IT DID NOT TAKE LONG for Bellamy to establish the Sultana as one of the most feared of pirate vessels. On December 16, 1716, just a day after taking command of his new flagship, he and LeBous, with Williams and the Marianne also operating in the vicinity, captured a merchant ship out of Bristol, England, called the St. Michael. They held the ship’s crew on the nearby island of St. Maarten while they plundered its cargo. They then returned the ship to its captain, but not before thirteen of his crew voluntarily joined the men of the Sultana. A fourteenth member of the St. Michael’s crew also became part of Bellamy’s pirate band, but his participation was anything but voluntary.

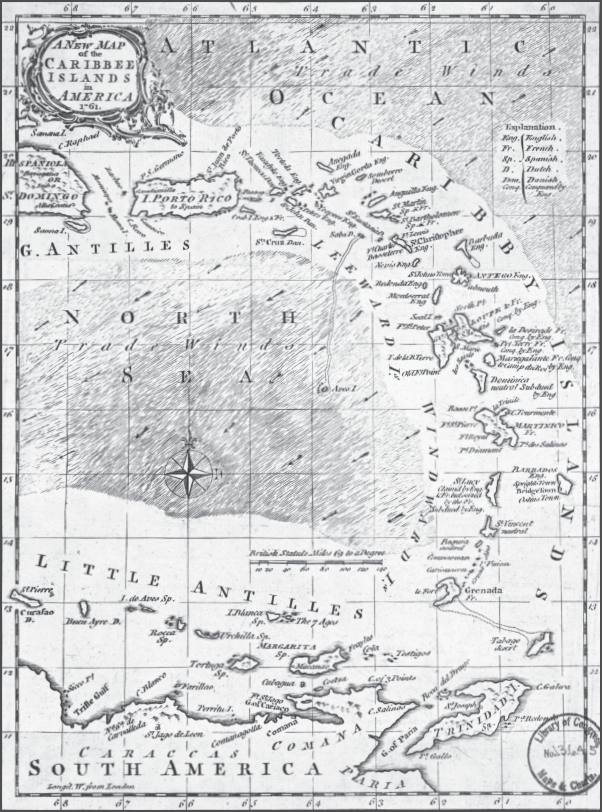

This map shows the Caribbean at the time known as the golden age of piracy. Because of its location between the southern tip of North America and the northern part of South America, the Caribbean contained major trade routes for merchant ships, making it prime hunting grounds for pirate ships constantly on the prowl.

His name was Thomas Davis. Having first gone to sea when he was seventeen, he was now the St. Michael’s shipwright, or onboard carpenter. The last thing Davis wanted was to be a pirate, but the Sultana badly needed his skills. As Bellamy ordered Davis aboard the Sultana, the young man begged him to let him go. The St. Michael’s captain also pleaded for Davis’s release. Finally, even though he had promised the carpenter that he would eventually be set free, Bellamy called a meeting of the pirates and let them decide Davis’s fate. The crew, offended by the fact that he had so vehemently opposed becoming a pirate, forced Davis to do just that.

The St. Michael would rank as one of the largest vessels Bellamy plundered after he took command of the Sultana. It was the first ship he took using a strategy that would become known throughout the seafaring world. As soon as they spotted prey, Williams, in the fast, highly maneuverable Marianne, would chase after it and track it down. Just as the targeted ship was preparing to put up a fight, Bellamy would show up in the much larger Sultana, its cannons pointing ominously at the prize vessel. On almost every occasion, the result would be an immediate surrender.

As Bellamy became increasingly successful and well known, LeBous grew tired of operating in the younger pirate’s shadow. By mutual agreement, they parted ways, and LeBous sailed off to seek glory of his own. Bellamy, on the other hand, now had a different desire. The Sultana’s hold was filled almost to capacity with barrels and crates containing clothing, cloth, foodstuffs, and other valuable plundered goods. Special compartments that had been built in the space between the deck and the hold housed bags of coins, gold dust, and jewelry. The exact value of the stolen treasure on the Sultana was not recorded, but there is no question that it was worth a significant fortune. Yet Bellamy was not satisfied. He wanted an even bigger, faster ship, one that could carry even more booty, one that could outrun even the British navy’s fastest ships.

Then, in late February 1717, the Sultana’s lookout spotted the Whydah making its way back to England. As Bellamy gazed out at the huge slave ship, he realized he was looking at his heart’s desire. Like some other pirate captains, Bellamy craved having a slave vessel for his flagship. Slave ships were built for speed so that they could complete the Middle Passage as quickly as possible, and they were also larger than most other vessels. Speed and size were important assets to pirate ships for pursuing prey and for storing large amounts of plunder. And slave ships had two other valuable features as well: they were always heavily armed, and they had huge kitchens called galleys, with large cooking pots and other utensils that could be used to feed more than a hundred men.

