The case of the tourism policy forum

You can’t manage knowledge, but you can create an environment where knowledge flows easily. For me, it’s less important to capture all of the knowledge we have and it’s more important to be connected to the people who have the knowledge.

(Parcell, 2005, p. 727).

As one of the largest global industries and employers, tourism has a significant role in the economies of developed and developing countries alike. It is increasingly an important development strategy for addressing poverty reduction, economic growth, biodiversity, and conservation, and, specifically, the United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (UN, 2000).1 According to the World Bank’s “World Development Indicators” 2002 report, more than 70 percent of the world’s poorest countries rely on tourism as a key economic growth engine (World Bank, 2002). The WTTC reported a 154 percent growth in tourism absolute earnings for the least developed countries (LDCs) during the period 1990 to 2000, and a 74.8 percent growth in international tourist arrivals for those countries during the same period (UNWTO, 2002).

Acknowledging this reality, development assistance projects are increasingly using tourism as a means of fostering sustainable development. However, there is a scarcity of information concerning appropriate engagement levels for development assistance in efforts to enhance tourism revenues for developing economies. For many years tourism and its contribution to the global economy remained ill-defined for the general population, and often not well understood even by those in the industry, including policymakers. In a survey conducted by the World Travel and Tourism Council in 1991, 150 policymakers in 14 countries were asked to rate industries according to their perceived importance to the world economy. Among 13 world industries, tourism was rated near the bottom, as 11th in importance. When the study was repeated the following year, tourism fared somewhat better, rising to number eight in perceived economic importance (WTTC, 1992). There are also difficulties in balancing the public sector role while maintaining a competitive private sector environment, which determines, in part, whether or not benefits from tourism will actually reach the poor host communities who are at the front line of receiving tourists (Milne and Ateljevic, 2001).

Development assistance for tourism has but a short history of 30 to 40 years. In most countries, tourism continues to be an ongoing social, economic and environmental challenge. With nearly 50 bilateral and multilateral donor agencies involved in development assistance for tourism, the logistical challenges of communication and cooperation are significant, due to language differences and differing investment strategies and approaches to tourism development. At the same time, improved information communication technologies (ICT) have emerged in the past two decades, particularly the Internet and the world wide web (WWW), to create greater efficiency in the global sharing of knowledge and knowledge management (KM). However, harnessing ICT and global information inputs requires a systematic KM approach whereby information and knowledge can be equitably communicated and shared, leading to the generation and implementation of policies and strategies for optimizing tourism growth in the developing countries of the world.

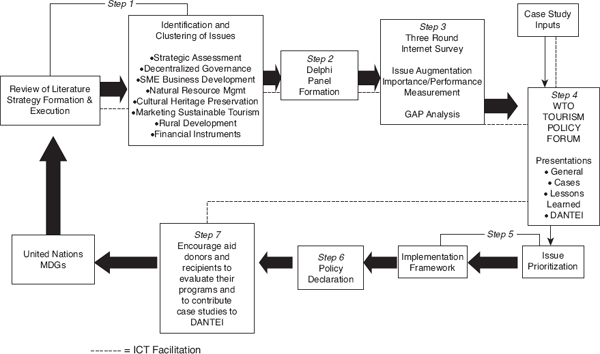

This study presents the case of the 2004 UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) Tourism Policy Forum, held at George Washington University in Washington, DC, where ICT facilitated the consensus building approach that was used for constructing a knowledge management network among development assistance donors and recipients, for the purpose of improving tourism’s contribution to sustainable development goals. The consensus building approach is presented in Figure 14.1.

The consensus building approach was based on assumptions that there is a need for:

The general assumption of the consensus building approach developed for the Tourism Policy Forum is that sustainable forms of tourism development can best be achieved through the KM process whereby research and intellectual property can help tourism enterprises and destinations achieve new capabilities that assure their long term viability and success. The construct behind KM, which was introduced into business literature in the 1990s, is that individuals should be encouraged to share ideas and knowledge to create value-added products and services (Ruhanen and Cooper, 2004). A KM framework encourages organizations to capitalize on their intellectual assets (e.g. employee skills, or an organization’s dynamic capabilities) as opposed to traditional commodity assets and physical goods (e.g. oil, gas, minerals, factories). Nielson (2005, p. 5) suggests that the shift towards KM frameworks occurred in the twentieth century when “we made a transition from a matter-based economy to a knowledge-based economy, where most of a firm’s value is embedded in knowledge assets.” In defining new applications of knowledge management, Spender (2005, p. 102) contends that

KM is about identifying as wide a range of knowledge assets as possible—be they forms of knowledge, or knowing, or proficient practice at the individual, group, organizational, cluster, industry, region or national level—and bringing them into our theorizing about maximizing efficiency, profit, or market power.

