chapter five

out of control

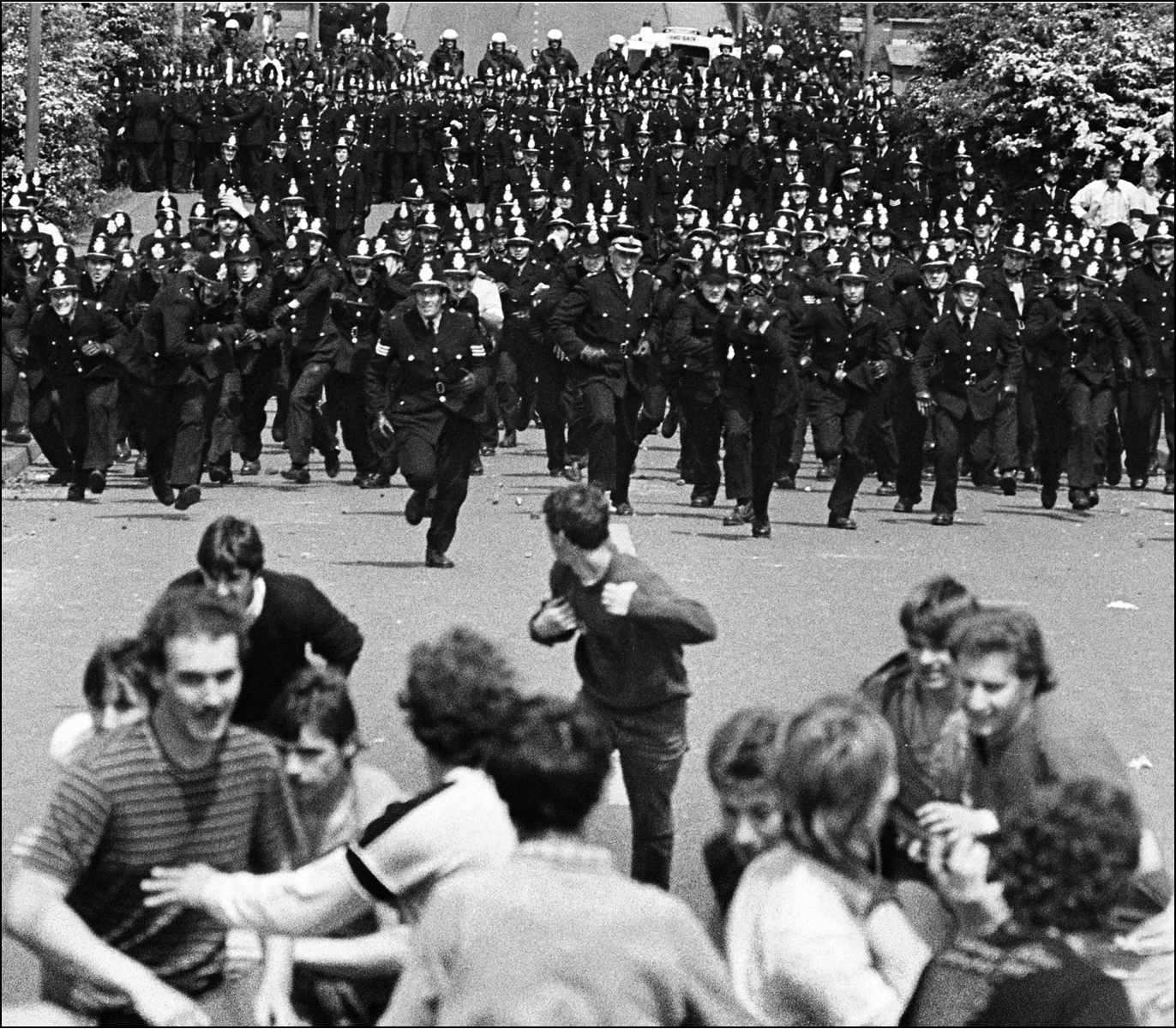

Police charge miners at Orgreave, June 18, 1984. (Photo © John Sturrock/reportdigital.co.uk.)

We had to fight the enemy without in the Falklands. We always have to be aware of the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty.

—Margaret Thatcher, July 19, 1984

Either the human being must suffer and struggle as the price of a more searching vision, or his gaze must be shallow and without intellectual revelation.

—Thomas de Quincey, 1845

The riot shield came down hard, with a sickening crunch. Hit from behind, Arthur Scargill pitched face-first to the ground, knocked senseless.

It was barely past eleven a.m. on Monday, June 18, 1984. Chaos swirled around the unconscious union leader as riot police and mounted officers assaulted miners picketing the Orgreave coking plant near Sheffield.

The attacks had been coming in waves for two hours. Many miners had taken off their shirts in the morning heat, shedding their only protection against the savagery. Amid what was effectively a police riot, an impartial observer might have been forgiven for thinking that George Orwell’s 1984 was coming to pass.

NUM member Arthur Wakefield witnessed the unprovoked assault on Scargill. Ironically, it came mere moments after the union president had rebuked some miners who—angered by the earlier attacks—were throwing stones at police lines.

The repeated brutal charges sowed panic in the mostly peaceful ranks of picketers. Wakefield recalled, “The lads were climbing the fence on the opposite banking, some of them falling down, being chased by the police on horses and with dogs . . . The ‘cavalry’ are first as usual, then the riot squad.”

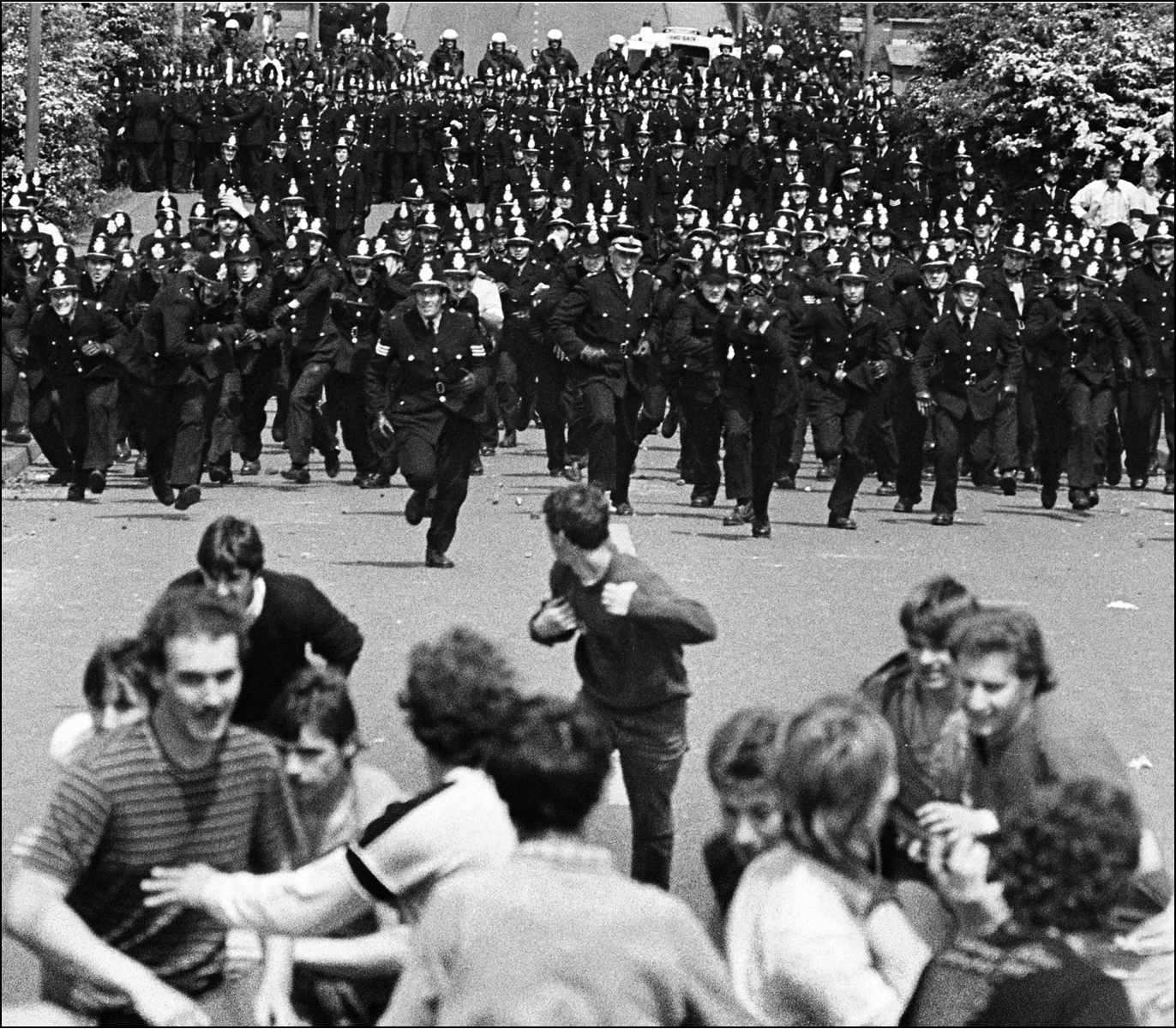

Lesley Boulton, a strike supporter armed only with a camera, was helping a bloodied miner only to be targeted herself by a mounted policeman. John Harris’s camera captured the moment the baton came down. Clash biographer Marcus Gray spoke for many in calling this photo of the officer leaning out to take a full swing at the unarmed female spectator “the most memorable image of the miners’ strike.”

