Brooms in History,

Tradition, and Lore

No one knows who invented the first broom—probably some poor woman whose Neanderthal husband dragged in a dead prehistoric bird, leaving a trail of feathers and blood all over her nice clean cave. Either way, bundles of twigs, plant stalks, and other natural fibers have been used since ancient times to sweep floors and hearths. Brooms were even mentioned in the Bible (although not in conjunction with witches).

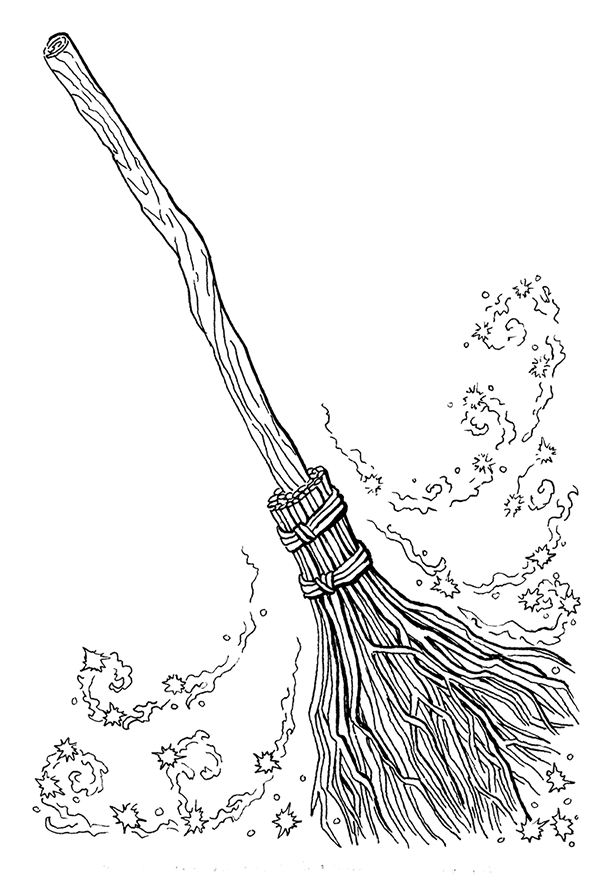

The earliest brooms were known as besoms. They were often made of birch twigs tied to a stick of hazel or chestnut wood. Twigs or straw were bound to the shaft with strips of pliable willow bark or rope. As you might imagine, these types of brooms wore out rapidly and made almost as much mess as they were trying to clean up.

A birch twig besom tied to a stick and bound with strips of willow bark

In Anglo-Saxon England, broom making was a specialty of “besom squires,” but for the most part, people made their own brooms out of whatever materials were available and replaced them as often as necessary.

In the late 1700s, Benjamin Franklin introduced a new plant to the United States: broomcorn. Not actually a member of the corn family, although it can be mistaken for it at a distance, broomcorn is actually an upright grass of the sorghum species (Sorghum vulgare or Sorghum bicolor variety techicum for you science geeks). The stalk of the plant can grow up to fifteen feet high and was the part used to create the brooms that were the precursors of the ones we use today.

It is thought that broomcorn first originated in Africa, then spread to the Mediterranean. Benjamin Franklin was said to have found a single seed on a whiskbroom given to him by a friend. He planted it, and, for a time, it became a garden novelty in Philadelphia and the surrounding area. Then, in 1797, a Massachusetts farmer named Levi Dickinson began to make brooms out of his crop by tying a round bunch of broomcorn to a stick and weaving it into place. His creations caught on, and by 1800, Dickinson and his sons were selling their new brooms across the Northeast.

The next big shift came after the Shakers, a Christian religious sect, figured out a way to make the broom flat and used wire to fasten the broomcorn fiber more securely to the staff. That flat broom is no doubt nearly identical to the one you have in your kitchen today.

Unfortunately, despite the fact that broomcorn will grow almost anywhere and is very drought-resistant, harvesting it for brooms is very labor intensive. More than half of the broomcorn used to manufacture mass-market brooms now comes from Mexico.

However, it is possible to find locally grown and crafted brooms; there are a couple of craftsmen in my area who do it, and the art of broom making is demonstrated every summer at the Farmers’ Museum in nearby Cooperstown, New York.

When looking for a broom to clean your floors, it probably doesn’t matter where it came from or who made it as long as it does a good job. For magickal work, however, it may be worth the effort it takes to seek out one created by hand or make one yourself, either with broomcorn or something else. But don’t worry—I don’t expect you to grow a field of broomcorn!

