Chapter 14

Interactive Multimedia Installations and Interfaces

How do you make sure that viewers and users, who are exposed to at least 3000 unsolicited messages a day, are actually remembering what they survey, read, hear, see, or touch? Interactive communication designers have an answer: They create immersive, open-ended narratives that turn passive spectators into active participants. On giant screens, on kiosks and on all sorts of stationary or mobile devices, the latest technological innovations are probed and tested to elicit the most dynamic response from the audience.

Exhibit designers, like interface designers, create information pathways with multiple options. The goal is to propose open navigation scripts for visitors and viewers to explore a given topic as they please. To create these learning experiences, you don't have to be an information technology (IT) expert. More critical will be your curatorial role—your ability to select artifacts, orchestrate programs, and develop sequential visual narrations. That's why visual designers hired in this specialty must have a general level of education allowing them to handle a broad range of topics—including medical, retail, automotive, finance, history, music, or mass media.

Today, no cultural exhibit, art installation, fashion show, promotional event, or industrial trade show is complete without some sort of interactive display integrating two or more media. To manage this type of project, visual designers work in teams, with people who are specialists and have the technical savoir faire, the UID experience, the engineering skills, or the scientific expertise necessary to complete the task. You don't spend much time sitting by yourself at your desk. Cross-disciplinary interaction between highly competent professionals makes this multimedia career path particularly rewarding.

Jeroen Barendse

Subverting the Mental Map

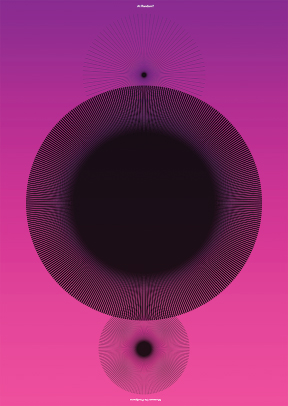

At Random? Interactive Media Installation

Museum De Paviljoens, Almere Designer: LUST

2008

From your vantage point, what is the greatest change you have observed in the last 20 years?

The current mantra that everybody is a designer or, more recently, that everybody is a curator, is true to the extent that there are now tools available by which almost everybody can design reasonably good-looking works. But those designs are most of the time re-creations of things somebody once saw. There is no innovation, no conceptual value in them.

The greatest change today is the way designers must reinvent their role if they want to be truly creative: On the one hand, they must develop a more research-based approach, and on the other hand, they must become creators of the very design rules and processes that will allow them to come up with innovative solutions.

What is the philosophy of LUSTlab—the more experimental division of LUST?

When we start a project, we let the project guide us. We have no preconceived idea what the outcome will be. We just design the process and react to that. We believe in creating a lot of different sketches, visually and in code, in order to familiarize ourselves with the material we are working with.

This also means wandering around, similar to the idea of a Flâneur in a city. This wandering allows us to look at things in a different way, to apply different gazes to the same problem. At LUST & LUSTlab, we often talk about the “vocabulary” of a project. During the research phase, we don't shape or design. We just try to build the “vocabulary”—with each sketch, idea or experiment embodying a new ‘word’. The richer the words are, the more elegant the sentences we can speak.

