- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

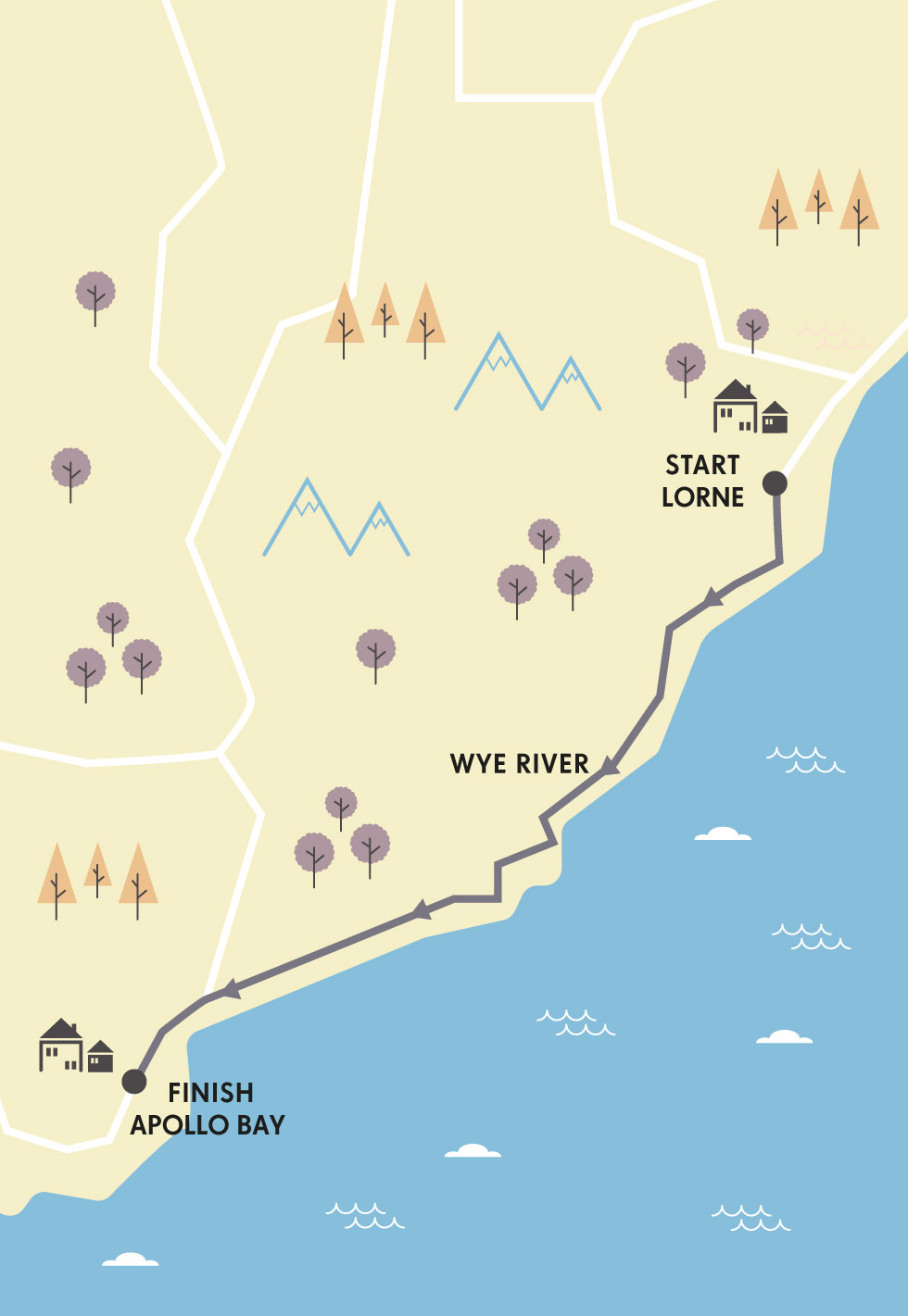

THE GREAT OCEAN ROAD MARATHON

Australia’s most scenic drive is also the venue for one of the world’s most beautiful marathons. And when you run it, you don’t have to keep your eyes on the road.

The first time I ran the Great Ocean Road Marathon I spent most of the time looking at, well, the Great Ocean Road. Don’t get me wrong, the road is in pretty good nick, considering the ridiculous number of cars that travel it every year. But it’s certainly not worthy of such a study. Out of the corner of my eye I saw others absorbing the views, looking at the amazing trees and out towards lonely driftwood-littered beaches. But I just kept looking down.

That marathon – at 27 miles (44km) it’s actually technically an ultra – was to be my longest run ever. And, looking back, I now see that idea weighed me down. So when I went back for another go, I made a promise to myself at the startline. No matter what, I would keep my head up. I would look out at the ocean. Soak up the visual splendour, the road clinging to the edge of the wild ocean, hugging huge rock cliffs and sandy beaches. I’d be one of the ones looking out.

One thing I had learned the first time around is there’s no point checking the weather in advance for the Great Ocean Road Marathon. Nature’s probably going to throw it all at you, no matter what the forecast says, and during my second go it was no different. The race is held in western Victoria, about two hours’ drive from Melbourne, in mid-May – the cusp of Austral autumn and winter, when the cold is arriving. The Great Ocean is actually Bass Strait. Apparently, explorer Matthew Flinders said of this area: ‘I have seldom seen a more fearful section of coastline.’

As I queue up to use the toilets before the start of the race in the resort town of Lorne, I gaze out at the water. Along this stretch, forest meets the sea, as eucalyptus trees come right to the road. It’s a sparsely populated area, with the occasional timber home perched on the side of a cliff. These are mostly everyone-knows-everyone towns.

© Posnov | Getty Images

Apollo Bay signals the last stretch of the race

I actually lived along here once, long before I was a runner. I’ve driven tourists along this stretch, cycled it in events and even researched the winding strip for guidebooks. But the Great Ocean Road only closes twice a year and the marathon is one of those times. No matter how many times I’d driven it, it feels like a rare, wonderful privilege to travel it car-free.

When we finally set off from Lorne, all I hear is the rumble of feet hitting the road. In fact, it almost drowns out a chorus of white and yellow cockatoos screeching their way through life on balconies. We leave the surfers bobbing in the water to the left of us, pass the new and improved Lorne pier, then Lorne Fisheries Co-Operative. The Grand Pacific Hotel, circa 1875, is on our right. Guests in full motorcycling gear cheer us on – they can’t go anywhere until we’ve gone.

Then, there’s nothing. The nothing’s always a shock. This is not a remote run – far from it. But, as the runners find their paces and thin out, I find my place and my pace. I also find solitude. It’s just me and the road, really, and the blue of the water, the green and grey of the trees. This race has actually morphed into a weekend-long Running Festival with a range of events, and there are almost 8000 people running in one or more of the races. Yet somehow, the thousands of other marathoners disappear.

© Courtesy of the Great Ocaen Road Marathon

the Great Ocean Road is closed to cars only twice a year

“A chorus of white and yellow cockatoos screech from balconies as surfers bob in the ocean to the left of us”

I mark my progress on the run by the towns I pass through, such as Wye River, which is now surrounded by blackened trees and bare land from a bushfire that wiped out many of its houses in 2015. Remarkably, the Wye River General Store was spared – it’s a great place for a coffee.

I had vowed to open my eyes to the sights, but I’m realising the scents change quickly, too, on the Great Ocean Road. Sea mist hangs in the air and there are patches where shaded rocky cliffs drip water, bringing the deep smell of the forest. Cuttingly cold wind can spring from nowhere. Last time, on reaching the top of one of the hills (the route has a 1600ft; 488m elevation gain), my feet were even lifted from under me by a gust.

Just over halfway through the marathon, at Kennett River, I remember to look up towards the local koala population that sits in the eucalyptus trees above. I don’t see any, so I look at my phone to see the time. I realise that the winner has probably already finished.

Yeah, I’m slow. I don’t always train. I get the dregs at the aid stations – the last slimy jelly snake. People are tired of cheering us on by the time I come through. I run with fit-looking people and feel good about myself – until we chat and I realise that they’re injured. No matter, things are going to plan, my plan of just taking it all in.

© Flemming Gregersen | Shutterstock

cockatoos roost on balconies along the way

Once we join the coast again, I see big white-froth-topped waves. It must be freezing out there, I think. Still, surfers persist in popular spots up and down this coastline. I always look out past the breakers to see if I can spot any blowhole spray on the horizon. No whales today. But there is a rainbow. And, of course, dark clouds out towards Apollo Bay way.

I feel good. The excitement of the start hasn’t diminished much, and the excitement of finishing is building. Still, my challenge with the Great Ocean Road Marathon is that the timing mat is under the cypress trees that line the entrance to Apollo Bay. You run over it, hear the beep, see your time (5:18 – told you I was slow). But there’s still over a mile (1800m) to go. It’s raining. If I’d run faster, I’d have stayed dry. Instead, I have to run faster just to get through it.

I wrap myself in a race towel, grab a finish-line banana and, with a couple of tears of success in my eyes, start searching for the bus that’ll take me back to Lorne. I get to travel the Great Ocean Road one more time today. JD

© Courtesy of the Great Ocaen Road Marathon

one of the marathon’s many rugged stretches

BUILT BY HAND

The Great Ocean Road was carved into land between the ocean and farms and forests by about 3000 returned WWI soldiers. They finished the job in 1932 and it became a toll road (it’s free now). Enjoy the retro charm of the over-the-road memorial arch on your way to Lorne – it celebrates the diggers who built it. In Kennett River, look up to spot koalas lazing and grazing in the gum trees.

ORIENTATION

Start // Lorne

End // Apollo Bay

Distance // 27 miles (44km)

Getting there // Lorne is 90 miles (145km) from Melbourne. The closest domestic airport, Avalon, is 55 miles (89km) away.

When to go // The third Sunday in May.

Where to stay // Great Ocean Road Cottages (www.greatoceanroadcottages.com) has great in-the-trees cottages as well as dorm-style rooms with cheap doubles.

More info // www.greatoceanroadrunfest.com.au

Things to know // Standard warm-weather running gear should suffice, but gloves may help you get through a chilly morning. A drop bag filled with a warm change of clothes is a good idea for the finish.

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

COASTAL MARATHONS

SURF COAST TRAIL MARATHON, TORQUAY, AUSTRALIA

This fun trail marathon takes runners alongside the stretch of the Great Ocean Road closer to Melbourne. Beginning on the beach in surf-loving Torquay, it follows the Surf Coast Walk to Fairhaven, 42km away. It passes by world-famous surf break Bells Beach, heads inland into the scrub at Point Addis, and includes plenty of sand running. At Point Addis, marathoners meet up with their half marathoner friends and continue on through the beachside towns of Anglesea and, finally, Aireys Inlet. It’s hard to stay dry with river crossings at high tide and some running at the edge of the sea. As you close in on the finish line, there’s the stunning Split Point Lighthouse to run towards before a sandy finish at Fairhaven Surf Lifesaving Club.

