Chapter 8

Social Innovation

Doing good is not exclusive to graphic design; every profession wants to influence or bring about positive change. In recent years, the term “social innovation” has become part of designer jargon. It is not entirely specious: Designers routinely make innovations for social welfare. Like any buzzword (e.g., design thinking), its effectiveness diminishes with overuse. Still, for our purposes, terms like “social impact” and “social innovation” serve the same yet broader function than “pro bono” (which is often thought to mean “free work” but is actually derived from pro bono publico–”for the public good”–in Latin).

Social innovation can be a career path or not. It can be a means to build a portfolio or not. It should be a way to help others directly or indirectly. Graphic designers have long been seen as those who support social innovators through the expert organization of useful data or the rebranding of a not-for-profit organization. Yet graphic designers are finding ways to take an even more proactive role as “makers” and “producers” of socially valuable products. Here the term “social entrepreneur” is apt, for designers with easy access to digital tools are equipped to make significant contributions. This chapter will not provide the outlets you need to make a difference, but our interviews address the ways to find those outlets and to channel your inspiration for the public good.

Mark Randall

The Citizen Designer

Logo for Worldstudio Foundation's Signature Program:

Design Ignites Change.

Designer: Worldstudio

Worldstudio is a unique business model. So much of your work is in the area of social good. Please explain how this works.

Our goal was to create a studio that not only served clients but [was] one that would give us a platform to develop our own self-generated projects and programs around the social issues in which we were interested. There are two parts to the organization: Worldstudio, Inc., the for-profit side, and Worldstudio Foundation, which is nonprofit. We actually started the foundation first and then launched the design studio two years later. Because of tax requirements, we needed two organizations–but in the end, we think of them as one, just Worldstudio.

Worldstudio, Inc. works like most traditional graphic design firms that offer client services, but our focus is on the nonprofit and civic realm. Working in this area supports our mission of using design to impact positive social change. We work on a wide range of projects from branding, interactive, and collateral to packaging and environmental graphics. This side of the business pays my rent and allows me to buy tickets to the most recent Star Trek movie.

Why did you launch a foundation? What was your aim and goal?

We established Worldstudio Foundation as a tax-exempt, 501c3 organization to create the social initiatives that we wanted to develop. We needed the tax benefits of being a nonprofit so that we could accept donations and receive grant money from our partners, which is how we fund these initiatives.

Identity and Package Design for a Socially Minded Tea Company That Focuses on the Triple Bottom Line:

Profit, People, Planet

Designer: Worldstudio

Photographer: Mark Randall

We believe that creativity holds enormous power for positive social change. Through the work of the Foundation, we focus our efforts on providing inspiration and support for designers, architects, and artists who want to use creativity to give back to their communities and the world at large. Our initiatives have ranged from scholarship programs, professional fellowships, and grant making to educational opportunities, which include mentoring programs for high school students and social design workshops and intensives for college students and creative professionals. We have created a number of high- visibility public art and design projects, which unite communities around compelling social themes.

How much of what you do is strategizing for meaningful projects and actually designing?

Strategizing around a meaningful project is the best part of my job–but, alas, it is a small part. We're a small office; right now it's myself, two designers, and our foundation programs director. Everyone has to do a little bit of everything. My day-to-day responsibilities break down in two ways: For Worldstudio, Inc., I act as art director and client liaison. I usually have a range of disparate activities going on at the same time; because of this, I find it hard to carve out chunks of time in which to focus on the actual process of design. But when I do, I enjoy it. When it comes to our social initiatives, my role is that of a producer, developing the concept, building the strategy and partnerships needed to make it happen, and then managing the project through to completion. We believe in the power of partnerships, and everything we do through the Foundation is very partner driven; these relationships are critical to our success.

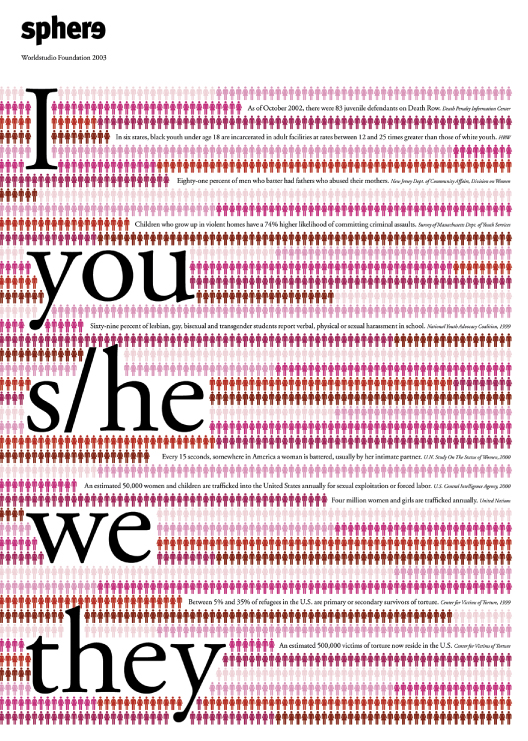

2003 Issue of Sphere on the Theme of “Tolerance”

Editorial and Creative Directors: Mark Randall, David Sterling

Editors: Peter Hall, Emmy Kondo

Designer: Daniela Koenn

Cover Designer: Santiago Piedrafita

Talk about your favorite (and possibly most successful) project.