A Consensus Building Approach for Optimizing Tourism’s Potential as a Sustainable Development Strategy in Developing Countries: The Case of the WTO Tourism Policy Forum

Figure 14.1 Tourism policy forum consensus building approach

Levy (2005, p. 65) describes such KM processes as a “convergence of mental technologies along with network technologies designed to leverage the bench strength of an organization’s human capital.” The most important development in information communication (IC) network technologies facilitating KM has obviously been the Internet and the world wide web. In most instances of KM approaches, organizations are involved with both explicit and tacit knowledge flows. Nielsen (2005) describes explicit knowledge as knowledge that can be transmitted through symbols and language, whereas tacit knowledge is knowledge that is intuitive.

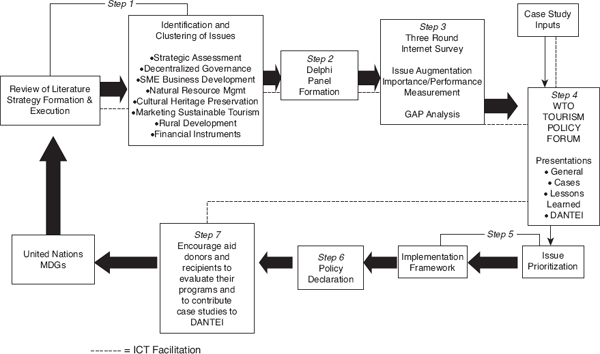

Ruhanen and Cooper (2004) argue that the tourism sector has largely not benefited from KM approaches due to the fact that the sector is comprised for the most part of small to medium-sized enterprises who do not have the time or interest in research. They also maintain that tourism organizations have not embraced KM because these organizations have been largely service- and product-based. They propose a “knowledge value chain” to assist the sector in capitalizing its intellectual assets. This value chain includes four steps:

Frechtling (2004) argues that two more steps are needed:

5. Stakeholder appreciation of knowledge to achieve objectives.

6. Feedback on success in achieving objectives.

Frechtling’s research concludes that there is little or no research on knowledge transfer between researchers and “salient stakeholder groups” (private, public, and nonprofit sector tourism organizations). His study concluded that there was little transfer of knowledge between tourism research “generators” and tourism practitioners.

As development agencies are increasingly engaged in sustainable forms of tourism development, due to increased demand from developing countries for tourism-related lending and advice, the need for information, knowledge gathering and sharing is particularly critical. At the same time, literature continues to question the effectiveness of donor aid projects. In examining “History, independence and aid in Lesotho” the Near East Foundation summarized, “The bones of failed aid projects litter Lesotho, just as they do most of sub-Saharan Africa” (Near East Foundation, 1998, p. 14). A regional sub-Saharan scholar, Stephen Gill, suggests that foreign experts and local bureaucracies are the problem. He states that, although these groups may have good plans and intentions, “the crucial element of accountability and feed-back from communities affected by such projects is often lacking” (Gill, 1993, p. 77). He argues that what is needed is a “better balance of aid, local participation, and control...which actually empowers people, institutions or communities to improve their standard of living without creating long-term dependency on donors” (ibid.). In Ills of Aid, Reusse (2002) also argues that aid agencies are not accountable and essentially detached from taxpayer scrutiny from the country providing the aid.

Thus, the design of the consensus building approach of the Tourism Policy Forum was to create an environment whereby knowledge can easily flow, whereby donor aid accountability systems and reviews can be integrated, and whereby a system of connections among people who have and need knowledge can be accessed. The objective of such a consensus building approach, incorporating a knowledge management framework, was to assist developing countries in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) set forth by the United Nations, and in particular, goals one, seven and eight: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; ensure environmental sustainability; and develop a global partnership for development.