Start // Torquay

End // Fairhaven

Distance // 26.2 miles (42km)

More info // www.surfcoasttrailmarathon.com.au

BERMUDA MARATHON

Bermuda Marathon runners start in Hamilton, alongside the half marathoners. But when the latter are coming in to finish, the marathoners keep going and do another lap – but it’s not your usual lap: the route takes you from the start, past the Botanic Gardens, along the South Rd beside Bermuda’s south coast, past Harrington Sound, clear to Bermuda’s north coast. Bermuda’s pretty small – think 20 miles by 2 miles – so you sort of feel like you’ve run the whole country! Runners can expect a rolling course with pastel-coloured houses and mansions dotting the route. It’s a tropical location where you can stop to sniff the frangipani and bougainvillea. Fit folks can take on the Bermuda Triangle Challenge, which involves three races in three days.

Start/End // Hamilton

Distance // 26.2 miles (42km)

More info // www.bermudaraceweekend.com/race-info

© Cristina Lichti | Getty Images

Horseshoe Bay Beach, Bermuda

DINGLE MARATHON, IRELAND

You may recognise this craggy wave-scoured spot in southwest Ireland from Star Wars: Episode VII. And the filmset, since dismantled, could even be seen from Slea Head Dr, which forms part of the Dingle Marathon route. Regardless, if you run this race, you’ll be one of the lucky ducks who get to experience some of the most breathtakingly tall and rugged sea cliffs on the one day of the year that it is completely sans traffic. The run starts in the marina of the picturesque fishing/tourist town and gives you views of the Blasket Islands, ancient forts, anxiety-inducing cliffs and a lot of Atlantic Ocean.

Start/End // Dingle

Distance // 26.2 miles (42km)

More info // www.dinglemarathon.ie

© M Ramirez | Alamy Stock Photo

Ireland’s Dingle Marathon stretches from the country roads of County Kerry to stunning sea cliffs

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MELBOURNE’S MUST-DO PARK RUN

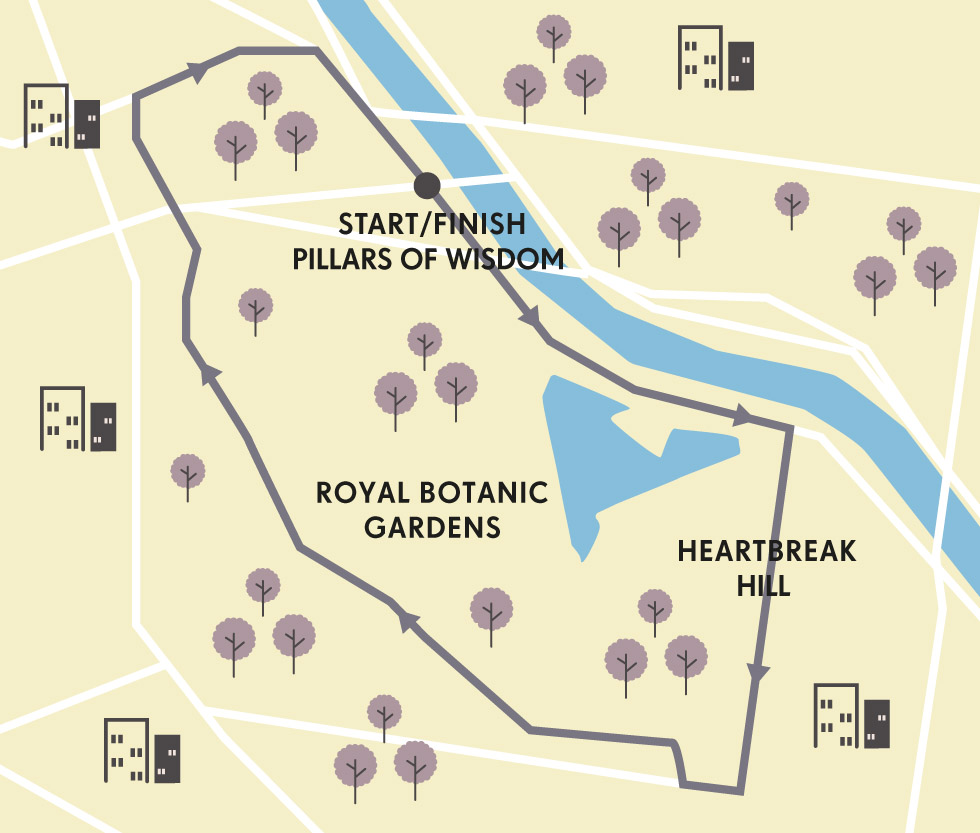

The ‘Tan’ is a legendary little loop that has everything a great city run should, and some wildlife that makes it one of a kind.

Runners have become a fixture in city parks the world over, whether they’re competing in an organised event or simply sneaking in a workout around office hours. At dawn we come out by the million, chasing an early morning high or seeking some zone 2 meditation. For some, a park run is an exercise in escapism, a chance to breathe more deeply or get a little further away from the exhaust fumes. For others, it’s all about PBs and Strava splits. Nowhere offers a more striking snapshot of this diverse congregation than Melbourne’s de facto trail-running temple: the ‘Tan’.

This two-mile route loops around the city’s impressive Botanic Gardens, in the shadows of skyscrapers north of the river, out towards the trendy ’hoods of South Yarra and St Kilda. Some locals do a lap every day; others might mooch around once in a blue moon. I run it every chance I get and am here once again this morning, with a head full of thoughts about how the Tan symbolises so much about the city.

© Takatoshi Kurikawa | Alamy Stock Photo

plentiful parks make Melbourne one of the most runnable cities in the world

“The Tan is a running nerd’s nirvana, with distance markers every 250m, digital clocks and lights that keep it navigable until the witching hour”

You can join the loop wherever you like, but the ‘official’ start point of a traditional lap of the Tan is the Pillars of Wisdom, on the south bank of the river, opposite Swan Street Bridge. From here, I like to set off clockwise along Alexandra Avenue, with the Yarra to my left and the ornamental lake on my right.

Melbourne is a truly multilayered metropolis. Obsessed with the arts, it’s a place where suits, students and skaters share the graffiti-tattooed alleyways and craft-coffee joints. But it’s also a city where every road seems to lead to a green space. Unsurprisingly, for a city steeped in sport of all kinds, the Victorian capital has perfected the park run concept, offering a route to suit every boot. Indeed, nearly 5-million square metres of grassy gardens and trail-striped public spaces punctuate the concrete jungle here.

© Timothy Christiant | Shutterstock

urban wildlife patrols the Royal Botanic Gardens

But the Tan tops the lot. Named after either the tanbark used for the original horse track built in the early 1900s, or as a shortening of the word Botanical – nobody can agree on which – the Tan is mostly on gravel with a bit of asphalt thrown in. So popular is the track that sometimes it looks as though a river of runners flows around this 94-acre (38-hectare) corner of semi-cultivated nature, cuddled by a bend in the Yarra River. The Tan is a running nerd’s nirvana, with distance markers every 250m and digital clocks, and it is well-lit until the witching hour.

But I mostly come here to break a sweat. The circuit’s sternest challenge comes quickly with the ascent of Anderson St, aka ‘Heartbreak Hill’. It gets the blood pumping around my muscles, which are still protesting the early start. The peak of this pinch point, though, reveals a sunrise-illuminated view across the serpentine coil of the Yarra and into the high-rises beyond. Next, I follow the track as it wends northwest, parallel to Birdswood Avenue, passing the Children’s Garden on the right and the solemn World War I memorial, Shrine of Remembrance, on the left.

© Uwe Aranas | Shutterstock

the Shrine of Remembrance war memorial

I once ran the Tan with elite American ultrarunner and mountain man Anton Krupicka, famous for his flowing locks, bushy beard and hoofing around the roof of the Rockies with next-to-nothing on. The terrain and busy trail couldn’t have been much further removed from his usual stomping grounds in the high, lonely peaks of Colorado. But ever-affable Anton seemed genuinely excited about the number of runners out on an ordinary workday morning. It was a privilege to share such an iconic track with a genuine star of the trail-running cosmos. But, to be honest, my most pleasurable runs here have all been much like this one, a few minutes past daybreak, just me and the trees, birds and beasts that call the Botanical Gardens home.

There’s something persistently wild about this run. Despite the digital timers and lights, the gardens are home to night herons, flying foxes and other nocturnal species, as well as thousands of birds and animals, including marsupial possums, as common here as squirrels are in the parks of London or New York.

Once beyond the Sidney Myer Music Bowl, I trace the track as it elbows back to Alexandra Ave to return to the Pillars of Wisdom. Here, a stone plinth celebrates the fastest Tan times ever recorded, with entries including bling-winning Olympians from Australia, Kenya and North America. I’ll never get anywhere near these times, but I couldn’t care less. In these precious dawn moments, as the earth spins and the southern city turns to face the sun, its towering steel-and-glass edifices are set aglitter with a magical light, and the birds of the Botanical Gardens twitter as they change shift.

They’re a noisy bunch, making a bewildering series of sounds, from the R2D2-esque wolf-whistle-come-fart of the white-plumed honeyeater to the low beatbox bass hum of the tawny frogmouth. Ever the tourist – despite a decade-and-a-half of habitual running visits to the park – I’m always most tickled by the kaleidoscopic clouds of rainbow lorikeets and rosellas that rampage through, as cacophonous as they are colourful. I can never understand how some of my fellow runners cut out this part of the experience with earphones.

And when the sounds of the city are drowned out by the noise of nature – be it dawn chorus or evensong – you can run right back into the Aussie outback here, even though you’re on the cusp of Melbourne’s CBD. Which is what makes this one of the world’s very best park runs. PK

PARK RECORD

On 21 December 2006, Australian 5000m specialist and four-time Olympian Craig Mottram set the current record for running the Tan with a time of 10 minutes and eight seconds. Mottram completed this run with players from the nearby Richmond Football Club – he gave the professional Australian Rules footballers a two-and-a-half minute head start, but still thrashed them.

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Pillars of Wisdom, near the junction of Alexandra Ave and Olympic Blvd

Distance // 2.4 miles (3.8km)

Getting There // The Botanic Gardens are a short walk from the city centre. Tram stop 19, at the Shrine of Remembrance/St Kilda Rd, will get you closest.