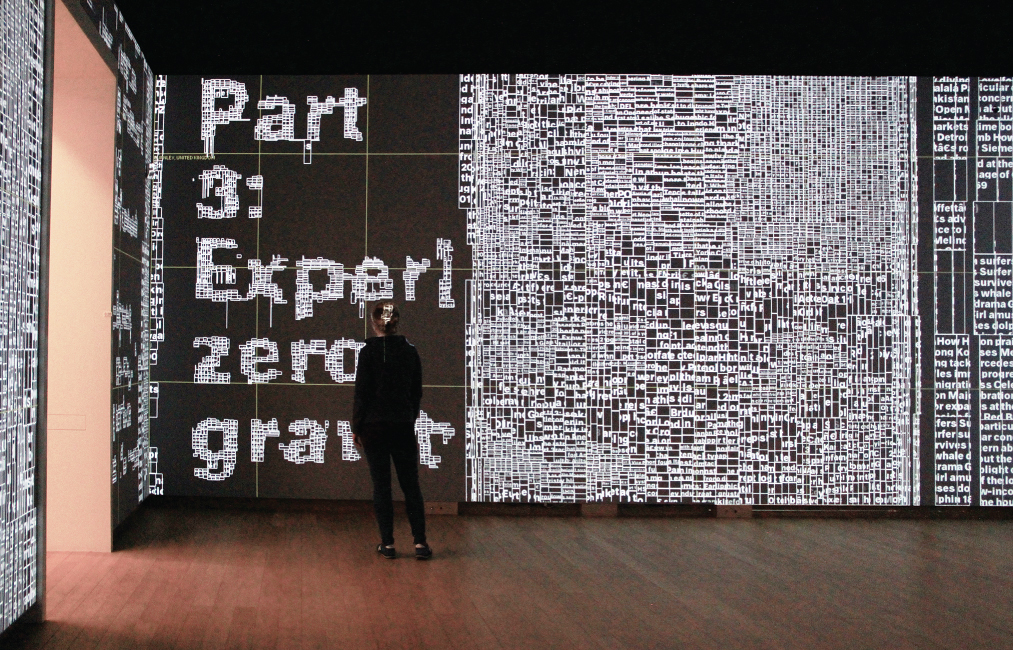

Type/Dynamics, Interactive Installation,

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Designer: LUST

2013

In an interview, you said that, for LUST, interaction design is the new literature. Would you say that interaction design promotes open-ended narratives?

We indeed see interaction design as the new literature. For us, it is not only about the interactive aspect of the effect; it is also about the narrative possibilities: narrative structures that go beyond linear or nonlinear. This new literature is also about literary aspects like references, analogies, structures, points of view, time—all contributing to the complete narrative. A visitor does not need to grasp all possible readings of a work at once; instead, multiple story lines unfold over multiple readings. All aspects from content to movement, interaction, data collection, and collaboration contribute to this new literature.

Does semantics play a role in your research process?

Yes, it does. We are very interested in literary anthropology. A lot of our projects deal with language, or the construction of a metalanguage, that can be expressed in type, but also in images.

Do you define interaction as providing open-ended narratives that can be interpreted and, if need be, finished by the user?

We believe that something that is open-ended is far more interesting in terms of experience than a clear end. When we just started LUST in 1996, we always used a text about the missing piece of the puzzle as a metaphor for what we wanted to achieve with our work. If you almost finish a puzzle and the last piece is missing, you will probably always remember that experience. Translated to interaction design, one can say that the viewer is needed in order to finish the puzzle.

Do you think that viewers of interactive media tacitly understand that they are part of the information flow?

If you mean that people are more and more aware of different media, I would say “yes.” My current students, for instance, can read and write in all kinds of media; they understand the medium they work in almost naturally. Even a few years ago, this was different. Current generations are born with the Internet around, allowing them a natural understanding of its implications and how we communicate with each other.

How do you define the role of graphic designers if the end product of their analytical process is a series of forms that design themselves?

Here, the design of the rules comes into play. Too often design is used to solve problems: real-world problems, but also editorial problems, organizational problems, and so on. We think it's better to approach something by not only looking at the problem but by looking at the opportunities as well. Only then can we define the task.

What quality or skill does a graphic designer need in order to be able to connect strings of codes with self-generative forms?

At Random? Interactive Media Installation

Museum De Paviljoens, Almere Designer: LUST

2008

Coding can totally absorb a designer, as the possibilities are endless as well as the variations that can be rendered. The solving of minor problems can easily become a day job. A good creative coder can take a helicopter view once in a while, reassess the work done, and focus on the conceptual ideas that need to be achieved. In that sense, we think the conceptual goal is still the most important, independent of the medium you are working in.

In the future, will graphic designers design rules rather than outcomes?

Yes, simply because the message that people need to communicate will be more and more media-independent. No longer printed, many graphic design works are formatted as PDFs and can be viewed on tiny mobile screens, on 30-inch monitors, or on multi-million-pixel screens. This calls for a different type of designer, who not only can design a PDF, a book, or a website, but who can also grasp the implications of the medium they are working with.

In our work, we explore the metaphorical difference between a symbol itself and the meanings a set of symbols may signify. Instead of being concerned with what these symbols should look like, we should probably be concerned with developing a new design morphology to fit the contemporary world we live in.

