chapter one

rebellion into money

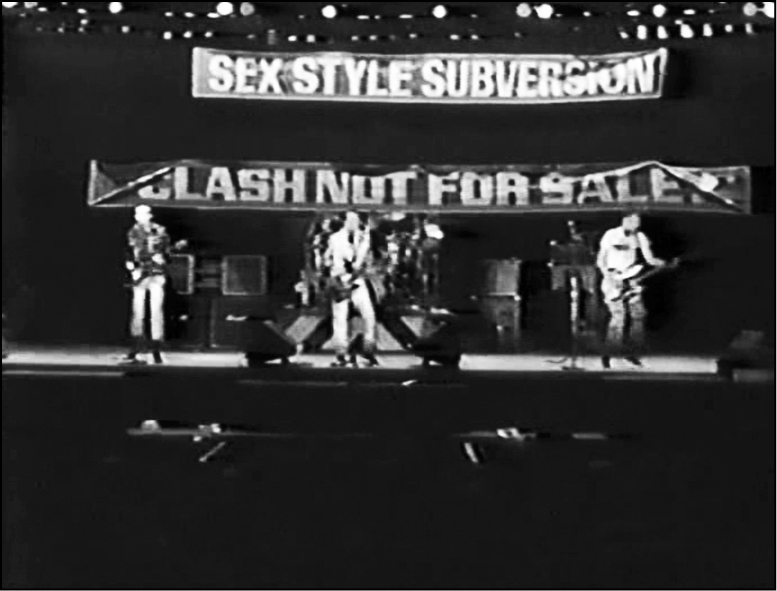

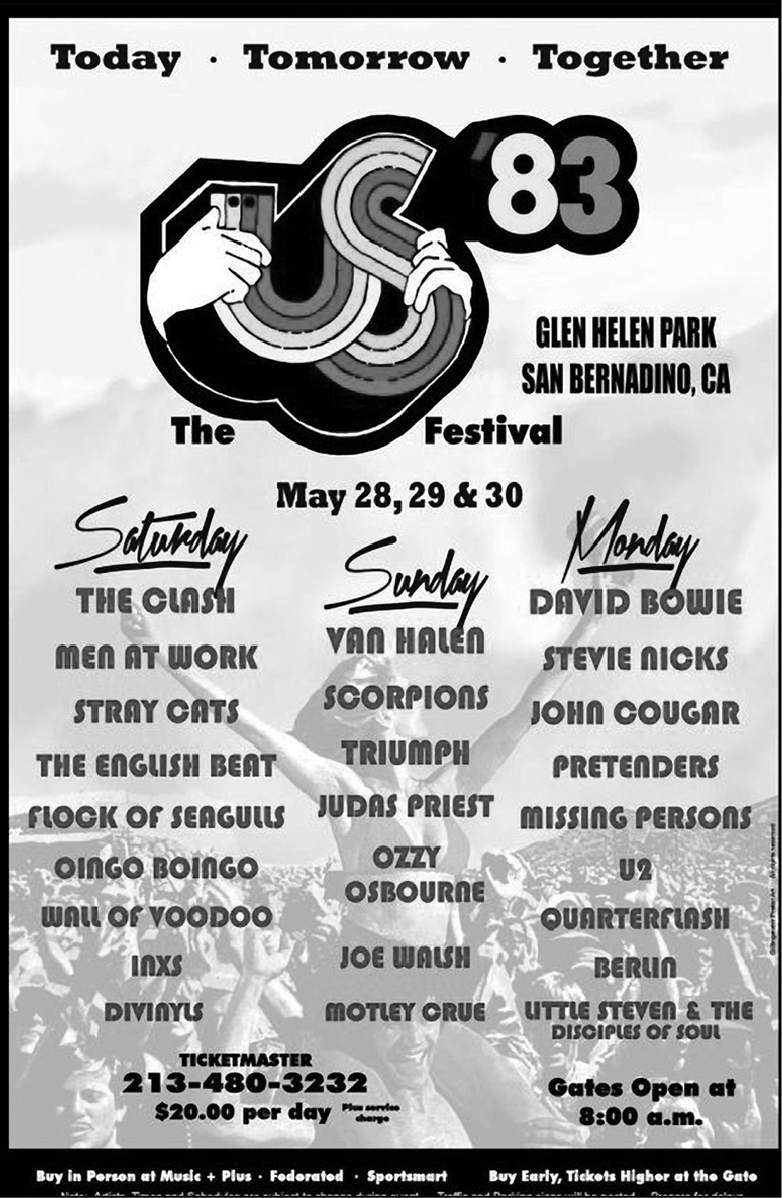

“Come on, I need some hostility here . . .” Joe Strummer onstage, US Festival, May 28, 1983. (Photographer unknown.)

US Festival, May 28, 1983. (Photographer unknown.)

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope.

—Margaret Thatcher, May 4, 1979

This here set of music is now dedicated to making sure that those people in the crowd who have children, there is something left for them later in the century.

—Joe Strummer, US Festival, May 28, 1983

The scene reeked of glorious rock spectacle.

Once scruffy denizens of British squats, tower blocks, and underground dives, The Clash today occupied the center of the musical universe. Standing on a massive outdoor stage, the band was dwarfed by more than 250,000 people. The roar of the sweating, surging crowd washed over the four slender figures.

From the back of the audience, the musicians seemed tiny ants on a stage, a pinprick of light, sound, and motion. A gigantic video screen provided the only opportunity for most listeners to connect actual human beings to the tsunami of guitar, bass, drums, and voice being flung at them in the darkness of the arena grounds of the US Festival, near San Bernardino, California.

“Unite Us in Song,” the festival’s advance publicity had said. The crowd, spurred by music, merged into a writhing rhythmic beast. Holy or unholy, some sort of communion was real here at this instant, in this place.

This should have been a moment of triumph for The Clash, a time to savor immense popularity won over seven hard years of touring, recording, and wrangling with an often mystified major record label. But as lead vocalist Joe Strummer strode to the microphone midway through the set, his words and demeanor suggested anything but self-satisfaction.

“I suppose you don’t want to hear me go on about this and that and what’s up my ass, huh?” the singer sneered. As the crowd cheered incongruously, Strummer continued: “Try this on for size—Well, hi everybody, ain’t it groovy? Ain’t you sick of hearing that for the last 150 years?”

A renewed roar greeted this dismissal, but what did the sound and fury signify? Affirmation? Noncomprehension? Determination to party on no matter what?

Strummer’s tone shifted to pained earnestness: “I know you are all standing there looking at the stage but I’m here to tell you that the people that are on this stage, and are gonna come on, and have been on it already, we’re nowhere, absolutely nowhere. Can you understand that?” The singer nodded to his bandmates, and muttered, “Let’s do this number!” The quartet crashed into “Safe European Home,” a sardonic, self-deprecating comment on “third world” violence and “first world” cowardice.

Strummer’s words evoked punk’s “anti-star” idealism. Yet the members of The Clash stood on that stage as rock stars paid—as the singer boasted later—half a million dollars for barely more than an hour of work.

If the scene evoked untrammeled success, the singer’s apparent anguish suggested something darker and more conflicted. Was this evening, ultimately, anything more than a lucrative commercial transaction?

In the eighty minutes The Clash played that night, one could have driven west from the festival grounds on Route I-10 and pulled in front of a handsome mansion in Pacific Palisades, a coastal neighborhood on LA’s west side.