When to go // The Tan is mild all year round. Sunrise and sunset are prime times.

Where to stay // ’Burbs such as South Yarra, Prahran, Middle Park or St Kilda East, which are all close to the Tan.

More info // www.rbg.vic.gov.au www.onlymelbourne.com.au/tan-track

Things to know // Coffee has been elevated to an art form in Melbourne. Grab a post-run caffeine hit near the Tan at spots such as St Ali Coffee Roasters.

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

ICONIC PARK RUNS

PHOENIX PARK, DUBLIN, IRELAND

One of the largest walled green spaces in Europe, history-heavy 1,750-acre (708- hectare) Phoenix Park is home to a herd of wild fallow deer and multiple flocks of free-range runners. There’s no particular prescribed route to follow – joggers just follow their underfoot preferences, with road runners sticking to the tarmac tracks and trailhounds seeking out the softer and more technical pathways that wend between the trees. A lap of the park running parallel to the perimeter wall is 6.6 miles (10.5km), but there are many more interesting routes to explore, looping around sites such as Áras an Uachtaráin (official residence of the President of Ireland), Dublin Zoo, Wellington Monument and the 15th-century Ashtown Castle.

Start/End // Chesterfield Ave (route of Great Ireland Run)

Distance // 6 miles (10km)

More info // www.phoenixpark.ie

© David L. Moore - IRE | Alamy Stock Photo

Dublin’s Phoenix Park is one of Europe’s largest

ALBERT PARK, MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

Among the dozens of great urban runs to explore around Melbourne is one that gets people legging around the Formula 1 Grand Prix circuit in Albert Park. This grassy space sits between the city, St Kilda and Port Phillip Bay. A circumnavigation of Albert Park Lake is just a shade under 3 miles (5km), and this has become a popular place to set a PB, not least because of the weekly mass-participation park run event that happens every Saturday morning. The terrain is a rich mix of concrete, gravel and sandy paths, but by far the biggest hazard are the resident black swans, who don’t like to get out of the way for anyone. The course record is 14:29, although Michael Schumacher got around it in 1:24 in 2004.

Start/End // Melbourne Sports and Aquatic Centre (MSAC)

Distance // 3 miles (5km)

More info // www.parkweb.vic.gov.au; www.parkrun.com.au/albert-melbourne

BUSHY PARK, TEDDINGTON, LONDON, UK

Having begun as a brilliantly simple concept – a non-competitive, ultra-inclusive, timed, free, weekly 5km run in a public space – Parkrun is now a fully fledged global phenomenon, embraced by millions. And it all started here, when the 13 original apostles of Parkrun jogged around Bushy Park on 2 October 2004. Parkrun tourists travel around countries and continents ticking off new courses, and Bushy – as the epicentre of a running revolution – always tops their to-do list. Hundreds of Parkrun pilgrims visit every Saturday from all over the world, to run anticlockwise around the famous route. More than 1700 ran the 10th-anniversary event, and guest gallopers have included Mo Farah.

Start/End // Diana Fountain/Heron Pond, Bushy Park

Distance // 3 miles (5km)

More info // www.parkrun.org.uk/bushy

© Maurice Savage | Alamy Stock Photo

a fun run in London’s Bushy Park

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

THE ORMISTON GORGE POUND LOOP

This bite-sized offshoot of northern Australia’s famed long-distance Larapinta Trail could very well be the best short trail run on the continent.

The late, great Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira painted thousands of canvases depicting his exquisite backyard subject: the mesmerising Tjoritja, or West MacDonnell Ranges, in the Northern Territory of Australia. Famous for their rugged landscapes, Namatjira’s watercolours drip with light and colour, featuring stark white gum trees and the twisted scrubland that epitomises the harsh yet inviting outback. Never could Namatjira have imagined that his works would also act as a seed of inspiration for trail runners.

Flush with high escarpments and dramatic valleys ripe for exploration, Namatjira’s painting Near Ormiston Gorge was in fact the pictorial signpost that pointed me toward the West MacDonnell Ranges. Mile-for-mile, the Ormiston Gorge and Pound Loop is the best short run in Australia, period. At a bite-sized 5.6 miles (9km), this circular offshoot of the renowned Larapinta Trail – which stretches a full 140 miles (223km) and is a common multi-day walk or ultra-distance run – leaves straight from the Ormiston Gorge car park, offering an accessible, richly distilled taste of what it’s like to run the arid zone landscapes of Australia’s iconic Red Centre.

Indeed, my own first encounter with this single track came at the end of a 20.5-mile (33km) run under a skin-crinkling solar glare: my energy registered as bone dry as my hydration pack. I was leading a group of runners on a multi-day trail-running mission along the main Larapinta Trail. It had been a sturdy six hours of climbing high ridges and descending into gorges. But even beauty takes its toll when the environment is riddled with sharp rocks underfoot, thorny bushes to brush past and the odd King Brown snake to leap over.

© Bryce Thomas | Getty Images

Ormiston Gorge’s terrain is stunning but steep

“We hit the water’s edge and the trail disappeared into its depths. We waded in, run packs high above our heads”

Our group was halfway through an east to west tour and the idea of tacking on an extra five miles to capture the Ormiston Gorge and Pound loop was a nonstarter as we made a beeline for the air-conditioned confines of the car park’s kiosk and the ice cream for sale inside. We then hit the nearby swimming hole. However, after a soothing dip in the chilled waters of the gorge, the call of yet another potentially great run was too great. In fact, the thought of a mellow warm-down was even starting to sound like a good idea. And so, with legs sufficiently iced (we may be in the desert, but waterhole temperatures here remain stubbornly freezing), we set off.

Running back out of the car park – the route can be done in either direction, but counter clockwise is suggested so you finish off with a highlight water-crossing in the gorge – we picked up a trail we had ignored earlier. After crossing the dead-dry Ormiston Creek, it led northeast, away from the Larapinta Trail, gently meandering up an exposed valley.

© blickwinkel | Alamy Stock Photo

native spinifex plant

It’s easy to imagine – even for Antipodeans – that a run through the ‘Dead Heart’ of Down Under would be characterised by trackless sand dunes, baked by a searing desert heat. As it turns out, central Australia is not so bereft of life, nor as harsh a place to run as one would envisage. Indeed, the trails of Tjoritja are teeming with wild creatures, watery oases and giant mountain ridgelines that loom large over enchanting slot canyons and gaping prehistoric valleys, packed with exotic flora. Views are akin to imaginings of a Martian landscape, as sharp red and orange rocks glower at you from either side of a well-packed down trail.

As the orchestra of anticipation rose in volume, we reached a small saddle, where a short switchback deviation took us onto an exposed lookout. The reward was an astounding view that Namatjira would surely have judged worthy of a month sitting at the easel.

Before us sprawled ‘the Pound’, an immense bowl fringed by steep-sided mountains jutting up out of the flat, sandy floor. To the north is the majestic Bowmans Gap, a chasm that splits the final act of the Chewings Range, marking the northern boundary. To the east, the eyeline draws back to the dominant peak of Mt Giles (4557ft; 1389m), which stands sentry approximately 10kms away as the crow flies, at the eastern end of the crater-like enclosure. Both escarpments tower over Ormiston Creek and its dry tributaries, along with an abundance of spinifex, ever-present white ghost gums and a solitary winding trail that funnels into Ormiston Gorge itself.

© Andrew Bain | Alamy Stock Photo

trails often disappear into the drink

The northern wall felt immense once we were up close. Formed when one gargantuan block of quartzite slid atop another, in a powerful display of geological creation, it is a fortress-like monolith. Running into the gorge’s depths, the trail turns to sand before offering up some rock hopping, and a test of core strength and balance. The shadow of the cliff above was edging ever closer to engulfing us.

Eventually, we hit the water’s edge and the trail disappeared directly into its depths. There was no option other than to wade in up to our waist in the frigid waters, holding our run packs high above our heads.

From the crossing, we had a choice to remain low, rock hopping back around the waterway towards the sandy riverbank beach and campsite, or go high on the Ghost Gum Walk. The view was too much to resist so we went high. We reached a lookout over the gorge, and back up the chasm we’d just run. One lone ghost gum overlooks the gorge’s snaking crevice here: if only I had the talent of Namatjira and a canvas in my pack, I might have stopped to paint the scene. Instead, a second ice cream awaits in the kiosk below. CO

GOING THE DISTANCE

The fastest known time running west to east along the entire 140-mile (223km)-long Larapinta Trail – which encompasses 13,000ft (3965m) elevation gain – is 58 hours and 48 minutes. It was set by Simon Duke and Rohan Rowling in 2018. Chris Macaskill-Hants holds the FKT east to west (61hrs 32mins, 2014), which is believed to be the more challenging route.

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Ormiston Pound car park

Distance // 5.6 miles (9km)

Getting there // The Ormiston Pound car park and camping site is 84 miles (135km) west from Alice Springs, Northern Territory.

When to go // May–October.

Where to stay // Camping and van sites at Ormiston Pound with attendant kiosk.

More info // www.nt.gov.au/leisure/parks-reserves

Things to know // Take care when crossing the water body towards the end of the counterclockwise loop, it can reach up to your waist or so. Once you have crossed the water, you can choose to take the low or high route to return to the Ormiston Pound car park.

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

OFF-ROAD RUNS IN OZ

CARNARVON GORGE, QUEENSLAND

Carnarvon Gorge is a hidden gem worth the long journey inland to access it. The national park features towering sandstone cliffs, gorges aplenty, spurs and ridgelines, sweeping table lands, diverse flora and fauna and an abundance of Aboriginal rock art. The main 54-mile (87km) circuit can be run in sections – there are five campsites en route. We suggest a 2–3 day run mission carrying all you need to be self-sufficient. Or stick with short out-and-backs on trails ranging from 1 mile to 12 miles, return. The gorge is home to a range of significant plant species including remnant rainforest in sheltered gorges, endemic Carnarvon fan palms, ancient cycads, ferns, flowering shrubs and gum trees. The ochre stencils, rock engravings and freehand paintings are regarded as some of the finest Aboriginal rock art in Australia.

Start/End // Carnarvon Gorge Visitor Area

Distance // 1–54 miles (1.5–87km)

More info // www.npsr.qld.gov.au/parks/carnarvon-gorge

FLINDERS RANGES INCLUDING WILPENA POUND, SOUTH AUSTRALIA

Located a few hundred miles north of Adelaide, South Australia’s largest mountain range plays host to the iconic natural amphitheatre that is Ikara (Wilpena Pound), along with the Heysen Range, and Brachina and Bunyeroo gorges. It is a beacon for arid-zone trail running. Artist Albert Namatjira made the West MacDonnell Ranges famous, so too the Flinders Ranges were popularised by the works of German painter Sir Hans Heysen. Rugged mountain scenery, gorges, plentiful wildlife and flora can all be explored via more than two dozen primary walking tracks, including our favourite, the St Mary’s Peak Loop. But options are endless along the 750-mile (1200km) Heysen Trail, which stretches all the way south to Cape Jervis.

