Preliminary Findings from Comparative International Studies

Work in personal services such as hospitality is widely described as ‘low skills’ in both the academic literature (Shaw and Williams, 1994; Westwood, 2002; Wood, 1997) and the popular press. This stereotype is challenged in the context of hospitality in the work of a number of writers (Baum, 1996, 2002; Burns, 1997; Nickson et al., 2003) on the basis that this represents a Western-centric and product-focused perception of work and skills. The study reported in this paper seeks to contribute empirically to this debate by reporting preliminary findings from a trans-cultural, international comparison of work, training and skills application in one area of hospitality operations — that of the hotel front office.

The role of skills and skills development through training in the contemporary economy is a matter of considerable academic and political debate. There appears to be an inexorable move towards a redefinition of the economy of many countries in terms of poorly defined skill thresholds so that comparative statements about countries as high- or low-skill economies are paraded without seeming critical analysis of what such assertions actually mean. Public policy in many countries focuses on the development of what are seen as a high-skill employment and business environment (Brown et al., 2001). At the same time, most developed or high-skill economies also depend to a significant extent on an alternative economy based on what are loosely and pejoratively described as ‘low-skill’ jobs. Little critical analysis has been undertaken with respect to what such descriptors actually mean. ‘Low skills’ can be seen in terms of the actual technical requirements of the job — this is the most common interpretation — or as an indicator of the value that society places on work in the area in question. The two interpretations may have some overlap but are not necessarily synonymous.

This chapter reports preliminary findings from an empirical exploration of the extent to which our understanding of hospitality skills is socially and culturally constructed. Specifically, the research addresses the underpinning (generic) and job-specific skills that are required in the delivery of hotel front office tasks in hotels of comparable standard across a range of cultures and contexts. In undertaking this, the study will build on a previous pan-European study of hotel front office work (Baum and Odgers, 2001; Odgers and Baum, 2001). Hotel front office has been chosen because, while it is not the ‘lowest’ of the skills areas in hospitality, it represents an area where external and internal change have impacted greatly in recent years and where there is some evidence of changing skills expectations and technical deskilling among employers and educational providers.

The study comprises an international comparative study of front office work across both developed and developing country contexts, based on both quantitative and qualitative data. The outcomes of this ongoing study include detailed comparison of work, broadly within a common designation, in hotel front office, drawn from fieldwork in a number of locations as part of a study that will encompass approximately 15 locations worldwide upon its completion. The findings of this preliminary report on the research project explore the extent to which the skills expected and delivered are common across 7 selected locations where the study has been completed (Brazil, China, Egypt, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia and Northern Ireland). This forms the basis of tentative conclusions regarding the social and cultural construction of our understanding of skills and work in this area.

The hospitality sector is a case environment for the consideration of skills within the wider services sector. Despite its low status, it is one of the fastest growing sectors in the economy of most countries (developed and developing) and is challenging from a skills perspective in both bouyant and recessionary labour market conditions. Broad estimates suggest that up to 10 per cent of the global workforce are employed in hospitality-related work and, as a consequence, this is a sector that cannot readily be ignored. There is a significant coverage of the changing skills environment within the labour process literature, addressing issues such as deskilling (Elger, 1982), gender (Jenson, 1989), technology substitution (Cavestro, 1989; Coombs, 1985) and the development of skills though apprenticeship training (More, 1982). The focus in much of the literature, however, is on skills within traditional industrial sectors to the relative neglect of services. Consequently, attempts to classify skills (Noon and Blyton, 1995) are limited in their understanding of the nature of service work and the skills required in its delivery (Keep and Mayhew, 1999).

Many aspects of hospitality work have much in common with other areas of service delivery. There is, however, an argument that it is the context and combination of these skills that does generate unique attributes (see e.g. Lashley and Morrison, 2000 on the nature of hospitality; Hochschild, 1983; Morris and Feldman, 1996; Seymour, 2000 and their discussion of emotional labour; and the contribution of Warhurst et al., 2000 in adding the concept of aesthetic labour to the skills bundle in hospitality). Therefore, the debate about skills issues, in the context of hospitality, is informed by wider, generic consideration about skills in the context of changing employment, technology and vocational education, within both developed and developing economies. The major gap in understanding, which this study seeks to address, is the extent to which work which is perceived to be low skilled in the Western, developed context can be described in this way in other contexts because of differing cultural, communications, linguistic and relationship assumptions which underpin such work in developing countries.