“I felt the truncheon go past me—just missed by the skin of my teeth,” Boulton explained. “The police were actually having a very good time, they were laughing and joking, enjoying this huge exercise of brutal authority . . . You got the sense that they were just out of control, completely carried away.”

Such bare-knuckled displays contrasted with the bland assertions of government white papers: “The traditional approach is to deploy large numbers of officers in ordinary uniforms in the passive containment of a crowd.” The real aim, however, was shared in police tactical manuals: to “incapacitate” the miners.

The Labour Party paper, June 22, 1984—one of the few media outlets to publish this photo. (Photo © John Harris/reportdigital.co.uk.)

The day had dawned with electricity in the air, but little sense of the carnage to come. In the biggest face-off in the now fourteen-week-old strike, perhaps ten thousand miners and supporters stood across from more than five thousand police, including riot squads and mounted officers.

The union had been targeting Orgreave for three weeks, seeking to turn the tide in what was not only the biggest industrial dispute in recent British history, but a true struggle for the country’s future. Previous days had been confrontational, with injuries and arrests, especially on May 29, when the riot squads had made their first appearance. At the time, Scargill argued, “The intimidation and the brutality that has been displayed are something reminiscent of a Latin American state.”

Now the NUM intended to make its stand, shutting down the plant, blocking trucks, and cutting off the supply of coke to the nearby Scunthorpe steelworks. To do this, the union needed massive numbers of picketers to overwhelm police lines. Their call had been answered. As Wakefield recalled, “I’d never seen so many of our lads all together, it brought tears to my eyes.” The police had similarly bolstered their ranks.

This meant a struggle for control at the gates of the plant, one that would begin once trucks were sighted. The strikers didn’t have long to wait. Wakefield: “There was a lot of shouting going on as the lorries went in. It’s eight forty-five a.m., the lads started the chant of ‘Here We Go’ and there was one big push against the police lines”—a literal push by massed miners against a similar clump of government forces. It was turned back, and the first wave of trucks swiftly rolled through.

This contest was commonplace by now, repeated daily over the past three months. Although very physical, it generally followed certain unspoken rules that limited injuries on either side. Today would be different.

While some stones had been thrown from deep in the miners’ ranks earlier, there was little happening when suddenly the lines opened and a phalanx of mounted police emerged with blood in their eyes. Wakefield: “This time the police went berserk and the riot squad charged up the field with the ‘cavalry’ [and] they did something that I had not seen them do before, they turned to where we were standing peacefully picketing and started hitting whoever they came across. I’m thinking, ‘This is it’ . . . I’d never seen anything like it.”

The police even pursued picketers into the nearby village, brutalizing at will. Broken and bloodied, the miners scattered. “The battle kept going on and off until one p.m.,” Wakefield remembered. “It was like ‘Monday, Bloody Monday.’” There were seventy-nine people hurt and ninety-three arrests, including a shaken but unbowed Arthur Scargill, wearing a United Mineworkers of America baseball hat sent as a sign of solidarity from across the ocean.

Seventy-one miners would soon be charged with “riot,” an offense carrying a possible life sentence. If this penalty seemed extreme, given that most had done nothing except be on the receiving end of a truncheon, “The Battle of Orgreave” showed how just far Thatcher was willing to go to defeat the miners.

* * *

Meanwhile, the band whose first single was entitled “White Riot,” whose new songs “This Is England” and “Three Card Trick” warned of batons dishing out bloody “law and order,” and whose singer had just crossed America evoking the unfolding British drama night after night, was doing . . . what exactly?

The Clash had been home for two weeks from its triumphant US tour, the journey intended to solidify the band and shape up the new songs in preparation for a triumphant “return to form” record.

The group was now razor-sharp musically, with nine new songs battle tested and well honed. Some unaired demos like “Galleani” and “Out of Control” also had strong potential. If this was not quite enough ammunition for a new album, the reimagined “In the Pouring Rain” suggested that the unit—or at least Strummer and Sheppard—might be able to create other potent new songs in short order.

Indeed, Vinyl had tried to kickstart the collaboration by bringing the two together in a hotel room on the US sojourn. A tour can prove a difficult venue in which to midwife new material, however, and there were no results from the meeting. “I took it as a compliment,” recalls Sheppard, “but it seemed a bit forced really.”

Given that finding a new songwriting partner could relieve some of the weight on Strummer, it seemed worth a second try. Yet no such opportunity for swift entry into either a studio or creative collaboration appeared to be in the offing. As White bitterly recounts, after the band’s return “it was just pointless rehearsals for me, Nick, and Pete. Joe was nowhere to be seen. Nor Paul.”

White allowed that, initially, Strummer’s absence did not seem worrisome. Even before America, the singer “was turning up less and less to rehearsals. I don’t think it was because he couldn’t be bothered, but more that he was extremely self-conscious about his voice . . . He seemed more comfortable singing in front of forty thousand people than four.” But as days stretched into weeks, concerns mounted.

Sheppard remembers how an uncertain stasis became the new reality: “As soon as we got back from America, it started to get very weird, dysfunctional, straightaway. Joe disappeared from rehearsals . . . We didn’t really see him. Paul was around sometimes, and not around other times.”

This was a jolting turnabout from the constant motion to which the new members had become accustomed. More to the point, it seemed at odds with the talk of a platoon bonding under fire, the urgency of The Clash’s unfinished job, the promises of a new record knocked out swiftly, with fire and finesse.

One key player was not making himself scarce, much to the chagrin of White: “Bernie began turning up more and more at rehearsals . . . delivering spiteful verbal tirades at the three of us, making sure we knew how inadequate we were, how tenuous our situation was, how we had to be more ‘happening.’”

While Sheppard and Howard were perhaps more immune to Rhodes’s harangues than White—“I tried to build a thick wall in my brain against [the attacks] but it kept falling down”—it left all of them even more confused and demoralized.

Rhodes was privy to a bigger picture and perhaps feared Strummer was slipping out of his control. In part, this was because family life had reclaimed its priority upon the singer’s return. Strummer surely needed time to regenerate and reconnect with his wife and daughter, but such concerns had little place in Rhodes’s vision for The Clash—hence his squeeze on those still in his grip.

According to Chris Salewicz, “Bernie didn’t believe that the group was yet ready to record.” Rhodes: “The live thing was working, but Joe wanted to rush into the studio. He was worried when he heard Mick was getting [a new band] together.”

Both Rhodes and Vinyl also believed the band simply didn’t yet have enough top-notch tunes. As the latter explains, “After the US tour, Joe was trying to come up with material and do lyrics. Meanwhile, the other guys were in rehearsal with on-site recording facilities—and what did that produce?”

Sheppard, White, and Howard unanimously agree that they were never encouraged to write new songs, but instead were asked to rearrange existing Clash songs or record covers. Vinyl remembers it differently: “All of them were asked to record something they wanted to record. It turned out to be covers because there wasn’t anything else to record . . . It became apparent that they were not songwriters,” at least not of the caliber that The Clash required.

The situation bred contrarian responses. Sheppard: “I recorded The Temptations’ ‘Just My Imagination’ because it was the least punk thing I could think of.” Vinyl admits that the trio “weren’t taken on board as songwriters,” but still insists, “The opportunity was there.” Sheppard’s response: “I worked on a funk riff at nearly every sound check on the US tour hoping that Joe would pick up on it, but he never even noticed, to my frustration.”