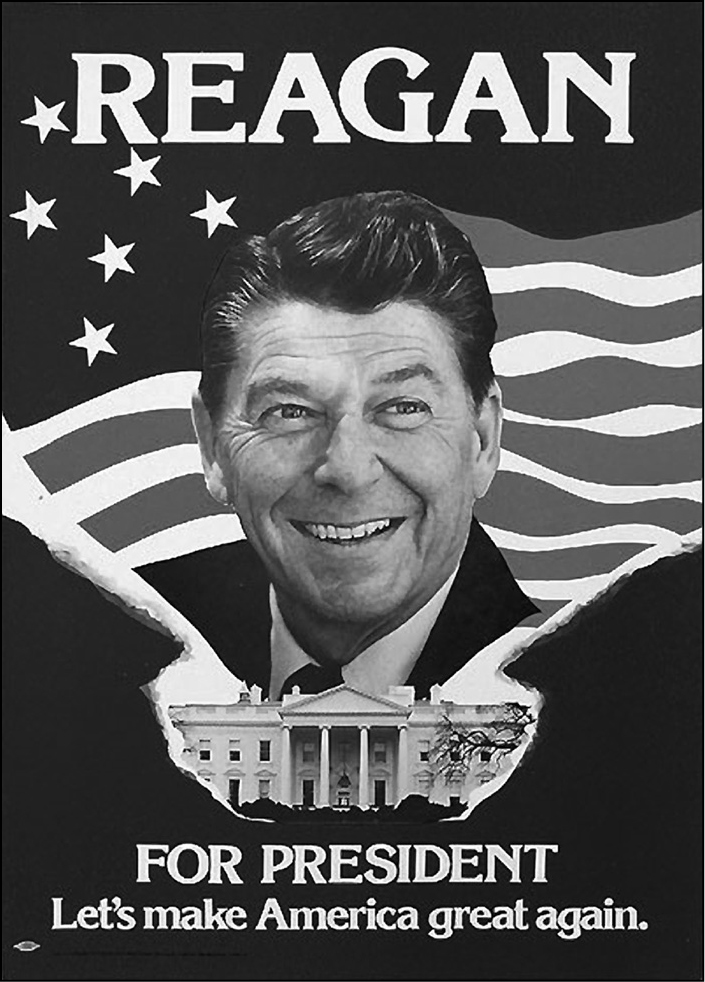

This house was where a transplanted Midwesterner had begun a transformation from aging B-list actor to right-wing icon to governor to, finally, the most powerful man in the world: the president of the United States. Now Ronald Reagan was preparing for a final political campaign, one that in eighteen months would determine whether he’d get another four years to consolidate his counterrevolution.

Across the Atlantic in The Clash’s homeland, an equally momentous campaign was already well underway. In twelve days, more than thirty million British voters would decide whether to keep Margaret Thatcher as prime minister. Sharing a quasi-religious faith in the “free market” and enmity toward “big government,” the two had become partners in what British journalist Nicholas Wapshott described as “a political marriage” that sought to change the world.

Conventional wisdom had dismissed Reagan and Thatcher as fringe figures, unlikely to be elected, much less be successful in implementing their creed. As Wapshott noted in a Reuters op-ed, “When Margaret Thatcher met Ronald Reagan in April 1975, neither was in their first flush of youth. She was fifty and he sixty-five. She was the leader of Britain’s opposition; he a former governor of California. It was by no means obvious that either would win power. They bonded instantly. Although born almost a generation and an ocean and continent apart, they found they were completing each other’s sentences.”

While both held to a conservative Christian faith that was then beginning to gain political ascendancy in the US via Jerry Falwell’s “Moral Majority” movement, they also bonded around another shared inspiration. As Wapshott makes clear, “Both found validation for their convictions in the works of Friedrich Hayek, at that time a long-forgotten theorist even among conservatives.”

Hayek was an Austrian economist who had famously contended with Britain’s John Maynard Keynes amid the Great Depression over whether government intervention would ease or prolong the economic turmoil. Hayek had extolled allowing the “free market” to correct itself over time. Arguing that “in the long run, we are all dead,” Keynes espoused ideas about the crucial role of government action which became the basis for much of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal.

The vanquished Hayek turned further to the right during World War II. In 1944’s Road to Serfdom, he argued that not only did government meddling injure the economy but, indeed, was bound to lead to tyranny. Aided by the publication of an abridged Reader’s Digest edition in 1945, the book found an audience in a slowly building right-wing movement, including with both Reagan and Thatcher.

By 1983 the two were no longer outsiders—they were rulers with immense power on the world stage. They brought this once obscure Austrian economist—and contemporary acolytes like Milton Friedman—into the mainstream. Both now stood at the pinnacle of their respective careers, seeking to dismantle the New Deal and Britain’s socialist-leaning “welfare state” postwar consensus.

If punk offered a bleak forecast in 1976, by 1983 that dark possibility was being made real. Virtually all the other early trailblazers had fallen away. Now the successful but conflicted Clash was one of the last gangs in town, standard-bearer for a vision that took the postwar dream for granted, and sought to push beyond.

As such, Strummer might be viewed as the nemesis of Reagan and Thatcher, for the two politicians sought not the fulfillment of that dream, but its death. Yet all three in their distinct ways sought to transcend the post-1945 consensus.

Punk rock had always been about more than simply music. Born largely as a reaction to the self-indulgent excesses and perceived failure of the rock-and-revolution 1960s, it offered a blistering critique of idealism sold out or gone bad.

Punk’s “ruthless criticism of everything existing” spared no one, and could slip toward nihilist extremes. That made the idea of harnessing music for radical change a perilous venture. Yet beneath noisy blasts of illusion-shattering negation still lurked an unbending belief in the power of music to transform.

The Clash was defined by this sense of mission. Dubbed “the only band that matters” by record company PR, the band helped crystallize an affirmative, activist vision for punk.

If the early Clash track “Hate & War” encapsulated the band’s dismissal of the sixties, the musicians nonetheless borrowed from certain currents of that era. Their jagged, relentless music, close-cropped hair, quasi-military garb, and fierce sense of purpose suggested a marriage of Detroit agit-rock legends MC5 with the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

The Clash was fascinatingly—and sometimes infuriatingly—contradictory. They embodied punk’s “year zero” stance, dismissing the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Elvis Presley in “1977,” the B side of their debut single, “White Riot.” But if the incendiary songs warned of class war, they were made possible through the largesse of CBS Records, then one of the music industry’s behemoths.

“Punk died the day The Clash signed to CBS!” punk scribe Mark Perry famously declared in 1977. Although proved false by what followed, Perry’s words nonetheless suggested both The Clash’s immense meaning and contradiction: it wanted to be the biggest rock band in the world while somehow remaining “death or glory” heralds of revolution. If this paradox earned The Clash more than its share of criticism, it was also grounded in idealism that was real enough to cause anguish for the man at the center of the maelstrom: Joe Strummer.

Lead singer/lyricist Strummer was not only the elder member of The Clash, but also its soul. Rising out of the British squat scene, he was fascinated by American folk radical Woody Guthrie as well as the dwindling embers of late-1960s revolt. Active with a rising roots-rock band, the 101ers—named after the band’s ramshackle squat—Strummer was wrenched out of his backward-gazing by a blistering Sex Pistols show in April 1976.

Shortly thereafter, he was poached from the 101ers by guitarist Mick Jones and bassist Paul Simonon to front their nascent punk unit. This gifted pair had fallen under the spell of agitator Bernard Rhodes, the catalyst for assembling the band and encouraging them to write about urgent sociopolitical issues.

If Sex Pistols lit the fuse of punk’s explosion, The Clash sought to guide the movement’s subsequent momentum in a constructive direction, making the implicit affirmation behind “no future” rants more explicit and convincing. “We never came to destroy,” Strummer noted to Melody Maker in 1978, adding years later in a punk retrospective, “We had hope in a sea of hopelessness.”

After the collapse of sixties rock idealism, this was a tricky line to walk. Strummer’s ambivalence showed in a March 1977 interview with Melody Maker’s Caroline Coon. Asked how potent a band can be in making political change, he responded, “Completely useless! Rock doesn’t change anything. But after saying that—and I’m just saying that because I want you to know that I haven’t got any illusions about anything, right—having said that, I still want to try to change things.”

Although The Clash was careful never to accept a narrow ideological label, it stood on the revolutionary socialist left, as the frontman acknowledged elsewhere. Given this anticapitalist stance, Strummer admitted to Coon—who later would briefly manage the band after the ouster of Rhodes in late 1978—“Signing that contract [with CBS] did bother me a lot.”

Despite its underground roots, The Clash was not interested in being captured by a narrow subculture. If the Top 10 beckoned, it was in hopes of bringing a message of radical change to the broadest possible segment of the population.

In retrospect, The Clash’s signing to a major label like CBS seems preordained. Capitalism would provide the avenue for reaching the masses that then, in principle, could be mobilized to overturn that same system and build something better. CBS had been home to Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, and other sixties counterculture icons, and even issued an ad claiming “The Man Can’t Bust Our Music” in 1968. Already thinly disguised folderol at the time, by the midseventies, such rhetoric could sound dubious indeed. The Clash pressed on nonetheless.

Punks were not the only rebels who strode onto the world stage in the midseventies, however. At the very moment the Republican Party seemed eviscerated by the Watergate scandal, with the Keynesian postwar order appearing unassailable, grassroots insurgent Ronald Reagan was challenging Republican president Gerald Ford, and “strange rebel” Margaret Thatcher had just captured the leadership of the Conservative Party in the UK.