Start/End // Wilpena Pound

Distance // 12 miles (19km)

More info // www.heysentrail.asn.au

LARAPINTA TRAIL, NORTHERN TERRITORY

If you want more than a taste and are trained up enough for the main course, then hit longer sections – or all of – the Larapinta Trail. You can run it in either direction, although many runners prefer to go from east (Alice Springs) to west (Redbank Gorge), so as to reward themselves at the end with the 10-mile (16km) out-and-back up to Mt Sonder, best completed at sunrise. It can be done self-sufficiently if you fastpack with food drops or use local transport companies. Better yet, there are trail-run tour companies that can guide you along highlight sections. You can also enter the Run Larapinta multi-day event for four section highlights amid a friendly but competitive environment.

Start // Alice Springs

End // Rebank Gorge (Mt Sonder)

Distance // 140 miles (223km)

More info // www.larapintatrail.com.au

© Chris Ord

Australia’s 140-mile-long Larapinta Trail is one of the continent’s most famous multi-day runs

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

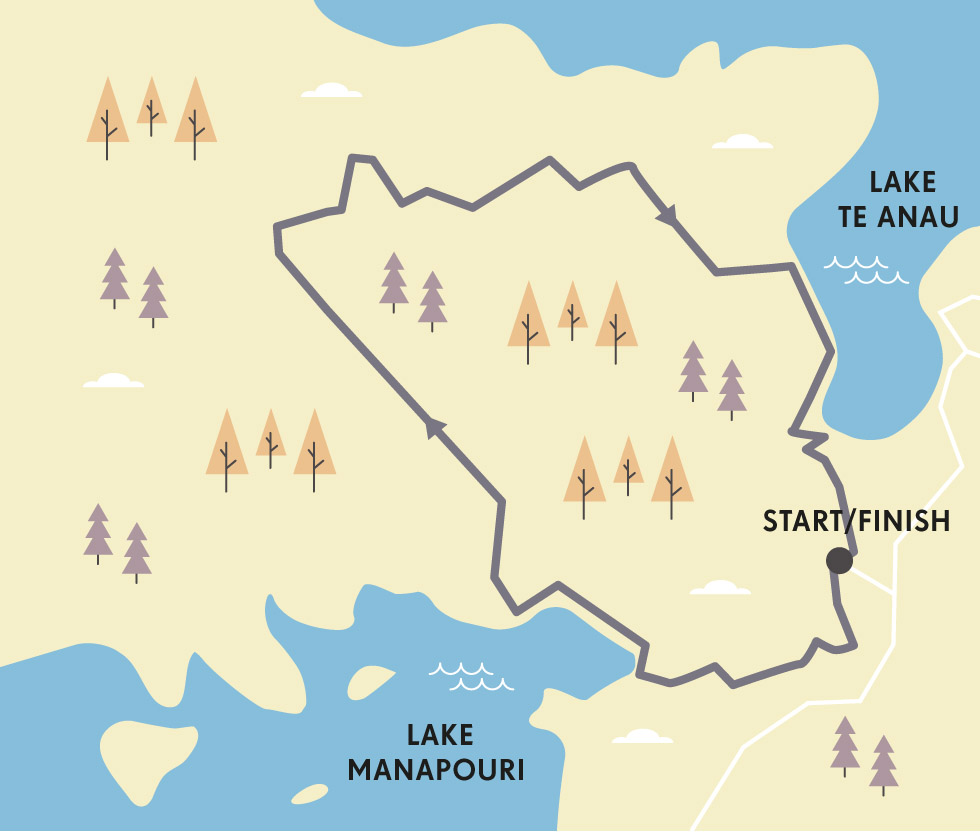

THE KEPLER TRACK

Carrying you across mountaintops and along some of the world’s most stunning ridgelines, New Zealand’s ‘Great Walk’ seems far more suited to ambitious trail runners.

The wind had been howling like an aggrieved banshee from the moment we set out along the 36-mile (58km) Kepler Track. But it wasn’t the elements that literally floored me. It was overexcitement – and a little stupidity – as I stopped concentrating on the rock-strewn path in front of me and attempted to take a mid-stride photo of my running buddies legging it straight into a scene from a dream. The Kepler Track is indeed the sort of dream a trail runner might experience after scoffing too much cheese just before bedtime, having nodded off while fantasising over photos of wild singletrack, forest trails and knife-like ridgeline routes. Thankfully, I was not dreaming. This was the real deal. But face-diving the trail woke me up to a certain reality: if I didn’t watch my step, I might take a tumble right off the side of this rocky ridge and not even live long enough to brag about my accomplishment.

It’s no fluke that New Zealand breeds legendary adventure athletes such as Richard Ussher and Anna Frost. Dangling at the bottom of the globe, with a national population half the size of London’s, the Land of the Long White Cloud is also the home of countless long trail-running routes. These are tracks as lonely as they are lovely, snaking across terrain so varied it feels as though it can’t possibly all belong to the same planet, let alone a single country.

Active volcanoes, ancient rainforests, titanic fjords, heaving glaciers, perpetual waterfalls, bubbling mud fields, snowcapped peaks and empty ocean-stroked beaches – all just everyday wallpaper for spoilt Kiwi trail runners. Nine of New Zealand’s tracks are so exceptional they’ve officially been bestowed with the appellation Great Walk. But any trail that can be tramped can also be trotted, as I discovered during an expedition where – with two fleet-footed friends – I was running the full list.

The Milford Track is often touted as New Zealand’s very best trail, partly because it inspired the Great Walks concept, but also because it’s an undeniably sensational journey through the otherworldly surrounds of the South Island’s Fiordland National Park. For me, though, having jogged the job lot, the Kepler Track offers the ultimate challenge for trail runners looking to explore the country’s rough-edged riches.

For starters, it’s a circular route, which makes logistics much easier, and you can decide which way to go according to conditions on the day. But whichever direction you take, it’s the stunning variety of the terrain that elevates it to epic status. You travel from calm, tree-fringed lowland singletracks that skirt the lake to the exposed, wind-blasted and blade-shaped ridgeline across Mt Luxmore.

© Courtesy of Kepler Challenge | Graham Dainty

ridgelines keep things interesting

We decided to run anti-clockwise, leaving Lake Te Anau trailhead along a track that shadows the shoreline of Australasia’s biggest freshwater puddle. This short stretch is flat and pretty, wending through beech forest and giant ferns. But after Brod Bay the path abruptly reared like an angry snake as the ascent of Mt Luxmore began. Threading through tight tunnels in-between imposing limestone bluffs, the track climbed mercilessly, scaling more than 1500ft (450m) in nearly two miles (3km) before popping out of the treeline, exposing us to a wicked westerly wind that forced a decision to pause and layer-up.

We had the path to ourselves, but in a couple of months the Kepler Challenge would see hundreds of competitors tackle the 37-mile (60km) route, some finishing with sub-5-hour times. Plenty of people will take twice that time, though, and this is an ultra-distance run that anyone with mid-level experience and fitness can realistically do, if they approach it sensibly. Or, if the whole-loop length is too intimidating, it can also be tackled in stages, with overnight rest stops in excellent huts, allowing time to explore super-interesting side attractions (including caves near Luxmore Hut and a wonderful waterfall close to Iris Burns Hut).

Most of those who have just a day turn around at Luxmore Hut to wend and descend back to the trailhead. This 17-mile (27km) out-and-back is the route of the Luxmore Grunt, a race held annually on the same day as the Challenge. While these events feature on many a runner’s bucket-list, I prefer to meet my mountains minus the crowds – and the conditions that accompanied our Kepler canter were ensuring just that.

‘Dress to stay warm and windproof.’ This was the sage advice scrawled by ‘Ranger Peter’ on the whiteboard in Luxmore Hut. He had used the double O in ‘windprOOf’ to form a pair of eyes in a grinning cartoon face. Then, in a more serious font, sans smiley anything, he suddenly segued into business mode: ‘Northwest winds rising to severe gales in exposed places. Snow to 1100m overnight.’ This forecast was one reason we met only one other human during our adventure, which would be unthinkable on the perennially popular Milford Track, whatever the weather.

After refuelling on trail mix we pushed on and, following a brief climb to the brow of 4829ft (1472m) Mt Luxmore, received a reward in the shape of some top-shelf ridgeline running. Charging along 7 miles (12km) of flowing summit-hugging singletrack, we peered down through the clouds at Te Anau’s sprawling South Fiord and gazed across the range to the snow-dusted Murchison Mountains.

At Hanging Valley emergency shelter we hid from the wind for a quick lunch, jealously protecting precious rations from a couple of keas, the tenacious mountain parrots that boldly boss the highlands of Te Wāhipounamu. And then it was time to stop fighting gravity, and to surf it instead, starting with a dramatic drop down Iris Burn.

easy terrain is the exception

COMPETE ON THE KEPLER

One of the world’s great mountain races, the Kepler Challenge has been run annually since 1988, three years after the Kepler Track opened. The field is limited to 450 competitors, and entries always sellout within five minutes of opening. The record for the full 37-mile (60km) course is a staggering four-and-a-half hours, set by Martin Dent in 2013. If you’re up for the challenge (of getting a place, let alone finishing), visit www.keplerchallenge.co.nz

“We jealously protected precious rations from tenacious keas, the mountain parrots that boss the Te Wahipounamu highlands”

The track swept around a seemingly endless section of sharp-elbowed switchbacks to the eponymous hut, from where the long, largely level 20-mile (32km) run-out begins. Quickly this became a race – us versus our nearest star – as we sought to complete our feat before the sun hit the horizon. Dropping through a gorge, we scaled the scar of an earlier avalanche and entered the protection of a podocarp forest before reaching Moturau Hut, which is perched on the beautiful banks of Lake Manapouri.

runners ready for the start of the Kepler Challenge

From the swing bridge at Rainbow Reach, the Waiau River took us to the trailhead and we finished with just enough light left in the day to read the sign we’d rushed past 10 hours earlier. It waxed lyrical about the Kepler being a Great Walk. We agree. But, arguably, it’s an even greater run. PK

© Courtesy of Kepler Challenge | Graham Dainty

it’s a bucket-list ultramarathon

ORIENTATION

Start/Finish // Kepler Track Car Park on Lake Te Anau

Distance // 37 miles (60km)

Getting there // The best access to the trailhead is via Queenstown or Te Anau.

