Chapter 19

Making Choices

Education choices are never easy. Financial concerns weigh heavily. But there are some alternatives. Here is a guide: You should find a two- or, better yet, four-year undergraduate program at an art college or general university that offers a bachelor of fine arts (BFA) or equivalent degree. This is not to imply that a liberal arts education is to be ignored; liberal arts is a prerequisite that must be pursued in tandem with design classes. However, two years is barely enough time to learn the tools, theory, history, and practice of graphic and digital design, as well as to develop a marketable portfolio. Of course, as four or more years in art or design school may be impossible for some and excessive for others, continuing education is also an option.

For those with the desire and wherewithal, a graduate school education can be beneficial. A few people possess a natural gift for design and, with only a modicum of training, might turn into significant designers. But they are exceptions to the rule. Untutored designers usually produce untutored design. Although good formal education does not make anyone more talented, it does provide a strong foundation upon which to grow into a professional. While taking the occasional design class is better than no schooling at all, matriculation in a dedicated course of study, where you are bombarded with design problems and forced to devise solutions, yields much better results.

An estimated 2300 schools (two and four years) offer dedicated and ancillary graphic design programs and graduate about 50,000 students each year. Each year, more schools are adopting some kind of graphic or digital design program that ranges from basic instruction of computer programs (InDesign, Photoshop) to advanced typography to a range of complex digital media.

The investment is considerable, so look at many schools before selecting a two-year, four-year, or continuing education design program. Then create a portfolio that will make you an appealing student.

Undergraduate

Whether you decide on a dedicated art school or a state or private university art department does not matter (financial and location concerns often dictate this decision). More important is knowing the strengths and weaknesses of the chosen program. The fundamental instruction in the second year sets the tone for those to follow. Here are the areas to examine.

Computer. While some design courses offer instruction in computer programs after more basic conceptual and formal issues are addressed, others dive right into the tool as vital to design practice. It does not really matter at what point digital media application is taught (although most agree that it is better to understand the theory of design before attempting its practice), but computer skills must be keenly supported through individual and laboratory instruction throughout the program. Understanding what design is and how it works in both a philosophical and practical context may be more important than doing the work, at least at the outset. If a student does not know what design is and at whom it is aimed, then making marks on paper or screen is fruitless.

Graphic design is not a self-motivated fine art, and although the lessons of art may be integrated, communications theory in its various forms (semiotics, semantics, deconstruction, and so on) are the essential components of a well-rounded design education. The computer and everything it touches is not an end but the means. Yet it will become, if it has not already, the primary delivery mechanism for designed information and experience. If the program you are examining has too little or too much computer studies, find how design is introduced and taught.

Concept. Design is not decoration but, rather, the intelligent solution of conceptual problems; it is the manipulation of type, image, and, most of all, the presentation of ideas that convey a message. A strong design program emphasizes conception—developing big ideas—as a key component of the curriculum. Concept courses should include two- and three-dimensional design in all media. In short, a “trade school” education will not be as fulfilling as a design thinking course of study.

Type. This is one of the primary means by which civilization communicates. A type font is not just something that comes installed in your laptop. Classes in type and typography should, therefore, begin at least with the history of movable letterforms from the fifteenth century to the present—the art and craft behind them and the reasons that type, conventions exist. The application of type, past and present, in various media, and the purposes for which types and type families have been used should be covered. Type instruction should include a range of endeavors, from metal type founding to digital fontography. Once type has been fully addressed, typography—the design of typefaces on the page or screen context—should be thoroughly examined as both a reading and a display vehicle. Any study of typography should include intense debate about its function—legibility versus illegibility.

Image. Design is about image making (and storytelling), and a well-rounded program includes classes devoted to photography, typo-foto (the marriage of type and picture), and illustration. Certain courses emphasize computer programs such as Photoshop, and these are indeed necessary. But a good program makes the distinction between computer- generated art as style and imagery as essential to narrative.

Advertising. Some design departments segregate advertising from graphic design; others integrate the two. It is, however, useful for the graphic designer to learn the techniques that go into this very public medium. What's more, advertising agencies are employing large numbers of digital designers to execute new ways to reach the public. Learning advertising's requisites will stand you in good stead.

History. Most design departments are not equipped to offer more than survey courses on certain aspects of design history. Nevertheless, this is an integral part of design education that should continue throughout a design program (and not as an elective, either). It is essential to know that graphic design has a history, and to be familiar with the building blocks of the continuum.

Digital Media. The volume of cross-disciplinary endeavors that affects designers today is only going to grow rapidly in the future. Training a student to design in the print or Web environment is necessary, but knowledge of other media—film, television, video for tablets, and handheld devices—is not only imperative but also will open the student's eyes to the unlimited possibilities that design now offers.

Production. How can you design without knowing the means of production? For a designer, being detached from the output, whatever it is, is like being a doctor who never interned on a human being. Check on labs and workshops that provide production instruction.

Business. At the undergraduate level, few schools focus on the business of design in terms of starting a studio or firm, and all that it entails. Most design schools are concerned with developing the skills that lead to marketable portfolios, and energies are aimed at helping students get internships or jobs. Prudently, they do not encourage neophytes to start businesses immediately out of school. Nonetheless, business is an important aspect of a sustainable career, so even if developing business plans and spreadsheets is inappropriate at this level, courses that address general business concerns are useful.

Portfolio. The most important concrete result of a well-rounded education is the portfolio. Classes in how to develop portfolios usually begin in the senior year, when the student is given real-world problems in various media with the goal of creating a strong representation of talent and skill. A diploma is important, but the portfolio is evidence that a student earned it.

Placement. Schools with reputable internship programs are invaluable. Many programs have established relationships with studios, firms, and corporations throughout the United States and, often, the world. These schools place students and graduates in many working situations and monitor their development. Experience from these internships or temporary jobs (which may start in the sophomore year) is priceless, and, on occasion, they lead to full-time positions. Good placement offices also keep job-bank notices and help the students prepare for these opportunities.

Faculty. Let's not forget the teachers. A strong faculty is what makes all these programs work. Some schools maintain full-time faculty; others use adjuncts who are professionals (part-time teachers who work full-time as designers, art directors, creative directors, etc.). Both situations are equally good. The value ultimately comes down to the individual. Inspiring teachers make the difference. Find out who they are by reading their bios online. Google has become the primary reference source.

Graduate School

Today, a growing number of two-year graduate programs address general or segmented design profession concerns. Graduate education is not for everybody, but it has become a viable means of developing areas of expertise that were ignored or deficient in most undergraduate schools. The master of fine arts (MFA), master of arts (MA), master of professional studies (MPS), and associate degree, which are the typical degrees from graduate programs, are not necessary to obtain jobs or commissions (although, if you want to teach at a university, the MFA and PhD degrees are usually mandatory), but they do indicate accomplishment: The designer has completed a rigorous course of study. For those interested in intensive instruction and networking, the graduate school experience can be highly beneficial in creative and practical ways.