Sheppard understood a deeper challenge, the result of being a latecomer to the band: “If you’re going to write songs with someone, you need to be their equal. Your voice needs to be heard and appreciated. There is also the question of the magic that needs to happen, and that needs to be allowed to happen.” The perpetual boot camp created by Rhodes hardly nurtured creative expression.

The main exception had been “In the Pouring Rain.” Vinyl granted, “Something good had become even more impressive” thanks to Sheppard and the others. Even so, “The time it took to happen was too long . . . We just didn’t have the time.”

Sheppard had his own analysis: “I need to be able to hear something in a song that inspires me to take it somewhere. With some of Joe’s songs, I didn’t—and when I did, the ideas were apparently not good enough,” at least for Rhodes.

This remains—in Sheppard’s words—“a bone of contention” within the neo-Clash camp. It is true that, despite later missteps, Jones had helped set a very high artistic standard. Vinyl: “It was intimidating. Look at what you are competing against—that immense Clash catalog! No one thought it would be easy.”

This was a key crossroads for the platoon. That this collaboration really wasn’t even tried suggests either cynicism underneath the idealistic rhetoric or—more likely—exhaustion.

Whether by design, miscommunication, or necessity, Strummer now felt the creative weight resting on his shoulders alone. Vinyl: “I don’t think Joe thought it was going to be as hard to come up with material as it turned out to be. As Joe came to see more was on his plate than he realized, the pressure compounded.”

Sheppard: “With the benefit of hindsight, I’ve no doubt that huge amounts of thought were being given to how the record would be made. Of course, no one communicated this to us; it would have been too direct and sensible.” As it happened, he was correct—but in ways no one could have guessed.

The germ of a shocking twist was growing in Rhodes’s mind. Unbeknown to all save perhaps Vinyl, the manager had begun to doubt the wisdom of a return to the sound of the first record. Rather—in an ironic echo of his nemesis Jones—Rhodes now wanted a great musical leap forward.

This ambition fell within the best Clash tradition, and Vinyl would later claim that “a return to the first record was never our intent.” This contradicts Strummer’s own words, but also begs a fundamental question: how could this be done? Given Strummer’s own raw rock proclivities, and the reality of personnel chosen to undergird the “back to basics” drive, it was hard to see how a vaguely imagined reinvention of The Clash could be realized.

Rhodes did not yet have answers for this conundrum. It may have served his purposes for the momentum of the US tour to ebb, and for Strummer and the band to remain—for now—in creative and personal stasis.

* * *

Meanwhile, the miners remained stalwart, but the defeat at Orgreave convinced their leadership that the present course was untenable. While left-wing critics like Alex Callincos and Mike Simons of the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP) argued, “The Battle of Orgreave could have been the beginning of a real attempt to win the strike by mass picketing,” soon the pickets were sent elsewhere.

The coking plant would never again see mass picketing. As the SWP duo lamented, “In the wake of the police riot at Orgreave, many people were sympathetic to the argument that the police were now unbeatable. The miners had tried to use the methods of 1972, and had failed.”

Although Callincos and Simons disagreed with the idea that the miners should concentrate on “winning wide sympathy . . . building a broad alliance around their objectives,” it was hard to deny that Thatcher had learned the lesson of Saltley Gate. Her newly militarized police force had proven its worth in turning back the miners—and now Thatcher sought to win the public relations battle as well.

She got unexpected aid in this mission when the BBC implicated the miners in sparking the Orgreave violence by inaccurate editing on its evening broadcast. By placing images of miners fighting back before images of the state-sponsored brutality, the program suggested the police were simply acting in self-defense. While a later edition corrected the order of events, the damage was done.

A mock-up of the blocked Sun cover. (Artist unknown.)

This error was mild compared to the daily deceit dished out by British tabloids, chief among them the Sun, owned by right-wing media mogul Rupert Murdoch. Sensationalist in their coverage and hewing only loosely to journalistic ethical conventions, these newspapers were also entertaining and popular.

Following Murdoch’s lead, other tabloids excoriated alleged union corruption and violence. One planned Sun cover portrayed Scargill as Adolf Hitler, raising his arm in a Nazi salute next to the headline “Mine Fuhrer.” While this cover was ultimately scrapped thanks to the refusal of the unionized Sun workers to print the paper, others nearly as provocative appeared regularly at newsstands.

This relentless assault by right-wing scandal sheets was effective in swaying public opinion. They were aided by the timidity of the more mainstream press, whose “objectivity” often appeased the government. The clearest evidence of this came when only one of the seventeen major UK papers published the iconic John Harris photo of the unprovoked police assault on Lesley Boulton at Orgreave.

The result was predictable. On June 30, the Economist reported that only 35 percent of the British public supported the miners. A Gallup poll in July showed that 79 percent disapproved of the methods used by the NUM. Both confirmed—in the words of Thatcher biographer Moore—“a growing view that the NUM, and Scargill in particular, were committed to unjustified violence.”

This was precisely the narrative that Thatcher sought to foster. On May 23—before the confrontations at Orgreave—she spoke of “an ugly streak of violence” that “has disfigured our television screens night after night. Reports appear of those who have been intimidated because they seek to go to their place of work, to pursue their occupation, and to support their families . . . Trade unions were founded to protect their members from threats and bullying. And yet there are leaders who could say the word to stop violence, but who fail even to condemn it.”

This spin was inspired, reframing flying pickets as “violent” and the maintaining of union discipline as “intimidation.” Even as police roadblocks made a mockery of freedom of movement and speech, and Thatcher unleashed the power of the state to tap phones and sow chaos inside the NUM, the true threats to freedom and democracy were . . . miners struggling to save their livelihoods.

The police even claimed that Scargill was not attacked, but had simply fallen down and hit his head. In the highly charged atmosphere, it was hard to know what to believe, unless one witnessed events directly. With the combined might of the state, the police, and the corporate media, Thatcher and Murdoch were able to largely control public perceptions in ways that Orwell had warned about.

Yet as Callincos and Simons note, “The defeat suffered by the miners at Orgreave had a contradictory effect.” Even as the skewed coverage led much of the public to question the strike, the brutality led a smaller but still significant group “inside and outside the mining communities to think about [the strike] in much more general political terms, as a broad class issue.”

The miners, then, had potential new allies. While most were from the larger labor movement, others came from more unlikely sectors. This solidarity from a committed minority of the broader public gave hope to the striking miners.

“The battle is getting hotter,” Strummer sang in “Armagideon Time,” and there could be no truer summation of Great Britain in the summer of 1984. Yet as the moment cried out for action, the singer was paralyzed. After eight months of nonstop motion, he was exhausted, hurting, brooding about choices made.

Gaby Salter was overjoyed to have her husband back, even if he seemed dogged by shadows she didn’t quite understand. “Initially I thought perhaps he was out of touch through living in the bubble of the world of The Clash for so long,” Salter recalls. “I never doubted Joe’s integrity at the time but I do think that he was pretty naive and allowed himself to be hoodwinked, especially by Bernie . . . I sat back silently waiting for [the new Clash] to implode.”

This could surely happen—but Strummer might come apart first. Salewicz: “Joe [was] coming out with all that stuff about going back to basics, but if you look at him, the state of his soul [was] fairly evident. You’re not convinced that he’s convinced. He also seems extremely angry . . . actually imploding with anger.”

In “Clampdown,” Strummer argued that “anger can be power.” Clearly that emotion had driven many of his greatest achievements. But anger directed within can turn poisonous. Salter: “It wasn’t till later that I recognized what was happening: Joe was depressed.”

This was not a new issue. In 1982, Strummer had spoken about his ongoing struggles with Mikal Gilmore: “Suicide is something I know about. It’s funny how when you feel really depressed, all your thoughts run in bad circles and you can’t break them circles. They just keep running around themselves, and you can’t think of one good thing, even though you try your hardest.” While Strummer added, “But the next day it can all be different,” his road had remained rocky. Salter also knew what few others did: Strummer had returned home to find his mother was likely terminally ill, facing a struggle with cancer.

Vinyl also knew about this latest heartbreaking development, but wasn’t in a supportive mind-set. Similarly exhausted by the uphill grind, and burned out on the music business rat race, Vinyl had put Rhodes on notice of his desire to leave. He had not yet told Strummer or Simonon, fearing that they would feel betrayed and even more burdened—especially the struggling singer.

