Globalization has resulted in the emergence of large tourism corporations whose influence on the destinations in which they operate have been referred to as “the corporatization of place” (Rothman, 1998). Paradoxically, as the commercial power and market reach of these large tourism corporations have expanded, so has the mix of local authorities and non-government organizations (NGOs) that have emerged to contest or modify their actions (Norcliffe, 2001). This has led to calls for more collaborative approaches to engagement by corporations and destination stakeholders. The way in which these relationships unfold may be central to establishing not only the corporation’s social license to operate (Cunningham et al., 2003), but also the overall destination’s sense of place (Williams and Gill, 2004).

This chapter provides a framework for understanding relationships between tourism corporations and their destination stakeholders. While a rapidly growing literature exists on stakeholder aspects of strategic planning and business management (Hillman and Keim, 2001; Prahalad and Hamel, 1990; Svendsen, 1998), as well as tourism-related collaborative planning (de Araujo and Bramwell, 1999; Getz and Timur, 2005; Jamal and Getz, 1995; Williams, Penrose, and Hawkes, 1998), there has been little attempt to understand how interactions between corporations and local institutions are implemented and how they evolve in tourism destinations (Flagestad and Hope, 2001). Similarly little has been published concerning how these interactions occur in the context of corporate–civil society stakeholder relationships. Consequently, this paper uses the framework to describe evolving corporate–civil society relationships in the tourism resort destination of Whistler, British Columbia, Canada. The findings provide insights into how such stakeholder interactions affect corporate social license to operate, as well as destination sense of place.

The paper’s framework for examining corporate–community stakeholder relationships (Gill and Williams, 2006) is built on several theories discussed in the strategic management literature. In particular, it includes elements of stakeholder theory (Svendsen, 1998), the resource-based view of the firm (Wernerfelt, 1984), corporate social responsibility (Carroll, 1999), corporate environmentalism (Berry and Rondinelli, 1998), and social license to operate (Cunningham et al., 2003). Elements of these paradigms pertinent to the paper’s overriding corporate-community stakeholder framework are briefly described in the context of mountain tourism destination management.

Stakeholder Theory

Svendsen et al. (2002, p. 1) contend that

[in] a rapidly globalizing, knowledge-based economy, sources of value creation in business are shifting from tangible assets such as land and equipment, to intangibles such as intellectual and human capital.

Primary stakeholders include shareholders and investors, employees, resource suppliers, customers, community residents, as well as groups speaking for the natural environment (Hillman and Keim, 2001). Clarkson (1995, p. 106) identifies public stakeholder groups as being those “governments and communities that provide infrastructures and markets, whose laws and regulations must be obeyed, and to whom taxes and other obligations may be due”. A seminal principle of stakeholder theory relevant to this research is that a corporation is given the social license to operate by virtue of its social contract with external stakeholders (Robson and Robson, 1996). Effective management of these relationships “can constitute intangible, socially complex resources that may enhance firms’ abilities to out-perform competitors in terms of long-term value creation” (Hillman and Keim, 2001, p. 127).

Resource-Based View of Firm

The competitiveness of firms is derived from their distinct tangible and intangible assets (Wernerfelt, 1984). When these resources are unique and/or cannot be replicated by competitors, they produce competitive advantages (Barney, 1991). Priority access to raw materials such as labour, energy, and land are examples of tangible resources that may provide competitive advantage. Examples of intangible resources that can contribute to a firm’s competitiveness include its favorable reputation with consumers, responsive corporate culture, and goodwill with suppliers and customers. Acquiring on-going access to such resources may involve considerable investments of human capital in developing positive relationships with external stakeholders. Such engagements can build value with stakeholders (Hart, 1995; Jamal and Getz, 1995) who may be the gatekeepers to resources that firms need (Svendsen et al., 2002). They can also help reduce corporate risks by: introducing more effective management strategies; reducing the chances of adverse public relations; and reinforcing the firm’s social license to operate in the marketplace (Harrison and St. John, 1996).

Corporate Environmentalism and Social Responsibility

Corporate environmentalism emphasizes the importance of responding to consumer and political pressures for proactive environmental protection. Competitive advantage is gained by pursuing management strategies which avert the costs of conflict, decrease the need for government regulation and intrusion, and improve the economic efficiency of production processes (Banerjee, 2001; Delmas and Terlaak, 2001; Gibson and Peck, 2001; Lyon, 2003; Parker, 2002). Successful corporate environmentalism initiatives focus on building greater communication and understanding between the firm and its internal and external stakeholders.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) concepts and practices extend from corporate environmentalism models (Banerjee, 1998). They emphasize solving and preventing environmental and social problems through collaborations that benefit both businesses and stakeholders (Cragg, 1996). Proponents of CSR believe that such practices facilitate greater cross-fertilization of thinking which leads to more creative and actionable management strategies (Hart, 1995).

Social License to Operate

Traditionally, corporations viewed compliance with existing regulatory requirements as their sole legal and social responsibility (Cunningham et al., 2003). Adherence with existing environment, social, and labor requirements was primarily done to avoid liability penalties or to meet moral and social obligations (Wright, 1998). The prevailing philosophy was that going beyond compliance should occur only in situations of “self interest” (Porter and van der Linde, 1995). However, growing regulatory regimes and increasingly litigious civil societies in some jurisdictions have led corporations to consider their social obligations as extending beyond solely meeting legal requirements (Evans, 2001). Corporate leaders consider acquiring approval to function in accordance with community expectations as their social license to operate. While the levels of corporate performance expected by these community stakeholders may extend well beyond minimal legal requirements and be economically challenging, they represent yet another factor in shaping decisions concerning the strategic positioning of some businesses. While there is limited consensus on what social license to operate entails in practice, there is growing recognition of its importance as a corporate strategy. A series of damaging encounters between large corporations and civil society (e.g. Connor and Atkinson, 1996; Moore, 2001; Neale, 1997; van Yoder, 2001), caused by private sector misreading of the terms of their social license to operate, has stimulated a growing corporate interest in establishing stronger relationships with grass roots community stakeholders. As corporations learn more about the influence of civil society organizations as “community gatekeepers”, so has the concept of social license to operate grown in relevance to these businesses. The concept may have particular relevance to corporations operating in tourism destinations where many functions critical to the visitor’s experience are affected by stakeholders external to individual corporations (Flagestad and Hope, 2001; Murphy and Murphy, 2004).