Hospitality work in areas such as front office exhibits considerable variety. The traditional research focus on hospitality work concentrates on areas that provide, primarily, food and beverage (Gabriel, 1988; Mars and Nicod, 1984) and, to a lesser extent, accommodation. Coverage of this discussion is well served by reference to Wood (1997), Guerrier and Deery (1998) amongst others. Research in other areas of hospitality work, such as hotel front office, is much more poorly served (Bird et al., 2002; Vallen and Vallen, 2000) and this study draws on a limited range of work in these areas. The ‘newer’ areas include functions and tasks that exhibit considerable crossover with work that falls outside normal definitions of hospitality in food and drink manufacture: office administration, IT systems management and specialist areas of sports and leisure. Indeed, it is fair to say that, although there is long-standing debate as to whether the hospitality industry is ‘unique’ (Lashley and Morrison, 2000; Mullins, 1981), there is little doubt that there is little unique about hospitality skills. Most of the skills that are employed within the sector also have relevance and application in other sectors of the economy. Those employed in areas where there is considerable skills overlap with hospitality, such as the areas listed above, may well see themselves in terms of their generic skills area rather than as part of the hospitality labour market.

The characteristics and the organisation of the hospitality industry are subject to ongoing restructuring and evolutionary change. There are major labour market and skills implications of such change as businesses reshape the range of services they offer (Hjalager and Baum, 1998) or respond to fashion and trend imperatives in the consumer marketplace (Warhurst et al., 2000). Vertical diversity in hospitality work is represented by a more traditional classification that ranges from unskilled through semi-skilled and skilled to supervisory and management. This ‘traditional’ perspective of work and, therefore, skills in hospitality is partly described by Riley (1996) in terms that suggest that the proportionate breakdown of the workforce in hospitality at unskilled and semiskilled levels is 64 per cent of the total with skilled constituting a further 22 per cent of the total. Abdullah’s (2005) figures for Malaysia, while not based on directly comparable data, suggest that non-managerial positions break down into unskilled (19 per cent) and skilled/semi-skilled (42 per cent). These figures hint at a major difference in perceptions of skills within the sector between developed and developing economies.

These simplifications mask major business organisational diversity in hospitality, reflecting the size, location and ownership of businesses. The actual job and skills content of work in the sector is predicated upon these factors so that common job titles (e.g. restaurant manager, sous chef) almost certainly mask a very different range of responsibilities, tasks and skills within jobs in different establishments.

The skills profile of hospitality is influenced by the labour market that is available to it, both in direct terms and via educational and training establishments. The weak internal labour market characteristics in themselves impose downward pressures on the skills expectations that employers have of their staff and this, in turn, influences the nature and level of training which the educational system delivers. There is an evident cycle of down-skilling, not so much in response to the actual demands of hospitality or of consumer expectations of what it can deliver, but as a result of the perceptions of potential employees and the expectations that employers have of them.

Hospitality work is widely characterised in both the popular press and in research-based academic sources as dominated by a low-skills profile but Burns (1997) questions the basis for categorising hospitality employment into ‘skilled’ and ‘unskilled’ categories, arguing the postmodernist case that this separation is something of a social construct. This construct is rooted in, firstly, manpower planning paradigms for the manufacturing sector and, secondly, in the traditional power of trade unions to control entry into the workplace through lengthy apprenticeships. Burns bases this argument on a useful consideration of the definition of skills in hospitality, noting that:

the different sectors that comprise hospitality-as-industry take different approaches to their human resources, and that some of these differences…are due to whether or not the employees have a history of being ‘organised’ (either in terms of trade unions or staff associations with formalised communication procedures).

(Burns, 1997, p. 240)

This strong internal labour market analysis leads Burns to argue that skills within ‘organised’ sectors such as airlines and hotel companies with clearly defined staff relationship structures, such as the Sheraton, are recognised and valued. By contrast, catering and fast food ‘operate within a business culture where labour is seen in terms of costs which must be kept at the lowest possible level’ (Burns, 1997, p. 240) and where skills, therefore, are not valued or developed. Burns’ definition of hospitality and hospitality skills seeks to go beyond the purely technical capabilities that those using ‘unskilled’ or ‘low-skills’ descriptors assume.

