chapter ten

ain’t diggin’ no grave

Immigrants being evicted from “The Jungle,” October 2016. (Photo by Philippe Huguen/AFP.)

Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

—Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto

As for the future, your task is not to foresee it, but to enable it.

—Antoine de Saint Exupéry

Riot police encircled a restless, angry mass gathered on a cool fall day. Shoving ensued where the lines briefly intersected, as frustration and fear threatened to burst into violence. A new life lay beyond the police line, but raw hope was hardly a match for batons and body armor wielded with military discipline.

It could have been the British miners facing off with police, struggling to save jobs and communities, but it was now thirty years later and two hundred miles to the east of the coalfields where that titanic conflict had decided the course of a nation. This was the new world born of that losing struggle—and others like it—playing out its contradictions at a sprawling shantytown called “the Jungle.”

This makeshift colony of immigrants nestled at the edge of Calais in northwestern France, just across the English Channel where the two countries were now connected by a heavily trafficked tunnel. These people had mostly fled desperate areas of the Middle East and Africa, riven by grinding poverty or devastated by wars that ignited after the disastrous US invasion of Iraq in 2003. Having lived through untold horrors, they now hoped to make their way to a better home.

On this day in October 2016, a sign at the Jungle’s entrance claimed over eight thousand ragged, weary souls lived there—perhaps 1,500 of them children—but no one really knew for sure. What was clear, however, was the determination of French officials to dismantle the camp, to disperse the mass, and, in the process, most likely dash dreams of making it to the United Kingdom, their promised land.

The Jungle had become a flash point for conflicting visions of Europe and the world. Some saw the camp as a festering sore to be lanced, its residents scarcely more than animals, with walls needed across once-open borders. Others saw the Jungle in more human terms, not without danger, but filled also with suffering and aspiration, a prick to the consciences of rich Westerners.

On a concrete overpass just outside the camp, an anonymous yet acclaimed graffiti artist called Banksy offered his take: a life-size stencil of billionaire Steve Jobs, cofounder of Apple, portrayed carrying a small bag of clothing like a refugee in one hand and an original Mac computer in the other.

A statement made the connection: “We’re often led to believe migration is a drain on the country’s resources, but Steve Jobs was the son of a Syrian migrant. Apple is the world’s most profitable company, it pays over $7 billion in taxes—and it only exists because [the US] allowed in a young man from Homs.” Banksy’s words were backed up by money and supplies donated to the camp.

Some well-intentioned souls tried to preserve the artwork behind glass, but such was a pipe dream, as the reclusive street artist knew. Soon enough, even more anonymous hands had made his art their own. The figure of Jobs now formed the I in a huge black and red message: LONDON CALLING.

The scene suggested that if The Clash had ended with a whimper more than a bang thirty years before, its reverberations continued to ripple into the world.

“I know human misery / down in dusty shanties,” Joe Strummer sang in “The Dictator,” mocking inequality and indifference: “But my palace ain’t for you scum.” The song had sought to make the suffering of the “third world” real for “first world” audiences. Now the worlds were merging into one in the Jungle, equidistant from the wealthy European capitals of Paris and London.

Although this rising reality of “one world, not three” was something The Clash had struggled for, this new vista was hardly the stuff of its dreams. Sometimes the Money God seemed ascendant everywhere, with profit forever worth much more than people, who were largely pawns on the chessboard of global finance. “We ain’t gonna be treated like trash,” vowed “We Are The Clash,” but all across the human frontier, millions upon millions of lives were being thrown away.

This was not how it was supposed to be. If The Clash, the miners, the “New Deal” Democratic Party, and so much else had gone to the ground in the hard-fought mid-1980s, the promise of a new world dawning seemed immense. With opponents defeated, Reagan and Thatcher had turned to realize their vision of vast horizons with liberty, economic growth, and prosperity for all.

“The Big Bang” became the name for the explosion of financial deregulation unleashed by Thatcher in 1986. Part of a broader “bonfire of regulations,” it ushered in a new era where the market was allowed free rein, offering myriad profit-making possibilities to the corporate sector and, thus, it was said, to the economy as a whole. While the US savings-and-loan crisis that erupted around the same time—abetted by Reagan’s similar deregulation—suggested danger as well as opportunity, few in power took notice.

By 1986, dark clouds of Rhodes’s legal reprisals against Strummer loomed. The band was all over except for lawyers and accountants clocking billable hours. Freed from touring, recording, and rehearsals, the members mostly retreated to their own corners to contemplate what life held next.

The wreckage was significant, but not without bits of mordant comedy. Sheppard describes an increasingly forlorn Rhodes: “So I started getting woken up every morning by Bernie. The phone in the flat was a pay phone in the hall, and it would ring every morning, I’d be in my fucking pajamas, on the phone with Bernie, half asleep, and him going on about, ‘You shouldn’t be listening to fucking Roland Kirk—you should be fucking out there, and doing this, you know, you’re not happening,’ and all this. At one point I finally said, ‘Bernie, why are you ringing me? Why are you ringing me?’ And he said, ‘Beause there’s no one else.’”

Among the missing was Kosmo Vinyl, who had no stomach for legal contention. The consigliere finally made good on his desire to leave the music business behind. Devastated by the band’s collapse and disgusted with a country he saw falling fully into Thatcher’s grip, Vinyl made a new home in New York City.

Rhodes did manage to gain full ownership of Cut the Crap, among other concessions. But while he was undeterred in his fight for the Clash carcass, others were more reflective. Michael Fayne, for one, defends him: “Bernie paid my bills, and bought me clothes—treated me like a son! So I’ve got a lot of respect for Bernie, in that way, because of the way he treated me.”

Still, Fayne admits, “But I know how he treated some other people,” adding, “Bernie should have just started a whole new band, without Joe, without all those guys—I don’t know why he didn’t do that. I suppose, if you’ve got a cash cow, you want to milk it for as long as you can. I think that’s basically what was going on.”

“We can strike the match / if you spill the gasoline”—draft of a never-produced Idea matchbook cover. (Designed by Eddie King.)

Draft of “We Are The Clash” sleeve for a never-released single. (Designed by Eddie King.)

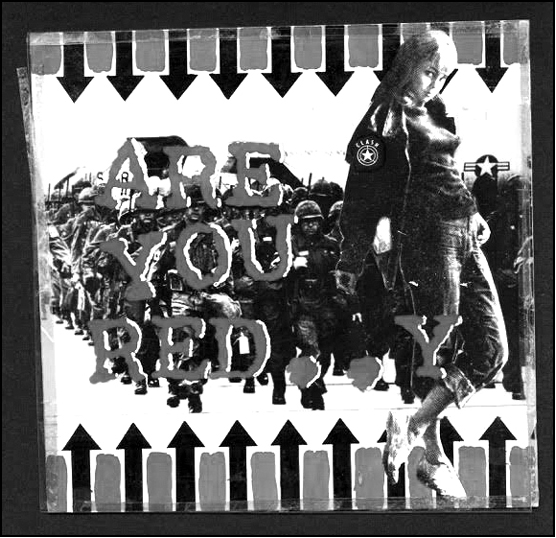

Draft of sleeve for never-released “Are You Red..y” single. (Designed by Julian Balme.)

