AFTER THE GUNS FELL SILENT

“We did not do the best we would, but the best we could.”

—WILLIAM H. TAYLOR, CONFEDERATE SURGEON

By June 1865, the last of the Rebel armies had surrendered. The U.S. Army captured the Confederacy’s president, Jefferson Davis. The rebellion was over, and the union of the United States had been preserved. Slaves were free. Soldiers and sailors returned to their families.

THE POWS

Among the men who went home were prisoners of war. Several hundred thousand soldiers spent months and even years as captives. After the war ended and the prisoners were released, the public saw the full horror of the camps. Men emerged emaciated and deathly ill. Both Northerners and Southerners shouted accusations of mistreatment. The charges were impossible to deny.

Two large prisons camps, built in 1864, were particularly notorious. At Andersonville, Georgia, 45,000 Union troops suffered in stifling heat and wet cold. About 13,000 of them died.

In September 1864, Confederate Surgeon General Moore sent Dr. Joseph Jones to inspect the prison. The southern physician reported that conditions were atrocious. Union prisoners suffered from scurvy, diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, and hospital gangrene. “Millions of flies swarmed over everything and covered the faces of the sleeping patients,” Jones wrote, “and crawled down their open mouths and deposited their maggots in the gangrenous wounds of the living and in the mouths of the dead.”

The infamous Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. This photograph from August 1864 shows the tents of blankets and sticks constructed by the prisoners. The wooden structure in the middle of the photograph is the latrine. Streams of water flow in and out of the toilet area, creating conditions that spread intestinal diseases. After the war, the prison’s superintendent, Captain Henry Wirz, was convicted in a United States military trial of the deaths of thousands of prisoners. In November 1865, he was hanged.

At the Union prison camp in Elmira, New York, about 12,000 Confederate prisoners endured the brutal, icy winter of 1864–65. A soldier’s only protection from snow and below-zero temperatures was a makeshift wooden barrack or tent, neither adequately heated. The conditions were hard on Southerners not used to snow and frigid weather. Nearly 3,000 died, earning the prison the name Hellmira.

The Union prison in Elmira, New York, called Hellmira by the Rebels. Groups of Confederate prisoners line up for roll call among the tents in which they lived. Poor sanitation, overcrowding, and a frigid winter led to the deaths of about a quarter of the prisoners.

Confederate hospital matron Kate Cumming was bitter about their treatment. “We starved their prisoners!” she later wrote. “But who laid waste our corn and wheat fields? And did not we all starve? Have the southern men who were in northern prisons no tales to tell—of being frozen in their beds, and seeing their comrades freeze to death for want of proper clothing?”

Phoebe Pember, a Confederate matron at Richmond’s Chimborazo Hospital, admitted that the Union soldiers held by the South were in terrible physical condition. Still, she blamed the Union army for its abuse of Rebel captives. “The Federal prisoners we had released were in many instances in a like state,” she wrote in her memoirs, “but our ports had been blockaded, our harvest burned, our cattle stolen, our country wasted. Even had we felt the desire to succor, where could the wherewithal have been found?” She believed the U.S. Army “could have fed his prisoners upon milk and honey, and not have missed either.”

Prisoners of war on both sides were fed poorly and suffered from malnutrition. Scurvy was common. With weakened bodies, the men became susceptible to other diseases. They developed respiratory infections such as colds, bronchitis, and pneumonia. Their ailments worsened with exposure to harsh weather.

Charles Lapham, from Vermont, was twenty-three when a cannonball hit his legs during an 1863 Maryland battle. Two days later, a surgeon amputated both. After about a year, Lapham received two artificial legs that worked so well that he could climb stairs. He went on to work in the U.S. Treasury Department for more than twenty years, until his death at age fifty-one.

Contagious illnesses, such as smallpox, spread in the crowded prison conditions. Sanitation was usually poor. Human waste was dumped into drinking water sources, infecting soldiers with typhoid fever, dysentery, and diarrhea. Neither army had enough doctors to treat all its prisoners.

At least 55,000 men died in military prisons. Many of the survivors never fully recovered their health after the ordeal.

INCOMPLETE BODIES

Although the fighting had ended, the war’s damage was far from over for the wounded. Historians estimate that at least 45,000 survivors were amputees. Before the war, most of the men had used their bodies to make a living—as farmers, construction workers, manual laborers. Without an arm or leg, they could no longer perform those jobs.