In a “Western” tourism destination management context, this means that corporations may be granted a social license to operate by different stakeholders (e.g. regulators, employees, customers, investors, suppliers, or local communities), and that each of these parties can revoke the organization’s privileges to operate at any time. Indeed it is not unusual for stakeholder relations with such corporations to ebb and flow as the destination evolves through its various stages of development.

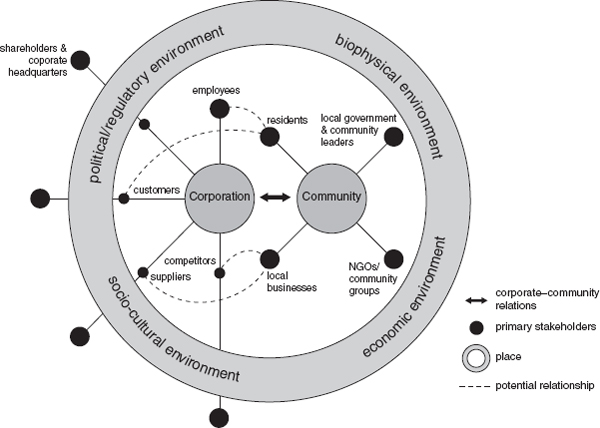

Based upon the preceding concepts and an understanding of tourism destination management strategies, a conceptual model of corporate–tourism destination stakeholder relationships is presented in Figure 13.1. In this model, corporation and community entities have networks of stakeholders that operate within the context of a destination characterized by the area’s unique economic, political/regulatory, socio-cultural, and biophysical environments. The primary corporate stakeholders include customers, employees, suppliers, competitors, and shareholders. With the exception of employees, the majority of these stakeholders are primarily located outside the community, although this concentration will vary with each situation. The community’s primary stakeholders are local government and community leaders, residents, local businesses, NGOs, and other community groups. While Figure 13.1 simplifies the complexities of the various interactions between these stakeholder groups, the model suggests (dashed lines) some possible linkages between the various actors. For example, employees are in many instances residents. Other residents may be customers or even shareholders. Local businesses may function as suppliers or competitors.

Figure 13.1 A place-based model of corporate-community relationships

The model presents a generic situation. There are a number of distinct features that characterize North American mountain resort destinations, including:

While the corporation represents the main economic driver upon which the community depends, it is also dependent on the community. The community not only provides the regulatory approvals for its development plans, but also helps to maintain the high quality environment and hospitality levels needed to satisfy the company’s customers. The ability of the corporation to meet these requirements is dependent to a large degree on how well it establishes a social license to operate with relevant stakeholders in the community. Key destination stakeholders that can act as gatekeepers in providing a social license to operate include civil society groups such as environmental non-government organizations (ENGOs). To a large degree, the relative amounts and types of power distributed amongst these destination stakeholders determine the character of engagement between corporate and community groups as well as the nature of environmental management decisions taken.

Evolving Corporate-Civil Society Relationships in Whistler, BC

The following case study illustrates the ways in which a large resort development and management corporation has engaged with ENGOs and other local stakeholders to ensure the continuance of its social license to operate on environmental management matters. It is based on research involving key informant interviews with a purposive sample of 27 interviewees comprised of community members (9), ENGO representatives (14), and personnel from Intrawest corporation’s Whistler–Blackcomb (W-B) operations (4) in Whistler, British Columbia (Marcoux, 2004; Xu, 2004). These key informants were selected based on their availability, research subject matter experience, and functional position within the key stakeholder groups (e.g. leaders, managers, and participants in environmental activities in their respective organizations).

A review of stakeholder, resource-based view of the firm, corporate social responsibility, and social license to operate literature guided the development of the standardized survey instruments used to collect the primary data for the study. In these questionnaires a combination of standardized semantic differential, Likert scale, and open-ended questions were used. The semantic differential and Likert scale questions solicited overall opinions on key issues. Accompanying open-ended questions enabled respondents to elaborate on more specific aspects of their responses to those same questions. In addition, customized questions more specific to each stakeholder group (e.g. W-B, ENGO, and broader community representatives) were employed to probe other key dimensions of the relationship between W-B and the Association of Whistler Area Residents for the Environment (AWARE). Themes explored in the questionnaires related to priority environmental goals and objectives of the participating organizations, critical criteria, and motivators for establishing stakeholder relationships, engagement processes, and lessons learned from stakeholder involvement (e.g. perceived benefits and challenges associated with engagement).

Informants were personally interviewed by members of the research team during the summer (August) and the winter (December) of 2003. Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. Upon completion of this process, the interviewees were asked to review their individual transcripts for accuracy and offer further elaboration on commentary they had provided. Using their edited responses as a base, overriding similarities and differences in stakeholder responses were identified on a question by question basis. For the purposes of this research paper, only the responses of ENGO and W-B interviewees were used to inform the findings presented. In combination, their responses provide insights into the evolving role and impact that stakeholder relationships play in shaping both corporate and ENGO environmental activities in Whistler.

Whistler is widely recognized as one of the most frequented ski destinations in the world. Two massive ski mountains, as well as thousands of hectares of pristine backcountry, challenging alpine terrain, massive glaciers, and crystal clear lakes provide the physical backdrop for the destination’s pedestrian village and related community activities. About 80 percent of the destination’s 10,000 permanent residents are employed servicing the town, small businesses, and Intrawest, the largest corporation in the community. In the 1999–2000 ski season, Intrawest’s Whistler-Blackcomb (W-B) ski operation generated more than two million skier visits, making it the most heavily used ski area in North America (Intrawest, 2003). These visitors provided the impetus for employing about 13,800 people in Whistler and 30,000 people in the region (RMOW, 2002).

