This is a work of fiction. While the general outlines of history have been faithfully followed, certain details involving setting, characters, and events may have been simplified.

Red Elk, chief of the mighty Blackfoot Indians, stood at the edge of a high cliJBF and watched the snakeHke column of a wagon train far below. His expression was fierce as he tried to contain his fury and frustration at the presence of white intruders in the lands that had once belonged to the Indians. Stretching out his arms, he looked up to the heavens, and in a voice bursting with emotion, he cried out:

"By the gods above and by my ancestors, I swear we win destroy the white men who intrude upon our landsl Soon bloody scalps will hang from the belts of all red men. I, Red Elk of the Blackfoot, have been called by Thunder Cloud of the Sioux to meet with him in Dakota. There we will also meet with Big Knife of the Cheyenne to plan ways to work together in trampHng the white man into the dust."

With great agility. Red Elk leaped onto his horse and galloped away, followed by his war chiefs and braves, whose faces mirrored the feelings of their chief. The wagon train they had seen heading west would be the

last to pass through unharmed. After the meeting of the chiefs in the Dakota Territory, white men would be eliminated from Indian lands once and for all.

The wagon train that moved slowly across the rugged Rocky Mountains, en route from Fort Shaw in the Montana Territory to Fort Vancouver in the Washington Territory, bore a strong resemblance to the trains that had made similar journeys more than two decades earlier. For one thing, the canvas-covered wagons, filled with food supplies and household goods, were similar, as were the teams of sturdy workhorses that pulled them. Also, the men and women who drove the wagons, most of them young and self-reliant, bore a striking resemblance to the earlier pioneers, and the rate of travel in the mountains—approximately ten to fifteen miles each day—was about the same.

But the big difference of this wagon train was the presence of the blue-uniformed troop of one hundred horsemen, members of the Eleventh U.S. Cavalry, who escorted the train. The troops, suppHed by Colonel Andrew Brentwood, commander of Fort Shaw, were veterans of the recently ended Civil War, as well as the conflict in Montana the previous month with the Sioux Indians. The soldiers carried rifles and cavalr>' sabers, and they acted as deterrents to those who otherwise might have found the wagon train a tempting target.

Members of the wagon train included army personnel and their families, as well as a few immigrants from the East, who had traveled to Fort Shaw in Montana by way of steamboat on the Missouri River. Without the army escort, these wagon train members would have faced raids by the Indian tribes of the mountains as well

as by bands of outlaws, who preyed on so many immigrants traveling west.

Clarissa Holt, a scarf tied over her red hair to protect it from the sun, was on the seat of her wagon. She was tall and statuesque, qualities that couldn t conceal the fact that she was a few months* pregnant. As she drove the vehicle with practiced ease, she reflected that she was enjoying herself enormously. She had made a journey like this just a few years earUer, when, as a widow in Philadelphia whose husband died fighting in the Civil War, she had traveled to the Washington Territory in what came to be called "the cargo of brides." Her friends on that journey had found new lives and husbands for themselves in the West, and she had found happiness when she had fallen in love vdth and married Toby Holt, son of the legendary Whip Holt, the mountain man and guide whose name was synonymous with the opening of the West.

Clarissa knew that in years past, when Whip Holt had led the wagon train across the Rockies, the pioneers had only themselves to rely on, and she had heard corroborating stories from Toby's mother, Eulalia, about the adventure-packed, dangerous travel that the settlers on the first wagon train to Oregon had endured. Now, in the 1860s, the trails were well traveled, many army posts were established, and wagon trains frequently moved in the company of army troops. Thus, overland travel in the West held fewer dangers, though it was no less arduous, especially in the mountains. Only the establishing of the transcontinental railroad, which Toby Holt was working on, would make travel through the mountains seem easy.

Forthright and blunt, Clarissa told herself that her happiness would be complete if only Toby were with her right now, sharing the pleasures of this wagon train

journey in the pleasant autumn weather. But Toby, whose exploits were winning him a measure of fame almost as great as that of his late father, had been summoned to Washington City to confer with General Ulysses S. Grant, the chief of staff of the United States Army. The exact nature of the meeting was secret, but Clarissa knew it had something to do with the growing problems with the Indians.

Before heading east, Toby had insisted that his wife leave Fort Shaw, where she had stayed while he worked on the survey of the railroad in Montana. She was to travel with the small wagon train of army men and their families and join Toby's mother and stepfather. General Leland Blake, at Fort Vancouver in the Washington Territory, where General Blake made his headquarters as commander of the Army of the West. Clarissa was carrying their child, and Fort Shaw, Toby had decreed, was too much of a frontier post for a new Holt to begin life there.

Clarissa and Toby had been married only a scant six months, and in that time they had experienced a number of trials. Toby's proposal to Clarissa the previous spring had been sudden, and she was conscious that he had made it not so much out of love for her as out of a sense of bewilderment and distress at events in his own life. First, there had been the violent death of his estranged former wife. Then he had lost his father in a tragic rockslide in the Washington Territory. They had been close as few fathers and sons are, and Toby was thrown completely off balance. To further complicate his life, he had been infatuated with Beth Blake, who married his best friend. And to top it off, Toby's mother, Eulalia, married again. Of all the men who could have become his stepfather, Toby couldn't have wished for anyone more worthy than

General Lee Blake, but nevertheless, he had had difiB-culty accepting his mother's remarriage.

Now, however, all this unhappiness seemed to be fading. Toby had come close to losing Clarissa in the recent battle with the Sioux in the Montana Territory, and this made him realize how much he loved her, that she was the one person in his life who really mattered. Clarissa fervently believed that now their love could shield them from all difficulties—past and future.

A move on the seat next to her aroused Clarissa from her reverie, and blinking, she diverted her attention to Hank Purcell, the sixteen-year-old orphan she and Toby had informally adopted in Montana. Tall for his age, Hank was thin, with sun-streaked hair and freckles on his nose. At the moment he was petting Mr. Blake, Toby's German shepherd, who sat beside him and was accompanying Clarissa and Hank to Washington, acting as their protector.

Hank's accuracy as a marksman with rifle and pistol was remarkable, and the Holts had placed him under their wing to prevent him from becoming a professional gunslinger. Indeed, he was such an expert shot that he had already become the wagon train's principal hunter.

Clarissa was horrified when suddenly she saw that Hank had his rifle raised to his shoulder and was squinting down the barrel.

"Hank!" she exclaimed. 'What on earth do you think you're doing? You know very well that the cavalry escort has forbidden anyone to shoot a gun from the wagons. Put down that rifle this instant!"

Hank gave a deep sigh, the reaction of an adolescent to the restrictions of adults. He lowered his rifle, then furiously brushed the bridge of his nose, as though trying to rid it of the freckles that dusted it. "I had the

heftiest bighorn sheep you ever saw lined up in my sights," he said regretfully. "In another half-minute, I would have squeezed the trigger, and we'd have had a real treat for supper tonight."

Clarissa averted her face so he wouldn't see the humor that welled up in her green eyes. Toby had been right when he had told her, "That boy is a natural with a gun. He'd rather shoot than eat or sleep."

He was sensitive, too, and inclined to brood over grievances—probably because he was so conscious of being alone in the world. He now looked very unhappy, having been denied his sport, and Clarissa felt she had to distract him.

"I'm sure I'd have enjoyed the mutton," she said. "But to tell you the truth, I'm looking forward to that antelope you shot yesterday." Actually, she had never eaten antelope meat, which she had heard was tough and stringy, and she wasn't looking forward to it at all.

Hank was self-disparaging. "Shooting an antelope," he said scornfully, "ain't what I call fancy shooting."

Clarissa, a former schoolteacher in Philadelphia, had spent months at Fort Shaw teaching Hank correct En-ghsh. Occasionally, however, especially when he was excited or irritable, he forgot his grammar, which was one reason Clarissa was anxious to enroll him in school once they reached Fort Vancouver. But for the moment she had other matters on her mind. "You brought down three animals in less time than it takes to tell it. I'd call that very fancy shooting, indeed," she said with finality. "Besides, I've been anxious to try out my father-in-law's recipe for antelope meat."

The boy was excited. "One of Whip Holt's own recipes? Gollyl If it ain't—I mean, isn't—a secret, maybe you could teU it to me."