Brooms have been associated with marriage throughout history, probably because they are a tool that is so tied to the hearth and home. Couples have been “jumping the broom” during handfastings and weddings in various cultures for centuries. During the expansion of the American frontier, when ordained clergymen were scarce, it was common to make a marriage official by jumping the broom in front of witnesses. Likewise, African American slaves, who weren’t allowed by their masters to legally marry, carried forward the folk practices of their homelands and jumped over a broom instead.

Broom magick for cleansing and purification is an obvious purpose that crosses over all cultural lines, and the broom is widely used for protection as well. But these basics are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the lore and uses associated with the common, everyday broom.

You may never look at one the same way again.

real witches,

real brooms:

C. S. MacCath

the common broom and the common rush served similar functions in the pre-modern European home. The broom could be bundled and used for sweeping, while the rush could either be strewn on the floor to keep it clean or bundled and used for a variety of household purposes. So it stands to reason that rituals inspired by these mundane tools would also be similar and centered on themes of cleansing and regeneration.

My favorite of these historical rituals is an Irish threshold rite honoring Brigid at Imbolc, a time of renewal. In County Wexford as late as the nineteenth century, the man of the house would go out after sunset on the eve of St. Brigid’s Day and gather rushes while a feast was prepared inside.

When the feast was ready, he would take the bundled rushes on a sunwise circuit around the house, stopping at the door to say, “Go down on your knees, open your eyes, and let St. Brigid in.” In reply, those inside would do as he commanded and say, “She is welcome. She is welcome.”

Twice more he would take the rushes around the house, and twice more the same call and response would occur at the door. When this part of the ritual was complete, he would bring the rushes inside, put them under the table, and feast with his family.

Afterward, the rushes were used to make Brigid’s crosses, which were hung in every room of the home as a blessing for the coming year.

Many elements of this rite are quite old in Celtic spirituality: the sunwise circuit around the house three times, the crossing of liminal space the threshold represents, the hospitality offered to a saint or god/dess, and, of course, the use of rushes to represent the holy guest. Further, while the context of the historical ritual is Christian, its bones are not, and it easily could be modernized into an Imbolc broomstick rite for two or more people. Here’s an example:

An Imbolc Broomstick Rite for Two or More

After sunset on Imbolc Eve (January 31), one celebrant should go outside, gather twigs and branches, and craft a simple broom while the others prepare a meal inside.

Once the two tasks are complete, the person outside should take the broom sunwise around the house once, stop at the front door, and knock, saying, “The Lady Brigid knocks!”

Those inside should answer, “She is welcome! She is welcome!”

This sunwise circuit around the house and the call and response should be repeated twice more, and then the broom-bearer should come in, place the broom under the table, and feast with the other celebrants. Afterward, they should all take the broom apart and make Brigid’s crosses to hang in their homes as representations of the goddess and as blessings for the coming year.

C. S. MacCath

poet and author • www.csmaccath.com

Broom Lore, Traditions, and Superstitions

As you might expect from something that has been around for centuries and can be found in almost all homes—and that has been associated with witches and magick to boot—there are plenty of superstitions, old wives’ tales, traditions, and sayings associated with the common broom. Some of these make a certain amount of sense, some are just plain silly, and a few of them contradict each other. Here are a couple of my favorites from the ones I gathered in my travels. There are others scattered throughout the book just for fun.

General Broom Lore

- If you drop a broom, you’ll get company soon.

- It is bad luck to move an old broom into a new house. Always buy a new one, and leave the old one behind. (This only applies to regular cleaning brooms, not ones used for magickal work.)

- Placing a small broom under your pillow will keep away nightmares.

- Alternately, you can sweep away nightmares by hanging a broom on the bedroom door and placing garlic under your pillow. (This one might chase away your sleeping partner, too!)

- To bring rain, stand outside and swing a broom in the air over your head.

- Lightning is attracted to brooms, so you can use them as lightning rods to protect your home.

- It is unlucky to buy a broom in August.

- Brooms bought in May sweep family away.

- Brooms should be placed bristle-up (to make them last longer, but also for good luck).

- Sweep toward the fireplace, if you have one.

- If a family moves, it is bad luck to leave the broom behind, even if it is old. (I told you that some of them contradicted others!)

As you can see, there are a lot of superstitions and traditions associated with brooms, and those were only the general ones. Magickal broom lore, of course, is often something completely different, although in a few places they overlap.

Magickal Lore

No one really knows where the association of witches and brooms first began, but there are some interesting theories and suppositions.

For instance, in fertility rites practiced by early Pagans, local women would gather around the newly planted fields. With their besoms between their legs (much like a child on a hobby horse), they would circle the field and hop as high as they could; the higher they leapt, the higher the crops would grow. Some people believe that this was the origin of the “flying” witch on her broom.