W-B was indisputably the main economic producer in Whistler, responsible for generating the lion’s share of the destination’s business. By virtue of its influence on the drivers of employment, prices, growth, and material standards of living in the destination, it was also capable of using tremendous “allocative” power (Ashworth and Dietvorst, 1995; Flagestad and Hope, 2001) to leverage political decisions in its favour. This power is particularly strong in tourism places which are focused on using economic performance to measure community well-being.

Intrawest’s Evolving Corporate Environmentalism

At the time of this study Intrawest’s development portfolio included 14 mountain resort operations in a variety of destinations across the globe. Its flagship resort development was located in Whistler and operated by a locally based W-B management team. The W-B group had long recognized that the success of its operations was dependent upon an ability to sustain the area’s natural environment. To this end, one of W-B’s key objectives was to “continue to improve our commitment to sustainability and environmental excellence” (Intrawest, 2003). Its level of commitment and approach to environmental management evolved over time.

Prior to 1992, Intrawest’s W-B management activities focused more on conducting due diligence practices that ensured the safety of mountain guests and staff than on addressing environmental issues. However, an unanticipated on-mountain oil spill in 1992 alerted the company to the importance of having a sound environmental management system in place – one that acknowledged that “regulatory compliance was not sufficient” (W-B respondent #1) to prevent accidents capable of creating significant environmental damage. In response to the incident, they immediately committed W-B to addressing the spill’s effects and putting standards in place which would ensure that such an environmental disaster would not happen again. In addition, they provided community stakeholders with timely and transparent reports on the incident’s impacts as well as the mitigating actions they were taking. Not only did the spill provide an early lesson to W-B concerning the need for a comprehensive environmental approach to its business operations, but it also offered them an insight concerning the importance of maintaining a strong social license to operate with key stakeholders in the community.

In response to the oil spill incident, W-B created its first comprehensive environmental management system (EMS) to guide its mountain operations in 1994 (Todd and Williams, 1996). Over the years, this EMS gradually evolved to a point where it incorporated many of the principles and guidelines for sustainability as outlined by the National Ski Area Association’s Sustainable Slopes Charter (NSAA, 2000) and The Natural Step Framework – an environmental management framework that helps organizations and communities understand and move towards sustainability (Nattrass and Altamore 2003). These principles guided W-B in its planning, design, construction, operation, internal education, and outreach activities.

Linkages with community stakeholders were continually nurtured especially with respect to new planning, education, and outreach programs. For instance, W-B was initially involved as an “early adopter” of the Natural Step Framework, and the subsequent development of Whistler 2020: Moving Toward A Sustainable Future, the destination’s comprehensive sustainability plan (RMOW, 2004). It also collaborated with several community and non-government organizations to implement specific parts of the destination’s ‘Whistler: It’s Our Nature’ program (Nattrass and Altamore, 2003). This initiative was operated by a local ENGO and supported local businesses, households, and other organizations in adopting more sustainable practices.

Associated with their activities, W-B had an environmental vision, created to guide current practices with respect to environmental matters. The stated vision was:

To contribute to the goal of sustainability by developing, through its environmental management system, the highest level of environmental stewardship in the North American mountain resort industry. (W-B respondent #1)

Because of W-B’s immediate proximity to the resort destination, many of the company’s environmental strategies not only influenced the organization’s internal stakeholders, but also affected surrounding community groups and activities. Simultaneously, the ultimate effectiveness of many of W-B’s strategies depended on the support of local stakeholders. Specific initiatives that required community stakeholder engagement and support included programs linked to fish and wildlife management, bear and marmot habitat preservation, glacier protection, water and energy conservation, environmental education, and social event sponsorship. W-B won several environmental awards and much community recognition for its leadership role in nurturing strong corporate–community relations with respect to citizenship and environmental stewardship.

Stakeholder Management

W-B defined stakeholders as “those individuals or groups who live or work in the municipality of Whistler and who affect, or are affected by, our mountain operation activities” (W-B respondent #2). They included Whistler residents, businesses, local government institutions, tourism marketing organizations, and non-governmental agencies. Two overarching groups comprised W-B’s primary environmental stakeholders. They were:

To illustrate W-B’s stakeholder management approach, this paper describes the corporation’s engagement philosophies and methods related to AWARE.

Evolving Corporate Engagement with AWARE

AWARE was originally formed in 1987 to pressure local government to enact a recycling program. Its success in this venture evolved into grander responsibilities associated with being a leading community advocate on numerous other environmental issues. These included a very controversial proposed golf course development which it said would significantly damage the ecological integrity of the area. Although the development project eventually went ahead, AWARE gained a large degree of community credibility and local government legitimacy based on the way it conducted itself during this process (Xu, 2004).

AWARE played a significant role in shaping the destination’s informal response to a variety of environmental management issues. Depending on the organization’s collective capacities, as well as the specific issue being addressed, AWARE fulfilled a variety of functions. These reflect typical ENGO roles identified in the literature (Burns, 1999; Jamal, 1999; Lama, 2000) and included:

AWARE’s ability to achieve its objectives was based largely on its credibility and legitimacy as an environmental champion. As a non-producer community group, it had only a small fraction of the allocative power (Ashworth and Dietvorst, 1995) possessed by W-B and other destination producers. However, in contrast it carried a substantial level of “authoritative” power. Growing concern in Whistler about sustainability issues helped to position it as a source of credible knowledge and as the leading “environmental watchdog” for local residents. Consequently, its approval was frequently sought by both government and developers in matters related to activities that impact on the destination’s environment.