Graduate school is, however, a major investment in time and money. The average tuition is between $19,000 and $35,000. Some schools insist that students devote the majority of their time to school-related work; others schedule their programs so that students can work at regular jobs or on commissions while attending evening classes. And new distance-learning programs are flexible enough for students to work at home at a reasonable pace.

Eligibility for graduate programs varies. All candidates must have bachelor or other degrees from undergraduate institutions (these need not always be design degrees). A few exceptions are made for work/time equivalency. Some programs accept all students immediately after graduating from a four-year undergraduate art or design school; others seek students who have been working professionally for a year or more prior to returning to school. Portfolios and interviews are usually required, and the portfolios must include school or professional work that shows distinct talent and aptitude. Some entry requirements are more lax than others, but if the portfolio is deficient—if the prospective student shows nothing, for example, but mediocre desktop publishing work—additional training and practice are recommended before reapplying. Graduate programs are open to applicants of all ages who meet the entry requirements.

Graduate school is a viable means for those who want to switch careers or to achieve greater proficiency and better credentials.

If a prospective student meets all the eligibility requirements, the next step is to explore programmatic options to determine which schools are best geared to the specific educational need. Possibilities are numerous. Some programs are fairly free-form, where teachers guide a student along a self-motivated course of study. Others are more rigidly structured, with a set of specific goals to attain by the end of each study period (which may be a semester or more). Some programs are geared toward specialties; others are more general in scope. Among the specialties are corporate design, advertising design, interaction design, product design, and branding, among others. A number of programs have philosophical and even stylistic preferences, while others avoid overarching ideology of any kind. Some are concerned with social activism, while others are devoted to the commercial marketplace and entrepreneurship.

Some programs are better endowed than others. Most programs have a cap on how many students are accepted annually. It is recommended that prospective students request literature from programs and personally visit those that are of most interest (some have open information sessions, whereas others grant individual tours).

Applicants commonly apply to more than one program, although each may require different materials.

The following are programmatic concerns that should be explored before applying.

Scope. A graduate program involves advanced study and is not simply an extension of undergraduate school. While a curriculum may include components that overlap an undergraduate or continuing education course, it must go way beyond what is provided at these lower levels. When looking at a prospectus or talking with a graduate school admissions officer, determine the scope and goals of the program and the expectations it has of its students.

Philosophy. This is related to scope but demands its own category. A graduate program may require that students adhere to a particular pedagogical concept. This can be anything from minimalist (modern) to complex (deconstruction) design, classical, avant garde, or any other approach. It can be based on a certain iconoclasm or eclecticism. Whatever the philosophy may be, decide by talking to former students and teachers about its compatibility with your own attitudes.

Tradition. While undergraduates are wrapped up in technology and processes that will allow them to get jobs immediately upon graduation, graduate programs should allow for greater reflection. A well-balanced program encourages students to work with their hands as well as with machines. Learn whether workshop or lab facilities are provided for this.

Technology. A graduate program should be state of the art. The design world is becoming inextricably connected to latest making machines. Advanced knowledge of the tools of production and creation is requisite. Most contemporary graduate programs spend at least 50 percent, if not more, of class time on technological concerns and have the hardware and labs to support thorough study:interdisciplinary studies. Graphic design graduate programs cannot afford to be specialized to the point of isolation. The more that relationships with other media and genres—inside and outside the design bubble—are carried out the better, even if only in survey courses.

Facilities. Graduate schools should provide facilities that encourage students to work in a more focused environment, both separately and in tandem with others. Facilities may include small studios or networked workstations in an integrated studio setting. It is important to know how you work best and in what kind of context. Some programs encourage the open studio; others simulate a design firms' environment. The location of the campus is also important—for example, its proximity to otherinstitutions or businesses.

Faculty. A program is only as good as its teachers. Some graduate programs pride themselves on employing the leading practitioners in the field; others rely on full-time professors. Balancing the two is usually a good solution. In most course descriptions, the faculty members are listed along with their credentials. These should be seriously studied.

Exhibition. Most graduate programs are concerned that student work be tested and, ultimately, published, exhibited, and even presented on stage before an audience. Although what a student learns is most important, the quality of the results is evidence of a program's effectiveness.It is useful to examine both the means of presenting student work and the work itself. Publications are available to applicants, as are schedules of student exhibitions.

Responsibility. A graduate program may be considered a cloistered existence. Increasingly, however, this is an opportunity for students to do the kinds of socially responsible projects that may less frequently be options in the workaday world. It is important to explore how a program contributes to the broader community.

Business. Even in a cloister, the real world must have a place, and the graduate school is indeed a good place to examine the business world. Graduate students are more likely than undergraduates to open their own businesses once they have earned their degrees. Design management and property law are important areas of concern at this level. Business plans are a must-have skill.

Thesis. The primary degree requirement is the final thesis. It is important to understand what the program expects of its students and how it goes about developing student thesis projects. What is involved in this process? Are there thesis classes, faculty advisors, review committees? Must the thesis be published? Will the thesis cost the student extra funds? Ultimately, the thesis can be a portfolio or a key to a new career.

Distance Learning

The computer has changed everything in our lives, including the way we are taught. Home studies or “distance learning” is not a new idea. Correspondence schools taught students how to letter, draw, and otherwise do rudimentary and advanced graphic design. Today, with access to various computer-driven online classrooms, the ability to learn complex subjects in a virtual environment is easier every year.

For the harried neophyte looking to change careers or the professional wanting to expand, improve, and elevate their skills, distance learning offers a wealth of options from scores of good old and new institutions. Some are entirely online, while others require a short annual residency as part of the degree qualifications. These virtual campuses also cost less than brick- and-mortar colleges and universities.

Continuing Education

Graduate school is not always feasible for those who work at full-time jobs or who choose to obtain specific skills as a means to widen their career path. Therefore, the most common method of developing additional skills (and receiving inspiration) is through continuing education, once called night school. Some general colleges and universities offer programs, but usually it is the province of the art and design schools and colleges to offer a wide range of professional courses, from introductory to advanced. In addition to a potpourri of professional courses, some institutions offer intensive weeklong workshops with master teachers. Abroad programs also fit this category.

Some of these programs are designed exclusively for working professionals (and require a fairly accomplished portfolio as a condition of acceptance), while others are open to a broader public. Enrollees in continuing education classes run the gamut from professionals who seek to better themselves (maybe to earn promotions in their current workplaces) to neophytes who want additional career options. Classes are available for any level of expertise and are useful in acquiring knowledge, experience, and, in some cases, job opportunities.

