chapter six

got to get a witness

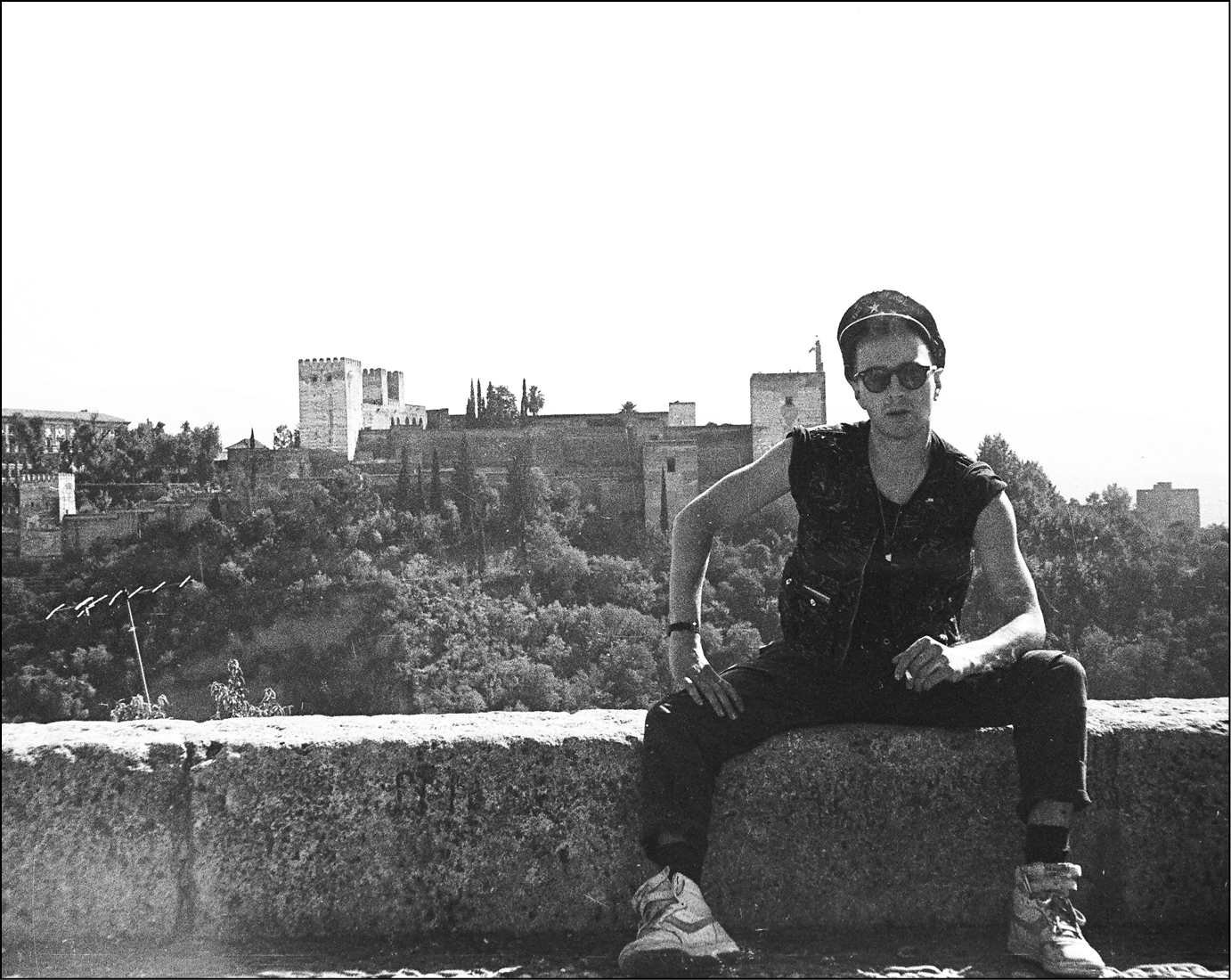

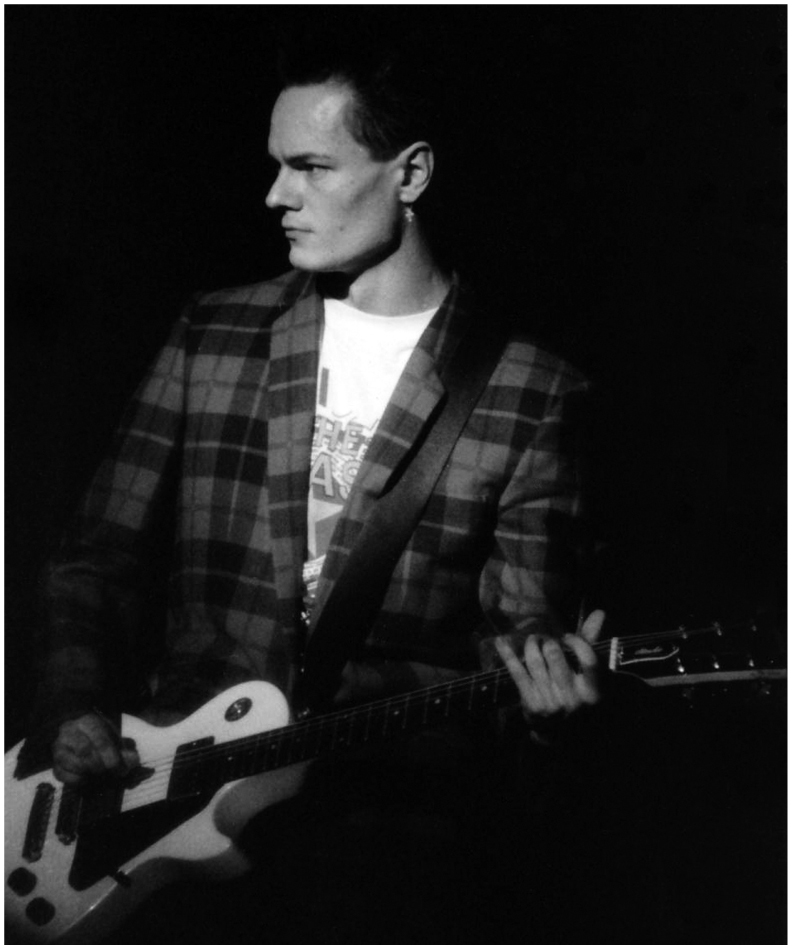

Joe Strummer in Granada, October 1984, wearing an Out of Control hat. (Photo by Juan Jesús Garcia.)

I’ve often lost myself,

in order to find the burn that keeps everything awake.