When to go // The Great Walks season runs from late October to late April, during which time the track might be busy. Outside of this period, conditions can be harsh – potentially deadly – and not great for running.

Where to stay // Te Anau is the gateway town for Fiordland and has a broad range of options (www.fiordland.org.nz).

More info // www.doc.govt.nz/keplertrack

Things to know // Always check the forecast carefully, no matter how clear the conditions look. Things change quickly in New Zealand. And pack more than you think you’ll need: waterproof and windproof outer shells, calories (you will burn them big time on the climb).

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

OFF-ROAD RIDGELINES

DODO RUN, MAURITIUS

Sitting pretty in the midst of the Indian Ocean, Mauritius is known for its famed-but-long-extinct flightless bird, flashy weddings and beautiful beaches. But there are also gritty trails and sweaty runners. Indeed, a strong running culture exists here and – as veterans of the Dodo Trail (an event named after that aforementioned flightless bird) will attest – the tropical island offers myriad sensational sky running routes. The most epic of these traces the course of the Xtreme race, rollercoastering across the ridgeline of the Black River Range. It starts at the foot of Le Morne Brabant and scales Piton de La Prairie (550m), Piton du Fouge (660m), Montagne la Porte (550m) and Piton Canot (550m) to reach the roof of the island, le Piton de la Rivière Noire at 2716ft (828m), before descending via Black River Gorges and finishing at Tamarin.

Start // Le Morne Brabant

End // Riverland Sports Centre, Tamarin

Distance // 30 miles (50km)

More info // www.dodotrail.com

THE RAZORBACK, VICTORIA, AUSTRALIA

Mt Feathertop (6306ft; 1922m) is far from Australia’s highest peak, but it holds the country’s classic alpine challenge – known as the Razorback – with the route between its peak and nearby Mt Hotham (6105ft; 1861m) commonly considered one of the southern continent’s best ridgeline runs. Sitting in Victoria’s stunning Alpine National Park, it offers several variations to match your fitness, ranging from a 40-mile (64km) ultra to the 13.6-mile (22km) short-course ridge run. Sitting between these, the 24-mile (40km) Razorback Circuit is an excellent option for those wanting to taste the cream of the Victorian High Country, with the route running up Bungalow Spur, traversing the Razorback and crossing to Diamantina Spur, before heading down Bon Accord Spur.

Start/End // Harrietville Caravan Park or Diamantina Hut

Distance // 24 miles (40km)

More info // www.runningwild.net.au

HIMALAYA RUN & TREK, INDIA

One of the world’s oldest annual trail-running events, the Himalaya Run & Trek (HRT), is a five-day epic that begins in the tea plantations near the sky town of Darjeeling in West Bengal, and runs a ring route through the clouds, tracing the vertiginous border between India and Nepal. The views along the 100-mile (160km) route, which for several days features five of the world’s six highest peaks (Everest, Kanchenjunga, Makalu, Lhotse and Cho Oyu) take away any breath the altitude might have left in your lungs. If five days of running sounds too much, the middle day can be done as a standalone 26-mile challenge. It travels from the Himalayan eyrie of Sandakphu to the river-side settlement of Rimbik, under the eyes of the planet’s most famous mountain range and through stunningly pretty flower-bedecked valleys and villages. This is arguably the world’s most beautiful marathon.

Start/End // Maneybhanjang (full five-day circuit)

Distance // 100 miles (160km)

More info // www.himalayan.com

© Nitish Waila | Alamy Stock Photo

28,169ft (8586m) Kanchenjunga towers in the distance during India’s Himalaya Run & Trek

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

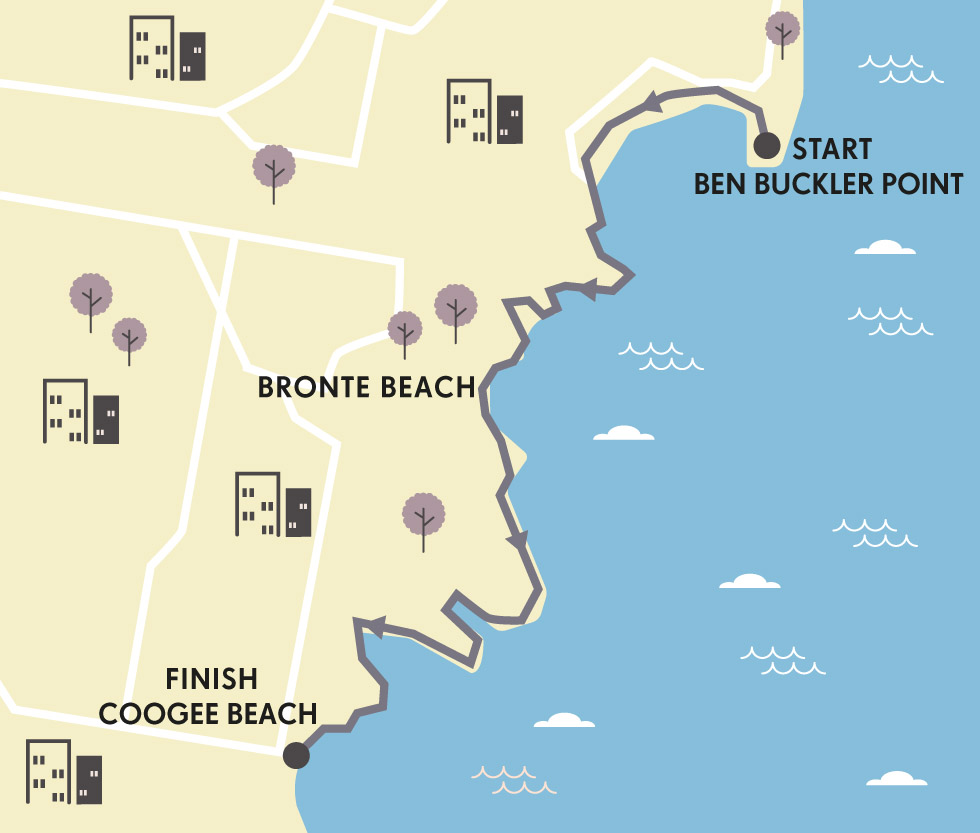

SYDNEY’S SPECTACULAR SEAFRONT

The famous ocean-hugging track between Bondi and Coogee beaches is stunning. But an annual outdoor art-show holds its own in competing for your attention.

As if the coastal views from the cliff tops overlooking Sydney’s Tamarama Beach aren’t stimulating enough, someone has seen fit to exercise my imagination even more with some seriously abstract alfresco art along the way. During a dawn run, I’ve come across a mob of man-shaped figures, who fail to return my g’day as I gallop past.

Turns out, this gang of eyeless effigies, staring out across the Southern Ocean, is part of Sculpture by the Sea, the world’s largest free public art installation. Spread out over a little more than a mile, beyond Bondi, this annual two-and-a-half-week festival features works by Aussie and international artists, some of which can be mind-meltingly modern, others pleasingly thought-provoking. Once a year, far from the confines of a gallery, these free-range artworks are let loose along the first part of a 4.2-mile (7km) trail between Bondi and Coogee beaches in Sydney’s southern suburbs.

This same stretch also holds the distinction of being one of the most famous seaside strolls in the southern hemisphere. Tracing the epic coastline, and linking the beautiful beaches that help make Sydney one of the most desirable and liveable cities on earth, this suburban pathway is a constant reminder for locals about how bloody blessed they are, with or without world-class art as a sideshow.

© stevecoleimages | Getty Images

Sydney’s famous Bondi Beach

“At Clovelly Beach, home to one of the oldest surf lifesaving clubs, a school group is taking board-riding lessons – how different this is to my own PE education”

But as popular as this path is, in the hours either side of daybreak it’s much more of a running route than it is a walkway. Long before the ramblers, amblers, backpackers and tourists take to the track, runners bowl through in both directions, on cobweb-clearing morning missions.

I catch the first bus to Bondi with my gear already on, not expecting to gallop around an art show. Instead, I am merely looking forward to a run in the early morning sun, around some of the most spectacular shoreline on the planet. Bondi is, of course, well known beyond Australia, but the truth is, it’s only the launch pad for a journey that takes in much better spots.

© Sue Martin / Alamy Stock Photo

Mackenzies Bay

From Ben Buckler Point in North Bondi I run around the curve of the famous beach and past a monument to Black Sunday, a dark day in 1938 when a series of monstrous waves washed hundreds of people into the sea, drowning five of them. Such scenes are hard to imagine on a calm bluebird morning, but I soon see powerful surf sending spray surging into the saltwater pool at Bondi Icebergs Club, an iconic ocean-fed swimming spot on Notts Ave. It’s here that the path begins toward Coogee.

© Andrew Watson | Alamy Stock Photo

the path from Bondi to Coogee

As tempting as the water looks, I continue cantering south on the doubletrack concrete waterfront walkway as it drops between the rocks and then rises to round Mackenzies Point, where a newly restored ancient Aboriginal rock carving of a giant ray can be seen. This landscape has been inspiring artists for centuries – maybe millennia. Some of the 225-million-year-old sandstone cliffs around here are topped by rocks decorated with ancient indigenous carvings depicting marine animals.

This morning, much more modern and totally transitory artwork lines the trail. Here’s a giant mirrored igloo-like thing. A few paces further I find a pile of precariously balanced boulders, spilling across the grass of Marks Park. And then there’s the gang of silent statues, encountered as I round Mackenzies Bay and meet Tamarama Beach, where hundreds of bikini-wearing, budgie-smuggling sun-worshipers will give my silent featureless friends something to stare at soon enough. Surely there’s a sign explaining all this somewhere, but those are for the walkers. I simply carry on past, happily applying a narrative layer of my own conjecture to the strange scene. Which is what such art is all about, surely.

What follows is a sort of greatest hits of Sydney’s beaches and coves. I bid the sculptures adieu and bound on to Bronte, the best of the beaches in my humble opinion thanks to barbecues in the verdant park, beautiful body-boarding conditions and a free-to-use tide-fed pool for swimming laps. I then trace the track south, past Calga Reserve and into Waverley, to wend along the famous boardwalk that skirts a cemetery with killer views of a restless ocean

© Manfred Gottschalk | Alamy Stock Photo

‘Red Trumpet Red Table’ by Philip Spelman, part of Sculpture by the Sea, 2014

Beyond the boardwalk, after a little hook round Shark Point, I run round the corner into Clovelly, another cracking beach cuddled in the arms of a yet another cove and home to one of the world’s oldest surf lifesaving clubs. This morning, a school group is taking to the waves for a board-riding lesson, giving me pause for thought about how very different this is to PE lessons during my own education. I hope these kids appreciate how lucky they are.