Julien Gachadoat

Demomaking for a Living

Interactive 3-D Vintage Postcard

Client: Office du Tourisme, Villeneuve-sur-Lot

Designer: Julien Gachadoat/2Roqs

2013

How did you discover your passion?

My dad brought home a computer in the 1980s. I was drawn to the machine instantly. You had to type in a series of instructions to launch a program of games. It was my first encounter with programming.

Later, in the '90s, as a teen, I was lucky enough to have an Atari ST—I was still fascinated by the interactive games. I joined a network of “pirates,” with different “crews”—kids competing to crack open the protective codes of the games, to duplicate them, and to share them around.

Cracking open a game was a matter of seconds for the most talented hackers. To broadcast their exploits, they would create a personalized home page with special “greetings” to introduce themselves and the game to friends and members of their posse. They would also taunt competitors—the “lamers.” Eventually, these “intros” became more sophisticated, with logos for each group, animations, scrolling texts, and even music.

These special effects, as displayed on “intro” screens, soon became more interesting, more intricate, and technically more advanced than the games themselves. I was mesmerized by the technology of this parallel universe. I knew enough programming to appreciate the sort of achievement they represented. And I loved their peculiar aesthetics.

I began to collect games—not for themselves but for their “intros.” I would try to reproduce the same visual effects I saw, even though my programming notions were rudimentary. I was self-taught. I was lucky to meet a friend at school, Michaël Zancan, with whom I was able to share my passion for graphic interfaces and algorithmic thinking. Eventually, Michaël and I went into business together.

Looking back, what were the major breakthroughs in your field?

From my point of view, the Internet changed everything. It allowed people to share ideas, to communicate, and to talk to each other in a democratic manner. For me, it was a breakthrough as well: I was able to access a lot of information, all of it crucial to acquiring an understanding of the new technologies as they evolved. That's how I discovered Processing, the open software, and the community around it. Soon I was able to create my company, 2Roqs, and focus on interaction design.

One of the first projects I created in 2005, in partnership with a London studio, came about as a result of connecting with someone on the Processing network. To this day, I keep up with all the various ways in which I can interact and connect with other communities, Kinect, for instance.

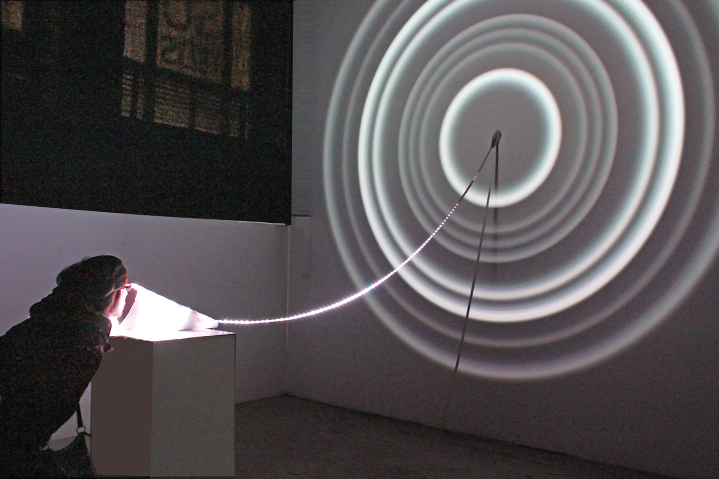

Murmur, Interactive Installation,

Client: Mirage Festival, Lyon

Designer: Julien Gachadoat/2Roqs

2014

Can you explain to our readers why open-source software, such as Processing, is a superior creative tool?

I am not sure that “superior” is the right word. “Different” is more accurate. Programming software like Processing offers users a way to code their own tools, whereas traditional software programs propose ready-made, preprogrammed computer tools. Open-source software promotes freedom but requires users to have methodology and be willing to engage in a more time-consuming learning process.

But in return, people who use open- source software such as Processing or Openframeworks have access to like-minded users who are ready to help them and encourage them on a variety of ways: project evaluation, suggestions for improvement, or sharing programs, for example. It's reciprocal: You also help others by constantly sharing your progress and discoveries with members of your community, adopting the “release early, release often” principle. This system is a lot more flexible than the closed system of regular software. The ground rule of open-source software is lateral sharing. All users are contributors, constantly sharing knowledge for the benefit of everyone else.