This case is also argued by Poon (1993), who notes that new employees in hospitality:

Must be trained to be loyal, flexible, tolerant, amiable and responsible…at every successful hospitality establishment, it is the employees that stand out… Technology cannot substitute for welcoming employees.

(Poon, 1993, p. 262)

Burns’ emphasis on ‘emotional demands’ as an additional dimension of hospitality and hospitality skills has been developed in the work of Seymour (2000). Her work builds upon the seminal earlier work of Hochschild (1983) who introduced the concept of emotional work within the services economy. Hochschild argues that service employees are required to manage their emotions for the benefit of customers and are, in part, paid to do this. Likewise, Seymour recognises that what she calls ‘emotional labour’ is a concept of relevance to work in both fast food and traditional areas of service work. She concludes that both areas demand considerable emotional elements in addition to overt technical skills.

Burns rightly argues that the low-skills perspective of hospitality is context-specific and drawn from a Western-centric view of hospitality. He cites the inappropriateness of these assumptions when applied to environments such as the Soloman Islands, Sri Lanka and the Cook Islands. Likewise, Baum (1996) questions the validity of claims that hospitality is a work area of low skills. His argument is based on the cultural assumptions that lie behind employment in Westernised, international hospitality work whereby technical skills are defined in terms of a relatively seamless progression from domestic and consumer life into the hospitality workplace. In the developing world, such assumptions cannot be made as employees join hospitality and hospitality businesses without Western acculturation, without, for example, knowledge of the implements and ingredients of Western cookery. Learning at a technical level, therefore, is considerably more demanding than it might be in Western communities. Social and interpersonal skills also demand considerably more by way of prior learning, whether this pertains to language skills (English is a widespread prerequisite for hospitality and hospitality work in countries such as Thailand) or wider cultural communications. On the basis of this argument, Baum contends that work that may be unskilled in Europe and the USA requires significant investment in terms of education and training elsewhere and cannot, therefore, be universally described as ‘low skilled’. This issue is one that is beginning to assume significance in Western Europe as a combination of service sector labour shortages and growing immigration from countries of Eastern Europe and elsewhere means that skills assumptions in hospitality can no longer be taken for granted. The current hospitality labour market in the Republic of Ireland illustrates this situation where service standards are under challenge as the industry recruits staff from a wide range of former eastern bloc countries.

It is also useful, in summary of this section of the debate, to consider hospitality work in the light of the work of Noon and Blyton (1995). Their approach is to consider skills in terms of personal attributes, job requirements and the setting of work. This approach, with a focus on the context of work, both from an individual and organisational point of view, is much more sympathetic to the realities of diversity within hospitality work, as argued above by Burns and Baum. Noon and Blyton appear to accept that what is skilled work in one context may be less so in another, influenced by both the cultural context of the work and also by the availability and application of technology. It is argued, therefore, that a simple labelling of hospitality work as ‘unskilled’ is both unhelpful and unjustifiable.

This chapter reports initial findings from a study that will, eventually, permit comparison between some 15 locations worldwide. The methodology adopted within this study is common to all locations and is based on a self-completed questionnaire which looks at who hotel front office staff are, their backgrounds, training profiles, working experience and perceptions of skills and skills development. In each selected location, 4 star and 5 star hotels were selected (recognising that such star designations do not allow for truly accurate comparison) as those properties most likely to be operating in the international market. In most cases of fieldwork, the focus of the study is on a discrete location within the country, generally a large urban area, although two of the completed studies have a more national focus (China, Kenya). As a result of this approach, the number of participating hotels in each location varies significantly (in Kyrgyzstan, for example, only three properties could be identified that fitted into this classification), while the population in other locations was considerably greater.

The study was undertaken with the assistance of collaborating researchers in most locations. The choice of locations was, to a certain degree, opportunistic in that participation was determined by access to resources and personnel to conduct the study locally. Table 17.1 shows the study locations where the survey has been completed. However, further research is currently being undertaken in order to extend the scope of the study.