I’m feeling pretty fortunate myself, though, feet floating on freshly released endorphins, until Cliffbrook Parade brings me back down to earth. This passage, linking Clovelly to Gordons Bay, is a quads crusher, but it all feels worthwhile when I pop out the other side into a beautiful bay accessible only by boat and foot. I can see snorkellers and divers are already taking to the gin-clear water for an early morning aquatic adventure.

The chill of the dawn has long since lifted and I’m cloaked in sweat. One last push around Dolphin Point and past the sombre bronze linked figures that form the memorial to the Bali bomb victims takes me into the welcoming arms of Coogee. And now, a decision: do I run back, walk, or wimp-out and get the bus? There’s only one real answer to that – it’s too good a trail not to trot twice. Although perhaps I’ll take it easy on the return leg, stopping to absorb the artwork along the way. PK

HISTORY MYSTERY

One non-indigenous rock carving above the ocean in North Bondi is believed by some historians to depict a Spanish sailing ship, accompanied by Roman-style lettering interpreted as an assertion of conquest. It’s a controversial belief, as it would mean the Spanish beat Captain Cook to Australia’s east coast by some 200 years.

ORIENTATION

Start // Ben Buckler Point

Finish // Coogee Beach

Distance // 4.3 miles (7km) one way

Getting there // The train from Town Hall to Bondi Junction takes 11 minutes. Numerous buses take you to the beach.

When to go // Sydney is pleasant year-round. Sculpture by the Sea takes place late October to early November.

Where to stay // Bronte, Clovelly and Coogee all offer arguably better beaches than Bondi, with accommodation near the ocean and a little less boisterousness.

More info // www.sculpturebythesea.com

Things to know // If you’re in Sydney in August consider joining 80,000 runners on the City to Surf run from Hyde Park in the CBD to Bondi Beach.

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

SYDNEY’S SUBURBS

MAROUBRA TO MALABAR

The Bondi-to-Coogee route is a classic coastal run when done at dawn, but at other times it can be frustratingly busy. This route, slightly further south, provides a much less travelled but every bit as beautiful alternative. Start from the southern end of Maroubra Beach and simply keep the Southern Ocean on your left, while running bush-lined trails that trace the dramatic headland cliffs past Magic Point. Carry on around Boora Point and into Long Bay, before hitting another belter of a beach at Malabar. For a longer run, continue on to La Perouse and Unesco World Heritage-listed Bare Island in Botany Bay, via Little Bay, Cape Banks, Henry Head and Little Congwong Beach.

Start // Maroubra Beach

End // Malabar Beach (or La Perouse for the longer option)

Distance // 2.8 miles (4.5km)

More info // www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au

ROYAL BOTANIC GARDEN TO BARANGAROO RESERVE

Sydney might boast most of Australia’s oldest and most recognisable structures, but it’s a city in a constant state of evolution, making it all the more fascinating to explore on the hoof. This linear run begins in the beautiful Royal Botanic Garden and skirts along the shoreline overlooking Woolloomooloo to Mrs Macquarie’s Chair, an exposed sandstone pew poking into Sydney Harbour. Views of the Harbour Bridge are superb. But carry on around Circular Quay and past the famous Opera House to get even closer to the iconic span. Continue through The Rocks, the city’s oldest quarter, to Barangaroo Reserve, a fantastic foreshore park that opened in 2015.

Start // Corner of St Mary’s and Prince Albert roads

End // Barangaroo Reserve

Distance // 3 miles (5km)

More info // www.barangaroo.com

© Olga Kashubin | Shutterstock

Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden

LANE COVE NATIONAL PARK

A world away from the busy eastern suburbs, this national park on Sydney’s sensational North Shore offers runners an escape along some quiet and wildlife-rich routes that are as rewarding as they are challenging. A circular off-road foray follows the south bank of Lane Cove River from the Chatswood end of the park along the red gum-lined Riverside Walk to De Burghs Bridge. Here, you can cross the water and return along the opposite bank, taking the Lane Cove Valley and Heritage walking routes. Look and listen out for kookaburras and lorikeets that live among the eucalypts, caves and rocky outcrops. A 10km sealed-surface option out-and-back along Riverside Rd might appeal to road runners, but the elevation is brutal.

Start // Delhi Rd bridge

End // Chatswood

Distance // 7 miles (11.2km)

More info // www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au

© ITPhoto | Alamy Stock Photo

Barangaroo Reserve, with Harbour Bridge in the background

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

ULTRA-TRAIL AUSTRALIA

Formerly known as the North Face 100, this gorgeous tour of the Blue Mountains remains the most famous long-distance race in the southern hemisphere.

Ten kilometres,’ they said. ‘You’ll only need to run the final 10 kilometres.’ I had been assigned to write a profile of Dean Karnazes, one of the most famous ultramarathon runners in the world. The venue for our interview would be the Ultra- Trail Australia trail-running festival (back then called The North Face 100). It’s the biggest trail ultra on the continent and one of the biggest in the world.

Karnazes was, of course, planning on running all 100km. Whereas the longest run I had done in any one stretch in my entire life was 8 miles (12km). So when organisers told me I could be dropped a mere six miles (10km) from the finish line I believed them. And that’s how I ended up running my first ultra, by accident.

As I headed towards the undulating Blue Mountains World Heritage Wilderness, east of Sydney, I couldn’t help but second-guess my training regimen. When it comes to the UTA, they say you should train for uphills, downhills and stairs. And regardless of whether you’ve entered the 13.6-mile (22km) distance or the ultra distances of 31 or 62 miles (50/100km), they all require preparation.

© Pete Seaward | Lonely Planet

the Three Sisters rock formation above Jamison Valley

I, however, didn’t think I had to train, boldly calculating that a measly 10kms could be ‘cheated’ by a mid-thirties Average Joe like me who was in reasonably good shape. I did a total of two 5km outings in the two weeks prior and figured that should do the trick. And it might have, had the race organisers not accidentally dropped me off at the halfway mark of the full 62-mile (100km) distance.

But I still had a job to do. Thankfully, as I met up with Karnazes, he immediately began to relay anecdote after anecdote about a life of adventure running, providing great fodder for my article. And the landscape was truly magnificent. The towering cliffs and rock formations of ‘The Blueys’ attract 6000 participants from all over the world, many of whom flock to the event year after year, hydropacks, grippy shoes and grittier determination at the ready.

Like Karnazes, they are attracted not just by the glitz of the biggest showpiece of trail-running Down Under, but by the sheer beauty of the trails that crawl up, down and along soaring cliff-lines, ridges and escarpments with alluring names such as Narrow Neck, Iron Pot Ridge, Honeymoon Lookout and the aptly named Sublime Point. The 4500-plus metres of ascent includes brutal climbs up Golden Stairs, Taros Ladder and, of course, Furber Steps – 998 stairs ascending approximately 650ft (200m) at the final stretch.

© Chris Ord

surrounded by eucalyptus in Blue Mountains National Park

It’s not just the climbing that takes one’s breath away. The Megalong Valley is remote and bucolic. The Six Foot Track section is quintessential Australian bush running, and the course passes waterfalls in the eastern ramparts. The Grand Clifftop Track demarks the cafe-packed villages and quiet residences of the Blue Mountains while passing through the deep and dramatic wilderness of the national park and Jameson Valley, 2000ft (600m) below.

“I made a pact with Karnazes: if he kept going, I would, too, and try to complete my first ever ultramarathon”

Trying to pretend I could somehow keep up with a man best known for running 50 marathons in 50 states in 50 days, I walked gingerly backwards up a steep mountain in the Megalong Valley. I was now an unofficial participant in Australia’s biggest trail-running ultra. The denial was powerful as I simply focused on the few feet in front of me, and on prying more great material from Karnazes.

It turned out he had had a shockingly bad first half of the race and, by the time I joined him, was contemplating dropping out. That’s when I did something that, to this day, I can’t quite understand: I made a pact with him that if he kept going then, in return, I would try to complete my first ever ultramarathon off the back of zero training. Unfortunately, he agreed.

© Chris Ord

prepare to climb a lot of stairs

After about 18 miles (29km), no pretty name or postcard-worthy view could numb the fatigue. Even worse was the pain and dread of the final push as I looked up at twinkling lights blinking through the treeline high above, signalling the far-away finish line. But as I edged closer to the base of the final cliff, I could hear the crowd roaring for those runners who were already crossing the line. It sounded so close it fooled me into thinking I was about to complete my first ultra. But then I spotted a trail-side sign indicating six miles to go. My hopes were dashed. My legs suddenly felt like jelly and my stomach dropped at the thought of the climb ahead.

Mr Ultramarathon Man, Dean Karnazes, had the good wisdom to cut me loose long before, sprinting off not long after our final checkpoint. And once he felt the pull of the finish he did what any elite runner would do and picked up the pace for a respectable finish time of 14 hours and 42 minutes. He did say before leaving me in the dust that this was one of the toughest he’d done. I concurred.

I, on the other hand, ended up finishing a slice before midnight – a full three hours behind Karnazes. But I finished. I had unintentionally run my first ultra – the first of what is now 30 and counting. Admittedly, I have yet to officially enter the full 62-mile (100km) main event at Ultra-Trail Australia. But having now run both of the shorter distances several times each, including large sections of the longer ultra course, it’s officially on my bucket list. And I’ll probably train for it when I do it. CO

AUSSIE ELITES

During the 2010 UTA, Australians Stuart Gibson and Andrew Lee finished in a dead heat (in a time of nine hours, 31 minutes and 11 seconds), after going toe-to-toe for the last dozen miles. They crossed the line holding hands, something the pair are now often teased about. In 2014, Gibson again tied for first, this time alongside Andrew Tuckey. They didn’t hold hands.

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Scenic World, Katoomba, Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area

Distance // 62, 31 or 13.6 miles (100, 50 or 22km)

Getting there // Katoomba is roughly 2 hours’ drive west of Sydney.

When to go // The trail-running festival happens every May (though trails are open all year round).

Where to stay // There are hotels, motels, B&Bs and hostels in Katoomba, Leura and Wentworth Falls.

More info // www.ultratrailaustralia.com.au

Things to know // UTA is a ‘runners’ ultra, in that there are long sections of non-technical fire road. Nonetheless, it’s unwise not to train for steep terrain and lots of stairs, going up (hamstrings) and down (quads).