Along with your fascination for codes and programming, you are also interested in graffiti and typography. Can you give us examples of how you mix these disciplines?

The discovery of the graffiti universe was an experience on a par with the discovery of the “demos” world because it involved the same components: graphic design, typography, and underground cultural codes.

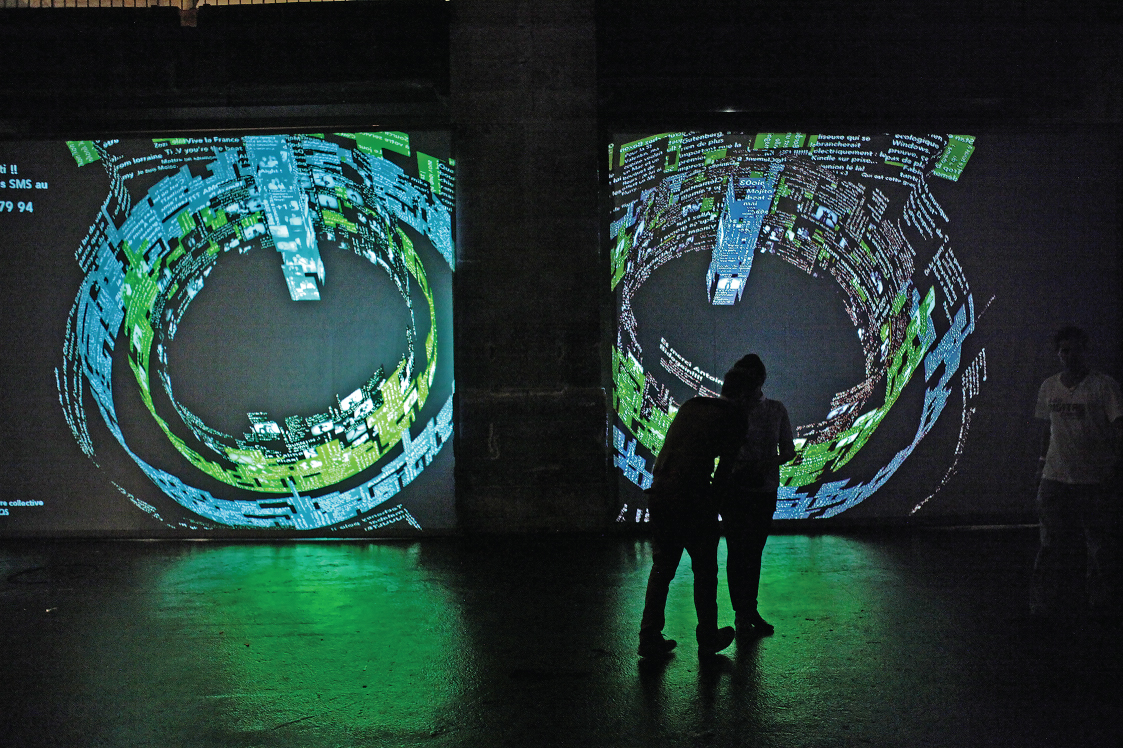

Our project, “Gravity,” is a good example of how we integrate everything we love. In this particular installation, on the façade of a building, we project texts that people send with their smart phone. That's our trademark at 2Roqs: We try to be surprising, amusing, and intriguing, while at the same time interact with spectators by getting them involved.

You have developed a number of “real-time” interactive installations. What next level of interactivity are you exploring?

I am right now developing a wearable tech project with NORMALS, an independent creative group devoted to the practice of speculative design. It's a virtual garment, conceived to be seen on a tablet. Its appearance morphs according to data relating to the persons who “wears” it.

Michaël is working on an application that allows viewers to actually enter into a photograph to see it from a number of different angles. It can be viewed as a projection, with the spectator moving about to look at the image from different perspectives, or it can be viewed on a tablet with a similar and startling result.

You have quite a few clients— mostly cultural institutions but also commercial ones such as wineries, electronics, or car manufacturers. What specific type of multimedia installations do you create for them?

