If you really want to get to know Cyprus, rather than just soak up sun on its beaches, you should stay in more than one place. If your base is at one of southern Cyprus’ extremities – Pafos or Agia Napa – it’s a good idea to spend a few nights at a more central coastal location around Limassol, or to go inland to Nicosia or the Troödos Mountains. You may also want to set aside time for the North, where the best overnight options are around Keryneia or on the Karpaz Peninsula.

Rapid transit

The motorway network linking Nicosia and all the coastal resorts in South Cyprus makes for speedy transfers, but there’s much to be said for pottering along on a slower route.

Café life in Nicosia

iStock

Nicosia and Environs

Nicosia (Lefkosia in Greek, Lefkoşa in Turkish) 1 [map] is Cyprus’ only major city in the interior, occupying the site of ancient Ledra, founded in the 3rd century BC by Lefkonas, son of Ptolemy I of Egypt. When coastal Paphos and Salamis (Constantia) came under Arab attack during the 7th century AD, the population moved inland and Nicosia became the chief city. Under the Lusignans, it grew into a splendid capital marked by elegant churches and monasteries in the French Gothic style.

Almost everything of interest to tourists lies within, or just outside, the old city walls. The ramparts, built by the Venetians in preparation for the Turkish invasion of 1570, remain Nicosia’s dominant feature. The wheel-shaped Renaissance fortification has become the modern capital’s distinctive logo, with its 11 pointed bastions and three gateways named after the coastal cities to which they lead – Famagusta Gate to the east, Pafos Gate to the west and Keryneia (Girne) Gate to the north. Some of the bastions now shelter municipal offices, while sections of the (now dry) moat serve as public gardens and car parks.

Since the Turkish invasion of 1974, Nicosia remains a divided city, roughly half in Southern Cyprus, half in the North; the ‘Green Line’ buffer zone that straddles the dividing line, with its derelict 1930s buildings, UN, Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot checkpoints, barbed wire, sandbags and roadblocks, is an eerie reminder of this. However, the Cypriot capital is experiencing something of a rebirth. Both tourists and Cypriots can now pass with relative ease between the two halves at the three local official crossing-points.

Many visitors spend just a day here, but an overnight stay (or more) is well worthwhile if you want to explore both halves of the fortified city properly – and experience some of the best dining opportunities on the island. Be prepared for real summer heat – Nicosia is around three or four degrees hotter than the coast, with temperatures soaring to 37°C (99°F) in July.

Clear waters near Agia Napa

iStock

The island’s finest collection of antiquities is housed in the Cyprus Museum A [map] (Tue–Fri 8am–6pm, Sat 9am–5pm, Sun 10am–1pm, first Wed of month until 8pm) on Leoforos (Avenue) Mouseiou, just west of the walled city near the Pafos Gate. The neoclassical building houses archaeological artefacts dating from the Stone Age (around 8000 BC) to the Roman era, though the most riveting displays are of Bronze Age and Archaic vintage. Ground will eventually be broken across the road for a purpose-built annexe, linked to the existing building by an underpass or aerial bridge; the guards may proudly tell you that items in storage could fill four museums of comparable quality.

Exhibits from the early Bronze Age, in Room 2, include the so-called sanctuary model (2000 BC), in which worshippers and priests attend a bull sacrifice while a peeping Tom on the sanctuary wall watches the secret ceremony. In Room 3, an intriguing Mycenaean krater (drinking cup) imported to Enkomi in the 14th century BC has an octopus motif framing a scene of Zeus preparing warriors for battle at Troy; nearby, a beautiful green faïence rhyton (ritual drinking vessel) of the 12th century BC depicts a lively bull-hunt in Kition.

Cyprus’ Terracotta Army

Perhaps the most memorable exhibit in the Cyprus Museum is the ‘Terracotta Army’, consisting of over 500 votive statues and figurines dating from between 625 and 500 BC (an equal number were taken to Stockholm by the Swedish excavators). Found at Agia Irini in northwest Cyprus, the figurines are displayed as they originally stood, around the altar of an open-air sanctuary dedicated to a dual cult of war and fertility. Soldiers, war chariots, priests with bull masks, sphinxes, minotaurs and bulls were fashioned in all sizes, from life-size to just 10cm (4ins) tall, and at various levels of workmanship, according to the wealth of the donor.

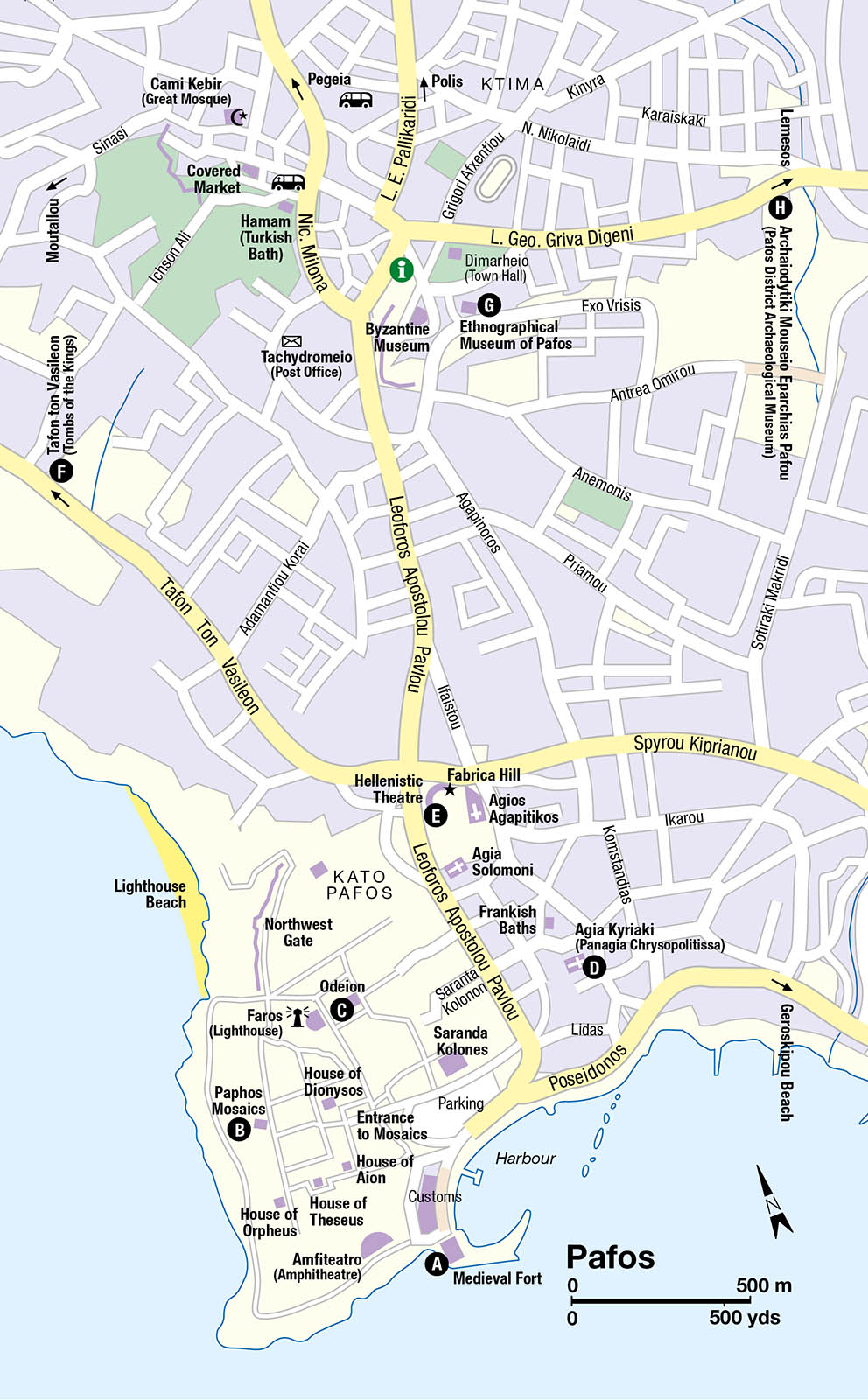

Room 5 has a rich collection of sculpture, and the highlight is a trio of magnificent lions, tongues and teeth bared, plus two sphinxes, discovered in 1997 guarding tombs at Tamassos. Left of these is a double-sided limestone stele depicting Dionysos on one side, and on the other, facing the wall, an erotic scene leaving nothing to the imagination. At the far end of the hall, a sensuous marble Aphrodite has become the logo of island tourism despite having lost her arms and lower legs.

The monumental bronze of Roman Emperor Septimius Severus (c.AD 200) dominates Room 6, among other marble and bronze sculptures. Highlights of Room 7 include the ‘Horned God’ from Enkomi, one hand downturned in a blessing gesture, and gold pieces from the Lambousa Treasure Hoard. Up short stairs in Room 11 is some fascinating royal tomb furniture from Salamis (8th century BC): an ivory throne, a bed, ornamentation for two funerary chariots and their horses’ tackle.

Statue of Aphrodite

George Taylor/Apa Publications

Along Odos Lidras

The old city’s principal thoroughfare and main pedestrianised shopping street, Lidras (Ledra Street), runs north from Plateia Eleftherias to the Ledra/Lokmacı crossing. Just off its southern end, at Ippokratous 17, stands the award-winning Leventis Municipal Museum of Nicosia B [map] (www.leventismuseum.org.cy; Tue–Sun 10am–4.30pm; free but donation appreciated), three floors of a fine 19th-century neoclassical mansion devoted to the city’s history as reflected in privately donated archaeological collections, Lusignan pottery, metal utensils, old engravings and posters, displays on trades or crafts, and worthwhile temporary exhibitions.

Just east of the museum spreads the so-called Laïki Geitonia (Traditional Pedestrian Neighbourhood), which purports to recreate old Nicosia through various buildings in traditional style, some restored, others purpose-built, house galleries, cafés and tavernas, the latter eminently avoidable. A tourist trap, in short; the real rescue of the long-neglected old town is taking place on other streets, through private, state and UN initiatives.

Plateia Eleftherias

Most visitors to the old city enter via Plateia Eleftherias, a prominent square just southwest of the walled city that has been in the throes of a Zaha Hadid-designed makeover since 2008. The project was scheduled for completion in 2016, but cost overruns along with technical and contractual delays leave the completion to be determined; you can see what the finished project will look like at www.zaha-hadid.com/masterplans/eleftheria-square.