Now, as Williams trailed behind him in the Marianne, Bellamy stepped up his pursuit in a race that under ordinary circumstances the far swifter Whydah would have easily won. Bellamy could not have known it, but his chase was aided by an extraordinarily valuable cargo whose equally extraordinary weight slowed his target.

Still, it took Bellamy’s vessel three full days of sailing as fast as it could through the waters between Cuba and Hispaniola, known as the Windward Passage, to catch up with Captain Prince’s expertly piloted ship. Finally, the Sultana pulled within cannon range of the slave vessel off Long Island, in the Bahamas. Bellamy had already ordered that his personal pirate flag be raised. Now he had his gunners fire two shots across the Whydah’s bow. The experienced Captain Prince, fully aware that to put up a fight he had no chance of winning meant incurring brutal treatment at the hands of the pirates, lowered both the Whydah’s flag and its sails, indicating his official surrender.

Once Prince gave in, Bellamy ordered that he anchor the Whydah off Long Island and, within hours, began the task of transferring his huge cargo of booty from the Sultana to the Whydah. The transfer took several days and was a remarkable sight: there, in a remote area of the vast Caribbean, small boats continually traveled back and forth between the two ships, accompanied by shouts from Bellamy and his officers directing where on the Whydah the crew members should place the Sultana’s cargo.

Bellamy and his men always looked forward to discovering what was included in the loot they had just captured. But when they looked in the Whydah’s hold and between its decks, they received the greatest and happiest surprise of their lives.

In the Whydah’s hold, the pirates found hundreds of elephant tusks stacked like cordwood, representing a fortune in ivory alone. Slabs of cinchona, bark used for making quinine, a medicine for curing malaria, were also worth an enormous amount of money. Huge sacks and barrels of valuable sugar, molasses, and indigo plants for making dye filled the rest of the hold.

And between the Whydah’s decks were sacks and sacks of precious gold and silver. Also hidden were rare pieces of African jewelry and bags of gold dust. Most spectacular of all was a magnificent box of East Indian jewels, whose contents, according to one of the pirates, included a ruby the size of a hen’s egg. As Peter Cornelius Hoof, a longtime Bellamy crew member, testified, “The Money taken in the [Whydah], which was reported to Amount to 20000 or 30000 Pounds, was counted over in the cabin, and put up in bags, Fifty Pounds to every Man’s share, there being 180 Men on Board.” When distributed, that was enough money to last most pirates a lifetime.

When all of the booty had been transferred, Bellamy, as was his custom, gave Captain Prince’s crew the option of joining the pirates. A dozen men accepted the offer. At the same time, the young reluctant carpenter Thomas Davis reminded Bellamy that he had been promised eventual release. But once again the crew outvoted their captain’s proposal to release the carpenter, with one pirate exclaiming that they “would first shoot him or whip him to Death at the Mast” before letting him leave.

The only question remaining was what to do with Captain Prince and the loyal members of his crew. Bellamy was grateful to Prince for surrendering so peacefully, keeping the Whydah and its extraordinary cargo from jeopardy. Black Sam was overjoyed to have acquired his ideal flagship and a booty far beyond anything he had ever imagined. So it was no surprise that he gave Prince the Sultana and told him that he and his crew were free to go.

They were no sooner out of sight than Bellamy began making physical changes to the Whydah. First, he had his crew remove the long platform on top of the pilot’s cabin upon which many slaves had made the horrific journey from Africa to the Caribbean. Then, in order to make the Whydah even faster, they took down the forecastle, a structure in the ship’s bow, where some of the slave ship’s crew had been quartered. It was tall and bulky and its weight reduced the maximum speed the Whydah could attain. So, too, did the pilot’s cabin and the quarterdeck, a raised deck behind the mainmast, both of which were also removed. Bellamy also had his men strip off the lead sheathing that covered the ship’s hull and was designed to protect the vessel in the event of a collision with another ship. Bellamy hated to see it go, but he knew the Whydah was quicker and more maneuverable without it, and he felt it was a sacrifice he needed to make.

In addition, ten cannons were added to the ship, giving it twenty-eight large guns in all, an amazing number for a nonmilitary vessel. The Whydah’s dramatic transformation from a slave ship to one of the most formidable and speedy pirate vessels in history was complete.