1

MAY 13, 1940

DINANT, BELGIUM

1600 HOURS

General Erwin Rommel has had a very busy weekend.

The Meuse River rages fast and cold. The loyal admirer of Adolf Hitler paddles a small rubber assault raft toward the west shore. Locals blew the bridges one day ago. This exposed crossing is the only way. Rommel and the young Wehrmacht soldiers spilling over the sides of the cramped black inflatable are not alone. All around them, German troops dig their paddles into the green current, desperate to reach the far shore, where heavily fortified French troops lay down thick rounds of fire.

“On the steep west bank . . . the enemy had numerous carefully placed machine-gun and anti-tank nests as well as observation points, each one of which would have to be taken on in the fight,” Rommel will report. “They also had both light and heavy artillery, accurate and mobile.”

Some French defenders are hidden in concrete bunkers on the high rocky bluffs, while others aim their M29 machine guns out the windows of abandoned homes on the water’s edge. Still other French fighters launch heavy artillery from the ruins of the Crèvecoeur Castle, near a mighty bend in the river where spotters have a clear view of the German attackers.

For the first time in days, at a time when he needs it most, the wiry, forty-eight-year-old Rommel enjoys little air support. The only covering fire for the general and this band of young infantry soldiers from the 7th Rifle Regiment—almost all less than half his age—comes from the shore behind them, as tanks from his 7th Panzer Division unleash lethal rounds at French positions.

Yet the Meuse must be crossed.

Wehrmacht troops have been practicing this moment for months on the Mosel River in the secrecy of Germany’s Black Forest, with Rommel in particular driving his men hard to perfect their crossing tactics. This is his first tank command after a highly decorated infantry career and he is desperate to succeed. The time has now come to put that training to use.

One hundred yards wide at the Leffe crossing point, and fast enough that any man or vehicle attempting to ford its waters will be swept away, the meandering Meuse is a daunting geographical blockade between the rugged Ardennes Forest and open countryside leading straight into France’s heart and soul: the capital city of Paris.

The two-thousand-year-old city on the banks of the Seine River is the most sublime and resplendent city in Europe. The City of Lights, as Paris is known, is famous for its architecture and museums, thinkers and writers, ideals and poetry, cuisine and history. As King Francis I, former ruler of France, once stated: “Paris is not a city; it is a world.”

Such is the allure that Germany’s despotic supreme leader, Adolf Hitler, once an aspiring painter of watercolors, has a long-standing fascination with Paris’s beauty. Hitler has never set foot in the City of Lights, but despite his admiration he still seethes about the punitive terms of surrender France imposed on Germany at the end of World War I. The Führer is determined to conquer Paris and humiliate its citizens with a display of total Nazi power.

“When at last,” Hitler wrote in his manifesto, Mein Kampf, “the will-to-live of the German nation, instead of continuing to be wasted away in purely passive defence, can be summoned together for a final, active showdown with France, and thrown into this last decisive battle with the very highest objective for Germany; then, and only then, will it be possible to bring to a close the perpetual and so fruitless struggle between ourselves and France.”

Hitler dreams of oversized German flags bearing the swastika, symbol of his National Socialist—“Nazi”—Party, flying from the Eiffel Tower. In this fantasy, museums like the great Louvre will be looted and priceless works of art shipped to his own capital city of Berlin, which will be redesigned and reconstructed, completing his goal of humbling the French even further by ensuring that Berlin’s wonders far outstrip those of Paris.

Adolf Hitler is very close to realizing that dream.