This is not entirely fair to Rhodes, for his idealism was real, albeit largely untethered to any consideration for others. He was a man who dreamed big, and dreamed of revolution. The Clash was perhaps his greatest dream. Letting go of this band was not easy for the irascible but dedicated manager.

Similarly, White found it difficult to move on, indulging in gratuitous sex and excessive drink after also breaking up with his longtime girlfriend. When he confronted Strummer about his abdications as bandleader, the singer admitted, “It’s all my fault.” But seeing Strummer seeming whipped and broken proved a slender satisfaction. “There was no arguing with Joe, he just agreed with everything you said, even if it was wrong,” White later wrote.

White’s time in The Clash would leave lasting damage, almost as if he had fought in a war, or joined a pernicious cult. This comparison might seem over the top, but the experience was deeply dehumanizing in many ways for the newer members who felt chewed up and spit out. Strummer knew it, later confiding to an interviewer, “I hope we didn’t fuck up their lives too much.”

Like White, Howard carried the scars: “Year upon year, we were being told this, that, and the other by Bernie, and I would go on about the fact that I couldn’t possibly take what he was saying as read. And Joe was saying, ‘It’s like being in the army, you have to . . . Unless we all agree to follow what’s being told, it doesn’t work.’ But, for the exact same reason I wouldn’t have joined the fucking army, I didn’t respond well to that kind of stuff, and I don’t think Vince did either.”

Howard did recognize Rhodes had good intentions, however hard to discern. When the drummer was about to quit midway through the 1984 US tour, the manager actually apologized for the ugly outburst that had caused the standoff, saying: “Look, I’m sorry about the way we talked. I’m trying to arrive at the right idea, but we weren’t getting there. What we’re trying to do is brilliant—it’s big, it’s amazing—and I have to be harsh on you in order to get the best out of you.”

Rhodes’s uncommonly contrite words mollified the drummer who, to his lasting regret, returned to the fold only to face another year and a half of dictatorial chaos. Howard: “We were constantly being battered from side to side on many, many levels: musically, emotionally, sartorially. Every single thing that we did was up for ritual and public annihilation. Not that many people do respond that well to that. Making things difficult for us did not succeed in bringing out the best; it just succeeded in making things difficult for us.”

Yet the trio had persisted. Sighing, Howard explains: “Other than the glamour of the situation, of being in a band everyone knew, the reason why everybody threw themselves face-first into it was because there was a kernel of truth somewhere, buried underneath the negativity, where everybody kind of went, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah—you’re right, that could be it!’ If we just—as Joe had done—exorcised our middle-class demons, and stopped being ‘musos,’ we could actually do something pure, something revolutionary. You did kind of feel like, ‘Okay, if I look hard enough, if I try hard enough, it might be there.’”

This aspiration reflected the band’s staggering ambition, and perhaps it could have been realized. But it could also be a highway to hell. Sheppard seemed to come through better than the others. “Whatever you can say about Bernie, he never let us be pampered rock stars, never let us get comfortable,” Sheppard says. “Of course, he took it too far, but it had some value.”

Howard echoes this: “I think Nick can ride things quite well. And Nick had a far purer punk ethic than any of us did, ’cause he was in the Cortinas and he saw the start of it. Whereas I was listening to fucking prog rock, you know? Now I can see the chaos of any of those things is actually the value of it. That’s the whole fucking point. I can see that now. But at the time, it wasn’t clear.”

Ongoing failures to follow through made it worse. After the break-up, Strummer told White, “I’ll see you’re all right, make sure you’re sorted, get some money . . . you all will,” meaning the three who gave so much only to be jettisoned.

Perhaps Strummer’s low spirits paralyzed him, or maybe the legal chaos created by his untimely departure was too great to make such payments possible. In any case, no money appeared. Soon even the meager wages stopped, and there was one more broken promise to add to the pile.

Ironically, none of the three had signed formal agreements when joining The Clash. So they were not entangled in the legal mess, but also could not pursue compensation for their creative work, and had no rights to anything. By contrast, Rhodes had audaciously claimed songwriting credit equal to Strummer for Cut the Crap.

Howard: “I never had a contract of any description at all. It’s funny, actually. In all of this, the thing that I think I’m most angry and most bitter about is the fact that I didn’t get any money. They got a lot of money, and I didn’t get any.”

While Fayne expresses relief that he personally was never bound to Rhodes by contract, he adds, “I feel a little bit sorry for Pete, Nick, and Vince, in the sense that I think that Joe afterward definitely felt that he should have stood up. He should have fought, you know, that’s what he should have done.”

Howard understood Strummer’s dilemma to a degree: “After getting rid of Mick, Joe relied on Bernie a great deal more . . . which meant he was probably a little bit lost. He made a decision—and one thing Joe did do in life is, if he made a decision, he would go the whole fucking way with it, you know. Whether you’re making the right decision, or the wrong one, it’s just doing it, and living the consequences. And I think that’s what Joe actually did.”

The singer had walked a rough road, but he hadn’t truly seen the neo-Clash experiment through. As White bitterly notes, “At the end, Joe realized he’d made a mistake—but rather than just deal with Bernie, he just got rid of the whole thing. He decided to fold the whole thing, drop everything like a stone, like a hot potato, and denounce it all, rather than take responsibility for what he had pretty much engineered. That was typical of Joe, at that time, in his fashion, to completely run out on everything—and that included me and Nick and Pete and Bernie.”

Strummer found some distraction after the break-up producing an album by the Spanish band 091, but this was hardly smooth sailing either. The singer would soon largely disappear from public view, parenting a second daughter, Lola, while dabbling in acting and film soundtracks. Julian Balme recalls, “In the late eighties I worked in Notting Hill, around the corner from Joe’s house, and I’d often bump into him in the neighborhood. I do remember him being totally, totally lost . . . He’d given it his all but now was running on empty.”

Not all was darkness. Strummer relished his fatherly role in many ways. Freed from road warrior demands, he was able to be more present for his kids. He was also able to visit his beloved Sandinista Nicaragua while making films, and headlined a short, chaotic “Rock Against the Rich” tour sponsored by anarcho-agitators Class War in 1988. But Strummer’s guilt never seemed to lessen.

When one of this book’s authors interviewed Strummer in 1989, the ghosts of the mideighties were still palpable. Asked what advice he’d give musicians just starting out, Strummer’s response hinted at Cut the Crap’s lasting trauma: “Always play the music the way you want to play it rather than the way that somebody you don’t fully know or trust can get in and change it. The better the musician is in control in the music, the better it is going to sound. I’m not saying that nonmusicians can’t contribute—because they can—but [you] can’t trust their judgment all down the line. I’d like the musician to be in control of the music.”

Asked directly about the final version of The Clash, Strummer demurred: “An idea only exists in a framework of time. Like we can say Marcel Duchamp putting out the urinal in an art gallery and saying, ‘This my piece,’ is much better when we consider it was 1917. Completely shocking—we can’t imagine how shocking that was, of its time! Punk rock was of its time. We didn’t really realize in 1984 that an idea drowns like a fish out of water, out of its time. We thought, ‘Let’s do an experiment to find that out . . .’ We didn’t know we would find that out, but I think I found that out, that punk was of its time, and it couldn’t go again.”