Reagan came to political prominence with his 1964 “A Time for Choosing” speech on behalf of the presidential candidacy of archconservative Barry Goldwater. While Lyndon Johnson won the contest in a landslide, Reagan used his notoriety as a springboard for a successful race for governor of California.

Reagan established himself as the deadly enemy of student radicals protesting the Vietnam War, famously proclaiming, “If there has to be a bloodbath, then let’s get it over with.” In 1976, Reagan’s upstart primary challenge to President Gerald Ford fell just short of victory. Four years later, Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter, who was wounded by inflation and the Iranian hostage crisis. Reagan accomplished what his mentor Goldwater had failed to do nearly two decades earlier: bring a newly radicalized Republican Party into the White House.

Over the same period, Thatcher had gone from Parliament backbencher to minister of education in the middle-of-the-road Tory government of Edward Heath. She slashed milk subsidies to schoolchildren, and showed no remorse when protesters chanted, “Thatcher Thatcher, milk snatcher!”

Thatcher watched not one but two Tory defeats by the militant National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), in 1972 and 1974. Led by rising Marxist firebrand Arthur Scargill, squads of “flying pickets”—unionists dispatched to blockade strategic locations—not only shut down the UK power grid but also brought down the Conservative Party–led government.

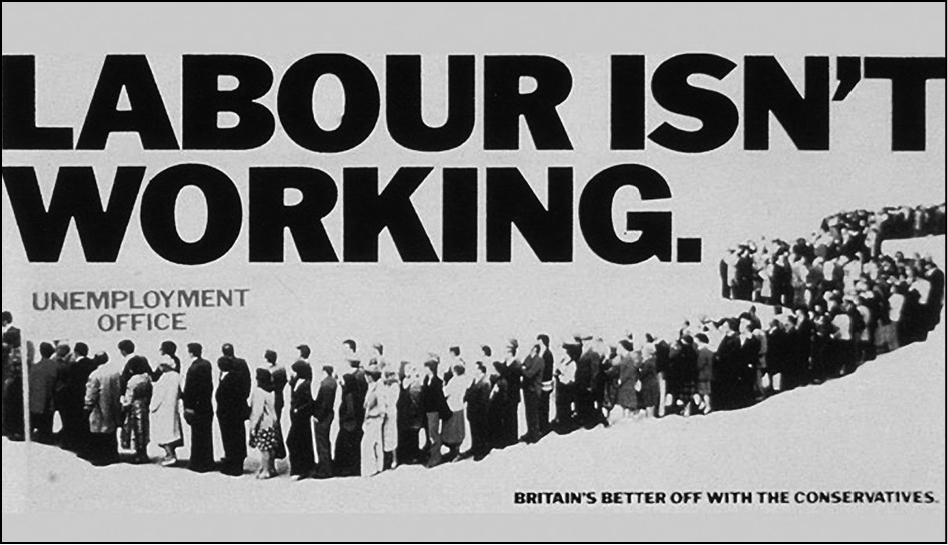

While Thatcher absorbed lessons from the lost battles, she was also there to claim the leadership of the party in 1975 in their aftermath. It was a lucky moment to ascend, for the Labour Party would squander its own turn in power amid economic stagnation and social turmoil. Unemployment and inflation rose, mounds of garbage piled up, and transportation was paralyzed by a series of strikes. “Labour Isn’t Working” was Thatcher’s catchiest campaign slogan.

Thatcher’s most resonant 1979 ad, by Saatchi & Saatchi.

A different take on Margaret Thatcher by an anonymous artist.

Capitalizing on the ennui, Thatcher became prime minister on May 4, 1979. She promised healing, quoting the soothing words of St. Francis of Assisi as protesters confronted the police massed outside the compound. Her radical agenda, however, would create divisions not seen in the UK since the 1600s.

Thatcher came to power determined to complete a mission. Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren had approvingly quoted anarchist revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin’s dictum, “The destructive urge is also a creative urge,” during the heady days of punk’s birth. With Thatcher and Reagan’s rise, another form of “creative destruction” had now arrived: the “free market.”

Ironically, Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter had derived the term from the work of Karl Marx. For Marx, “creative destruction” meant that capitalism sowed the seeds of its own downfall. But the phrase became used within “neoliberal” (a.k.a. “free market”) circles to describe actions like slashing jobs at a company in order to increase its efficiency and, in principle, also that of the larger economy.

This process had been at the heart of the wrenching transformation generated by the Industrial Revolution, and was central to capitalism. If essential for economic growth and progress, the cost in human terms could be immense.

This conservative surge provided the backdrop for The Clash’s rise. The tension between the band’s aims and its means led to new groups such as anarchist trailblazer Crass. While inspired by The Clash, these bands were hostile to their compromises, with Crass cofounder Penny Rimbaud noting that “CBS promotes The Clash—but it ain’t for revolution, it’s just for cash.” Strummer countered by calling Crass “a storm in a teacup,” deeming their do-it-yourself stance as “self-defeating, ’cos you’ve got to be heard.”

The Clash’s third album, London Calling, challenged a version of punk that could seem ever more narrow. As Strummer groused, “I don’t want to see punk as preplanned and pre-thought-out for you to slip into comfortably like mod or hippie music or Teddy Boy rock and roll. In ’76 it was all individual. There was a common ground, it was punk, but everything was okay. Punk’s now become ‘he’s shouting in Cockney making no attempt to sing from the heart and the guitarist is deliberately playing monotonously and they’re all playing as fast as possible so this is punk’ . . . God help us, have we done all that to get here?”

To Strummer, punk was a spirit, an approach to life, not a set of clothes, a haircut, or even a style of music. This was possibly convenient for the band’s commercial aims, but his critique rang true. Soon many of The Clash’s hard-core underground punk critics would find themselves striving to transcend self-made straitjackets.

With London Calling—released only six months after Thatcher’s election—The Clash began to stake its claim on the broader arena of mainstream rock and roll. The musicians abandoned their early disavowal of prepunk sounds for a fervent embrace of the many forms and faces of rebel music. Spurred on by a catchy but lyrically lightweight hit single, “Train in Vain,” the album rose almost into the American Top 20, an unprecedented level of success for a left-wing punk band.

The band’s ambitious vision was made even clearer by the following triple-album set, Sandinista! It sought to articulate—with wildly varying degrees of success—a world music that spanned jazz, salsa, reggae, funk, rap, folk, steel drum, disco, and rock, united only by a common grassroots focus and radical politics.

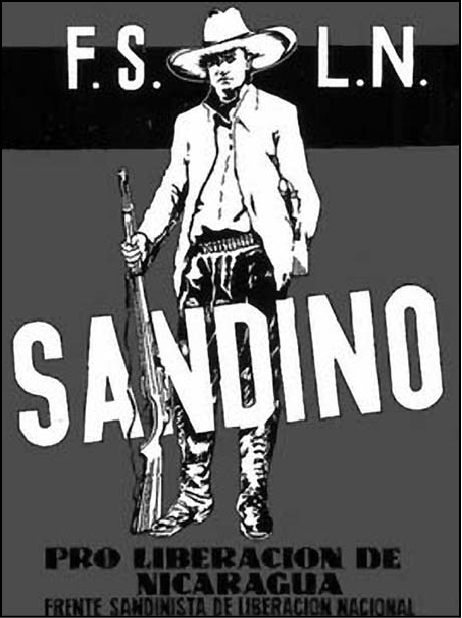

The latter was announced by the album’s title, an approving nod to Nicaragua’s Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN). Popularly known as the Sandinistas, they were Marxist revolutionaries who had overthrown a US-backed military dictatorship in a popular insurrection in 1979.

Strummer first learned about the Sandinistas from an old friend, Vietnam veteran/activist Moe Armstrong. Later he recalled, “Moe [gave us] info that was quite hard to find out. A bunch of teenage Marxists oust your favorite dictator? The establishment don’t want to know!” Impressed by the quasi-punk spirit of the youthful revolutionaries, as well as initiatives like a mass literacy campaign and health care advances, Strummer and the band took up their cause.

The song “Washington Bullets” provided the album’s title, rebuking the US—as well as the UK—for supporting dictatorships. It was no simple anti-American screed, for it also celebrated Jimmy Carter’s commitment to human rights that had led the US not to intervene to stop the Sandinistas’ victory. Articulating a consistent anti-imperialist stance, Strummer also skewered the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Chinese occupation of Tibet over a bubbling salsa beat.

Augusto César Sandino, who fought against the US occupation of Nicaragua, 1927–33.

Massive crowd in the main square of Managua, Nicaragua, after the Sandinista victory, July 20, 1979.