Table 14.1 Knowledge management framework and the consensus building approach of the Tourism Policy Forum

The seven-step consensus building approach for the Tourism Policy Forum (see Table 14.1) incorporated the stages of the “knowledge value chain” suggested by Rhuhanan and Cooper (2004) with the additional two suggested by Frechtling (2004). The KM framework was created to facilitate the transformation of knowledge into capabilities and actionable plans.

The consensus building approach utilized established qualitative research methodologies in the seven-step process including content analysis (for the initial clustering of issues), Delphi panel (for prioritizing issues in terms of importance/performance measurement for GAP analysis), and nominal group process (NGP) techniques (for further issue distillation and prioritization, formulation of recommendations, and the development of an implementation framework).

Central to the focus of the Tourism Policy Forum is that there are shortfalls (gaps) across a spectrum of issues, in terms of relative importance, as well as the ability (i.e. performance) of the aid donor or recipient organization to meet the challenge of addressing a particular issue. The consensus building approach used for the Tourism Policy Forum incorporated seven research steps.

Step 1: Review of literature and identification of themes

A review of the current discussions in literature and an examination of development agencies’ funding of tourism projects in LDCs was first conducted to identify the primary themes or strategic directions concerned with tourism development. The eight themes that emerged from this review and examination included:

Step 2: Expert panel and the Delphi method

The consensus model approach then utilized a research process, the Delphi method, which was first developed by the Rand Corporation in 1963 to predict, through a consensus of experts, what places in the United States might become atomic bomb targets of the Soviets (Dalkey and Helmer, 1963; Helmer, 1966). The Delphi process was later expanded for use in other disciplines, including medical and social science research. The Delphi is a qualitative research method, which involves “structuring a group communication process so that the process is effective in allowing a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem” (Linstone and Turoff, 1975, p. 3). It involves a panel of experts, not a random sample of respondents (population survey). Delphi studies involve iterative rounds, usually incorporating a semantic differential scale, with the group opinion fed back to the panelists in each subsequent round in the form of the range and distribution of the responses (quartile rankings, means, modes, etc.). Panelists are asked to re-evaluate their previous response in iterative rounds, considering the group opinion, and then again respond to the same problem statements or issues as well as new ones suggested by panelists (Moutinho and Witt, 1995). One of the long considered disadvantages of the Delphi is panel member attrition in the iterative survey rounds advance. In recent years, ICT via the Internet has greatly compensated for this drawback and the Delphi method is now used in a diverse range of fields and applications. An Internet search revealed over 745,000 links. The Internet has greatly facilitated a system of instant communication globally, and at a fraction of the cost when compared to older forms of ICT, such as postal mail, telephone, fax, etc.

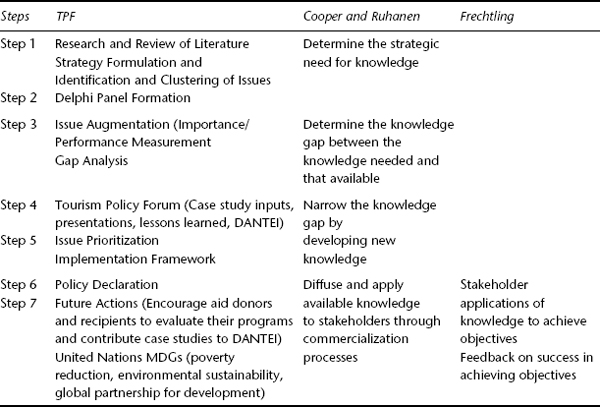

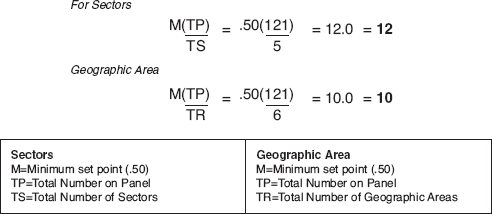

For management purposes, the panel for this phase of the consensus building approach was set not to exceed 125 participants. In constituting the panel, geographic area and sector of expertise were considered, with members selected to reflect representative units, as shown in Table 14.2.