There is another theory that brooms were used as a way to hide the witch’s most important tool: the wand. By wrapping birch twigs around the end (which was sometimes carved in a phallic design that would be a dead giveaway to its magickal purposes), the wand could be disguised as a common household implement. Since witches originally were seen as flying on sticks, it makes sense that a witch wouldn’t want to leave a long, carved wand sitting out where anyone could see it.

Also, most witches (or those accused of being witches) were women. Brooms were a symbol of the woman’s role and power in the home. To show visitors that she wasn’t at home, a woman would lean her broom outside the door or push the handle of the broom up the chimney. This may have led to the next step—the belief that a witch could use a broom to fly up the chimney and away.

Early Celtic Pagans connected brooms with faeries, and there is a legend that a witch would go into the forest and ask a faery (or wood sprite) to guide her to the perfect tree from which she could harvest a stick for her broom. Even now, some witches like to carve the face of a Green Man or a forest creature into their broom handles.

It was thought that a broom could be used as a temporary holding place for a spirit. This way, an unwanted entity could be placed inside a witch’s broom and moved to somewhere it could be safely banished or released. Or a spirit could be called to the broom to help its owner with a particular task. (This might have been an element of the story that led to Disney’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.)

broom lore

when a broom falls,

someone will get married

While many magickal tools are either feminine (the chalice or the cauldron, for instance) or masculine (the wand or athame), the broom is one of the rare tools that is a combination of both. The stick part symbolizes the male, and the bristles symbolize the female. Therefore, the broom is a tool that balances both male and female energies. This may be why it has been used throughout history as a part of many handfasting and marriage ceremonies.

There was much negative magickal lore associated with the witch and her broom by the Catholic church. In 1458, a church inquisitor said that believing witches could fly was part of their official beliefs. At that time, witches were seen as flying about on sticks, but by 1580 that had changed to brooms. So I’m guessing disguising their wands as brooms didn’t work…

During the Renaissance, demonologists said that the devil presented witches with brooms, along with flying ointment, to make them move through the air (and often gave them an animal familiar or smaller demon to ride around on it with them). Male witches—sometimes referred to at the time as sorcerers—also rode brooms but were more likely to be depicted astride a pitchfork.

It was thought that witches flew on their brooms to sabbats, where they would meet up with other witches for the purpose of causing mischief. They were believed to call up storms or cast spells on their neighbors.

While there is no reason to believe any of that type of lore, there is some evidence that flying ointment was a real thing (although no doubt it was whipped up by the witches themselves, not given to them by the devil!).

Flying ointment was a mix of grease or lard with various hallucinogenic plants such as belladonna, hellebore, and hemlock. This preparation was too toxic to be taken internally, so it was rubbed on the body (supposedly, the broomstick was used as a phallic tool to apply the flying ointment to the more delicate areas of the body, where it would be absorbed more quickly—an unlikely sounding story to me, but you never know). The herbal ointment then gave the user the sense of flying, or perhaps it aided in trance journeying or astral travel. Needless to say, I don’t recommend that you try this at home!

There was a certain canny practicality in accusing witches of being able to fly. It explained how these women, many of whom were elderly, could travel long distances to meet up with others without being seen. And what woman didn’t have a broom?

There is a more positive spin to the lore of witches flying, however. Many goddesses are depicted as flying through the air—sometimes on brooms and other times on staffs, distaffs (a spinning tool), or on the backs of animals or birds. So it may be that witches have come to be associated with broomstick flight as a reflection of their connection with the powerful abilities of the goddess that most of us worship. Let’s go with that one, shall we?

Broomstick Deities

Many goddesses have been depicted as flying on brooms, but some are particularly associated with brooms as part of their lore. Here are a few of the most prominent ones.

Baba Yaga

In many Russian and Slavic folktales, Baba Yaga was a well-known witch who was sometimes also perceived as a goddess with power over the elements. She had a magickal broom that she used to sweep the path behind her as she flew through the air in her enchanted mortar and pestle.

Baba Yaga was a hag goddess—an ancient magickal crone who was both feared and revered. Although often perceived as a frightening figure with a curved nose, iron teeth, and an unfortunate propensity toward eating children, she would also act as a spiritual guide to those who were brave and clever enough to ask her the right way.

Like many hag goddesses, Baba Yaga was wise and powerful, although not always kind. She was said to guard the doorway to the otherworld and control the passage of the dead back and forth across its borders—and perhaps even the powers of life and death. As she flew through the air, she was often accompanied by crows, ravens, and owls.

broom lore

it is bad luck to loan your broom to anyone, even a friend

Holda

Holda, a Northern European goddess, was said to travel with a pack of hounds. She flew at the head of a gathering of unchristened children and other dead souls in the Wild Hunt, all mounted on brooms. This disquieting group flew through the night, especially between Christmas and Epiphany.