Strummer even seemed to welcome this passing, in part for the weight taken from his shoulders: “Now we have rap and other things that are heavy, heavy like ‘Fuck tha Police’ and all that. As far as I’m concerned, I’ve just got to drift off somewhere and try not to annoy people. That’s how I see my role: try to write something good, try to record it good, maybe play it around on stages sometimes, maybe not. Maybe do film sound . . . I just try to keep useful. I don’t see myself as having any influence left, or any message left, really.”

Asked if he hoped his music could still inspire change, Strummer was guarded: “Well, that would be nice, but . . . Life is a funny ride. You go up and you go down. I think both experiences are interesting.”

Strummer dodged when pressed on how The Clash connected to his work now: “I can’t think of an answer to your question. All I know is: I write a song—why, I don’t know. And when I get up on the stage and sing it—why, I don’t know. There is no answer. Why does the sun rise? Why do we get up in the morning? Why do we drive the automobile down the right-hand side of the road? Why don’t we just do a U-turn and drive it up the other side of the road? I don’t know why . . .”

A sense of profound melancholy was impossible to miss. In “Clash City Rockers” Strummer had sung “You got to have a purpose / Or this place is gonna knock you out sooner or later.” In these post-Clash years, one friend described Strummer as “a soldier without an army.” While the absence of The Clash as a source of purpose for him was significant, the challenge likely ran deeper.

Over recent decades, depression has become more recognized as a medical condition, not a personal failing, with treatment options growing. Bruce Springsteen, an artist who was profoundly touched by The Clash, later shared details of his own bouts with darkness. As the New York Times reported, Springsteen “credits medication and the resolve of his wife and bandmate, Patti Scialfa, with being able to survive the onslaught.” Springsteen: “During these periods I can be cruel: I run, I dissemble, I dodge, I weave, I disappear, I return, I rarely apologize, and all the while Patti holds down the fort as I’m trying to burn it down.”

Much of this seems to echo Strummer’s own struggles, which were no doubt worsened by often high-functioning but very real addiction. By the early nineties, the acting out had capsized his marriage with Gaby Salter. Sadly, attitudes and knowledge were more limited at the time, and Strummer was loath to seek help. Nor had the Clash camp been set up to provide such enlightened palliatives.

For some, the sense of an immense opportunity missed is haunting. Fayne: “Joe was tired, really needed help . . . He needed The Clash! Because if he’d had The Clash at the point when all this shit went down, he could have got it all out, in an honest way, and it would have worked. It would probably have been the best Clash album ever, with all those emotions, ’cause you can’t fault Joe for his writing. The problem is if you don’t have the vehicle, you don’t have the vehicle.”

By this, Fayne meant Strummer needed the Jones/Headon Clash. Apparently Strummer felt the same at the end, even telling Antonio Arias of 091 that a “This Is England” couplet—“I got my motorcycle jacket / but I’m walking all the time”—was an oblique comment on the failings of the new band. This needn’t be a slam on those involved, only an admission of a lack of chemistry. Yet a strong case could be made that Strummer did have what he needed, if only he had trusted it.

As these pages show, Strummer’s comrades never threw in the towel—he did. White: “Joe didn’t have enough belief in his own vision. He gave too much credit to Bernie for the success of the band, for creating him as ‘Joe Strummer.’” The singer’s true failing might be that he trusted Rhodes, then lunged for Jones, but didn’t stand by the unit who for two years honorably upheld the Clash banner.

All three have mourned the lack of opportunity to prove their mettle—and, by extension, that of the entire neo-Clash experiment—in the studio. Even Howard, who has tended to be the most dismissive of the unit’s musical accomplishments, admits, “When the five of us were together, there was a certain calm—which was always invaded by Bernie and Kosmo—but if it had been allowed to continue, had been trusted a little more, it could have produced something of lasting worth.”

Sheppard: “Who am I to say what the record would have sounded like? Still, things were definitely getting better [musically]. For example, the interplay between me and Vince continued to develop, to get strong. So if we were left to our own devices, as a group of five people, I think we would have made a record that would have done justice to the songs—and there were some great songs. I think we would have made a good record, yeah. Fuck me, it’s not that difficult!”

Sheppard is quick to admit, “That’s neither here nor there—because that didn’t happen.” Yet if history has any use, it is to provide lessons—and there are lessons aplenty in this ambitious yet failed misadventure.

But as The Clash’s former members sifted the ashes, Reagan and Thatcher pressed their advantage, remaking the world in their image. This was not all bad. In 1986, Reagan defied pressure from the nativist wing of the Republican Party to pass immigration reform, legalizing millions of undocumented migrants, including many driven to the US by his bloody Central American wars.

Growing respect between Gorbachev and the American leader helped end the Cold War, pulling the world back from the abyss. Indeed, the two came close to abolishing their nuclear arsenals at the Reykjavik summit of October 1986. Even though the meeting ended without an agreement—due to Reagan’s insistence on keeping his pet “Star Wars” program—it set the stage for dramatic reductions not only in superpower tensions, but in actual nuclear stockpiles.

Not all went well for the ascendant conservatives. Reagan’s “Iran-contra” gamble crashed on October 5, 1986, when a plane running arms to the contras was shot down. CIA employee Eugene Hasenfus survived but was captured by the Sandinistas. Princeton University history professor Julian Zelizer recounts, “The scandal was enormous, resulting in Reagan suffering the worst fall in approval ratings since those numbers were tracked, leaving the White House paralyzed, struggling to survive.”

Unknown artist weighs in on Iran-Contra scandal and Reagan legacy, 1987.

By rights, this should have brought down the administration. But while high-level officials were convicted in court for their actions, the “Teflon president” walked away unscathed. As Zelizer notes, “Not only did Reagan stay in office—he ended his two-term presidency with a historic breakthrough [by signing] a major arms agreement with the Soviet Union.”

And yet, while Reagan was victorious in many regards, he failed to extinguish either the Sandinistas or El Salvador’s FMLN. The latter fought the US-backed military to a standstill, and ultimately emerged as a powerful electoral force after a peace agreement was signed. El Salvador remained violent and impoverished, however, with a network of savage gangs sprouting from the postwar ruins.

As for the Sandinistas, they lost a 1990 election, but bounced back under the leadership of Daniel Ortega to regain power in the twenty-first century, despite splits in their movement. While their idealism peeled away over time, replaced by growing authoritarianism and corruption, they proved to be far more than a Soviet pawn. If the FSLN did not live up to their initial promises, the same might be said for the Reagan policy that lit the fires of war in the region, but did little to heal the devastation.

Across the ocean, Thatcher would win a third election in 1987, albeit with a reduced percentage of votes and a smaller parliamentary majority. She would fall in 1990, toppled by public outrage over the so-called “poll tax” and a rebellion inside the Tory party. While the grassroots uprising against the poll tax was sweet revenge for many active in the miners’ strike, the Conservatives remained in power, with Thatcherite rule fully entrenched by then.

As for the miners, Arthur Scargill’s prophecy turned out to be true: the industry was square in the Tory bull’s-eye. Relentless rounds of pit closures were followed by privatization. The decline was abetted by competition from cheap imported coal and other power sources. By the end of the 1990s, only 13,000 remained of a work force that had been over 200,000 before the strike. While some heralded this as a victory for efficiency, the pain it caused for workers was horrific.