Obviously, reputable continuing education programs are best, and they are usually offered by art and design schools. Most computer tutorials are useful, particularly as insight into common layout, illustration, photography, and graphics programs (many older professionals use these sessions to learn or brush up on new skills).

Andrea Marks

Old School, New School

Do Good Index

Designer: Christopher Shults

School: Oregon State University

Project: Undergraduate senior project: a mobile app that allows users to scan barcodes to see how sustainable a product is. After receiving the product score, users can choose to donate a total of the product cost toward a portfolio of charities that help offset some of the adverse effects of consumption.

2013

How important is it for designers to attend a design school versus a traditional university?

I teach at a state university with over 26,000 students, more than 200 undergraduate programs, and over 80 graduate programs. This diversity with so many programs and activities on campus is great for the students and allows for many interesting cross-disciplinary collaborations. We are located in a small college town (population 55,000), so though the town is limited in terms of design studios to intern with, there are many on-campus internship opportunities, and students have to dig a little deeper and make more of an effort to go to AIGA Portland events, which, in turn, makes them really special.

You've been teaching for over 20 years. What curricula are different now than when you began?

In 2000, the graphic design faculty completely redesigned the curriculum and brought in many new classes, including a class on design process, a class on collaboration, and a senior capstone project class. We are currently in the middle of another curriculum revision, only this time it is with our new School of Design. In the fall of 2012, the graphic design program at OSU migrated from the art department and merged with apparel, interior, and merchandise management to form a school of design. The larger change is that we are now located within the college of business. The new curricula we are developing has a design core with classes in collaboration across disciplines, consumer behavior, user-centered design, marketing, and entrepreneurship. Our new curricula have more classes in cross-disciplinary collaboration and systems thinking.

How have the students changed?

Fortunately, throughout the 20 years I have taught at OSU, students' enthusiasm and interest in learning has not diminished at all. We have a very competitive program (we admit only 25 students per year), and they become a very close community over the four years. They juggle much more than students did 15 or 20 years ago—keeping up with technology [and] part- and full-time jobs, and I am continually amazed at how much they can still give to graphic design.

How has your teaching evolved over the years?

When I began teaching, there were maybe one or two books on typography and no books on graphic design theory, history, or criticism. I love that there are more resources today, but it can be tricky to figure out how to teach a subject properly (history, context, etc.) in only 10 weeks. I have always looked at teaching like a design problem—I ask myself what is the narrative I want the students to come away with after 10 weeks (learning outcomes) and what types of projects will engage them and allow them to really engage in their learning? My role is to guide them through the subject matter and help them see the role of design in the broader context.

Brand People Story

Designer: Maschell Cha

School: Oregon State University

Project: Undergraduate senior project: A 36-page book about three individuals' relationships to brands.

2013

When you guide graduating undergrad students, do you recommend going directly to graduate school? Getting a job in a studio or firm? Taking internships? Or is there another alternative?

I typically do not recommend that path, as I feel students need to take a break and find out what they are really passionate about before heading back to school. Ten or 15 years ago, a graduate degree for a graphic designer was a more traditional MFA in graphic design. Today, there are many diverse grad programs, from MFAs in entrepreneurship and writing and criticism to MBAs in design management, strategy, and business, and online programs are also popping up. Waiting a bit allows students to see what they want to focus on next (and sometimes an employer will even pick up the tab for graduate school!).

What is most essential to learn in the twenty-first century?

It is essential for students to understand that design is a process and not only an end product. Design thinking and strategy are integral to the design process, and students need to be aware of audience and context for what they create.

What should students know when they leave school?

Students have to graduate with the idea that they will be lifelong learners. Our world is too complex and is changing too quickly to ever sit back and say, “Great, now I have graduated and can apply what I know.” Some of what a student learns in school will be applicable, but much will not one or two years out. What will be relevant is how a student learns to dive deeply and creatively into a project (the process, methods, etc.) and the ability to adapt to change.

You can see potential . . . What do you see?

I look for much more than raw talent when assessing a students' potential. I want to see how they think, organize, write, and talk about their ideas and work. I also want to see how curious they are about the world and how resourceful they are. I am aware that all students communicate and process information in different ways, and it is my job as an educator to find ways to evaluate and motivate students to their full potential.

Lita Talarico

Educating Design Entrepreneurs

North

Design Entrepreneur: Donica Ida

School: SVA MFA Design

Project: A vacation-based mobile application that locates meaningful places in nature through crowd sourcing.

2014

What do students require today as education fundamentals?

It is no longer acceptable to simply be a service provider, so we must educate students to not only create their own content but also to work collaboratively. This includes fluency in various visual languages and communication platforms.

Are MFA degrees truly necessary in achieving the fundamentals?

Not necessarily the fundamental skills, but definitely for more intensive research and exploration.

What else does an MFA degree provide for a designer?

In the past, one needed an MFA in order to teach, and that's what compelled most students to pursue one. This is no longer the case. An MFA now allows a student two years of focused study, not only on research and history but also on practice and viability.

What is the most unique quality of the MFA Design/Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program?

The MFA Design program is about getting students to create a project from idea to market and helping them with all the steps that are required in between. Students start off with their own concept, using various media to create and develop a thesis, or “venture,” as we call it, for a marketplace of goods and ideas. They work individually and collaboratively for two intensive years, to develop objects of value that are aesthetically sound and conceptually viable, guided by a network of renowned faculty—all practitioners.

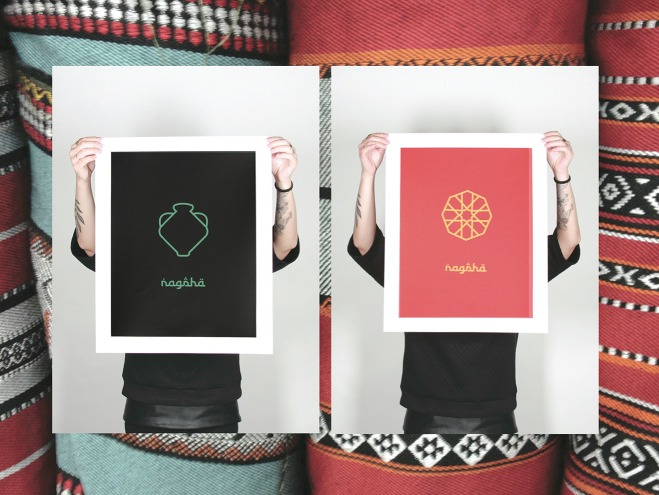

Nagsha

Design Entrepreneur: Danah Abdal

School: SVA MFA Design

Project: Online cultural communication between countries in the Mideast.