By the time Sandinista! was released in the US in January 1981, however, the Carter administration and its human rights policy were on its way out. In its place was the newly elected Reagan administration, whose more muscular approach was driven by a rabid anticommunism that viewed conflicts around the world through the prism of superpower competition with the Soviet Union.

“Dictatorships and Double Standards,” an essay by Jeanne Kirkpatrick, a former Democrat turned neoconservative hawk, informed Reagan’s Central American policy. Kirkpatrick argued that Carter’s human rights emphasis was fatally misguided. By abandoning authoritarian allies like Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua or the shah of Iran, the US was naively opening the way for the expansion of Soviet-backed totalitarianism, and thus not only injuring our strategic interests but also, ultimately, the cause of human rights and democracy.

Reagan’s decision to make Kirkpatrick his ambassador to the United Nations—an institution that she largely held in contempt—sent a clear message that human rights was no longer a priority for US foreign policy.

While the Sandinistas had ample reason to worry about this shift, an ugly preview of bloodbaths to come first materialized in neighboring El Salvador. Kirkpatrick had already identified that country—which bordered Nicaragua, and was in the throes of its own nascent civil war, with Marxist-led guerrilla groups fighting a military-backed regime—as the next battlefront in a global war against Soviet communism. With Reagan’s 1980 victory, his spokespeople made it clear that there would be no hands-off approach in El Salvador as with Carter in Nicaragua.

According to Robert White, Carter’s ambassador in El Salvador, Salvadoran elites took Reagan’s victory as a green light for a murder spree shocking even for a country where Archbishop Oscar Romero had been assassinated only eight months before. In swift succession, the leadership of the peaceful opposition was abducted, tortured, and killed, followed by rape and murder of four North American churchwomen, and, finally, the execution of the head of the Salvadoran land reform agency and two US advisers in the lobby of the Sheraton hotel.

When White spoke out against these horrors and subsequent efforts to cover up the role of the Salvadoran military, he was summarily dismissed. Reagan swiftly put forward a request for millions of dollars of military aid for the government. The conflict intensified and the body count mounted, rising quickly into the thousands.

The Reagan administration’s savage debut could hardly be expected to pass unnoticed in the Clash camp. A response would be forthcoming, but the band was then preoccupied with other matters.

The Clash had created headaches for its corporate sponsors as early as 1977 with “Complete Control,” which lambasted company machinations in brutally direct terms. Likewise, the band won few friends at CBS with its insistence on first putting out the double-LP London Calling for the price of a single album, then upping the wager with the three-for-the-price-of-one Sandinista!

CBS had grudgingly agreed. But Sandinista! held no breakthrough singles on any of its six sides, had received mixed reviews, and sold no better than London Calling. The band had foregone royalties in order to get its bargain price. Now debts to the record company were mounting.

As pressure built, a management shake-up pushed by Strummer and Simonon brought Bernard Rhodes back in early 1981. It would prove to be a fateful shift.

Rhodes was hardly a typical rock impresario, and his approach was anything but diplomatic. According to Clash insider The Baker, “The fundamental mistake everyone makes is in viewing Bernie as just the manager. But it was Bernie’s vision that inspired the entire concept of The Clash. He crafted them, fathered them, pulling them one by one from their respective situations and putting them together like ingredients in a grand recipe. Their early political ideologies, fashion concepts, and total image were a statement of Bernie’s thought processes.”

If Rhodes was central to The Clash, his roughshod manner had alienated most of the band—especially Jones—and led to his firing. The Clash flourished artistically and commercially during his exile, with first Coon and then sixties holdover Blackhill Enterprises in the managerial role. Yet the growing tension between radical intent and commercial ambition left Strummer in particular feeling uneasy.

In Rhodes’s absence, Jones had assumed control in the band. Strummer felt sidelined and—after the critical savaging of Sandinista!—concerned for the band’s direction. As The Baker recalls, “The excesses of Mick’s musical domination resulted in angst-ridden turmoil within Joe. Certain that The Clash had deviated badly from their intended goals, he turned to the only person that he felt was still championing those original political and cultural ideologies: Bernie Rhodes!”

At the same time, band mouthpiece Kosmo Vinyl argues simply, “Bernie was brought back to break The Clash in America, and I worked with him to make that happen.” However counterintuitive this may seem, The Baker agrees: “Bernie was given a mandate: make the band huge, sell as many records as possible, get the message out to as many people around the world as possible—but do that without having the band’s message watered down to puerile pop nonsense.”

This seems an unlikely role for the abrasive radical. But Strummer believed Rhodes could accomplish this breakthrough while somehow keeping the band true in a revolutionary sense more than could the “professionals” at Blackhill.

In 1982, Strummer would explain to journalist Lisa Robinson, “It’s like having a split personality. I want The Clash to get bigger because you want people to hear your songs, you want to be successful . . . But on the other hand, I’m pretty wary of that, of having it get too big to handle. You always think you can handle it, but you never know.”

The Baker elaborates: “Joe wanted The Clash to reach the top, and yet not become part of the industry that they so despised. It was a tall order, and a very noble cause. Elvis, Beatles, and the Rolling Stones—they all became product, packaged and sold. Could it be avoided? Joe wanted to try.”

In The Clash’s 1978 anthem “White Man in Hammersmith Palais,” Strummer had written about other punk bands “turning rebellion into money.” If The Clash did break through, how could it evade that trap? Strummer wasn’t sure—but regarding Rhodes not only as a political catalyst but as a surrogate father, he trusted him to navigate the treacherous straits.

Jones was not as hopeful that Rhodes would bring commercial success, but he also was not as nervous about the idea of rock stardom. Indeed, he had groomed himself for just such a role, as a kid from a broken home, living with his grandmother in a tower block. Vinyl—who had been with Blackhill, but who continued on with The Clash after the return of Rhodes—explains, “Mick was one of those kids who locked himself in a room, listening to the Stones, Mott the Hoople, whomever, practicing his guitar, dreaming of living that rock star life.”

The Baker agrees: “Joe was from the squat scene, Woody Guthrie and all that, but Mick came from an old-school rock background, openly idolized bands like Mott the Hoople and the Stones.” When asked why “1977” declared, “No Elvis, Beatles, or Rolling Stones,” by a fanzine writer in October of that year, Jones grinned and replied, “Well, you gotta say all that stuff, ain’t ya?”

Both Vinyl and The Baker hasten to add that this did not mean Jones was not committed to the Clash political vision, only that his attitude toward the fruits of success was much less fraught than that of Strummer or Simonon. Such differences meant little when the band was an underground punk phenomenon, but would become a flash point as its popularity grew.

* * *

As The Clash considered its next steps, Thatcher was recovering from a bruising year where her popularity had dropped to historic lows amid a deep recession. The contraction had been caused largely by her monetarist economic policies, bitter medicine intended to cure a rising cost of living.

Beyond inflation, Thatcher had ripped Labour for the high rate of unemployment. Yet joblessness had been rising ever since her election. It neared three million by 1981’s end. Her critics were hardly surprised when urban riots broke out in Brixton and other low-income areas. Yet Thatcher was undeterred, asserting, “The lady’s not for turning,” despite pressure from within her own Tory ranks.

The pain was immense and undeniable: over two million jobs were lost in 1979–81. Particularly hard-hit was British Steel, the government-owned enterprise headed by Thatcher-appointee Ian MacGregor. He had returned after decades of living in the US to serve in this moment of “creative destruction” with downsizing, privatization, and closures high on his agenda.

MacGregor had presided over similar wrenching cutbacks in places like Youngstown, Ohio. As factories were shuttered, only to reopen with cheaper labor overseas, this US region gained a new nickname: the Rust Belt.

Thatcher was determined to “privatize” industries such as steel that had been nationalized after World War II as part of building a socialist state that sought to protect citizens from the cradle to the grave. Seeing only inefficiency and waste in this method, Thatcher valued MacGregor’s hard-nosed approach to labor relations and improving profitability, and brought him on the team to do this specific job. But dismal poll numbers suggested that she risked being not only the least popular prime minister in UK history, but also a short-lived one.

Thatcher promised “a short, sharp shock” as her policies went into effect, with renewed growth and vitality to come. Many were not convinced.

As disaffection and upheaval in Great Britain were building, the Rhodes-led Clash had become the toast of New York City and Paris, turning residencies at the Bonds nightclub and Theatre Mogador into artistic and publicity triumphs. The Clash was especially captivated by New York, and had begun work on a new album.