As Clarissa had hoped, his failure to shoot the bighorn sheep was forgotten. "You may watch when I make the dish," Clarissa repHed sweetly. "I learned the recipe from my mother-in-law." As a matter of fact, she had indeed been told the recipe by Eulaha, who had laughingly explained at the time that she had no intention of ever preparing the dish, having eaten enough antelope steak on the original wagon train jovmaey to the West.

"The only secret of preparing antelope," she said, "is that you cut the meat into small pieces and put them into a pot with some bones and a Httle water. You don't add the vegetables until later. Then you cook the meat very slowly over a low fire, and you let it bubble away for at least twice as long as you'd cook beef. Antelope is tough unless it's cooked for a very long time, even longer than buffalo meat."

Hank looked grateful. *T11 remember that," he said.

The atmosphere was far less tranquil on the seat of the next wagon in the line. Holding the reins of the team of four horses was Rob Martin, Toby Holt's closest friend and partner in laying out the Northern Pacific's route for a transcontinental railroad. Tall and soHdly built, with a strong, square jaw and thick red hair, Rob was the son of Dr. Robert and Tonie Martin, who had traveled to Oregon in the original wagon train. Rob had grown up in the Portland area, and he and Toby had known each other all their hves. Now, however, Toby was en route to Washington City and an unknovm destiny, while Rob was heading for Fort Vancouver and then on to Cahfomia. He had agreed to oversee the construction there of the Central Pacific Raihoad, which was scheduled to meet the tracks being laid by the Union Pacific somewhere in Utah.

Seated beside him on the wagon seat, her long blond

hair tousled, her blue eyes icy, was Rob's wife, Beth, the daughter of Lee and Cathy Blake. Many old friends of her parents claimed that she bore a startling resemblance to her mother, but few people had ever seen Cathy be as moody and temperamental as Beth. Indeed, the young woman had suflFered terribly when her mother had died with Whip Holt in the rocksHde. Missing Cathy so much, Beth had become nearly hysterical when her father had married Eulalia Holt, and Beth's attitude—toward life in general and Eulaha in particular-had grown worse and worse.

"Did you actually tell me," she suddenly demanded, "or did I just dream about that gold mine you and Toby found in Montana? Weren't we supposed to be financially independent for the rest of our lives?"

"All I know," Rob said patiently, used to her sarcasm, "is that when Chet Harris and Wong Ke took over the management of the mine for us, they told Toby and me that we'd be comfortable for as long as we Hved. What they mean by comfortable, and what you mean by financial independence, I don't know. I'm inclined to accept the estimates of Chet and Ke because they made their own fortunes during the big strike in Cahfomia back in forty-nine, and they obviously know what they're talking about."

"If we have the money to do what we please, then I see no reason to hold back," Beth said flatly. "We can buy a house in San Francisco, and I can Hve there while you're out in the Sierra Nevada, overseeing the construction of the raihoad."

He sighed heavily. "Yes, Tm smre we could afford to buy a house there, but why you'd want to live in San Francisco, where you don't know a soul, is beyond me. I

think you'd be much better off living with your family in Fort Vancouver until I finish my assignment."

Beth replied in a low, intense voice. ''Nothing on earth will force me to live under the same roof with that womani"

Rob arched an eyebrow. "You mean Eulalia?"

"Correct/* she replied angrily. "Eulalia Holt Blake. You won't beheve this, Rob, no matter how many times I tell you, but I saw her expression when my mother and her husband died in that terrible rockslide. She was determined not to be a widow. She wanted my father's rank and social position, and she went after him right then. She played all her cards right, presuming on a lifelong friendship and demanding his sympathy. Well, she got him, and she's Mrs. Lee Blake now, but that doesn't mean that I'm going to show approval by spending even a single night under their roof."

Rob looked with unseeing eyes at the rugged, snow-covered peaks on both sides of the narrow valley through which the wagon train was traveling. Tugging his broad-brimmed hat lower on his forehead, he sighed. *'By this time," he said heavily, "you know I don't believe that. I've known Eulaha all my hfe, and in my opinion she's a fine woman—a damned fine woman."

**You like her because you and Toby are so close," she said. "But I know what I know."

The unending argument led them nowhere, and once more Rob tried to sort out the situation. He recognized that his obstinate, independent wife had been badly spoiled as a girl by her parents. But, as he realized aU too well, their problem went beyond that. After her father s remarriage, Beth had become increasingly remote, faiHng to respond to his lovemaking; her indifference had cooled his passion so that he was rarely aroused.

The lack of ardor shown by one was felt by the other, and the vicious cycle was growing increasingly worse.

Rob, who loved his wife, was in a quandary. If necessary, he knew he could exercise his prerogatives as head of the family and insist that she obey him. But such a course was certain to cause more problems than it would solve. Not only would Beth be miserable if she was forced to live with her father and stepmother, she would also cause them great unhappiness. Worst of all, the gulf that separated her from her husband would become wider and deeper, and it might not be possible for them ever to bridge their diflFerences.

He wondered whether he might to wiser to give Beth her head in the hope that the passage of time would soften her opinion of her stepmother. Once she was cured of that strange fixation, he reasoned, all her other troubles might solve themselves.

"Suppose I were to leave this whole matter in your hands?" he said. "What would you do?"

Beth suddenly brightened. The prospect of having her own way improved her mood -instantly. Once again she became the lovely, vivacious Beth Blake Rob had known when he first married her. Her smile was radiant, and her eyelashes fluttered as she looked up at him. "First of all," she replied sweetly, "you and I will leave Fort Vancouver as soon as the wagon train gets there. We'll hire a carriage, load up our belongings, and go directly to your family in Portland."

"Hold on," he said, raising a hand. "If you mean that you wont even spend a night or two under your father and stepmother's roof, I've got to draw the line. You have no call to insult them that way. They wouldn't understand what you were doing, any more than I do. I'll compromise with you, Beth, and we'll find some-

place where you can stay for the six to twelve months that I'll be off building the Central Pacific hues. But I won't even consider the matter unless you agree to pay at least a token visit to your father and Eulaha/'

Beth was faring better than she had anticipated and felt sure a real victory was within sight. Nevertheless, she hated to concede even a minor point and could not help replying between-clenched teeth, "Oh, all right. I suppose I can tolerate watching that conniving woman weave her spell around my father for a day or two/'

"That's very noble of you, I'm sure," Rob said.

She ignored his comment. "After that, I'll find a place in San Francisco. The Sierra Nevada aren't all that far away, and you could come down from the mountains and join me in the city whenever you've had enough of primitive living."

**I wouldn't say that San Francisco is an ideal place for any lady to settle in," he said. "Yes, we spent our honeymoon there, but that was different. For a woman on her own, it's a wild, wide-open town."

"Those stories are exaggerated," Beth said impatiently. **The vigilante committees and the army garrison at the Presidio keep order. After all, any number of prominaat people live in the town with their families—Chet Harris and Wong Ke, just to mention two who come to mind."

He was dubious but began to weaken. *1 don't know/' he said. "This will require some thought. I must admit, I like the idea of having you fairly close whenever I can get away from my work for a few weeks or so. But I'm not sure you'd be safe living in San Francisco alone."

"What harm could possibly come to me?" she demanded. "After all, I came to know a great many people there when Papa was in command of the Presidio.

What's more, the Harrises and the Wongs can always act as my chaperons."

Chet Harris had crossed America on the original wagon train to Oregon as a boy and had become a multimillionaire, an industriahst and financier responsible for much of the development of cities in CaUfornia and Oregon. He was also the stepson of a retired United States senator from Oregon, and there were few people anywhere who had his respectability. Wong Ke, who had immigrated to America from China, had met Chet in the gold rush of 1849 in California, and they had become partners and close friends. Ke and his wife, Mei Lo, were also exemplary citizens of San Francisco.

Perhaps, Rob thought, San Francisco was the answer. *'When we reach the city," he said, "Fve got to see Chet on business relating to our mine. Suppose I sound him out then and get his advice?"

"What a good idea," Beth said demurely. She felt certain that Harris and his charming wife, Clara Lou, would welcome her to San Francisco. She would not be forced to live under her father's roof, with Eulalia Blake as mistress of the house.