As Vinyl remembers, “The situation in the band at the time didn’t take into account any domestic or personal issues . . . Joe was not in a sympathetic environment at all. We were pushing toward something crucial and everything else was secondary.” The consigliere later admitted, “That lack of support is very hard and ultimately not sustainable. But that wasn’t my perspective at the time, I wasn’t thinking of sustainability at the time—none of us were.”

Strummer was stretched to the limit. Salewicz: “Now his mother has got cancer, Joe’s going to visit her regularly. He’s been in a crisis really ever since Mick’s kicked out of the group, but it’s like . . . there’s a succession of kind of plunging ravines that he’s crashing down.”

Strummer might not have acknowledged this, for as Salewicz sadly suggests, “He’d run a mile to get away from his emotions.” This was the unreconstructed masculinity shared by most in Strummer’s peer group, heightened by his fraught history with his parents and his harsh experiences of English boarding school.

“Joe went to public school—not what they are in the US, but these elite boarding schools—and the British public school boy of that time had the bit of your brain that connects to your emotions severed on your first day,” Howard says. “Anybody who feels any emotion is bullied mercilessly . . . it’s not seen as the proper thing to do. I know quite a few public school kids of Joe’s generation, and they haven’t got a fucking clue what’s going on in their own heads and bodies. They’re not allowed to be in touch with it.”

Howard continues, “Such kids are usually wealthy enough, or arrogant enough, or educated enough, or connected enough, that feeling or expressing their emotions isn’t essential—they’re protected from on high. It becomes a habit, hard-wired into you, that you can push all of that down . . . because there are other things that’ll help you through, like money and property.”

Strummer was never in this crowd’s top echelon, and had stripped away as much of his privilege as possible. But some bits went too deep for easy extraction. Feeling desolation, yet wishing to project positivity, Strummer rarely admitted to his darker emotions. When he did, it was sometimes expressed in artistic terms.

As ex-Clash comrade The Baker explained, “The concept of ‘not minding that it hurts’ [was] something Joe was very conscious of.” Evoking the example of Lawrence of Arabia “and the abuse he allowed and willingly encouraged at the hands of the RAF-enlisted men after the war,” The Baker went on to recall how “Joe went through his own short phase of masochistic indulgence when in 1977 he would slick back his hair, dress like a Teddy Boy, and go off to rockabilly shows and pubs that were famous for being in Teddy Boy territory.”

As the “Teds” were the deadly enemies of punks, this risked violent attack. Indeed, The Baker recounts, “This tempting of fate, of pushing the envelope further and further, resulted in Joe being badly beaten one night by a Ted in the toilets at the Speakeasy.” When visiting at London’s Western Hospital, The Baker asked the battered singer about deliberately courting assault: “I remember vividly Joe’s response: ‘If you want to create, you need to suffer.’”

Nineteenth-century British essayist Thomas de Quincey put the notion in more lofty terms: “Either the human being must suffer and struggle as the price of a more searching vision, or his gaze must be shallow and without intellectual revelation.” This idea was central to Strummer’s creative impulse, and part of why he remained deathly afraid of the isolating, cocoon-like life of rock stardom.

The “redemptive suffering” motif wound through many of the singer’s inspirations. Jesus proclaimed, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” and his path was known as the “Via Dolorosa,” the way of suffering. Rastafarian reggae pioneers like Bob Marley celebrated the “sufferers,” the poor in the shantytowns like Jamaica’s Trench Town.

Strummer found great power in music created out of such oppression. In one interview on the 1984 US tour, he linked reggae and the blues in this regard: “When I heard those blues singers I knew it was for real. ’Cause what did we [British] have? Cliff Richard, Lonnie Donegan, Straightsville. But Howlin’ Wolf, he shouts to the top degree; everything comes out. It’s not feeble, it’s gnnrrraaahh, gnnnrrraaah, and you know it is born out of sufferation.”

“Sufferation” is a Rasta term meaning suffering, especially due to poverty or repression. Strummer explained, “Down in Jamaica, sufferation is like something that’s in the air.” When he tried to outline to the interviewer why The Clash had lost its way, he reached for similar metaphors: “We lost that ghetto direction, the direction of the sidewalk, of concrete, and of hunger.”

The intertwined roles of pain and anger became obvious when Strummer explained his approach to writing: “I tell you what I do—I plug into the world. When I hear about the terrible things that are going down, it throws me into a rage and so it prompts me to write and sing songs about it.”

This explanation made sense. Yet Strummer’s life was on a trajectory away from the street, ghetto hunger, and sufferation. Even if he did not act or look a stereotypical millionaire property-owning father with a wife and a young child, this was his life now. This longtime squatter who had emulated Woody Guthrie’s hobo life was drifting back toward the privilege he had scrubbed away.

There surely was pain in that realization. But what if this agony—fearing that one had become a hypocrite, a failure, a sellout—paralyzed instead of catalyzed? Can this burning-fear-verging-on-self-loathing be turned into art that matters, that can change lives, maybe even change the world?

* * *

Strummer struggled to find that revelation as anger and pain threatened to boil over in his homeland. Thatcher was pressing her offensive against the miners on several fronts at once. In principle, the strike was a simple dispute between workers—the NUM—and their employer—the National Coal Board—with an impartial police and judiciary merely refereeing. Yet few doubted that Thatcher was truly the general commanding the entire campaign, bending public institutions to serve her wishes.

Seeking to encourage a trickle of striking miners returning to work as their hardships grew, Thatcher pushed the police out of relatively friendly environs like Nottinghamshire into areas solidly behind the strike. The resulting hostile occupations bred backlash. Callincos and Simons: “Whole mining communities rose up in revolt with women often playing a leading role . . . On July 9 the first pitched battles between police and Yorkshire mining communities occurred.”

Thatcher encouraged two Nottinghamshire miners who were bringing a legal case claiming that the NUM had attempted to embroil them in an unlawful strike. If favored by the court, this would allow the Tory government to “sequester” the union’s funds, crippling its ability to meet the needs of its striking miners.

Strikers don’t get their wages, only a meager union stipend, so many families were already eating at community soup kitchens. Their prospects became even bleaker on July 26 when Parliament enacted the Trade Union Act. As a result, neither striking miners nor their families were entitled to state benefits. The children of strikers could not receive free school meals or social security help with school uniforms.

The growing suffering fed fury at those who crossed picket lines. In August, the Rhymney Valley Miners Support Group issued a front-page editorial, “What Is A Scab?” in the Rhymney Valley News. To the authors, the dictionary definition—“an unpleasant crust of dead tissue”—seemed apt to describe those returning to work: “Such a person is a scab on the face of the community. As far as the miners of [South] Wales are concerned, there is nothing so low as a man who will stab his fellow workers in the back by strike-breaking.”

The barely contained fury of those words foreshadowed agonizing fractures to come. As hunger became rife, miners faced a dilemma: return to work and be viewed as a “scab,” ostracized in your own community; or stay out and live primarily on the most meager of handouts. The vast majority chose the latter.

When a dock strike in mid-July opened a second front, the miners’ hopes rose. The Tory government was in danger of defeat—and was preparing extreme measures to prevent that eventuality. As the Guardian reported years later, “Margaret Thatcher was secretly preparing to use troops and declare a state of emergency . . . out of fear Britain was going to run out of food and grind to a halt.”

The Clash on the docks, mid-1984, before Strummer’s disappearance. (Photo by Mike Laye.)

The prospect that a broader Britain would face the deprivation that miners and their families endured daily no doubt cheered some—but it was not to be. Under immense pressure from the Tories, the dock strike collapsed within two weeks.

Nonetheless, the threat of union solidarity remained. As Moore recounts, “Scargill at Orgreave exorcised for Mrs. Thatcher the demon of Scargill at Saltley twelve years earlier. It did not automatically follow, however, that the government would win. It remained possible that key trade unions would combine successfully against it.”

Britain’s north was now in turmoil, with the strike impacting the daily lives of millions. Although the south was less contested, the chaos was spreading. Thatcher aide Andrew Turnbull allowed, “‘The Battle of Orgreave’ recalled ‘the Wars of the Roses’”—an admission that something akin to civil war had broken out.