Drivers of Corporate–ENGO Engagement

Several potential drivers motivate the establishment of corporate–ENGO relationships (Elkington and Fennell, 1998). From a business perspective, a company may enter into such partnerships in order to build a brand image which increases its credibility with markets and strategically important stakeholders (Bendell, 2000). Specifically, such involvement can influence public opinions concerning corporate environmental and social performance (Svendsen, 1998). Moreover, by working with ENGOs, a company can use “outside” perspectives to improve its approach to “inside” practices (Harrison and St. John, 1996). ENGOs can be a valuable source of new ideas and critical thinking. Inviting them to participate in business planning processes either as advisers or board members can increase the effectiveness of corporate initiatives (Rondinelli and Berry, 2000). Furthermore, financial and natural resource savings as well as eco-efficiencies can be achieved through partnerships with environmental groups due to their expertise and ability to mobilize volunteers (D. E. Murphy and Bendell, 1997). Partnering with environmental groups can generate good publicity and result in less protest or government intervention in corporate practices (Harrison and St. John, 1996).

Other drivers contribute to increasing the willingness of ENGOs to collaborate with businesses. These include growing recognition that:

The extent and type of engagement between W-B and its environmental counterparts varied depending upon the perceived power and legitimacy of the stakeholder as well as the urgency of the issue being addressed. In the mid-1980s W-B tended to act in isolation of the community. “The company had their own design panel, their own set of rules and could do things that other people couldn’t” (W-B respondent #3). As the power and legitimacy of some of the more established ENGOs in Whistler grew, so did W-B’s interest in working with them. This was especially apparent with the largest and highest profile of Whistler’s ENGOs: AWARE. Because of AWARE’s informal position as the community’s “environmental watchdog”, W-B paid particular attention to it on environmental issues. This interest in engagement increased as the company’s developmental activities grew.

While there were points of antagonism between AWARE and W-B in previous years, over time the relationship shifted from being primarily adversarial to more collaborative and solution seeking in character. While some critics perceived AWARE’s agenda as being co-opted by W-B’s priorities, proponents of the relationship believed that it brought together resources and talents that could “galvanize and connect the community around initiatives that can make the destination a more desirable place to live and visit” (ENGO respondent #1). Other AWARE respondents also felt that such an approach increased the efficiency and effectiveness with which decisions and actions concerning environmental management could be made.

Overall, W-B informants claimed that the most important benefits of establishing and nurturing stakeholder relationships with AWARE (and other similar organizations) were linked to: enhancing the image and credibility of the company with respect to its environmental activities; and, subsequently increasing the efficiency with which it obtained formal approvals to proceed with proposed development and management activities (Table 13.1). Conversely, AWARE stakeholders claimed that the most important advantages obtained from their engagement with W-B included: increasing their ability to “leverage” the resources needed to address environmental problems; and, being able to address solvable issues in a non-bureaucratic and pragmatic fashion.

Engagement Strategies

Accurately identifying stakeholders and creating the circumstances suited to effective dialogue with them are keys to successful engagement (Cragg, 1996). Specific strategies needed for effective and imaginative engagement include: establishing trust, encouraging inclusiveness, ensuring responsiveness, and demonstrating commitment.

Table 13.1 Top perceived drivers of W-B-ENGO stakeholder relationships

| Perceived Importance of Drivers of W-B’s Engagement with AWARE | Perceived Importance of Drivers of AWARE’s Engagement with W-B |

• Desire for enhanced credibility with government, community and market (High) |

• Desire for greater leverage in addressing “solvable” problems (High) |

• Need for increased efficiency in obtaining development approvals (High) |

• Search for less bureaucratic and action-oriented solutions (High) |

• Desire to “head off” negative public confrontations (High) |

• Need for more resources (e.g. funding, technical and management expertise) (Medium) |

• Interest in cross-fertilization of ideas (Medium) |

• Desire to build a problem-solving as opposed to antagonistic community culture (Medium) |

• Interest in educating key stakeholders about rationale and strategies for environmental activities (Medium) |

• Interest in cross-fertilization of ideas (Medium) |

While some companies formalized strategies for engaging stakeholders, W-B provided little formal clarity in this regard. Their philosophy was based on an understanding that:

They operationalized this philosophy, by incorporating various ingredients of effective stakeholder engagement into their actions on a situational basis.

Trust

Trust is needed for engagement strategies to be effective. It is most often nurtured and maintained by open interaction and transparency between the engaged groups. Trust is risked when the engaged parties fail to be transparent about how issues are being handled and/or not forthcoming about sharing information relevant to the problem. Transparency can be characterized by honesty, integrity, and openness. It is one of the key indicators of a good relationship between a corporation and its stakeholders.

Transparency

Managers at W-B believed that transparency was a “key factor for gaining community support” (W-B respondent #2). For instance, a senior W-B executive met regularly with other leaders of the community in a group called One Whistler. This senior level group meetings addressed strategic and more pervasive destination development and management issues that required the operational attention of community stakeholders. Issues and proposed actions created by W-B and other organizations that appeared contradictory to the values of the resort community were addressed in an open and transparent fashion. This kept W-B and its community leaders (including AWARE) abreast of emerging issues and concerns early on so that mutually beneficial solutions could be created prior to controversial events happening.

Inclusiveness

Inclusiveness refers to the level of involvement that organizations give their stakeholders in decisions that affect them or that they can affect. For W-B, inclusion did not necessarily imply direct stakeholder participation in the making of its decisions. However, it did infer that the perspectives of all those with a stake in the decision’s outcome would be included in the process of arriving at the selected course of action.

Establishing inclusive relationships with Whistler’s growing list of community stakeholder groups was increasingly challenging. W-B used a networking approach to determine who was included in the engagement process. In this approach they identified which groups were related directly to the issue as well as those who are indirectly impacted via other exchanges, communications and actions. For instance, AWARE had relationships with its members, and these individuals have interactions with other constituencies such as their families, retailers, financial institutions, who may have been engaged in other relationships with W-B. The approach de-emphasized the centrality of W-B in addressing environmental matters alone, and encouraged communication, support, and actions with stakeholders from the broader community. This is particularly important in destination communities where the entanglements amongst individuals who are involved in many different community organizations can be significant.