—Federico García Lorca

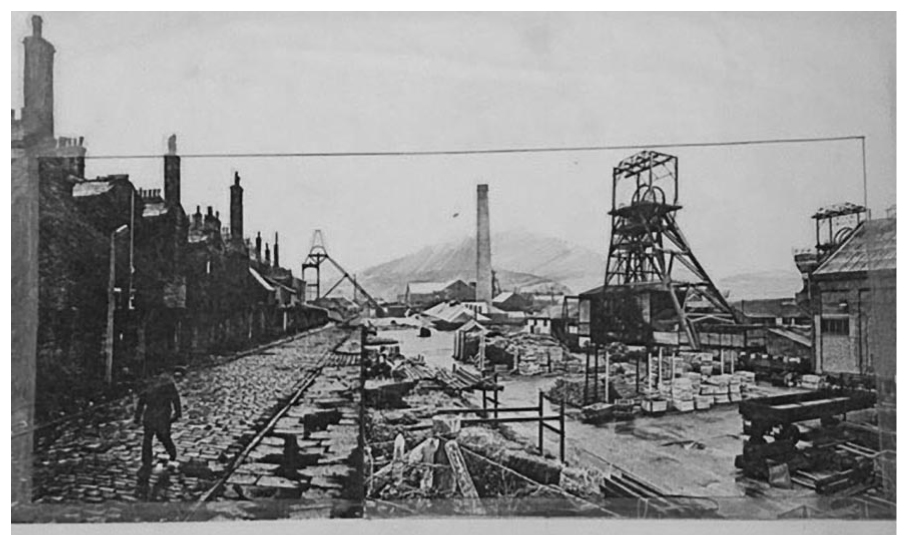

Women began organizing communal kitchens for the striking coal miners and their families driven by desperation and a realization that clubbing together makes food go further and sharing poverty makes it easier to bear. They devised ways to raise money to fund the soup kitchens and soon many became more politically active, joining the picket lines beside their male relations and friends.

—Alex Callincos and Mike Simons, The Great Strike, 1985

The man looked a bit rumpled, nursing a drink at a corner table in a bar in Granada, Spain. At first Jesús Arias didn’t recognize him: “The guy was dressed like a lumberjack in a checkered coat and dockworker’s hat. He was unshaven, unwashed . . . He looked like a hippie, really.”

It was early October 1984, and Arias had come to investigate an unlikely tale. The Spanish punk recalls, “My brother Antonio called me and said, ‘Hey, Jesús, yesterday we met Joe Strummer at Silbar. He is dirty and smelly but he will be there tonight again. Please come, we need someone who speaks English!’”

Startled, Arias pressed for more information. If anything, the details seemed even more incredible. “I came in and the bartender said, ‘This foreigner wants to show you his lyrics,’” Antonio told him. Puzzled, the younger Arias had gone over: “It was dark in the bar, I didn’t recognize him, he had a five-day-old beard and is showing me this small notebook with handwriting in English. I told him it was great but I’m really thinking, ‘How can I get away?’” Eventually, Antonio realized it was Strummer.

The elder Arias wasn’t convinced. Why would the lead singer of The Clash—a certified rock star—be skulking in a bar in Granada all by himself? Jesús explains, “There were rumors that Strummer had been around in the past, that he had a girlfriend from Granada, but no one I knew had ever seen him, and I was always skeptical.” Nevertheless, he went to see for himself.

Silbar was a hub for the small Granada punk community. Any vaguely avant-garde art had long been repressed in Spain under the dictatorship of General Francisco Franco, former ally of Hitler and Mussolini. Rock and other progressive scenes had sprouted in the space that developed after Franco’s death in 1975.

“All our friends, our bands—TNT, KGB, 091—went [to Silbar],” Jesús Arias says. “But Strummer? It didn’t make sense.” The Spaniard steeled himself, walked over to the table, and asked: “Are you Joe Strummer?” The man looked up from his glass and replied simply: “Yeah . . . What do you want to drink?”

When Arias answered, “Coca-Cola,” Strummer called out to the bartender in his ragged Spanish, “Hey, let me buy a Coca-Cola for this guy!” He turned back to Arias and asked, “Do you speak English?” “I told him, ‘Yes, I do, very badly,’” Arias laughs. “Joe said, ‘Well, that’s good enough for me!’”

Strummer proved to be an easy conversationalist and a good listener, but Arias could tell that not all was well: “At first, he was really happy and talkative. He liked Silbar and Granada, like it was a little London without all the critics. But soon you could tell he was really down, really sad. He was thinking all the time, crying all the time . . . He was drunk all the time.”

Strummer had first visited Granada in the 1970s with his longtime girlfriend, Paloma Romero. Better known as Palmolive, drummer for two trailblazing female punk groups, the Slits and the Raincoats, Romero was from nearby Málaga. In addition to being the inspiration for “Spanish Bombs,” she also introduced Strummer to another of his great loves: the art and life of Federico García Lorca.

Lorca was a leader of the “Generation of 1927,” a loosely aligned group of artists who brought avant-garde ideas into Spanish literature. An outspoken socialist, Lorca was also gay at a time when this was anything but accepted. Even so, his literary voice earned him a fervent following.

One scholar described the writer’s increasing depression, “a situation exacerbated by Lorca’s anguish over his homosexuality.” Other aspects of the poet’s life seemed familiar to Strummer: “Lorca felt he was trapped between the persona of the successful author, which he was forced to maintain in public, and the tortured, authentic self, which he could only acknowledge in private.”

After time in New York City, Lorca returned to Spain amid the growing tension that led to the Spanish Civil War. An attempted military coup against the elected leftist government soon led to civil war between Republicans—government supporters—and Nationalists under Franco’s command.

Lorca had every reason to fear for his life as summary executions and mass killings became common after war erupted in early 1936. Yet he remained in his home region of Andalusia only to be abducted and murdered by fascist forces on August 19, 1936. Tossed into a mass grave beside other victims of the terror, Lorca’s body was never found.

Lorca’s mix of politics, art, and anguish resonated with Strummer. At the time, going to Granada was—in the words of Chris Salewicz—“a bit of a pilgrimage . . . [Joe needed] to get away from things, he [needed] a creative place to think. He wanted to visit the grave of Federico García Lorca.”

Arias happened to be a student of Lorca’s work, and he bonded with Strummer during late-night talks about the martyred poet. Arias knew the area near Viznar—not far from Granada—where Lorca was probably killed, and the two made plans to visit. Before they could do so, however, Strummer disappeared just as suddenly as he had appeared—“like a ghost,” Arias says.

As this phantom flitted in and out of Granada, the miners’ strike was past the seven-month mark and nearing a turning point. In mid-August, Ian MacGregor sent a letter to the safety inspectors at the country’s coal mines. These “pit deputies” were not part of the NUM, but a smaller union with a long name: the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS). They had not joined the strike, though some refused to cross NUM picket lines.

That was expected of any union worker. Yet MacGregor found this unacceptable. If some miners themselves were now crossing the lines, why shouldn’t the pit deputies? He ordered all NACODS workers to cross picket lines or be fired.

This enraged the union. NACODS swiftly voted to go on strike, demanding that MacGregor’s letter be withdrawn, and also insisting that the National Coal Board agree to binding arbitration over any proposed future pit closure.

This course of action would be devastating to the government’s plans. By law, no mine could operate without safety inspectors; MacGregor’s ultimatum would effectively shut down all of Britain’s coal mines. Moreover, if arbitration became the last word on closures, the still-secret—and often denied—plan for relentless downsizing might well be stymied. Either way, this would hand victory to the battered but unbowed NUM. Feeling the heat, MacGregor scrambled to extricate himself from this self-created disaster by striving to delay the NACODS strike.

Thatcher once again had to prepare for desperate measures. Years later, the Guardian reported, “The secret list of ‘worst case’ options outlined to Thatcher by [her] most senior officials included power cuts and putting British industry on a ‘three-day week’—a phrase that evoked memories of Edward Heath’s humiliating 1974 defeat by the miners that brought down his government, and which must have sent a chill down Thatcher’s spine when she read it.”