While the war was still raging, inventors created more than a hundred different designs for artificial limbs. Depending on the model, the prostheses were made of cork, wood, leather, rubber, metal, and cloth. The U.S. government paid for part of the cost of an amputee’s artificial limb. But the benefit was strictly for Union soldiers, not Confederate veterans. Southern state governments and private charities helped Rebel amputees buy prostheses.

Jackson Broshears enlisted in an Indiana infantry regiment when he was eighteen. In December 1863, he was captured by the enemy in Tennessee. The Confederates moved Broshears to the Belle Isle prison camp near Richmond. By the time he was released in a prisoner exchange after three months captivity, Broshear had lost nearly eighty pounds. This photograph was taken at a Union hospital in May 1864, after he had been under medical treatment for two months. The doctor’s notation at the time said that the young man was improving, but Broshears never regained his health. Back home in Indiana, the twenty-year-old died that October. Prisoner photographs like this one stunned and outraged Northerners.

Many men learned to use their prosthetic limbs while recovering in the hospital. Special hospitals in the North taught wounded veterans new skills such as bookkeeping, telegraphing, and shoemaking. These jobs didn’t require strenuous physical labor or full use of arms or legs.

With or without a prosthesis, though, many veterans were ashamed to be missing a limb.

In a June 1861 battle, Virginian James Hanger, age eighteen, was struck by a cannonball just two days after he enlisted. Hanger was captured, and a Union surgeon amputated his mangled leg.

After being released in a prisoner exchange two months later, Hanger went home to recover. He had been an engineering student before the war, and he decided to craft an artificial wooden leg for himself. The Hanger Limb worked so well that the young man convinced the Confederate government to buy it for other amputees. That was the beginning of the J. E. Hanger company, which still produces prosthetics today.

In this photograph from around 1902, an amputee wears an artificial leg made by the Hanger company.

Besides the amputees, tens of thousands of men—North and South—were left with some kind of disability. These included hearing loss from thundering artillery guns; joint damage from carrying heavy loads; and partial blindness from an eye injury. One soldier in a U.S. Colored Troops regiment tripped on a tree branch during a battle charge, and the other men unintentionally trampled him. His back was permanently damaged.

Many amputees used crutches and wheelchairs to get around. In some cases, men found prostheses uncomfortable. Others were unable to find a good fit. This soldier from Pennsylvania lost both his legs to amputation after an 1864 battle injury in Georgia.

Union soldiers were eligible for government financial support. The amount they received depended on the extent of their disability and their military rank. Widows and orphans of dead soldiers could also get a pension. The system changed during the decades after the war, and starting in 1892, female Union nurses received pensions, too.

Confederate soldiers weren’t eligible for these federal benefits. Each southern state eventually offered pensions to its veterans.

SOLDIER’S HEART

War wounds weren’t always as visible as a missing leg. The excitement and glory that soldiers expected to find in battle turned out to be terror and pain. They’d seen bullets and cannon shells tear human bodies apart. They’d watched friends suffer agonizing death from disease.

Long after they returned home, many men continued to be cursed with frightening memories and hallucinations of danger. In a physical reaction to these thoughts, their heart raced. Some abused alcohol or became violent. Their families noticed odd behavior and changes in personality.

At the time, this was called battle sickness, or soldier’s heart. Today it is known as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the 1800s, mental illnesses were not understood or treated the way they are now. Affected men sometimes committed suicide or ended up in mental hospitals suffering from severe depression. Based on medical records of veterans seeking pensions, historians believe that these after-effects lasted longer and were more severe in soldiers who served as teens.