While Thatcher remained unrepentant, some of her henchmen later admitted to regrets. In 2009, Norman Tebbit, secretary of trade and industry during the strike, acknowledged, “Many of these communities were completely devastated, with people out of work turning to drugs . . . because all the jobs had gone. This led to a breakdown in these communities with families breaking up and youths going out of control. The scale of the closures went too far.”

Time revealed the righteousness of the strike in other ways as well. A steady drip of revelations unmasked the Tory lies: proof of a closure hit list, of Thatcher’s direction of the dissident miners’ antistrike effort, of brutality, espionage, and deceit from the state forces, seen especially in falsified police statements whose discovery led to the dismissal of all charges for those arrested at Orgreave. Such news stoked old furies, but could not change the course already set.

That path was solidly to the right. Both Labour and the Democrats would return to power in the 1990s, in the form of Tony Blair and Bill Clinton, but much had been surrendered to facilitate this revival. When asked in her waning years what she considered her greatest achievement, Thatcher replied, “Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.” By this, she was noting the obvious: Blair—who Joe Strummer came to revile as “Tony Baloney”—won his office by remaking socialist Labour into a kinder, gentler Thatcherism.

Similarly, Reagan’s crowning victory might be seen in the rise of Clinton and other Democrats who advanced the conservative agenda in ways the happy warrior never could have. Reagan had demonized “welfare queens” supposedly living high off the public dole, a racist trope that was effective at splitting working-class whites from the Democratic coalition. But it was Clinton who “ended welfare as we know it” through “welfare reform.”

So too with the self-destructive “War on Drugs.” According to the Drug Policy Alliance, “The presidency of Ronald Reagan marked the start of a long period of skyrocketing rates of incarceration, largely thanks to his unprecedented expansion of the drug war.” The New York Times reported, “During the Reagan years, drug use was also increasingly stigmatized, making the subsidizing of treatment more difficult politically, and the prison population soared as harsher penalties were imposed for use, possession, and sale of illegal drugs.”

For those who viewed drug abuse as a crisis that required public health intervention, not criminalization, these results were disheartening. Clinton once again sought to beat the Republicans by co-opting their “law and order” agenda. By the time Clinton left office, the US prison population was continuing on its way to over two million, nearly five times what it had been at the dawn of the Reagan era.

Perhaps the biggest surrender was the way Clinton Democrats cozied up to Wall Street and big business through “free trade” deals and financial deregulation, including the destruction of the Depression-era Glass-Steagall Act separating the investment and consumer banking industries. These changes were intended to unleash economic energies, and they surely did. But only some benefited.

As this “neoliberal” vision surged, its ideological rival—the “centrally planned” economies of the Eastern Bloc—dissolved, beginning with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Although the demise of the Soviet Union was surely a step forward for freedom and genuine socialism—which would be political democracy made real by economic democracy, not a corrupt “dictatorship of the party”—it also supported an emerging narrative of capitalism’s inevitable triumph.

“There is no alternative,” Margaret Thatcher had often said, and more and more people seemed to agree. One optimistic analyst, Francis Fukuyama, dared to suggest in 1989 that “what we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Fukuyama was hardly the first to entertain an “end of history”—he cited Karl Marx as the idea’s “best-known propagator”—but his was a capitalist version of the vision. “Modern conservatism is entirely about the effort to turn selfishness into the great human virtue,” economist John Kenneth Galbraith had once argued. Reagan and Thatcher had done a pretty good job selling the notion.

“Greed is good,” proclaimed wheeler-dealer Gordon Gecko in the 1987 film Wall Street, capturing the zeitgeist. Reagan’s “trickle-down” economics went global; the unfettered pursuit of profits for a few would ultimately benefit all via the market’s magic, its greater efficiency and innovation. This was not entirely untrue. Mountains of money resulted, but the bounty was not shared equitably. As Vinyl wryly noted, “‘Trickle-down’ turned out to mean them pissing on us!”

One of the most conspicuous symbols of this was the explosion of the housing market, manifest especially in the gentrification of once-blighted inner-city urban areas. Even hardscrabble neighborhoods like Brixton and the South Bronx were not immune as untold wealth moved into real-estate speculation.

The division between those who benefited and those displaced was stark. As a select few grew astronomically wealthy, the many remained stuck. While elected leaders could have tried to level the field a bit, this seldom happened. The political system was increasingly captured by the power of concentrated money.

Like many others who came of age in the punk era, Peter Howard laments what three decades of an unfettered “free market” approach has done to a London that’s still burning—not with boredom, but with the stench of gentrification and an ever-rising cost of living that effectively rules out a lot of creative risk-taking.

As Howard notes, without squatting—a practice that temporarily lifted the pressures of paying rent—he would never have shed his home city of Bath to pursue his dream. Such leaps of faith are more daunting with astronomical rents and so many people working longer and harder, for less and less money.

The resulting cultural void morphs into an emptier vision, one driven solely by the brute logic of survival. “If you can’t afford to live in London, you don’t come here. I mean, if you were in Notting Hill in 1977, everyone you saw was fucking amazing,” Howard asserts. “They had a dress code, or a musical thing they were pursuing, they were in bands. People can’t afford do that anymore. There is no ‘other’ thing that they think is worth pursuing [beyond money].”

If the “free market” was ascendant, and socialism discredited—for reasons both sound and utterly bogus—capitalism with a human face was hard to find. Barriers between countries fell and institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Bank gained more and more control, making neoliberal policies essentially mandatory. National self-determination seemed quaint. If one country adopted policies that stymied the rich, the money would simply flow to more hospitable environs.

“How does a nation—the largest democratic unit the West can claim—exercise its will in a world where capital can roam free and traders can undermine the will of the people by simply shifting resources to countries where labor is cheaper and unions are weaker?” asked Nation writer Gary Younge. The question was inescapable, but no answer was obvious. This reality fueled a global race to the bottom on wages, working conditions, and environmental practices.

Far from upholding tradition, the “free market” was generating change at a shockingly unprecedented pace. Was Margaret Thatcher a punk rocker as conservative analyst Niall Ferguson had waggishly asserted? If punks had sometimes celebrated chaos and their forebears, the Situationists, had wanted a “revolution of everyday life,” the free market brought it in spades.

The untrammeled pursuit of profit enabled by computer-age technology was corrosive in so many different ways. Marx and Engels had foreseen this in The Communist Manifesto, arguing, “Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify.”

This constant swirl of change brought vast moneymaking opportunities, but it could also unsettle human society to a frightening degree. The poetry of lines like “all that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned” should not distract from the agony that was implied, the loss of meaning and direction for lives now adrift in an ever-shifting commodity stream.

For Marx and Engels, this dislocation would strip away illusions, enlightening in the most concrete, hopeful sense—the development of class consciousness that would shred the false promises of capitalism: “Man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.” While the full accuracy of this optimistic interpretation remained to be seen, some element of truth was present. This never-ending disruption, mixed with the growing inequities, was bound to generate a potent backlash.