Slightly further up Lidras, the Shacolas Tower Museum & Observatory (daily summer 10am–7pm, closes earlier Sept–May) is located on the top floor of the sixth tallest building in Nicosia. The first five floors are occupied by an H&M and from the museum and observatory on the top floor there are excellent views of the whole city, though the ‘museum’ bit is rather bogus, consisting merely of poor reproductions of archival photos.

East of, and parallel to, Lidras is pedestrianised Onasagorou, less chain-store dominated and with interesting restaurants or cafés. It leads north to the landmark church of Panagia Faneromeni (open irregularly; free), dating from 1872 in its present form and last resting place of the four bishops executed in 1821. Nearby is the chunky but handsome Araplar Mosque, usually closed to the public and actually the converted 16th-century church of Stavros tou Missirikou.

The Archbishop’s Palace and Around

Linchpin of eastern Greek Cypriot old Nicosia is the Archbishop’s Palace on Plateia Archiepiskopou Kyprianou, a grandiose pastiche built during the 1980s to replace its predecessor, destroyed by EOKA-B during its July 1974 putsch. The only portions of it generally open to the public, at the rear right as you face it, are the Byzantine Museum and Art Galleries C [map] (Mon–Fri 9am–4.30pm, Sat except Aug 9am–1pm). The upper storey with its second-rate collection of religious paintings is distinctly optional, but the ground-floor galleries are essential viewing. Assembled there are superb icons rescued from all over Cyprus, but the main stars are towards the rear. Don’t miss the display of seven splendid 6th-century mosaics from Panagia Kanakaria church in Northern Cyprus, recovered through court action during the 1980s and 1990s, after having been looted and offered for sale on the international art market. Immediately adjacent are the best 15th-century frescoes from Antiphonitis Monastery in the North, recovered in 1997 after having been similarly looted and illegally exported. In another corner is more newly arrived repatriated art: magnificent 13th-century frescoes from the chapel of Agios Evfimianos at Lysi in the North, comprising a Christ Pandokrator in a dome, and a Virgin flanked by angels in an apse, remounted exactly as they were in their original setting.

Next to this museum is Agios Ioannis (Mon–Fri 8am–noon and 2–4pm, Sat 9am–noon; free), Nicosia’s small Orthodox cathedral, built in 1662 in an approximation of Late Gothic style on the site of a former Lusignan Benedictine monastery. Its colourful 18th-century frescoes depict key moments in the island’s early Christian history. The adjacent Gothic-arcaded building, all that remains of the 13th-century monastery, is now the Cyprus Folk Art Museum (Mon–Fri 9.30am–4pm, Sat 9am–1pm), full of wooden water wheels, looms, pottery, carved and painted bridal chests, lace, embroidered costumes and much else besides.

Inside the House of Hadjigeorgakis Kornesios

Alamy

Next door the National Struggle Museum (Mon–Fri 8am–2.30pm, times subject to change without notice; free), minimally labelled in English – it’s meant mostly for Greek Cypriot schoolchildren – glorifies EOKA’s campaign of shootings, sabotage and demonstrations, as well as documenting the harsh British reprisals. Displays include cartoons, witty graffiti, newspaper clippings, final letters of condemned prisoners and EOKA fighters’ belongings.

Immediately west of the Ethnographic Museum along Palias Ilektrikis stands the Nicosia Municipal Arts Centre D [map] (Tue–Sat 10am–9pm; free) the city’s primary modern-art museum, universally known as the Palia Ilektriki (‘Old Electric’) from its being a converted power plant. The centre focuses on promoting fine arts and its constantly changing exhibits are generally compelling, plus there’s a popular restaurant on the premises.

An icon of Christ on display at the Byzantine Museum

Jon Davidson/Apa Publications

To experience a more successful rejuvenation project than Laïki Geitonia, it’s worth strolling from the vicinity of the Archbishop’s Palace towards the far northeasterly corner of the Greek-Cypriot old town, where the contiguous neighbourhoods of Tahtakale (with a fine old mosque) and Chrysaliniotissa (Khrysaliniotissa) have had their Ottoman-era mansions and humbler houses repaired and painted in a varied palette, and their interiors renovated to serve as housing for families. Heart of the latter district is the originally Lusignan church of Panagia Chrysaliniotissa E [map] (Our Lady of the Golden Flax). First thought to be built in 1450, it is rarely open, but the finely carved exterior is the main attraction, with most of its interior art now safely in the Byzantine Museum.

Immediately southeast of Tahtakale and Chrysaliniotissa is the massive tunnel-like Famagusta Gate F [map] (Mon–Fri May–Sept 10am–1pm and 5–8pm, Oct–Apr 10am–1pm and 4–7pm; free), originally the main entrance to the medieval city. Restored during the early 1980s as the first of the local gentrification projects, it now operates as a cultural centre. The masoned barrel vaults provide an atmospheric setting for concerts, plays and art exhibitions.

Two blocks south of the Archbishop’s Palace, at Patriarchou Grigoriou 20, the House of Hadjigeorgakis Kornesios (Ethnological Museum) G [map] (Tue–Fri 8.30am–3.30pm, Sat 9.30am–4.30pm) is a beautiful 1793 structure with a Gothic-style doorway and overhanging, enclosed balcony. The thoroughly renovated Ottoman-style interior is notable for its period furnishings, ornate stairway and grand reception room. It attests the wealth of Kornesios, the dragoman or official mediator between the Turkish sultan and Cypriot archbishop.

A short walk west along Patriarchou Grigoriou brings you to Plateia Tillyrias, dominated by the Ömeriye Mosque H [map], transformed from the Augustinian monastic church of St Mary’s by the Ottoman conquerors. The mosque is still used for Muslim worship but is open to visitors outside of prayer times. The late 16th-century hamam or Turkish bath across the square has been meticulously restored, and functions as a contemporary spa with a full range of treatments available (Hamam Omerye, www.hamamomerye.com; Wed–Sun 10.30am–8.30pm, Mon–Tue by appointment).

Selimiye Mosque

Shutterstock

Compared with the bustling southern half of the city, northern Nicosia is quieter and poorer, though this is changing fast. The Lidra/Lokmacı pedestrian crossing point is conveniently close to a cluster of the most interesting sights in the North, making even the shortest visit worthwhile.

From much of the city, you will glimpse the minarets of the Selimiye Camii I [map] (Selimiye Mosque or Aya Sofya; daily dawn–dusk; donation expected), which was formerly the Gothic Cathedral of the Holy Wisdom, begun in 1209 and consecrated in 1326 (though never actually completed). Here, Lusignan rulers were crowned kings of Cyprus; the Ottomans turned it into a mosque after the 1570 conquest, whitewashing over all the figural imagery but leaving soaring arches intact.

Next door, the Bedesten J [map] began life as a 6th-century Byzantine church before being enlarged as the Catholic church of St Nicholas of the English during the 14th century. Under the Ottomans it served briefly as a grain store and lockable cloth market before being abandoned. It emerged in 2009 from UN-sponsored (and EU- and Evkaf-funded) renovation, so you can once again admire the building’s glory – the magnificent north portal with its relief carving. Across the street is a functioning bazaar, the Belediye Pazari (Municipal Market), widely known as the Bandabulya. It was recently rebuilt for structural reasons, but at the cost of its former atmosphere – and the expulsion of most of the old stallholders. Across Selimiye Meydanı, beyond the apse of the Selimiye Camii, stands the Lapidary Museum K [map] (Mon–Fri summer 9am–2pm, winter 9am–1pm and 2–4.45pm), a Lusignan building filled with intricately carved stonework of every description.

West of the mosque, Asma Altı Sokağı leads past a couple of old Turkish hans (courtyarded inns). The Büyük Han L [map] (Great Inn) – now home to small art galleries, workshops, and a café-restaurant – one of the oldest (1572) purpose-built Ottoman structures on the island, has been thoroughly and tastefully restored. The nearby Kumarcılar Hanı (Gamblers’ Inn) was fully restored in 2018, and now hosts a café/restaurant and some small shops. Also nearby is the Büyük Hamam (Great Bath; Tue–Sun 9am–9pm), a converted Lusignan church, which, like its South Nicosia counterpart, has been thoughtfully overhauled. At the far end of Asma Alti Sokağı is Sarayönü Square, officially Atatürk Square M [map], the hub of Turkish-Cypriot Nicosia. Its central granite column was probably brought from Salamis by the Venetians.

From the square, head north along Girne Caddesi to the Mevlevî Tekke N [map] (Mon–Fri summer 9am–2pm, winter 9am–1pm and 2–4.45pm). This was once a ceremonial hall used by the Mevlevî ‘whirling dervish’ sect, outlawed in Turkey in 1925 but surviving in Cyprus until 1954. The multi-domed, 17th-century building now has displays on the dervishes’ daily life, including mannequins holding the musical instruments essential to the whirling ceremony. The building itself is the star exhibit, but an arresting sight is the room packed with the tombs of 16 Mevlevî sheiks. Near here, the Keryneia Gate (Girne Kapısı) is northern Nicosia’s only original Venetian gate, built in 1567, restored in 1821, but isolated since 1931 when the British cut great gaps in the walls to either side to permit passage of traffic to the rest of Northern Cyprus.

Limestone sculptures unearthed at Tamassos, displayed in the Cyprus Museum in Nocosia

Alamy

Around South Nicosia

The following excursions all lie within 50km (30 miles) of southern Nicosia, making them easy day trips.

Tamassos Archaeological Site (Mon–Fri mid-Apr–mid-Sept 9.30am–5pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–4pm) 2 [map], an ancient city-kingdom dependent on copper mining, is just over 20km (12 miles) southwest of the capital, near the village of Politiko. Here excavations have uncovered a sanctuary and altar dedicated to Aphrodite/Astarte; although its importance is difficult to appreciate given its currently ruinous state, the discovery of copper traces in the temple demonstrated that metallurgy was sacred and that priests may have controlled the enterprise. Of more general interest are two royal tombs (6th century BC). In each, stairways descend to a narrow dromos – a passage carved in stone to imitate wooden surfaces, complete with simulated bolted doors, window sills and ‘log-roof’ ceilings. A set of magnificent stone lions and sphinxes which guarded the tombs are on display at the Cyprus Museum (for more information, click here).

