Chapter 9

Branding and Packaging

Branding is storytelling. “It's that simple,” Brian Collins said in the previous edition. “And storytelling is always interesting because it's driven by one question: What happens next?” That's what consumers want to learn. It's why they turn the page, why they enter a store, or click online—to see what happens next. The anticipation of being drawn into a new world or experience guides us all. Collins adds: “We are all in the what-happens-next business.” People lose interest, fast, when nothing interesting happens next. So branding people—designers and writers—evolve stories to retain the public's interest. It is the job of advertising and design to help shape brand stories into something truthful, meaningful, and useful. When branding is done with sincerity and imagination, the outcome can be beneficial to the corporation and the individual. Design is a tangible, immediate kind of storytelling because it touches people's actual experience. “It isn't the promise of experience—like an ad,” Collins notes. It is experience.” Design is a brand's promise made visible, and ultimately, personal. And once an experience becomes personal, it can become a meaningful part of someone's own story.

Take the example of pirates and their skull and crossbones flags. That black flag—the logo—was the pirate brand identity, and it sent an unmistakable brand promise to other ships and sailors. The flag prompted distinct brand expectations, which if you believe the movies, the pirates consistently delivered. “Each time they acted ruthlessly,” Collins says, “the pirates delivered on their brand promise—and deposited more legends and meaning into their flag. In fact, they were so bloodthirsty so consistently that by the eighteenth century, all a pirate ship had to do was hoist its Jolly Roger and the crew of the victim ship would often drop their cargo and flee.”

Designers today are principal participants in the branding business. This means going beyond the design of one-off artifacts and creating as much of that broader experience as they can. If you are asked to design a package, for example, try to create such a big idea—a big story—that it could inspire the design of a great store, an ad campaign, a film, an event, a game, or a series of books, all based on the product idea. That is the branding idea.

Sharon Werner

Approachable Design

X.ALE Wet Orange Drink

Designer: Sharon Werner

How did you come to define your field of expertise?

This has not been a planned path, but, rather, one project led to another and to another. We don't call ourselves experts in any specific category, but, rather, we are observant, curious, intuitive consumers and observers. This curiosity has led to projects in the wine and spirits industry, fashion, [and] children's and personal care products, to name few.

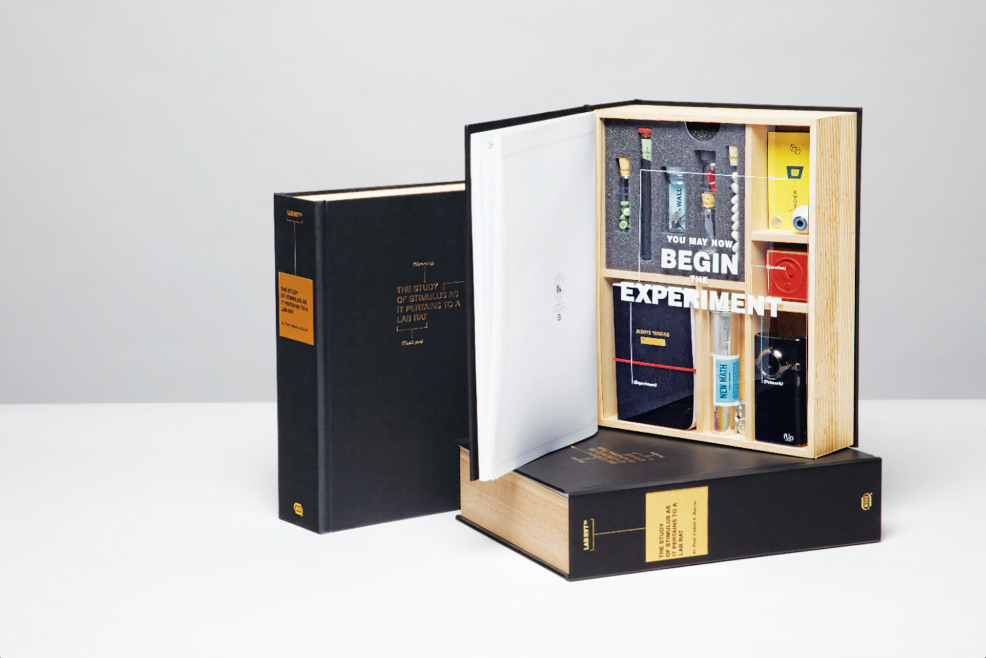

Labrats Work Kits

Designers: Sharon Werner and Sara Forss

How are Sarah Forss, your senior designer, and yourself are able to share the workload so seamlessly?