In conducting the survey, initial contact was with the general manager of intended sample hotels, seeking permission to conduct the survey locally in her/his property. Once permission was agreed, questionnaires were distributed for completion by all front office staff and collected at an agreed time by the researchers. In addition, where permission was granted, follow-up unstructured discussion on key survey themes was initiated with front office staff in order to probe these in greater depth although information from this aspect of the study is not presented in this paper. Response rates within individual hotels were high, ranging from 60 per cent to 100 per cent of those in the front office team.

Table 17.1 Research locations

| Country | Survey conducted | Data analysed |

| Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek) | X | X |

| Northern Ireland (Belfast) | X | X |

| Egypt (Cairo) | X | X |

| Brazil (Curitiba) | X | X |

| Kenya (national) | X | X |

| Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur) | X | X |

| China (Shandong Province) | X | X |

Further locations are being sought to extend the scope of the study.

This chapter reports findings from seven locations: Brazil (Curitiba), China (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Jinan, Qingdao and Weihai), Egypt (Cairo), Kenya (Nairobi, Mombasa, Safari Lodges), Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek), Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur) and Northern Ireland (Belfast), in order to give a flavour of the outcomes of the wider survey.

Who are the Front Office Employees?

Responses were mainly received from front office staff in all three research locations across a range of levels: management and supervisory staff, senior and junior staff, and trainees. A small number of respondents worked in other front office functions such as portering (Table 17.2).

This finding is in partial agreement with Odgers and Baum (2001), who noted a weakening of traditional workplace hierarchies in front office, with a decline in the position of junior or assistant receptionists. Dependence on more junior positions remains evident in Kyrgyzstan (Table 17.3).

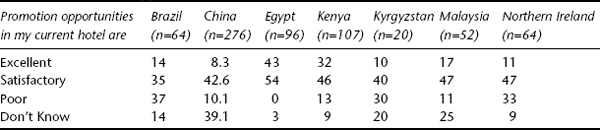

The gender breakdown points to very significant differences between the seven research environments, suggesting variation based on both cultural and economic factors. The female domination of front office work is consistent with Odgers and Baum’s (2001) survey of such work across eight Western European countries, but is also an interesting reflection of work in urban Chinese locations. In the former Soviet Republic of Kyrgyzstan, the predominant position of males in front office work is, on the face of it, surprising in that in the past this would have been an area dominated by female workers. However, the findings here point to male encroachment on areas of work which provide relatively well-paid opportunities in international companies. The Kenyan findings show the most balanced workforce in gender terms.

Table 17.2 Position of respondents (%)

Table 17.3 Gender of respondents (%)

Among front office employees in Malaysia, all respondents were full-time employees, working 48 hours or more per week and a similar picture emerges in China where 99.4 per cent of front office workers were full time. In Northern Ireland, all but five (8 per cent) of the respondents worked full time in the hotel front office, committing 39–49 hours per week to the job. In Kenya, all but one of the sample was in full-time employment. A similar pattern was found in Kyrgyzstan where 3 of the sample (15 per cent) were not full time. In Egypt, however, as many as 33 of the sample (34 per cent) were part-time employees, while in Brazil 33 per cent of employees interviewed were part-timers. Among these were most of the female respondents to the survey. Split shifts, a particularly unpopular model of working, were worked by 7 respondents (11 per cent) in Northern Ireland, by 10 (16 per cent) in Brazil, by 7 (35 per cent) in Kyrgyzstan, by 40 Kenyan respondents (37 per cent) and by 44 in Egypt (46 per cent).

Front Office Employees and Their Education

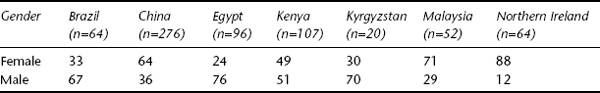

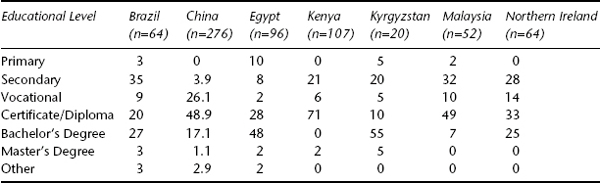

Very different patterns of educational attainment were evident across the seven survey respondents (Table 17.4). The Egyptian and Kyrgyz samples pointed to high levels (half or more) with university-level education, something rather less common in Brazil, China and Northern Ireland, the latter confirming the weakening of higher educational requirements for work of this nature across Western Europe (Odgers and Baum, 2001). The high number of those completing their education at secondary level is noticeable in Brazil but, at the same time, almost 50 per cent of the Brazilian sample had studied front office at some level before entering the industry. Specialist vocational education to diploma level dominates among Kenyan respondents, pointing to the strong role of the main educational provider for the sector in that country, Kenya Utalii College, in meeting the skilled labour market needs of the hospitality sector. A similar pattern is evident in Malaysia where the absence of graduates is particularly noticeable, perhaps reflecting the general demand for higher-level skills within that economy.