2014

Is there a possibility that entrepreneurship will become just another buzzword or fashionable trend?

Yes, the word perhaps but not the concept. This is not a new idea. In the nineteenth century, William Morris and designers who were part of the Arts and Crafts movement designed, made, and sold objects. The faculty and students at the Bauhaus created and manufactured products for the marketplace.

How do you teach students to stay current?

We don't have to teach them—they are current. They teach us. All we have to do is provide the education and tools so that they can realize their goals.

!Lei Lei!

Design Entrepreneur: Franacisco Hernandez

School: SVA MFA Design

Project: An educational system for Mexican-American children and their parents.

What does “maker” mean and imply?

It means thinking and creating and producing and delivering by filling a perceived need in society and hopefully making a difference and ultimately changing the world.

What do you look for in new students?

Someone who wants to commit themselves to two rigorous years of tapping into their creativity and dedicating themselves to finding a way to direct it into useful, meaningful, and sustainable products, whether social or commercial.

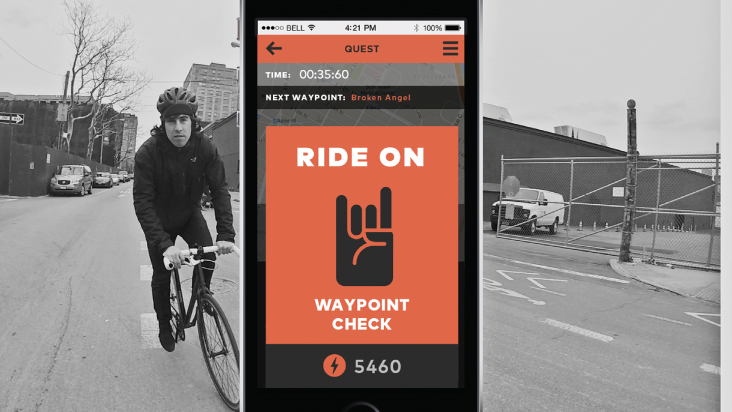

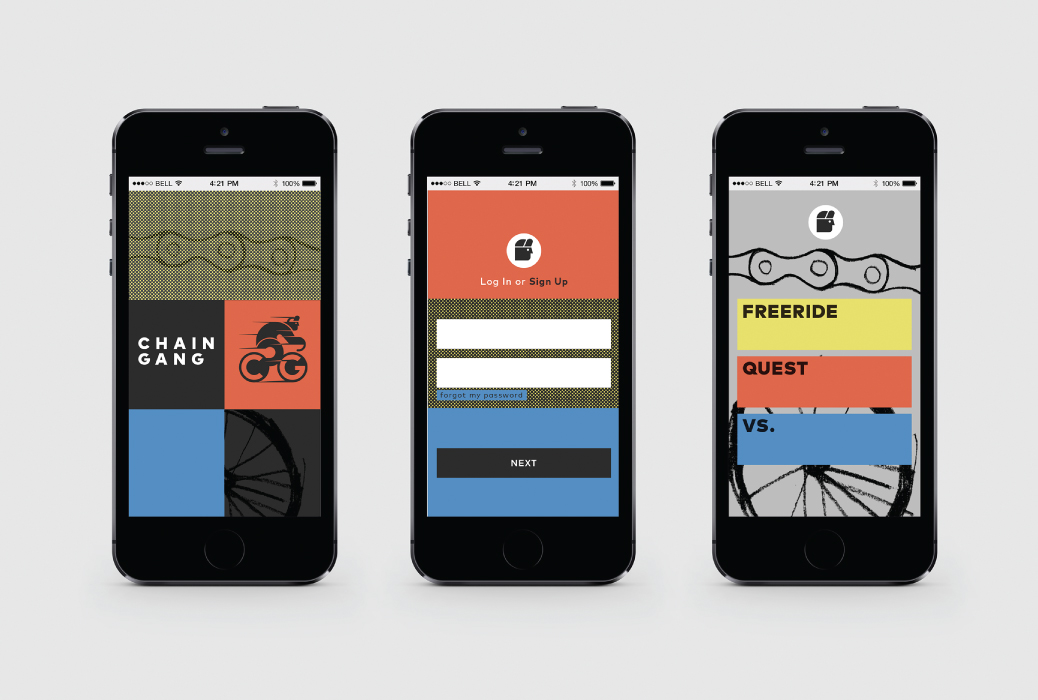

Chain Gang

Design Entrepreneur: Tomás de Cárcer

School: SVA MFA Design

Project: An adventure-based mobile app that rewards cyclists for exploring New York City.

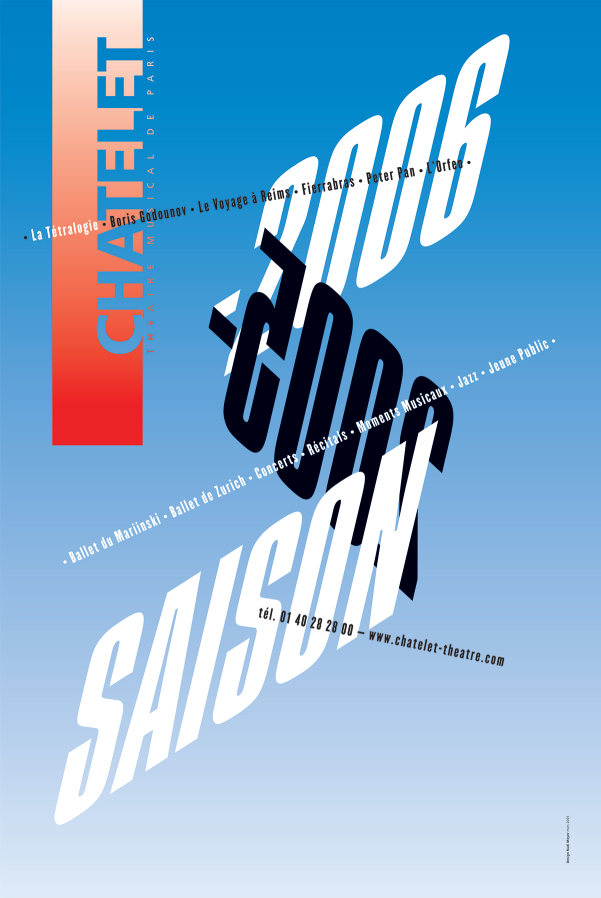

Rudi Meyer

Developing the Right Attitude

Poster, Theatre du Châtelet

(2004–2005)

Designer: Rudi Meyer

Just a quick question before we start: Was typography the cornerstone of your practice?