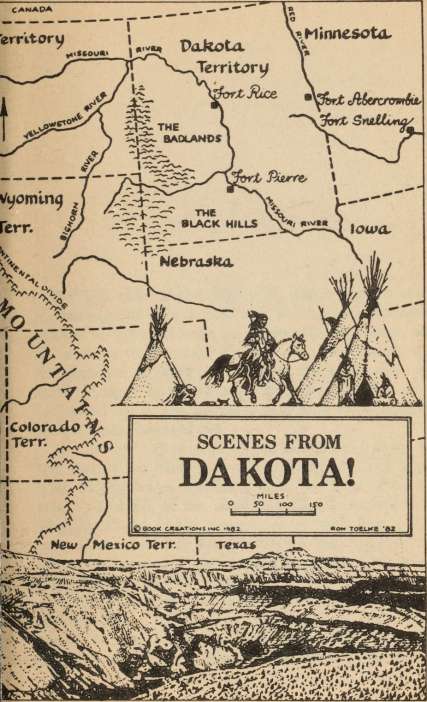

A sense of uneasiness pervaded the Dakota Territory, a land of vast prairies and rugged hills, of hunting grounds for buffalo and elk, antelope and deer. A land larger than the Washington Territory and Oregon combined, the sparsely populated Dakota Territory was now to be the meeting place of three of the most fearsome Plains Indian tribes, who were making plans to engage in war against the United States.

The chiefs and warriors of the Sioux, the Blackfoot, and the Cheyenne were gathering for a meeting in the western part of Dakota, in an area known as the Bad-

lands, a region of deep gorges and high buttes, rugged hills and huge rocks with jagged, strange shapes. In spite of the western migration that had brought settlers all the way to the Pacific Coast and to the lands that lay between it and the heavily populated Middle West, there were almost no white men in the Badlands. The soil was as unproductive as the vistas were bleak, and the temperatures, ranging from blistering heat in summer to numbing cold in the winter, did not encourage settlers to sink roots there.

It was toward the Badlands that Thunder Cloud, the distinguished, shrewd leader of the mighty Sioux nation, the most numerous and powerful of the Great Plains tribes, headed after his warriors had suflFered a severe defeat in Montana at the hands of the Eleventh U.S. Cavalry, commanded by Colonel Andrew Brentwood. It was also in the Badlands that Thunder Cloud had decided to hold this meeting of the three Indian nations, and he had sent out Sioux couriers to notify the Black-foot and the Cheyenne.

Thunder Cloud, wearing his distinctive, feathered warbonnet, rode at the front of the Sioux procession. He was a large man of middle age, with a powerful, broad chest and strong arms, and he carried himself with a natural dignity and grace that belied his years. No one seeing this proud, fierce-looking chief for the first time would have guessed that he had at last met his match and had been driven from Montana.

Behind him, some mounted on horses, some treading on foot, were hundreds of warriors, the survivors of what had been the so-called invincible corps of braves. Colonel Brentwood and his cavalrymen had taught the warriors a bitter lesson: He who attacked settlers and

destroyed or stole their property would pay the consequences.

Dazed by their defeat, the braves knew only that they retained faith in Thunder Cloud. Where he led, they followed. So they marched deeper and deeper into the Badlands, the atmosphere becoming increasingly eerie. The hunters who had volunteered to go out into the Plains in search of game were glad to have something to get their minds off the unreUeved gloom.

Living up to their proud boasts that they could make themselves at home anywhere, the Sioux set up their tepees of animal sldns, made their campfires, and for the first time since they had been forced to flee the Montana battlefields, they enjoyed hot food instead of having to rely on jerked beef and parched corn. They roasted the elk and buffalo the hunters had brought in that day and ate hungrily. Then, sitting around the campfires, they gazed at the vast starlit sky above the Badlands.

Twenty-four hours later, Sioux scouts sat their mounts on the highest hills near their bivouac and watched the approach of another similar force heading into the Badlands from the north. Mounted on horseback, these braves were armed with bows and had quivers of arrows slung over their shoulders.

When the strangers drew nearer, one of the scouts broke the silence. "Blackfootl" he said.

That identification explained why the new arrivals looked so self-confident and held their heads so high. The Blackfoot were the scourge of the northern Plains, and none of the neighboring tribes dared to stand up to them. As the Blackfoot poured into the area and set up their camps, the Sioux, sensitive to their recent defeat, kept their distance, as Thunder Cloud had instructed them. The chief knew that his warriors were hot-tern-

pered, and because they were unafraid of the Blackfoot, fights could break out at any signs of condescension or ridicule on the part of the other Indians.

No hostile incidents, however, marred the meeting of the two nations, not only because of the common sense of Thunder Cloud but also because of that of Red Elk, the chieftain of the Blackfoot. Many years younger than Thunder Cloud, he was nevertheless just as sensible, and he, too, instructed his braves to keep to themselves.

As it turned out, the warriors of the two nations got along very well, and after two days they were hunting and fishing together, eating their meals with each other, and even sharing evening campfires. The Sioux and the Blackfoot, to their mutual astonishment, discovered they had many attitudes in common, not the least of which was a burning hatred for the people of the United States. These intruders who migrated from the more settled parts of America, bringing their wives, children, and household belongings with them, were indifferent to the fate of the Indian nations and settled in the sacred hunting grounds of the tribes, literally taking food out of the mouths of the Indians. The braves agreed that this situation could not be allowed to exist any longer.

Eventually the two groups were joined by a third tribe, the ferocious and defiant Cheyenne of the south-em Plains. Arrogant and proud, the Cheyenne recognized no authority other than their own. They were so suspicious, even of other Indian tribes, that when their leader, Big Knife, arrived to confer with Thunder Cloud and Red Elk, he was escorted by a hundred heavily armed warriors.

The outraged Sioux refused to admit Big Knife and his entourage into the encampment, and a heated altercation followed. A fight that would have ruptured the

peace and destroyed the carefully laid plans of Thunder Cloud was averted when the Sioux chieftain heard raised voices and, with Red Elk following him, emerged from his tepee to see what was amiss.

Raising his voice. Thunder Cloud bellowed like a wounded bear. "You are now brothers at this council! He who raises a hand against his brother will die the torture death of the Plainsl"

Order was restored with difficulty, and the Cheyenne bodyguard permitted their chieftain to accompany the other leaders only because they were reassiu-ed by the presence of the Blackfoot leader in the Sioux camp.

Once Thunder Cloud was alone with his two visitors, he led them to a small fire burning behind a huge boulder that concealed all three of the leaders from their followers. Seating his guests with due ceremony, he Hghted a peace pipe, and once it was drawing freely, he passed it to Big Knife, who puffed on it and handed it to Red Elk.

Thunder Cloud made a gracious welcoming speech, and Red Elk replied in kind, but after the way of Indians, his address was longer and more elaborate. Then it was the turn of Big Knife, who spoke interminably.

Thunder Cloud remained outwardly serene, his face and manner in no way indicating his inner tensions. He was an old hand at conferences with chiefs from other tribes. He had been holding such meetings for many years, and aware of the Indians' love of ceremony, he was resigned to wasting a great deal of time before he could get down to business.

Finally, however, the blessings of the gods who guided the destinies of all three nations having been duly invoked, he proceeded to the subject that had impelled him to caU the conference. "My brothers," he

said, "I will not be satisfied until every river that runs through the Great Plains, the northern Plains, and the mountains is red with the blood of the white settlers."

Red Elk nodded. "I do not blame you for feehng as you do, my brother,'* he said. "It is not easy to suffer humiliation by the U.S. Cavalry."

Big Knife grinned insolently. "He who has been bitten by the snake with a rattle in its tail," he said, "is forever afraid when he hears a rattle."

Thunder Cloud looked at him calmly. "The Cheyenne are fortunate," he said, a hint of sarcasm in his voice. "They are luckier than their brothers of the Sioux and of the Blackfoot. Unlike the lands of the Sioux and of the Blackfoot, the hunting grounds of the Cheyenne are still filled with game, their rivers are still well stocked with fish, and many beaver, fox, and bear provide coats of warm fur for the warriors, squaws, and children of the Cheyenne when the weather is cold."

Big Knife was vulnerable to the ridicule of the older leader, and his eyes blazed angrily. "Thunder Cloud," he said, "well knows that the Cheyenne have suffered grave injustices at the hands of the white men, just as the Sioux have suffered them."

"Ah," the older man said mildly, "then you are willing to consider joining forces with the Sioux and the Blackfoot to stop these injustices and to right the wrongs that have been done to our nation."

**My warriors and I," Big Knife said stridently, "have marched for many days to explore with you the possibilities of such a imion."

