In the midst of the gloomy picture of state education that I painted in this book, there are some little stars of hope. This is the story of two of them.

Grace Patterson came to realise that her son Miles was getting into ‘the wrong crowd’ at Westminster City School, a state school not very far from the Houses of Parliament in central London. She also knew he was not learning very much. But she did not know the full story.

Miles was about thirteen and big for his age. He was taking advantage of his size to threaten younger boys, aged eleven or so, demanding that they give him the lunch vouchers many had because they came from relatively poor families. When he had extorted about five of these vouchers, he would sell them to other boys. Then, after school, he would spend the profits in an amusement arcade.

Away from school, Miles had been involved in an incident with a knife. He had started shoplifting, too. As for academic work, he wasn’t interested. He was unable to do long division or multiplication. His life was heading towards academic failure and crime.

The crunch came when Grace was called in by the school because Miles had been in trouble with the police. A £10 note had been stolen by a friend of his and Miles had looked after it for a while.

So what did Grace do?

Grace Patterson made great sacrifices for her sons’ education because she wasn’t content with what the state provided.

She could easily have blamed other people or the school or the world we live in. Instead she took upon herself the responsibility of putting her son’s life on a better track.

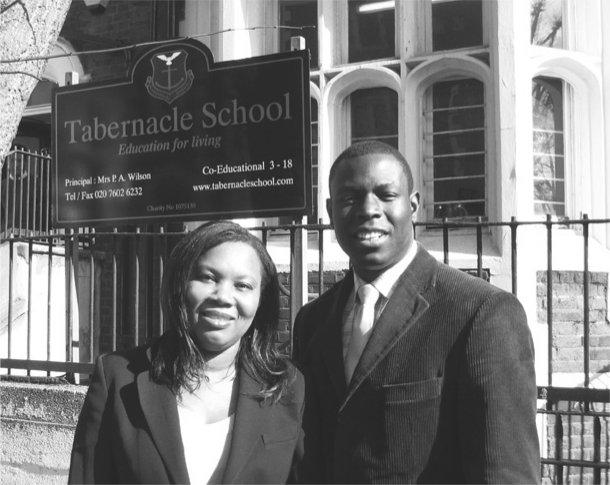

Grace knew of the Tabernacle School because she already worshipped at the church which had created it. But sending Miles to the Tabernacle was not an easy option. She was a single mother on a low income, living on a council estate in south London. The Tabernacle is in Notting Hill, west London. She had to send Miles across the city each day to go to it. Far harder, by sending her son to the Tabernacle she was giving up free education provided by the state and instead devoting a high proportion of her income to school fees. The Tabernacle’s fees are small compared to those of big, well-established private schools such as Eton or Cheltenham Ladies’ College. But they were massive for her.

After Grace made the move, it cost her £500 per month (in all twelve months of the year) for Miles and her younger son Michael to attend the school. This was out of her net income of £1,450 a month. So she was giving up more than a third of her taxed income for schooling. As if that was not enough, she also paid a tithe – 10 per cent of her income – to the Tabernacle church. ‘It was very difficult. I worked a full-time job and then also had a job at the weekend for three or four years.’ She went without a foreign holiday for longer than that. New clothes were a rarity.

So what did her sacrifice achieve? Was it all worthwhile?

Miles Nanton was transformed from a troublemaker to a role model.

Well, six years on, I talked to Miles. He frankly admitted to me that if he had stayed at his state school, then by the time I met him he would have been in prison and would have fathered several children outside marriage. In other words, his life would have gone badly wrong and other people would have suffered, too.

And how is his life turning out after going to the Tabernacle School instead? He has become a particularly civilised and responsible young citizen – a gentle giant. His friend and classmate Kiaran told me that Miles was a role model on his council estate, to the point where other children came to him for advice. It was easy to believe. The pair of them are ambitious: they have made a short film together which was premiered at a cinema in Shaftesbury Avenue. Miles is currently trying to get into film school. Meanwhile he is teaching part time at the Tabernacle.

How did the school succeed in turning round Miles’s life? The answer is complex and difficult to define. Part of it is undoubtedly the dedication of Pastor Derrick Wilson, who founded the school, and his wife Paulette, the principal. Part of it is the very fact that the Tabernacle is independent and not a state school. This has all sorts of consequences, one of which is that the school can focus on making good, well-educated children rather than, for instance, achieving a series of government targets. It also only survives if it gets results.