In the formation of the panel, the objective was not to achieve unit parity, but, in order to assure adequate representation at the geographic and sector level, it was considered essential to establish minimum population thresholds by using the acceptance minima shown in Figure 14.2.

In structuring the panel, thresholds for representation in the study, while imperfect and artificial, were designed to limit any region or sector from dominating the results of the survey. Thresholds were set to ensure that no category represented by the survey population would make up more than twice the average, nor less than half the average as indicated in the above equation. The threshold equation was developed for an earlier study that incorporated the Delphi process for the World Tourism Organization’s Tedqual project (UNWTO, 1997).

| Expertise by region | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| East Asia and the Pacific | 13 | 10.7 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 13 | 10.7 |

| Global | 33 | 27.2 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 21 | 17.4 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 10 | 8.3 |

| South Asia | 10 | 8.3 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 21 | 17.4 |

| Total | 121 | 100 |

| Expertise by sector | ||

| Development Agency | 25 | 20.7 |

| Education | 33 | 27.3 |

| Government | 13 | 10.7 |

| NGO | 15 | 12.4 |

| Private Sector | 35 | 28.9 |

| Total | 121 | 100 |

Step 3: Gap analysis and importance/performance measurement

The design plan for this study included a three-round online consensus building survey of experts utilizing an importance/performance measurement tool to identify issues and issue shortfalls (gaps). Importance/performance analysis was introduced by Martilla and James (1977) as a method for understanding customer satisfaction as a function of both expectations related to salient attributes (“importance”) and judgments about their performance (“performance”) (Magal and Levenburg, 2005). Importance/performance literature falls into two areas: research that deals with the identification of performance gaps (generally measured as performance minus importance); and research that involves the plotting of mean ratings on importance and performance in a two-dimensional grid (termed the “Action Grid” by Crompton and Duray, 1985) to produce a four-quadrant matrix that identifies areas needing improvement, as well as areas of effective performance (Graf et al., 1992; Skok et al., 2001).

Figure 14.2 Panel acceptance minima

Source: UNWTO, 1997

The consensus building approach used in the Tourism Policy Forum produced qualitative data, which could then serve as an initial step in identifying issues. Being able to conduct the multiple-round survey online was considered an important feature of this study. The Internet provided an efficient means whereby such a study could involve the participation of individuals throughout the world, be completed within a relatively short period, then tabulate and report the results of each survey round back to the panelists through a website.

In the first round of the survey, panelists were presented with a set of issues organized according to the Tourism Policy Forum’s eight strategic themes. Listed below each theme were three issues that emerged from the literature review as the important “need areas” for sustainable development through tourism in developing countries. The panelists were requested to rate the issues according to the importance (of the need area) in fulfilling the promise of tourism’s potential as a sustainable development strategy in developing countries. Next, they were asked to rate the issue statement based on the performance capacity of aid donors and developing country recipients to meet the challenge of addressing the identified issues (1 being the lowest performance and 10 the highest performance).

The panelists were also given the opportunity to add any issue or “need area” they would like to bring to the survey panel’s attention for judgment in the next round. If panelists did not feel qualified to judge a particular issue, they were instructed simply to select “no opinion.” 121 individuals agreed to serve on the Tourism Policy Forum panel. While Delphi surveys typically encounter the problem of participant drop-off in subsequent panel rounds, the opposite occurred in this online application of the Delphi. It appeared that the immediate reporting of each round’s results to all participants by email (which directed participants to the next survey round on a website) stimulated interest, resulting in greater participation rates for each survey round. Increased participation with each round also suggests that participants found the online survey efficient and easy to use. In the first survey round, 41 percent of the Delphi panel participants responded.

In the second round, the results were reported back to the panelists. Means were calculated for each issue in terms of the issue’s importance, as well as aid donor or aid recipient performance in meeting that issue’s challenge. The issues were rated according to the gap, the greatest difference in means (i.e. where importance would be considered highest and performance considered poorest). Panelists’ “write-in” issues from the first round were included for consideration in the second survey round. Annex 1 contains a listing of the priority issues identified for each strategic theme. In the second survey round, 50 percent of the Delphi panel participants responded.