"Then hear what I say," Thunder Cloud told him, "and do you Hkewise, Red Elk. This is a time for truth. The soldiers of the United States Cavalry are superior to our own warriors. They are not better fighting men, but

they are better equipped. They are armed with firesticks. Our bows and arrows cannot compete with them, just as our wooden lances are no match for the steel of their sabers. Their horses are big and strong, and although they are not as swift as our mounts, they are less skittish during battle. The armed might of the white men grows stronger with each passing day, and the troops who wear their uniforms are also growing in numbers. The Sioux met their cavalry in battle, and we were vanquished. Only because our gods took pity on us were we able to escape with our lives so that we may fight again."

Red Elk's brow was furrowed. "What must we do, my brother, if the Blackfoot are to avoid the disasters that struck the Sioux?**

*1 do not need to have the vision of a medicine man," Thunder Cloud said solemnly, "to foretell the futmre. I see the day coming when there will be no hunting grounds left for the Indian nations. Already in the eastern portions of what the white men call the Dakota Territory, farmers are growing wheat and com. They are encroaching more and more on our hunting grounds. The great herds of buffalo, as well as elk and moose, antelope and deer, that have provided food and clothing and tepees for our people for untold time are beginning to vanish. The white man takes skins of beaver to make hats for men and coats for women, and there are no beaver left in our rivers. The white men are like a great plague of locusts who denude our lands."

"The Cheyenne vidll take action to stop them!" Big Knife cried.

Thunder Cloud shook his liead sadly. **The Sioux have already acted and have suffered a terrible defeat," he said. "Are the Cheyenne mightier and stronger than the

Sioux? In your heart of hearts, you know they are not. Are the Blackfoot stronger?^

Red Elk shook his head. "That is what my warriors like to think when they drink much whiskey," he said, "but they know that they are not the equal in battle of the Sioux.**

Having established his point, Thunder Cloud drove home his message. "We must lay aside our ancient feuds. The Sioux and the Blackfoot and the Cheyenne must stand together and act as one nation against the white man's soldiers. We will overwhelm them with our numbers, and even though their weapons are superior to ours, they will not be able to stop our warriors. For every brave that falls to the white man's guns, we will be able to send in another one to take his place, until at last we have driven the white man from our lands. But time is short, my brothers. Either we stand together immediately, or the settlers will drive the last of our game from our hunting grounds I"

Big Knife scowled and shook a menacing fist. "Our warriors must form an alhance and together drive the intruders from our lands."

"You are right," Red Elk said. **We must band together against themi"

Thunder Cloud breathed more easily. Each chieftain believed he had originated the idea of forming an alhance of Indian nations, and therefore each would see to it that his braves accepted the plan.

"In order that there be no strife among us," Thvmder Cloud said, "let each nation be commanded by its own chief. But we will act together, and we will take a firm stand against the armies of the white men who would rob us of our heritage 1"

Now the warriors of the three tribes were summoned

to a meeting, and the chieftains presented the plan to them, saying that they would go to war the following summer. In the meantime, the various tribes would return to their villages to wait out the coming winter and to prepare themselves for war. The men were to make more arrows and other weapons, and the women were to make plenty of pemmican and parched com. In long, fierce speeches one theme was stressed repeatedly: Havoc would be created for the white man, and when the war ended, the hunting grounds of the West once again would belong to the Indians, who had called them their own for hundreds of years.

As the chieftains anticipated, the braves voted unanimously to fight together. The fate of white men in the Plains of the West and in the Rocky Mountains appeared to be sealed;

A silence engulfed the assemblage as the chieftains engaged in the ritual of exchanging wampum, strips of leather that had been bleached white in the sun and studded with beads and shells. Now the treaty of alliance was binding, and the Sioux, the Blackfoot, and the Cheyenne had become blood brothers. When they regrouped in the summer, all of them would be dedicated to the elimination of settlers from the regions they considered their own.

For the first time in history, the three most powerful and warlike tribes of the American West were at peace with each other. As the ceremonies were concluded, and wild, triumphant war whoops rose into the air above the Dakota Badlands, the future appeared as bleak for the army and the settlers as the landscape itself.

The United States Army had grown so rapidly during the Civil War that its headquarters were located in a

number of buildings in Washington City. At the end of the war, men had been demobilized by the tens of thousands, but such were the pecuHarities of bureaucracy that the headquarters remained overcrowded.

Nowhere was this more evident than in the oflBcial building that housed the secretary of war and the chief of staff. General Ulysses Simpson Grant, the highest-ranking uniformed officer in the service of his country, occupied a suite of small, cramped rooms. His private sanctum, adjoining a tiny conference room, was barely large enough for his desk and two visitors' chairs. A gruff, biurly man with a dark, full beard. General Grant showed his usual disregard for army regulations by leaving the top buttons of his tunic unbuttoned. This was admittedly sloppy, but as the general confided to his intimates, at least he was comfortable and was not in danger of choking.

There was a knock on his oflBce door, which the general answered with a loud command to enter. It was Toby Holt. Lean and angular like his late father, Toby appeared to be made only of sinew and muscle. His hair was sandy colored, his eyes were pale blue and penetrating, and his rugged appearance was that of a man who spent much time in the wilderness. Only his jacket, necktie, and brown serge trousers suggested he was also comfortable with civilized ways.

As Toby entered. General Grant grinned, removed an unlighted cigar stub from his mouth, and stood, extending one hand in greeting. Toby, who had spent nearly four years in the Union Army during the Civil War, had to prevent himself from saluting.

"By God, Holt," the general boomed, "youVe the spitting image of your father. Anybody who knew Whip Holt would know at a glance that you're his son."

Toby often had heard the same comment and invariably was pleased by it. "Thanks very much, sir," he said.

Grant waved him to a chair on the far side of his desk and peered at him from beneath bushy eyebrows. **When was the last time we met?" he asked.

Toby started to speak, but General Grant held up a silencing hand. "No," he roared. "Don t tell me. Let me figure this out for myself. I've got it. The Virginia campaign in sixty-four. You were a troop commander in the Eleventh Cavalry, and you led a charge that helped break the back of the Confederate Cavalry.*'

Toby grinned at him. "You have a remarkably good memory, sir," he said. "You met scores of officers every day."

"Not all of them were cited for valor the way Andy Brentwood cited you, young man," the general said. "I recall you very distinctly. Weill" He picked up his cigar, jammed it into his mouth, and rolled it from one side to the other. **You seem right for the task we have in mind. What do you know about what we have in store for you?"

"A little, sir,** Toby told him. "Colonel Brentwood informed me that there was a serious Indian problem in Dakota and that some of my qualifications might be useful. He also mentioned that my experience in laying out a railroad route for the Northern Pacific might come in handy, as well."

The general guffawed. **'Might be usefull'" he echoed. "'Might come in handyl' I don't know who's guilty of understatement, you or Brentwood. Maybe it's just Andy's dry sense of humor, which I've always enjoyed, but the fact of the matter is that your qualifications are indispensable and your services are essential."

The general paused. "Now, to take things one at a

time. I suppose you know that the Army Corps of Engineers has already surveyed the routes for raihoad lines across the Dakota Territory. Theyll join with the routes that you and young Martin have already surveyed in Montana and Washington.'*

**Yes, sir, I was told that the army was doing the job in Dakota.*'

Grant nodded. "Obviously,** he said, "once the railroad begins to operate, the United States is expecting a great wave of immigration—a veritable tidal wave—into the Dakota, Montana, and Washington territories. It's an exciting prospect. There are thousands and thousands of acres out there of prime land for the establishment of farms. There's equally vast acreage for grazing. Not to mention the minerals available in the mountains and the development of a tremendous lumbering industry that's already under way in Washington."

**Yes, the potential is certainly there," Toby agreed.

The army's chief of staff smiled grimly. "Right now, however, it's only a potential," he said. "So much could still go wrong. But I'm getting ahead of myself." Briskly he continued, "If you agree to come to work for us, one of your first duties will be to travel from one end of Dakota to the other and inspect the engineers' survey routes. You'll be accompanied by a party of army engineers, including oflBcers who've actually worked on the surveys, and theyll be under strict orders to accept your recommendations without question. If there's anything you don't like, just say so. If you want to change the route, that will be your privilege. All this will be spelled out, not only in your orders but in the orders being sent to the commanders in the field."