The prime minister was adamant this must not happen. As a mid-October deadline for the NACODS strike approached, Thatcher applied immense pressure behind the scenes. Partisans in this conflict held their breath.

* * *

England in 1984 resembled a battleground. The United States, however, was victorious—at least if an advertisement that debuted in mid-September was to be believed.

“It’s morning again in America,” a white male voice intoned over soothing orchestral music. Familiar morning scenes of a boy delivering newspapers, a man on the way to work, a farmer on a tractor, slipped from one to another. The warm voice continued: “Today more people will go to work than ever before in our nation’s history, with interest rates at about half the record highs of 1980. Nearly 2,000 families today will buy new homes, more than at any time in the past four years. This afternoon, 6,500 young men and women will be married. And with inflation at just one-half of what is was four years ago, they can look forward with confidence to the future.” As wedding scenes melted into a vista of the US Capitol dome and American flags being raised, the narrator concluded: “It’s morning again in America—and under the leadership of President Reagan, our country is prouder, and stronger, and better. Why would we ever want to return to where we were only four short years ago?” One final image—a montage of Ronald Reagan and the American flag—remained on screen as the music faded.

The portrait the ad painted was powerful—but was it true? A tightening of the money supply actually initiated late in the Carter era by his Federal Reserve appointee, Paul Volcker, had led to the brutal recession of 1982. While devastating for many, it had driven down inflation and interest rates.

Only some reaped the benefits. For unlucky tens of millions, it was anything but morning in America. The ad ignored the ongoing agony of inner cities and Native American reservations, the record bankruptcies of family farms, and the growing ranks of the homeless adrift on American streets amid a widening gap between the rich and the poor. While the morning sunlight shone upon corporations shaking off regulations and taxes, the sun was setting on Rust Belt ghost towns.

This was reality. But did America actually want truth? Mondale had promised to “tell it like it is”—including that tax increases were inevitable—but had run headlong into the Reagan machine’s public-relations buzz saw.

The “Morning in America” ads—developed by a Madison Avenue dream team—were the first blow in a one-two punch that staggered Mondale. While Reagan himself stayed above the fray, his surrogates savaged the Democrat as a “tax-and-spend liberal.” “Mr. Mondale calls this promise to raise taxes an act of courage,” Vice President George Bush proclaimed. “But it wasn’t courage, it was just habit, because he is a gold-medal winner when it comes to increasing the tax burden of the American people.”

This rejoinder neatly evoked the recently concluded, hyperpatriotic Summer Olympics—boycotted by the Soviet Union and its allies amid Cold War tension—in delivering its hammer blow. It also twisted Mondale’s vow to not lie into something like an insatiable hunger to raise taxes. Outrageous, yes—but as the Democrat’s poll numbers dropped, it seemed America might want gauzy self-affirmation more than uncomfortable reality.

This was just as Reagan’s henchmen hoped. The retired actor was a master showman, and this was his “role of a lifetime,” as biographer Lou Cannon put it. Leslie Janka, Reagan’s deputy press secretary, admitted later, “This was a PR outfit that became president and took over the country. The Constitution forced them to do things like make a budget, run foreign policy, and all that, but their first, last, and overarching activity was public relations.”

The New York Times acknowledged this in an article on October 14, 1984, “The President and the Press,” which focused on how Reagan’s handlers sought to stage-manage their agenda by keeping national media outlets on a short leash. Even when the rare presidential press conference did happen, reporters were given little chance to ask real questions. When they did, Reagan turned on his folksy charm to skillfully evade inconvenient queries, smiling all the while.

The Reagan administration stymied the press in more muscular ways, such as by barring reporters from covering the US invasion of Grenada, an event that provoked little public outcry. According to the Times, “Many people outside the Government appeared to share the view expressed by Secretary of State George P. Shultz: ‘It seems as though the reporters are always against us. And so they’re always seeking to report something that’s going to screw things up.’”

Whether due to carrot or stick, many agreed. “Reagan had been one of the least scrutinized presidents in our nation’s history,” the Los Angeles Times opined. Perhaps it didn’t matter if the media had failed due to public indifference and administration manipulation, or had come “on bended knee,” kowtowing before the imperial presidency as critic Mark Hertsgaard argued. According to the New York Times, the result was the same: “The press has seldom been relegated to a more secondary role in determining the national agenda.”

* * *

Back in Camden, Sheppard, Howard, and White continued to bang away on their own. Simonon occasionally appeared, with Rhodes a more frequent but rarely friendly visitor. If the three hoped their strong performances under challenging conditions in Italy might lure their singer back to the fold, they were disappointed.

“Joe disappeared,” White says. “It made no difference to us seeing as we never saw much of him anyway.” Nonetheless, this time seemed different: “There was suddenly a lot of concern in the Clash camp about his whereabouts . . . He supposedly hadn’t told anyone where he’d gone.”

As worry rippled through the Clash ranks about a possible end to the band, White remembers, “Bernie told us that he’d broken up with Gaby and taken time away to sort himself out.” Salter later told White this was not true. The disgusted guitarist “no longer gave a fuck. I was sure that His Royal Highness would resurface when required.” Days turned to weeks and Strummer still didn’t appear.

Rhodes eventually delivered a sign that the singer was out there somewhere—tapes of what were supposed to be possible new songs. Their arrival hardly inspired joy, for as Sheppard recalls, “They were just raw chords and shouting, no lyrics, no melody . . . Terrible rubbish.” The three were somehow expected to polish these into something of worth.

The situation seemed absurd. White: “Bernie was very suspicious, very Stalinesque. It was all under wraps, just like top-secret information. I didn’t think too much about it at the time, but—looking back on it—it just seems insane.”

Sheppard agrees: “It started to get pretty nasty, pretty insecure. Attempts were made to explain what was going on, but they weren’t convincing.”

The trio put their backs into the task, but with dwindling hope. Sheppard explains, “The whole situation was very, very weird . . . It was if we had ceased to be a band of five people after our return from America.” Each day without new songs left them no closer to a studio, no closer to making the landmark record promised.

Yet the rump of what had been—and might someday once again be—The Clash soldiered on, hoping to make something of the creative chaos handed to them, and for the “platoon” to somehow be remobilized.

Meanwhile, the much-sought-after Strummer rematerialized in Granada some three weeks after his first visit. He resumed his friendship with Jesús Arias and the members of his brother Antonio’s band, 091, and made a new acquaintance, music journalist Juan Jesús García.

The two met in inimitable Strummer fashion. Arias: “Joe was so drunk he got lost in Granada. He ran into Juan Jesús García and told him, ‘I don’t know where my hotel is,’ so Juan Jesús took him there.” When a grateful Strummer offered García a gift in return for his kindness, the journalist asked for an interview.

“Joe said, ‘Okay—let’s meet at this place and time tomorrow,’” Arias recounts. “Juan Jesús thought Joe was so drunk he’d never remember but called me to translate in any case.” When Strummer did appear, the trio embarked on a wide-ranging conversation that gave tantalizing glimpses into the singer’s present thinking.

Wearing sunglasses and his Out of Control hat, Strummer spoke slowly and quietly, nursing a monstrous hangover. With Arias as go-between, García started off by asking why Strummer had come to Granada.