We are offering our clients three types of interactive installations.

Full-size immersive installations in which spectators, by their movements and gestures, are able to transform the display. An example is the permanent installation at the Aquarium of La Rochelle, in which visitors can interact with schools of fish projected on the floor.

Interactive kiosks such as tables or vertical display units, popular with museums and cultural institutions, and particularly adapted to present educational content to a wide audience. Our clients include museums whose exhibits deal with science and technology.

Interactive applications for tablets that interpret, enhance, or visualize data.

Textopolis, Interactive Installation

Client: Semaine Digitale, Bordeaux

Designer: Julien Gachadoat/2Roqs

2012

You are French, but English seems to be the language most used by you and your colleagues to communicate in your field. Are codes also written in English? Is programming a truly idealist community?

The question of the “language” used for programming is complex. English is the universal language of programming, simply because it was originally developed in the United States in 1945. However, the language used to talk to a computer is not English—machines only understand a very short list of instructions, spelled out in a machine code, thanks to a compiler.

To program you must learn to write algorithms. In other words, you must learn to write a finite number of instructions to solve a problem in a reasonable amount of time on a given machine. Let me quote Bernard Chazelle, the famous Princeton University computer science professor: “Algorithms open new perspectives on science and technology. They are not simply useful tools— they truly herald a new way of thinking.”

Ada Whitney

The New Motion

Showtime Weeds

Client: Showtime Networks

Creative Director: Ada Whitney

Designer: Marlie Decopain, Marcelo Cardoso

Animator: Marcelo Cardoso

How did you become involved in making motion design?

My start in motion design was quite serendipitous. At the time, many of the early media companies were turning to artists, not designers, to work on the Quantel Paintbox, a precursor to Mac's. I started with painting SNL bumpers and fell in love with the collaborative and multimedia aspect of the work. The scene, a mix of writers, filmmakers, performers, musicians, editors, and artists, was intoxicating from a creative perspective.

You were a graphic designer, right?

I'm really a self-taught graphic designer. I relied on my background as an artist using my understanding of composition, color, line, and space to guide me. I found myself looking at letterforms as shapes when designing. I learned a lot on the job about typefaces, their form and character. I really loved that!

When you went from traditional design to motion, did you have to learn technologies that were cutting edge?

There is always a new technology to learn. To me that's one of the most exciting things about the medium. The cutting-edge tools at our disposal allow for new ways of thinking about the form our messaging takes and the way we communicate. For instance, with all the advances in interactive animation, you can create dynamic responsive animation that is user generated and designer guided. I think staying in touch with technology is vital to communicating with a plugged-in contemporary audience.

ABC Body of Proof

Client: ABC Networks

Creative Director: Ada Whitney

Designer: Marlie Decopain, Marcelo Cardoso

Animator: Florian Heger, James Bartley

What is necessary to know for broadcast quality that cannot be done today on the iPhone?

I'd say the most significant issues that arise with the iPhone are scale and readability concerns. Digital type and design choices that have expanded to include ultrathin, lightweight elements in broadcast HD are hard to read on the iPhone, as are very small images.

How is motion different from static design, other than the obvious?

Images are fleeting and change over time, so your message is not delivered instantaneously like a static image. It evolves and unfolds. The event becomes a timed experience allowing for emotional and cerebral arcs, not unlike theater or film. There is the opportunity to take the viewers and move them through space, over time and affect their perception through sound design, so that it becomes an immersive sensory experience.

Telling a story is key in your work. How do you structure stories?

I always think about the emotional arc and sensory journey we want to take the viewer on, and then, what information or content needs to be communicated. Creating an opening scene that sets the tone and teases the narrative is imperative; it's what will hook the viewer. From there we build content that unfolds and leads us to the peak of the message.

SNL Weekend Update Open

Client: NBC

Creative Director: Ada Whitney

Designer: Marcelo Cardoso

Animator: Marcelo Cardoso

Is motion the next big frontier for designers, or has it come and gone?

I think motion is already a big part of many designer's vocabulary. Not unlike still photographers, who migrated into the live action arena, I think many young graphic designers have embraced and added motion skills to their design acumen. With the explosion of tablets and smart phones, our culture's thirst for multimedia experiences has seemingly become insatiable. I think motion design is here to stay.