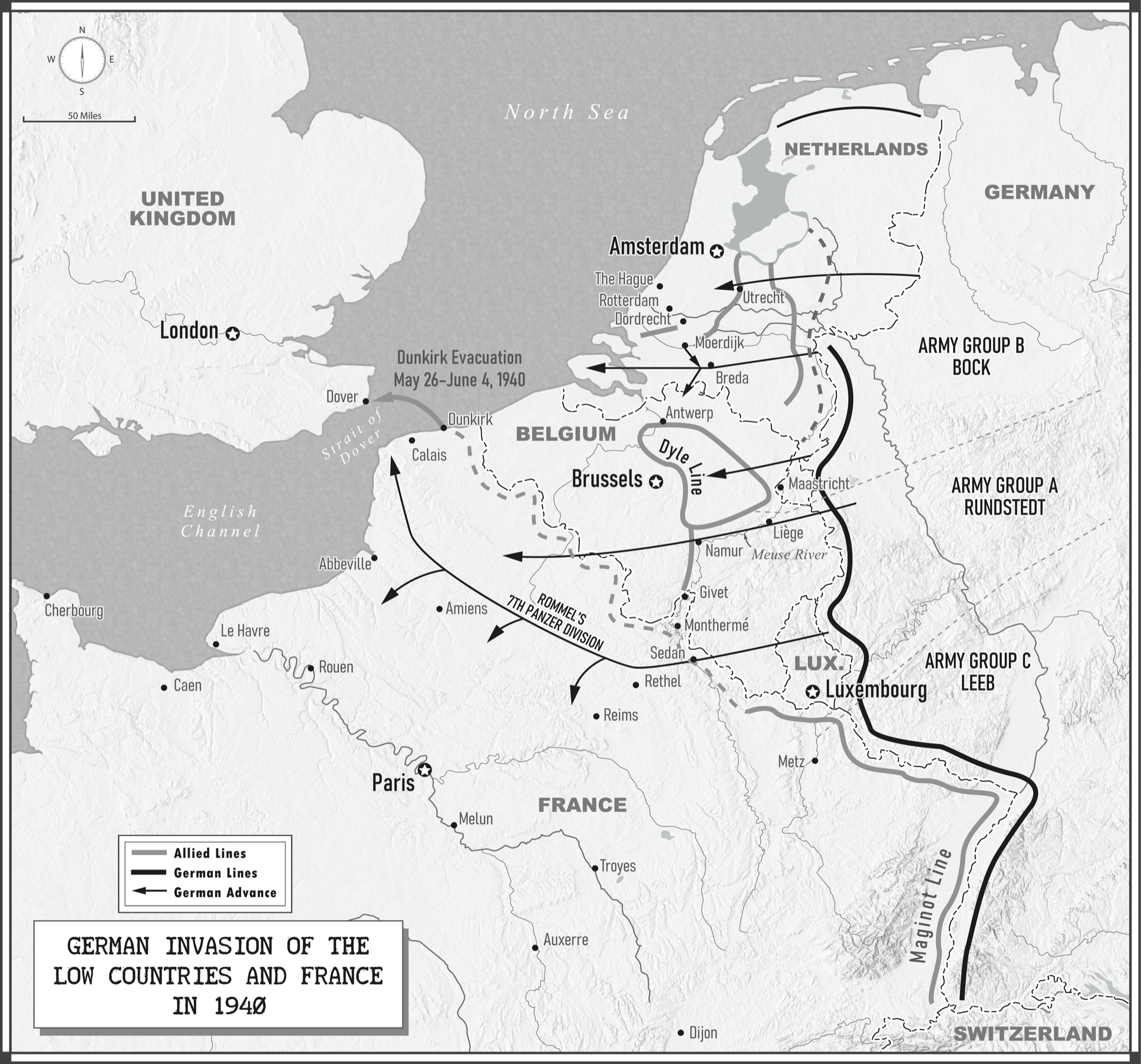

The battle for France began on May 10, just three days ago. More than a million German soldiers poured across their border, determined to crush the French army and its British ally, which has sent nearly a half million troops to aid in the defense. Utilizing a technique known as blitzkrieg—“lightning war”—combining fast-moving divisions of Germany’s ten panzer tank divisions accompanied by fighter planes and dive-bombers in the skies above, Hitler’s unstoppable forces are attacking with a speed never before seen in warfare. It is the panzers at the forefront, punching through enemy defenses and using speed to expand the fluid battle lines. They do not wait for the infantry, as is the tactic of French tanks. Wehrmacht foot soldiers simply do their best to keep up.

The German forces are split into tactical armies, with German Army Group B spearheading the attack in the north. Their mission is to slice through Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands, not only capturing those nations but also luring British and French troops into battle. Unbeknownst to the Allies, this is a fatal trap.

Meanwhile, German Army Group A silently approaches from the east, using the dense Ardennes Forest to conceal what will become known as one of history’s greatest surprise attacks. Their job is to dash all the way from the German border to the English Channel, then link up with Army Group B to completely surround and annihilate the Allied forces. Known as a “double envelopment,” this tactic is among the oldest in military history, used by Hannibal to defeat the Romans at Cannae in 216 BC. On paper, it looks like two sides of a vise pressing together, squeezing the conquered army in between. If successful, Hitler will accept the French surrender in due course, then have Paris and all of France to call his own.

But the bold plan will fail if German Army Group A cannot cross the impregnable Meuse. Flowing 575 miles from northeast France all the way to the North Sea, this serpentine river twists through valleys lined with high cliffs. “Mosa,” its Latin name, roughly translates as “maze,” for the many abrupt bends and U-turns on the waterway’s journey to the sea.

And it is not just the Meuse that serves as a natural barrier between Germany and France but also the mountainous terrain on both banks, making for impregnable natural defensive positions.

France’s top military leader, the intellectual General Maurice-Gustave Gamelin, has every confidence the Meuse will stop the German invasion. He is the architect of “stand-and-take-it warfare,” as some in the press label his strategic mindset.* The white haired Parisian calls the river “Europe’s best tank obstacle” and has planned his battle strategy accordingly. “La Meuse est infranchissable”—“The Meuse cannot be crossed”—the general is fond of stating. In 1939, Time magazine named Gamelin “the world’s foremost soldier,” almost ensuring that those words are treated as gospel.

But just ten days before Germany attacked, a French military attaché in Switzerland passed along intelligence to General Gamelin in Paris stating that the Germans would invade through the Ardennes Forest, then attempt to cross the Meuse. The attaché was ignored. Gamelin’s belief in the invulnerability of the Ardennes is so profound that he also rejected a 1938 study by his own commanders stating that not only will an attack through the forest succeed but German troops will race to the Meuse River within sixty hours.

In fact, Rommel’s panzers need just fifty-seven.*