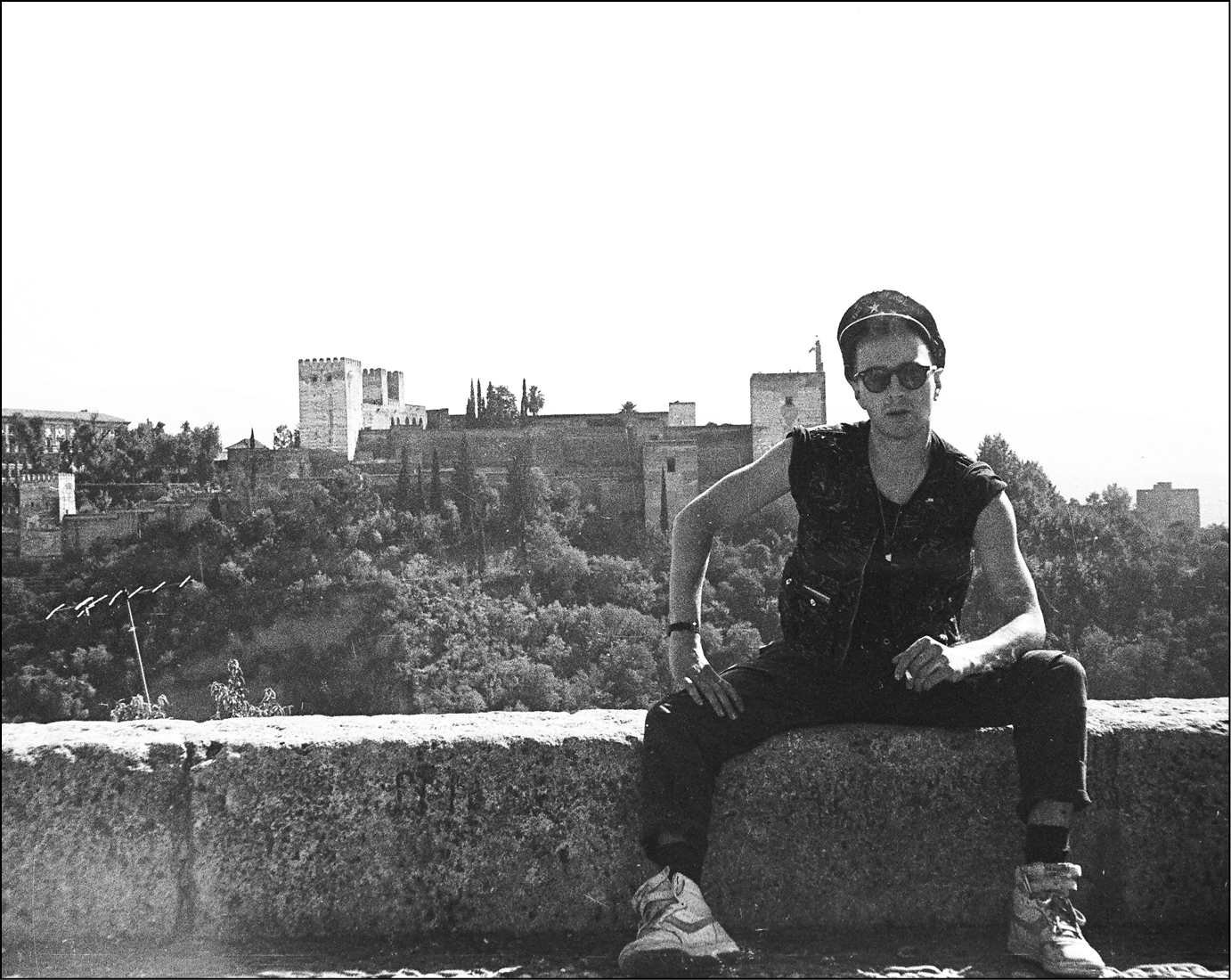

Juan Jesús Garcia, Jesús Arias, and Joe Strummer, Granada interview, October 1984. (Photo courtesy of Juan Jesús Garcia.)

Sipping his “hair of the dog”—carajillo, coffee with cognac—Strummer responded in a low, gravelly voice. “Obviously I am obsessed with Andalusia,” the singer said, then adding a second motivation: “The atmosphere in London is . . . depressing, depressed.” However, Strummer’s most important reason was “to think . . . I wanted to see things clearly, to be objective. I think I am getting there.”

Asked about the present situation of The Clash, the singer replied simply: “One of reconstruction.” After a brief pause, he elaborated a bit: “To learn from all the mistakes of the past and to understand. To feel the pain of all the mistakes of the past and so to do it better in the future.”

Pressed on the possibility of Jones returning to the band, Strummer held firm: “No, no. It will not be possible to be The Clash with Mick Jones. Because to be in The Clash, you must be able to self-criticize. And he doesn’t like to be criticized.”

García probed further, asking how The Clash kept credibility after the ejection of Jones and Headon. Strummer humbly responded, “I don’t know. I guess it’s because we have never tried to be anything but ourselves. We are what we are, nothing more. We don’t try to imitate an archetype or anything like that.” Turning to face the central critique of many current detractors head-on, Strummer asserted forcefully, “I don’t want The Clash to be a parody of ourselves!”

Evidence of deep soul-searching lay beneath Strummer’s words: “Above all, we have to be honest with ourselves, be able to self-criticize, to analyze ourselves. We have to play with the same passion before one spectator in an empty club as we do with thirty thousand in the audience. When people recognize this, they respect you. In this, we find The Clash’s credibility.”

Asked if The Clash’s political stance was unaltered, Strummer’s voice rose, immediate, emphatic: “Of course! I think the singer can be the madman outside of society, singing the truth. To be a singer you must live there always—always.”

A skeptical García pushed back, “How can you be outside the record business in a capitalist world? You have to be inside!”

Strummer granted the point, yet persisted: “Yes, but the record company can never dominate you, if you have independence, a position of strength . . . [At the US Festival] they asked us to play for half a million dollars. We agreed, and with that half-million you can say to the record company, ‘Don’t fuck with us’—that is independence.”

Shifting his angle, García then brought up attacks on The Clash by Crass and other newer punk bands. Strummer growled and launched a terse, enigmatic rejoinder: “These groups, they thought the game was . . . easy. They came for the game the way the animals come to the slaughterhouse.”

When García praised the way Sandinista! and Combat Rock utilized a vast array of musical forms such as jazz, reggae, funk, and blues, Strummer dissented: “No, it’s no good. There is no way that you can play better jazz than a jazz man. A jazz man plays jazz. The reggae man plays reggae. I am a rock man. I am not jazz or blues—I am a rock man, so now I will play rock.”

The singer then connected past mistakes with lessons for now: “We lost the idea of unity on [those records] but we learned what we should do in the future: it is best to stick to one approach that you grab ahold of and realize deeply. This is the difference between Combat Rock and the new record: Combat Rock was the sound of confusion; the new LP will be the sound of clarity. Mas duro—HARDER. But more clear, because no jazz, no reggae.”