Vinyl recalls the recording sessions themselves going smoothly—but not so the efforts at mixing or finalizing the record. Jones was even more dominant in the sessions than usual. He presented a finished double album tentatively called Rat Patrol from Fort Bragg that Strummer, Simonon, and Rhodes considered lightweight and too long. So producer Glyn Johns, renowned for work with the Who, the Stones, and other big names, was brought in on a rescue mission.

An impressed Johns later recalled to Tape Op magazine, “Joe let me rip it to pieces!” The result was a stripped-back single album that left Jones angry and aghast. Strummer was unapologetic: “I brought in Glyn Johns and I think . . . well, it isn’t all good but he shook some real rock and roll out of that record.”

If the musical disagreements were ominous, a more urgent crisis was the growing drug dependency of drummer Topper Headon. Drug addiction was a rock and roll cliché by now, and one The Clash had blasted with some regularity, despite the band’s obvious affection not only for alcohol but also marijuana—a predilection made public in a 1979 feature in pot bible High Times.

In that article, Strummer identified heroin as a bane to the counterculture, echoing the longstanding Yippie distinction between “life” drugs like pot and psychedelics and “death” drugs like speed, cocaine, and, above all, heroin. Clash antiheroin commentary dated back to “Deny” on the first album through “Hateful” on London Calling and “Junkie Slip” on Sandinista! as well as a new track, “Ghetto Defendant.” Yet Headon fell prey precisely to this drug.

On an early 1982 tour of the Far East, Strummer confronted Headon: “How can I be singing all these antidrug songs with you stoned out of your head behind me?” Headon was unmoved, and the issue remained unresolved after the band’s return, through the drama over the new album’s length and production.

Then on April 21, 1982—three weeks before the new record was to be released and only days before a UK tour was to commence—Strummer disappeared.

Much has been written about the time the singer was missing in action. The disappearance had its genesis in a stunt suggested by Rhodes, apparently worried about weak advance ticket sales on the UK tour. But it turned into a genuine reflection of Strummer’s desperation over pressures from the band’s growing popularity, the deepening tension with Jones, and Headon’s addiction.

Although Vinyl was able to locate Strummer in Paris after three weeks and convince him to return to do a lengthy US tour, the price was Headon’s ejection. Original Clash drummer Terry Chimes stepped in with five days’ notice before the two-month tour began on May 29, 1982, in New Jersey.

It was a challenging development, most of all for Headon, who felt betrayed and abandoned. Vinyl recalls, “Topper was the best drummer of his generation, but he had no interest in giving up drugs. We had no choice.” The Baker disputes this, but admits, “The band couldn’t just wait for Topper . . . things were moving so fast.”

Strummer would later bitterly regret his decision, and date the demise of The Clash to this moment. Yet it’s hard to see what else could have been done—not if the band intended to preserve its credibility.

* * *

By the time this drama had played out within The Clash, the political ground had shifted—starting when Argentine military forces invaded and occupied the Falklands Islands on April 2, 1982. The Falklands were a somewhat embarrassing vestige of the faded British Empire. They were situated just off the coast of Argentina, which claimed them as “Las Malvinas.” While this Argentine assertion had history and geography on its side, the Falklands had been a British colony since 1841, and were largely populated by descendants of British settlers.

A series of errors had sparked the war. Budget cuts pushed by Thatcher led to British ships being removed from the South Atlantic, sending a signal that the Falklands were no longer a priority. Reagan emissary Vernon Walters subsequently assured the leadership of the Argentinian military dictatorship that in case of an invasion, “The British will huff, puff, protest, and do nothing.” And the Argentinian dictatorship apparently felt that reclaiming the Falklands/Malvinas would distract attention from economic troubles and political repression at home.

In the last instance, the junta was proved correct, at least at first. Argentinian nationalism was sparked by the bold act, and approval of the government soared. But the first two assumptions would prove less sound.

Given that Thatcher’s decisions had helped precipitate the Falklands conflict, the war could have dealt a deathblow to her unpopular regime. Thatcher’s risky decision to dispatch a naval task force on April 5 to retake the islands raised the stakes even further. But this gamble would be her political salvation.

As British troops went into combat, nationalist fervor built in the UK, especially as the war went well for the home team. A popular tabloid newspaper, the Sun—mouthpiece for right-wing media mogul Rupert Murdoch—offered a simple huge “GOTCHA” as a headline in response to the sinking of the Argentinian ship General Belgrano, at the cost of 368 lives. The Sun adjusted the headline after the immensity of the death count became known, but the paper—like most of the British press—continued its gung ho war coverage.

Vinyl saw this war fever engulf a pub that the band had long frequented: “It was really ugly. We had been drinking beside these guys for months, and felt they were alright geezers. All of a sudden they were cheering Thatcher, cheering for the deaths of hundreds of human beings, all because they were ‘the enemy.’ It was a bit sick, really, and we decided to take our business elsewhere.”

Thatcher adamantly opposed any resolution short of outright Argentinian surrender. This tested her relationship with Reagan, who was torn between their alliance and his support for the anticommunist Argentinian military dictators.

When Reagan sided with Thatcher, the outcome was certain. After ten weeks, and with nearly one thousand dead, the Union Jack once again flew over the Falklands. Thatcher emerged victorious, with dramatically increased popularity not only at home but abroad as well. The Argentinian dictatorship was soon deposed in a return to democracy, but for Thatcher the message was chilling: War works.

Among the many repercussions from this episode was a small one involving The Clash. At the last possible moment, Strummer decided to call the new album Combat Rock, intended as an oblique comment against the war then raging. It was a sign that Strummer’s artistic gaze—largely diverted to Central America, Vietnam, and New York City—might soon come to rest back home.

For now, there was little time for reflection. Combat Rock was released on May 14, 1982, and the reunited original version of The Clash hit the road two weeks later. The shows tended to downplay Sandinista! in favor of the new record, the London Calling LP, and early nuggets like “Career Opportunities” now containing a revised line: “I don’t want to go fighting in a Falklands street.” “Charlie Don’t Surf” was a key Sandinista! track aired from time to time, with Strummer explaining, “We thought this song was about Vietnam, until we discovered it was about the Falklands.”

The band played virtually every night for two months. Although Chimes was not Headon’s equal as a drummer, he was skilled and tireless, providing a hard-hitting foundation for the songs. One seasoned observer, Rolling Stone critic Mikal Gilmore, complimented the band on “some of the best shows in years.”

Any doubts about the Clash trajectory were quickly overwhelmed by the imperatives of touring. After the US tour, The Clash had only two weeks off before making up the UK dates dropped when Strummer went AWOL. After three weeks and eighteen gigs, The Clash went back to America for another three months.

Combat Rock itself could be seen as a more concentrated version of the musical formula debuted on Sandinista!, largely eschewing straight-ahead rock numbers for more angular and open compositions. When Rhodes critiqued the new material he heard in rehearsal as long meandering “ragas,” Strummer slyly incorporated the remark in the opening line of a new song, “Rock the Casbah.”

The album also echoed Sandinista!’s themes. That record had been given the catalog number “FSLN 1,” another nod to the Nicaraguan revolutionaries; Combat Rock now took “FMLN 2” as its number, a reference to the Salvadoran guerrilla coalition, the Farabundo Martí Front for National Liberation (FMLN).

The group was named after Salvadoran Communist leader Farabundo Martí, an ally of Nicaraguan revolutionary Augusto César Sandino, for whom the Sandinistas were named. Martí had led a peasant uprising against the military and oligarchy in 1932. It ended in “La Matanza” (The Massacre), with perhaps thirty thousand killed—including Martí—in less than a month in retaliation for the rebellion.

This slaughter found an echo in the mounting atrocities committed by the Salvadoran military, armed by the Reagan administration. In just one example, the Atlacatl Battalion—trained and advised by the US military—killed as many as one thousand men, women, and children suspected of supporting the guerrillas in the northern village of El Mozote on December 11, 1981. This single massacre equaled the entire death toll of the Falklands War.

When New York Times reporter Raymond Bonner helped expose these killings in January 1982, Reagan officials viciously attacked his objectivity, denying the atrocity had taken place. Amid intense pressure from the administration, Bonner was transferred to another post, and the slaughter went on.

If most of the US populace looked away, The Clash was paying attention, with sixties icon Allen Ginsberg adding references to Salvadoran death squads to Combat Rock’s “Ghetto Defendant.” As with Sandinista!, the ghost of the Vietnam War hovered over the record, even as El Salvador was in danger of becoming another such quagmire, with the US drawn again into defending a corrupt and brutal ally in the name of “fighting communism.”