Typography was certainly important. I was for some time director of research at the Atelier national de création typographique. But I was equally intrigued by everything having to do with spatial representations—maps, in particular. I taught in a school specializing in the “sciences géographiques.” I got involved with Roger Tallon and Massimo Vignelli when I redesigned trains and rapid transit system maps for the national French railroad company. I also got assignments designing exhibits and signage systems for museums. It was all related to typography, somehow.

You also did a lot of print work?

Yes—logos and corporate identity programs, books, catalogs, posters, and so on. I even designed watches.

In your opinion, are the teachings of Armin Hofmann, whose principles were adapted to the technology and design sensibility of the 1960s, still relevant today?

I find his principles more helpful than ever. He was not trying to be an expert; on the contrary. He believed that, in the long run, developing the right attitude would be more useful to his students than acquiring all the latest professional skills. He taught me to be steady in the pursuit of my goals—while, at the same time, keeping an eye on future developments and directions. He insisted we do not confuse communication with information . . . self-interest with general interest . . . knowledge with understanding . . . expansion with growth . . . or fundamental research with applied research. He also wanted us to differentiate between two approaches: appealing to the mind versus appealing to the emotions.

That's what you've learned from Armin Hofmann. What is the most important thing your students have learned from you?

You'd have to ask them! What I tried to instill in them is a sense of curiosity toward other disciplines and practices. I wanted to give them a design methodology they could adapt to other domains. Like Hofmann, I didn't present graphic design as an expertise but as a state of mind. Technologies and tools keep changing—and they do so at a faster and faster pace—but the creative process remains the same.

Poster, Theatre du Châtelet

2005–2006

Designer: Rudi Meyer

Still, graphic designers today have new opportunities—they have been liberated from the traditional constraints of print technology—but they must overcome new hurdles nonetheless. Would you agree that, paradoxically, it's both easier AND harder to be creative today?

Yes, I do. Back then, various constraints used to curb your creativity. But in the process of overcoming difficulties, you would be forced to explore an ever-expanding range of possible solutions. Each new invention was the result of having pushed the limits of technological restrictions. For example, traditional typography made it practically impossible for us to create curved headlines—yet we found a way to do it!

To go from the sketch phase to a full mock-up of a project took a lot of savoir faire, but it also required that designers and their clients use their imagination to visualize the final result. You also had to learn to translate forms from one medium to the next. Case in point, the original gouaches Cassandre did as mock-ups for the lithographers. Just compare them with the final printed posters. What a difference under close examination! What you'd assume was Cassandre's unique rendering style is, in fact, the result of the work of some anonymous lithographer. Yet, if you compare the gouaches with the posters from a distance, they look absolutely identical. Cassandre knew how to ask for what he wanted.

Today, the situation is exactly the opposite. The images on our screens and the laser printed mock-ups are often more beautiful than the offset end products. In our day and age, the dematerialized digital language leaves no trace on the images it helps generate, as did pencils, paintbrushes, or calligraphic ink pens. The tools are no longer here to guide our hand. Not only do we need to be extremely vigilant when we design, but we also need to be on our guard when we try to come up with creative solutions.

Annual Report, Interior Spread

EDF Electricité de France

Designer: Rudi Meyer

1990

Swiss graphic design, often identified as “International Style,” has made a comeback under the name of “Flat Design.” Is it a good sign, in your opinion?

Virtual “realism” had a raison d'être at the beginning of the digital age to help users connect with various functionalities. These “skeuomorphic” representations brought an emotional dimension—thus, the silly fake leather, the phony wood surfaces, and the hyperrealistic “push” buttons—not to mention the profusion of drop shadows so popular with the previous generation of designers.

At this point, Flat Design is first and foremost a reaction, but it is also a reinvention of abstraction—a good thing in my opinion. Information is taking precedence over baroque expressionism. Today, the International Style has acquired a nostalgic appeal, when, in fact, its codes are recapturing the spirit of Aesthetic Functionalism—of Form Follows Function. Will it last? Time will tell. In all likelihood, another style will soon replace Flat Design. You cannot stop designers in their constant search for the next thing.

Can you give us three typographic principles that could help young graphic designers today?

1. Think of a page or a screen as a space where forms and emptiness interact with each other.

2. Do not confuse hierarchy with differentiation.

3. Try to create startling results with as few elements as possible.

Lucille Tenazas

Idiosyncratic Contexts

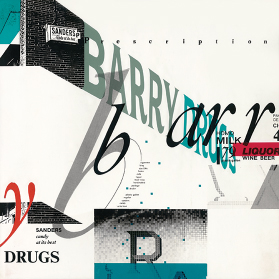

Barry Drugs: Street Signs Project

Client: Cranbrook Studio assignment

Designer: Lucille Tenazas

1981

You are the recipient of a 2013 AIGA Medal for your “role in translating postmodern ideas into critical design practice.” It would be very helpful to our readers if you could explain the difference between a critical and a noncritical design practice.

I had to figure out for myself why I got the medal in the first place. I was unsure about my “role in translating postmodern ideas,” as the AIGA put it. I felt that my greatest contribution was the way I had been able to be both a critic and a designer. I am most comfortable with the idea of a “critical design practice.” By this I mean that I am critical of my own design process.

As a young designer, I worked much more intuitively. My design solutions were spontaneous reactions. I happened to be gifted; I have a native talent; I have a good typographical sense. It was too easy, perhaps. Once, someone asked me, “Lucille, why did you do this?” and I couldn't answer. I had to learn to give meaning to my design.

But let's go back to the “postmodern” part of the AIGA statement about me. Postmodernism got such a bad rap. Truth be told, I was much more of a modernist at heart than a postmodernist—I went to Cranbrook in the mid-1980s, when postmodernism was exploding and the conservative, corporate design center of New York was being replaced by California. Originally, postmodernism had more to do with literary criticism than with design. Only later did it become associated with architecture and the other arts. Anyway, I was a postmodernist only in the sense that traditional design history wasn't part of my vocabulary. Being born and raised in the Philippines, I had no idea how to put postmodernism into a coherent historical perspective.