Working Experience of Front Office Employees

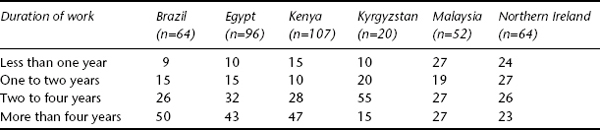

The hotel industry is widely associated with high levels of staff turnover. The findings from all seven survey samples contradict this generalisation and point to relative stability within front office teams, with over 70 per cent of Brazilian, Egyptian, Kenyan and Kyrgyz respondents having worked in their current hotel for over two years. In Malaysia, the comparable figure is 54 per cent while in Northern Ireland, it is 49 per cent (Table 17.5). In China, 75 per cent of the sample are working in their hotel of original employment.

Table 17.4 Educational attainment (%)

Table 17.5 Duration of work in current hotel (%)

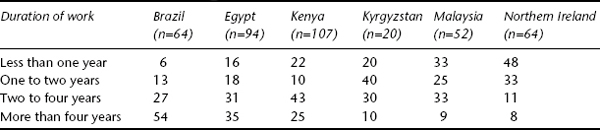

The patterns with respect to the time that front office staff have spent in their current positions are very different, however (Table 17.6). Brazilian, Egyptian and Kenyan staff are significantly more likely to have remained in their current post for two or more years (65+ per cent) than is the case in Malaysia (42 per cent), Kyrgyzstan (40 per cent) or Northern Ireland (19 per cent).

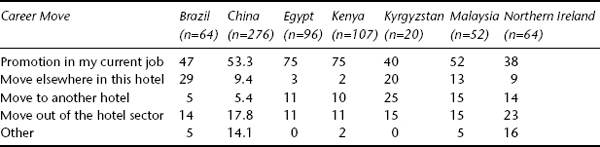

Table 17.6 certainly confirms relative stability within the front office workforce. Egyptian and Kenyan employees are, by a considerable margin, the most likely to seek promotion within their current work area. However, overall, 89 per cent of Egyptian and Kenyan respondents, 85 per cent of those from Kyrgyzstan and Malaysia and 81 per cent of those from Brazil see their future careers within the hotel sector (Table 17.7). By contrast, the comparable figure for China is 32 per cent and for Northern Ireland 39 per cent, potentially representing a significant skills loss to the sector.

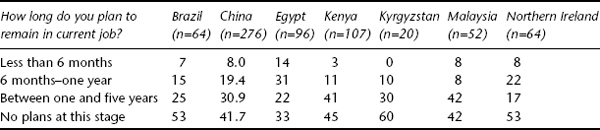

Table 17.8, reporting intentions to stay within respondents’ present job, indicates a significant degree of uncertainty within four of the sample workforces. Respondents from Egypt and Northern Ireland appear least committed to their current position, while those in emerging tourism destination countries appear most committed to their current employer.

Table 17.6 Duration of work in current position (%)

Table 17.7 Next career move (%)

Table 17.8 Plans to remain in current job (%)

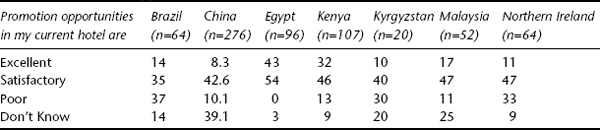

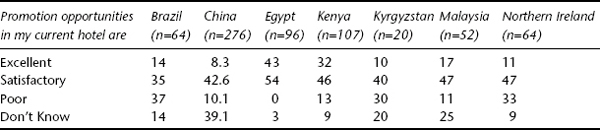

Table 17.9 Promotion opportunities (%)

Table 17.9 further points to the positive career perspective of front office employees in Egypt and Kenya, with 97 per cent and 78 per cent respectively believing promotion opportunities to be excellent or satisfactory. Comparable figures for Brazil, China, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia and Northern Ireland are 49 per cent, 50 per cent, 64 per cent and 68 per cent, reflecting rather greater uncertainty within these working groups.