From here a scenic, back-road drive leads to the monastery of Machairas (Makherás) 3 [map], 884 metres (2,900ft) up in the rugged Pitsilia region (church open daily for pilgrims 8.30am–5pm, until 6pm May–Oct; free; no cameras or videos). The monastery itself is a modern construction; an 1892 fire destroyed the original 12th-century foundation, although an allegedly miracle-working icon of the Virgin survived, and modern frescoes are of a high standard.

The region (and the monastery itself) was a hideout for EOKA’s second-in-command Grigoris Afxentiou, who was burnt alive at the conclusion of a protracted battle with the British near the monastery in 1957. The site of his death (a cave just below the monastery) is decorated with wreaths and is a place of pilgrimage for Greek Cypriots; inside the monastery a one-room museum documents the man and his grisly end.

Down the road beyond Lazanias and Gourri, the officially protected but rather lifeless village of Fikardou (Fikárdhou) represents a worthy effort to sustain Cypriot rural traditions, rating as a Unesco World Heritage Site. Its subtly coloured 18th- and 19th-century stone and mud-straw houses along cobbled streets have been restored with intent to revitalise the community. Alas, it does not seem to be working; in 1992, when the scheme was in its infancy, there were just eight permanent residents, and the population has remained at about the same number. Wend your way past the church to the museum-houses of Katsinioros and Achilleas Dimitri (daily mid-Apr–Oct 9.30am–5pm, Nov–mid-Apr 8.30am–4pm), where you can see authentic old furnishings, a spinning wheel and loom, an olive press and a zivanía still.

Asinou Church

Stranded somewhat in the middle of nowhere just outside Nikitari, 50km (31 miles) west of Nicosia, is Panagia Asinou 4 [map], also known as Panagia Forviotissa (Our Lady of the Meadows; Mon–Sat 9am–4pm, Sun 11am–4pm, free but donation appreciated), one of the gems of the Troödos foothills. From Nicosia take the road beyond Peristerona, then follow the signs to the 12th-century hillside church, famous for its magnificent Byzantine frescoes (also for more information, click here).

This modest but exquisite little stone-built, pitch-roofed church contains a veritable gallery of Byzantine art from the 12th century, some skilfully overpainted 250 years later. A booklet explaining the different styles and subjects of the frescoes is usually available. Failing that, the highlights are a complete cycle of the life of Christ in the middle recess of the ceiling, and the apsidal frescoes of the Virgin flanked by archangels and Christ offering Communion to the apostles. If you find the church closed go back to the village of Nikitari and search out the local priest who looks after the key – either in the central café, or by phoning tel: 99 830329.

Larnaka’s Agios Lazaros

Shutterstock

Larnaka and the East

Sprawling along the western shore of the wide bay that bears its name, Larnaka (Larnaca) 5 [map] retains a holiday resort atmosphere while at the same time hosting Cyprus’ main international airport and the country’s second busiest port (after Limassol).

Much of northern Larnaka is built over the ancient city-kingdom of Kition. Legend attributes its founding to the Phoenician Kittim, a grandson of Noah, but Mycenaean dwellings discovered from the 2nd millennium BC make this the oldest continuously inhabited city in Cyprus. The Phoenicians prospered here from the export of copper, and many centuries later Lusignan barons revived the town as a commercial and shipping centre. Under the Ottomans, foreign merchants and the consulates needed to protect their interests gave the town a cosmopolitan air.

The Seafront

The palm-lined Foinikoudes (Finikoúdhes, ‘Palm Trees’) Promenade is home to hotels, chic cafés and fast-food eateries; at the north end is the pleasure-boat marina. A bust of the Athenian commander Kimon, who led a fleet to recapture Kition from the Persians in 450 BC (but died in the attempt), is a reminder of an ancient past.

Turbanned tombstones in the Cami Kebir’s graveyard

Caroline Jones/Apa Publications

From the marina, the compacted, dark-sand town beach stretches almost to the old fort that marks the edge of what was the Muslim quarter. Larnaka Fort (mid-Apr–mid-Sept Mon–Fri 8am–7.30pm, Sat–Sun 9.30–5pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr Mon–Fri 8am–5pm, Sat–Sun 9.30–5pm), originally Lusignan but adapted by the Ottomans, houses exhibits from its own history and serves as a venue for cultural events. From the ramparts, there are good views of the coastline. Opposite is the Cami Kebir (Great Mosque; dawn–dusk; donation expected), a converted Lusignan church still functioning as a place of worship for local Egyptians, Syrians and Iranians. Notice the tombstones topped with stone turbans in the graveyard, a rare sight so close to a mosque.

Agios Lazaros

Some 300 metres/328 yards inland from here looms the three-tiered campanile of the town’s most revered church, Agios Lazaros (daily Mar–Oct 8am–6.30pm, Nov–Feb 8am–12.30pm and 2.30–5.30pm; free but donation appreciated), dedicated to the man the New Testament tells us Jesus raised from the dead. According to legend, the locals of Bethany, his home town, were decidedly unimpressed by the miracle, expelling Lazarus in a not particularly seaworthy boat that nevertheless got him as far as Kition. Here, where he was more appreciated, Lazarus settled, became bishop and some 30 years later died (this time for good). The church erected over his tomb has been rebuilt many times, most recently in an extravagant mix of Byzantine, Romanesque and Gothic styles, and it has a fine iconostasis. The purported remains of Lazarus were taken from here to Constantinople in 898; in the crypt below the iconostasis you can see the empty but still venerated sarcophagus.

Hala Sultan Tekke, the island’s most important Muslim shrine

Shutterstock

Larnaka’s Museums

Opposite the marina, housed in refurbished former customs warehouses, are the Larnaka Municipal Cultural Centre (Mon–Fri 10am–1pm and 4–7pm, Sat 10am–1pm; free), whose art gallery has a changing programme of exhibits by local and foreign artists. Across from the nearby tourist office, on Zinonos Kitieos, is the town’s best private collection, the Pierides Marfin Laïki Bank Museum (www.pieridesfoundation.com.cy; Mon–Thur 9am–4pm, Fri–Sat 9am–1pm). Housed in an old family mansion are hundreds of archaeological finds and works of art from all over the island, tracing Cypriot culture from Chalcolithic to Lusignan times. Highlights include the famous ‘Howling Man’ of 3000 BC from Souskiou, painted Archaic and Attic pottery, cruciform picrolite idols, an antiquarian map gallery, Byzantine and Lusignan glazed ceramics, Roman glassware and Cypriot embroidery.

Larnaka District Archaeological Museum (Mon–Fri 8am–4pm, Sat 9am–4pm) is a 10-minute walk northwest of the city centre beyond Leoforos (Avenue) Grigori Afxentiou, on Kimonos opposite the handsome Catholic convent of St Joseph. Of principal interest here are a reconstructed tomb from nearby Choirokoitia (for more information, click here), and Bronze Age pottery, in particular an amphora with a rampant octopus, and a krater (wine goblet) in the form of a fish.

West of Larnaka

About 3km (2 miles) southwest of the town, in the direction of the airport, lies the Salt Lake that provided a valuable source of income to ancient Larnaka. Lying 3 metres (10ft) below sea level, it is a true lake only in winter and early spring. The salt was once collected annually at the end of July, after the lake dried up, but today pollution has rendered it unfit for human consumption. From November to February migratory flamingos gather here, although their numbers are declining.

The Hala Sultan Tekke 6 [map] (daily mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–5pm; free but donation appreciated), seems mirage-like in summer, thrusting its minaret through greenery and palm trees beyond the blinding salt flats. This shrine contains the remains of the Prophet Mohammed’s wet nurse, Umm Haram (‘Sacred Mother’), known as Hala Sultan in Turkish, and is Cyprus’ most important place of Muslim pilgrimage. According to tradition, Umm Haram came to Cyprus with Arab invaders in 649. She fell from her mule near the Salt Lake, broke her neck and was buried here. The present-day mosque around the tomb dates from 1816.

The outer room has brightly painted octagonal columns and a women’s gallery to the right. In the inner sanctuary, the guardian (who also acts as a guide) will point out the trilithon structure above Umm Haram’s grave: two enormous stones about 4.5 metres (15ft) high, covered with a meteorite said to have come from Mt Sinai and to have hovered in the air here by itself for centuries.

Some 8km (5 miles) further is the village of Kiti and its church of Panagia Angeloktisti 7 [map] (Our Lady ‘Built by Angels’; winter Mon–Sat 7am–4.45pm, Sun 9.30am–4.45pm, summer until 6.45pm; free; photography allowed without flash). Constructed in honey-toned stone, the domed 11th-century edifice replaces a much earlier structure. Its outstanding feature is a splendid 5th- or 6th-century Byzantine mosaic in the apse, among the finest works of Byzantine art in Cyprus. A standing Virgin holds the Christ Child, flanked by the archangels Michael and Gabriel.

Red villages

The southeast corner of Cyprus is not only a major resort area, but the island’s vegetable garden. Potatoes, aubergines, tomatoes, cucumbers and onions are all grown for export in the fertile red soil of the Kokkinochoria (Red Villages) district.

The church at the mountain-top monastery of Stavrovouni

Shutterstock

Stavrovouni, Lefkara and Choirokoitia

The famous mountain-top monastery of Stavrovouni 8 [map] (Mountain of the Cross; daily Apr–Aug 8am–noon and 3–6pm, Sept–Mar 8–noon and 2–5pm; free but donation appreciated; men only) is located just off the A1 Limassol–Nicosia motorway. At an altitude of 750 metres (2,460ft), it has superb views north to Nicosia and the hazy Pentadaktylos Mountains, and south to the Salt Lake, Larnaka and the sea.

Stavrovouni was built on the site of a shrine to Aphrodite, which, like the monastery today, was off-limits to women. Nevertheless, Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, is said to have ventured up here in AD 327 to found the monastery and endow it with a piece of the True Cross. The relic is still proudly displayed in the monastery church. Note that cameras or videos are forbidden anywhere in the grounds. It is really not a place for casual tourism, and there is nothing extraordinary to see other than the view; the handful of monks follow the strictest regimen on the island, based on that of Mt Athos in Greece.

At the foot of the winding road up to Stavrovouni is Agia Varvara (Ayía Varvára) monastery (daily 8am–12pm and 3pm–6pm). Most of the local monks live here, as conditions up on the exposed summit are harsh, with only a half-dozen brothers resident there at any one time. Adjacent was formerly the studio of Brother Kallinikos (1920–2011), regarded (controversially in some quarters) as one of the best icon painters of his age.