By understanding the interrelationships and communication patterns that existed within and between destination stakeholder organizations, W-B strategically selected those alliances which created the greatest leverage for its activities. Its pragmatic approach to determining whom and how specific stakeholders were included is situational in character. Depending on the issue, the level and type of inclusion ranged from formally engaging a wide range of stakeholders in public forums, meetings, and workshops to total immersion of some specific interest groups in targeted activities of the company. While approaches varied with the intent of the engagement, W-B suggested that the more they place stakeholders in the reality and context of the management problem, the greater the probability that stakeholders would create solutions that met with corporate and community approval. They suggested that such approval (i.e. social license to operate) made implementation of potential options more feasible.

Responsiveness

Responding to stakeholder issues in a proactive, timely, and appropriate manner built trust and credibility for W-B. In order to “win the hearts and souls of the community we must demonstrate an interest in community issues and ‘walk the talk’” (W-B respondent #4). For instance, by being pro-active and responsive to the community’s overriding comprehensive sustainability initiative, W-B was able to secure a valuable social license to operate from many of the destination’s most influential environmental stakeholders. This “social capital” was invaluable in helping the organization negotiate approval for a range of other development initiatives in the community.

Commitment

The success of any relationship depends upon the level of commitment of all participants. Having common or complementary goals provides the basis for commitment. Once these goals have been established, participants are more apt to move toward the achievement of these milestones in a collaborative manner. While stakeholders may have asymmetrical motivations, goals, and organizational capacities behind engagement, commitment to making the process work increases when the purpose of the interaction is attractive to both. This is more apt to occur if the parties share certain cultural values and fundamentally respect each other’s legitimacy and integrity.

For W-B and AWARE, the common goals were environmental conservation and the economic success of the resort. The nature of the ski industry demanded that W-B capitalize on the natural environment within which it operated. At the same time, W-B recognized that protecting the quality of the region’s environment was a value held by AWARE and other community stakeholders. “It is the glue that brings W-B together with many of its stakeholders” (AWARE respondent #1). Despite missteps along the way, W-B’s environmental initiatives became a means of bringing the company and AWARE together on a variety of planning fronts. AWARE stakeholders agreed that W-B was astute and possessed good business sense when it came to involving the community in decisions that affected them. “They intuitively understand the need to protect the environment” (AWARE respondent #2).

Situational Applications

An example of W-B’s situational application of the preceding ingredients of effective stakeholder engagement was demonstrated with respect to a ski area expansion project proposed by the company in the Piccolo-Flute backcountry area of Whistler Mountain. When initially announced by W-B, the development created considerable controversy amongst local stakeholders who were emotionally attached to the site. Locals felt that this pristine terrain should remain relatively inaccessible to visitors. In response to initial concerns, W-B invited local advocacy groups (including AWARE) to discuss the intent and potential options for utilizing the area in a sustainable fashion. Despite W-B being within its legal rights to develop this area, an excursion and on-site workshop activities were organized by W-B to develop clear channels of communication concerning the intent of the project, as well as to identify key issues of conflict that had to be addressed before any social license to operate would be approved. Based on considerable front-end dialogue, local stakeholders identified and supported more favorable non-mechanized backcountry development options that protected the pristine character of the area.

A key to the success of this initiative was a desire on the part of W-B to engage AWARE and other parties in a two-way dialogue about the project. This exchange could only occur if both parties were willing to participate, and had the organizational capacity to engage in such a discourse. W-B had in place personnel with the social and technical skills needed to guide a proactive dialogue. Similarly, AWARE’s membership included people with capable communication and negotiation talents.

W-B’s transparency in sharing its intent for the area, its inclusiveness of AWARE and other stakeholders with the capacity and willingness to participate in the dialogue, its responsiveness to their concerns, and its commitment to reinforcing shared environmental and socio-cultural values in the area helped it achieve commercial goals and reinforced its social license to operate within the destination community.

While stakeholder engagements between W-B and AWARE varied in type and intensity over the years, participants in these relationships identified a range of perceived benefits emanating from the interactions. Those benefits contributing to W-B’s social license to operate in Whistler are summarized in Table 13.2. Overall, both W-B and ENGO respondents agreed that such engagements had been most effective at:

This chapter described the overriding motivations, strategies, and benefits associated with W-B’s stakeholder engagement initiatives with ENGOs in Whistler. While there were challenges associated with these relationships in the past, overall engagement initiatives became less confrontational and more constructive in character. Several factors help to explain this situation. These are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Table 13.2 Perceived benefits of W-B-ENGO stakeholder engagement

| Potential benefits of stakeholder engagement | Estimated level of perceived benefit amongst W-B respondents* | Estimated level of perceived benefit amongst ENGO respondents* |

Improved environmental decision making |

||

• Generation of more innovative alternatives |

Moderate |

High |

• Consideration of greater range of potential effects |

High |

High |

• Creation of “win-win” solutions |

High |

Moderate |

Improved community trust and commitment |

||

• Quicker response to planning approval requests |

Moderate |

Moderate |

• Increased community awareness with respect to potential |

High |

High |

outcomes |

||

• Increased credibility and support for outcomes (social licence to operate) |

High |

High |

Common vision and goal |

||

• Increased opportunities for shared environmental values |

High |

High |

• Improved knowledge transfer between employees and community stakeholders |

Moderate |

High |

• Enhanced opportunities for synergistic community actions |

Moderate |

High |

Positive contribution to “triple bottom line” |

||

• Reduced costs of liability and risk containment |

High |

High |

• Reduced costs of gaining development approvals |

Moderate |

Uncertain |

• Reduced employee retainment costs |

Moderate |

Uncertain |

• Strengthened reputation and visibility of destination and company amongst key stakeholder groups |

High |

High |

*Estimates based on qualitative interpretation of overall responses.