In the third round, the three top-rated issues in each theme area, again rated according to the greatest gap, were reported back to the panelists. In this final round, the panelists were asked to make recommendations or suggest solutions for closing the gap for each issue. Participants in the Tourism Policy Forum were also invited to submit recommendations addressing the identified issues. In the third survey round, 94 percent of the Delphi panel participants responded.

Thus, the consensus building approach for the Tourism Policy Forum involved a combination of qualitative assessment techniques including the Delphi panel and iterative rounds of polling, the importance/performance analysis, and the gap measurement methodological stream of the importance/performance analysis.

The 24 issues that panelists were asked to rate in the first round of the survey grew to 67 issues to be rated in the second round. In the third and final round of the survey, the top 25 issues that emerged from panelists’ polling were presented for consideration and recommended solutions. From this round, 15 to 20 recommendations per issue were identified and vetted by a committee, who condensed duplicated statements. In the end, there were 10 to 12 recommendations per theme area that would be available for live working group discussion and debate when the Tourism Policy Forum convened in Washington, DC, in October 2004. Recommendations generated from the survey became a starting point for the more detailed assessment process that would take place at the Tourism Policy Forum.

Table 14.3 Tourism policy forum objectives

| Tourism policy forum objectives |

|

Step 4: Tourism Policy Forum

The purpose of the 2004 Tourism Policy Forum was to convene educators, knowledge management experts and other informed professionals, representative government policymakers, and business leaders to focus on the critical policy issues facing global tourism and to offer recommendations for the future. The objectives of the Forum are listed in Table 14.3.

The Forum attracted 200 participants and more than 200 observers from 52 countries, representing tourism ministries, development assistance agencies, UNWTO and other UN organizations, education institutions, NGOs, and private businesses. The three-day Forum program included keynote addresses, panel discussions, the presentation of case studies, and special workgroup sessions. Representatives from the Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank Group, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and UNWTO gave keynote presentations. The Forum also included panel discussions by ministers of tourism from South Africa, Jordan, Nicaragua, Honduras, Lesotho and Andorra, as well as panel discussions of bilateral donors (SNV, GTZ, USAID and CIDA, among others). Case study presentations organized for each of the eight strategic themes produced a set of challenges and lessons learned that later served to stimulate thinking in the concurrent workgroup sessions. During those sessions, participants were asked to prioritize the issues and recommendations, and develop an action plan for implementing the recommendations deemed most important.

Step 5: Issue prioritization, recommendations and implementation framework

The online survey and issue identification process in steps 2 and 3 provided the Tourism Policy Forum participants a platform for discussion within the eight established thematic areas. Specialized working group sessions were conducted during the Forum for formulating concrete recommendations and implementation steps. The first half of each session was dedicated to case study presentations made by five or six experts in the session theme area. The intent of these presentations was to provide ideas and lessons learned for the working group discussions that took place during the second half of the session, with participants divided into three groups corresponding to the three priority issues generated through the consensus building survey. Each working group was presented with 10 to 12 recommendations related to a priority issue generated through the survey, and asked to consider them as written, amend them, adapt them, or add new ones. Each group then voted to determine the two or three most important recommendations, and, finally, the group was asked to develop an implementation framework that covered what mechanisms were to be used, how they would be accomplished and by whom. The group’s findings were captured on flip charts and presented to all Forum participants during morning and afternoon plenary sessions.

As an illustration of results generated from this approach, one theme area is presented: decentralized governance and capacity building. Under this theme, the following three issues were identified through the survey process:

For one such issue, “Adequate budget allocations from central government,” recommendations generated through the survey are listed in Table 14.4 and those added by the working groups at the Tourism Policy Forum are listed in Table 14.5.

Table 14.4 Adequate budget allocations from central government 1

| Adequate budget allocations from central government Recommendations Generated Through Survey Process (Note: Highest priority recommendations listed in Bold Face) | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Link budgets to clear strategies, plans and envisaged outcomes. Benchmarking, evaluation and monitoring should be integral. Central government should be provided with tangible results of the impacts of their investment in tourism. This will help them justify their budget allocations to their constituencies and also provide them with a frame of reference for future budget allocations. |

| 2 | Build strong economic arguments for government support and government investment in tourism. Tourism satellite accounts, employment data and regional development theory are all important components of this, but also political support requires strong advocacy groups to undertake the lobbying. |