Behind the scenes, the CIA was working to unify fractious anti-Sandinista counterrevolutionaries—known as “contras”—into a fighting force to harry and ultimately overthrow that regime. Using clandestine allies like Israel and Argentina, Reagan extended his backyard offensive throughout the Central American and Caribbean region.

As The Clash pressed its own campaign on the concert trail, a seismic shift was occurring. Combat Rock was garnering strong reviews, but even greater sales. First, “Should I Stay or Should I Go” ascended the charts, replicating the success of “Train in Vain” three years earlier. Then a new video music channel, MTV, sent a second single, “Rock the Casbah,” into the Top 10. The endless gigging was exhausting, but The Clash was breaking big in the largest market in the world, headlining larger and larger venues.

Then The Clash got an unusual offer: the Who wanted the upstart unit to join a “farewell” American tour. Commercially, this was a no-brainer, exposing The Clash to an audience far beyond their existing one. Artistically, the appeal was less certain. The Who represented the “dinosaur rock” The Clash had set out to displace, and the band would be on enemy turf, playing huge stadiums.

The Baker knew where he stood: “We were packing up the gear after a show and [Clash guitar tech] Digby said to me, ‘What’s going on in the dressing room? The door is locked and there’s no fans in there.’ I ran back to the dressing room and found the band in heated discussion with Bernie and Kosmo about the prospect of supporting the Who. At the time it seemed to me that Mick was for it, Paul was on the fence, and Joe seemed to be just listening, undecided. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing and resolved—against my better judgment—to offer my own protest even though I knew I was in danger of being told it was band business.”

The Baker cited all the obvious drawbacks, but to no avail: “The Bernie/Kosmo force majeure was pounding the table about ‘taking it to the next level’ and ‘competing with the music business on its own playing field.’ Tempers flared—I couldn’t believe we had come this far holding onto some of the most precious tenets of the early days, only to give in to big business. I was accused of being ‘unrealistic’ and trying to live in the past.”

When Rhodes shouted, “This ain’t fucking 1976!” The Baker gave up and stormed out of the dressing room. If beaten in the argument, he remained skeptical: “I felt Joe knew they were making a mistake but that there was nothing else to do. His unshakable trust in Bernie’s instincts once again won the day.”

In the end, the band decided it couldn’t turn down the money or the challenge. But it was one thing to decide to do it, and another to actually play on gigantic stages to a distant audience, many of whom had not come to see The Clash, and who were impatient to see the headliners.

The Clash had played to big crowds before, including some 80,000-plus in London’s Victoria Park for Rock Against Racism on April 30, 1978. That gig, however, had a political urgency and purpose, helping to defeat a rising neo-Nazi threat in the form of the National Front, amid acts of racist violence.

One of those in attendance was a teenage Clash fan named Billy Bragg. Years later, Bragg would recall, “That was the first political activism I ever took part in, and I went because The Clash were playing. It totally changed my perspective. There were 100,000 kids just like me. And I realized that I wasn’t the only person who felt this way. It was that gig—and that audience, really—that gave me the courage of my convictions, to start speaking out.”

Bragg was not alone in feeling the day was a transformative experience. In 2008, leading UK newspaper the Guardian wrote, “For those who attended the concert in 1978 it was a show that changed their lives and helped change Britain. Rock Against Racism radicalized a generation, it showed that music could do more than just entertain: it could make a difference.”

Victoria Park carried an extraordinary resonance—but Strummer found that stadium shows rarely had such a vibe. They were engineered to include as many fans, and make as much money, as possible, with little thought to the quality of the experience. Bands would generally be visible only on gigantic video screens, blurring the line between experiencing live music and watching TV.

This meant hard work for any group serious about connecting with its audience, often resulting in an exhaustion that was more psychic than physical. The Clash was a band that fed off its fans, enjoying the chaos and spontaneity. The businesslike tick-tock of these huge shows was alien to them, and the immense distance from the audience took its toll.

At New York’s Shea Stadium, Strummer chided the crowd for chatting during the songs. After another gig, a visibly exhausted Strummer—sitting slouched over and hiding behind sunglasses—was asked about the band’s responsibility to the fans. He responded curtly, “I’m not strong enough to carry anything like that right now.” When the interviewer followed up with Jones, asking how he felt about the music industry, he replied, “It’s not any worse than any other prostitution business.”

That Jones would say this is striking because, of the band’s original cohort, he was perhaps the one most open to this level of success. It did not mean, however, that he handled the breakthrough well.

Jones had never been known for punctuality—in the movie Rude Boy he is scolded on camera by road manager Johnny Green—but after Combat Rock broke big, it got worse. Whether this was due to his late-night lifestyle or a power play is not clear. Whatever the cause, Jones regularly left the band waiting. Added to existing musical and ideological differences, a chasm was growing.

When the seemingly endless tour finally concluded just before Halloween 1982, The Clash was on top commercially, but battered spiritually. Moreover, Chimes did not wish to continue as drummer—nor did the band want to record new material with him, according to Vinyl.

After one last show in Jamaica on November 27, 1982, the band settled in for a lengthy break. Before recording Sandinista! the band had come off the road energized, eager to go to work writing new material, and even Combat Rock songs had come swiftly. Now everything felt different. There was no move to replace Chimes, and no plans were made even for rehearsals.

Ever eager for the stage, Strummer played a series of gigs with old friends—including Mole and Richard Dudanski from the 101ers—in an impromptu combo called the Soul Vendors. Both the band’s name and the raw roots-rock it played suggested the deep ambivalence Strummer felt about the commercial status and musical direction of The Clash, increasingly driven by Jones, whose interest in hip-hop and electronic music was growing.

Jones had begun using a guitar-synthesizer hybrid that Vinyl derisively dubbed “the dalek’s handbag,” referencing evil extraterrestrials in the Doctor Who TV series. Jones’s adventurous spirit had catapulted The Clash past most of its peers, asserting punk as far more than a static set of chords, hairstyles, and clothes. Now, it was not clear whether Strummer or Simonon wished to continue on that journey, at least in the direction Jones proposed.

When Strummer suddenly decided to make a ragged but engaging film noir, Hell W10, in early 1983, he enlisted friends and bandmates for the DIY endeavor. Strikingly, Jones was cast as the villain. For some participants like The Baker, the clues were too obvious to miss: “It was as if Joe knew that the only way they could keep working together was by not playing music.”

In the midst of editing the film, a call came with an astonishing offer: The Clash had been offered $500,000 to headline the first night of something called the US Festival, to be held near San Bernardino in Southern California.

The US Festival, which aspired to be “the Woodstock of the 1980s,” was the brainchild of American entrepreneur Steve Wozniak, cofounder of Apple Computers. The mountains of money being made in this emerging sector was contributing to fundamental shifts in the US and global economies—and allowed Wozniak to bankroll a huge festival costing untold millions of dollars.

Could that cash buy The Clash? The band had made a reputation by not being overly impressed by money and its temptations, even rebuffing the UK hit maker Top of the Pops because it required lip-synching. But if stadium shows were difficult, playing such a festival was a whole other animal.

In the sixties, the rock festival represented a “gathering of the tribes,” a communal celebration of the counterculture transcending a simple commercial transaction. Many were free, exemplifying a belief that music is for the people more than profit, for communion more than commerce.

But the intimate context that fed punk—with audience and band on essentially the same level—was worlds apart from the mass scale of rock festivals. Vinyl later noted, “Festivals are a hippie’s dream, but a punk’s nightmare.”

In 1989, Strummer articulated the punk ethic in praising the original 9:30 Club in Washington, DC, which had a legal capacity of 199: “I like tight spaces like this one where the crowd can feel the sweat splashing off the stage and you can look one another dead in the eye, take each other’s measure. It makes it all real, you know? Whatever it is, we’re doing something together, right in this spot, right now. It ain’t luxury, but it has some soul, like it was made for people, not cattle.”

The US Festival was going to be the sort of massive rock spectacle that made powerful communion difficult at best. But perhaps this was the moment for The Clash to take on the music biz on its own turf, a chance to stand up for “revolution rock.” Or maybe the money and momentum propelling them into the mass arena was too great to resist. Whatever the mix of motives, The Clash signed on.

Immediately the band faced a problem: there was no band. Seeing “the row brewing between Mick and the other two,” Chimes had definitively stepped back. Headon was still lost in his addiction. As a result, The Baker—none too excited about the show in the first place—was tasked with finding a skilled, relatively unknown replacement that could fit The Clash’s music, look, and mission.