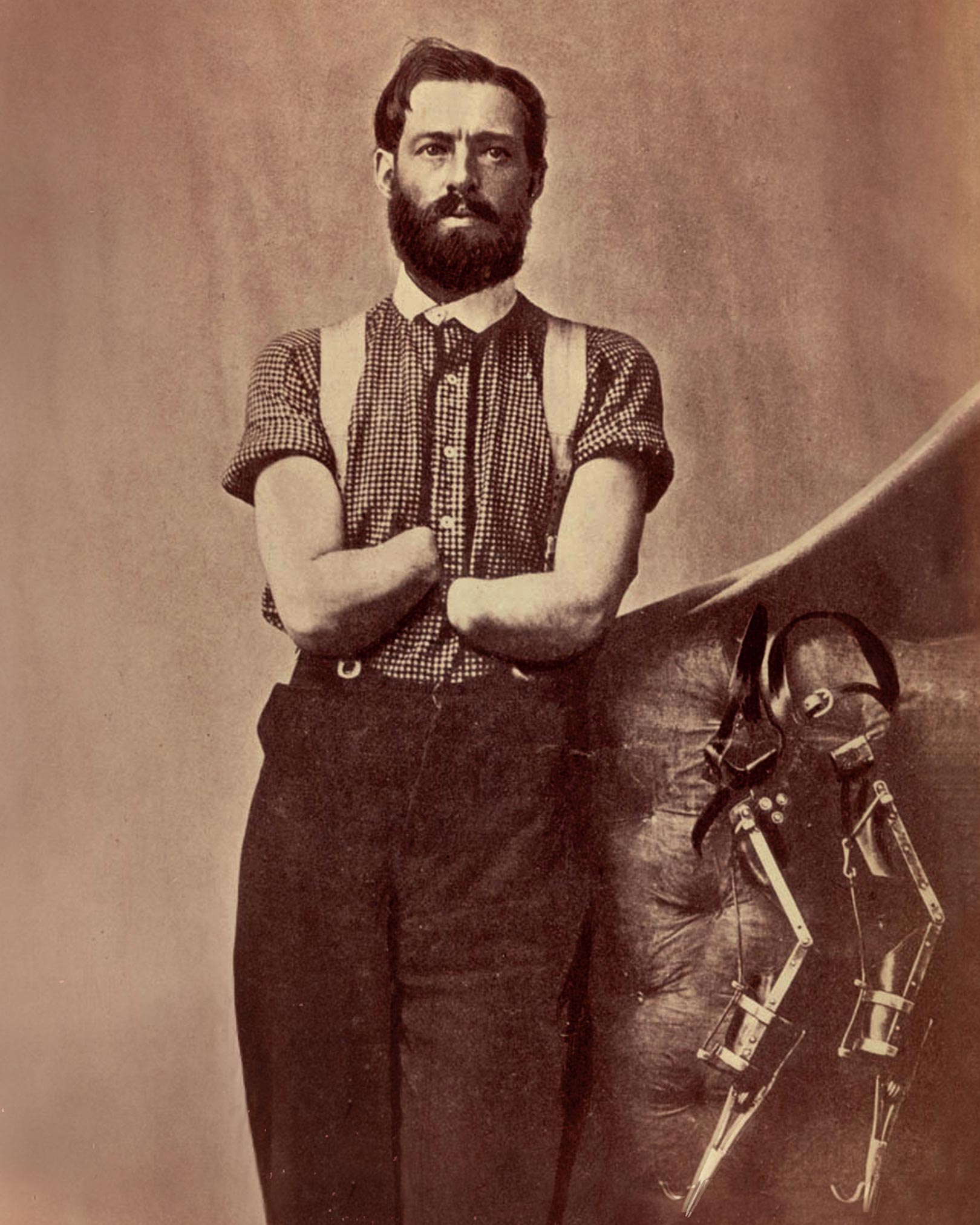

Samuel Decker, from Ohio, lost his forearms when his cannon fired too soon during an October 1862 battle in Kentucky. He invented his own artificial arms that he used to write, dress, eat, pick up small items, and carry packages. Decker served as doorkeeper at the U.S. House of Representatives. This photograph was taken in 1867 when he visited the Army Medical Museum.

The conflict took a toll on the doctors, too. Union surgeon James Benton, from New York, wrote in a letter twenty years after fighting ended, “The war and three years of service have made me a physical wreck.”

A SILVER LINING

The Civil War was a dreadful period of blood and germs. Because of the great number of casualties—unprecedented in American history—the medical community was forced to respond with improvisation, innovation, and education. From those terrible four years came changes that enhanced future medical care in the United States.

Physicians

Thousands of doctors went home with a deeper understanding of the human body and with more experience in diagnosing illnesses. They learned better ways to care for the sick and wounded. After performing countless operations, the surgeons developed skills which significantly improved by the war’s end. Most of the surgeries were performed under anesthesia, demonstrating that chloroform and ether were effective and safe.

One Confederate physician wrote, “I have lost much, but I have gained much, especially as a medical man. I return home a better surgeon, a better doctor.”

The American approach to medicine became more scientific. Encouraged by the army medical departments, doctors kept records of their treatments and surgical techniques. Then they shared what they’d learned with colleagues in order to improve recovery and survival rates. The sharing of knowledge continued after the war as new medical journals were published throughout the country.