Perspectives of Work in Hotel Front Office

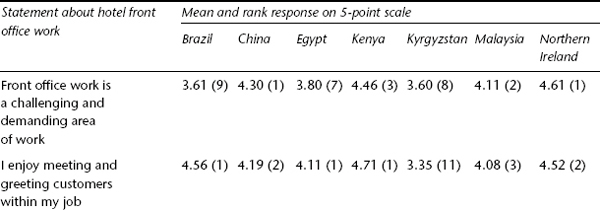

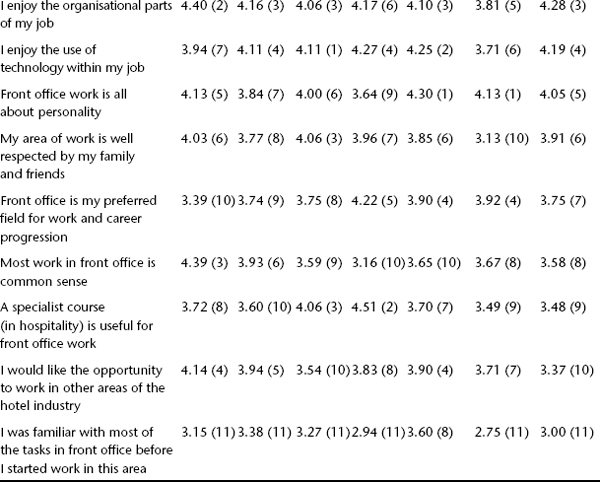

Respondents were asked to respond to statements about working in hotel front office, based on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 equates to ‘Disagree Strongly’ and 5 equates to ‘Agree strongly’ (Table 17.10). The ranking pattern of responses shows major differences, while actual ratings also vary significantly between the seven samples in terms of the range of means generated within each survey. What is interesting is the differing levels of correlation between the sample responses. The very close correlation between China and Northern Ireland in this context is particularly noticeable. The Kyrgyz ranking of hotel work attributes appears to show virtually no relationship to those of the other five samples whereas comparison of some of the responses from Brazil, Egypt, Kenya, Malaysia and Northern Ireland show rather greater similarity although not statistically significant at the 5 per cent level.

Table 17.10 Working in hotel front office

Rank order correlations within the seven sample responses

Spearman’s r for:

Brazil and Egypt = +0.36

Brazil and China = +0.55

Brazil and Kenya = +0.15

Brazil and Kyrgyzstan = -0.08

Brazil and Malaysia = +0.45

Brazil and Northern Ireland = +0.34

China and Egypt = +0.29

China and Kenya = +0.49

China and Kyrgyzstan = -0.04

China and Malaysia = +0.62

China and Northern Ireland = +0.81

Egypt and Kenya = +0.69

Egypt and Kyrgyzstan = +0.03

Egypt and Malaysia = +0.44

Egypt and Northern Ireland = +0.57

Kenya and Kyrgyzstan = -0.06

Kenya and Malaysia = +0.55

Kenya and Northern Ireland = +0.63

Kyrgyzstan and Malaysia = +0.17

Kyrgyzstan and Northern Ireland = +0.03

Malaysia and Northern Ireland = +0.72*

* = Significant at the 5% level

Importance of Specific Skills within Front Office Work

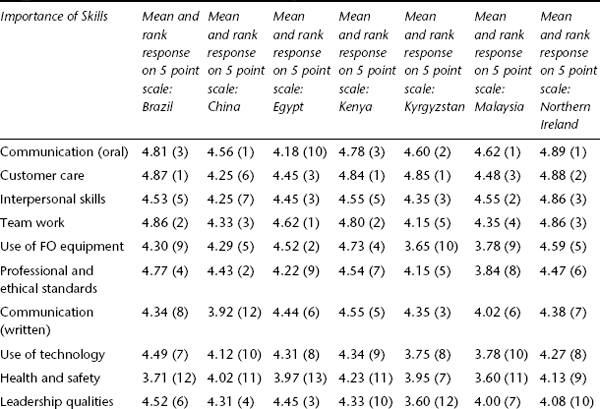

Respondents were asked to respond to statements about skills required for work in hotel front office, based on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 equates to ‘Very low importance’ and 5 equates to ‘Very important’ (Table 17.11). Significant variations were found in the mean and ranking of skills by the four samples. Correlations based on the ranking of skills shows relatively close agreement between respondents from across all samples with the exception of Egypt and Kyrgyzstan.