| 3 | Prioritize budgets and focus on areas/aspects of tourism with greatest potential. |

| 4 | Encourage collaborative relationships by tourism ministries with other departments (culture, sport, natural resources, agriculture, education) |

| 5 | Create new ways for self-sufficiency, such as in-kind & in-cash awards. |

| 6 | Make allocations transparent to the public from the bidding process to evaluations. |

| 7 | Publish budget information on relevant websites. |

| 8 | Implement appropriate cost recovery mechanisms so as to provide the necessary capital to expand, operate, and maintain infrastructure. Promote private sector participation in infrastructure–PPI. |

| 9 | Explore partnering with tourism enterprises to extend private sewage and waste and treatment facilities, such as the facilities at larger hotels, to local communities. |

| 10 | Increase the awareness of key indicators of the importance of tourism at public and political levels. |

| 11 | Measure the local economic impact of tourism and use results as a tool for strategic planning, budgeting and resource allocations. |

Table 14.5 Adequate budget allocations from central government 2

| Adequate budget allocations from central government Recommendations Generated Through Survey Process (Note: Highest priority recommendations listed in Bold Face) | |

|---|---|

| 12 | Use Government budgets to support local communities, develop structures, build capacity, facilitate partnerships/agreements between stakeholders (PPI’s). |

| 13 | Develop budgets that have finance mechanisms and money (various sources). |

| 14 | Build strong economic arguments for government support and government investment in tourism. Tourism satellite accounts, employment data and regional development theory are all important components of this, but also political support requires strong advocacy groups to undertake the lobbying. |

Working groups then developed an implementation framework for each of the prioritized recommendations, as illustrated in Table 14.6.

The complete set of issues, recommendations, and implementation framework results are available in the Tourism Policy Forum section of the DANTEI website (http://www.dantei.org).

Step 6: Policy declaration

The culminating activity of the Forum was the “Washington Declaration on Tourism as a Sustainable Development Strategy.” This was based upon reports submitted by reporters at each session to the Declaration Committee Chair, Professor Pauline Sheldon from the University of Hawaii at Manoa. During the Forum, the resolution was drafted to reflect the consensus of the participants on conclusions and recommendations focused on the role of tourism in sustainable development. At the final session, the draft declaration was circulated to the participants and then discussed. Based upon the points raised, the Declaration was revised in final form. It was forwarded to the Secretary General of the UNWTO for consideration and included in the final proceedings of the Tourism Policy Forum, published by UNWTO in early 2005.

Set forth in this document were the following agreed resolutions:

Table 14.6 Adequate budget allocations from central government 3

| Build strong economic arguments for government support and government investment in tourism. Tourism satellite accounts, employment data and regional development theory are all important components of this, but also political support requires strong advocacy groups to undertake the lobbying. | |

|---|---|

| What? |

• Measurement of local economic impact of tourism and use results as a tool for strategic planning, budgeting and resource allocations). • Private sector support to make the argument. • Independent tourism research unit with sub regional levels (national/local). |

| How? |

• Links to various initiatives including role of advocacy, universities, private sector, civil society. • Must be self sustaining. • Dissemination between ministries and universities (2 way). |

| Who? | • Local universities with connections to international support /expertise. |

Step 7: Encourage aid donors and recipients to evaluate programs and contribute to DANTEI

Through the consensus building approach it was evident that all of the donor agencies shared the common ground of currently being unable to accurately define their engagement with the tourism sector in terms of financial commitment or knowledge of tourism projects’ past successes and failures. There was agreement that an internal auditing of tourism projects by individual agencies would be a useful next step (considering this was being done by the World Bank and USAID already). While some of these issues are internal, indicators of success or failure and best practice could be benchmarked internationally for everyone’s benefit.

An analysis of the case studies presented at the Forum showed a total of 60 different and specific challenges and 74 lessons learned in the eight theme areas. The special workgroup sessions produced more than 20 implementation steps (frameworks) for mitigating the issues where there was the greatest gap in the importance and performance index measurement. The consensus building approach brought various stakeholder groups together on a common global stage, all facilitated by advances in ICT, and all committed to working towards a better common future.

