highway 82 between Glenwood Springs and Aspen is rapidly becoming an urban highway with daily commuter traffic issues.

Figure 10.2 Percentage increase in home market values: 1998–2004

Survey of Second Homeowners and Residents

In order to learn about utilization, shopping patterns and behaviors of second homeowners it was necessary to seek information directly from the homeowners. It was also important to determine the similarities and differences of attitudes and opinions of both permanent residents and second home owners for future planning. A questionnaire was sent to a stratified random sample of all homeowners (n = number of homeowners = 64,000, 60 percent of which had been determined to be second homes) in the four-county study area in April 2003; of the 4,300 questionnaires mailed, 1,346 were returned for an overall useable response rate of 32 percent. Some 41 percent of the respondents indicated this was their permanent residence while 56 percent indicated it was their second home used for personal or rental use.

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic questions asked in the questionnaire provided for a comparison of second home owners in the region with those described in the National Study of Second Homeowners published in American Demographics (Francese, 2003). This national study identified 55–64 as the age cohort most likely to purchase second homes and forecasted great growth in the second home industry nationally as baby boomers (1946–64) are just beginning to enter this age cohort. It was reported that second home owners nationally tend to be high-income, high-asset, highly educated, middle age or older couples, with children nearing adulthood or children no longer living at home. This study confirmed all of these characteristics but showed much higher income levels and even a greater likelihood to be in the 55–64 age bracket than the national study. Median household income reported in the four-county study area for second home owners was $208,330; for residents, $74,416.

Social Indicators

The questionnaire asked second home owners to indicate the reasons why they purchased a second home in the study area. Allowing for multiple responses, second home owners indicated most frequently that it was due to the availability of recreational amenities (83 percent) followed by the proximity to ski resorts (73 percent) and the scenery and surroundings (72 percent). Some 49 percent indicated they had purchased their second home for the investment potential; 14 percent of second homes were being used as full-time rentals and 32 percent as part-time rentals; while 50 percent of usage was by owner, family, and friends. Second home owners were more likely to shop locally (0–10 miles), while local residents indicated they were more likely to shop in the “Extended Region” (30+ miles) including the Front Range (Denver, Colorado) area.

Both second home owners and local residents indicated similar recreational interests with 79 percent of residents and 82 percent of non-residents indicating their favorite activity as being walking and jogging. Popular among both groups was downhill skiing (72 percent resident, 79 percent non-resident), hiking (79 percent resident, 75 percent non-resident) and mountain biking (52 percent resident, 45 percent non-resident). When asked to assess the quality of the recreation offerings, 90 percent of the second home owners indicated strong approval of the quality of the recreation opportunities (83 percent of residents indicated the same), 86 percent (73 percent for residents) indicated strong approval for the quality of the parks, trails and open space, with public safety (66 percent) and the appearance of the community (63 percent) being third and fourth in terms of the assessment of quality by second home purchasers.

High on the list of natural resource amenities for second home purchasers were the scenic/ visual qualities of the study area (95 percent), the quality of the air (95 percent), the quality of the water (95 percent), the recreational opportunities (91 percent), and the parks and trails systems (91 percent). These values were almost identical to those expressed by the residents with 90 percent of residents indicating the importance of the scenic/visual qualities, 91 percent indicating the air and water quality, 79 percent indicating the recreational opportunities and 78 percent indicating the importance of the parks and trails system.

Economic Indicators

Of importance when projecting the economic impact of second home owners is the pattern of use. The full time household equivalency (FTHE)1 for a single family residence was 29 percent of annual usage and for a condominium, 23 percent. There was no significant difference found in usage either by income level or value of residence. Respondents indicated 41 percent level of use for December–March, 12 percent for April–June, 32 percent for July–August, and 14 percent for September–November.

Of importance in policy development and planning is an understanding of the current and projected future use of second home properties. Some 50 percent of the responding second home owners indicated their housing unit was currently used by “owner, friends and family”, 32 percent that it was used as a part-time rental while 14 percent indicated their unit was part of the full-time rental pool. About 21 percent indicated their unit was used only by the owner.