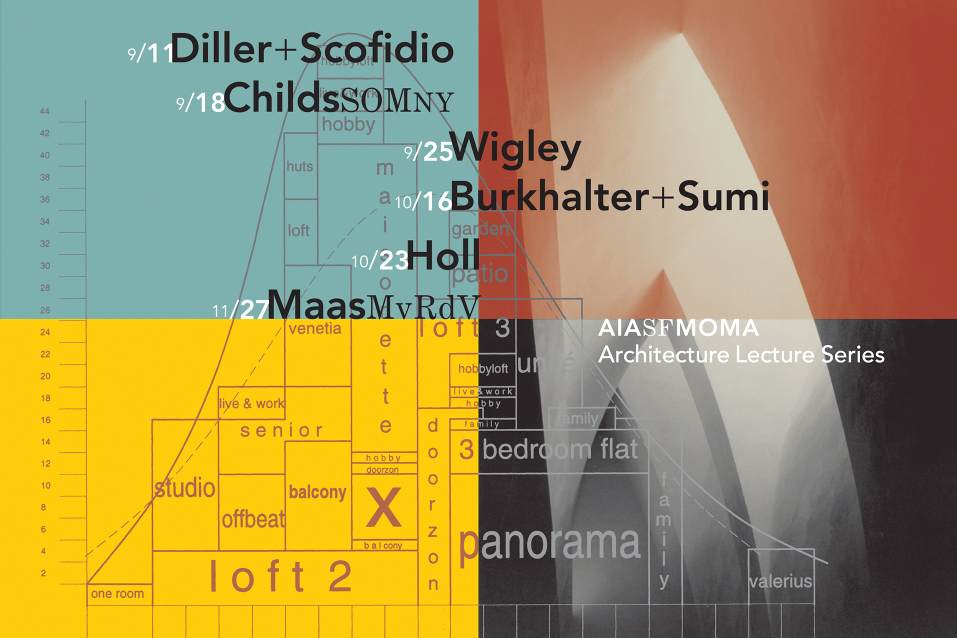

SFMOMA Lecture Announcements in Collaboration with the American Institute of Architects (AIA San Francisco Chapter)

Client: SFMOMA

Designer: Lucille Tenazas

2000

In an interview, you said that for you, “form is easy.” You are burdened with so much talent! How did you overcome this “handicap”?

Eventually, I came to question the way I intuitively used typography. Other designers, whose work I admired, were able to display levels of meaning in a singular image, whereas I layered letterforms, using words as texture or as background noise! I was cutting and collaging, which was the trend at the time. I created hybrid images and manipulated photography in a very uncritical way. I even thought that photography was at the service of design!

The result was pleasing, but was it provocative?

What is wrong with my methodology, I wondered.I became interested in the linguistic dimension of graphic design. I had been taught English in a very formal way in school in the Philippines, and it remained forever associated in my mind with academic exactness. This rigorous approach helped me reassess the relationship between content and meaning. I discovered semantics. I started to see words as “signs,” as objects you can touch. The fact that I was teaching typography was an additional incentive to formalize my new interest in language.

Being Filipino, did you feel at a disadvantage, or was your multicultural education and your non-American design sensibility an asset?

I remember at Cranbrook, I felt clueless compared to my fellow students. For example, I used lots of colors in my work, whereas everyone else was doing tasteful black-and-white compositions, with just a red dot or a red line as an accent. I was asked: “Haven't you heard of Swiss design?” Well, not really. But I quickly absorbed what it was all about. Same with Russian Constructivism, Dada, or Fluxus. I had to educate myself in the art and design influences that practitioners were referencing.

I didn't know who April Greiman was! I had a different trajectory. I was older than my classmates. Coming from a developing country and feeling less experienced in design issues, I felt unsophisticated—yet, strangely enough, my work was better than the work of other students who tended to mimic design pioneers from the past. However, not belonging—not being able to explain why I did what I did—forced me to develop my critical thinking. I came to accept that my work would not look the way it did if I had been raised in the USA and if I had had a more comfortable relationship with the English language.

I wanted to learn to design like an American. It never really happened—because I was different, I ended up influencing my American classmates. I am very proud of that: I could never conform, yet I am part of the American design history saga.

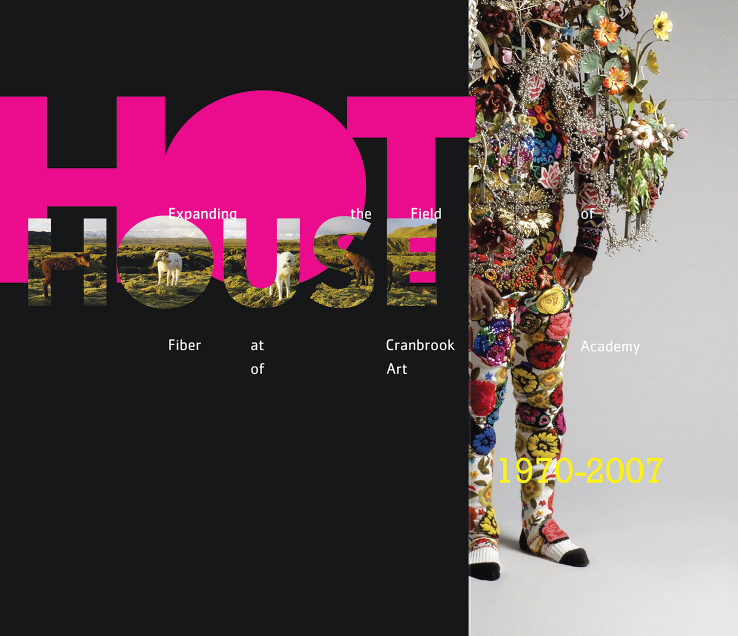

Hot House: Expanding the Field of Fiber at Cranbrook Academy of Art

Client: Cranbrook Academy of Art

Designer: Lucille Tenazas

2007

How does your personal experience influence the way you teach design?

I tell my students that there is a way that design can evolve from their own idiosyncratic context. Wherever they are from . . . the product of whatever . . . their yearnings . . . their need to belong . . . their specific urban sensibility . . . their mixed backgrounds . . . I want my students to be conscious of the filters through which they view their work. Their various lineages, strains, and ancestries should show up in their work. This is what gives their work a voice and a vision that will mark it as being unique. What a wonderful gift it is to be from somewhere else. You do not have to replicate what has already been done. Instead of being “cultural tourists,” you can be “cultural nomads.” As such, you want to be fluid, adaptable, and alert to the needs and expectations of others.

Liz Danzico

Interfacing with UX

“Nuna“

Credits: Guri Venstad,

Class of 2013

How interactive are you in interactive design?

I'd give myself an 8 out of 10.

Fair enough, so what is UX?

UX stands for “user experience.” But it's not as clear as that. Acronyms can be intimidating. I was recently asked to give an hour-long talk to a group of highly intelligent people on the difference between “UX,” “IA” (information architecture), and “IXD” (interaction design). Shockingly, most of all to me, it was a pretty riveting talk.

How has UX—or whatever you want to call it—changed since you became involved?

UX, and arguably interaction design, 10 or even 5 years ago meant solving a very local problem—one of interfaces, one of interactions, one of feedback and usability. But today, that isn't the case. We consider those things across platforms and products, across ecosystems. In other words, systems design is much more often a concern than interface design.

How do you teach UX?

Throughout high school, college, and grad school, I waited tables. I worked my way from ice cream scooper to host, to server, to head server by learning how to understand customers and deliver what they wanted, when they wanted it. Through all the missed orders, dropped plates, angry customers, heavy trays, I had to figure out a way to make it all work out.