**You*re giving me a tremendous responsibiHty, General," Toby said. *T hope I can Hve up to it."

"Fin sure you can—and will,** Ulysses Grant told him. **The routes you and Martin charted in Washington and Montana have met with extraordinary approval by members of Congress, and this Dakota link, which has already been roughly mapped, should be nothing compared with those in the other territories. No, it's only a matter of time now before there's a railroad being built in the north as well as the central United States, railroads that will span the continent of North America and bring the Atlantic and Pacific coasts together. But your survey work is only a minor part of the job you'll be doing for us. The other part is far more grave and urgent.

"Before I discuss the precise nature of the assignment with you, however," Grant continued, leaning forward on his desk and lacing his pudgy fingers together, "I want to emphasize again that you're uniquely qualified for this post. You're not only the son of Whip Holt, a man who was a legend in our time, but you're establishing a reputation of your own that is blame near the equal of his."

Toby was embarrassed. "Hardly that, General," he protested.

"Don't be modest, young man," said Grant impatiently. "Not only has Andy Brentwood praised you to the sides, Lee Blake has written that he agrees with everything Andy says about you. Lee is an old associate of mine, whose judgment and honesty I value. The fact he's your stepfather would not sway his opinion one iota."

Toby flushed beneath his tan.

"I'm stressing your reputation, your standing in the West, so to speak, because it has a direct bearing on the assignment. The man who performs this task for us will

need the respect—and the admiration—of the Indian tribes of the area.**

Toby anticipated what was coming and waited cahnly^ while Ulysses Grant lighted a sulfur match with his thumbnail, then applied the flame to the end of the cigar stub.

Speaking through a thick cloud of smoke, the general continued, **As Andy Brentwood*s probably discussed with you, weVe received some very unsettling news from our operatives in the field and from military scouting parties. The chieftains of the Sioux, the Black-foot, and the Cheyenne have met in the Badlands of Dakota and formed an alliance. Its purpose is to drive the settlers out of the West.*'

Toby had indeed been told of the meeting of the Plains tribes. *This means a major Indian war, General," he said, "the first major war with the Indians since Andrew Jackson s time."

Grants face was blurred behind cigar smoke. "Exactly, Holt," he said. **This aUiance can mean a war in the West the likes of which has never been seen. To win such a war the United States will have to send thousands of troops out to Dakota, and even with those troops, the planning and building of the transcontinental railroad will be sorely disrupted. The immigration to the West will come to an end, and setdements, towns, and forts will be destroyed."

"But you and Colonel Brentwood think it will be possible to avoid a war?" Toby asked.

"We do. I do," Grant asserted, and jabbed a finger across his desk in the direction of the younger man. '^There's one way that it can be avoided, and that's through youl You Ve fought the Nez Perce in the Washington Territory, and you acted as a scout for the Elev-

enth Cavalry in their campaign against the Sioux. You grew up learning about the Indians from your father and visiting their villages with him, where he was always welcomed and respected. So you ve commanded their respect and have consistently proved your fairness and your friendship. They have good cause to like you, not to mention that they still revere the memory of Whip Holt.

**WeVe developed a strategy here at the War Department, which is contingent on you. This plan has won the approval of President Johnson. In essense it's very simple. You 11 be crossing the whole of the Dakota Territory while you re inspecting the railroad routes laid out by the Corps of Engineers. While you're in Dakota, it should be easy enough for you to visit every Indian community of any consequence. Talk to the chiefs and the medicine men and the other leaders. When possible, confer with the warriors themselves. These are just suggestions, mind you. You'll have a free hand to handle these towns and villages as you see fit. Convince them, if you can, that if they go through with their scheme and declare war on the United States next year, they are committing suicide."

Toby nodded thoughtfully. He knew he would be able to travel to the Indian villages without harm. Though he carried no wampum to offer the Indians as a pledge of his honorable and friendly intentions, he could speak their languages and could identify himself as the son of Whip Holt. These things would certainly stand him in good stead.

"You must convince the Indians,** Grant went on, his voice rising and hardening, "that this country will do everything in its power to protect the citizens who establish their homesteads on free American soil. We'll tolerate no

kOling, no senseless destruction and theft of property. We'll protect our people with as many troops as it is necessary to put into the field. General Blake, acting on my orders, will send units of the Eighth Cavalry to the Dakota Territory, and Colonel Brentwood in Montana will send in his units, too. And that's just the beginning. If the Indians persist with this war, we re prepared to augment the Eighth and Eleventh cavalries with two other regiments and bring our forces in the territory up to brigade strength. If that's not suflBcient, General Blake is under orders to increase the size of our units to any level he deems necessary, even if he's required to send several full divisions of troops into Dakota and to place the entire area under martial law!"

Toby could understand why Ulysses Grant had been the late President Lincoln's favorite general. He would allow nothing to stand in the way of his goals.

**We have no quarrel with the Indians," Grant continued. "It's our earnest hope that we can live side by side in peace as good neighbors. We're willing to give them large reservations of their own where they can Hve in peace; they will have ample land for farming, hunting and fishing. The choice is theirs," the general said flatly. **The Sioux, the Blackfoot, and the Cheyenne will determine whether there wiU be war or peace. We hope that you can present the alternatives to them in terms that they can grasp and that you'll be able to persuade them not to go to war against us and force us to teach them a lesson theyU never forget."

Toby took a deep breath. "All I can do is to promise you that I'll exert every effort to persuade the Plains Indians to keep the peace."

**Fair enough. Holt," the general said. "Were not asking you to perform the impossible. I'm sending imme-

diate instructions to General Blake to cooperate with you in every way that you see fit. On behalf of the people of the United States, I offer you my thanks for what you re doing."

As Toby shook the hand of Ulysses Grant, the thought occurred to him that he was being placed in a strange situation. Lee Blake was required to put his entire command, the Army of the West, at the disposal of his stepson. Well, that was fair enough. By accepting the assignment, Toby was taking on the burden of a great responsibility. War or peace in the West depended on him.

n

Major General and Mrs. Leland Blake were on hand to greet the wagon train when it arrived at Fort Vancouver. The tall, gray-haired general was very distinguished-looking in his miiform; Eulalia*s dress of soft, green wool flattered her fair skin and dark hair. As they walked the short distance from their house to the parade gi-ound where the wagon train would come to a halt, Lee noted the surreptitious glances cast at his wife by younger officers, and he chuckled quietly.

"You re amazing," he said. "You sure don t look like a woman about to become a grandmother."

She affectionately squeezed his ann but sobered quickly as she said, "All the same, I am going to be a grandmother, and I can t help worrying about Clarissa. I hope this trip wasn't too much for her."

"Im sure she's just fine," Lee replied soothingly. "You know Toby wouldn't have allowed her on the wagon train if he'd had the sHghtest doubt about her health."

When the couple reached the parade ground, they were joined by Eulalia's daughter, Cindy Holt, who had

just finished her day's schooling and still carried several books held together with a leather strap. Just as Toby Holt was the living image of his father, Whip, Cindy also bore a resemblance to her father and had the same sand-colored hair and the same clear, pale blue eyes. She was a pretty girl, having grown out of a tomboy stage. Her hair was pulled back in a ponytail, which emphasized her intelligent, animated face, and she was wearing an attractive white linen dress decorated with lace.

"I can hardly wait to see Clarissa," the sixteen-year-old girl said, "and Beth, too."

There was a moment's awkward pause, and Eulalia deliberately refrained from glancing at her husband. Both of them were conscious of the strained nature of their relations with Beth Martin and had taken pains to avoid talking about her homecoming. But Eulalia, as always, met the situation squarely. *Tm sure they'll both be equally delighted to see you, dear," she replied.

Ever since the outbreak of the Civil War, most immigrants to Portland and its environs had come to Oregon by ship after crossing the Isthmus of Panama by rail. So the arrival of the wagon train was considered a significant event, and many of Portland's citizens had crossed the Columbia River into Washington and were gathered at the parade ground.

A fast-riding scout brought word that the train had been sighted on the road that led to the fort from the north and was on schedule. The carefully planned reception began. A full regiment, eight himdred men strong, the Eighth United States Cavalry, immediately rode out to escort the wagon train to Fort Vancouver. The horsemen were followed by the post band playing the "Battie Hynm of the Republic." An infantry regiment, the Sev-

enteentb, formed a hollow square on the parade ground, while its own band played a medley of patriotic tunes, including "America" and "Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean."