Regarding future use of second home properties, 47 percent indicated they intended to “increase personal use of their property”, while 44 percent suggested they would “maintain their current level of use.” Regarding increasing the usage by friends and family, 28 percent indicated yes, while 11 percent indicated they intended to retire to the area and use the property as a permanent residence. Some 17 percent indicated they were likely to use the residence in the future as a part-time rental unit while 7 percent indicated they intended to use the residence as a full-time rental property. This finding would suggest that there will be fewer opportunities in the future for local residents and workers to rent such property within the local community.

Economic Base Analysis

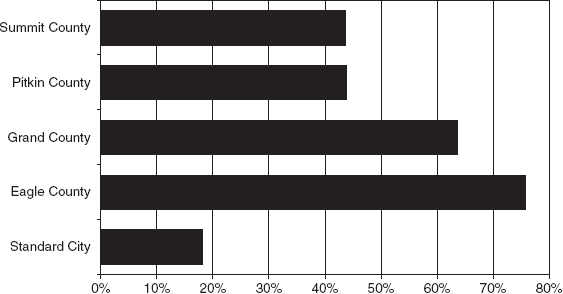

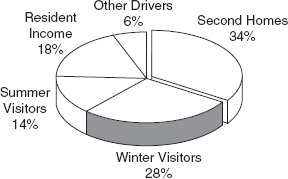

In order to answer the questions related to jobs generated by second homes it was necessary to identify the economic drivers for the study area and so an economic base analysis (Figure 10.3) was conducted (Lloyd Levy Consulting, 2004). This analysis identified that second homes, winter visitors, summer visitors, resident income,2 and other drivers3 were the basic drivers that were generating both basic and secondary jobs. This economic analysis addressed three questions:

Figure 10.3 Economic base analysis

Total spending associated with the economic drivers of the four-county region, including Eagle, Grand, Pitkin and Summit Counties, was estimated to be more than $5.3 billion in 2002. Across the region, second home construction and spending was estimated to be the largest driver, supporting about 31,600 jobs or 38 percent of all jobs. Winter tourism, including skiing, supported about 22,300 jobs, or 27 percent of total jobs, and resident spending of non-local income supported about 13,300 jobs, or 16 percent of total jobs.

(Lloyd Levy Consulting, 2004, p. 14)

Also, this economic analysis projected that across the region construction of housing units 3,000 sq. ft. and larger supports 2,461 direct basic jobs while the construction of housing units less than 3,000 sq. ft. supports 1,612 direct basic jobs. The analysis also projected that spending by second home owners of units less than 3,000 sq. ft. supports 12,796 direct basic jobs while spending by second home owners of units 3,000 sq. ft. or greater accounts for 4,354 direct basic jobs (ibid.).

There are a number of findings from this study that are important for understanding the implications of second home development in the region and for future planning and policy development for the study area. First, the extent to which second homes dominate the housing market limiting the housing stock available to local workers. Second, the uniqueness of this specific study due to the degree of wealth that is being invested in second homes exemplified by both their size and value making it virtually impossible for local residents to afford their purchase. Third, the documentation of shopping and recreational patterns which is driving related amenity development. Fourth, the determination of the degree to which the second home economy serves as an economic driver for the region and the dramatic impact future second home development will have on job creation. And, fifth, the establishment of a methodology that can be used to systematically track this development into the future.

It is important to note that local residents and second home owners both hold similar “values” regarding community amenities; they also indicated similar recreational interests. Both groups indicate they visit or live in the region primarily because of these qualities not because of the potential economic gain of property ownership. Thus, both groups have good reason to protect the area’s resources and the highly rated quality of life the region currently provides. Both groups should be keenly interested in policies and actions that maintain the area’s economic and social well-being.