When you hire someone for the creative side, what do you look for?

The first thing I look for is a person whose has a smart and unique perspective. I respond to a reel that doesn't look like the past 10 I've seen. I like to see work that is well thought out and speaks the language of its intended audience. I shy away from reels that rely heavily on current design trends and the latest visual effects plug-ins. I look for someone with a keen sense of communication, design, color, motion, [and] sound and who understands the meaning of less is more!

Jean-Louis Fréchin

Asking the Right Questions

3-D Printing App, Sculpteo Vases

Designers: Jean-Louis Fréchin and Uros Petrevski

2012

How do you explain to your clients what you do?

For our clients—from global telecommunication companies to modest start-ups—we are forever attempting to enlarge the “scope of what is possible” and ”desirable” without losing the basic values of design: meaning, simplicity, emotion, and above all human endeavor. For my partner, Uros Petrevski, as for myself, design is a state, a prism for understanding, and a tool for questioning the world. We thrive on new challenges and new territories.

Your agency is called NoDesign because you categorically reject conventional ideas about design?

In fact, the “No” in “NoDesign” is an abbreviation of “nouveau.” In other words, new design—the new objectives of design. The name of my agency is meant to be a teaser, a way to start the conversation. People always comment on its name. It gives me a chance to explain to them that good design is something you don't see, particularly when it comes to designing an interface, where the “feel” is as important as the “look.”

For you, graphic design should be at the service of data visualization. Would you say that your passion in life is to create objects that allow users to better understand data and interact with it?

Indeed, I think of graphic design as first and foremost a formidable visualization tool. But, as a language, graphic design is not only objective; it is also subjective. It has a dual function. It can make you think and feel.

Twenty years ago, you were pioneering CD-ROMs. In your opinion, which digital innovation is most promising today?

As a communication tool, the Internet Protocol (IP) opens an infinite number of possibilities today. It's truly revolutionary. Nothing will ever be the same.

What sort of user experience do you try to create?

Today, we are developing an electronic format that will make it possible to create prototypes of objects, using the language of the Internet. These objects are in fact 3-D interfaces, like, for example, Sculpteo, an iPad or iPhone application that lets you create a ceramic vase shaped after a photographic profile of your choice. Or FabWall, a line of decorative wallpaper whose motifs are encoded in such a way as to give you access to personal information, family pictures, or favorite websites. We want to merge the functionality of traditional interfaces with that of interactive objects. We want to come up with meta design projects.

Should graphic designers be programmers as well, in order to be able to conceive truly innovative products, services, and experiences?

To be creative today, you have to use the most contemporary tools. In my opinion, being able to write programs is critical. Graphic designers who have an even rudimentary knowledge of coding will discover new territories of expression—from 2-D screens to 3-D interactive objects.

Some of your inventions are utopian—like the “dépendomètre,” an instrument that is supposed to measure your level of dependency on social networking. Are you inspired by science fiction?

What we call utopia is usually an invention that has yet to be shared with others. The idea for the dépendomètre came about when we realized that, for many people, dependency on social networks was a very real problem. Free services, free software, free applications, and free downloads are deceptive. They are not free. As the saying goes, “If you're not paying for it, you are not the customer, you're the product.” Our intention was to invent a device that allowed Internet users to measure and visualize what is fast becoming a dangerous form of addiction. This device is a smart tracker, not unlike the body analyzer, Withings, a scale that monitors your weight and heart rate and sets health goals for you.

“Cloud” Dependency, Monitoring System

Designers: Jean-Louis Fréchin and Uros Petrevski

Prototype 2013

You are also an expert in digital design strategy. How would you describe this new discipline?

In the digital age, figuring out what to design is critical. Before you look for answers, you have to make sure that you are asking the right questions. Relevant design solutions will propose new and different products. They will come about as a result of innovative thinking emanating from technologically savvy organizations with an unconventional approach. For me, digital design strategy is a process that yields a range of unexpected “possibles,” usually based on the interaction of trans-disciplinary practices.

Interactive Tags for FabWall

Designers: Jean-Louis Fréchin and Uros Petrevski

2010