In part, this was seen in the ascent of Islamic fundamentalism. Terrorist groups such as al Qaeda and, later, the Islamic State fed off the pain generated by the West’s economic, cultural, and military imperialism. Although most Muslims opposed such entities—and indeed were their main victims—the brutality fed a new narrative. After the 9/11 attacks in New York City, Washington, DC, and Pennsylvania, Islam was seen by many as the enemy in a “clash of civilizations,” replacing vanished Soviet communism.

A more hopeful face of dissent came with the Zapatista uprising in Mexico as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect on New Year’s Day 1994. On November 30, 1999, a motley band of protesters shocked the powers-that-be by shutting down the World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle. This was the first of a series of street confrontations with elite institutions of global capitalism, stretching from Washington, DC, to Quebec City, to Genoa, to Davos, and beyond.

As protest swung back into the headlines with Seattle, Strummer had found his artistic and spiritual footing again with a new band, the Mescaleros. With these compatriots as collaborators, Strummer revived his past fire in songs both new and old. In interviews, he began to resemble the punk rabble-rouser of yore again, if with greater humility and ever-present self-deprecation.

“I’m proud that we have ridiculous aims, because at least then we ain’t gonna underachieve,” Strummer had said amid the neo-Clash fervor of early 1984. The reinvigorated singer may have remained unwilling to reprise such ambition, but he paid homage to those with similarly lofty aims, in particular the DC punk band Fugazi.

Formed in 1986, Fugazi had its roots in “straight edge” progenitor Minor Threat and “Revolution Summer” luminary Rites of Spring. The unit was part of a wave of subterranean bands that rose to stratospheric heights of popularity for the underground. Beginning with Nirvana’s 1991 hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” some of these vindicated Strummer’s 1984 aim of bringing “rebel rock” to the top of the charts, thanks in no small part to MTV and major label backing. Fugazi stood out in its resolutely independent stance, refusing to sign a record deal, make videos, or otherwise accommodate the corporate-rock world.

Strummer had once dismissed such outliers as a “tempest in a teacup.” Having finally escaped his CBS-contract straitjacket, however, the singer had something of a new perspective. He now seemed to recognize that the musically ferocious, clean-living, and politically radical Fugazi—dubbed “America’s Clash” by none other than Sounds—had accomplished much of what he, Simonon, Rhodes, and Vinyl had stretched toward in their failed attempt to reinvent/purify The Clash.

Ironically, The Clash had scored a posthumous #1 UK hit themselves, thanks to the use of “Should I Stay or Should I Go” in a Levi’s advertisement. Strummer was ambivalent about this, but as he had not written the song, he had little say in the matter.

When the subject came up in a 1999 interview, discussion ensued about the ugly intraband legal battle sparked when Dead Kennedys’ lead singer Jello Biafra turned down a similar request for use of their song “Holiday in Cambodia” for a commercial. When an interviewer suggested that Biafra didn’t accept the offer simply because the price wasn’t high enough, Strummer wryly noted, “They always said that, didn’t they? Everybody’s got their price . . . But what about Fugazi?”

This was no idle query. Acclaimed punk/hip-hop photographer Glen Friedman recounts a head-turning Fugazi anecdote: “I witnessed the legendary music mogul Ahmet Ertegun coming backstage to try to get this ‘unsignable’ band to sign with him. He offered them ‘anything you want’ and said, ‘The last time I did this was when I offered the Rolling Stones their own record label and $10 million.’ Fugazi politely declined and [band cofounder] Ian MacKaye then changed the subject and continued to talk about their shared love of [the music of] Washington, DC.”

Such tales led Strummer to remark, “Ian’s the only one who ever did the punk thing right from day one and followed through on it all the way.” When the singer returned to DC in 1999 for his first show there in a decade, he paid tribute to Fugazi during a fiery new song, “Diggin’ the New.” In a SPIN interview in 2000, he singled out Fugazi as embodying “the true spirit of punk”—a compliment MacKaye later returned, referencing the audacious busking tour of 1985.

Twinges of Strummer’s regret over the fall of the neo-Clash experiment can be detected here. Still, nobility can be found in defeat as well as in triumph. If the last version of The Clash, like the band as a whole, failed to accomplish their lofty aims, the effort was hardly in vain.

Sadly, Strummer never seemed to stop apologizing for that time, even once going so far as to say, “We never played a good gig after Topper left.”

This was silly and insulting. White called Strummer “an asshole” for the remark, then made his broader case: “Joe kind of artfully manipulated The Clash II period in his subsequent interviews as to say it was all just a big mistake—but clearly it wasn’t, ’cause it was two years of touring, you know?” Yet while Strummer admitted to liking “This Is England” and the busking tour, the overall sense he left was one of embarrassment, especially over the firing of Jones.

Rhodes offers no apologies, while resisting revisiting the time in any depth. In 2013, he told this book’s authors, “A few years ago I was approached by publishers to do a book giving my side of the story, but I had no time . . . Though the past is quite important to me, the future is where my thoughts are most active.” (Ironically, a Rhodes memoir is now slated for release in the fall of 2018.)

Nonetheless, Rhodes’s anger and pain is evident: “To sum up: I had an idea for a great, creative, and politically radical rock group. Found the people, got the thing moving, success arrived, parasites moved in and drugged the musicians with bullshit, etc., in the process gradually erasing our close friendship. My role with the group—particularly Joe—became ‘I take the blame, they get the credit.’”

Although Rhodes may have a point here, he is not above his own historical revisionism, claiming, for example, “It was [Joe’s] idea to have a drum machine on Cut the Crap and of course I had to deal with it.”

The manager is on firmer ground in arguing, “Fact is, the album works good, the artwork is cool, and ‘This Is England’ still inspires.” Rhodes’s website contains a couple of dozen fan reviews of Cut the Crap that share this more upbeat view, defending the record as “unjustly neglected,” “a solid punk masterpiece,” and “an all-out return to the punk ethic the band had been straying from.” The headline of another section of the website reads, “Popular Thieves and Unknown Originators.” It is clear in which category Rhodes sees himself, and not without some justification.

Intriguingly, Rhodes’s old ally Simonon defended Cut the Crap’s exclusion from the Sound System box set, saying, “It’s not really a Clash album,” due to the absence of Jones and Headon. Yet overall, the bassist has been far less apologetic about the era than Strummer, in one interview reaffirming directly to Jones, “We were right to fire you.” While Simonon has belatedly criticized Rhodes’s role, he nonetheless insists that the final Clash “had some really good songs.”

This seems more accurate than Strummer’s dismissals. Michael Fayne recalls that time as “a baptism by fire,” but says, “Something good came out of that. Without that experience, where would I be?” For him, the band’s mix was too combustible, the aims too impossibly high, but all the more glorious: “The Clash were always gonna fail, if you look at the initial ingredients and characters. They were always gonna fail, that was inevitable. But, man, what a way to go out!”

Describing the distance between The Clash’s rhetoric and its reality as “Grand Canyon wide,” White remains skeptical about its impact in any form: “Thanks to the music, you could feel better about yourself . . . But if you took on that revolution, in any meaningful sense, [music] is more like a kind of steam valve, you know, where people let off steam. It’s arguable whether it’s actually getting people to accept the system itself, by being able to listen to loud punk rock music, rather than get out and destroy some of the shit.”