Dr McKenzie, headmaster of the Greater Miami Academy, ‘clearly born for the position’.

The Tabernacle – an independent, faith-based school – is one of a small but fast-increasing number of private schools for poor people. It is a remarkable phenomenon. There are state schools all over the country. They are free and government approved. But more and more people of limited means are giving up on them. They are paying high proportions of their incomes for schools with far more modest premises. Some observers assume it is all to do with the religious aspect of such schools, since nearly all of the new schools for poorer people are faith-based. But according to the people I have talked to who are involved in Christian and Muslim schools, this is not the case. It is primarily a question of parents like Grace Patterson wanting their children to be well educated and well behaved. They have come to feel that the state schools available to them would take their children down a different, dangerous path.

I asked Grace how she felt about sacrificing so much pay for the schooling of her two boys. She quietly said, ‘I will have my reward when I see my children’s success – walking in their success.’ I found meeting her a moving experience. There is no doubt in my mind that she saved her son from a bad life – a wonderful achievement.

The number of independent, faith-based schools like the Tabernacle is growing pell-mell, jumping recently from 170 to 276 – a rise of over 60 per cent in a single year. Muslim schools are to the fore, followed by Evangelical Christian ones. Anecdotal evidence suggests the trend is continuing. Numbers at the existing schools are probably growing, too. It seems likely that more than 11 per cent of all independent schools in Britain are now Jewish, Muslim or Evangelical and they generally cater to parents who are not at all well off. The growth of these schools is a symptom of the failure of state education. But it is also a sign that a growing number of people are willing to do something about it and to make something better. That is one of the little stars of hope.

*

My second story comes from the other side of the Atlantic.

After attending a conference in Miami, Florida in 2005, I took a taxi ride twelve miles inland through one of those huge expanses of small detached homes with ‘yards’ that typically surround American cities. Eventually I was delivered to a long, low building in a nondescript street. It proudly bore the name ‘Greater Miami Academy’.

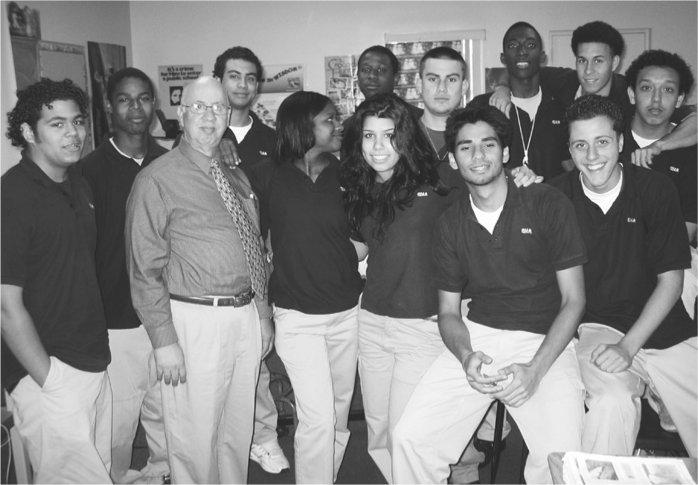

Dr McKenzie, headmaster of the Greater Miami Academy, ‘clearly born for the position’.

I was taken to meet the headmaster – a kind, open man, clearly born for the position he held. There was a complete absence in his manner of the defensiveness you often meet in British state school heads. Perhaps it was because he didn’t have to go along with government directives on what to teach, how to teach it and how to run the school. His school, like the Tabernacle in London, is independent. It is a fee-paying Seventh Day Adventist school.

I asked if I could speak to some of the children who were on a certain programme. Straight away he arranged it and, before long, four girls aged fifteen and sixteen trooped into his office. Each one shyly shook my hand and then they went to sit together, happily squashed on a sofa made for two.

I asked why their parents had arranged for them to leave the government-run schools where they had been before in order to come to this school. They seemed shy and, at first, none of them spoke. So I looked at one girl in particular and tried again. Denise Balladares, perched on the left corner of the sofa, hesitantly said, ‘They bring weapons … drugs. I saw guns…’

She was reluctant to expand. I turned to another member of the quartet.

Yahaira Perlazza, squeezed onto the right-hand side of the sofa, with long, dark hair and looking more streetwise than the others, said that students at her previous school ‘would get drugged’. Then she added that, academically, she was finding it ‘more challenging’ at the Greater Miami Academy.