In 1862, Union army Surgeon General William Hammond established the Army Medical Museum to collect specimens from surgeons, including bones from amputated limbs. The collection also contained photographs of injured soldiers, complete with information on their wounds and surgeries. The materials were intended as a resource for doctors who wanted to learn more about injuries, disease, and treatment. Starting in 1870, the war records were gathered together into the multivolume Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, which became a valuable reference for physicians.

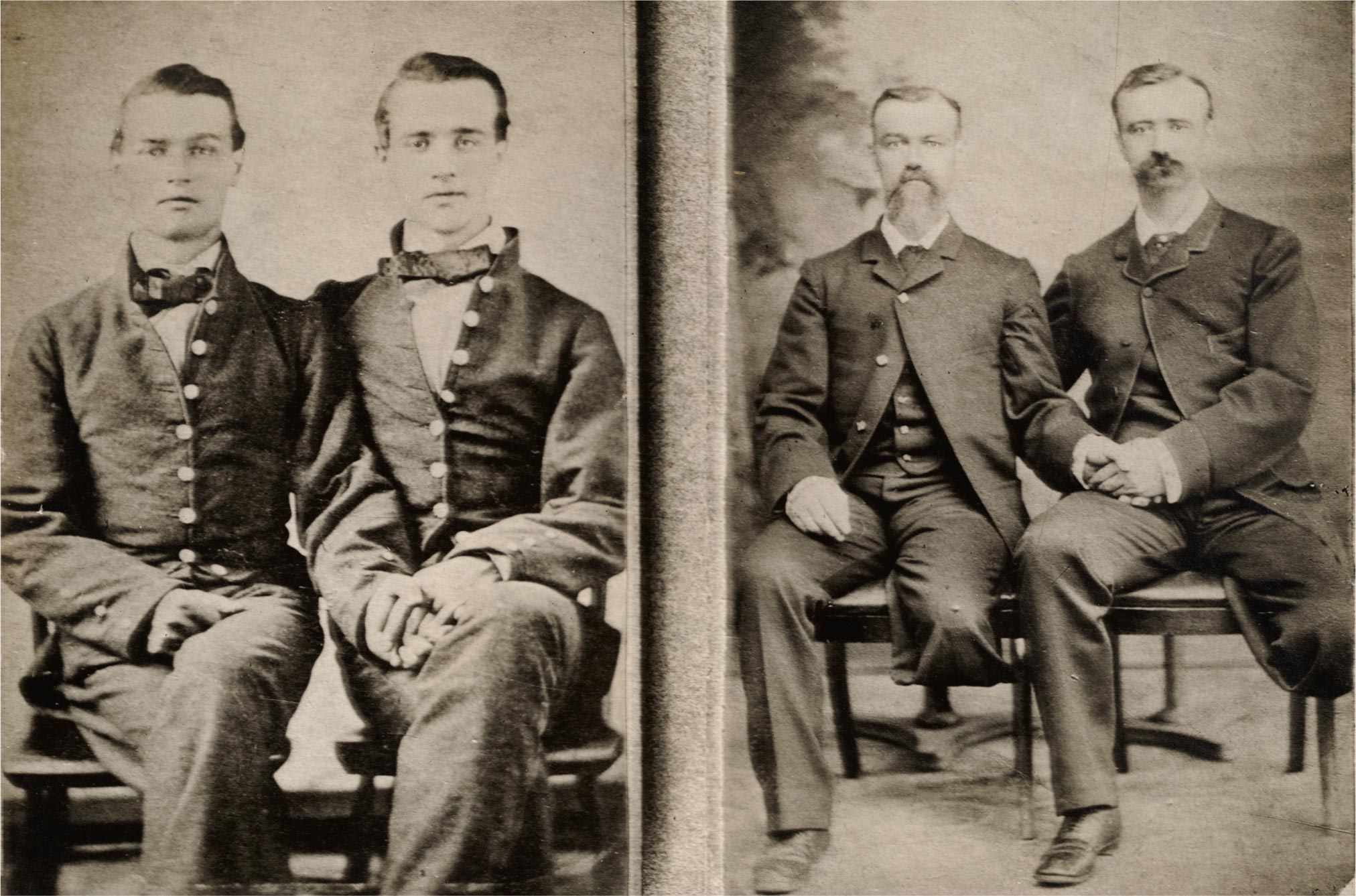

The Walker brothers of North Carolina enlisted together on the day their state seceded, May 20, 1861, around the time of this photograph. Levi (left) was nineteen, and Henry was twenty-four. Before the war began, they had worked alongside their father at a wool factory.