One of the specific outcomes of the Tourism Policy Forum process was the establishment of the DANTEI (Development Assistance Network for Tourism Enterprise and Investment) website. At the Forum, UNWTO and George Washington University (GWU), sponsors of the Tourism Policy Forum, demonstrated a web-based platform (http://www.dantei.org), developed to share information and knowledge about best practices, tools, and guidelines for tourism directed toward sustainable development outcomes.

The website was developed to help potential development assistance recipients (particularly government and civil society) access funding resources, and was also used to support the Tourism Policy Forum by showcasing the presentations and case studies. DANTEI could conceivably expand to provide a platform on which development agencies could share information, and a portal through which they could access capacity building training programs or useful tools and post best practices/lessons learned from project cases.

Accessible information about tourism and sustainable development is currently scattered over 150 websites, development assistance agency databases, and hundreds of books and publications. There is no neutral platform to filter, search for, or add to case studies, best practices, and information on donor-funded tourism projects, their outcomes, benefits, or costs. Existing sites tend to focus on the promotion of specific agendas, for example linking tourism to objectives such as biodiversity conservation, small business development, cultural heritage preservation.

The consensus building approach underpinning the Tourism Policy Forum facilitated the building of knowledge networks – government, private sector, civil society, etc. – to collaborate, not compete, and to leverage strengths and insights. The KM approach incorporated the latest ICT technologies (the Internet, websites, email, list servers, etc.) together with older forms of ICT (conferences, presentations, workgroups, and nominal group process techniques) to bring together disparate groups and interests, in order to find solutions and illuminate common issues. The approach utilized the Internet and recent developments in ICT to coalesce global thinking on the most salient issues and provided a live forum (UNWTO Tourism Policy Forum) to:

The process focused on the future of tourism as a significant contributor to the fulfilment of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). One outcome of this integrated approach is a searchable interactive database driven website, Development Assistance Network for Tourism Enhancement and Investment (DANTEI), that addresses the tourism-relevant information needs of government, NGO, and university aid recipients as well as researchers, investors, and bilateral or multilateral agencies engaged in the development assistance process.

While much success is deemed to have come about from the consensus building approach, forums in the future must address some of the problems that integrative ICT alone cannot solve. For example, problems still remain as to how to identify the right “experts” to be on the issue identification Delphi panel, how to keep even a higher percentage of “expert” panellists motivated, engaged and responding in all polling rounds, and how to apply the results from such a collaborative research endeavor.

For the most part, though, a KM framework facilitated by ICT has enabled developing countries and donor assistance organizations to take a better look at how tourism can be an effective strategy for sustainable development that will contribute to the realization of MDGs. The consensus building approach presented in this chapter is a step in that direction.

Tourism Policy Forum themes and issues identified through the survey

Decentralized governance and capacity building

Issues

1. Local capacity to plan, monitor and regulate tourism development.

2. Adequate budget allocations from central government.

3. Communication and collaboration between central and local government planning and budgeting cycles.

Rural development

Issues

4. Realistic assessments of opportunities undertaken.

5. Local communities included in rural tourism planning decisions.

6. Linkages with local productive sectors (e.g. agriculture, co-ops, artisans, chambers of commerce) developed.

SME (small and medium-sized enterprises) development and competitiveness

Issues

7. Cooperation and support mechanisms among SMEs (e.g. business councils, shared resources, collective marketing strategies).

8. Entrepreneurship and investment mentoring.

9. Development of diagnostic tools, such as value chain analysis, for defining limiting factors (e.g. quality standards, access to markets and access to finance).

Natural resource and protected area management

Issues

10. Better coordination between agencies responsible for natural resources management and tourism development.

11. Community awareness of the value of natural resources to long-term quality of living.

12. Flexibility in conservation financing and management including participation of private sector, NGOs and communities.

13. Policy incentives for private landowners to contribute to natural resource protection (e.g. conservation easements, conservancies, transfer development rights).

Cultural heritage preservation

Issues

14. Cultural authenticity needs to be viewed as a competitive advantage.

15. Stronger linkages between the private sector and cultural heritage preservation.

16. Creative funding of cultural heritage preservation (e.g, certification programs before accessing public money).

Foreign direct investment and enabling environments

Issues

17. Sharing of profits back to the community or region of production.

18. Strong sustainable tourism policies to guide FDI.

19. Policy reforms more effectively addressed to support tourism development.

Strategic assessment, planning and implementation

Issues

20. Effective public, private and civil society partnerships to enhance the effectiveness of tourism planning and implementation.