He was not the only one to come to this conclusion. As Moore writes, Thatcher aide David Willetts “recalled that when working for Mrs. Thatcher during the miners’ strike the comparison with a civil war was apt. ‘You would be in a meeting with Mrs. T on some other subject and messengers would come in with reports like “Kent is solid . . . Nottingham is with us . . . Yorkshire is in rebellion.” It did feel like a scene from one of Shakespeare’s history plays.’”

Thatcher again sought the rhetorical high ground, painting the miners not simply as her political opponents but enemies of the country. According to the Times of London, “Speaking at a private meeting of the 1922 Committee of Conservative backbench MPs at Westminster [on July 19], Mrs. Thatcher said that at the time of the Falklands conflict they had had to fight the enemy without; but the enemy within, much more difficult to fight, was just as dangerous to liberty.”

Such rhetoric had consequences. As Moore admits, it “gave Mrs. Thatcher the permission . . . to have some of the strikers’ activities monitored by the Security Service . . . Stella Rimington, who later became the head of MI5, classified Scargill—whose phone had been tapped for years because of his links with the Soviet-backed Communist Party of Great Britain—as ‘an unaffiliated subversive.’”

While Moore agrees with Thatcher’s use of the phrase “the enemy within,” he distances himself from its impact by noting the obvious: “Being a declared enemy of the government led by Margaret Thatcher did not of itself make anyone a subversive,” i.e., an enemy of democracy.

Even though the details of the “dirty tricks” campaign would not be exposed for years, any careful observer saw the scale of the Tory offensive. It might have been expected to break the will to resist—but the miners persevered. They inspired allies from around the country to organize support groups that channeled food, clothing, and money into the hard-hit mining communities.

Nick Sheppard’s parents joined one such group, which provided a much-needed outlet for the frustrated guitarist. Sheppard: “Vince, Pete, and I worked pretty much a five-day, ten/eleven a.m.-to-six/seven p.m. week rehearsing and doing whatever busy work Bernie devised. We were set various tasks: record a new Clash song—I did ‘Pouring Rain,’ and was told there would be no ‘disco’ on the new record—record a cover, fix guitars, dig a hole, fill it in . . . Mind-numbing repetition, really.”

This would have been trying at any time. But with Britain on fire, this disconnect was incomprehensible and infuriating. Sheppard: “I had gone on marches for the miners . . . and I do remember asking Bernie if we were gonna do any benefits for the miners, because I really couldn’t believe that we wouldn’t. And I wasn’t given an answer then . . . That was difficult.”

Instead, the guitarist for the most popular revolutionary rock band in the world did a benefit for the miners’ strike—arranged by his parents. Sheppard: “My mum and dad live in Bristol, which was close to Wales, one of the centers of the strike. And I did a benefit they helped organize with some other bands and friends of mine. Not as anything to do with The Clash—I just went down to Bristol to play at a benefit to specifically help this one particular town in Wales.” If the show scarcely had the impact of a Clash gig, it at least eased Sheppard’s conscience.

Sheppard was not the only musician whose personal support for the miners’ cause had begun to turn toward acts of concrete solidarity. The Clash’s anarchist nemesis Crass played a miners benefit in July in what turned out to be its final show. Other artists like Chumbawamba, Redskins, Paul Weller, New Model Army, Bronski Beat, and Billy Bragg were preparing to do the same. Even relatively apolitical bands such as New Order joined the cause, as did Music for Miners, a group of writers, artists, and filmmakers aiming to activate the youth.

This fit well with a new strategy of the miners’ movement. With the loss of Nottinghamshire, the defeat of mass picketing at Orgreave, and setbacks in the public relations war, it was becoming clear that the NUM needed broader support to outlast Thatcher. This meant aid from other unions, but also went far beyond.

Peter Carter, the British Communist Party’s industrial organizer, argued, “Trade-union solidarity alone is not enough. A wider public support has to be won for the miners . . . A major industrial dispute of this character cannot be won by industrial muscle alone in the face of hostile public opinion. The miners should concentrate on winning wide sympathy, building a broad alliance around their objectives.”

While reiterating his support for mass picketing, Scottish NUM vice president George Bolton similarly argued, “The government and the [National Coal Board] have consistently tried to contain the argument to the question of mass pickets, violence, and law and order; and they have avoided like the plague any discussion of what the dispute is all about. That tells you that they have a real fear of a mass understanding by the British people of what the dispute is all about . . . The question of the arts is very important. We need to get the world of entertainment identified with us, not least because they get mass audiences.”

Bolton’s words suggested precisely the sort of alternative news network that Strummer and Rhodes had envisioned with the “Radio Clash” concept, and that the band had endeavored to fulfill in its own way. At this perfect moment to push the idea, however, Strummer remained MIA, with The Clash consequently dormant. As Sheppard ruefully recalls, “In terms of discussing the miners’ strike with Joe, on any level, it just didn’t happen . . . because I didn’t see him.”

If Thatcher and Reagan were the “enemy without” for Strummer, he was now contending with his own “enemy within.” Depression was made worse by his addictive tendencies, not only with alcohol, but his old frenemy marijuana.

Strummer had foresworn pot loudly, publicly, and repeatedly. Those closest to him knew it wasn’t that simple. Years later, Salewicz claimed, “Bernie may have said there was a ‘no drug policy’ but Joe was smoking spliffs all the time!” Interviewed in 1999, Strummer agreed: “[The anti-pot line] was Bernie’s new regime. It didn’t last long. After two weeks, we were gagging for it.”

Strummer’s self-deprecating sense of humor may be at play here. None of The Clash’s newer members witnessed such drug use, so Strummer was clearly keeping it close to his chest. Such corrosive secrecy could breed self-loathing as one did in private what one denounced in public. In the same 1999 interview, Strummer copped to “feeling like a no-good talentless fuck” during this period.

The vehemence of his antidrug stand in 1982–84, and the depth with which it was articulated, suggest that Strummer actually believed it—but couldn’t live it. Far from being something forced upon him by Rhodes, Strummer’s stance came from self-knowledge. On the US tour, the singer had spoken of “little gems of wisdom” learned from harsh experience: “I know how to take care of myself a bit more—like I have two beers instead of eight, stuff like that.”

But for an addict such lessons are often beside the point. Bill Wilson, cofounder of Alcoholics Anonymous, argued, “The actual or potential alcoholic, with hardly an exception, will be absolutely unable to stop drinking on the basis of self-knowledge.” Strummer’s ability to translate insights into changed behavior was limited. His most revealing, articulate, and convincing discussion of his antidrug stance—his June 1982 conversation with Mikal Gilmore—was itself lubricated by copious amounts of alcohol, as the writer’s blow-by-blow makes clear.

Strummer was more cognizant than most that human beings can be intellectually aware of some truth without that knowledge producing a change in behavior. The mere fact that Strummer found it so hard to stop using—even for a short time, even when he was publicly committing himself to his audience as well as privately to his band—suggests addiction.

Asked directly about this, Strummer’s friend Salewicz gently notes, “Pot can help you get through a lot.” Strummer was sliding back into self-medicating to ease his pain. While better than his brother’s way, Strummer knew drugs could be “slow suicide.” “I kill my soul / each and every day” ran a line from an early version of “Glue Zombie,” and Strummer now found himself slipping into this limbo.

Salewicz: “The pressure must have felt enormous. The very last thing you would have thought [Strummer] wanted to do was go on the road, breaking in a new group, though . . . this might have been exactly what he did want to do.” Now, Salewicz argues, Strummer was back home and could hide no more from his feelings. “Over the ensuing months he would come close to cracking under their pressure, unable to avoid the messages they were sending him.”

Drugs, like pain, could be a catalyst for creativity—but they could also crush the spark. Strummer found himself in a hurting place, and not an easy spot from which to live out his lofty vision. So he didn’t. He hid away, hoping the pain would somehow translate to inspiration. But months passed, and Strummer remained stuck, isolated from his band and desperately in search of his muse.

In late August, something finally shook loose. Vinyl recalls, “London was feeling oppressive for Joe and I, so we decided to just take off, no agenda except getting out of Dodge for a few days!” Once the penny-pinching Rhodes was convinced to fork over some money, the duo went to the airport and flew to New York City.

Vinyl: “That night in New York we hatched a plan—nothing preconceived—that we would go to Los Angeles and make a record, totally on the fly.” The next day they were off. “I got somewhere cheap to stay and looked for a cheap demo studio out of the back of the LA Weekly while Joe worked on some material—I’m not sure if it was something he had or just made up on the spot.”