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

ANTIPODEAN TRAIL-RUN FESTS

TARAWERA TRAIL RUN, NEW ZEALAND

Tarawera Ultramarathon is New Zealand’s biggest trail-running festival, held annually in February. Part of the much-acclaimed Ultra-Trail World Tour, the event boasts a line-up of 100 mile (162km), 63 mile (102km), 31 mile (50km) and 12.4 mile (20km) distances, exploring the Rotorua wilderness on the North Island. The course runs through places that have deep cultural significance to local Maori people, with natural highlights including seven lakes, thick forests and a myriad of waterfalls. Around 1500 participants compete, including some of the world’s best runners. The trails are runnable, scenic and point to point. Every finisher receives a beautiful locally inspired wooden medal (the 100-mile finishers get a pounamu pendant).The two longer distances are both qualification races for the Western States 100 Mile Endurance Run, while the longest is also a qualifier for the Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc (UTMB).

Start/End // Rotorua, New Zealand

Distance // 12.4–100 miles (20–162km)

More info // www.taraweraultra.co.nz

© Hagen Hopkins | Getty Images

the running continues long after the sun sets at New Zealand’s Tarawera Trail Run ultramarathona

WARBURTON TRAIL FEST, AUSTRALIA

The newest kid on the Australian trail-running festival block, this one’s a little different. Sure, spread over three days in mid-March, it boasts a tough 31-mile (50km) mountain range-crossing Lumberjack Ultra – so named in honour of the sawmillers who worked the region in the mid 19th century – a 13.6-mile (22km) up-and-back mountain climb with 3280ft (1000m) of ascent, and a couple of mid-distance races, as well as a 3-mile (5km) fun run. But what marks the Warburton Trail Fest as a little more eccentric than most is the ‘Multiday Madness’ entry option, whereby participants take on as many of the events as possible, for an overall crown. The finale event is a short 1-mile trail run that then finishes with a 1-mile paddle down a river on lilos. And yes, you have to carry your lilo for the initial run leg! Dress-ups are encouraged.

Start/End // Warburton, Victoria

Distance // 2–31 miles (3–50km)

More info // www.warburtontrailfest.com

GONE NUTS 101, TASMANIA

Named after Tasmania’s imposing volcanic plug known as ‘the Nut’, this two-year-old race held every March has three different distances: 63, 31 and 15 miles (101km, 50km and 25km), which start in Stanley, Rocky Cape National Park and Boat Harbour respectively, and finish in Wynyard. Largely a coastal run, the terrain includes everything from singletrack that travels over windswept bluffs to sand and pebbles underfoot, as runners traverse pristine beaches. But inland stretches bring you deep into the bush along rough 4WD tracks and overgrown trails, with stream crossings across the Millicent Valley. The climbs promise to be challenging but fun, as the undulating terrain never quite destroys you.

Start/End // Stanley, Tasmania

Distance // 15–63 miles (25–101km)

More info // www.gonenuts.com.au

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

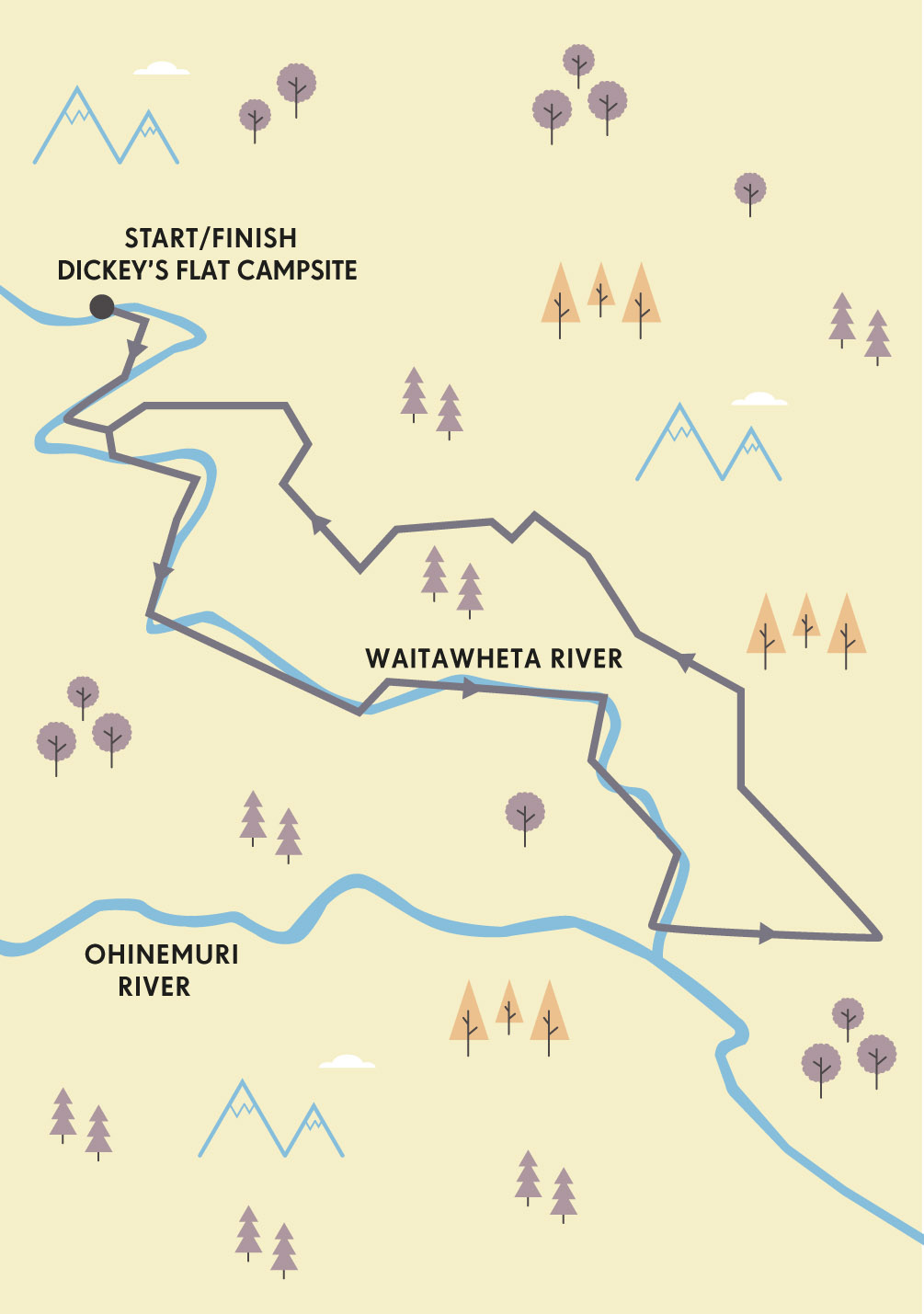

THE GHOST RUN OF WAIHI GORGE

You’ll have plenty of companions as you navigate the mine-scarred mountainsides of New Zealand’s Waihi Gorge – you just may not be able to see them.

I have run all over New Zealand and still only found one place where I need my headtorch during the day: Waihi Gorge in the North Island. Hugging the sides of a steep narrow cut in the earth, the trail passes through a network of tunnels carved out by gold-mining lust. The mines can be explored during an undulating 6-mile (10km) loop that circumnavigates a canyon dripping with history and unsurpassed natural beauty. And it’s the prospect of a supernatural sighting that has always made this run one of my favourites.

The town of Waihi is a two-hour drive south of Auckland, within easy reach of Rotorua and Taupo. Gold was discovered here in the early 1800s and, by 1908, it was the fastest-growing town in New Zealand. Luckily for the trail runners and hikers who converge here these days, the same catastrophic geological upheaval that brought precious minerals closer to the earth’s surface also created dramatic mountains and ravines. Most tourists are content with a short stroll around the close to the car park. But one must venture beyond the interpretation panels to really feel the sense of history and, possibly, commune with the gorge’s former residents. At one point these ravines were home-and-income to more than 2000 people living in straggly buildings that clung precariously to the sheer rock walls. No one lives here now, and the stillness is haunting.

Meanwhile, Waihi itself is lively, with a plethora of accommodation. Yet, for me, the Department of Conservation campground at Dickey’s Flat is always basecamp. Waking up here, I take the luxury of a leisurely breakfast in the warm spring sunshine before donning my running shoes and pack.

The first few hundred yards loosen me up, as I bounce across the first of many single-file wooden suspension bridges along the route. Crown Track stretches before me, flickering in and out of the sun as patches of cool, damp forest alternate with small clearings of flax and grass. The trail is wide, flat and well-graded, and I relish the sense of flow, as I skim along beside the Waitawheta River.

© John Bentley | Alamy Stock Photo

nearby Karangahake Gorge

But sunshine and birdsong quickly disappear as the trail climbs gently above the river, which has now swollen to a deep, fast torrent. The trail is littered with tools and machinery abandoned a century ago. A set of stairs takes me higher above the river and my excitement builds as a tunnel signals the start of the Windows Walk.

Donning my headtorch, I step cautiously into the gloom. What men these were, grubbing at the dank walls for 16 hours a day, inching deeper and deeper into the mountains in search of sparkles in the bleak rock. Miners desperate to escape this hell were known to sever their own thumbs to be relieved of duty, and the Waihi Museum contains rows of human digits preserved in jars.

The rock-strewn tunnel floor makes for slow going and I am beginning to shiver when I see thin rays of natural light seeping in from the first window. Leaning on the rough-hewn sill, I stare straight down into the thrashing Waitawheta River. I continue, bypassing a handful of windows before popping out into bright sunlight and clear running again. More tunnels follow: these are shorter, allowing me to stash the headtorch and forge on in the darkness. As i jog carefully along a disused tramway, an abandoned railway wagon makes for fun photography.

“More tunnels follow, but these are shorter, allowing me to stash my headtorch and forge on in the darkness”

A short flight of stairs deposits me rather abruptly into a large clearing and a dramatic landscape – the tumultuous confluence of the roaring Waitawheta and Ohinemuri Rivers. At approximately three miles in, this marks the apex of my loop. And to this point the route has not been all that taxing. There are several options in front of me: tracing the right bank of the Ohinemuri River, the Karangahake Historic Walkway extends four miles past Owharoa Falls to the fascinating remains of Victoria Battery. Alternatively, a few hundred metres along the Walkway, a half-mile-long disused railway tunnel and an open double-level truss bridge make for a terrifically fun loop.

Today, however, I long for the trees so decide to follow the western side of the gorge – a very different experience to the relatively easy running of the morning. I brace myself for a sharp climb up through the damp tree-lined Scotsman’s Gully. My legs feel fresh and the road hums smoothly by. County Rd slowly ascends Karangahake Mountain and I become conscious of a different age of industry. The Kaimai Ranges were logged heavily in the 1800s for native kauri trees. These forest giants live for well over 600 years, attaining girths up to 5m in diameter.