This idea of understanding customers came up again later during my first job as an information designer. Then again, when I began doing what is now UX, and when I started managing people, I started to think that perhaps the single best way to teach UX is to give someone a job waiting tables. Leave them on the restaurant floor with people who need things. Hungry people with no time. People with families. Mean people. Talkative people. The restaurant is really the best UX boot camp there is.

“unVeil“

Credits: Tyler Davidson,

Class of 2014

What do you expect students to learn?

What a happy customer looks like.

When hiring, what do you want to see in a UX designer?

I want to see someone who gets large systems and small containers, who has empathy, who can focus and scale, who has his or her head in the clouds and hands tinkering with something. And I want to see someone who can put together a focused, clear portfolio that shows not only finished products and services, but sketches and process.

Do you see any crossover between graphic and interaction design, especially UX?

There is a lot of crossover in the considerations of layout and engagement—they just happen across different spaces and tempos, like two songs as part of the same score.

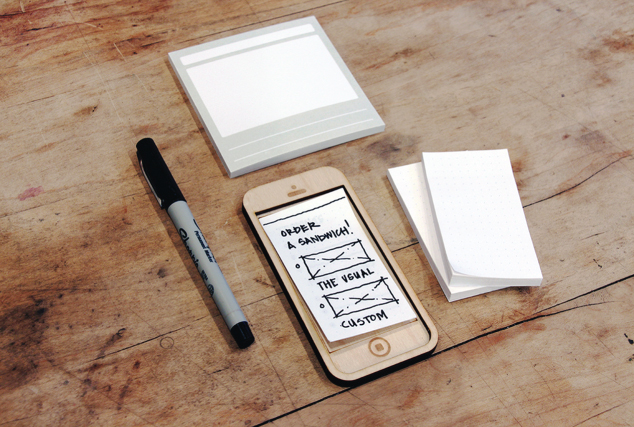

“StickyJots“

Credits: Rachelle Milne, Pam Jue,

Class of 2014

What do you see looking forward in the next few years?

When we think about the future, we have a certain picture in our minds. It's a futurism that was built up in novels, in films, in TV shows, in modern mythology, in urban myth. It was a type of futurism we call “science fiction”—it represents some version of a future. But it's a speculative futurism about what could be. There is little to no thinking about how or when it could be. Designing these types of futures becomes more of an aspiration, perhaps to inspire the design material we currently have to work with.

That was the past: the one in which science fiction was the unattainable future. But today is different. Today, science fiction can be the present. We are designing a pragmatic future. And the time when science fiction was the past has passed. Science fiction is the present. Today, futurism is usable; it's sensible. I think UX's next role is taking on pragmatic futurism.

Allan Chochinov

The Maker Generation

Ice Cream Pint

Designer: Andres Iglesias

You've taught graphic designers how to design and make things in three dimensions. What is the biggest challenge that you've found in bridging the disciplines?

The biggest obvious challenge is that graphic designers are not typically taught to build things with their hands—they seldom have the shop skills or the hand skills required to create the three-dimensional prototypes that are so critical to the creation of innovative products. That said, they often have the drawing skills and, certainly, the illustration skills that are becoming more and more critical to sketching out user scenarios and storyboarding ideas.

What distinguishes a graphic from product designer?

That's an interesting question. I'd say a “love of stuff.” Typical product designers grow up taking things apart, figuring out how they work, making things with their hands . . . that kind of thing. The reality that I've found, however—and this became apparent the very first time that I taught a group of graphic designers a “crash course” in product design—is that though they may not have a history of building, graphic designers seem to have an absolute love of it once you get them started on their own projects. I think the gratifications that come with authorship—and especially with making something with your hands and holding it up in the air—are common to all people, regardless of design specialty. Humans are makers.

What are the necessary base skills or talents that an incoming student to MFA Products in Design must have?

We look for a deep passion for design, creativity, and problem solving. We seek a strong point of view and an acknowledgement that there's work to be done; that the failures and deficiencies of classic practices of design in our world have created as many problems as solutions, and that the consequences of industrialization and mass media have resulted in the systematic destruction of our planet and staggering inequalities between people. We look at artifacts through the lenses of systems, services, stewardship, and participation, and we want to fortify people to go out and create positive change.

Critter Bitters

Designers: Julia Plevin, Lucy Knops

Do you experience more students blurring the boundaries between two and three dimensions? Why?

Well, more than two and three dimensions, actually! I see a blurring between all dimensions—time is often referred as a “fourth dimension”—since most effective design happens over time, and especially when we talk about the explosive growth and importance of interaction design these days. I think there is overwhelming pressure on classic graphic designers to build up their interaction chops and a similar pressure on product designers to make their objects “smart.” We are now entering a period of “the Internet of things”—where microprocessors are embedded in more and more objects and the platforms that tie artifacts together are listening and responsive. There are massive sustainability challenges with such a world, but there are also enormous opportunities.

Pain Killer

Designer: Mohammad Sharaf

Must product designers be fluent in graphic languages, like type? Or is that delegated to others?

We push it pretty hard in the MFA Products of Design program, where we offer two graphic design courses that stress fundamentals like typography, grid, and hierarchy. Remember a few questions back where I talked about graphic designers falling in love with building models if you just give them the chance? Same thing with product folks learning about type. They universally adore it once they're turned on to it.

Collaboration is more common now than ever before. Would you agree that “teams” are surpassing “individual” efforts?

I was just putting together a few slides for a presentation I'm giving next week in which I talk about the requirement to acknowledge contemporary dichotomies in design and design practice. And one of those dichotomies is exactly what you ask: “How do we fortify designers for a world simultaneously demanding individual authorship and collective effort?” We hear over and over that “design is a team sport” and that designers need to be team players. But in this era (and in this cultural moment), there is a supreme belief that “you are your own brand” and that authorship and entrepreneurship are now the coin of the realm. (It's a testament to your prescience, Steve, that you and your cochair, Lita Talerico, named your department “Designer as Author and Entrepreneur.”) In any event, the demands on any designer are growing and growing, and certainly one of them is the ability to produce strong, unique, self-generated work, along with the ability to contribute significantly to group efforts.

The technology is changing so quickly; what do you see as flux and what do you see as static in product design?

I believe the ability to think strategically, empathically, and systemically are never going to change; those are central to any design process and they just make sense. How we bring technology into the mix is changing in a few ways: Where technology used to come at the end—to model with high fidelity or to manufacture an object for production—it is now coming more often at the beginning, since rapid prototyping, or “additive manufacturing,” allows us to build and evaluate things so quickly and with such precision. The other revolution in product design has to do with the overlap of interaction and artifacts I alluded to before. Platforms and languages like Arduino and Processing are allowing designers to embed circuits and smarts into their artifacts with a speed, ease, and affordability completely unheard of just 5 or 10 years ago. There are online communities of code to borrow and Instructables to teach that are vast and deep, and product design is benefiting from the maker movement and online tech communities in ways that are both generous and generative. It's an amazing time to be a designer.