The “classic” second home owner in this region will, in each of the respective counties, have a median household income of: Eagle, $301,408; Grand, $105,660; Pitkin, $277,500; and Summit, $148,750. Their second home usage would be approximately 90 days per year. They will not show up in population counts, do not vote locally and do not participate in the local workforce. They are predominantly aged 55–64 and may own a 3rd or 4th home.

The “affordable” local resident will, in each of the respective counties, have a median household income of: Eagle, $62,682; Grand, $47,756; Pitkin, $59,375; and Summit, $56,587. Their home usage will be approximately 330–60 days per year and they live in subsidized housing or houses bought while prices were still affordable. They show up in population counts, vote locally and participate in the local workforce. They may have lived in the area for a long time and are predominantly aged 30–75+.

The workers in the four-county study area employed in the second home basic industry and their families require housing and a wide range of private and public community services. The workers providing these services, in turn, have the same needs. Typically, in a second home resort community there is initial development and maturation of a traditional tourism industry. However, over time, second homes become a large and often dominant part of the physical, economic, and social landscape. Their development creates a demand for workers above that of the traditional tourist industry, especially in housing construction but also in their maintenance, operation, and use. As the number of second homes increase, the demand for workers to support the second home industry increases as well. Knowledge of the effects of this industry is essential to resort community planning including understanding and anticipating the secondary or “multiplier” effects. To not understand the effects can lead to shortages and to major conflicts among the users of the various resources of the area.

Second homes take up large amounts of land in Colorado mountain resort areas where developable land is already in short supply. As a result, the value of second homes and the surrounding land rise above that normally paid for worker housing. As their numbers increase, and the land available for development decreases, a dilemma is created. Second homes have generated the need for more workers, but the rise in property values and subsequent housing costs have made it difficult for the workers to live within a reasonable distance of their place of work.

Traditionally, residential homes and their neighborhoods have provided workers with a decent home and adequate community services. However, second homes are different in that they are not just residences, but an industry creating a demand for workers. Second homes drive up property values, including residential housing for workers. Because of this, it becomes especially important for elected officials and community planners to understand and estimate the secondary effects of second homes in tourist-based economies. With this information, policies can be developed by local governments to protect the natural amenities and provide for the social needs of citizens with each new development and to influence the growth in the economic drivers themselves. To ignore this information concerning second homes within the study region and beyond, casts social and economic fate to the wind.

There are clearly many additional questions that this second home research has raised. The foremost is addressing specifically how this information can be effectively transmitted to community planners and public policymakers for its effective use in growth management and community planning. Follow-up studies for this region will certainly include the addition of other counties to the study area and reanalysis of the property records to include an assessment of the conversion of units that remove them from the local rental pool. Economic changes related to the trend of second homeowners retiring to the area will be analyzed and the survey and economic analysis used to measure changing trends will be updated. The economic drivers will be reassessed and projections of job creation and shortages reanalyzed. All of this information will continually be analyzed for planning and policy implications for the region and discussion will be held at all levels to ensure broad citizen engagement in decisions about the future of the region.

1 Full time household equivalency (FTHE) was a measure created by the NWCOG Steering Committee to describe the extent to which a housing unit was occupied on a full-time basis by its owner.

2 Resident income includes retiree income, transfer payments, dividends, interest and rent.

3 This includes mining, manufacturing, agriculture and Interstate I-70 thru-traffic expenditures.

Andereck, K. L. and Vogt, C. A. (2000) ‘The relationships between resident’s attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options’. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 27–36

Blevins, J. (2004) ‘Resort sales on a record pace: Colo. real estate deals may surpass 5.7 billion high in 2000’. Denver Post, 4 July, p. K–08

Cho, S.-H., Newman, P. K. and Wear, D. N. (2003) ‘Impacts of second home development on housing prices in the Southern Appalachian Highlands’. Review of Urban and Regional Development Studies, 15(3), 208–25

Clifford, H. (2002) Downhill slide: Why the corporate ski industry is bad for skiing, ski towns and the environment. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books