Even White can’t mask his pride in the band’s power, however: “A lot of people saw The Clash Mark II and got a lot from it, were influenced by it, in a positive way . . . You can’t deny it.” While disgusted by the hypocrisy, when pressed, the guitarist grants that The Clash might have been “a lie that told the truth.”

Howard has a similar take: “Beyond all the breakdowns, Joe had a pure intent, and I think he believed Bernie had those pure intentions as well. The politic of the band was important, just saying, ‘What the fuck are you doing? What are you doing here? Why are you enjoying this, in this way? It isn’t about that. Think about this.’ To be able to plant a seed of ‘just think’ is fucking amazing, incredibly potent.”

This was by no means easy. Howard: “Joe wanted to say, ‘Just think,’ to a bigger audience, which is a bit of a conundrum, because you’re doing something that relies on communicating with a small audience. Joe was genuinely agonizing about this, going, ‘Look, it must be possible to do something good to a big audience. Why isn’t it possible? It doesn’t have to be shit. Come on, let’s do it.’”

While the drummer’s bitterness is apparent, so is a respect that can supersede the pain: “I have pondered it for many, many years, and I think that fundamentally pure intent was the reason why we all committed ourselves so much to it, were so affected by it, almost incapable of just walking away from it.”

Though Howard asserts, “It went on far longer than it should have,” nonetheless “there was something of importance, a real potential. It failed—but having said that, I can’t think of a single thing, at the moment in music, that’s even attempting this, that would even have part of that conscience. I can’t think of anything.”

Of the three “new boys,” Sheppard views it all the most philosophically, with flashes of easy self-deprecation: “What’s interesting about that whole thing is that The Clash is important culturally—far more important than bands that sold a lot more records. If you actually analyze what The Clash did, it’s very little, in concrete terms. I mean, they didn’t introduce a bill for gun control, or try and get a ‘health care for all’ program through. We’re talking about a pop group, you know, who took drugs, and played songs, and drunk a lot, a bunch of guys, troubadours, wandering the world singing their songs. It’s a phenomenon, you know? Maybe, for our generation, The Clash was the band that mattered.”

Sheppard sometimes speaks of The Clash in the third person—as if he hadn’t been in it for two years—but pride shines through: “It’s ancient history now, in human terms, but it moved people, made a lot of them look at themselves, at their lives, enabled them to do something that they maybe wouldn’t have done if they hadn’t heard it, which is very interesting, quite surprising. The lyrics obviously touched people, and enabled people, but I think so did the music. [The Clash’s] gift was purely about somehow releasing something in other people.”

Howard, White, and Sheppard all regard the busking tour as the most powerful validation of the neo-Clash experiment, but for the last of the three, there was a special significance: “When we were in York, we met a couple of wonderful, hilarious guys who were miners—or had been miners—one of whom was called Spartacus, because his dad had seen the film the night before he was born!”

The memory brings a smile to Sheppard’s face as he continues: “And he was a fucking riot, hilarious—he was like the Johnny Cash song ‘A Boy Named Sue.’ Imagine growing up in a mining village being called Spartacus! These guys are tough, man. These guys don’t take any prisoners. They’re fucking . . . they’re miners, for fuck’s sake. And he’s called Spartacus, you know? And we’re in York, sitting around in the kitchen of somebody’s house, after a bunch of busking gigs, and we’ve had a few beers. These two guys were like a duo of comedians, just had this fantastic, surreal play off each other—they had us in stitches.”

Not all was for fun, however: “In the middle of it, Spartacus turned around and said, ‘In that whole period, you know, when we were on strike, and it was really bleak, it was winter, it was fucked . . . We had no money, we had nothing, the one thing we had to keep us warm were those two nights in Brixton, when we came down and watched The Clash.’ They were big fans, obviously—that’s why they were there—and they said, ‘That gave us real warmth, and comfort, and hope.’”

His voice thickening with feeling, Sheppard brings the story around: “And I thought, ‘Well, fuck, you know—that’s vindicated the whole time I’ve spent in this band, and that one thing, that’s enough. I don’t care what the NME thinks of my time in the band. I don’t care what anybody thinks of my time in the band—because if I’ve done that, that’s enough, you know? To me, that’ll do.”

Many argue that Sheppard’s Clash was not the genuine article, that no unit without Jones or Headon could be. Yet this is hard to sustain. Was the Chimes version not real, the first album not The Clash? Was it not The Clash playing on the Anarchy Tour, or at the US Festival? If the final Clash played with fire and creativity, touched its audiences, inspired them, does this not matter?

Ultimately, Sheppard makes a convincing case. A similarly passionate Vinyl seconds the emotion: “Okay, Thatcher won—but at least we put up a fight, right? At least we said, ‘No, we ain’t going along with this, no fucking way.’ Like the miners, we tried to do something, even if it weren’t enough in the end.”

A fuller sense of the importance of these lost battles of 1984–85 became clear on a single shocking day more than twenty years later. On September 29, 2008, the world economy nearly melted down, with feverish profit-seeking collapsing into a near-catastrophic downward spiral across global markets.

While the chain of events that caused the stock market nosedive and subsequent world recession—the worst since the 1930s’ Great Depression—are complex, the crisis represented the fruit of the Reagan/Thatcher era as clearly as a devastating flood follows a massive rain. British journalist Seamus Milne later wrote, “A generation on, it is clear that the miners’ strike was more than a defense of jobs and communities. It was a challenge to the destructive market- and corporate-driven reconstruction of the economy that gave us the crash of 2008.”

Capitalism had not resolved its potentially fatal internal contradictions nor answered the questions of equitable distribution, democracy, or sustainability. Milne’s words ring with truth: “The vindication of the miners’ stand is well understood thirty years later . . . [Their defeat] brought us to where we are today: the deregulated, outsourced zero-hours modern world.”

The crushing of the strike cleared the way for this resurgent capitalism at just the wrong time for the world’s environment, as best-selling author Naomi Klein has pointed out. Global warming emerged into broad consciousness shortly after the events described in this book. In fact, as the New York Times has reported, “The recognition that human activity is influencing the climate developed slowly, but a scientific consensus can be traced to a conference in southern Austria in October 1985”—even as the poststrike lament, “This Is England,” was falling off the charts.

For Klein, this climate crisis is less about carbon, as such, and more about capitalism. The British miners’ strike might be seen, ironically enough, as a failed bulwark for the environment against what Klein derisively calls the “market fundamentalism” preached by the Reagan/Thatcher regimes.

This is so, even though many on the left now regard coal mining itself as a brutal relic of the past. Such attitudes are understandable. But while the danger of the work—and coal’s contribution to eco-catastrophe—is undeniable, nothing that exists today would have been possible without the toil of untold miners over the past two centuries. This sacrifice can never rightly be forgotten, in moral terms, nor can the political import of the NUM’s desperate last stand.

Is our society’s top priority the protection of people, of all life on earth—or is it profit for the few? For Klein, the trajectory since 1985 is clear: “The past thirty years have been a steady process of getting less and less in the public sphere. This is all defended in the name of austerity, balanced budgets, increased efficiency, fostering economic growth. Market fundamentalism has, from the very first moments, systematically sabotaged our collective response to climate change, a threat that came knocking just as this ideology was reaching its zenith.”