Lefkara 9 [map], 40km (25 miles) west of Larnaka, is actually two villages, Pano Lefkara and Kato Lefkara, nestled in the foothills of the Troödos Mountains. Lefkara is synonymous with lefkarítika, the traditional embroidery that has brought the village fame for more than five centuries. Widely but incorrectly termed ‘lacework’, lefkarítika is actually linen openwork, stitched with intricate geometric patterns. Furthermore, quite a lot of what’s peddled here is imported and machine-produced – beware. The village is equally renowned for its silver-smithing, and hallmarked silver jewellery may be a more reliable and better-value purchase.

Some women still work in the narrow streets and courtyards of Pano (Upper) Lefkara, patiently turning out embroidered articles which you can buy from them or in one of the many shops. There are more sales outlets than strictly necessary, and as a result hustling, albeit of a mild kind, is common practice.

Lefkara is famous for intricate lefkarítika embroidery

Shutterstock

Smaller and mostly overlooked is Kato (Lower) Lefkara, an attractive village, with many of its traditional houses recently restored and window and door frames painted in bright Mediterranean blue. In a field to one side stands the 12th-century church of Archangelos (always open), with damaged but still intriguing frescoes dating from the 12th–15th centuries.

Archaeologically inclined visitors should head south to Choirokoitia (Khirokitiá), the modern village adjacent to the Choirokoitia Neolithic Settlement ) [map] (daily mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–5pm, mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7.30pm). Among the oldest sites in Cyprus, it dates to just after 7000 BC. The most interesting of the four areas is the main street, with its foundations of beehive-shaped houses called tholoi. Artefacts discovered here are on show at Nicosia’s Cyprus Museum (for more information, click here).

On the beach at Agia Napa

iStock

East to Agia Napa

Just beyond the resort hotels northeast of Larnaka, both A3 motorway and surface roads pass through the Dhekelia British Sovereign Base Area. You emerge back into Greek-Cypriot territory on the east at Xylofagou. Seaward of this is Potamos Liopetriou ! [map], a picturesque inlet jammed with small, gaily painted fishing boats, flanked by a couple of popular seafood tavernas. The local community is hoping to completely refurbish the area by 2020.

Following the Turkish occupation of Famagusta, Agia Napa @ [map] (Ayía Nápa) was transformed from a tiny fishing village into Cyprus’ major resort. Indeed, in recent years it has become one of the Mediterranean’s most notorious clubbing destinations. The change is most pronounced in the square around the monastery of Agia Napa (Our Lady of the Forest; winter 9am–3pm, summer 9am–9pm). The only forest here, really, is furnished by two 600-year-old giant sycamore figs in the monastery grounds.

However, during the day (when the clubbers are asleep or at the beach), the town centre is often peaceful. The monastery, built around 1500, remains one of Cyprus’ most handsome Venetian buildings, with an octagonal marble fountain in the Gothic cloister. It is now a conference centre for the World Council of Churches, and its church is open regularly for Sunday services.

Agia Napa’s growth is largely a result of its fine beaches of golden sand. The most famous one, 2km (1.2 miles) west of the centre, is Nissi, a picture-postcard strip and cove with limpid blue waters and a tiny island within paddling distance. At nearby Makronisos, another popular beach, there are 19 rock tombs dating from the classical and Hellenistic periods. East of the little port stretches Kryo Nero, less scenic but equally sandy.

Varosha boat trip

An intriguing boat trip from Agia Napa goes as far as the marine border at Famagusta to view the decaying town of Varosha. Once a major resort, it has been left to rot since 1974, when it was declared UN territory (though it is policed by the Turkish army). Now that travel to the North has been eased, you can also drive around Varosha’s outskirts on the Famagusta side, but you still can’t enter or take pictures.

The ever-popular Konnos Bay

Shutterstock

Cape Gkreko

The coast road east towards Cape Gkreko £ [map], the island’s southeastern tip, offers spectacular rocky inlets, caves and bays providing an escape from the crowds.

Just outside Agia Napa, beside the Grecian Bay Hotel, the Thalassines Spilies (Sea Caves) are famous for a much-photographed sea arch and frequented by snorkellers and divers. A few kilometres further along the main road yawn the more spectacular Spilies sta Palatia (Palace Caves).

Further still is the Cape Gkreko viewpoint. You have to walk the last 500 metres/yds uphill, but it is well worth the effort. From an altitude of almost 100 metres (330ft), the clifftop view looking west is stupendous. Just to the east is Cape Gkreko itself. The point is occupied by military installations and radio transmitters, so is accordingly off-limits.

Heading north will bring you to Konnos Bay, one of the most picturesque sandy coves in Cyprus, with a water-sports franchise. On a quiet day, it can be heaven, though always very shallow. In midsummer, Agia Napa ‘booze cruises’ and their sound systems disturb the peace. There is also raised concern about the bay being a fire hazard, and there are now plans underway to enlarge the access to the beach and build a carpark.

The coast road continues north to the purpose-built resort of Protaras, dominating more tiny coves like Fig Tree Bay.

Limassol and the South Coast

Limassol $ [map] (Lemesos in Greek) is Cyprus’ good-time town, with many restaurants, enterprising prostitutes and lively nightlife venues. Fittingly, the city hosts the island’s most exuberant pre-Lenten Carnival. In addition, it boasts Cyprus’ busiest harbour and was formerly the focal point of much of the wine industry. Most accommodation is away from the centre in a strip of high-rise shoreline hotels extending 16km (10 miles) east.

Crusading English king Richard the Lionheart stopped off at Limassol in 1191, deposed the tyrannical Byzantine usurper Isaac Komnenos and then proceeded to sell Cyprus – first to the Knights Templar, subsequently to the Lusignans. The crusader Knights of St John made the environs of Limassol their headquarters in 1291, after which the town flourished for some centuries.

By the early 19th century, earthquakes and medieval raids by the Mamelukes and Genoese had reduced the city to an insignificant village. British development of the wine industry breathed new life into it and, since the 1974 partition, greater Limassol’s population has almost doubled to 185,000, second only to that of Nicosia.

A backstreet of Limassol, overlooked by the Cami Kebir minaret

iStock

The only surviving medieval monument is Limassol Castle A [map], an imposing, 13th- to 14th-century stone fortification near the old port. Today it houses the Cyprus Medieval Museum (Mon–Sat 9am–5pm, Sun 10am–1pm), the island’s best collection from these periods, with some well-preserved tombstones, bronze or brass tableware, and silver plates from the Lambousa Treasure showing events from the life of King David. The building itself, with its echoing vaults, air shafts and stairways, is equally interesting and has fine views from the battlements.

The area around the castle is particularly pleasant, with lush gardens and historic buildings. Immediately south and west lies the Lanitis Carob Mill restoration project, with a selection of restaurants and bistros, an exhibition space, plus a small free display on the carob milling industry. The narrow lanes on all sides used to be the Turkish-Cypriot commercial quarter. The Cami Kebir (Great Mosque) B [map], a few metres east, is still in use; there’s a working Turkish bath (hamam) nearby. Also in this interesting quarter, you will find artisans’ workshops where the speciality is copper and tin ware, plus a selection of art and ceramics galleries. The municipality is engaged in a lengthy repaving project of the district, using poor-quality materials and leaving gaping ditches – take care when strolling.

Exhibits at the Lemesos District Archaeological Museum

Alamy

From the castle, it’s a 10-minute walk along part-pedestrianised Agiou Andreou to the Municipal Folk Art Museum C [map] (Mon–Fri 8.30am–3pm). It provides a glimpse of rural Cypriot life through wood-carving, embroidery, jewellery and weaving; and while it does have over 500 exhibits, lighting and labelling are poor, and you must buy the guide booklet to get much out of the displays.

Further east, abutting the seafront promenade, are the Municipal Gardens, a pleasant place to rest for a while – take the kids, there is a playground area – and the venue for the annual late-summer wine festival. At the far end of the gardens, the small Lemesos District Archaeological Museum D [map] (Mon–Fri 8am–4pm) is – as so often in Cyprus – strongest on Archaic, Geometric and Bronze Age artefacts, in particular a rhyton in the form of a bull and small fertility idols with upraised arms, clasping their breasts or holding sacred mirrors of Aphrodite/Astarte.

East of Limassol

Some 11km (7 miles) east of the town, between two clusters of beach hotels, are the ruins of ancient Amathus E [map] (daily mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7.30pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8am–5pm), one of the island’s oldest city-kingdoms. The ruins, dating back to 1100 BC, are centred on its agora (marketplace), and include basilicas, a temple of Aphrodite and an elaborate waterworks system.

About 16km (10 miles) further on by motorway or surface road is Governor’s Beach (Akti Kyvernitou) % [map], actually several coves of dark sand contrasting sharply with white-chalk cliffs just behind. There are a few tavernas and clusters of low-rise accommodation right behind. Farther east along the coast, you reach Zygi ^ [map], a former carob pod-loading port with a small marina and a cluster of seafood restaurants popular with Cypriots – though almost all the fare on offer is frozen or imported.

West of Limassol

Traces of one of the earliest phases of human presence on the island – hunters of pygmy hippos from 9000 BC – were found on the Akrotiri Peninsula west of Limassol. Nearly half of the peninsula is made up of salt marsh, frequented by migratory birds, notably pink flamingos, from October to March. On the east coast of the peninsula is hard-packed Lady’s Mile Beach, popular with Lemessans. Most of the peninsula is occupied by the airfield and other installations of the British Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area.

Just north of the peninsula, the impressive 15th-century Kolossi Castle & [map] (daily mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7.30pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–5pm) is one of the icons of Cypriot tourism. Once the headquarters of the Knights of St John, this is the base from where they administered their considerable sugar plantations and vineyards. The three-storey Commanderie, as the headquarters was known, gave its name to their prized Commandaria dessert wine, still produced today by commercial wineries.

Among the rooms, all now empty, a middle-storey one with a huge fireplace was the kitchen; in the adjacent room is a damaged fresco, the only surviving decoration. Climb the steep, narrow spiral staircase for the view from the battlements. Outside you can see traces of an ancient aqueduct and an imposing Gothic sugar refinery.