In July 1863, the Walkers were among more than 160,000 soldiers who fought at Gettysburg. On the battle’s first day, Levi was shot while carrying his regiment’s flag. A Confederate surgeon amputated his left leg the next day at a field hospital. When the southern army retreated two days later, Levi had to be left behind with about 7,000 other Confederate wounded. The Union army took him prisoner and held him for four months until his release in a prisoner exchange.

Henry, an officer, joined the rest of their regiment in the Confederate retreat from Gettysburg. About two weeks after his brother’s injury, Henry was shot in the left leg in fighting at Hagerstown, Maryland. Just like his younger brother, he underwent an amputation. Henry, too, was taken prisoner, but he wasn’t released for ten months.

Both brothers returned to North Carolina, married, and had children. Levi was a businessman, and Henry became a doctor. In 1887, the Walkers re-created the first photograph—without their left legs. They lived exceptionally long lives, with Levi dying at ninety-three and Henry at ninety-two.

Managing Casualties

Medical director Jonathan Letterman instituted a procedure to separate the wounded into three groups. That ensured that those who would most benefit from care received it first. This triage approach set the stage for our modern emergency response systems, both civilian and military.

An efficient system evolved to move the wounded from battlefield to hospital. Trained ambulance workers saved lives by speedily transporting the injured to doctors, just as emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics do today. New ambulance designs made the ride less jarring and painful to a wounded soldier.

Hospitals

Because so many ill and injured men had healed in military hospitals, public attitudes changed. Instead of considering a hospital as a place to die, Americans realized that it could be a place to recover. Hospitals assumed an important role in the nation’s medical care. Doctors who had treated thousands of patients during the war managed these hospitals and served on the staffs.

Although no one yet understood that microbes caused diseases, the medical community had learned that lives were saved when hospital staffs used disinfectants and followed hygienic practices. Doctors observed that by isolating patients with contagious illnesses, such as smallpox and hospital gangrene, they could prevent epidemics.

Nursing

Women showed their value in healing the soldiers. Physicians recognized that hospitals were successful when they followed the same methods of care used by women for their families. Clean bodies, clothes, and bed linens. Nutritious food. Compassionate, personal attention. For the first time in the United States, nursing became a profession that women could pursue. In the years following the war, American schools devoted to nursing were founded.

Support For Veterans

Aid organizations were established early in the war to support the fighting men. When the war ended, these groups continued their mission. The U.S. Sanitary Commission helped soldiers receive back pay and pensions, showing them how to submit the correct forms to the appropriate government office. Relief groups assisted veterans in paying medical bills. They honored the soldiers’ service by erecting monuments and maintaining cemeteries.

Union soldiers who lost limbs stand outside the office of the U.S. Christian Commission in Washington. Relief groups provided aid to soldiers whose injuries made it impossible to work.

This granite monument, crowned with a bald eagle, stands in a Burlington, Vermont, park. The state’s chapter of the Woman’s Relief Corps raised money to erect the monument in memory of Civil War soldiers and sailors, dedicating it on Memorial Day 1907.

Currier & Ives published this print in 1865. In memory of a loved one, people filled in the name of the dead soldier, his regiment, and where and when he died. Families often framed these memorials.

The blood and germs of the Civil War changed the lives of countless Americans. For many, the medical knowledge and experience gained during those four years offered hope for a healthier future. But for others, the legacy of the war was agony and loss. Even after the physical wounds healed, veterans and families couldn’t escape the painful memories.

To honor those who died, some communities designated a day each spring when friends and loved ones gathered in tribute to the fallen. People placed flags and flowers on the graves, paraded through town, prayed, and gave speeches. This tradition spread across the country during the late nineteenth century, and it later expanded to honor Americans who died in subsequent wars. Today, Memorial Day is an official national holiday at the end of May.

Civil War remembrance events included the singing of old war songs. One of the most popular, “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground,” expressed the sorrow that lingered for decades after the devastating conflict ended.

We are tired of war on the old camp ground,

Many are dead and gone,

Of the brave and true who’ve left their homes;

Others been wounded long.

We’ve been fighting today on the old camp ground,

Many are lying near;

Some are dead and some are dying,

Many are in tears.

(chorus)

Many are the hearts that are weary tonight,

Wishing for the war to cease;

Many are the hearts that are looking for the right,

To see the dawn of peace.

Tenting tonight, tenting tonight,

Tenting on the old camp ground.