Do you see your MFA program as a model for some more integrated design future?

I hope so. We organize our coursework along three interweaving strands: making grounds design and designers, and deepening the connection to craft and the preeminent role of “the prototype.” Structures inform practice, immersing the students in the information and business structures that make effective design possible: research, systems thinking, strategy, user experience, and interaction/information design. Narratives respond to the reality that design demands stories—through drawing, graphic representation, videography, history, writing, and point of view. We like to imagine that the rubric of Making, Structures, and Narratives is a way to plan for the future as well; that we need to fundamentally “prototype” our possible futures, that we need to structure them based on cultural and marketplace realities, and that we need to understand that knowledge is most effectively spread and shared through the telling of stories.

David Carroll

Students and Surveillance

Antisurveillance Blanket

Student: Lucas Byrum

2014

How did you get interested in surveillance design as a focus of your studies?

I would have to admit that the Edward J. Snowden revelations had a profound impact on my thinking about the role of networked digital technology on our understanding of privacy and security as citizens and consumers starting to realize the magnitude of tracking technologies available to governments and corporations (“the investor-state”) alike. We realized as well how contemporary designers and technologists, who are participating in this architecture of “dataveillance,” have an effect on democracy and capitalism. As an interface or user experience designer, the minute you mock up your first login sequence or integrate social media features, you are doing your part to more fully enable the surveillance state.

I chose Parsons Paris as the ideal venue to launch this course. The language of this topic originates as French vocabulary, and important Parisian thinkers like Michel Foucault situate the topic within an originating milieu.

A silly question: Are the design students who sign up for your course on surveillance design fascinated by whistleblowers, secret agents, and spies?

Not silly at all. My students are part of a generation that was born into the Internet age. They don't know what it's like to live without being connected together through a highly designed digital technology. There's a myth that Millennials (Generation Y) don't care about their privacy because they share every part of their lives on social media. On the contrary, I've found in working closely with them that they are extremely concerned and savvy about how their choices affect their identity as they accumulate social currency.

They are fascinated by how the technology changes our collective behavior and how this is the conceptual basis of surveillance itself. The fashion students, in particular, are interested in how the design and construction of garments can camouflage (there's the French vocabulary again) camera-based, computer vision tracking systems. They understand how there will be a market for privacy in the future and it will probably become a luxury good.

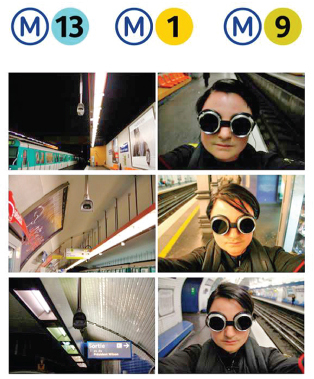

Surveillance Selfie

Student: Diva Helmy

2014

What could motivate a designer to embrace this specialty? Is a desire to expose unethical practices a big part of it?

The ethics of design have been recently focusing on sustainability and how we can make more environmentally and socially responsible products. However, the ethical design movement tends to eschew confronting even more difficult political problems head-on, preferring tactics that will remain friendly to corporate clients who can climb aboard the sustainability bandwagon as a marketing message, for example.

Today's designers see the impact of how connected digital networks can both empower a democratic uprising and topple a cruel dictatorship, or conversely be used by a despot to quash unrest. They see the expanding use of drone warfare. These systems are all designed, and so the role of the designer to confront huge ethical and political issues is quickly becoming the new normal.

Presently, what artifacts, systems, or interventions are designed in response to the demands of the surveillance (and sousveillance) industry?

As designers and users become aware of how their actions on connected devices are datamined for consumer insights and intelligence operations, the market for new tools to manage identity and privacy is just starting to emerge, along with a debate over whether it will become a luxury good.

Some examples of important tools available to monitor and protect your privacy online include browser extensions like Ghostery and Lightbeam for Firefox that help users reveal and control the astonishing number of commercial trackers present on the websites we visit, which allows marketing agencies and customer identity brokers to assemble richly detailed profiles about us through our browsing habits. However, you need to be a serious IT geek or highly trained reporter to be able to use these encryption tools. Here's a great example where we need designers to take an interest in these issues to make protecting our privacy as easy as downloading a song.

In principle, should socially responsible designers refuse to contribute to the development of applications that encourage users to voluntary surrender their privacy?

This will increasingly become a personal decision designers will have to confront as they navigate their career paths. They will need to consider the business practices of the firms they seek employment from and understand how their business models generate the revenue that will supply their salaries. Furthermore, as security and privacy policies are articulated to users through the interfaces in the form of controls and settings, designers can play a very active role in being advocates for clarity to counter the attempts of lawyers to obfuscate these details.

Users are starting to accept that if a Web product is offered to you as free service, then we are actually the product. We do surrender rights to use these products, and in exchange we get to benefit from their affordances without spending our money. But we contribute massive value to these companies through our activity, and the immense return on these investments is showing that companies don't need to be profitable to be worth billions. They only need to show a critical mass of users willing to trade their privacy for a product.

Is it fair to say that the various participatory media (from Wikipedia to Facebook) are huge surveillance infrastructures?

I would say that Facebook is the most powerful and pervasive form of surveillance infrastructure ever created by humankind. It's beyond what Michel Foucault or Jeremy Bentham could have imagined. It's a form of surveillance that we impose on each other on a service increasingly used as a passport that serves as an interchangeable commercial identity. In contrast, Wikipedia is anonymous and a nonprofit. It doesn't have shareholders, so it doesn't need to monetize user identity through data mining and advertising.

Today, how important to a design practice is a constructed criticism of the sociotechnical contexts of the Big Data phenomenon?

Given that design practice is increasingly pushed to deliver “results” based on analytics, Big Data is a big idea that all designers need to confront. People are so easily seduced by numbers because they supposedly represent objective truth. Big Data promises to answer the great questions of humanity by scaling statistical analysis toward a quantum set of correlations. However, what about all the aspects of life that aren't even measurable? How can we verify the claims of Big Data when the algorithms are a trade secret?

More specifically to designers, their practice is increasingly being driven by Big Data mechanics and its promise to provide analytical evaluations of design choices by measuring how designs affect specific user interaction outcomes. Designers will increasingly become accountable to quantitative results rather than mere aesthetic appeal. It's up to us to keep our machines and tools at the service of humans, not the reverse.