Connection to Place

The lion’s share of W-B’s full-time employees lived and worked in Whistler. Consequently, many of them shared concerns and interests similar to those raised by other community businesses and residents. Whistler’s past community visioning processes identified a remarkable level of consensus amongst business and community-based stakeholders concerning local environmental, social, and economic priorities for the destination. As such, it is less likely that W-B’s employees would willingly make decisions that were contrary to the commonly held environmental values of the community.

It’s a little different in Whistler, because senior managers live here, so they are part of the community. Resort managers must live in the community, join the social club, and send their children to the local school. Otherwise they are the folks from out of town. (W-B respondent # 2)

Corporate-Community Stakeholder Entanglement

The “web of entanglement” between organizations, businesses, and residents in Whistler was pervasive and complex. Local residents frequently had dual roles within the destination (e.g. working for the company to protect its competitive natural assets, while living a lifestyle built on access to the same environment attributes). This duality offered

broader perspectives on environmental and social impacts and the consequences of development. It strengthens opportunities to reinforce values and actions of importance in both corporate and community life in a genuine and forceful manner. Additionally, it helps establish levels of trust and respect that carry over into actions in corporate and community spheres. (AWARE respondent #2)

Community Trust and Respect

At a basic level, personal contact and mutual trust between W-B employees and AWARE stakeholders were critical ingredients in forging successful engagement initiatives. Through such engagements the participants shared different concepts, learned other perspectives, and refined their own viewpoints on appropriate strategies. Such dialogues also provided opportunities to scrutinize the resolve and commitment of their counterparts to achieving commonly defined goals. This led to enhanced personal credibility and respect – something beyond their respective roles as corporate managers or ENGO leaders. While corporations are still driven by “bottom-line” operating mandates, the approaches they used for decision making can potentially lead to better outcomes that have the backing of a social license to operate granted by community stakeholders.

Evolving Structures and Actions

As competition in the global tourism marketplace continues to increase, so does the need for corporate–community stakeholder partnerships, alliances, and dialogue (KPMG Management Consulting, 1995). As never before, there is a need to bring together the allocative power of corporations with the authoritative power of community stakeholders in order to compete on the world stage (Scholzman and Tierney, 1986). An emerging outcome of such processes of engagement in Whistler was an evolution in the character and actions of the engaged parties and the institutions they represent. While initial engagements between W-B and its community partners often commenced from divergent points of view, the ensuing dialogues frequently created new relationships and understandings between the engaged groups. This in turn has spawned new realities with respect to how the stakeholder organizations and institutions planned to conduct their respective environmental activities in the future. This reflects the perspectives of Giddens (1986) and Hall (1994) who suggest that the evolution and management of power relations governs the interactions between individuals, organizations, and agencies. This influences the structure of the institutions as well as the policy and programs they implement.

Such interactions reshaped the ways in which W-B and community stakeholders (governmental and non-governmental) led the destination on a path towards greater sustainability. The development of stakeholder connections between what seemed initially to be opposing power bases reflected a growing capacity of producer and non-producer institutions in Whistler, as well as a considerable level of commitment to engaging one another for individual and collective goals.

Appropriate Tension

While some proponents of strong W-B–ENGO relationship building believe that such collaborations encourage greater opportunities for improved “on-the-ground” environmental actions, others fear a loss of credibility and power if the ENGOs are perceived to have been co-opted by the corporation. These perspectives are at the heart of a healthy tension that must be managed and nurtured by the collaborating partners. For organizations like AWARE, the management challenge is to select the type of engagement that fosters actions in line with the community’s vision and environmental priorities, without its “environmental watchdog” voice being muted by corporate priorities. AWARE’s perceived independence and option to engage in more aggressive pressure tactics were invaluable tools and important precursors to meaningful forms of engagement with W-B.

For W-B, the management challenge was to engage with AWARE in ways that respected the organization’s independence yet nurtured relationships that will help it retain its “social license to operate”. Beyond utilizing AWARE to help identify and address environmental challenges related to the company’s operations, W-B required the ENGO’s independent and critical approval for its existing and proposed development activities. Consequently, it was as important to nurture and support the independence and vigilance of such “outsider” organizations as it was to directly collaborate with them. In this respect, W-B’s social license to operate was dependent on receiving permission from a credible organization that was perceived to have not been co-opted by the corporation. Notwithstanding the value of closer stakeholder relations between AWARE and W-B, the paradox is that there remained a need for a critical and independent voice in Whistler’s public arena. Consequently an important management challenge for both W-B and AWARE is not to try to resolve the paradox, but rather to manage it effectively.

This chapter presents a range of characteristics that epitomize the nature of corporate-civil society stakeholder relationships in a specific “Western style” tourism destination. Many of the characteristics identified reinforce motivations, engagement strategies and outcomes reported in the literature. The discussion suggests that over several years that a constructive synergy emerged between W-B and its primary ENGO stakeholders. However, this did not occur without recurring challenges. For instance, since the completion of the research for this chapter’s case study, W-B’s ownership has changed three times. As it shifted from being the flagship resort in a Canadian-owned Vancouver-based private sector company in 2003, to an internationally owned asset in a large venture capital company (Fortress) in 2008, to its most recent status as a publicly traded Canadian-owned and Whistler-operated company (Whistler Blackcomb) in 2010, its “social license to operate” has evolved. When acquired by the bottom-line focused Fortress organization, W-B’s legitimacy as partner in Whistler’s journey towards sustainability ebbed significantly. Much uncertainty existed about the share-price driven and shareholder orientation of Fortress and how that foucs would align with Whistler’s sustainability priorities. This concern largely evaporated when Fortress was “sold off” to the more locally oriented W-B company. Such shifts point to some interesting vulnerabilities associated with nurturing and retaining social license to operate.