Significance levels point to similarities across pairings that appear to cross cultural, economic and tourism sector differences. For example, perceptions of the relative importance of specific skills is close between Malaysia and Brazil, Kenya and Northern Ireland. The Chinese findings, however, point to similarities in responses to both less- and more-developed environments. The findings, overall, point to some consensus across environments with regard to how front office work is perceived.

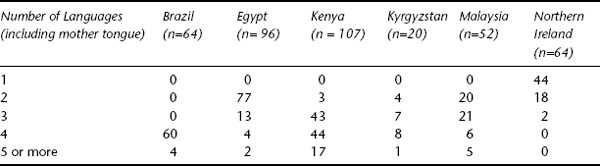

Consideration of skills which might be considered of considerable importance to work in hotel front office, that of languages, points to findings which are very consistent with those of Odgers and Baum (2001), who noted that in English speaking countries far fewer front office staff are equipped to communicate with guests who may not wish to communicate in the local language (Table 17.12). In both Egypt and Kyrgyzstan, hotel staff are far more likely to have skills across a range of languages beyond their mother tongue than are their counterparts in Northern Ireland. The findings with respect to Brazil are the most dramatic, with the full sample claiming levels of functional fluency in four languages, including their native Portuguese.

Table 17.11 Importance of skills in front office work

Rank order correlations within the seven sample responses

Spearman’s r for:

Brazil and Egypt = +0.40

Brazil and China = +0.69

Brazil and Kenya = +0.77*

Brazil and Kyrgyzstan = +0.58

Brazil and Malaysia = +0.74*

Brazil and Northern Ireland = +0.76*

China and Egypt = +0.29

China and Kenya = +0.50

China and Kyrgyzstan = +0.21

China and Malaysia = +0.53

China and Northern Ireland = +0.61

Egypt and Kenya = +0.64

Egypt and Kyrgyzstan = +0.10

Egypt and Malaysia = +0.52

Egypt and Northern Ireland = +0.48

Kenya and Kyrgyzstan = +0.66

Kenya and Malaysia = +0.80*

Kenya and Northern Ireland = +0.92*

Kyrgyzstan and Malaysia = +0.59

Kyrgyzstan and Northern Ireland = +0.78*

Malaysia and Northern Ireland = +0.78*

* = Significant at the 5% level

Table 17.12 Fluency in languages (n)

Language skills in Kenya reflect the multilingual culture of that country. A very significant majority of respondents were fluent in three languages, namely their tribal language, Kiswahili and English; a wide range of additional African and European languages were reported in addition. Within the Chinese sample, although some respondents reported limited English, Japanese and Korean skills, overall only a small minority were able to function with languages other than Mandarin and/or their regional dialect.

In this chapter, a flavour of comparative outcomes is presented, with only limited attempts to speculate about the reasons why differences exist within the data sets generated by the four studies. For a variety of reasons, the data here has limitations, not least because of the sample size from one of the studies based as it is on the only international standard hotels in the research location. However, at this point, it is possible to draw a number of tentative inferences from the data analysed:

In some respects, these findings may appear to confirm anticipated differences in work and perceptions of work that are the result of a combination of economic, political, cultural and other factors. Further data analysis will enable a clear picture to emerge and permit the extraction of firmer conclusions. These preliminary findings are of considerable importance in that they provide justification for further development of this project along the lines indicated earlier in this chapter. Notwithstanding the apparent attempts of multinational companies and major development agencies that generally assume otherwise, this paper suggests that there is evidence to support the contention that hotel work, specifically in front office, is socially constructed and needs to be viewed from a more context-driven perspective.