Like climate change, the 2008 economic crisis made one thing, at least, obvious: history has not ended. Although swift action by elite policymakers helped avert the worst possible consequences of the meltdown, the curtain had fallen on one era, and a new drama began to unfold, offering profoundly uncertain outcomes.

In America, hope was fueled by the election of the nation’s first black president, Barack Obama, at the head of a vibrant multicultural coalition, followed by the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011 and the insurgent 2016 presidential campaign of democratic socialist Bernie Sanders. Economic inequality was back on center stage, and socialism no longer seemed a dirty word. Between the cracks in capitalism’s seemingly immaculate veneer and the withering of authoritarian pseudosocialism, broader political horizons again seemed possible.

Darker forces, however, were also unleashed. The rise of Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News as the source of a right-wing “alternative reality” seemed the logical culmination of the reactionary power of the tabloid assault on the miners. This media powerhouse helped foster the Tea Party movement in America, which took Reagan’s antigovernment rhetoric to new depths of fanaticism.

In the ensuing chaos, an egomaniacal billionaire con man was able to ride the surge of desperation and disillusion into the White House. Donald Trump revived Reagan’s “Make America Great Again” slogan and the “law and order” mantra of Nixon. Benefitting from a covert Russian hacking campaign, he coarsely summoned the ugliest bits of America—racism, misogyny, anti-immigrant/anti-Muslim bigotry, greed, and more—to build a movement that narrowly won the electoral college, though not the popular vote.

Trump is surely disgusting as a person—“morally bankrupt and pathologically dishonest,” in the words of the Washington Post editorial board—yet he has a certain malevolent genius. While Trump is hardly “a champion of the forgotten millions” as one commentator claimed, he did speak to a very real pain.

Bitter fruit whose roots stretch back to 1984–85.

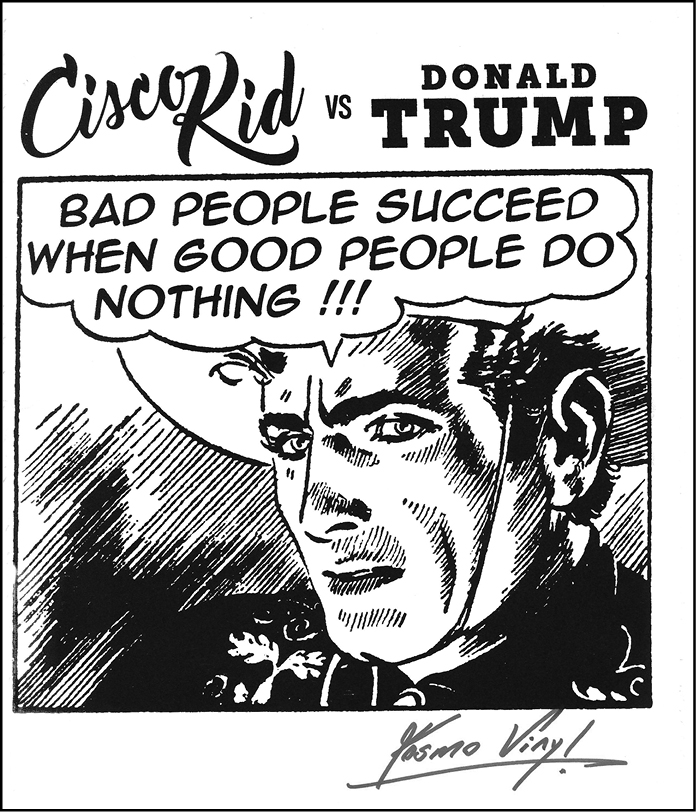

Kosmo Vinyl resurrected the spirit of The Clash with a fiery “Cisco Kid” art series opposing Donald Trump.

When factories and mines closed, dreams died with them, and lives turned to self-destruction. For the first time in modern history, life expectancy actually began to fall for America’s white working class. In 1984, Joe Strummer blamed Reagan’s rise on the drug culture; in 2016, blue-collar areas suffering an epidemic of opiate addiction voted disproportionately for Trump.

As the New York Times wrote, 2016 “brought to the surface the despair and rage of poor and middle-class Americans who say their government has done little to ease the burdens that recession, technological change, foreign competition, and war have heaped on their families.”

Earlier that same year, British politics were rocked by the triumph of “Brexit,” when UK voters narrowly chose to leave the European Union. Although this move promised to severely injure the country’s economy, it was sold as a reassertion of national sovereignty eroded by economic change and immigration.

The pain that helped birth both President Trump and Brexit can be traced right back to Reagan and Thatcher, together with erstwhile opponents who shifted rightward for political expediency. Trump scratched out his win with the help of the Rust Belt, where working-class voters deserted the Democratic ticket. The margin was slender—some forty thousand votes switched in three states would have reversed the verdict—but sad and scary nonetheless.

Similarly, Brexit triumphed thanks to defecting Labour voters in England’s north, including depressed coal-mining areas like Newcastle, Sunderland, and Stoke-on-Trent. If Brexit, like Trump, was powered by anti-immigrant animus, it also reflected class desperation. As the Nation’s London correspondent D.D. Guttenplan noted, “The losers in globalization’s race to the bottom [used] the only weapon they had to strike at a system that offered them nothing.”

“The god that failed” here was the “free market” deified by Reagan and Thatcher. Yet a left now seen as drifting away from class struggle did not benefit. New York Times columnist Eduardo Porter has noted how the market-fundamentalist gospel was “brought down by right-wing populists riding the anger of a working class that has been cast aside in the globalized economy that the two leaders trumpeted forty years ago.” The rise of this aggressive far right inevitably evoked the specter of Europe’s fascist past.

For Vinyl, the moment seemed frighteningly familiar. The aging agitator returned to the fray, fashioning his art into a weapon. Working relentlessly, Vinyl spat out a series of neo-Situationist “Cisco Kid vs. Donald Trump” broadsides in the months before the US election, all to no avail. Vinyl: “The morning after Trump won, I had the same feeling of utter defeat as after the miners were beaten and The Clash had broken up—just sick to my soul.”

Vinyl was not alone in his darkness. As Trump and his administration touted “alternative facts,” George Orwell’s 1984 shot to the top of the New York Times best-seller list. Global tensions that had receded after the end of the Cold War reignited, stoked by what the New York Times described as Trump’s “chilling language that evoked the horror of a nuclear exchange” in threatening North Korea with “fire and fury like the world has never seen.” As a result of the president’s bellicose rhetoric—along with the looming threat posed by climate change—the hands of the Doomsday Clock were moved to two minutes before midnight in January 2018, even closer than in the fear-drenched days of 1984. Meanwhile, Muslims faced attacks and immigrants endured a renewed wave of deportations, with all bracing for far worse perhaps yet to come.

This moment was pregnant with danger. But possibility also glimmered. The massive protests that greeted President Trump, the raucous town hall meetings fighting to preserve health care, the surprising Labour surge led by Jeremy Corbyn, the outcry after the terrible Grenfell Tower fire, born of the Thatcherite “bonfire of regulations”—all suggested what Vinyl already knew from his Clash years: the future remains up for grabs, the final tale is not yet written.