Kourion’s Roman theatre

Shutterstock

Before exploring the great archaeological site of Kourion, stop in nearby Episkopi village to do a little homework at the Kourion Archaeological Museum (Mon–Fri 8am–3.30pm), which holds dramatic finds from the earthquake that devastated Kourion in AD 365. On display is a touching group of three human skeletons: archaeologists believe them to be of a 25-year-old male protecting a 19-year-old female with an 18-month-old baby clutched to her breast. Other exhibits include a Roman stone lion fountain, terracotta vases and figurines.

Just west of Episkopi is Kourion * [map] itself (daily mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7.30pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–5pm). Along with Salamis in the north (for more information, click here), this is the island’s most important archaeological site, spectacularly set on a bluff above Episkopi Bay. Today, there’s a broad, popular beach with a few shack-like tavernas at the base of the palisade.

Experts attribute the foundation of the town to Mycenaean settlers during the 13th century BC. Known as Curium to the Romans, it converted to Christianity in the 4th century; after the Arab raids of the 7th century, the bishopric moved to Episkopi, leaving Kourion to sink into oblivion.

The remains of a public bathhouse

iStock

Your first stop should be the reconstructed Roman theatre (AD 50–175), spectacularly perched on the edge of the bluff. The theatre once seated 3,500 and is now used for early-summer performances of Shakespeare plays, and concerts. Behind the theatre is the 4th-century AD Annexe of Eustolios. The floor mosaics of birds and fish indicate that Eustolios was a man of wealth and taste; a long inscription to Christ suggests that he was also a Christian convert. Eustolios later added an adjacent bathhouse, which he opened to destitute survivors of the earthquake, as attested by another inscription. Its central room features some more remarkable mosaics, including one of Ktisis, the female spirit of creation, wielding a Roman foot-ruler.

The extensive ruins of the city centre, 300m/yards northwest along a graded path, include the agora (marketplace) with its nymphaeum (fountain house). Turn to the left to explore the remains of an early Christian basilica. The basilica’s plan reveals 12 pairs of granite columns, recycled ancient masonry, for the nave. To the north is the baptistry, where new converts disrobed and were anointed with oil before descending to the cross-shaped font.

On the other side of the walkway is the House of the Gladiators, so named for its mosaics of two duels, one with an aristocratic-looking referee – perhaps the owner of the house. Nearby, also under a protective canopy, is the Achilles mosaic. It depicts Achilles, disguised as a woman to avoid enlistment in the expedition to Troy, being tricked by Odysseus into grabbing a spear and shield and revealing his identity.

House of the Gladiators, Kourion

iStock

The Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates/Ylatis ( [map] (daily, same hours as Kourion; separate charge) lies 3km (2 miles) to the west. Apollo was worshipped here as god of the woodlands as early as the 8th century BC, but most of the present structures were put up around AD 100 and destroyed in the earthquake of 365.

From the ticket booth, take the path west to the pilgrims’ entrance (through the remains of the Pafos Gate). The buildings here were probably hostels and storehouses for worshippers’ votive offerings. The surplus was carefully placed in the vothros pit (at the centre of the site), which was full of terracotta figurines, mostly horse riders – still intact when uncovered by the archaeologists. Follow the sanctuary’s main street to the Temple of Apollo, which has been partially reconstructed to look as it did in AD 100.

Petra tou Romiou, where Aphrodite first emerged from the sea

Shutterstock

West to Petra tou Romiou

If the flat, hard-packed sands of Kourion Beach don’t appeal to you, try the looser, coarse sand-and-shingle of Avdimou (Evdhímou) Beach, about 10km (6 miles) further west, with two tavernas. But if you crave the creature comforts of a resort, then continue on to Pissouri , [map]. The latter is an attractive, sheltered place, with a coarse but fairly long sand-and-shingle beach, plus ample accommodation and eating opportunities just behind.

West of Pissouri, just beyond the border into Pafos district, a huge sea-washed monolith juxtaposed with white cliffs behind is the famous Petra tou Romiou ⁄ [map]. This is named for legendary Byzantine hero Digenis Akritas, aka Romios, who used the big rock (pétra in Greek) plus smaller ones around it as missiles against Arab seaborne raiders. Opposite the rocks, along the B6 road, a parking area gets very crowded at sunset. The beach here is mostly coarse gravel, and the water is often storm-stirred.

Goddess’ birthplace

Petra tou Romiou has long inspired legends, as before Digenis Akritas’ time it was reputed to be the birthplace of Aphrodite, who emerged from the sea here (though Kythera Island in Greece also strenuously claims this honour).

Typical village in the Troödos Mountains

Shutterstock

Troödos Mountains

The Troödos (Troödhos) Mountains in central Cyprus are the island’s principal upland – and pronounced, approximately, ‘troh-dhos’ rather than ‘true-dos’ as many foreigners are apt to say. They provide many things: a breath of fresh air for hot and flustered visitors and locals, a splendid collection of tiny Byzantine churches scattered around the hillsides, wonderful walking trails and, most importantly, much of the island’s fresh water.

Roads up the mountain climb through foothills with rushing streams and orchards, past villages perched on the slopes, surrounded at higher altitudes by pine forest. Historically, monks and Greek-Cypriot EOKA fighters found refuge here; more recently the monasteries have been joined by resort hotels, with even a little winter skiing near the resort of Troödos. On the southern slopes in Limassol district, up to the 1,000-metre (3,300ft) contour, are the vineyards and villages that produce most of Cyprus’ wine.

Platres to Troödos

At an altitude of 1,200 metres (3,900ft), Pano Platres ¤ [map] makes a good base for visiting the entire Troödos region. This little ‘hill station’ occupies a charming and shady mountain site and comprises several hotels, large numbers of private villas, restaurants and shops. The main pastime here is walking, and the Cyprus Tourism Organisation has marked several nearby mountain trails, aimed at most ability levels – get details at the Platres tourist office. The most popular hike is the 2km (1.2-mile) one up to the pretty Kaledonia Falls. The walk starts at the Psilodendhro restaurant and trout farm just outside Platres, and is well marked.

Omodos (Ómodhos) ‹ [map], renovated as a showpiece wine-producing village, lies 8km (5 miles) southwest of Platres. It’s an attractive place, but has become over-commercialised, and the tour buses diminish the atmosphere their occupants have come to savour. However, you can still find calm in the village’s monastery of Timios Stavros (True Cross), which dominates the broad, cobbled square in front of it – probably an example of Lusignan urban planning.

All roads in the mountains seem to lead to the eponymous resort of Troödos › [map], which at 1,676 metres (5,500ft) is the island’s highest facility. There are ski slopes nearby, while in spring and autumn it’s a good starting point for dedicated ramblers. Avoid midsummer, when its single main street turns into an overcrowded promenade of kitsch stalls and rumbling tour buses. Just off this ‘high street’, a visitor centre (Mon–Fri Sept–June 10am–3pm, July–Aug 10am–4pm; Sat June–Aug 10am–4pm; Sun Apr–May and Sept–Oct 10am–3pm, June–Aug 10am–4pm) helps orientate visitors to the high mountains, and provides maps and information on the local wildlife and plants.

Mt Olympos (1,952 metres/6,404ft), Cyprus’ tallest peak, also known locally as Chionistra (Khionístra, ‘Snow-Tipped’), is best visited by car up a narrow road. For security reasons, you have to walk the final distance up to the giant British radar ‘golf ball’ and Cypriot installations on the double-humped summit, and the views are surprisingly limited. It’s preferable to tackle one of two nature trails – the Atalante or the Artemis – that circle the peak.

Old Kakopetria

Shutterstock

Kakopetria and Galata

Kakopetria fi [map], chief village of the Solea region north of the Troödos ridgeline, is easily reach by fast roads from Nicosia, and is accordingly popular at weekends and holidays. The highlight of the place is its ridgeline old quarter, a protected ensemble that’s now home to recommendable eating and accommodation. This historic part of town is essentially one long, narrow street running parallel to the leafy river. Its houses with their river-view balconies have been restored to bring out the subtle russet, amber and silver hues of the local stone.

Frescoed Churches

The Troödos Mountains’ remarkable painted churches were built between the 11th and the 16th centuries. For visitors, their astonishing degree of preservation and the beauty of their artwork makes for compulsive viewing. For scholars, the churches provide a fascinating lesson in provincial Byzantine and post-Byzantine art; there is nothing else like them in the Mediterranean other than the country churches of Crete and Rhodes. The original function of the frescoes was as religious cartoon strips, teaching the simple, illiterate and often isolated parishioners the lessons of the Gospels; today they serve as a fascinating document of Lusignan and Venetian life, as the painters – mostly anonymous – interpreted Biblical episodes with contemporary medieval personalities and dress. Most of the churches have been listed on Unesco’s World Cultural Heritage register.

The densest concentration of painted churches lies on the north slopes Troödos, where Panagia Asinou (for more information, click here), Agios Nikolaos tis Stegis (in Kakopetria), Panagia tis Podithou (in Galata), Agios Ioannis Lambadistis (in Kalopanagiotis) and Panagia tou Araka (near Lagoudera) are all within a short drive of each other. Some have set visiting hours; in other cases you will have to contact the key-holder, either a priest or lay person, who lives nearby. Mobile phone numbers are usually posted on the church door. Photography, certainly with flash or tripod, is rarely if ever allowed.

Just outside the village is one of the Troödos Mountains’ most famous frescoed churches, Agios Nikolaos tis Stegis (St Nicholas of the Roof; Tue–Sat 9am–4pm, Sun 11am–4pm; free but donation appreciated). The name refers to the upper roof of shingles, built in the 15th century to shelter the older domed roof of tiles. Inside, the oldest frescoes date from the church’s foundation in the 11th century, but the most unusual ones – including the Virgin nursing the infant Jesus, and the Angel at the Tomb – are from some centuries later.

Just north of Kakopetria, Galata fl [map] has another Unesco-listed church of 1502, Panagia tis Podithou; the key-keeper can be contacted at the café in the village square (you can usually find the number at the front). Although its very Italianate fresco decoration was never completed, what exists – including an extravagantly secular Crucifixion over the west door, Solomon and David flanking the Communion of the Apostles in the apse – justifies the trouble of gaining admission. The same key-keeper will then escort you to Archangelos (aka Panagia Theotokou) nearby, dating from 1514 and containing an unusually complete cycle portraying the life of Christ.