Strummer suggested recording for the new record was imminent. While this would have been news to the rest of the band, García took it at face value and queried why he would come to Andalusia right before the sessions began. Strummer shot back, “I could not stand one more day in London!” adding wistfully, “I love Granada and I want to write songs for the new record here . . . Granada overwhelms me and gives me the peace necessary to write.”

When García queried about his progress, Strummer was ebullient: “I don’t want to boast, but I think it is the best writing of my life. The first days here I wasn’t getting anywhere when suddenly—flash flash flash—there were millions of images in my head. It was fantastic. I got into a bar, I stood at the bar and kept writing.”

Strummer’s enthusiasm seemed real, as Antonio Arias’s startling first meeting with him would suggest. But the weirdness of the encounter indicated something out of balance, as did the focus on words rather than music, given that the latter was the crux of Strummer’s creative dilemma.

The singer’s ever-changing mood also suggested it was all more complicated than he let on. At points, Strummer seemed almost schizophrenic. The happiness with his writing expressed to García contrasted with what he shared privately with Jesús Arias: “Joe would say, ‘I’m shit, man . . . I’ve done nothing with my life!’ I’d say, ‘What do you mean? You are Joe Strummer!’” Magnified by alcohol, the self-doubt shaded close to self-hatred.

When García tossed a softball question—“Do you like some new musical groups?”—Strummer remained silent. When pressed, he finally gave an answer that was, in his own words, “all around town”: “Before I had very fixed ideas. Now I am flexible, I know better than to be fixed. I want to be like the wind or water or trees or clouds; I want to understand everything. So, the answer is: I don’t know.”

When García pushed on this again, asking if Strummer was interested in popular new rock acts like the Pretenders or the Romantics, the singer responded obliquely: “I am interested in the eight directions.” A puzzled García followed up: “What are these?” Strummer: “When I know, I will tell you.”

“The eight directions” is a Hindu concept, used in this case apparently as his way of saying something like, I am adrift, with no direction home. So he was, for later in the interview, his “anti” stance of early 1984 reappeared. Ripping current music as “weak shit,” Strummer called for a new musical revolution to be made by the people just learning to play now: “Let’s go forward with the new generations!”

A sense of uncentered longing rose when Strummer discussed the nature of fame: “Once I was in strange countries with only a guitar and some shoes and nothing else. Once I have done this. I know there will be a time when I will live this life again. I am ready for this life. Success is good, but it doesn’t kill me to be the bum again.” If the return to this motif suggested an admirable humility, it fit uneasily with the reality of his wife and child waiting back in London.

The gap between Strummer’s aims and his ability to live them yawned ever wider. First, the Clash frontman movingly recalled his former musical partner: “Mick Jones and I were best friends, wrote all the songs together, shared the same passion for Andalusia and García Lorca. We had similar ideas about everything, I liked how he developed within the group, how he played guitar.”

But, he continued, “Mick started to think that he was a rock star, and didn’t like the self-criticism and self-examination that is part of The Clash. When the band started to get on the terrain of ‘we are the greatest,’ this was dangerous territory, where you can lose perspective on things. We lost the ability to communicate with each other, not just about musical differences. We didn’t understand each other as people. That’s why I told Mick to go.”

Finally, Strummer confirmed that part of the schism was related to drugs: “Mick went crazy with marijuana—all day, spliff after spliff. It was unbearable. Drugs are a waste of time that destroys people.”

This was essentially the antidrug stance Strummer had proclaimed across Europe and America for the first half of 1984. But Arias saw a darker side: “Joe was letting down his guard some by the time I met him. It could be funny, in a sad way. One night he was smoking joints, one after another. Then he tells me, ‘I fired Mick Jones because he was smoking too much joints.’” To Arias, Strummer seemed unaware of—or at least unable to overcome—the contradiction.

Sensing Strummer’s deep pain, Arias was sympathetic, but worried: “Behind the brave face, Joe was utterly lost.” Strummer told García and Arias he had come to Granada to “detoxify from England.” He had a curious way of doing this, marinating in alcohol, pot, and late nights, rarely shaving or bathing.

Rationalized by Strummer as an artistic catalyst or even a form of therapy, this “bum” lifestyle seemed more indicative of depression or addiction. Aware of this, the Clash frontman tried to not have too much alcohol during the interview, saying to a waitress offering a second carajillo, “No, one is enough. Lots of alcohol is for the nights, the day is for work . . . I have a lot of work to do right now.” Still, Arias rarely saw Strummer less than mildly drunk during this period.

The anguish seemed unending. When not expressed in drug use, it came out in tears. Arias: “We had been in the countryside and were coming back to the city when Joe suddenly sighed: ‘How wonderful it is to be to be alive!’ When I asked why he said this, he said: ‘I had a brother who committed suicide, I loved him. If he had come to Granada he would never have committed suicide!’ and started to cry.”

Arias: “I thought, ‘This man is very sensitive’—and he was—but he kept breaking into tears at other times too. Then I realized he had a lot of pressure on him, he was coming apart.” Strummer’s guilt was deep and apparent as well; Arias saw him withdraw five thousand dollars from a bank and give it to a beggar on the street.

The scenario was deeply poignant. Most likely, the singer needed medical help for his depression, grief counseling, maybe even alcohol/drug rehabilitation. Instead, Strummer embraced his pain—as a soul salve and creative aid—and then apparently ran from it into his substance abuse.

García came away impressed with Strummer’s humility and sincerity. Moreover, Diario de Granada—the local paper for which García wrote—had a genuine scoop. Much to his dismay, however, the article languished. Arias: “The editors didn’t think much of it, they didn’t know who Joe Strummer was, didn’t care. Finally, on a slow news day two or three weeks later, they said, ‘Okay, let’s publish this.’”

This, of course, was part of why Strummer had chosen to come to Granada. “Here he was nobody,” Arias says. “Joe told me, ‘Being in Spain is like being in Kenya,’ he could get drunk all the time and no one cared.” By the time the Diario de Granada article appeared on November 18, however, Strummer had returned home to face his distinctly non-bum life.

* * *

As Strummer was wrestling with his demons and his creative process in Spain, extraordinary drama had been playing out in the United Kingdom. An Irish Republican Army bomb aimed at Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet at a Conservative Party conference in Brighton missed her but killed five others. Emerging defiant and unscathed from the attack, Thatcher’s popularity rose.

Shortly thereafter, Thatcher pulled off another coup: by utilizing a spy in the labor union ranks and marshaling intense pressure, she was able to get the NACODS strike called off by the union leadership. Any hope of quick victory for the miners vanished with this decision, denounced as a “sellout” by Arthur Scargill.

As the Guardian later reported, “When [the NACODS strike] was called off, the relief in Downing Street was palpable: ‘The news was announced this afternoon and represents a massive blow to Scargill,’ read the ‘secret and personal’ daily coal report for Wednesday 24 October” that came to Thatcher’s desk.

The impact of this sudden reversal was immense. After that day, few neutral observers could see any obvious road to victory for the miners. In addition, the advance work on the legislative front was paying off, as judges were siding with Thatcher’s government against the union. As fines levied on Scargill and the NUM mounted, and control over union funds was taken over by the courts, the strikers were left even more bereft and impoverished.

Winter had once been seen as a possible savior of the strike, for increased heating demand might exhaust coal stocks and lead to power cuts, pressuring the government to give in. But coal supplies were still high, thanks to the careful stockpiling and the mines defying the strike in Nottinghamshire and beyond.