At last the approaching wagon train was sighted by those in the fort, and the howitzers of an artillery unit boomed a welcome, making the horses start and shy.

Clarissa, still agile in spite of her pregnancy, was the first to jump from her wagon and break through the lines of the infantry. At her heels was Toby's shepherd dog, Mr. Blake, who, with his ears raised, trotted briskly, apparently enjoying the ceremony. Clarissa enveloped Eulalia in a hug, then hugged Lee Blake and Cindy Holt. As she presented Hank Purcell to the general, his wife, and Cindy, Beth and Rob Martin reached the group.

There was another flurry of excitement as Beth clung to her father. In the flurry of exchanged greetings, Beth managed to avoid embracing her stepmother. She barely looked at her as she nodded coolly and said, "How do you do, Eulalia?"

Certainly Eulalia had not expected to be addressed as **Mother." Beth's mother, Cathy, had been Eulalia s best friend, and she knew how close she had been to her daughter. Eulalia realized she could never take the place of the natural mother in the young woman's affections. All the same, Beth's aloofness was a dehberate slap in the face.

Clarissa, who was conscious of the slight, was embarrassed, as was Rob. But Eulalia refused to accept the snub and proceeded to handle the matter in a typically blunt, forthright manner. She reached out with both hands, caught hold of her stepdaughter s slender shoulders, and pulling her closer, planted a kiss firmly on

each cheek. **I m so glad to see you again, Beth," she said evenly.

Clarissa was pleased. Her mother-in-law, as always, could take care of herself. Rob Martin was dehghted, too, but carefully refrained from showing his pleasure. Beth would take it as a sign of disloyalty to her.

General Blake made a short speech, welcoming the wagon train's immigrants to the Pacific Northwest, and then his entire group withdrew and made the short walk to the Blakes' home. Army personnel had already been sent to attend to the wagons and horses, and they would also see that the belongings of Clarissa and Hank, Rob and Beth, were sent along to the commandant's house.

There was something of a commotion among the reunited Blakes, Martins, and Holts, each trying to talk to the other and attempting to catch up on news. Finally Lee said, **We're blocking traflBc spread out this way across the whole road. Cindy, why don t you show Hank the way?"

As they walked, Rob explained, as tactfully as possible, that he and Beth could remain only a single night. **We re going on to my folks' house tomorrow for a quick visit," he said, "and then we're going on to San Francisco. I'm wanted for my new job as fast as I can get up into the Sierra Nevada."

Lee raised an eyebrow and turned to his daughter. *What are you intending to do in San Francisco?" he asked.

Her voice was bland, her smile saccharine. "Why, I'm planning to Hve there, Daddy," she said.

Rob intervened at once. **We've decided it might be wise for Beth to live in San Francisco," he said, "so that I can be with her whenever I can snatch some time off. If she stayed here, she'd be so far away that I might not

see her for a whole year. Fd lose too much time traveling."

Everyone appeared to accept the reason, but Eulalia knew better. When Toby had surveyed a route for the railroad in the mountains of Washington, he frequently had found—or had made—the time to return home for visits to his family. The truth was that Beth was avoiding living under the same roof with her stepmother. For the present, however, EulaUa decided not to make an issue of the matter.

Meanwhile, Cindy, bringing up the rear with Hank PurceU trudging beside her, was uncomfortable.

The boy, falling all over himself like so many of the young males she knew at school, was staring at her steadily, unblinldngly, and his scrutiny made her nervous. *'Is there a smudge of dirt on my faceF' she demanded in exasperation. "Is my dress torn, or is there a hole in it?"

Hank remained blissfully unaware of the reasons for her irritation. **No, ma'am," he said. "Leastwise, I haven't seen any of those things."

The girl became even more annoyed. "Then I wish you d stop gaping at mel You act as though you've never seen a girl before!"

Hank pushed his big-crowned, broad-brimmed hat to the back of his head and, reaching under it, scratched his scalp. "Blamed if I thought of it that way," he said, **but you're right. I haven't ever seen a lady of your age before, much less met one." He swallowed hard. **If you don't mind my asking, how old are you?"

Cindy thought he was having fun at her expense and sniffed disdainfully. *Tm sixteen."

Hank looked amazed. "I could have sworn that you were close to Clarissa's age."

The assumption that she was an adult mollified the girl somewhat. Then her curiosity got the better of her. **You were just teasing me, weren t you, when you said you ve never met any girls?^

Hank shook his head vehemently and swallowed hard. "No, ma'am/* he said. **Svire as mares have colts, you re the first one I ever set eyes on!**

She found it impossible to believe him. "How could that be?**

**Pa and me,** he said, "had us a Httle spread on the Montana frontier. We didn't have any neighbors, and we were too busy raising cattle and hunting to socialize much.**

Cindy shook her head. "But surely, at school—"

"I never went to school,** Hank interjected. "Pa taught me blame near all I know about reading and writing and doing numbers, and after I moved to Fort Shaw, Clarissa and Beth started pestering me with an education.**

Cindy concluded that he was an oafish simpleton.

The boy continued to gaze at her steadily. **You*re Whip Holfs daughter,** he said at last

Cindy nodded, unwilling to listen to a long-winded, hero-worshipping recital about her father.

"You look like Toby,** Hank said.

The girl nodded her head. "We take after our papa,** she repUed.

"Toby,** Hank announced, "is ri^t handy with firearms. I guess he inherited his talent from his pa, just like I inherited mine from my pa.*'

Cindy, detecting a hint of bragging in his voice, couldn't resist replying, "As I just told you, I have some of my father in me, too. I'm a pretty fair shot myself."

Hank looked at her in openmouthed amazement. "You?*' he asked. "You re just a girll"

Her face flushed with anger. "I may be *just a girl/ but ril outshoot you any day of the weekl With any firearms you care to use!"

The boy became uncomfortable. He had actually killed a man—his father's murderer—and his skill with a gun was superior. "You shouldn't go challenging me," he told her. "I'm nearly as good a shot as Toby is."

"So am I," Cindy replied spiritedly. "Are you going to have a contest with me, or are you too big a coward?"

Hank drew himself up to his full height and towered above her. "You just talked yourself into a contest, ma'am," he said, "and you're going to be sorry. Come to think of it, let's make this a competition where you'll be double aforry. We'll make it both rifle and pistol shooting."

"That suits me just fine," Cindy replied tartly, and swept past him into the Blake house.

Beth had claimed a headache, and Rob had gone with her to their room; the others were gathered in the living room. Cindy hurried into the room ahead of Hank, anxious to tell them about the contest

Clarissa and Eulalia were deep in conversation with Lee, talking about the assignment that Toby had gone to Washington City to receive from General Grant. What they were eager to learn—and what even Lee didn't know yet—was what role Toby was going to be asked to play in the problems in Dakota. They were still pondering this as Cindy told about the contest. Indeed, the women were so immersed in thought that they failed to hear the tone of belligerence in Cindy's voice, and Clarissa smiled benignly.

"I'm glad you two are getting acquainted," she said.

''Your mother tells me, Cindy, that youTl be glad to show Hank around school and teach him what*s what."

Cindy looked reproachfully at her mother. "No, Mamal" she cried. "I'd be mortified half to death to have this dumb galoot of a boy tagging around school after me. What would my friends say?"

EulaHa was sweet-tempered but firm. "Your friends," she said, "will be very pleased to meet Hank. You will indeed take him under your wing and show him around the school.**

Cindy knew there was no appeal from her mothers decision, so she heaved a long, deep sigh.

It was Hank's turn to glower as he looked at Clarissa. **It's bad enough that you re sending me to school!" he said. "Do I have to go with girls?*'

Clarissa was unyielding. ^Tou're very fortunate, Hank. Since you'll be living here in the commandant's house, you qualify for admission to the Fort Vancouver school, and that's where you're going, beginning first thing tomorrow morning."

Lee Blake knew the boy needed to be convinced about the benefits to be derived from an education, but he realized that this was not an appropriate moment. Both of the adolescents needed to let off steam, so he intervened smoothly. "If you're interested in holding that shooting contest right now," he said, "the oflBcers' practice range isn't occupied, and I can arrange to have you use it."

**The sooner the better," Cindy snapped.

Hank was awed by the tall, gray-haired man who

wore the two stars of a major general on each shoulder.