The frescoed ceiling of Panagia tou Araka

Shutterstock

Marathassa

Easily reached either from Troödos resort or from Kakopetria, the Marathassa valley west of Solea is home to more mountain villages and painted churches. From either start point, the first village reached is Pedoulas ‡ [map], famous for its cherries – and its church of Archangelos Michail (daily 10am–6pm; free but donations welcome), built in 1474. Vivid frescoes, cleaned during the 1980s, include The Sacrifice of Abraham, and a Baptism complete with fish in the River Jordan. In Moutoullas village, 3km (2 miles) downhill, you’ll find the earliest of the frescoed churches, Panagia tou Moutoulla, built in about 1280 (call tel: 22 952 677 or 97 733 480 to arrange a visit). The frescoes, while not the most expressive hereabouts, are unretouched and idiosyncratic. If time is short, prioritise attractive Kalopanagiotis ° [map] (Kalopanayiótis) village, 1km (0.5 miles) further along, whose star is the intact riverside monastery of Agios Ioannis Lambadistis (winter Mon–Sat 9am–1pm and 2–4pm, Sun 10am–4pm, mid-April to mid-Sept Mon–Sat 9am–1pm and 2–6pm, Sun 10am–6pm; free). The main church is actually triple, with different fresco cycles completed at various times between the 13th and 15th centuries; most of them have been carefully restored since 2009 by students of London’s Courtauld Institute of Art. The northernmost, Latin chapel, with the most complete Italo-Byzantine sequence on the island, was clearly painted by a local artist who had spent extensive time in Italy. In one wing of the monastery buildings is a rewarding gallery of Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons.

West to Kykkou

The main roads west from either Pedoulas or Kalopanagiotis lead quickly to the gem that is the monastery of Panagia tis Kykkou · [map] (pronounced Tchýkou in dialect: daily June–Oct 10am–6pm, Nov–May 10am–4pm; free but charge for museum), proudly remote from the world on a mountainside surrounded by pine forest.

Kykkou is the richest and most important monastery on the island. Founded in 1094 by a hermit, it grew in prestige when Emperor Alexis Komnenos (ruled 1081–1118) gave it a rich land grant and an icon of the Virgin supposedly painted by St Luke, but now covered in gilded silver. Its legendary rain-making powers still bring in farmers to pray in times of drought.

But apart from the precious icon and a few other pieces, there is little of historical value here, since the monastery was gutted by fire four times between 1365 and 1813. Frankly garish mosaics and frescoes lining every vertical surface are workmanlike at best. Kykkou is primarily a place of pilgrimage and a preferred venue for baptisms, when proud relatives cheerfully ignore the ban on photography and videoing enforced against the heterodox, who can occasionally be met with faint hostility. In the quieter museum you can learn about Kykkou’s history and see some of its finest treasures.

Kykkou is also famous for having had Archbishop Makarios among its novices (he is buried on a hill above the monastery). During the 1950s, Kykkou served as a communications and supply base for EOKA, and thus became a symbol of the Cypriot nationalist struggle.

West of Kykkou, onward roads lead downhill into the Cedar Valley (Koilada tou Kedron) º [map], one of the signal successes of the island’s reforestation programme. This steep-sided ravine hosts thousands of indigenous cedar trees (Cedrus brevifolia), first cousins to the more famous cedars of Lebanon. Nearby, around Tripylos peak, is a small reserve dedicated to the protection of the indigenous, formerly endangered Cypriot wild mountain sheep, the moufflon.

Eastern Troödos churches

If you’ve developed a taste for frescoed churches, there are several more in the eastern half of the Troödos, easily accessible from Platres or Kakopetria. The most spectacular of these, just north of Lagoudera ¡ [map] (Lagoudherá) village, is Panagia tou Araka (Our Lady of the Wild Vetch), with most frescoes dating from 1192. The more unusual include a fine dome Pandokrator (Christ in Majesty), the only one in the Troödos, and adjacent, finely observed Presentations of Christ and the Virgin near the apse.

In Pelendri (Peléndhri) ™ [map], 14th-century Stavros at the village outskirts (key-keeper lives adjacent) features scenes from the life of the Virgin. Much closer to Limassol, Louvaras village # [map] can offer deceptively tiny Agios Mamas church, crammed full of well-preserved frescoes from 1495 by Philip Goul, one of the few identified local painters.

Off the eastern edge of the Troödos, at Palaichori ¢ [map], you’ll find another member of the roster of Unesco mountain churches, Metamorfosis tou Sotiros (Transfiguration of the Saviour), dating from the 15th and 16th centuries and containing (predictably) a fine representation of the Transfiguration.

Unloading the catch of the day in Pafos harbour

Shutterstock

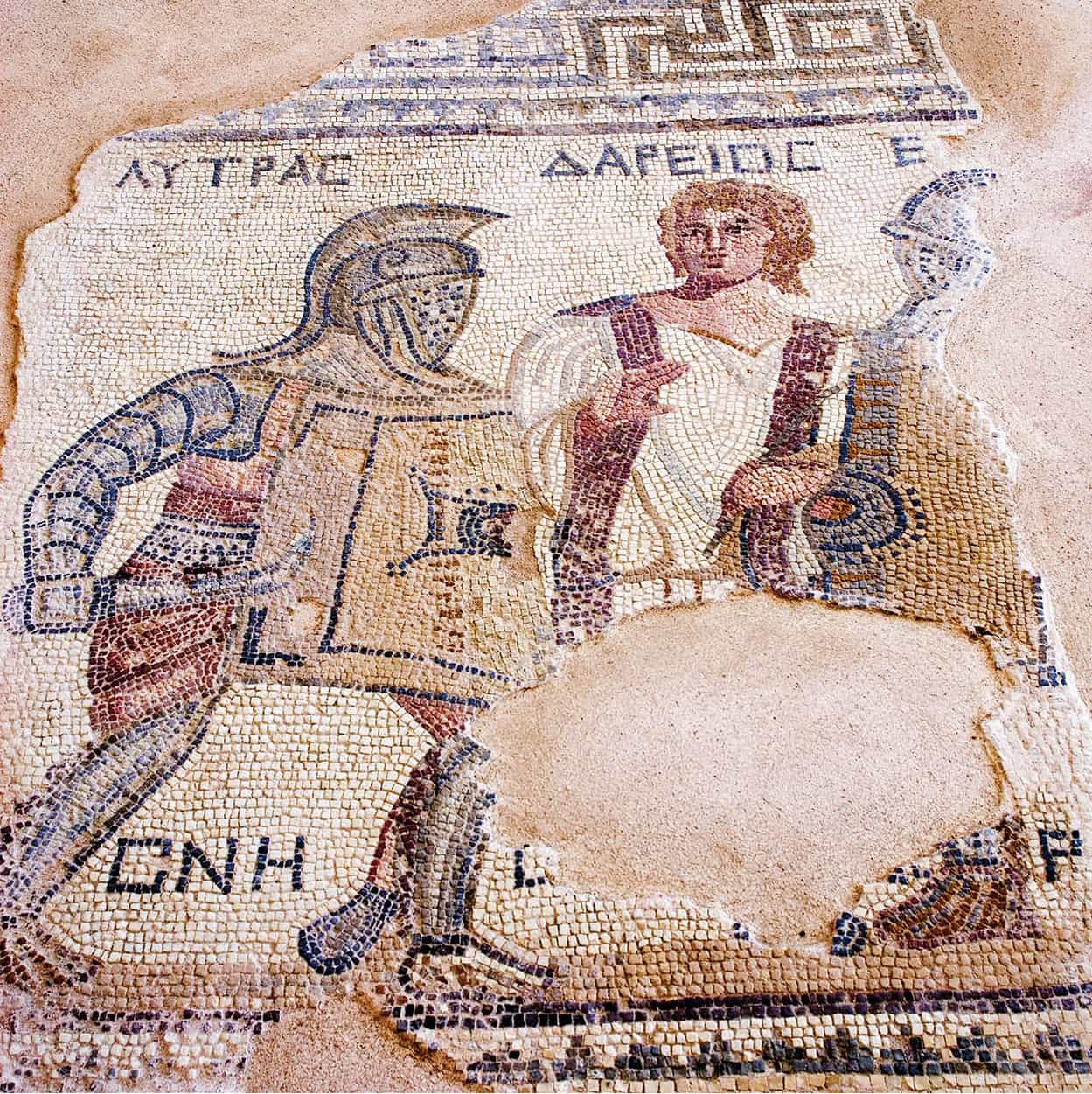

Pafos and the West

Once a sleepy fishing port, Pafos (Páphos) ∞ [map] has been transformed into a booming resort town. But visitors who want more than just sun and sand have plenty to occupy them. Ancient Nea Paphos was Cyprus’ Roman capital and has a wealth of historic sites. It is also a good base for exploring nearby hill-villages and the rugged Akamas Peninsula.

Legend attributes the founding of nearby Palaia (Old) Paphos to the priest-king Kinyras, and that city-kingdom gained renown as the centre of Aphrodite’s cult. The last king of Palaia Paphos, Nikokles, established the port of Nea (New) Paphos during the 4th century BC, though Palaia Paphos remained the centre of Aphrodite worship until the 4th century AD. Within 100 years of its founding, Nea Paphos surpassed Salamis as the chief city of Cyprus. However, earthquakes in 332 and 342 and the Arab attacks of the 7th century forced most of the population inland to Ktima. Medieval Pafos languished as a miserable, unsanitary seaport; however, under the British the population gradually rose from about 2,000 to about 9,000 in 1960. It continued to grow and prosper, with the opening of Pafos International Airport in 1985 firmly establishing it as a resort, and later as a major second- (or first-) home venue for foreigners.

Heavily developed Kato (Lower) Pafos, along the seaside, is where most visitors stay. The harbour still provides a picturesque haven for fishing and excursion boats as it curves around a jetty to the Medieval Fort A [map] (daily mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7.30pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–5pm), all that remains of a much larger Lusignan castle. The Ottomans used it as a prison, the British as a salt warehouse; it is currently empty, with only the rooftop views justifying the admission fee.