This left many miners among the only Britons lacking for warmth as frigid weather arrived. Some families began to scrounge for usable nuggets of coal from gigantic slag heaps. This was an exceedingly hazardous endeavor, and lives would be lost in the process.

As the police tightened their grip on the mining communities, violence flared. Union solidarity ran deep in these communities. More miners began to trickle back to work, and the struggle to enforce the strike became more intense. “A single scab brought a whole community onto the streets,” according to Callincos and Simons. As a result, villages could be “cut off from the rest of Britain for days while the police occupied it like a conquering army.”

Strummer was well acquainted with how vague laws against “sus”—“suspicious behavior”—were regularly used against nonwhite youth. He had often critiqued Britain’s police force as “fascist.” This bemused most white Britons, raised with the notion of the friendly neighborhood bobby. Now, however, the constabulary was becoming loathed in the mining towns as the brutal political pawns of Thatcher.

According to one village resident, “My kids now call the police ‘pigs.’ I didn’t teach them, they’ve learned it for themselves. I used to see it on the telly, kids in Northern Ireland treating police like this, and thought the parents must be to blame. But now, you don’t need to indoctrinate them. The police do it for them.”

Betty Cook of Women Against Pit Closures agreed: “We would read in the press before, say about a young black boy claiming he was beaten up by the police, and we would think, ‘He must have done something.’ The strike taught us better; we began to understand [other] people’s problems.”

Police officials reported to Thatcher that miners “frustrated by the failure of mass picketing are taking to ‘guerrilla warfare,’ based on intimidation of individuals and companies.” With the media largely under Tory control, this escalation—even if understandable—was likely to be self-defeating, as it reinforced Thatcher’s narrative of “union violence” that eroded broader support for the strike.

The miners saw no choice; they had to win the strike or face death as an industry. Feeling let down by their brothers and sisters in other unions—many of whom feared confrontation with the Tories, lest their own jobs be lost—the strikers turned to each other, with astonishing resolve. As Callincos and Simons detail, “Women began organizing communal kitchens for the striking miners and their families driven by desperation and a realization that clubbing together makes food go further and sharing poverty makes it easier to bear.”

While hardship mounted, these operations became essential for the strikers’ families shadowed by hunger. Rallying supporters across the land, the women “devised ways to raise money to fund the soup kitchens and soon many became more politically active, joining the picket lines beside their male relations and friends.”

For women like Cook, the strike also forced a reevaluation of roles previously unquestioned, as she bluntly told the Guardian in 2004: “During the strike, my eyes were opened and after it I divorced my husband. The strike taught me a lot, I had always been told I was stupid by my husband but I learned I wasn’t.” This newly awakened female power would be one of the strike’s lasting legacies.

Woman feeding a child at a soup kitchen for Cortonwood strikers’ families. (Photo © Martin Jenkinson.) Inset: Coal Not Dole button. (Courtesy of Mark Andersen.)

While the solidarity of the mining villages was being tested, so was that of The Clash. In photos taken by García in late October, Strummer’s dog tags were obvious—a sign that he recognized that somewhere the rest of his unit was waiting. How would Strummer bridge the growing gap? “He didn’t talk about the new band much,” Arias says. “I never saw him confident about them.”

Nonetheless, something seemed to shift for Strummer during his second visit to Granada. “I’ve often lost myself / in order to find the burn that keeps everything awake,” Lorca had written, describing something like the process that Strummer had used, first in Paris, then again in Granada, to try to find a way out of darkness.

If Strummer was unsure about his comrades, the new band was hardly feeling confident in him. Still mulling the mysterious tapes, Sheppard, White, and Howard now received their next gift: sheets of music with nothing but chord patterns.

While these seemed almost equally useless, the blow was softened—because Joe Strummer delivered them in person during a short visit to the practice space, his first in months. But was anything really resolved? Or had Strummer simply buckled under the immense pressure of manager and record company to return?

This turn of events marked Strummer’s reengagement with the band—though it would not be smooth. Strummer had intimated to García that the album would be out in February, suggesting recording was imminent. But The Clash’s leader had returned with tidings that were not entirely glad.

Strummer’s announcements were shared at a band meeting called at a Camden bar. The good news was that—after the latest three-month hiatus—The Clash would finally play live again: a pair of benefits for the miners’ strike at the Brixton Academy in early December, with rehearsals to commence shortly.

The singer still seemed out of sorts, and this news came off in an ugly way. Sheppard: “Joe sat us down and said, ‘Right, this is what we’re gonna do. We’re gonna play some benefits. It’s a good publicity stunt.’ I thought, ‘Why the fuck would you say that? That sounds really cynical and stupid.’”

The guitarist remains adamant: “I didn’t believe for a second we did those gigs to further our own career—keeping our heads down would have done that better. My response was, ‘I don’t care why you say we’re doing them; we are and about fucking time!’ If you’re gonna have politics, go do something, you know?”

White found Strummer’s latest pronouncement in sync with his own dark suspicions about the Clash mission: “My question mark over all of that, really, with Joe’s integrity, with regard to those kind of things—did he believe them or not, or was he just kind of using them as a tool? Did Joe really care about the miners, what was happening in England? I don’t know.”

Strummer’s confounding words suggested a continuing internal struggle with despair. White was feeling equally weary: “I didn’t care about miners or Thatcher or Scargill or working-class struggle or fucking anything else for that matter.” His lack of enthusiasm proved wise—for Strummer had another bombshell to drop, once he was sufficiently lubricated with alcohol.

White: “We’re drinking cognac at lunchtime. Then on to beer and by three in the afternoon, Joe drunkenly informs me that Nick and I aren’t good enough to play on the forthcoming Clash record.” After all the touring and other work to build a powerful new Clash—labor that was clearly paying off, as the live shows proved—this sudden reversal seemed to make no sense at all.

Years later, White shrugged it off: “Nothing Joe or Bernie said seemed to have a basis in reality anymore. Things just changed from one day to the next, from one beer to the next . . . It was depressing.” Sheppard agrees: “At the same time as the benefit news, it was presented to me and Vince that we wouldn’t be on the record, and that we would be sent off to make some other record with somebody else . . . [It was] just more nonsense stuff.”

Rhodes’s destructive hand is apparent in this turn of events. The Baker doesn’t hesitate to point the finger: “Joe’s hesitation and lack of direction at the end can surely be attributed to Bernie’s constant haranguing tirades and self-defeating windups.”

What could be the aim of such tactics? Rhodes faced his own set of pressures, not least from their ostensible employer. As Vinyl points out, “Bernard had an ally in Paul Russell of CBS UK, the part of the company we had technically signed on with . . . He respected The Clash were unlike any other band.”

Yet there was a financial reality involved as well as an artistic one. Vinyl: “The Clash was one of the few big sellers for CBS UK, it was a feather in their cap, so a lot was riding on a strong follow-up to Combat Rock.”

This band of headstrong would-be revolutionaries was no record executive’s dream outfit. “At the outset, The Clash was a hard sell,” admits Vinyl. “But as soon as it isn’t a hard sell, it becomes a hard sell again, do you know what I mean? Russell was like, ‘We gave you the space, now where are the goods?’”