In a corporate context, contextual conditions (e.g. magnitude and scope of the issue, personal and professional risk associated with decision making, changes in organizational leadership) can quickly alter the character of stakeholder engagement. This is the case especially if the level of engagement is built solely around personal considerations. More opportunity for sustained engagement exists if collaborative activities extend well beyond personal connections and issue-dependent arrangements to include more formalized process-oriented relationships.

Similarly, investigations in other jurisdictions where Intrawest operates suggest that the W-B approach to stakeholder engagement was not universally applied (Williams et al., 2007). Indeed, evidence from other geographic locations suggests that a more proactive approach to ENGO stakeholder involvement might have led to better long-term results for the corporation and the communities in which it operated (ibid.). However, more research is needed concerning what approaches to engagement generate the most productive results under varying circumstances.

In an era of growing corporate influence and power, it is probable that corporations such as Intrawest and now W-B will increasingly be compelled to not only conduct their businesses within existing formal regulatory environments established by government, but also operate within the informal social value systems of the destinations in which they locate. As a consequence, the expedience with which they are able to move forward with their own agendas will increasingly be linked to their ability to meet expected legal requirements as well as obtain and maintain their social license to operate.

Only limited research has been conducted to inform tourism corporations and ENGOs concerning those engagement strategies that serve the interests of their shareholders and stakeholders. Specific themes for future research follow.

Communication

Simply engaging stakeholders does not guarantee that successful outcomes will come from such relationships. Communication strategies that strengthen the ability of all parties to effectively transmit their own perspectives, receive the viewpoints of others, and understand how to process and collectively use such information are needed to support such engagements. Communication research should focus on creating effective means for the assessment, measurement, and reporting of stakeholder activities and how they vary in their situational appropriateness.

More research is also needed concerning the character of effective stakeholder dialogue. While considerable practitioner support exists concerning the importance of such discourse, little academic research has addressed methods of actively engaging stakeholders in effective dialogue.

Power

Understanding the role of power and its influence on corporate–community stakeholder relationships is needed. Many tourism destinations experience asymmetrical distributions of power that typically make real stakeholder engagement challenging if not impossible. In the case of Whistler, there was a seemingly more equitable sharing of specific types of power between W-B and its community stakeholders. More research is needed to determine how power and social behavior manifest themselves in varying stakeholder engagement situations.

Networking

In many “Western” tourism destinations, corporations are increasingly being viewed as entities embedded in a complex web of symbiotic relationships with other organizations and institutions. This perspective decentralizes the role of the corporation as the champion of change or action and creates the need for more community-led initiatives. More research is needed to explore how destination stakeholders should best organize their networks in order to achieve specific goals. While corporate- and community-based models of destination management exist, research concerning which networking strategies are most appropriate for engaging stakeholders in activities that lead to social license to operate for destination producer groups is needed.

Transferability

As with most case study research, this chapter’s findings are geographically, temporally, and institutionally specific. It is quite probable that its outcomes with respect to specific strategies would vary from place to place. Indeed, research conducted in other settings by the authors suggests that this may be the case. However, there are some underlying principles and perspectives presented which are worthwhile exploring in terms of their presence and significance in other settings. The model presented in the paper offers a lens from which to examine such relationships. Only case study research of this type conducted in a variety of settings will determine the transferability and utility of the engagement approaches uncovered in this chapter.

de Araujo, L. M. and Bramwell, B. (1999) ‘Stakeholder assessment and collaborative tourism planning: The case of Brazil’s Costa Dourada project’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 7(3/4), 356–78

Ashworth, G. J. and Dietvorst, A. G. J. (eds) (1995) Tourism and spatial transformations. Wallingford: CAB International

Banerjee, S. B. (1998) ‘Corporate environmentalism: Perspectives from organizational learning’. Management Learning, 29(2), 147–64

Banerjee, S. B. (2001) ‘Managerial perceptions of corporate environmentalism: Interpretations from industry and strategic implications for organization’. Journal of Management Studies, 38(4), 489–513

Barney, J. (1991) ‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120

Bendell, J. (2000) Terms for endearment: Business, NGOs and sustainable development. Sheffield: Greenleaf

Berry, M. A. and Rondinelli, D. A. (1998) ‘Proactive corporate environmental management: A new industrial revolution’. Academy of Management Executives, 12(2), 38–50

Burns, P. (1999) ‘Editor’s note: Tourism NGOs’. Tourism Recreation Research, 24(2), 3–6

Carroll, A. B. (1999) ‘Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct’. Business and Society, 38(3), 268–95

Clarkson, M. E. (1995) ‘A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance’. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117

Connor, T. and Atkinson, J. (1996) Sweating for Nike: A report on labour conditions in the sport shoe industry (Community Aid Briefing Paper No. 16). Seattle, DC: Nike

Cragg, W. (1996) ‘Shareholders, stakeholders and the modern corporation’. Policy Options, 17, pp. 15–20

Cunningham, N., Kagan, R. A. and Thornton, D. (2003) Shades of green: Business, regulation and environment. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

Delmas, M. and Terlaak, A. (2001) ‘A framework for analyzing environmental voluntary agreements’. California Management Review, 43(3), 44–63

Elkington, J. and Fennell, S. (1998) ‘Partners for sustainability’. Greener Management International, 24, 48–60

Evans, G. (2001) ‘Human rights, environmental justice, mining futures’. Retrieved 31 October 2011, from http://www.austlii.educ.au/au/other/HRLRes/2001/14

Flagestad, A. and Hope, C. A. (2001) ‘Strategic success in winter sports destinations: A sustainable value creation perspective’. Tourism Management, 22(5), 445–61

Getz, D. and Timur, S. (2005) ‘Stakeholder involvement in sustainable tourism’. In W. Theobald (ed.) Global tourism. New York: Elsevier, pp. 230–47

Gibson, R. and Peck, S. (2001) ‘Pushing the revolution: Leading companies are seeking new competitive advantage through eco-efficiency and broader sustainability initiatives’. Alternatives, 26(1), 20–29