Ancient ruins in Pafos

Shutterstock

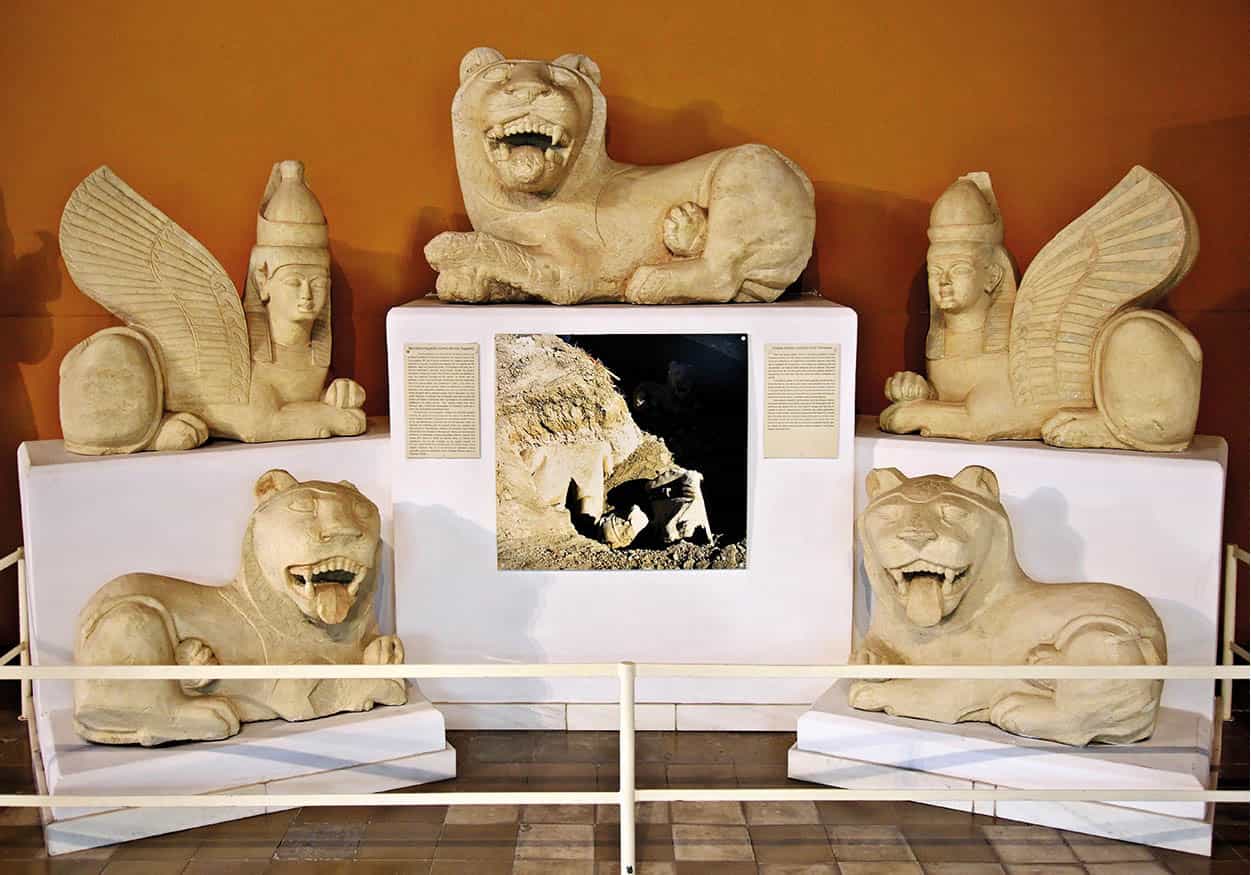

With the harbour on your left, walk towards the large, modern shed-like building in the distance. Beyond this lie the famous Paphos Mosaics B [map] (daily mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7.30pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–5pm). These splendid decorative floors were uncovered in the remains of luxurious Roman villas of the 2nd to the 5th centuries AD. The ‘houses’ are named after the mosaics’ most prominent motifs. The House of Dionysos displays the god of wine riding a chariot drawn by two panthers, flanked by satyrs and slaves. This and other scenes, such as Dionysos offering a bunch of grapes to the nymph Akme, and Ikarios of Athens getting shepherds drunk with their first taste of wine, were customary decorations for banqueting halls. The House of Aion has a spectacular five-panelled mosaic, whose central panel depicts Aion, god of eternity, judging a beauty contest between a smug-looking Queen Cassiopeia (the winner) and unhappy, prettier water nymphs departing on assorted sea-monsters. The single other villa open to the public, the House of Theseus, features the first bath of the infant Achilles.

Pafos is famed for its Roman mosaics

Shutterstock

A short walk north leads to the restored Odeion C [map], a small theatre dating from the 2nd century AD, built entirely of hewn limestone blocks. In a picturesque hillside setting, it seats 1,250 spectators for musical and theatrical performances held occasionally in the summer. Excavations continue in the adjacent agora, by a team from the Jagiellonian University of Krakow. So far about 5 percent of the agora has been excavated, leaving lots to uncover.

Kato Pafos to Ktima

From the harbourside car parks and public bus terminal, first Apostolou Pavlou, and then Stassandrou, climb towards the remains of 4th-century AD Agia Kyriaki basilica D [map]. Amid the ruins of the seven-aisled church, you can make out mosaic pavements with floral and geometric patterns and columns of green-and-white marble imported from Greece. Arabic graffiti on the columns dates from the invasion that destroyed the basilica in 653. One of the columns is called St Paul’s Pillar, to which the apostle was (apocryphally) tied and lashed 39 times for preaching the Gospel. Amid the ruins is handsome post-Byzantine Panagia Chrysopolitissa church, sometimes also referred to as Agia Kyriaki.

A little further along Apostolou Pavlou is the intriguing sight of a tree festooned with hundreds of handkerchiefs and rags. It marks the Catacomb of Agia Solomoni, once regarded as a spot where prayers could be miraculously answered, and still doing a good trade with believers today. The tradition of tying a handkerchief or rag as a votive offering to a tree or bush at a sacred site is common in the Middle East. Just north of here, hacked out of the living rock on Fabrica hill, is the Australian-excavated Hellenistic theatre E [map], one of the largest on Cyprus.

Still further northwest is ancient Nea Paphos’ necropolis, the so-called Tombs of the Kings F [map] (daily mid-Apr–mid-Sept 8.30am–7.30pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–5pm). The title is a misnomer, as the subterranean burial chambers hacked out of the soft rock here between the 3rd century BC and the 3rd century AD were meant for the local privileged class, not kings. The tomb architecture is based on Ptolemaic adaptations of Macedonian prototypes: spacious courtyards with Doric columns and decorative entablatures. Of the eight tomb complexes, numbers 3, 4 and 8 are the best.

Ktima

Set on a blufftop above the resort, the upper part of Pafos, known as Ktima, is a normal Cypriot provincial town compared to the coastal strip. After shopping at the colourful daily produce market and a variety of souvenir stalls, you can sit down for a drink or a meal in the narrow lanes of the old centre.

There are two small museums in the centre of Ktima. The Ethnographical Museum of Pafos G [map] (local English spelling; also known as the Eliades Collection; Exo Vrysis 1; www.ethnographicalmuseum.com; Mon–Sat 10am–5pm, in summer until 6pm, Sun 10am–2pm), opened in 1958, occupies a charming 19th-century house. It combines priceless antiques, a mocked-up rural room, basketry, old wagons and – in the garden – a genuine, 3rd-century BC rock tomb. Nearby, in a wing of the Bishop’s Palace, the Byzantine Museum (Mon–Fri 9am–3pm, Sat 9am–1pm) displays icons salvaged from local chapels, including the oldest known on the island, an 8th- or 9th-century icon of St Marina.

The remoter Archaeological Museum of the Pafos District H [map] (Mon–Fri 8am–4pm, Sat 9am–4pm, Sun 10am–1pm), on the road to Limassol, houses some remarkable sculptures found in the House of Theseus (for more information, click here), including a statue of Asklepios (the Greek master of medicine) feeding an egg to the snake coiled around his staff. Also, look out for the Hellenistic clay hot-water bottles, specially moulded to fit all parts of the body.

Remains of fluted columns at the Sanctuary of Aphrodite

Shutterstock

Southeast of Pafos

Just southeast of Pafos is the village of Geroskipou (Yeroskípou) § [map], whose name derives from Hieros Kipos, meaning ‘Sacred Garden’; pilgrims would stop here on their way to Aphrodite’s temple at Palaia Paphos. The 9th-century church of Agia Paraskevi (Mon–Sat 8.30am–1pm and 2–4.30pm; free) in the centre of Geroskipou is a rare island example of a six-domed basilica. Inside are fine, if damaged, 15th-century murals and a much-revered icon from the same period, with a Virgin and Child on one side and a Crucifixion on the reverse.

In a restored house nearby is a Folk Art Museum (mid-Apr–mid-Sept 9.30am–5pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr 8.30am–4pm). Typical of a rich Cypriot’s dwelling in the late 18th or early 19th century, the upper storey is ringed with handsome wooden balconies. Display rooms are thematic, devoted to crafts such as carding and ginning cotton, spinning and weaving, tinning vessels, and a reproduced cobbler’s workshop.

From here, continue southeast along the B6 for about 12km (8 miles) to Kouklia ¶ [map], once Palaia Paphos (Palaipaphos), where the cult of Aphrodite was celebrated. The rites of the love goddess flourished at the Sanctuary of Aphrodite (mid-Apr–mid-Sept daily 8.30am–7.30pm, mid-Sept–mid-Apr daily 8.30am–5pm). Most of the valuable finds have been taken to Nicosia, though after much bureaucratic wrangling the original of the famous 2nd- or 3rd-century AD mosaic of Leda and the Swan has been returned. It has pride of place in the Palaipaphos Museum (same hours as the Sanctuary; same ticket), inside the sturdy Château de Covocle (originally a Lusignan manor-farm). The museum galleries are upstairs from a 13th-century vaulted banquet hall, the acoustically superb venue for early summer chamber music concerts. Those with their own transport may want to continue inland to the so-called Palaia Enkleistra (key and instructions from museum staff in exchange for piece of ID), a 15th-century cave-hermitage with damaged but unique frescoes; on the ceiling, dating from the era when the Western and Orthodox churches were briefly united, is a rare depiction of the Holy Trinity.

The monastery of Agios Neofytos

Alamy

North of Pafos

Beaches in Pafos are unremarkable, so many visitors travel 10km (6 miles) north to better sands at Coral Bay (Kolpos Koralion). Further up the coast, there are more beaches either side of Agios Georgios (Áyios Yeóryios), which has accommodation, restaurants and the remains of a basilica with mosaic flooring (free access). Beyond pebbly ‘White River Beach’ just north of Agios Georgios, you’ll pass sandier Toxeftra beach, and the turning inland to the famous Avgas Gorge, a favourite destination for hikers, with plenty of wildlife-spotting opportunities. Beyond here, it’s best to have a 4WD vehicle as you head up to Cape Lara and the vast sandy beaches on either side. The northerly, dune-clad Lara Bay • [map] is an official marine reserve, set aside to protect the endangered green and loggerhead turtles that come ashore on summer nights to hatch and bury their eggs.