"I'm ready right now, sir," he said, "if you'll give me a

few minutes to go fetch my rifle and my six-shooter."

**That won't be necessary," Lee told him. "We have

plenty of weapons at the range. In fact, to ensure fairness in a contest of this sort, both of you should use weapons that are unfamiliar to you."

"Let me just run upstairs to change into an old skirt," Cindy called, and she was gone in an instant.

Cindy and Hank avoided each other as they walked across the grounds of Fort Vancouver to the shooting range. However, the girl was conscious that the boy continued to study her, a puzzled expression on his face.

When they arrived at the range, Lee asked the young lieutenant in charge to provide them with identical weapons, two of the six-shooter pistols that had proved their worth so emphatically during the Civil War and two old-fashioned, single-shot rifles. While the lieutenant was fetching the weapons and ammunition, a master sergeant set up the targets a hundred feet away. The life-sized representations of Sioux warriors had been painted by this same sergeant, who was a veteran Indian fighter.

**Rifles or pistols?*' Lee asked. "Which do you want to shoot first?**

"Lady*s choice,** Hank replied laconically.

The three adults sensed the change ia the boy's mood. Once the firearms had appeared, he became quietly purposeful, businesslike, and absorbed.

'•We'll start v^dth pistols,** Cindy said.

**Colt six-shooters,** Hank said, "have the kick of an Arapaho mule, and they*re likely to fly out of a girFs hand. I wouldn*t mind if my opponent wanted to substitute a lighter weapon, say, a twenty-two caUber pistol."

"1*11 use exactly the same kind of gun he uses,*' Cindy said stubbornly.

Lee placed the two six-shooters and a box of cartridges on a wooden table that separated one shooting lane from the next. "Help yourselves," he said.

Cindy took infinite care as she loaded her pistol, inserting the shells into the empty chambers meticulously, one at a time. Hank, however, tested the gun before loading it, holding it up, squinting down the barrel, and pulling the trigger several times to test its resistance. Then he filled all six chambers in virtually a single, continuous motion.

"You may fire when ready,** General Blake said.

Cindy promptly raised her pistol to eye level, looked down the barrel at the figure of the Sioux brave, and squeezed the trigger, noting that her bullet had landed in the brave's shoulder. She nodded in satisfaction and fired a second time, again pausing to see where the bullet had gone and to judge her next shot accordingly.

Hank stood very still watching her as she fired her third and fourth shots, and it was apparent that he was impressed. Then he appeared to put his opponent out of his mind. He stared hard at the target for a long moment, raised his pistol, and emptied all six chambers in such rapid succession that they sounded almost Uke a single shot. He lowered the weapon again and let it dangle at his side as Cindy completed her fifth and sixth shots.

Lee Blake motioned the party toward the targets and led the group toward Cindy's, which he examined first All six bullets had struck the target. One had landed in a leg, another in a shoulder, and a third in an arm. The remaining three would probably have been fatal; one had penetrated a cheekbone, another had cut into the figiure's chin, and the final shot had landed near the waist. "Very nice, Cindy," the general said. "You'd qualify as a marksman in any imit under my command.**

The girl flushed at the compliment.

Lee led the way to Hank Purcell's target and stopped

short, staring in astonishment, as did the lieutenant and the sergeant.

Cindy was nonplussed. All six of her opponent's shots had landed within a radius no larger than a silver dollar, all of them centered on the figure's heart

Hank appeared to take his marksmanship for granted. He accepted the congratulations of General Blake and the soldiers quietly.

They walked back to the table, where the general handed the boy and girl the cumbersome, old-fashioned rifles and opened a box of cartridges. "This," he said, as the sergeant placed fresh targets at the opposite end of the range, **is going to be more diflScult. You 11 have to reload your rifles after each shot. You 11 have exactly two minutes from the time I order you to fixe luitil you hear the cease-fire order. Dining that time, you're free to fire as many or as few shots as you like at your target. Both accuracy and the number of shots will determine your final score.**

The contestants nodded.

Not wanting to waste time after the order to fire was given. Hank raised the rifle to his shoulder, looked down the barrel, and experimentally pulled the trigger several times. Cindy pretended to be unaware of what he was doing.

"Fire at will,** General Blake said.

Cindy lost no time and methodically loaded the rifle in the manner that her late father and brother had taught her. She was painstaking, careful, and thorough. She raised the weapon to her shoulder, sighted down the barrel, and squeezed the trigger.

In the meantime. Hank reacted as though devils were pursuing him. He loaded his rifle, then raised and fired it in almost one continuous motion. Not waiting for the

smoke to clear or to examine how accurate he had been, he instantly reloaded and fired again.

When two minutes had passed and General Blake called a halt, Cindy had made a creditable showing and had fired her rifle twice. Hank, however, had fired six shots in all, averaging one every twenty seconds. When they approached the targets, with Lee Blake in the lead, they saw that Cindy had done well. One of her shots had chpped an ear of the target, and the other had landed in an arm. Either would have been enough to incapacitate an enemy.

But all six of Hank's shots were lethal: He had shot out the eyes of the target, then had made a small, tight circle in the center of the forehead.

"YouVe done well, Cindy. Tm proud of you," her stepfather said, then turned to the boy, his hand outstretched. "If you were a few years older, Td hire you as an instructor right here at the range. Do well in school, and ril personally recommend you for an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point."

Hank flushed with pleasure. He had long taken his prowess with firearms for granted, and it was almost inconceivable to him that an ojfficer with the exalted rank of a major general should praise him.

Cindy made a great effort and forced herself to extend her hand. **That was nice shooting. Hank,** she said. "You beat me fair and square."

He gripped her hand so hard that she winced. "Heck,** he said, reddening even more, "Fd kick myself from here to the Atlantic Ocean and back if I couldn't shoot better than a girl.**

The lieutenant and sergeant, who were taking in the scene, smiled; Cindy did not. She wiped her hands on her skirt as though she had touched something unclean.

As they walked back to the house, General Blake, strolling with the boy, enlarged on the theme of the need for Hank to acquire an education. "I can see now,** he said, "why Clarissa was so insistent that you come to Fort Vancouver. You have an eye and an instinct for marksmanship that are very rare. Left to your own devices, you d have found it necessary to earn a hving, and it's possible that you'd have become a gunslinger. In no time at all, you'd have fomid yourself outside the law, and you'd have wound up with yoiu* name on wanted posters in every U.S. post office in the West. But you have a far different future in store for you, beHeve me. I'm going to make certain that you study your fool head off and that you pass the West Point entrance examinations with flying colors."

**You really think I can qualify for the academy, sir? You really think I'm going to be able to go to school there?"

"You attend to yotir end of the bargain, and I'll guarantee you that you'll become a second heutenant in the service of your country."

The boy's euphoria was so great that he did not notice Cindy's reaction. She Hstened to her stepfather in stimned disbehef. Hank Purcell was an oaf, in no way qualified to become an army officer.

When they reached the house, Cindy hastily excused herself and went upstairs to her bedchamber. Her mother and sister-in-law were in the room directly across the hall, where EulaHa was helping Clarissa impack. They called to Cindy, and she reluctantly joined them.

Eulalia smiled at her teenage daughter. "Who won the shooting match?" she asked innocently.

**Hank, of course," Cindy snapped. *1 guess shooting is the stupid boy's one accompKshment."

Clarissa ignored the slur. **He is a remarkable marksman/' she said. "According to Toby, Hank's already the equal of any adult, and if he continues to practice, he'll be in a class by himself in a few years."

"How very impressive,** Eulalia said.

**Well, Tm glad he's good for something,** Cindy said furiously, '^because in my opinion he*s the most miserable excuse for a human being Fve ever seen! I'll show him around school, and I'll introduce him to everybody—because you want me to—but that's where I draw the line. I wouldn't want a single person I know to think that disgusting boy is a friend of minel" Turning on her heel, she stalked out, went into her bedroom, and slammed the door.

Eulalia smiled painfully, then shook her head. **I was sixteen so many years ago," she said, "that I honestly can't remember it being such a horrendous age.**

Clarissa giggled. "Cindy is mistaken," she said, "if she thinks she's going to walk all over Hank. He's tough—because he's had to be. I'll bet they become close friends— if they don't kill each other first."

Rob and Beth left Fort Vancouver the following day to see his parents in Portland. Dr. Martin and Tonie enjoyed the visit of the yoimg people, and the occasion was much livelier than the visit Beth had paid her father and stepmother, for she had kept to her room almost the entire time.