21. Available impact research data for decision-making, e.g. environmental impact assessment data, cultural impact assessment data, economic indicators and trends.

22. Strategic planning linked to realistic implementation expectations and actions.

Market access and export development

Issues

23. Provision of market research, realistic targets, and distribution channels for tourism products and services.

24. Technical capacity training for indigenous access to markets.

25. Regional collaboration to create greater marketing clout.

1 On September 8, 2000 the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted a resolution that set forth the UN’s MDGs. In essence these are eight goals that deal with poverty reduction, universal primary education, gender equality, infant mortality reduction, maternal health, disease prevention (particularly HIV), environmental sustainability, and global partnerships for development.

Crompton, J. L. and Duray, N. A. (1985) ‘An investigation of the relative efficacy of four alternative approaches to importance performance analysis’. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 13(4), 69–80

Dalkey, N. and Helmer, O. (1963) ‘An experimental application of the Delphi Method for the use of experts’. Management Science, 9(3), 529–53

Frechtling, D. C. (2004) ‘Assessment of tourism/hospitality journal’s role in knowledge transfer: An exploratory study’. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 100–107

Gill, S. J. (1993) A short history of Lesotho from the Late Stone Age until the 1993 elections. Morija, Lesotho: Morija Museum and Archives

Graf, L. A., Hemmasi, M. and Nielsen, W. (1992) ‘Importance-satisfaction analysis: A diagnostic tool for organizational change’. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 13(6), 8–12

Helmer, O. (1966) Social technology. New York: Basic Books

Levy, J. (2005) ‘The fourth revolution’. T+D, 59(6), 64–5

Linstone, H. A. and Turoff, M. (1975) The Delphi Method: Techniques and applications. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company

Magal, S. R. and Levenburg, N. M. (2005) ‘Using importance-performance analysis to evaluate e-business strategies among small businesses’. Proceedings of the 38th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://csdl.computer.org/comp/proceedings/hicss/2005/2268/07/22680176a.pdf

Martilla, J. A. and James, J. C. (1977) ‘Importance-performance analysis’. Journal of Marketing, 41(1), 77–9

Milne, S. and Ateljevic, I. (2001) ‘Tourism, economic development and the global-local nexus: Theory embracing complexity’. Tourism Geographies, 3(4), 369–93

Moutinho, L. and Witt, S. F. (1995) ‘Forecasting the tourism environment using a consensus approach’. Journal of Travel Research, 33(4), 46–50.

Near East Foundation (1998) ‘History, independence and aid in Lesotho: Littered with the bones of failed projects’. Near East Foundation, 1 January. Retrieved 3 November 2011, from http://neareast.org/main/news/article_pr.aspx?id=92

Nielsen, B. B. (2005) ‘Strategic knowledge management research: Tracing the co-evolution of strategic management and knowledge management perspectives’. Competitiveness Review, 15(1), 1–13

Parcell, G. (2005) ‘“Learning to fly” in a world of information overload’. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83(10), 727–9

Reusse, E. (2002) The ills of aid: An analysis of Third World development policies. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press

Ruhanen, L. and Cooper, C. (2004) ‘Applying a knowledge management framework to tourism research’. Tourism Recreation Research, 29(1), 83–8

Skok, W., Kophamel, A. and Richardson, I. (2001) ‘Diagnosing information systems success: Importance-performance maps in the health club industry’. Information and Management, 38(7), 409–19

Spender, J. D. (2005) ‘Review article: An essay of the state of knowledge management’. Prometheus, 23(1), 101–16

UN (2000) 55/2. United Nations Millennium Declaration. UN, 8 September. Retrieved 6 May 2005, from http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm

UNWTO (1997) An introduction to TEDQUAL: A methodology for quality in tourism education and training Madrid: UN World Tourism Organization

UNWTO (2002) Tourism and poverty alleviation. Madrid: UN World Tourism Organization

World Bank (2002) World Development Indicators 2002. Washington, DC: World Bank

WTTC (1992) The travel and tourism industry perceptions of economic contribution. London: World Travel and Tourism Council