The next day, they recruited a mariachi trumpet player and percussionist found at a Sunday brunch. Vinyl: “When I was on the phone with the percussionist, Joe shouted, ‘Tell him to bring all the gear that he usually isn’t allowed to play!’” With musicians in hand, the pair took off to a tiny demo studio for a swift session.

As Strummer hadn’t even brought a guitar, the studio provided one. Much to the dismay of Strummer, it was a jazz-rock guitar with a built-in keyboard, similar to an instrument that Jones sometimes used. “The studio guy was showing us all the sounds it could make,” Vinyl says, laughing. “And finally Joe just said, ‘We ain’t in search of fucking Spock, mate . . . Just make it sound like a guitar!’”

None of the studio folks or musicians connected these scruffy Brits to a Top 10 rock band. Vinyl: “We said we were hustlers just trying to make a quick buck.” Of the three or four songs that the makeshift group knocked out in a few hours, “Three Card Trick” was the only song Vinyl recognized—though this incarnation was adorned heavily with Latin trumpet and percussion.

The impromptu session completed, the duo flew back to New York to remix the demo at another fly-by-night joint—“some place out of the Village Voice classifieds,” says Vinyl—and were off to London the next morning, the entire adventure completed within a long weekend.

It was a startling burst of creative energy, especially given the stalemate Strummer had found himself in for the past three months—but it would go nowhere. Vinyl: “We played the tape for Bernard and he was very taken aback because he thought we were just out getting drunk.”

This “go in and bash it out” session echoed what Strummer had touted as his plan for the new Clash record—only the larger platoon was not involved in any way. In any case, Rhodes was not impressed. Vinyl: “We gave him the tape and it was never talked about again, other than when I once mentioned an arrangement from the session. Bernard was not happy that I brought it up.”

While Vinyl describes the adventure as “great fun,” he is also clearly pained that the tracks simply got filed away. Given Rhodes’s desire for control of all things Clash-related, the outcome is not surprising. Still, it came as yet another blow to Strummer’s shaky creative confidence.

This stasis was costly for The Clash, as well as Strummer personally. As the brutal Thatcherite response to the miners’ strike cast a shadow over the entire UK, the moment seemed ripe for the band to shine. Other performers like Billy Bragg were knee deep in strike support. But as Bragg asked later, “Where was The Clash? They were AWOL, missing in action, nowhere to be seen.”

Bragg was not the only Clash fan who felt let down. Recalling the savage assault by mounted riot police at Orgreave, Clash biographer Marcus Gray noted, “‘Three Card Trick’ and ‘This Is England’ reflect the brutal face of contemporary policing, batons are wielded willy-nilly in both,” only to mourn that “The Clash missed a real opportunity to attach themselves to the miners’ cause at this crucial time.”

It was a massive burden for any person to carry, but Strummer could not escape it. “I really enjoyed being a bum again. I wish I could do it every day, really,” Strummer had told Gilmore in 1982, referring to his disappearance to Paris. “But I can’t disappear anymore. Time to face up to what we’re on about.”

That time was coming around again, for Strummer returned to London to learn that The Clash had been booked to play five shows in Italy as part of the “Festival of Unity.” This was an annual cultural extravaganza sponsored by the Italian Communist Party, an exponent of “Eurocommunism,” which sought to recapture the movement’s original aims, challenging both the US and USSR.

White, Howard, and Sheppard were overjoyed. White: “We were just [feeling], ‘Thank God, we’re going away and doing something, instead of fucking around in a studio every day.’” Sheppard was ideologically pleased as well: “The Communist Party held these huge festivals every year, featuring all different kinds of music, partly to generate funds for the party on the local level—they operate politically at a town council/county council level, with a network throughout Italy—but also to enhance the cultural life of the country.”

The venue, however, posed more questions about the band. As Gray wrote, “The Clash of ’76 had managed to generate a righteous anger and capture the imagination of the country’s youth on far less fuel than [the miners’ strike]. The Clash of ’84 remained on holiday until September of 1984. When they did reconvene it was to play a series of gigs for the Communist Party. In Italy.”

Gray would claim, “The motive was chiefly financial,” but this seems unfair. Three months had passed since The Clash last graced a stage. The battle had grown hotter, but no new songs had appeared, no recording had commenced. Like Strummer, The Clash was nearing a point where stasis becomes disintegration.

The decision to return to the band’s fountain of energy and inspiration—the Clash audience—seemed essential. While it might have been better to be focused on the home front, these shows would help determine if, indeed, a band still existed.

The summer of 1984 had held high drama for Thatcher, with the chances of victory or defeat shifting like the weather. The Coal Board and the NUM were now in talks. One of Thatcher’s biggest worries was that MacGregor would fold under the miners’ pressure and agree to what she saw as an unsatisfactory settlement.

When talks broke down just short of agreement, Thatcher recalled later, “I was enormously relieved.” The government assault was intense and multipronged, and Thatcher’s sense of righteousness remained undiminished, but the miners were proving to be a far more tenacious foe than the Argentinians.

As her authorized biographer Charles Moore recounts, “So uncomfortable did the situation seem that President Reagan took the step, highly unusual in an ally’s purely domestic political difficulty, of writing to Mrs. Thatcher.” Reagan purred encouragingly: “I have thought often of you with considerable empathy as I follow the activities of the miners’ and dockworkers’ unions. I know they present a difficult set of issues for your Government . . . [but] I’m confident as ever that you and your Government will come out of this well.”

Reagan—a leader of the actors’ union in his more liberal days—had faced down many unions himself. Indeed, his destruction of the air traffic controllers’ union in 1981 had been an inspiration for Thatcher, as had his ability to co-opt other unions such as the Teamsters to support his agenda.

He had his own challenges, however. The day after Reagan wrote his soothing words to Thatcher, Walter Mondale mounted the stage at the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco to accept the nomination for president.

Evoking the diversity in the room—“black and white, Asian and Hispanic, Native and immigrant, young and old, urban and rural, male and female, from yuppie to lunchpail”—Mondale dismissed Reagan and his party as “a portrait of privilege” while describing the Democrats as “a mirror of America.” To underline this point, Mondale chose Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate, the first time a woman had gained the vice presidential slot for one of the two big parties in the US.

“Over the next one hundred days, in every word we say, every life we touch, we will be fighting for the future of America,” Mondale proclaimed. “Four years ago, many of you voted for Mr. Reagan because he promised you’d be better off. Today, the rich are better off. But working Americans are worse off.”

Describing the Reagan regime as “a government of the rich, by the rich, and for the rich,” Mondale reached out to communities hit hard by deindustrialization: “Three million of our best jobs have gone overseas. To big companies that send our jobs overseas, my message is: We need those jobs here at home. And our country won’t help your business—unless your business helps our country.”

On foreign policy, Mondale promised to “reassert American values,” pressing for human rights in Central America, the removal of US military advisers, and an end to “the illegal war in Nicaragua”—a direct attack on the current policy in the region. He also blistered Reagan over the nuclear arms race: “Every president since the Bomb went off understood that we have the capacity to destroy the planet and talked with the Soviets and negotiated arms control. Why has this administration failed? Why haven’t they tried? Why can’t we reach agreements to save this earth? The truth is, we can . . . [and] we must negotiate a mutual, verifiable nuclear freeze before those weapons destroy us all.”

Mondale then evoked one of Joe Strummer’s favorite themes: truth. “Americans want the truth about the future . . . Whoever is inaugurated in January, the American people will have to pay Mr. Reagan’s bills. The budget will be squeezed. Taxes will go up. Anyone who says they won’t is not telling the truth.

“Let’s tell the truth,” Mondale called out, building to a crescendo. “It must be done, it must be done. Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I. He won’t tell you. I just did.” As the crowd roared its approval, Mondale returned to the attack: “There’s another difference. When he raises taxes, it won’t be done fairly. He will sock it to average-income families again, and leave his rich friends alone. And I won’t stand for it. And neither will you and neither will the American people.”

It was a rousing speech, a powerful vision for America. Clearly relishing his newfound role as truth-teller, Mondale—long criticized from the left as a timid and centrist “old news” Democrat—seemed ready to take the fight to Reagan.