Drawing on my vast experience as the publisher of Star Charting, our first social initiative, in 1994, was a magazine called Sphere, which featured articles about artists and designers who incorporated a social agenda into their work. At the time, there was little to no discussion around design and social impact in the media. We decided that a publication would be a great venue in which to explore these ideas and generate a conversation around the subject.

Sphere, “Wish You Were Here” Issue

Editorial and Creative Directors: Mark Randall, David Sterling

Editors: Peter Hall, Emmy Kondo

Designer: Sven Oberstein

Cover Designer: Shawn Wolfe

We not only acted as the publisher, but we were the editorial and creative directors as well, bringing together teams of editors, writers, and designers for each issue. We produced seven issues over nine years, and each issue was sent free to 15,000 designers across the country.

Urban Forest Project Lightpole and Banner Tote Bag

Designer: Rob Alexander

Client: Jack Spade

Photographer: Mark Dye

That sounds quite ambitious. . .

Sphere demonstrated to us that we could launch our own initiative and make it economically viable. This also gave us visibility and street-cred in the design community, which we built upon for future opportunities. I think of Sphere as the foundation of our Foundation.

What do you look for when hiring someone to work at the studio or on specific projects?

For Worldstudio, Inc., a designer with excellent communication and typographic skills is critical. I am not interested in just aesthetics. I get excited when I see a combination of inventive creativity–which can be very cutting-edge and contemporary–mixed with clear and compelling communication. I like design that is playful and fun with the right note of seriousness when the message calls for it.

On the Foundation side, we look for creative individuals, often who come from a background in arts administration. They don't have to be designers, but they must have an interest in design and how it relates to social issues. This is a rare combination, but we have been lucky and have had great people working with us.

You not only run Worldstudio but also you direct a summer intensive, Impact! What is your goal here?

The profession as a whole is trying to figure it out. We need to create our own opportunities to work in this area and demonstrate to potential employers, clients, or collaborators what we can bring to the table. Recent graduates as well as midcareer designers are looking for ways in which to pursue this type of work. There are not many opportunities for designers to learn about this emerging field, and there is no go-to list of social design jobs to apply for.

We launched Impact! in the summer of 2010 to give people a place to start, as well as an understanding of the field. We like to think of our program as graduate school crammed into six weeks. Many of our students have leveraged their Impact! experience into a full-time social design job or they have gone on to launch a business or project idea they incubated in the program.

In the not-for-profit world, is it possible to sustain oneself financially?

Socially minded work is not limited to the nonprofit world. There are a range of opportunities out there–all of which require research and perseverance to unearth. I see them breaking down broadly into the following categories.

You can get a job working for a nonprofit organization. Many mid-to-large-sized foundations have their own in-house design departments. Currently, foundations utilize graphic designers in the traditional way: to create their communication materials. I am optimistic about a future where these organizations will see the value of having a designer at the table as they develop the initial strategy around their programming. Designers should be more involved in the entire process, not just as an add-on at the end to make things look better.

Corporations have money, reach, and power; many are engaged in corporate social responsibility (often referred to as CSR), recognizing that it directly affects their bottom line. They need designers to help them communicate their efforts. As with nonprofits, I'd like to see a future where we are at the table from the beginning to help with strategy. Our skills as creative problem solvers can be brought to bear, and we can work from within, as entrepreneurs, to help them make meaningful change. This may be overly optimistic–but a worthy goal!

Ringling Museum of Art Identity

Client: John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida

Designer: Worldstudio

Icon designer: John Pirman

Government desperately needs good design. This is an area full of opportunity, as it gives designers a chance to work on projects that impact the lives of millions of people. Right now it is an uphill battle but I believe one that is worth waging.

If you want to start your own design firm, you can create a client base from a segment or mix of all of the above. There are successful studios that do this. Granted, it might not be as lucrative as a client list made up of Fortune 500 companies, but from my personal perspective, working for social change trumps the money.

Lastly, you can live the life of a social entrepreneur and create your own socially minded nonprofit organization or social enterprise. This is the area that expands the most on what designers can do. Design is often not the end result, but the skills of a designer are brought to bear on making the concept reality.

Is there a business model for being a “pro bono” designer?

I have mixed feelings about pro bono work. We should get paid for the work we do, even if the work is socially motivated. Pro bono is not sustainable if you want to engage in this type of work over the long term.

One business model that is often cited is to take a percentage of your time, ranging from 1 to10 percent, and dedicate it to pro bono work. Based on a 40-hour work week, 1 percent represents a modest 20 hours per year per person, and 10 percent represents 200. It is important to treat pro bono work just as you would a paying client. Create a proposal with a clearly defined scope of work, outlining expectations on both sides. And, sign the contract!