One by one, all four told similar stories. All said that there had been drugs at their previous schools. ‘A lot of drugs,’ said Geniver Matamoro. ‘I told my mom and she sent me here. My grades are a lot higher and I’m learning a lot more.’ Most of them also told of seeing guns, knives or both.

It was clear, as with the Tabernacle, that the primary reason why parents had sent their children to this school was not religious at all. It was not even academic – though they had enjoyed a clear benefit from getting a better education. But first and foremost, the parents had wanted to save their children from present danger and also, very probably, to steer them away from an environment which could easily damage them for life.

I asked the four girls how their lives and expectations compared with how they would have been if they had stayed at their previous, government-run schools. Denise said, ‘If I had stayed where I was, I would be a completely different person. There were so many temptations.’ She did not define the ‘temptations’, but this came straight after many references to drugs.

Elizabeth said that previously she would have expected to go to a ‘medium college’. But now she might go somewhere like Columbia, one of the most celebrated universities in America. She said she now expected to have a good family and job when she grew up. Evidently that’s not what she expected before.

Each one told a similar story. Their academic expectations had jumped. They were safe, whereas before they were in danger. And the direction in which their lives were previously going had been transformed.

I can’t resist mentioning one unusual feature of the school. It might seem irrelevant, at first. But perhaps it isn’t. I visited a few classrooms and came across Yahaira, one of the girls I had interviewed, being taught aviation. The teacher was a lively, charming middle-aged man – another natural teacher. He was obviously enjoying himself and inspiring his students. But why aviation?

Well, the school happens to be close to an airport. There the students can get practical instruction. They had managed to obtain a second-hand flight simulator. If you are going to inspire children – including ones from difficult backgrounds – to become interested in education, aviation is a good bet. For some boys in particular, the idea of getting to fly planes is likely to seem ‘cool’ in a way that history isn’t.

The aviation class. Yahaira Perlaza is third from the right in the front row.

Getting airborne involved learning about weather patterns and aircraft engines. It means learning some geometry, geography and mapreading. The more I thought about it, the more aviation seemed an inspired idea for a subject. A few of the boys in the class planned to become airline pilots. They were getting leg-ups to good jobs. It is hard to resist the idea that it was the independent status of this school which allowed it the freedom, the imagination and, you might even say, the joie de vivre to go for it.

The Greater Miami Academy – like the Tabernacle School in London – is turning children’s lives around. Both are simultaneously also making their respective societies a little more civilised and safer than they would otherwise be. But why do I tell the story of the Greater Miami Academy, when it is similar in many ways to the one about the Tabernacle School?

There is one key difference. In Britain, Grace Patterson got her son out of a state school by making positively heroic financial sacrifices. But in Florida, the parents of Yahaira, Elizabeth, Denise and Geniver – though they are required to make a financial contribution – have not had to pay anything like the full cost of their children’s independent education.

First, the fees for all the children are subsidised by the church which sponsors it. Second, these children are on a programme paid for by Florida Pride, an organisation funded by companies as an alternative to paying tax. The ‘choice’ programme is one of several in Florida. Another is called the Opportunity Scholarship programme, which is for children in demonstrably failing schools. The biggest scheme is the McKay Scholarships programme, for disabled pupils.

Many other states in America have ‘choice’ programmes. The movement is growing. As this is America, the supporters of the idea are determined and well organised. And yet it is clear that the numbers involved are still small in relation to the whole school age population.

It is important to understand why. It is because it has been an uphill political battle to get such programmes accepted. There has been equally determined opposition to these programmes from teachers’ unions and some newspapers and politicians. These organisations and individuals have been against education paid for mainly by state governments but not run by them. These independent schools, of course, are not under the influence of teachers’ unions to anything like the extent of government- run ones. The main difference between the Tabernacle School and the Greater Miami Academy is that one consists of complete opting out from education supplied by the state, while the other is an attempt by government to channel tax dollars to private education.

Unfortunately, neither story leads towards an easy, uncontroversial answer to the problems of government education. In the British example, parents like Grace are paying twice for education and paying heavily. We must also remember that Grace Patterson’s actions derived from the terrible failure of a state school. One can hardly plan a future for education based on widespread failure engulfing thousands of other children. Meanwhile, in Florida, the choice programmes are hemmed in by fierce opposition.

Such little stars of hope – even though they are growing in number – are still few. But they are certainly better than a completely dark sky.