The weight was onerous even for the hard-boiled Rhodes. But it was not the only factor motivating his relentless push on Strummer. The record could indeed have been banged out long ago, per the singer’s often repeated preferences.

Rhodes had another agenda that was not so open: the new album’s musical direction. This was driven by an artistic intuition that The Clash must move forward, not back. Despite Strummer’s repeated dismissals, Rhodes felt that any leap toward the future had to incorporate elements of the new electro-pop style.

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that this echoed the view of the banished Jones. While he had dropped both Headon—still lost in addiction—and the idea of launching another Clash, he had a new band: Big Audio Dynamite, a.k.a. BAD. By early October, the band—which emphasized the hip-hop and electronic elements that had sown such divisions in The Clash—was playing out to good reviews, including opening twice for the Alarm in the north of England.

Such moves by his nemesis would inevitably worry Rhodes and possibly Strummer as well. Rhodes likely viewed the new record as a way to respond to Jones by keeping the punk edge but adding “modern” touches.

How was this to be done, who would do it? Given that no one in the present Clash had been recruited with this in mind, and neither Strummer nor Simonon evidenced any interest or proclivity for this, it was unclear.

Rhodes’s way with his platoon made this more difficult. In Granada, Strummer had touted the benefits of “self-criticism,” urging “all musical groups in Spain and the world to self-criticize—this is the most important thing.” That amounted to an endorsement of the approach that Rhodes had imposed on the band since its beginning, against which Jones had rebelled.

But if self-criticism in principle made sense, in practice it was often abused. Even as ardent a practitioner as Bernardine Dohrn of the Weather Underground admitted that the results were often “terrible.” In the wrong hands—as often in Communist China and, it seems, in The Clash—this tool for democracy and growth could easily become cover for authoritarianism.

* * *

As The Clash prepared for its return to live action, America had gone to the polls. With economic conditions improving for many, and his campaign ads laying waste to Mondale, Reagan soundly thrashed his opponent, winning 59 percent of vote, and nearly all the electoral college tally. Mondale won only Minnesota—his home state—and the District of Columbia.

It indeed appeared to be morning for the Reagan forces, if not for the country. This triumphant second election seemed to signify a genuine mandate for the president to consolidate and complete his conservative counterrevolution.

The greatest victor, however, might be seen as apathy, for barely more than half of eligible voters exercised that right. Many of those opting out were low-income citizens who had the most to lose from a second Reagan term. They believed their votes didn’t matter, pollsters reported, that the system was rigged. While not entirely untrue, their absence helped preserve that unhappy status quo.

Jesse Carpenter was one of those who saw the election as a circus. Carpenter had been awarded the Bronze Star as an Army private in 1944 for carrying wounded soldiers to an aid station in Brittany, France, under “unabated enemy fire,” according to his medal award certificate.

Carpenter had returned home damaged. Slipping first into alcoholism and then homelessness, he now navigated DC’s streets with his wheelchair-bound best friend, John Lamm. On the night of December 4, the pair came to sleep in Lafayette Park, across the street from the White House. Not long after dawn, US Park Police found Carpenter lying at the feet of his friend’s wheelchair. He had frozen to death across the street from the presidential mansion.

The Community for Creative Nonviolence (CCNV)—a direct-action outfit that stood with DC’s homeless—had befriended Carpenter and Lamm. After his death, they won Carpenter the right to a hero’s burial at Arlington Cemetery. “He avoided death abroad to die on the streets here,” said the Reverend Vin Harwell, presiding over the funeral. “His is a story of tragedy, a life disrupted by war, never to fully recover. It is also a story of national tragedy, because this is a nation where millions of Jesse Carpenters are homeless and without help.”