Then the young couple left for California by steamboat, which now made daily trips along the coast between Portland and San Francisco. Putting oflF a decision to buy a house until Rob finished his work on the railroad, they checked in at the Palace Hotel, where they

had spent their honeymoon. While Beth settled in, Rob looked up the Harrises, who said they would be glad to entertain Beth while she stayed in the city.

Rob could not even spend the night in San Francisco, for he was wanted immediately for his work on the railroad line in the Sierra Nevada. The time for leave-taking had come, and seeing that Beth was comfortably installed in a suite in the hotel, he prepared to depart. Looking at her fidgeting in a stuffed armchair, he curbed a desire to sigh. *T hope to goodness you re going to be all right,** he said.

There was a note of suspense and excitement in Beth's laugh. **Why shouldn't I be all right?" she demanded. 'There's no better or safer place in all of San Francisco than this hotel."

**! know,** Rob replied glumly, unable to shake off a strange sense of foreboding. Still reluctant to go, he said, *Tou have ample funds, and if you need more, you have only to apply to Chet Harris for them. Don t be afraid to spend money. That's why we have it.**

"I refuse to be foolish about that,** she said, *T3ut I wont argue the point.**

He didnt want to argue about anything. "1*11 admit to you," he said, **that Fm worried for you. You re young, youre very beautiful, and you*re wealthy enough to be a target of the unscrupulous. Be careful of the friendships you make and always keep in mind that the Harrises are nearby if you need real friends."

*1 wont forget,** she promised, though she really had no desire to accept invitations from the stuffy Harrises. Tired of his lecturing, she sHd her arms aroimd his neck and kissed him.

That gesture ended the discussion with finality.

Rob embraced her, then pulled himself away. Til come down from the mountains to see you whenever I can. You can bet on that," he said as he hurried toward the door.

A moment later Beth was alone. On sudden impulse she walked to the table. On it stood a half-empty bottle of champagne from which she and Rob had consumed a farewell drink. She refilled her glass, then held it aloft. "Here's to me," she said, "and to my new life as a free woman."

One of the Sioux villages was located on the edge of the Badlands; it was a small community made up of a number of tepees, a corral for horses, and little else. The inhabitants subsisted on the deer and bufiFalo that the hunters brought back from the woods and prairies; the squaws grew few vegetables because the soil here, like that of the Badlands itself, was too poor to grow good crops.

What made this village noteworthy was the chief who ruled it. Tall Stone, who was named after the odd-shaped figures that dotted the Badlands. Tall Stone was of average height, stocky, with a barrel chest, brawny arms, and thick, stubby fingers. His large stomach indicated his love of food and, when he could get it, the rum and beer of the white man.

Tall Stone was highly regarded by Thunder Cloud and the other leaders of the Sioux; he had fought with distinction in the battle in which the Sioux had confronted the Eleventh United States Cavalry. He was also an acknowledged leader in the movement to form a solid aUiance with the Blackfoot and the Cheyenne. More than this, the reputation of Tall Stone, now in early

middle age, rested on his undying hatred for all white settlers who dared to invade the lands of his people.

No one knew exactly why Tall Stone's temper was so violent and his nature was so cruel. No one dared ask him. It was rumored, however, that more than three decades earlier, when he had been a very young warrior, he had suffered excruciating embarrassment at the hands of Whip Holt. According to the story, he had accosted the great frontiersman, who had been trapping and trading in Dakota, and the Indian had been deliberately insulting. Holt had refused to duel with him, saying that he didn't believe in senseless killing, and when Tall Stone had persisted, the mountain man had uncoiled his famous whip from his waist and had thrashed the young brave. Ever since that day. Tall Stone had been the sworn enemy of everyone who claimed allegiance to the United States.

Despite Tall Stone's love of food and drink, he was still a warrior to be feared, and his threats against the white man had not been idle. In his time he had taken many scalps—of men, women, and even children—and he proudly wore a necklace of human teeth, taken, he said, from the settlers who had dared to set foot in the Dakota Territory. Even his own people were known to cringe when they saw him coming.

Now the residents of the village were astonished because he was preparing to entertain a party of white people. Ma Hastings, the cutthroat leader of a notorious bandit gang, had, like the Indians, also left the Montana Territory because of the presence of so many troops. In Montana Ma*s son and chief lieutenant, Chfford, had been killed by Toby Holt while the gang was about to raid a settler s ranch, and Ma had vowed she would not rest until Toby Holt was dead.

Now a special meeting had been arranged between Ma Hastings and Tall Stone, and several tepees had been erected for the use of the visitors. The chief obtained the services of two squaws as cooks, and he commandeered the nineteen-year-old Gentle Doe to serve his guests and himself.

Everyone in the village knew that the chieftain lusted after Gentle Doe. They also were aware that the aptly named maiden, as lovely as she was shy, wanted no part of Tall Stone, and with good reason. Since earliest childhood she had feared his temper tantrums, his cruelties, and his vicious mistreatment of anyone who crossed his wiU.

Gentle Doe's parents were no longer alive, however, and as an orphan she was not in a position to determine her own destiny. Under the unwritten laws of the Sioux, she had to accept any man whom the chief instructed her to marry. But not even Tall Stone was going to force her into marriage with him against her will. He was too proud for that, and he contented himself with the belief that she would come to him in her own good time.

Now Gentle Doe went to the pit where an outdoor cooking fire was burning and vigorously stirred the pot containing the stew the older squaws had made. In it were chunks of venison, carrots, kale, dried green peas, pickled sugar beets, and pieces of celery root.

Tall Stone stood nearby, his eyes fixed on Gentle Doe as he observed every move she made. The intensity of his gaze made her nervous, and she said the first thing that came to mind as she went to the stack of govuds that would be used to serve the stew. "How many guests will Tall Stone entertain today?*'

"Two will share with me, and you will serve us," Tall

Stone said succinctly. **The others, seven or eight warriors in all, will go and dine with the unmarried warriors. They will be served by the old squaws.**

He still scrutinized her, and Gentle Doe felt she had to say something to ease the feeling of being devoured by his eyes, **Your guests are Sioux from another villager

Tall Stone shook his head. **They are not Sioux," he said. **They have pale skins."

Despite herself, Gentle Doe stared at him in open-mouthed astonishment. Because she kept to herself as much as possible, she was one of the few people in the village who did not know Tall Stone was meeting with whites.

He realized she was shocked, and his thin lips twisted in a lopsided grin that more closely resembled a grimace. "Gentle Doe," he asked, "has heard of the woman who is called Ma Hastings?"

She shook her head.

**Her fellow paleskins are her enemies, Just as they are the enemies of Tall Stone. She is the head of a gang of robbers and bandits that preys on settlers and steals their horses and cattle. When they object, she kills them, just as I, too, slaughter them."

The young Indian woman shuddered.

"She had two sons," Tall Stone continued, "but one of tibem was killed by Toby Holt—may the gods strike him with a bolt of lightning. Now she has only one son, whose mind and will have been softened by the strong drink of the paleskins. It is said that he is useless, but this is something I will judge for myself. Ma Hastings and her son, Ralph, will be my guests at supper."

Gentle Doe wondered what Tall Stone and Ma

Hastings could have in common, but something he had said intrigued her far more. Like all Sioux, she had heard about Toby Holt and was famiUar with stories about the valor of his father. **Gentle Doe did not know that Tall Stone was the enemy of Toby Holt," she said softly.

He nodded, his jaw set, his eyes fiery. In the battle that the Sioux had fought with the Eleventh Cavalry, Tall Stone had been bested by Toby Holt, though they had not met face to face. From a place of conceahnent. Holt—and it definitely was Toby Holt, according to braves who had seen him—had shot Tall Stone's hand. The Sioux chief, fibading himself weaponless, was suddenly surrounded by soldiers, who forced him to flee from the Sioux stronghold in the Montana mountains. This defeat, linked to his earlier humiliation by Whip Holt, increased the Sioux chieftain's rage against all white men, but particularly the Holts.

**Tall Stone and Ma Hastings," he said triumphantly, "will sign an alHance in blood and will swear that they will not rest until Toby Holt breathes no more." He laughed coarsely. "Also, we will sign another pact to support each other in raids on the paleskin settlers in Dakota and Montana."