Abdullah, L. A. (2005) ‘The potential of the human resources in the Malaysian hospitality environment: The way ahead in the 21st century’. In Proceedings of the Third Asia-Pacific CHRIE (APacCHRIE) Conference 2005. Kuala Lumpur: CHRIE, pp. 777–88

Baum, T. (1996) ‘Unskilled work and the hospitality industry: Myth or reality?’. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 15(3), 207–9

Baum, T. (2002) ‘Skills and training for the hospitality sector: A review of issues’. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 54(3), 343–63

Baum, T. and Odgers, P. (2001) ‘Benchmarking best practice in hotel front office: The Western European experience’. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, 2(3/4), 93–109

Bird, E., Lynch, P. and Ingram, A. (2002) ‘Gender and employment flexibility within hotel front office’. The Service Industries Journal, 22(3), 99–116

Brown, P., Green, A. and Lauder, H. (2001) High skills: Globalization, competitiveness and skill formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Burns, P. M. (1997) ‘Hard-skills, soft-skills: Undervaluing hospitality’s “service with a smile”’. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(3), 239–48

Cavestro, W. (1989) ‘Automation, new technology and work content’. In S. Wood (ed.) The transformation of work. London: Unwin Hyman, pp. 219–34

Coombs, R. (1985) ‘Automation, management strategies and the labour process’. In D. Knights, H. Willmott and D. Collinson (eds) Job redesign: Critical perspectives on the labour process. Aldershot: Gower, pp. 142–70

Elger, T. (1982) ‘Braverman, capital accumulation and deskilling’. In S. Wood (ed.) The degradation of work? Skilling, deskilling and the labour process. London: Hutchinson, pp. 23–53

Gabriel, Y. (1988) Working lives in catering. London: Routledge

Guerrier, Y. and Deery, M. (1998) ‘Research in hospitality human resource management and organizational behaviour’. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 17(2), 145–60

Hjalager, A.-M. and Baum, T. (1998) Upgrading human resources: An analysis of the number, quality and qualifications of employees required in the hospitality sector. Brussels: Commission of the European Union

Hochschild, A. R. (1983) The managed heart: Commercialisation of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

Jenson, J. (1989) ‘The talents of women, the skills of men: flexible specialization and women’. In S. Wood (ed.) The transformation of work? Skill, flexibility and the labour process. London: Routledge, pp. 141–55

Keep, E. and Mayhew, K. (1999) Skills task force research paper 6: The leisure sector. London: DfEE

Lashley, C. and Morrison, A. (eds) (2000) In search of hospitality. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann

Mars, G. and Nicod, M. (1984) The world of waiters. London: Allen and Unwin

More, C. (1982) ‘Skill and the survival of apprenticeship’. In S. Wood (ed.) The degradation of work? Skill, deskilling and the labour process. London: Hutchinson, pp. 76–93

Morris, J. and Feldman, D. (1996) ‘The dimensions, antecedents and consequences of emotional labor’. Academy of Management Review, 21, 986–1001

Mullins, L.J. (1981) ‘Is hospitality unique?’. Hospitality, September, pp. 30–33

Nickson, D., Warhurst, C. and Witz, A. (2003) ‘The labour of aesthetics and the aesthetics of organization’. Organization, 10(1), 33–54

Noon, M. and Blyton, P. (1995) The realities of work. Basingstoke: Macmillan

Odgers, P. and Baum, T. (2001) Benchmarking of best practice in hotel front office. Dublin: CERT

Poon, A. (1993) Hospitality, technology and competitive strategies. Wallingford: CAB

Riley, M. (1996) Human resource management in the hospitality and tourism industry (2nd edn). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann

Seymour, D. (2000) ‘Emotional labour: A comparison between fast food and traditional service work’. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19(2), 159–71

Shaw, G. and Williams, A. (1994) Critical issues in hospitality: A geographical perspective. Oxford: Blackwell

Vallen, G. K. and Vallen, J. J. (2000) Check in, check out: Front office management (6th edn). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall

Warhurst, C., Nickson, D., Witz, A. and Cullen, A. M. (2000) ‘Aesthetic labour in interactive service work: Some case study evidence from the “New Glasgow”‘. Service Industries Journal, 20(3), 1–18

Westwood, A. (2002) Is new work good work? London: The Work Foundation

Wood, R. C. (1997) Working in hotels and catering (2nd edn). London: Routledge