The Baker knew there was no time for lengthy auditions. (The Clash had tried out perhaps one hundred drummers after Chimes left the first time, before settling on Headon in April 1977). He placed an ad in the April 23 issue of Melody Maker, and Peter Howard was one of those who answered the call. As The Baker remembers, “From the moment Pete walked into rehearsal he was so right for the Clash that it was an open-and-shut case . . . Musically, stylistically, and culturally, he was perfect for them.”

Howard was young, just twenty-three, but skilled. Although a casual fan of The Clash, he was not a devoted follower. “I’d seen The Clash, and I liked them, but I was not overawed. Headon was great, but my drum heroes were mostly prog-rock guys like Bill Bruford or Alan White, so I wasn’t intimidated.”

It was a high-pressure moment to be joining The Clash, and the managerial team of Rhodes and Vinyl were scarcely warm and fuzzy. Yet Howard seemed to hit it off with his rhythm-section mate Simonon, as well as The Baker who recalls, “With Pete’s arrival, it appeared possible that the dynamism, energy, and creativity could once again be ignited with the introduction of another element into the mix.”

As the Clash machinery revved up again, Strummer got some life-changing news: his partner Gaby Salter was pregnant. As Strummer’s relationship with his own parents was strained—having been consigned to boarding school, and losing his older brother to suicide—the immensity of becoming a father hit home.

Other members of The Clash were also experiencing massive changes in their personal lives. According to The Baker, “Paul had flown out to the US after we’d got Pete Howard and married his girlfriend, Pearl Harbour. Joe was now a father-to-be and was obviously feeling all the tensions that go along with that. Mick was fully ensconced at home with [his girlfriend] Daisy exploring new ground with his own alternative set of friends and their ‘creatures of the night’ scene which obviously flew in the face of the Bernie/Kosmo/Joe/Paul axis.”

* * *

As Strummer absorbed the big news, and The Clash hurried to break in the new drummer, another momentous change had taken place. On March 28, Thatcher’s new National Coal Board director was announced: Ian MacGregor.

MacGregor had headed British Steel since 1980, presiding over a radical restructuring: 166,000 people had jobs when MacGregor arrived; by the time he left for the Coal Board, only 71,000 were still there. More than 60 percent of the jobs in this British industry had just . . . disappeared.

Enterprises sheltered by government subsidy could run deficits eternally, bleeding the coffers dry. But not everything worth having showed up in the bottom line, of course, and there was serious social value to the jobs created.

For Thatcher, it was not worth the trade-off. In the long run, all would be best for the most, as the market made its magic happen—or so went the creed of the neoliberal faith. The choice of MacGregor to head the Coal Board meant the same medicine that had been given to steel was now to be administered to another pillar of the British economy. Arthur Scargill—now union president, having won election in 1981 with over 70 percent of the votes—declared, “The policies of this government are clear: to destroy the coal industry and the NUM.”

Meanwhile, Reagan had taken his rhetorical confrontation with the Soviet Union to an ominous new level. Speaking on March 8 to the National Association of Evangelicals in Orlando, Florida, Reagan extolled the power of prayer, and religion’s role in the founding of America. These paeans to the faith-based “greatness and the genius of America” were delivered while the administration was underwriting savage repression in El Salvador and beyond.

After denouncing abortion and supposed infringements on religious freedom by government bureaucrats, Reagan shifted to a new topic: the nuclear freeze movement trying to arrest the escalating arms race between the US and USSR.

Reagan claimed, “As good Marxist-Leninists, the Soviet leaders have openly declared that the only morality they recognize is that which will further their cause, which is world revolution.” He then asked the crowd to oppose a nuclear freeze that would only serve “the aggressive impulses of an evil empire . . . and remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong and good and evil.”

Such terms made war seem inevitable. While nuclear conflict might appear unthinkable, Reagan had argued in 1981 that such a war might be contained to Europe—a grim prospect for those who recalled World War II’s devastation.

As the stakes were rising on both sides of the Atlantic, The Clash hit the road, doing a series of smaller-scale shows in Texas and Arizona, warming up for the US Festival. The band was rusty, but Howard was proving himself as the new engine of the machine, with the power of Chimes and the finesse of Headon. The Baker: “In a way, Peter was a mix of the two . . . he fit like a glove.” Vinyl: “There were issues, there always are, but it was clear he could do the job.”

Yet tensions in the band were simmering. As Howard recalls, “I was the new guy, so I wasn’t privy to everything, but I could tell that Mick and Joe seemed hardly on speaking terms.” The choice of “Garageland”—a “we won’t forget where we came from” anthem written in response to signing with CBS—to open the first shows seemed to acknowledge a growing disconnect. Strummer was keen to demonstrate that The Clash remained true to its original mission.

Playing shows seemed to help ease the strain. The Clash was starting to hit its stride by the final warm-up in Tucson, Arizona. Strummer confronted overly aggressive security from the stage and joked about “the MTV curiosity seekers” in the packed house, but the band was hot and the crowd rapturous.

With the warm-up shows successfully completed, The Clash was on its way to the festival with spirits high, when reality hit them in the form of a huge Budweiser billboard in the desert promoting the US Festival. Such sponsorship was hardly unknown in rock and was rapidly becoming much more pervasive. Having signed to CBS years before, The Clash was by no means innocent of corporate marketing. Yet the band sought a certain distance to avoid compromising their politics and art.

The ad showed exactly what the band had signed up for, and The Baker remembers the mood on the bus darkening palpably. Strummer had already been joking about the juxtaposition, taking jabs at the other headliner, heavy metal party band Van Halen—which was getting $1 million to play, twice The Clash’s payment—from the stage at the show in Wichita Falls, Texas.

Now Rhodes tried to help by going on the attack. The festival’s techno-hippie vibe made it an easy target, and the decision was made to test the organizers’ utopianism. Although Wozniak would end up losing a huge amount of money on the festival, at the time that wasn’t anticipated. Rhodes challenged him to pony up $100,000 for a camp for at-risk youth or The Clash wouldn’t play.

Wozniak resisted what he saw as blackmail, given that The Clash had already signed a contract to play. At a last-minute press conference, the band pressed its threat not to play unless Wozniak came through with the donation. The audience was left waiting for nearly two hours until a compromise was found: the festival would give a token $10,000 contribution, and the band agreed to go on.

The band members were scarcely relaxed as they ran onstage, taking places in front of a gigantic banner proclaiming, THE CLASH NOT FOR SALE! If this seemed to protest too much, Strummer nonetheless greeted the massive crowd with a sardonic, “So here we are in the capital of the decadent US of A!” as the band plugged in.

In an earlier press conference with numerous other performers—where Van Halen lead singer David Lee Roth ribbed The Clash for being “too goddamn serious”—Vinyl had declined to comment on the festival itself, while making it clear “from the moment we hit the stage till the moment we leave, we will have something to say.” The band was no more than thirty seconds into the show, but the truth of Vinyl’s statement was apparent.

Perhaps thinking of his impending fatherhood, Strummer dedicated the Clash set “to making sure that those people in the crowd who have children, there is something left for them later in the century.” Then the band was off, igniting “London Calling,” followed swiftly by a fiery “Radio Clash” and a haunting “Somebody Got Murdered” with Jones on lead vocals. Strummer’s guitar was mixed higher than usual, providing an appealingly abrasive sound, with his ragged chording adding a raw edge to Jones’s more pristine tones.

Strummer had clearly come onstage intending to challenge the huge crowd as much as the event organizers. As soon as the third song died away, Strummer was back on the offensive: “Well, I know the human race is supposed to get down on its knees in front of all this new technology and kiss the microchip circuits, but it don’t impress me over much . . .” The singer hesitated, then launched another salvo: “There ain’t nothing but ‘you make, you buy, you die’—that’s the motto of America. You get born to buy it . . .” Leaping from critiquing consumerism to racial and economic inequality, Strummer continued: “And I tell you, those people out in East LA ain’t going to stay there forever. And if there is going to be anything in the future, it’s got to be from all parts of everything, not just one white way down the middle of the road!”

If the words were perhaps a bit incoherent, Strummer’s passion was plain. As the crowd tried to absorb the message, the singer tossed off one last exhortation—“So if anybody out there ever grows up, for fuck sake!”—and the band was off into their hit single “Rock the Casbah,” followed by the hard-hitting numbers “Guns of Brixton,” “Know Your Rights,” “Koka Kola,” and “Hate & War.”