Gravel soon peters out and I am back on forested single-track. The trees touch overhead and birds click and squawk in the canopy. Silver fern is abundant, recognised the world over as the emblem of the New Zealand All Blacks rugby team. As the trail continues to wind around the face of Karangahake Mountain, I catch the occasional vertiginous glimpse down the rock face into the depths of the canyon. It is always surprising how much height is gained on this leg, as the running is smooth and uncomplicated.

© Gina Guarnieri | Getty Images

NZ’s famous silver fern

PUMPHOUSE PRESERVATION

Waihi’s Pumphouse was built in 1904 to house steam pumps for the deepening Martha Mine. When electricity rendered the machinery redundant in 1914, the equipment was removed and the building declared a historic monument.

In 2004, engineers discovered the ground was too unstable because of the underground mines. So Teflon-coated concrete beams were used to slide the three-storey 1,840 tonne icon 300m to where it currently resides.

© John Bentley | Alamy Stock Photo

river crossings made easy

But now I have reached the final junction, and excitement bubbles up in me again. The main track continues onwards and upwards towards the mountain’s summit. Instead, I break left to access the rollercoaster ride affectionately known as ‘Dubbo’s’. Dubbo 96 Track is steep and soft, true singletrack at its best. I am grinning inanely as I hurtle downwards, placing faith in my feet to find solid contact at each lunge. Tall broadleaf and podocarps filter out much of the sunlight, creating an atmosphere of delicious mystery. I marvel at how quickly the ascent I worked for is lost.

Bottoming out at a cold, clear stream, the trail climbs sharply over a small quad-destroying ridge before finally spitting me back onto wide, sunny Crown Track, where the journey began. Cooling down on the final flat stretch back to Dickey’s Flat, I pause on the last bridge to gaze into the quietly moving river. It has been an evocative jaunt, and I wonder whether the miners and loggers also paused in their trudge back to camp at the end of an arduous day, arrested by the majesty of the mighty Karangahake. I would like to think so. VW

© Paul Abbitt rml | Alamy Stock Photo

old railway tunnels-turned-footpaths

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Dickey’s Flat Campsite

Distance // 6.25-mile (10km) loop

Getting there // Karangahake Gorge is 140km (a 2-hour drive) south of Auckland; 130km north of Rotorua.

When to go // Year-round, but the tracks may be closed by rockfall or flooding in inclement weather.

Where to stay // Basic camping is available at Dickey’s Flat, or there are several motels in Waihi or the nearby resort of Waihi Beach.

More info // www.doc.govt.nz/karangahake

Things to know // Bring a headtorch for the tunnels, light thermals in colder months, and check the Department of Conservation website for track closures before you go.

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

NEW ZEALAND TRAIL RUNS

MT PIRONGIA

Lying in slumber just 15 miles (25km) from the Tasman Sea, Mt Pirongia reclines gracefully like a sleeping woman. Be warned, however, this extinct volcano, with her numerous basalt cones, is certainly no lady. Rising dramatically to a height of 3150ft (960m) above the Waikato plains, the summit is known for notoriously fickle weather that is prone to rapid deterioration. There are steep and treacherous drop-offs, slippery rocks to clamber over and the trails can be extremely muddy at any time of year. Steel yourself for a challenge – plan and prepare well, take warm and dry gear, and be prepared to travel slowly at times. In return, those who run Pirongia are rewarded with rare flora and fauna, impressive views and some of the most technical running to be had in New Zealand.

Start/End // Grey Road car park

Distance // 7.4-mile (12km) loop via Tirohanga and Mahaukura tracks

More info // www.doc.govt.nz/

THE PINNACLES

Testimony to its appeal, a day-trip to the Pinnacles is on the official ‘101 Must-Do’ list for New Zealanders. The main track traces the original route taken by packhorses to carry supplies to kauri loggers and gold-diggers in the early 1900s, climbing through stunning native forest and crossing numerous small streams. The trail continues past the hut before climbing to the Pinnacles themselves – a good head for heights and confident footing is required to make the final climb up these rocky spires. A popular location to view sunrise and sunset, the Pinnacles command panoramic views of the Coromandel Peninsula, Hauraki Gulf and Kauaeranga Valley. Escape the crowds by returning via historic Billygoat Track, dotted with rusting machinery left abandoned by retreating loggers and miners.

Start/End // Kauaeranga Valley road-end

Distance // 12.4-mile (20km) loop via Pinnacles and Billygoat tracks

More info // www.wildthings.club/trails/

WAIRERE FALLS

If hills provide the motivation to get you out of bed early, the climb to Wairere Falls is a great way to bank some vertical miles. Somewhat dramatically, the Wairere River slides off a wide, rocky shelf at the southwest end of the Kaimai Ranges to tumble down 500ft (153m) to the plains of Te Aroha. The rock shelf is a popular spot for summer bathers, but extreme care must be taken during periods of heavy rainfall, when the Falls can double in volume. This short out-and-back route delivers 1900ft (580m) of elevation in just over two miles, with an equally quad-thrashing descent – exercise caution on slippery rocks and wooden stairs. Above the Falls it is possible to access other trails that lead deeper into the southern Kaimai Ranges.

Start/End // Goodwin Rd (off Old Te Aroha Rd)

Distance // 4.3 miles (7km)

More info // www.wildthings.club/trails/

© Julian Wyth | Alamy Stock Photo

Wairere Falls tumbles 500ft (153m), with fun running trails near the top and bottom

- EPIC RUNS OF THE WORLD -

A TOUR OF TASMANIA’S FREYCINET PENINSULA

This devilishly delightful trail run covers it all, from the high ground of the Hazards to the pinot grigio-clear waters of Wineglass Bay.

The best runs are often the ones you never intended doing. Whether sublime, unscripted scrambles or even flat out mistakes, it’s these accidental adventures that live on in the memory, long after leg muscles have forgotten the extra miles. At least, this is what I told myself as an intended quick loop around one little corner of Tasmania’s Freycinet National Park – a sub-seven-miler from Parsons Cove to Wineglass Bay, via Hazards Beach and the Isthmus Track – mistakenly morphed into a nearly 19-mile (30km) circuit around the peninsula.

I’d always wanted to do this route at some point. Although it’s rare to see another runner on normal days (we’re well outnumbered by walkers), the full Freycinet Circuit is talked about in language of awe by trailhounds who have taken it on. It’s even run as a race every July. Neatly knitting together a network of cracking paths to traverse granite peaks, brilliant white beaches and thick coastal forests, it’s a route that every visiting runner wants to experience. But it wasn’t part of the plan that day – I had a plane to catch.

© Visual Collective | Shutterstock

Tasmania’s famous Wineglass Bay

“At Wineglass Bay it was impossible not to cast off my kit, streak across the squeaky white sand and plunge into the ocean”

I was on Australia’s Apple Isle for reasons far removed from running, but the thought of leaving without at least a cursory explorative flit around Freycinet felt criminal. So, setting off from the trailhead at first light, I trotted along the flat Hazards Beach Track, skirted Great Oyster Bay from Parsons Cove and curled around the ankles of Mt Mayson. Mayson is one of four peaks (along with Mt Amos, Mt Dove and Mt Parsons) collectively known as the Hazards, which stand sentinel across the peninsula’s delicate neck. Warming to my mission I picked up the pace, as thoughts of Tasmania’s past chased me along the path.

For millennia, the indigenous Toorernomairremener people had this place to themselves, leaving middens made from oyster shells as the only enduring evidence of their existence – an existence immediately threatened when European sails appeared on the horizon. A Dutch explorer left his mark on the map in the naming of Freycinet, but it was the Brits who first found a use for this faraway land.

© Karel Stipek | Shutterstock

Hazards Beach treasures

It seems utterly inconceivable now, but this stunning spot was once a dumping ground for Georgian society’s undesirables – a place where unimaginable horrors were inflicted on hundreds of unwanted humans. Infamous penal colonies were established nearby, at Port Arthur and Maria Island, and convict labour was used to develop Freycinet, a delicate finger of land pointing into the Tasman Sea. Ironically, thousands of Poms now pay good money to come here.

© Jochen Schlenker | Shutterstock

Great Oyster Bay

Rising over a spur, a sudden movement shook me back to the present. I whispered an apology to the red-necked wallaby I’d rudely disturbed. A joey lay awkwardly in her pouch, legs and arms jutting out either side of a cheeky head, as it nonchalantly nibbled dewy grass at the track’s edge.

The Hazards’ peaks protected me from the glare of the rapidly rising sun, casting the trail in cool shadow. No need to worry about stepping on any sleepy tiger snakes just yet, they were all busy breakfasting in the bush between the she-oaks, and wouldn’t start sunbathing on the tracks until later in the day.

Passing Fleurieu Point and Lemana Lookout, where the view is full of Promise Bay, I hit the golden ground of Hazards Beach about 2.5 miles (4km) into the run. I instinctively veered towards the hard-packed sand left behind by the retreating tide, and it was here, bamboozled by the beauty of the beach, that I ran right past the sand ladder leading up to the track that shortcuts across the isthmus to the northern end of Wineglass Bay.

I only realised my mistake on reaching Lagunta Creek, at the end of the 2-mile-long beach. But my leg muscles were well warmed and I decided to crack on through the eucalypt forest towards Cooks Beach. By now I was fully committed. My map indicated it would almost be as far to run back as it would be to carry on, and a desire to keep exploring blinded me to the contour lines that revealed a big climb just ahead.

© Christian Musat | Shutterstock

a female rednecked wallaby with her precious cargo

The track then veered inland, rounding Mt Freycinet. Refilling my hydration pack from Botanical Creek, I ascended the flanks of 1900ft (579m) Mt Graham. Crossing East Freycinet saddle, now nearly 10 miles (16km) into the run, and with my quads quarrelling with my brain, I climbed the spine of the peninsula, picking a route through boulders as I battled a crosswind.

The view and the cool breeze easily compensated for the climb. Wonderful Wineglass Bay winked from below; beyond that, the cliffs of Mt Dove dove down into an azure ocean. Scrambling onwards, I crossed a woody plateau and dropped through a gully towards Graham Creek, then traced Lone Rock Ridge down to the southern end of Wineglass Bay, where a crescent of bright white sand cups the translucent Tasman Sea. Confronted by the most beautiful beach I’ve ever set foot on, completely devoid of human company, it was impossible not to cast off my kit, streak across the squeaky-fine sand and plunge into the ocean. Still dripping, I traced the track back to the trailhead, crossing the saddle between Mt Mayson and Mt Amos to Parsons Cove.