Giddens, A. (1986) Central problems in social theory. London: Macmillan Press

Gill, A. and Williams, P. W. (2006) ‘Corporate responsibility and place: The case of Whistler, British Columbia’. In T. Clark, A. Gill and R. Hartmann (eds) Mountain resort planning and development in an era of globalization. New York: Cognizant Communication, pp. 26–40

Hall, C. M. (1994) Tourism and politics: Policy, power and place. New York: John Wiley and Sons

Harrison, J. S. and St. John, C. H. (1996) ‘Managing and partnering with external stakeholders’. Academy of Management Executive, 10(2), 46–60

Hart, S. L. (1995) ‘A natural-resource-based view of the firm’. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 986–1014

Hillman, A. J. and Keim, G. D. (2001) ‘Shareholder value, stakeholder management and social issues: What’s the bottom line?’. Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125–39

Intrawest (2003) ‘Play: Intrawest Annual Report 2001’. Retrieved 31 October 2011, from http://highered.mcgraw-hill.com/sites/dl/free/0070891737/75681/Intrawest2001AR1.pdf

Jamal, T. B. (1999) ‘The social responsibilities of environmental groups in contested destinations’. Tourism Recreation Research, 24(2), 7–17

Jamal, T. B. and Getz, D. (1995) ‘Collaboration theory and community tourism planning’. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204

KPMG Management Consulting (1995) Developing business opportunities through partnering: A handbook for Canada’s tourism industry. Ottawa: Industry Canada

Lama, W. B. (2000) ‘Community-based tourism for conservation and women’s development’. In P. Godde, M. Price and F. M. Zimmermann (eds) Tourism and development in mountain regions. New York: CABI International, pp. 221–38

Lyon, T. (2003) ‘“Green” firms bearing gifts’. Regulation, 26(3), 36–40

Marcoux, J. (2004) ‘Community stakeholder influence on corporate environmental strategy at Whistler, BC’ (Research Paper No. 362). Unpublished Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, British Columbia

Moore, J. (2001) ‘Frankenfood or doubly green revolution: Europe vs America on the GMO debate’. In A. H. Teich, S. D. Nelson and S. J. Lita (eds) AAAs science and technology yearbook. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, pp. 173–80

Moore, S., Williams, P. W. and Gill, A. (2006) ‘Finding a pad in paradise: Amenity migration’s effects on Whistler, British Columbia’. In L. A. G. Moss (ed.) The amenity migrants: Seeking and sustaining mountains and their cultures. Wallingford: CABI International, pp. 135–47

Murphy, D. E. and Bendell, J. (1997) In the company of partners: Business, environmental groups and sustainable development post-Rio. Bristol: Policy Press

Murphy, P. E. and Murphy, A. E. (2004) Strategic management for tourism communities: Bridging the gap. Clevedon: Channel View Publications

Nattrass, B. and Altamore, M. (2003) Dancing With the Tiger: Learning Sustainability by Natural Step. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers

Neale, A. (1997) ‘Organisational learning in contested environments: Lessons from Brent Spar’. Business Strategy and the Environment, 6(2), 93–103

Norcliffe, G. (2001) ‘Canada in the world’. Canadian Geographer, 45(1), 14–30

NSAA (2000) Sustainable slopes: The environmental charter for ski areas. Lakewood, CO: National Ski Areas Association

Parker, C. (2002) The open corporation: Effective self-regulation and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Porter, M. E. and van der Linde, C. (1995) ‘Green and competitive: Ending the stalemate’. Harvard Business Review, 73(5), 120–34

Prahalad, C. K. and Hamel, G. (1990) ‘The core competence of the corporation’. Harvard Business Review, 68(3), 79–91

RMOW (2002) Whistler 2002, Vol. 1: Charting a course for the future. Whistler, BC: Resort Municipality of Whistler

RMOW (2004) Whistler 2020: Moving toward a sustainable future. Whistler, BC: Resort Municipality of Whistler

Robson, J. and Robson, I. (1996) ‘From shareholders to stakeholders: Critical issues for tourism marketers’. Tourism Management, 17(7), 533–40

Rondinelli, D. A. and Berry, M. A. (2000) ‘Environmental citizenship in multinational corporations: Social responsibility and sustainable development’. European Management Journal, 18(1), 70–84

Rothman, H. K. (1998) Devil’s bargains, tourism in the twentieth-century American West. Laurence, KS: University Press of Kansas

Scholzman, K. and Tierney, J. (1986) Organized interests and American democracy. New York: Harper and Row

Svendsen, A. (1998) The stakeholder strategy: Profiting from collaborative business relationships. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler

Svendsen, A., Boutilier, R., Abbott, R. and Wheeler, D. (2002) Measuring the business value of stakeholder relationships. Burnaby, BC: Centre for Innovation in Management, Simon Fraser University

Todd, S. E. and Williams, P. W. (1996) ‘From white to green: A proposed environmental management system framework for ski areas’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 4(3), 147–73

van Yoder, S. (2001) ‘Beware of the coming corporate backlash’. Industry Week, 250(5), 38–42

Wernerfelt, B. (1984) ‘A resource-based view of the firm’. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–80

Williams, P. W. and Gill, A. (2004) ‘Addressing carrying capacity issues in tourism destinations through growth management’. In W. Theobald (ed.) Global tourism. London: Elsevier, pp. 194–212

Williams, P. W., Gill, A. and Ponsford, I. (2007) ‘Corporate social responsibility at tourism destinations: Toward a “social licence to operate”’. Tourism Review International: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 11(2), 133–44

Williams, P. W., Penrose, R. and Hawkes, S. (1998) ‘Shared decision-making in tourism land use planning’. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(4), 860–89

Wright, M. S. (1998) Factors motivating proactive health and safety management (Research Report No. 179/1998). London: Health and Safety Executive

Xu, N. (2004) ‘The changing nature of corporate-environmental non-governmental organization relationships: A Whistler case study’ (Research Paper No. 358). Unpublished Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, British Columbia