Some 9km (5 miles) northeast of Pafos, the monastery of Agios Neophytos ª [map] (Áyios Neóphytos; daily Apr–Oct 9am–1pm and 2–6pm, Nov–Mar 9am–4pm; charge for Hermitage) dominates a wooded slope. Its church has fine 16th-century frescoes and icons, but the main focus is the 12th-century Enkleistra (Hermitage), around which the monastery grew. The saintly historian and theologian Neophytos (1134–1219) supposedly hacked this cave-dwelling out of the rock with his own hands and then supervised the creation of the frescoes that decorate the chapel and cell. One shows Neophytos himself, being escorted into Paradise by two archangels.

On the north coast 35km (22 miles) from Pafos, the small town of Polis q [map] stands where the ancient citykingdom of Marion once thrived from nearby gold and copper mines. Archaeological finds from the site are on display at the Marion-Arsinoe Archaeological Museum (Mon–Fri 8am–4pm, Sat 9am–3pm). The old town centre has been restored and has a pleasant if touristy cluster of cafés and restaurants. Polis is a prelude to the fishing port and beach resort of Lakki (Latchí) w [map], where seafood tavernas cluster around the fishing port; to either side are decent sand-and-pebble beaches.

Romantics should head west to the end of the paved road, from where it’s a brief stroll to the Baths of Aphrodite e [map], a small, shaded natural pool and springs set in a cool green glade, where the goddess was wont to bathe. Meatier hikes – either a coastal track giving swimming opportunities, or more challenging proper trails uphill – lead from here further into the Akamas Peninsula, one of the few unspoilt wildernesses left on the island and long a battleground between environmentalists and developers (see box).

A Wilderness Under Threat

Untamed and scenic, the last major piece of unspoilt coastline in South Cyprus, the Akamas Peninsula arouses strong passions, among conservationists, hikers and wildlife-spotters on the one hand, and tourist-enterprise developers, the Orthodox Church and local villagers on the other. Since 1986, organisations as disparate as the World Bank, the European Union, Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace have called for the creation of a local national park. Matters are complicated by the entire peninsula being a patchwork of private land (Greek- and Turkish-Cypriot owned), state forest, village commons and Church holdings. The British Army, who long used the peninsula as a firing range, departed in 1999 after sustained environmentalist protest, but ironically their presence had a preservationist effect. Until stopped from doing so, the Church removed sand from west-coast beaches to fill traps at Tsada golf course. Hunters, out in force on Wednesdays and Sundays during winter, also agitate against any protection regime. Since the millennium, and in particular since 2005, government proposals have envisioned a reserve much reduced in size and strictness from original plans, and ‘controlled’ development. The major player in the latter is Carlsberg magnate Photos Photiades, whose extensive north-coast property he would like to turn into a luxury resort. Various schemes for compensation or land-swaps have been proposed to induce him (and other owners) to leave. However, with the sharp economic downturn and the drop in tourist numbers, such a resort (or payouts) seem increasingly unlikely. In 2016, the government designated all state-owned land in Akamas as a national forest park, however talks about ‘mild development’ are ongoing.

The rugged landscape of the Akamas Peninsula

iStock

Northeast along the coast from Polis, a scenic route leads through relatively undeveloped seafront villages and past secluded beaches near Pomos and Pachyammos (Pahýammos). Beyond the latter, the road snakes through the steep hills of Tillyria to avoid the Turkish military enclave of Kokkina (Erenköy), before reaching the Cypriot-patronised resort of Kato Pyrgos r [map], no longer the end of the line since a crossing point to the North opened nearby.

Northern Cyprus

The Turkish-occupied north, which comprises around 38 percent of the island, contains some of Cyprus’ most beautiful landscapes, best beaches, most dramatic monuments and two of its most historic towns. Partition and the subsequent political isolation long helped preserve the countryside from the ravages of mass tourism, but since 2000 development around Keryneia in particular has been every bit as intensive as anywhere in the South.

It is possible to whizz around Northern Cyprus in a day and cover – or at least glimpse – some of the main highlights, although unless you are short on time, this is not recommended. In three or four days you can see all the sights, including northern Nicosia (for more information, click here), at a more leisurely pace.

Visiting the North

There are seven crossing-points along the buffer zone that separates North and South. There are two crossings for pedestrians in central Nicosia: Lidras/Lokmacı in the Old City and at the former Ledra Palace Hotel close to the Pafos Gate. Border crossings for vehicles are at Agios Dometios/Metehan in the western suburbs of Nicosia; at Pyla/Pergamos (Beyarmudu), handiest for Karpasia; direct to Famagusta (Gazimağusa); at Astromeritis-Kato Zodeia (Boştancı), near Morfou (Güzelyurt); and Kato Pyrgos (Günebakan) on the north coast.

The procedure for crossing is easy, though at weekends, there can be long queues. Officially the border opens at 8am and closes for returning visitors at midnight, but the Nicosia crossings tend to be open almost around the clock. The Greek Cypriot police will view, but not stamp, your passport going in each direction; the Turkish Cypriot police will, upon request, give you a loose-leaf paper visa. They will stamp this paper visa, but make sure they do not stamp your passport, or you will be banned from re-entry to the South. There is no limit on the number of times you may cross. EU citizens have the right of unrestricted movement throughout Cyprus; there may be restrictions for non-EU citizens, especially coming from North to South.

Motorists going from South to North must buy supplemental insurance at the border, since no EU-contracted policies are valid in the Turkish Cypriot sector. The minimum term is 3 days, and the policies – with a low level of cover, and a record of not paying out compensation – are all but useless other than to wave at police. If you have an accident that immobilises you in the North, get the car moving again without involving the car-hire company in the South – don’t risk being stranded in the North.

The ruins of Agios Ilario offer stupendous views

Shutterstock

The Mountain Castles

North of Nicosia, the Mesaoria plain (Mesarya in Turkish) rises abruptly at the Keryneia Hills, which Lawrence Durrell, who lived in their shadow from 1953 to 1956, described as ‘par excellence the Gothic range, for it is studded with crusader castles pitched on the dizzy spines of the mountains, commanding the roads which run over the saddles between’. The range’s most striking peak is Pentadaktylos (Beşparmak, ‘Five Fingers’).

The three castles now lie in noble ruin, victims not of enemy bombardment but of partial demolition by the Venetians. Most extensive is Agios Ilarion t [map] (daily summer 9am–5pm, winter 9am–1pm and 2–4.45pm), which climbs along knife-edge ridges in three tiers of battlements and towers, reaching an altitude of 670 metres (2,200ft) under twin peaks, with steps leading up and down in all directions.

The castle was built in the 10th century around an earlier church and monastery honouring the hermit Hilarion, who fled here when the Arabs took Syria. The original Byzantine structure was fortified and extended by the Lusignans as a summer residence. The views down to Keryneia harbour are superb and, on a clear day, you can see the mountains of southern Turkey some 100km (60 miles) away.

Another dramatic, if small, ruinous castle is Buffavento y [map] (‘Buffeted by the Winds’; unrestricted access), just off the easterly major road over the Pentadaktylos. This is Cyprus’ highest fortress, at 940 metres (2,991ft), with views over literally half the island, especially towards dusk when there’s the spectacle of Nicosia turning on its lights.

Offering the most beautiful sheltered harbour in Cyprus and a grand old castle, the charming town of Keryneia u [map] – Girne in Turkish, still Kyrenia to most Greek Cypriots and expats – is the most strikingly situated on the island. The venerable buildings that line the port have almost all been converted into bars or restaurants of indifferent quality, but the setting is so irresistible that most every visitor patronises them at least once.

Bellapais Abbey

Shutterstock

Overlooking the harbour is massive Keryneia Castle (daily summer 9am–7pm, winter 9am–3.30pm), whose fortifications date mostly from the Venetian era. Today, its walls enclose a Byzantine chapel, royal apartments and various historical displays, including the Kyrenia ship, the oldest wreck ever recovered from the seabed (and featured on three Cypriot euro coins). This Greek trading ship sank in 30 metres (100ft) of water just offshore around 300 BC and was discovered in 1967 by a Greek-Cypriot diver. The surviving hull has been painstakingly preserved and remounted, and is shown with part of its final cargo.

In the foothills behind Keryneia are the substantial ruins of the superbly sited Gothic abbey of Bellapais i [map] (Beylerbeyi; daily summer 9am–7pm, winter 9am–3.30pm). Facing the sea, the ‘Abbaye de la Paix’ (of which the current name is a corruption) stands on a 30-metre (100ft)-high escarpment, its buildings enveloped in cypresses, palms and citrus trees. The abbey was built by Premonstratensian (Norbertine) brothers generously funded by Lusignan kings, and took on its present form during the 13th and 14th centuries. The elegant cloister is adorned with finely carved figures, while the splendid vaulted refectory has six bays and a fine rose window; underneath the refectory is a fine undercroft with ‘palm’ vaulting upholding the ceiling.

West of Keryneia

You can follow the line of the Pentadaktylos range west to their end, and continue on through the main Maronite Catholic village of Kormakitis (Koruçam), enjoying something of a revival since 2003, with property being confidently renovated. Southward around the curve of Morfou Bay is the old bishop’s seat of Morfou o [map] (Mórphou/Güzelyurt) and its venerable monastery of Agios Mamas (daily, usually open from 9am, closing times vary seasonally), one of the few churches in the North still used (on feast days) for Orthodox worship, thanks to the efforts of the charismatic Bishop of Morfou, Neophytos.

On the narrow strip of Northern Cyprus squeezed between the buffer zone and the sea lie the remains of the 6th-century BC Graeco-Roman town of Soloi p [map] (Soli; daily, usually open from 9am, closing times vary seasonally) and those of the Persian-era (5th-century BC) palace at Vouni (Vuni; daily, usually open from 9am, closing times vary seasonally). Soloi is known for its fine mosaics, difficult to see except on bright days owing to a huge protective canopy.

Othello’s Tower, Famagusta

Shutterstock

Famagusta (Gazimağusa)