Across the ocean, another vision had risen. SEX STYLE SUBVERSION read the banner across the back of the stage at Stadio Simonetta Lamberti, a soccer stadium in Cava de’ Tirreni, a small city adjacent to Naples in southern Italy. The provocative yet vague banner—not glimpsed since its debut at the US Festival—seemed an odd match for a socialist band playing a Communist festival.

As a crowd of 15,000-plus roared approval, a slender man with spiky hair strode to the microphone and let loose: “Hip-hoppers! Punk rockers! Young ladies! Show stoppers! The . . . Clash . . . are . . . out . . . of . . . conttrrroooolllllll . . .”

As the words reverberated through the stadium, Kosmo Vinyl walked away, his words followed by the spaghetti western tune “Sixty Seconds to What?” While the music swelled, the staccato chords of “London Calling” split the night air. The crowd erupted in waves of pogoing as The Clash burst into the light.

The sound was tight, seemingly unstoppable. Few outside the band’s inner circle could have guessed that the very first time that the entire five-man unit had been together in over three months was several hours earlier for sound check.

Sheppard recalls, “We didn’t rehearse once for the shows in Italy. We just went and did ’em. We didn’t see Joe until he was sound-checking in Naples.”

As it happened, Strummer had arrived in Naples days earlier, but passed up connecting with the band to go out with some locals. Italian fan Luca Lanini remembered, “Joe was in Naples a couple of days before the gig and became friends with some juvenile delinquents of a notorious central slum named Quartieri Spagnoli. He roamed around town with them on the back of their scooters.”

The company Strummer was keeping and his somewhat rumpled appearance led to trouble when he tried to visit the National Archaeological Museum. Lanini: “Joe wasn’t allowed to enter because of his Mohican haircut and his lion-tamer jacket.” After a frantic series of calls, journalist Federico Vacalebre—who had written the first Italian book about The Clash—was summoned and succeeded in getting Strummer into this hall of hallowed antiquities.

The band knew none of this. Asked if Strummer offered any explanation or apology for his extended absence, Sheppard responded simply, “No, he didn’t.” The sound check itself consisted of Strummer barking out “‘Be-Bop-a-Lula’ in F sharp!” and the band doing a swift run-through of the Gene Vincent classic.

Given all of this, the show went off astonishingly well—a tribute, surely, to the work Howard, White, and Sheppard had put in on their own, with an occasional assist from Simonon. The set didn’t stray far from that established on the US tour, although several key new songs like “Pouring Rain,” “Jericho,” and “The Dictator” were missing. The night also saw the return of the much-maligned “Should I Stay or Should I Go” in the second encore.

The most intriguing moment came six songs into the set when Strummer stopped to query the crowd: “You must know that we are English, right? Inglese . . . This is what it is like in England tonight!” On that cue, Sheppard hit chunky guitar chords reminiscent of the Modern Lovers’ protopunk classic “Roadrunner” and the band launched into a revamped “This Is England.” If not nearly so fully renovated as “Pouring Rain” had been, the song—which could sometimes seem a bit stiff—benefited from the more even tempo and improved dynamics.

Beyond showing that the newer members had continued to stretch and shape the songs, this suggested that—all appearances to the contrary—Strummer was following events on the home front closely. He was nonetheless barely more engaged with the band on this tour than he had been since June, traveling on his own, regularly drinking to excess, seeming detached and aloof.

To White, Strummer was “out in the stratosphere . . . not exactly a space cadet, more like the galactic general.” Sheppard was a bit kinder if no less concerned: “Joe was drunk pretty much all the time. Sometimes it was good value, other times he was best to avoid. I think he was really upset, hurting.”

An interview with Vacalebre after the Naples show provided a glimpse of Strummer’s bleak frame of mind. Asked about the Sex Style Subversion backdrop, the singer offered a laconic response: “These three words represent us, we can’t do without it.”

When Vacalebre brought up the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the Greenham Common Peace Camp, Strummer dismissed the groups, saying, “We are not interested in them,” explaining darkly, “War is everywhere, inside us, there is no other peace than what we have now, which is armed, nuclear. Our life is at the maximum peace we could possibly have, unfortunately.”

Strummer then expressed similar disdain for the massive marches a few months before, saying simply, “Bob Dylan sang about it in 1963.” This seems a reference to “Blowin’ in the Wind,” a protest song steeped in despair; in the words of rock critic Mick Gold, it was “impenetrably ambiguous: either the answer is so obvious it is right in your face, or the answer is as intangible as the wind.”

Strummer—allegedly hard at work on new songs for months—also had some startling words to share on that front: “After the tour we’ll concentrate on writing new material. You’ll be surprised when you listen, you’ll snap your fingers, you’ll howl with wonder, it will be different from what you’ve heard to date. Maybe it will be pop, at least in part, and will appeal to women too. You have my word.”

Strummer only became genuinely effusive when speaking about his recently made comrades, mixing praise for them with a swipe at his home city: “Those street kids have become my friends, introduced me to Naples, such an old, charming city . . . I saw where they live, where they have fun, what problems they have finding work, or having sex with their girlfriends. I liked Naples, it’s alive, sunny, carnal, sensual, not depressing and boring like London.”

Strummer sounded fatalistic and unmoored, but there was one upbeat development when the band finally came back together. Much to Sheppard’s pleasure, “Joe wanted us to stretch out musically . . . He was really pushing us to jam at the gigs, maybe to test our suitability for the planned new Clash record.”

This began to show on the second night, September 7 at the Palasport Arena in Rome, another spacious stadium filled with fervent fans. “London Calling” once again opened, this time featuring an extended guitar intro with first drums and then bass phased in bit by bit. The music built gradually and then pulled back to welcome Strummer—fully two and a half minutes into the song—before blasting off.

An extended quiet section also appeared late in “White Man in Hammersmith Palais.” As with the opener, this was a powerful addition, making space for a graceful crowd sing-along and some melodic guitar passages.

Strummer was very animated onstage, trying out more of what White called his “pidgin Italian” to engage the crowd. He gave an apparently spontaneous—and somewhat off-color—introduction to “Rock the Casbah,” asking the crowd if they know what a “casbah” was. With no answer forthcoming, Strummer held forth: “The casbah in the Middle East is where you go to get down with something, maybe hear some dirty rhythm or something funny with a snake or if you want to do something with a donkey!” Regardless, this proved to be another powerful show, maybe even better than the night before.

While the band grew more musically assured with each day, Strummer was in a downward spiral. Salewicz writes, “Joe went on a three-day bender, guzzling bottle after bottle of brandy. Raymond Jordan was appointed to babysit Joe through this crisis.” Howard remembers Strummer “screaming in the hotel bar,” and both he and White recollect band meetings where Strummer outdid Rhodes in verbal abuse. “As though Joe was acting as manager, everyone was torn to pieces,” Howard says. “Usually these events ended with someone in tears.”

Strummer’s erratic behavior was obvious the third night, at Stadio Mirabello in Reggio Emilia. The show started off strong again, with the extended “London Calling,” followed by fierce versions of “Radio Clash,” “Safe European Home,” and “Career Opportunities.”

Strummer then paused to bring on a young female fan he had met earlier in the day to serve as translator. Calling her “honey” and “baby,” the boozy singer launched into his appeal, which the Italian gamely translated: “Has anyone noticed OUT THERE . . . They have all the bookshops, all the bloody restaurants, everything . . . How come I stand here in this SHITHOLE without even a toilet!?”

The crowd roared, and Strummer answered his own question—“Because they’ve taken all the money!”—and turned back to the woman, ordering her, “Now tell them, ‘Let’s get down!’” As puzzled fans struggled to absorb this, Strummer coached his admirably patient translator through introductions of White, Howard, and Simonon. Finally, the singer introduced himself, with self-loathing nearly dripping from his tongue: “My name is the biggest fucker in the world! Get it?”

Strummer dismissed the woman with a curt, “Grazie, baby,” and shouted, “Here is Signore Nick Sheppard!” Amazingly, the transition was seamless. When the guitarist ignited “Police on My Back”—which had now become his main vocal showcase—the set finally emerged from the theater of the absurd.

After urgent versions of “Are You Ready for War?,” “White Man in Hammersmith Palais,” and “Three Card Trick,” Strummer paused again, this time to ask the crowd for requests. When an audience member called out for “Lover’s Rock,” the frontman responded with apparently genuine shock: “‘Lover’s Rock’!? Are you sure about that? You must be crazy, man, you must be crazy!”