At The Clash’s second-to-last show ever in July 1985, the mouthy firebrand had roared, “This here rhythm ain’t never gonna stop—it’s gonna rock you to the front till the very last drop!” Later, he worried that the words might seem pretentious. In fact, they not only evoke the irrepressible spirit that made The Clash a band that touched lives deeply and indelibly, but also carry meanings that still resonate.

Vinyl was talking about the power of art and audience, how this communion could generate an energy that was particularly powerful at the stage front, the nexus between band and crowd. The word “front,” however, also echoes The Clash’s martial metaphors. The extraordinary force that pulled one into the vortex of performance could also push outward, propelling the listener onto a battlefield, to the front line where human need cries out for defenders.

Joe Strummer’s old namesake Woody Guthrie evoked a similar concept:

Wherever little children are hungry and cry,

Wherever people ain’t free.

Wherever men are fightin’ for their rights,

That’s where I’m a-gonna be . . .

No human being has the strength to take that stand every day, with untiring consistency. Strummer’s foibles described herein recall Phil Ochs’s famous disclaimer, “I could never be as moral as my songs.” Still, while knowing that words—including his own—could often be all too cheap, Strummer refused to surrender, continuing to believe that time can march with charging feet.

In mid-1982, as the centrifugal forces that would rend and reassemble The Clash gathered, Strummer told Mikal Gilmore, “I’ll tell you what real rebellion is: It’s something more personal. It’s not giving up. Rebellion is deciding to push ahead with it all for one more day. That’s the toughest test of revolt—keeping yourself alive—as well as the cause . . . It’s the only rebellion that counts: not giving up.”

This was a simple yet critical insight. Vinyl recalls how Strummer kept a NUM button on his leather jacket for years after the band’s end: “When I asked about it, Joe told me, ‘A miner gave it to me—how heavy is that? It doesn’t get any heavier!’” If this was a tip of the hat to the “never say die” miners, Strummer also knew that wearing badges was not enough, that action spoke loudest.

His best tribute to that lost struggle came when Strummer mounted the stage in support of striking firefighters only a few weeks before his untimely death in December 2002. Mick Jones was in the audience. During the encore, Jones spontaneously joined his old partner for three songs, including “White Riot,” the anthem they had come to blows over during the long run-up to their final fracture.

Fate brought the pair together onstage one more time, not on a lucrative reunion tour, or for suits holding big-money tickets at a Hall of Fame soiree, but for striking workers, fighting the harsh winds of post-Thatcher austerity. That night, the best spirit of The Clash lived again, if only for a few moments—just as it can any time, anywhere that human creativity, determination, and compassion rise.

If the band “The Clash” is gone forever, such an idea of “The Clash” can be with us always. “Ideas matter,” the biblical scholar Marcus Borg has written, “much more than we commonly think they do, especially our worldviews and values, our ideas about what is real and how we are to live. We receive such ideas from our culture as we grow up, and unless we examine them, we will not be free, but simply live out the agenda of our socialization.”

Borg’s point that our sense of what is possible is often constrained by our society could have come from Joe Strummer himself. In 1984, the Clash frontman insisted, “Money doesn’t get us anywhere. I’m talking about preventing the world from going backward, finding a decent economic order where the poor are taken care of and everyone gets an even break. I’m talking about getting the world round to that kind of sanity, which is chiefly what we’re trying to do in The Clash.”

Realism met determination in the singer’s words, and the call to action was clear: “We ain’t just some shitty rock band trying to fake our way through. We are really trying to make a difference. People ask me, ‘Can The Clash change anything?’ Of course we can’t. But we can be a chink in the blinds.”

This last point is crucial. Strummer strained to write songs of deep worth, to perform them with fervent passion. But he knew that it took an audience to make them truly live, not just in ecstatic moments, but in changed lives, in new consciousness, in action. Strummer was trying, in the best punk fashion, to point the listeners away from the “stars” onstage and back toward to their own power, their responsibility to be participants, not just spectators.

A quiet reminder of this challenge can be found lurking in the pages of Sound System’s “Service Manual”: the words “It’s up to you” written in ten languages, signaling a global intent. This simple phrase recalls Strummer’s insistence from a Brixton stage, standing with the striking miners, that “The Clash” meant not simply the five members of the band, but everyone in their audience.

This audacious idea, of course, is only as true as anyone makes it, with blood, sweat, toil, and tears. But to act, one first has to believe, past jarring reverses, even seeming defeat, that, somehow, some way, a better world is possible.

“As for the future, your task is not to foresee it, but to enable it.” In sacrificing his life in a world war against fascism, Antoine de Saint Exupéry honored this vow, inspiring others to act on life rather than accept it as is. This “enabling” of the future is the gift Sheppard spoke of, the “chink in the blinds” Strummer conjured night after night onstage, giving the best of himself in the process.

This is the rhythm that ain’t never gonna stop, the radical claim Strummer staked in “North and South.” As a bleak Christmas approached for tens of thousands of strikers, as the lifeblood of their embattled families and communities oozed into the earth, The Clash spat out words of hope and defiance: “We ain’t diggin’ no grave / We’re diggin’ a foundation / for a future to be made.”

Tens of thousands of lives were touched by such Clash nights in 1984–85, even if subsequent dismissals or revisionism have sought to erase this inconvenient truth. Small, persistent pushbacks have grown, however. Visitors to Duke’s Bar in Glasgow, for example, now walk past a small round plaque commemorating The Clash’s busking show there—a lifetime ago, on May 16, 1985, before the forces of “market fundamentalism” overtook the lives of those who witnessed it.

This all might seem to be dead, dusty history, of little use beyond nostalgia. Yet while the energy of such an experience, in all its ragged, one-off glory, can be tamped down for a period, it can never be completely controlled. Nor, perhaps, can the participants feel compelled to simply settle for less, ever again.

If the last stand of The Clash has elements of tragedy and farce, it is more nearly defined by such sparks of persistence and passion, squeezed out over two years of striving. That time was dedicated imperfectly but powerfully to an idea of how the band might be purified and reinvented to the point where boundaries between fan and performer dissolved, and vast windows of possibility opened.

We are the clash—we are the rub between what is and what can be, between reality and possibility, the arena where truth can bring transformation. And, as Joe Strummer knew, truth often means descending into the house of suffering.

In many ways, this book has been a journey to that place of pain. It has no tale of unvarnished triumph to share. It can hope, however, to carry the ring of truth, of hard-fought battles, stinging defeats, and saving lessons learned. Above all, it seeks to faithfully transmit the restless, contradictory, fully human spirit of the band it celebrates, critiques, and tries to resurrect, in however limited a fashion.

Those now reading this book might be seen as part of the only Clash alive in flesh and blood. If so, take these words as a call to battle. Win or lose, we must spend ourselves again and again on those barricades, in a thousand ways large and small. Anything less is not worthy of The Clash, this band that truly mattered.

“When I say. ‘We are The Clash,’ I mean WE . . .” Joe Strummer in Hip Hop Punk Rock T-shirt with Clash fans at Chicago’s Sears Tower, May 1984. (Photo by Eddie King.)