Primarily a winter goddess, Holda was also known as Hulda, Snow Queen, and Mother Holle. She was known for bringing good fortune and prosperity to those with kind hearts—and misfortune to those who were lazy or cruel. (Sounds like an early female Santa Claus, doesn’t she?) Also a nature goddess, Holda controlled snow and fog; when she shook out her feather bed, it caused snow to fall down onto the earth.

Sometimes worshiped as a benign goddess who brings forth children, guards the dead, and spins destiny, she was eventually turned into a more fearful figure. About her, author Judika Illes says:

While some feared Hulda, others, identified as “witches,” still adored her; she travels during the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany bringing gifts of fruitfulness, fertility, and abundance to people. Some fled from her, but devotees of her cult wished to join her night train: the terms “Holle-riding” or “Holda-riding” were synonymous with witches’ flight in Germany as late as the nineteenth century.

Sao Ch’ing Niang

Sao Ch’ing Niang (or Sao Ch’ing Niang-Niang or Saoquing Niang) was a Chinese goddess known as the Lady of the Broom. She lived on the Broom Star, Sao Chou, and was in charge of good weather. It was believed that she could sweep in the clouds with her broom, and farmers would hang pictures of brooms on their fences when they wished for her help either in bringing the rain or taking it away.

Sao Ch’ing Niang was considered a mother goddess and one of the nine “dark ladies” of the Chinese pantheon.

In her book 365 Goddesses: A Daily Guide to the Magic and Inspiration of the Goddess, Patricia Telesco says:

For weather magic, tradition says that if you need Saoquing Niang’s literal or figurative rains, simply hang a piece of paper near your home with Her name written on it (ideally in blue pen, crayon, or marker). Take this paper down to banish a tempest or an emotional storm.

To draw Saoquing Niang’s hope into your life, take a broom and sweep your living space from the outside in toward the center. You don’t actually have to gather up dirt (although symbolically getting rid of “dirt” can improve your outlook). If you like, sing “Rain, rain, go away” as you go. Keep the broom in a special place afterward to represent the Goddess.

Tiazolteotl

An Aztec goddess worshiped in pre-Columbian Mexico, Tiazolteotl was a witch goddess usually shown either carrying or flying on a broom. She was invoked to sweep away her followers’ wrongdoings, and during rituals her priests burned incense and put brooms across the sacred fires.

Also known as Tlazolteotl, she was a dark maiden who inspired sin but also swept it away. Rather ironically, this broom goddess was also a goddess of filth. She was also the matron of midwives and female healers, as well as weavers. While most often depicted as a statue of a naked woman squatting in the throes of labor, she is also pictured as riding on a broom (still naked, except for a hat), accompanied by ravens, owls, and bats.

real witches,

real brooms:

Judika Illes

the russian witch-goddess Baba Yaga doesn’t ride her broom—she uses it for spellwork. Baba Yaga drives a giant mortar, steering with the pestle while simultaneously using her broom to magically sweep away her traces, so that no one can tell where she’s been and what she’s done. Likewise, although I also use brooms for cleansing and prosperity spells, my very favorite broom spell is intended to ensure safety and privacy by keeping harmful people from ever darkening your doorway again. The trick is to first salt and then sweep away their traces.

It’s a simple spell, requiring nothing more than a broom, some salt, discretion, and steely nerves. You must also be wearing clothes with at least one pocket. The catch is that the spell must be cast during what is hopefully this person’s last visit.

Discreetly fill your pockets with salt in anticipation of your unwanted visitor’s departure. As he or she departs, walk alongside, just a discreet step behind, sprinkling the salt—even more discreetly—behind your unwanted guest. You want to sprinkle the salt gently between your fingers, rather than tossing it or otherwise attracting attention to it. Walk with your guest, sprinkling all the way, until you reach the boundary of your property. Say your farewells and watch your visitor leave. When you are absolutely sure this person has left, go get your broom. Now sweep the salt away, always sweeping in only one direction—the direction from your door out to the boundary. Simultaneously murmur your target’s name, willing him or her never to return.

On another note, brooms, to me, are also emblematic of witches. In the days before pentacles were so openly worn, a brooch or charm in the shape of a broom was a discreet announcement that one just might be a witch. I have several of these and am frequently pleasantly surprised by the winks and nods I receive from passersby who notice and understand.

Judika Illes

author of The Encyclopedia of 5000 Spells,

Pure Magic, and The Element Encyclopedia of Witchcraft