I don't believe that you should do pro bono work without getting something in return: deep personal satisfaction, an opportunity to learn a new skill, introductions to a new community, or a great piece for your portfolio that you can leverage for future opportunities. I allocate my pro bono services to my own efforts through the Foundation, and I can easily say that I get a return on this investment from all of the benefits I just outlined.

Bob McKinnon

Socially Impactful Design

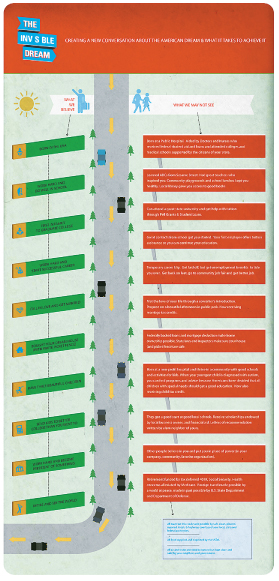

Invisible Dream

Client: GALEWiLL Center for Opportunity & Progress

Studio: GALEWiLL Design

Designers: Bob Mckinnon, Tyler Mintz

What is your definition of social innovation in today's design scheme?

I see social innovation as anything we create or design that can move the world forward. It can be for one person, one community, or the entire planet. “Does this make someone's life better?” is a simple question we should always ask ourselves when designing anything. If the answer is “no,” we should respond by wondering whether we should be doing it at all. If the answer is “yes,” then we should think about how to get this out to more people who could benefit by it.

What is different in today's design world than 10 years earlier regarding design for social good?

Ten years ago, design for social good was less an explicit goal and more of an implicit choice. Even then, within almost any design choice we make, we could either move the world forward or set it back–in ways imperceptible or grand. Today things are much more open and accessible. There are more opportunities to explicitly focus on this kind of work. Firms such as ours do 100 percent social change work. Others open up smaller practices within larger organizations. Platforms and tools come on the scene that promote social entrepreneurship and make it more attractive. The explosion of opportunities in this space has been incredible and much welcomed.

How should designers get involved with public welfare projects?

In some ways, we create a false choice when we position public welfare projects vs. commercial projects. Everything we design has the potential for social impact, regardless of whether it's designing for a public cause or making better choices for a company.

Practically speaking, there are more entries into this space than ever before. You could tackle a cause you believe in on your own, volunteer for a small nonprofit, get an advanced degree in design for social impact, work for a company you believe d oes good things for the world, even go into government. There is more and more demand for people with great design skills and a passion for making a difference.

Is this still called “pro bono”–the occasional free job–or have we reached the point where this kind of work is not the exception but the norm?

I think we've reached the point where pro bono is becoming less and less the norm, and I think that's a good thing.

We pay for things we value. And what is more valuable than designing something that could solve major societal issues and improve lives? There is a unique skill set that comes with designing for social change. And like any other field within design, extensive experience and knowledge command a premium.

Now, of course, if you're a small nonprofit with limited resources and there is a designer looking to contribute who is passionate about that cause, then this can be a match made in heaven.

But, alternatively, if you have large organizations with significant resources that are trying to tackle critical issues, then they should pay for expertise. This is no different than what you would do if you were hiring an engineer or architect to build your headquarters, an accountant to do your finances, or a lawyer to manage your legal issues. Design for good shouldn't be charity work, unless it absolutely has to be.

How are social impact jobs solicited and funded?

The good news is that increasingly people are seeing the real value good design can bring to a cause. It can be the difference between whether an organization fails or succeeds or whether one life is saved or a million. So within organizations, you can begin to see the return on investment that comes with good design.

More and more organizations are making investments in this space, and I think there will be increased demand for talent as a result. The White House has an Office of Social Innovation and Civic Participation. There are media outlets like Good and Fast Co-Exist that increasingly feature design for social good. Schools like SVA create stand-alone programs to meet the increasing demand. Large foundations and nonprofits are increasingly investing in design for themselves and their partners. And this is to say nothing of the people who are creating viable businesses, like Tom's Shoes, who are proving that doing good and making money don't have to be mutually exclusive pursuits.

Redesigning California's Food Stamp Program

Client: California Department of Social Services

Studio: GALEWiLL Design

Designers: Bob Mckinnon, Jennifer Kaye

What should a designer do to make a viable project?

Start by designing for one. We can fall into the trap of “I want to change the world” and forget that this still happens at the individual level. What does one person need to improve their lot in life? I love to talk to social entrepreneurs about their origin stories–what was their inspiration for getting started. Almost without exception, they tell me a very simple yet instructive story about how they were looking to help one person. Whether that's Sal Khan whose Khan Academy began by tutoring his cousin Nadia or Adam Braun who started Pencils of Promise as the result of an interaction with a child while he was traveling, it always starts there. If you want to change the world, design for one.

At the same time, we must remember that a person's life is not a problem for you to solve. We make the mistake of designing down, thinking we know what people need. We should design up, first seeing if we can be of some help, asking them how and letting them be the agent of their own success.