It was a bit of inspired humor, taking dead aim at one of the least successful Clash songs ever—but then Strummer went on to yell, “We’re all fucking crazy!”

Such a clichéd rock and roll outburst seemed desperately out of character.

While the band swiftly launched into a slam-bang rendition of “Complete Control,” Strummer seemed anything but in control—a point underlined when the singer then introduced the feminist epic “Sex Mad War” by praising “the nice-looking women in Italy . . . bella bella bella!” Once again, the performance was dynamic. But even though the rest of the set was equally fervent and well played, no sober observer could fail to be concerned about Strummer’s condition.

If anything, the tour’s final show at Genoa’s indoor Arena Palasport before more than ten thousand spectators on September 11 was even more electric and chaotic. White later described the show as “a riot,” and he was not far off the mark. In many ways, the evening was a classic Clash performance, with just enough unpredictability and danger to keep any showbiz boredom fully at bay.

Introducing himself as “Harry the Fucker,” Strummer once again put the knife in his own chest. Beyond that, he led the band through one of its most dynamic, wide-open shows. Sheppard recalls, “Joe was wild and excitable and wanted us to stretch out musically.” One of the fruits of this came early in the set: a gorgeous “Spanish Bombs” that began almost a cappella with Strummer singing over somber drums and muted guitar before building to a ferocious climax.

If Strummer was a bit “off the rails”—in Sheppard’s words—it could make for compelling theater. “Are You Ready for War?” started strong but partway through Strummer went off, abandoning the usual lyrics, ranting and raving. The band valiantly stuck with the singer, until he literally waved them off, barking an order for them to go into “White Man in Hammersmith Palais.”

The band complied, but as Strummer hit the song’s climax, he suddenly stopped. Yelling, “Venga! Franco says it’s cool . . .”—apparently a reference to Italian promoter Franco Mamone—the frontman started inviting the crowd onstage.

It is not apparent why Strummer did this. Sheppard later speculated that the singer was bored and simply wanted to interrupt entertainment-as-usual. It is also possible that he may have felt too much distance from the crowd.

A few days before, Strummer had defended playing in this series of huge venues: “It’s the only possible way. We cannot do five concerts in Genoa, five in Naples . . . Can you imagine what would happen if instead of being here we chose a small club? We do not want thousands of people forced to stay out of our concerts for the enjoyment of the privileged few.”

This made sense. Yet this stance directly contradicted what Strummer had told another journalist seven months before. Vowing to play seven nights in one city if need be, Strummer had insisted, “We want to be bigger than anyone else but do it in a way that matters.” Both Strummer and Simonon had often talked about the catalytic role of the crowd in fueling their performances. As such, they mourned the loss of intimate connection as their concerts’ scale grew.

Whatever Strummer’s reasoning, the barrier between artist and audience had been obliterated. Chaos reigned for several minutes as Strummer alternated between exhorting the crowd—“Italy, come on, come on!”—and wrangling with skeptical security. Once the stage was finally full, Strummer led the band back into a reprise of “White Man,” the crowd and band singing and moving together.

Sheppard: “I thought it was great! We ended up on the drum riser as our stage. We had to leave the stage after one song. When we came back there were no monitors and one microphone!” Nevertheless, the next half hour of the show was a steamroller, going from punk to dub and back again.

An equipment breakdown stalled “I Fought the Law,” but the band took the opportunity to uncoil an extended dub breakdown leading into “Bank Robber,” followed by “Janie Jones.” The band then kicked off “Tommy Gun”—only to take another left turn as White was unceremoniously pulled into the crowd.

White: “In ‘Tommy Gun’ I would take a sudden run to the edge of the stage, stop, lean over, and fire an imaginary salvo. It was great fun . . . until some bright spark in the audience grabbed the guitar’s machine head and wouldn’t let go . . . It was either me or the instrument so in I went!”

Sheppard: “All the crowds on that tour were really wild . . . I remember Vince getting pulled into the crowd and coming out with a shoe missing and his clothes fucked up.”

When the song ended, a ragged White clubfooted it over to Strummer and asked for the band to go offstage so he could get a new pair of shoes. The singer was not having it. As White later wrote: “Joe glared menacingly at me. I don’t think he saw me, not a bit. It was eerie. Eyes glazed, and like the messiah calling his followers to prayer he stooped low, and pulled the microphone to his lips . . .”

While the dazed guitarist looked on, Strummer slowly intoned, “ENGLISH . . . CIVIL . . . WAR!” White: “The crowd erupted. I started smashing out tuneless chords in wild abandon. A few people jumped up onstage and started leaping around. I quickly forgot how stupid I looked. Suddenly all the madness made sense.”

With glorious chaos swirling around them, the band quickly knocked out two more numbers before exiting the stage: “Know Your Rights” and “Magnificent Seven.” At the end of that shimmering punk-funk juggernaut, Strummer screamed, “I . . . WANT . . . MAGNIFICENCE!”

But what made for a gripping performance didn’t necessarily align with mental health. While the show had been riotous, the after-show drama would be as well. While Sheppard, Howard, and Rhodes shared a meal at a fan’s restaurant—“One of the only times I enjoyed Bernie’s company!” laughs Sheppard—White, Vinyl, and Strummer descended into something close to hell.

It began as just another night of hard drinking and skirt chasing—but soon took a much darker turn. According to White, after the trio tired of the bar, a wretchedly drunk Strummer suggested that they go in pursuit of prostitutes. “Joe assured me it was great. A real experience. It had to be tried,” White says bitterly.

When this pursuit was unsuccessful, a new drinking spot was found. Once there, White remembers, Strummer and Vinyl began to badger him about his guitar playing and supposed lack of commitment to The Clash. Startled, White tried to defend himself, only to face more barbed insults.

When Strummer upped the ante by insinuating that he had slept with White’s girlfriend and then summarily dismissed White from the band, the guitarist lost control and began to slug the singer in the face—but he faced no resistance. Suddenly, Strummer and Vinyl were laughing, claiming it had just been a test.

White felt sickened—yet this was not the end. The next day, Pearl Harbour got a call from her husband, Paul Simonon. As Harbour later told Chris Salewicz, “Paul says, ‘Last night we all got drunk, and Joe and Kosmo told me that I had to divorce you or quit the band.’ I said, ‘What did you say?’ I was livid. He said, ‘I don’t know what to tell them.’ I said, ‘Fuck you. Divorce me if you want.’”

While the two eventually sorted out the matter, a furious Harbour took her revenge upon Strummer upon his return to Heathrow Airport, kicking and punching him in public while roasting his hypocrisy. Harbor: “‘You, Joe Strummer, you think it’s not rock and roll for Paul and me to be married, and you walk around London pushing a pram with an orange Mohican. You are a fucking idiot!’”

The double standard was real. As with White’s attack, Strummer didn’t resist—he just took the blows, as if hoping that the pain would somehow be redemptive.

While Harbour made enough of a ruckus to attract the attention of nearby police, the two patched it up by—ironically, given the role of alcohol in the initial fiasco—going out drinking the next night. Displaying the scabs on his shins to all who cared to look, Strummer found an unusual way to apologize. Harbour: “Joe took off my high-heeled shoes and poured champagne in them and drank it.”

But if Strummer’s relationship with Harbour was mended, other wounds were not so easily healed. Nor were the injuries caused to the unity of the band. What is one to make of this ugly series of events? Offering no excuses, but with clear regrets, Vinyl will only note that this period was “the unhappiest time of my adult life.” If anything, Strummer seemed even more lost and forlorn.

Yet, against all odds, the tour had been a success. Sheppard told Gray, “The shows were really good, and we played really well,” later adding, “The gigs were full of freedom and experimentation musically, and we felt confident as a band. I loved the whole experience—the food, the people, the country.”

While Sheppard admitted, “I didn’t really pay too much attention as to why Joe was off the rails,” this would become increasingly difficult. Strummer had once said his 1982 disappearance was a way of working himself out of a depression: “I had a personal reason for going . . . I just remembered how it was when I was a bum, how I’d once learned the truth from playing songs on the street corner. If I played good, I’d eat. That direct connection between having something to eat and somewhere to stay and the music I played—I just remembered that.”

The singer was shrouded in shadows he seemed unable to shake. The dream of a reinvented Clash able to face whatever 1984 had to offer was fading away.

Soon enough, Joe Strummer would again disappear.