Slowing the pace, Strummer introduced “Armagideon Time” as “the F-Plan Beverly Hills reggae song,” referring to a fad diet popular at the time. This quip turned serious as Strummer evoked the famine building in the Horn of Africa by extemporizing about “the Ethiopian Diet, lose five hundred pounds, success guaranteed, or your money back—yes, your money back” over a spooky dub groove. As he returned to the “a lot of people won’t get no supper tonight / a lot of people won’t get no justice tonight” refrain, the band—led by Jones—brought the song to an ominous close with splashes of dissonant guitars and drums.

If the music was strong, the singer found the audience response wanting. As applause washed over the stage, Strummer retorted, “Bollocks, bollocks! Come on, you don’t have to fake. You spent twenty-five dollars to go out there, so do what you like . . .”

The puzzled crowd responded uncertainly. Strummer upped the ante: “A lot of you seem to have speech operations, can’t talk or shout back or anything.” Balling up his fists, seeming desperate to somehow touch the distant mass, the snarling frontman baited the audience: “Come on, I need some hostility here . . . RRRRAAAWRRR! I need some feeling of some sort!” Then his tone lightened: “As it’s Sunday tomorrow, I hope you will join me . . .” The zinger led into a rollicking version of Sandinista!’s “The Sound of Sinners,” an amiable—but eminently forgettable—bit of gospel rock and roll. Self-deprecation, spoof, and sincerity mixed freely in lines like, “After all this time to believe in Jesus / after all those drugs / I thought I was Him,” before concluding, “I ain’t good enough / I ain’t clean enough / to be Him.”

It seemed something of an odd choice. Strummer, however, had a spiritual side, with radical bits of Christianity coming in largely through the Rastafari faith that imbued the band’s reggae covers. His past inspiration, Woody Guthrie, sang of Jesus as a revolutionary standing against the powers-that-be: “Jesus said to the rich / give your goods to the poor / so they put Jesus Christ in his grave.”

This view was backed up by history, and was shared by many believers. Priests and nuns served in the Sandinista government, for example, and had sacrificed their lives in El Salvador, part of a “liberation theology” that reclaimed this radical Jesus. While Thatcher and Reagan wore Christianity on their sleeves, The Clash’s stand with the dispossessed was more consistent with Christ’s life and teachings.

Unlike “Armagideon Time” or “Police and Thieves,” however, “The Sound of Sinners” did not seem like heavy message music. Yet clearly the song meant much to Strummer, and its comedic disavowal of messianic pretension sparked his most vulnerable appeal of the evening. The singer dismissed rock stars and their glamour, pointedly including himself in that “nowhere” crowd. His anguished outcry aimed to bridge the chasm between The Clash and its audience and, in so doing, perhaps to mend the similar gap widening within the band’s heart.

Schizophrenia nonetheless remained apparent. After a frantic stretch of blazing rockers—“Police on My Back” (with Jones again on lead vocals), “Brand New Cadillac,” “I Fought the Law,” and “I’m So Bored with the USA,” with Strummer pausing only to spit “Oh so you’re still there?” at the audience—the band segued into the pop love song “Train in Vain,” their first US hit.

Next the band brought the funk of “Magnificent Seven,” spinning its tale of workaday desperation before downshifting into the brilliantly bleak seven-minute epic “Straight to Hell.” The song gained further poignancy from Strummer’s extended rant against drug-addled rock stars. Such, the singer noted, made enough money to get their blood changed when their lifestyle grew too toxic, caring not a whit that they were leading others down a dead-end path—a clear reference to an apocryphal story then circulating about Keith Richards.

Strummer brought his improvising to a close with bitter lines like “Hey, man, let’s just party / while our friends are dying / let’s just party / hey, where’s the party at?” before spitting out the song’s aching final verse. Yet, after this sobering, artful challenge, it was back to the lightweight hit “Should I Stay or Should I Go.”

The shifts were jarring—but then it was over. The band went off the stage, returning for a short encore of “Clampdown.” Strummer once again launched into a tirade, blasting complacency about atomic weapons and nuclear power. The song drifted out across the multitude, moving some, no doubt mystifying others.

The band stepped back, intending to return for a final encore. When organizers moved to preclude that by dismissing the crowd, Vinyl tried to grab the mic. A fracas erupted, with the band in fisticuffs with the festival staff. As this unfolded, an emcee took the microphone and called out derisively, “The Clash has left the building,” echoing the fabled Elvis exit announcement. The show was over.

Likely the festival’s most dynamic set, it was surely the most unsettling. The Clash had flung itself against the wall of rock-biz hypocrisy and audience expectation, while being sure to showcase all its hit singles. In its inimitable fashion, the band simultaneously played the game and sought to burn it down.

It was one of their greatest performances. But if The Clash intended a righteous challenge to “business as usual,” it didn’t necessarily come off this way. To many, their behavior was simple rock star ego, self-servingly couched in revolutionary rhetoric. The Clash’s half-million-dollar fee seemed at odds with its concern for the poor. Why didn’t they donate some of their take? And if they didn’t like the festival, why play in the first place? While the band made noises about returning to California to play a free show, this didn’t stem the criticism.

As The Clash returned home with contradictions worsened and internal divisions unhealed, the crucial UK general election loomed. Thatcher’s popularity had dipped from its post-Falklands high but remained well above where it had been a year earlier. In part, this was due to an economy that was bouncing back in some areas—though not in Britain’s hard-hit north, reeling from industrial closures.

Meanwhile, the Labour Party had splintered. Dissident elements had formed the Social Democratic Party that allied itself with the middle-of-the-road Liberal Party. Thatcher’s opponents could not have done her a bigger favor.

Thatcher got a smaller percentage of the vote than in 1979—dropping from 43.9 percent to 42.4 percent—but thanks to the fractures on the left, the Conservatives swept Parliament. This meant Thatcher now had a vast, veto-proof majority—and a free hand to pass right-wing legislation—even though she had won considerably less than half the overall vote. It was an ominous portent, made worse by the news of rebounding popularity for Reagan, readying his own run for reelection.

Meanwhile, the members of The Clash had gone their separate ways after returning from the US Festival. No one seemed to know what the next step was.

June and then July passed with no movement. As The Baker remembers, “I started calling everyone in an attempt to find out what the next move was, but it seemed like no one knew or no one was talking. No matter who I called—Kosmo, Bernie, Joe, Paul, or Mick—I was met with a resolute, ‘I don’t know,’ or, ‘I haven’t heard from anyone.’ It seemed insane.” A conspiracy of silence had descended over the band, with clandestine meetings being conducted behind closed doors.

The Baker finally got a grudging agreement to restart rehearsals—the essential first step toward writing new songs—but with only limited results: “We set up the backline at Rehearsal Rehearsals and put the kettle on just as we did for previous occasions, but it was like flogging a dead horse. One day Paul would turn up, hang around for a while, and go home. The next day Mick would arrive late, miss Joe, and leave again, and so on. Poor Pete Howard was going out of his mind, having succeeded in getting the chance of a lifetime, only to have it turn out like this. I can’t actually remember a complete rehearsal that August.”

Unbeknown to The Baker, pent-up frustration, stoked by the pressure of mass success, was about to splinter The Clash. Jones was soon to be purged from the band that he, more than anyone save perhaps Rhodes, had built.

“The day Mick was fired, the air was thick with tension,” The Baker recalls. “Bernie came into the studio early, then left. Then he would call: ‘Anyone there yet?’ ‘No.’ Click.” When Strummer and Simonon turned up, nothing was revealed to them, and they went across the road to the pub with Rhodes.

The Baker was told to have Jones come straight over on arrival: “Mick arrived suitably late and I told him they were waiting in the pub. He ruffled his feathers and asked me, ‘What are they all doing in the pub?’ I told him I didn’t know.”

After only about fifteen minutes, Jones came back from the pub and without a word proceeded to put one of his guitars into its case. The Baker: “I was busy doing something on the other side of the room and heard Digby say, ‘Do you want me to take the guitar for you, Mick?’ Then Mick said, ‘They’ve asked me to leave the group!’ Digby interjected, ‘They can’t do that, it’s your group, isn’t it?’ Mick said, ‘They don’t want me in the fucking band anymore!’” Jones then picked up his guitar and left Rehearsal Rehearsals for the last time.

It had been an excruciating choice, and perhaps it was the right one. But The Baker articulates the first reaction of many observers: “What did I think when Mick was kicked out of the band? I thought The Clash was over and done.”

Yet how could The Clash end at the height of its popularity, with a battle of historic proportions looming? Was there a way to rebuild, to reinvent, to right the course and get on with its mission? Strummer, Simonon, Rhodes, and Vinyl were determined to find out.