Sarah and I have worked together for over 18 years. Maybe that answers the question best. Basically, we have a process that works well for us. We share most projects in the beginning phases. We're open to criticism from each other and don't feel overly protective of our ideas. We can see potential opportunities or pitfalls in each other's rough sketches.

At some point in the process, one of us takes the lead, and the other becomes supportive. This can flip back and forth throughout the project. We each grow very familiar with the broad overview and fine details of the projects. At the end, it's often difficult to remember exactly whose original idea it was.

Part of your philosophy is to enter into a collaborative relationship with clients. But that's dangerous, isn't it?

Do you sometimes have to “crack the whip” and let them know that, as far as design is concerned, you are in charge? Now more than ever, clients want to be part of the process. Dangerous?

Yes, definitely! But it's a reality, or at least it is for us. Many of our clients are financial stakeholders in the project. They want to see the process at multiple points in order to protect their investments. I can't say I blame them.

dp Hue Shampoo and Conditioner Bottles

Designers: Sharon Werner and Sara Forss

There are designers out there who approach and present design as if it's “magic” and there is only one rabbit in the hat. For us, the magic is in the design process—albeit not necessarily a linear one. Solutions need to be challenged at multiple steps to make sure they can hold up and stand the test. We can do that ourselves, but a client should also get involved. Clients need to take ownership of the brand—particularly small brands. They need to believe in it and live it for the result to be authentic and successful. They're often putting their homes or savings on the line. If they've been part of the process, they're more likely to be able to embrace the solution and find success. But collaboration doesn't always work smoothly. We have had to remind clients why they hired us.

You've kept your studio small for two decades! You don't waste time in staff meetings. But how do you avoid the stigma of being a “mom-and-pop” operation?

I'm not certain that we always avoid that stigma. But who cares? We have successful work to show and maintain a professional method of working. It's our feeling that if a client feels they need a larger agency with more manpower, then they probably do need that, and we're not a good choice for them.

Clients have gotten considerably more savvy in the past few years and realized that even in a larger studio, their project is generally handled by two or three people at most, although the meetings may be propped up with three or four extra people for show!

You create, manage, and package your clients' brand image, but how about your own brand? What do you do to keep it vibrant?

Meyer's Clean Day, Cleaners and Soaps

Designers: Sharon Werner and Sara Forss

We have a difficult time with this. It's definitely a case of the shoemaker's kids having no shoes scenario. We're attempting to launch a new website with a ton of new work, but it always takes a backseat to client work. However, I do believe that a successful project is as good for WDW as it is for our client, so that helps a little. But if anyone has the answer to this question, without working 120 hours a week, I'd love to hear it.

Compared with digital communication, print is now a luxury that fewer clients can afford. In which situations do you think print makes most sense?

Well, obviously packaging! Yeah! I love packaging. A few years ago, everyone touted the fact that websites created THE experience, which they can, but print has the potential to be as much or even more experiential. Think about cracking open a new book, the sound of the spine creaking, the smell of the fresh ink on paper wafting up, the smooth texture of the laminated jacket in contrast to the toothy, text pages. That's an experience that can't be replicated with an iPad.

As designers of print, we need to create those touch points within other areas of print. We need to use print to make an impression that involves all the senses. We need to create experiences, whether it's opening an envelope or a Hermes box.

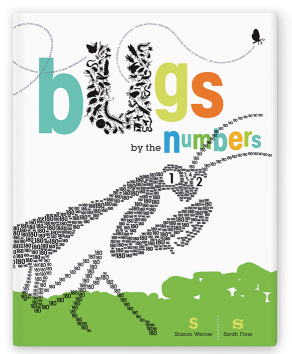

Octopus, from Alphabeasties and Other Amazing Types

AlphaSaurs and Other Prehistoric Types

Bugs by the Numbers

Published by Blue Apple Books

Authors and Designers: Sharon Werner and Sara Forss