Colorado Ski Country USA (2004) Season report 2003–2004. Denver, CO: Colorado Ski Country USA

Coppock, J. T. (ed.) (1977a) Second homes: Curse or blessing? Oxford: Pergamon Press

Coppock, J. T. (1977b) ‘Issues and conflict’. In J. T. Coppock (ed.) Second homes: Curse or blessing? Oxford: Pergamon Press, pp. 195–215

CSDO (2003) Ski county employment estimates. Denver, CO: Colorado Department of Local Affairs, State Demographer Office

Curry, P. (2003) ‘Second to none’. Builder, 26(12), 218–26

Egan, N. (2000) ‘Scaling up’. Urban Land, August, pp. 94–101

Francese, P. (2003) ‘Top trends for 2003’. American Demographics, 24(11), 6

Gill, A. (2000) ‘From growth machine to growth management: The dynamics of resort development in Whistler, British Columbia’. Environment and Planning A, 32, 1083–1103

Gill, A. and Williams, P. (1994) ‘Managing growth in mountain tourism communities’. Tourism Management, 15(3), 212–20

Hall, C. M. and Müller, D. K. (eds) (2004a) Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground. Clevedon: Channel View Publications

Hall, C. M. and Müller, D. K. (2004b) ‘Introduction: Second homes, curse or blessing? Revisited’. In C. M. Hall and D. K. Müller (eds) Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground. Clevedon: Channel View Publications, pp. 3–14

Korça, P. (1998) ‘Resident perceptions of tourism in a resort town’. Leisure Sciences, 20(3), 193–212

Lipsher, S. (2002) ‘Breckenridge, Colo.: Ski resort unveils expansion’. Denver Post, 11 September. Retrieved 1 November 2011 from http://www.libraryo.com/article.aspx?num=91368027

Lloyd Levy Consulting (2004) Job generation in the Colorado Mountain Resort economy: Second homes and other economic drivers in Eagle, Grand, Pitkin and Summit Counties executive summary. Denver, CO: Levy, Hammer, Siler, George Associates

McGehee, N. G. and Andereck, K. L. (2004) ‘Factors predicting rural residents’ support for tourism’. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131–40

Müller, D. K., Hall, C. M. and Keen, D. (2004) ‘Second home tourism impact, planning and management’. In C. M. Hall and D. K. Müller (eds) Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground. Clevedon: Channel View Publications, pp. 15–32

Perdue, R. R. (2003) ‘Stakeholder analysis in Colorado ski resort communities’. Tourism Analysis, 8(2), 233–36

Perdue, R. R. (2004) ‘Sustainable tourism and stakeholder groups: A case study of Colorado ski resort communities’. In G. I. Crouch, R. R. Perdue, H. J. P. Timmermans and M. Uysal (eds) Consumer psychology of tourism, hospitality and leisure (Vol. 3). Cambridge, MA: CABI Publishing, pp. 253–64

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T. and Allen, L. R. (1990) ‘Resident support for tourism development’. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(4), 586–99

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T. and Kang, Y. S. (1999) ‘Boomtown tourism and resident quality of life: The marketing of gaming to host community residents’. Journal of Business Research, 44(3), 165–77

Phillips, M. (1993) ‘Rural gentrification and the processes of class colonisation’. Journal of Rural Studies, 9(2), 123–40

Smith, V. L. (2001) ‘Sustainability’. In V. L. Smith and M. Brent (eds) Hosts and guests revisited: Tourism issues of the 21st Century. New York: Cognizant Communications, pp. 187–200

Timothy, D. J. (2004) ‘Recreational second homes in the United States: Development issues and contemporary patterns’. In C. M. Hall and D. K. Müller (eds), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground. Clevedon: Channel View Publications, pp. 133–48

US Census Bureau (2005) ‘State and country quick facts: Summit County, Colorado’. Retrieved 1 November 2011 from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/08/08117.html

Weaver, D. (2008) Sustainable Tourism: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 1–17