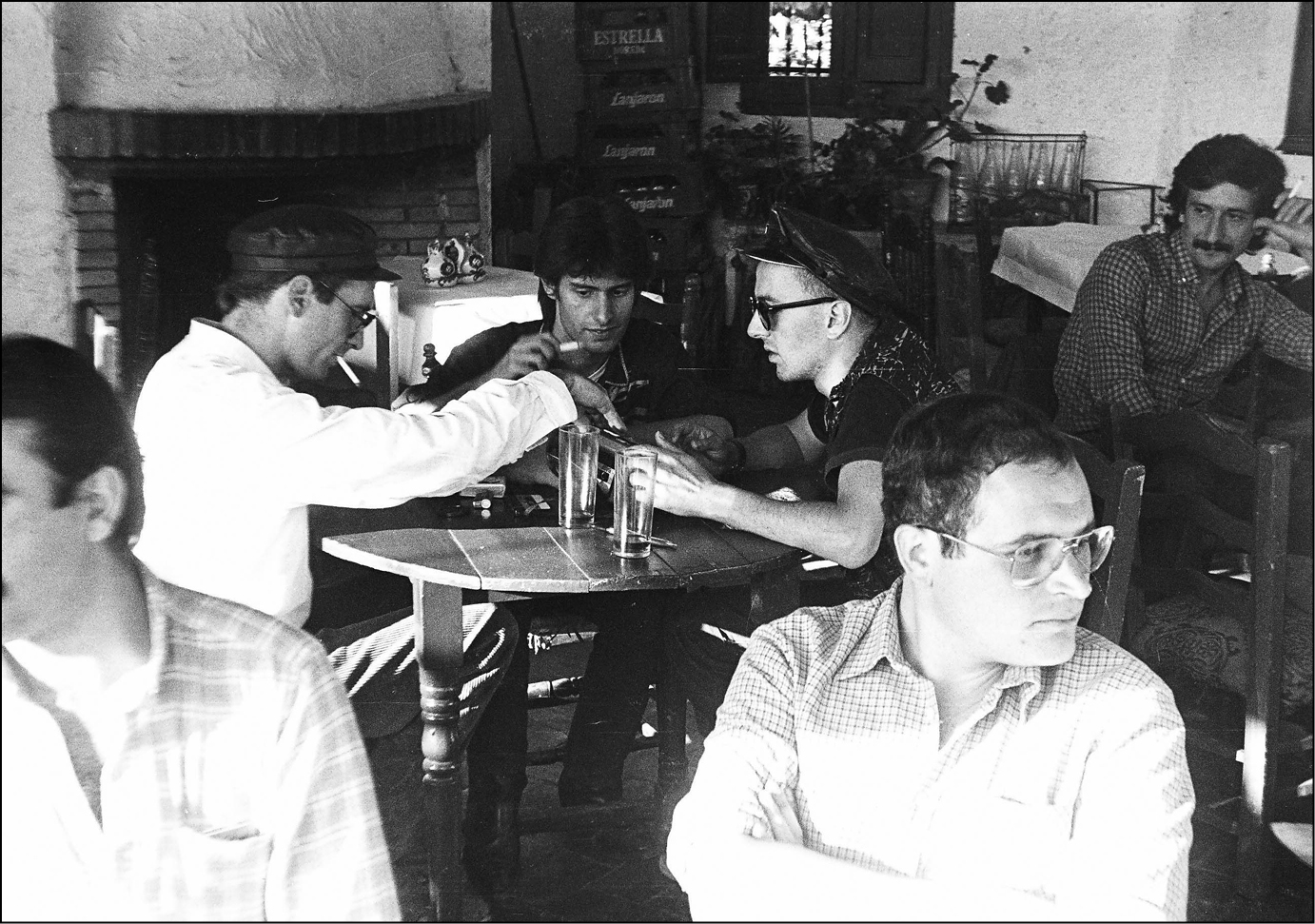

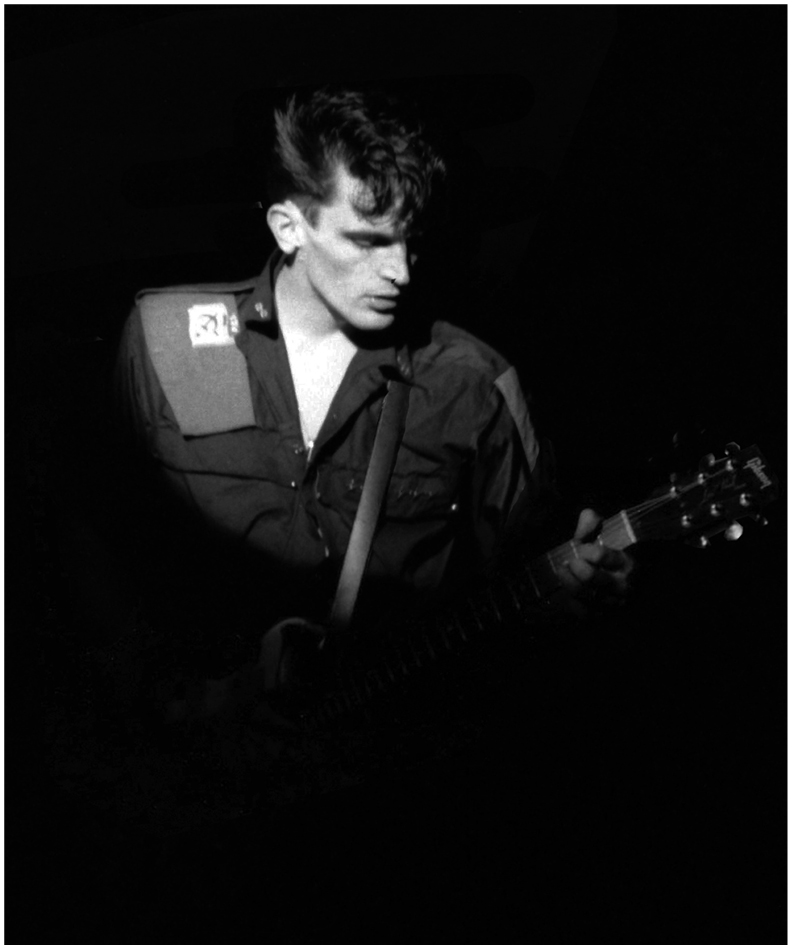

“Outright outright dynamite / this is the one for the miners’ strike.” Joe Strummer in front of mining village backdrop, Dec. 6, 1984. (Photo by Per-Åke Wärn.)

Nick Sheppard. (Photo by Per-Åke Wärn.)

Vince White. (Photo by Per-Åke Wärn.)

Paul Simonon. (Photo by Per-Åke Wärn.)

Joe Strummer. (Photo by Per-Åke Wärn.)

Billboard for the miners’ show. (Design by Eddie King.)

Draft designs for buttons and posters. (Design by Eddie King.)

Tickets to the miners’ show. (Design by Eddie King.)

Montage of mining villages for stage backdrop. (Design by Eddie King.)

Bunting and stencil designs. (Design by Eddie King.)

Button design. (Design by Eddie King.)

Carpenter’s unnecessary death was an indictment of a country grown cold and complacent. When Strummer visited DC in April 1984 on tour, he encountered homeless people sleeping on the street mere blocks from the White House. “What is Reagan doing for people like these?” he growled to a reporter, with the answer self-evident.

This might seem unfair. Only days before the election, Reagan had agreed to turn a dilapidated federal building near the US Capitol into a model shelter for more than a thousand men and women. This act of generosity, however, only came after one of CCNV’s leaders, Mitch Snyder, embarked on a water-only fast that left him near death. It took fifty-one days and an election-eve appearance by a gaunt Snyder on top-ranking TV news show 60 Minutes before Reagan relented.

Despite the actions of CCNV and its allies, the death of Jesse Carpenter made hardly a ripple across most of America. Yet only five days before, another tragic death—this one across the ocean, on a road near Rhymney in South Wales—would have a dramatic impact on the fate of a nation.

Support for the strike in South Wales had been so broad that the area had hardly seen any mass pickets. They weren’t needed. As the strike neared the nine-month mark with desperation and deprivation growing, however, a few broke down and returned to work. Community anger over such “scabs” was intense, leading to daily confrontations as the returning miners sought to go to their pits.

On November 30, taxi driver David Wilkie was taking a strikebreaker to the Merthyr Vale mine under police escort, as he had done numerous times before. But this time, two strikers were lying in wait to drop a fifty-pound concrete block from an overpass onto the cab. The block crashed through the roof of the Ford Cortina, instantly killing Wilkie and injuring his rider.

The national revulsion over the killing was immediate and near unanimous, damaging support for the strike even among union partisans. Wilkie was not the first person to die—miners David Jones and Joe Green had been killed while picketing, and three children died scavenging coal—but his death came at a crucial moment, turning public opinion sharply against the strike.

Gloom spread across the mining communities. With Christmas coming, no money to pay for presents, and precious little good cheer to share, many die-hard union men had to make heartrending choices. Allen Gascoyne, NUM branch secretary in Derbyshire, remembers, “I had a guy come to me at Christmas in tears. He was losing his house. His wife was going to go, he’d got all these debts. I said: ‘We’ve lost, kid, so get back to work.’”

Despite this advice, Gascoyne himself stayed out on strike, as did most miners, determined to hang on till the bitter end.

Such was the situation as The Clash prepared to mount the Brixton Academy stage to stand with the miners. Skeptics saw the band as a latecomer to the struggle. “Better late than never,” Sheppard tersely countered. Commencing its first full rehearsals in nearly half a year, the new Clash threw itself into preparing for possibly their most consequential gig ever.

The Academy was putting itself on the line by hosting an event dubbed “Arthur Scargill’s Christmas Party.” As Simon Parkes recalls, “Established venues such as the Albert Hall and the Hammersmith Odeon wouldn’t touch this gig with a ten-meter pick handle. The last thing they wanted was several thousand angry, hyped-up miners led by, horror of horrors, a punk band.” Left unmentioned was the possibility of retaliation by a government that was always watching.

Nonetheless, both band and venue fully committed to the show. Long frustrated by The Clash’s inaction, Eddie King was overjoyed to be stepping forward at last: “The police had cut off entire communities, beat up anyone trying to get to them, the government had effectively declared war on parts of its own country, its own populace . . . Everyone wanted to do something for the miners!”

King knew the score: “Thatcher had destroyed the entire industrial infrastructure, ripped out the heart of the country. Scargill and the miners were the only viable opposition. It was basically civil war—Thatcher stopped their benefits, seized the union funds, you got thousands and thousands of families without food or heating for their houses, kids dying scuffling for coal scraps.

“I was on retainer at that time, so only got paid a set amount,” King continues, “but I went above and beyond because it was something we all really wanted to do.” He designed T-shirts, buttons, banners, stencils—“even yards and yards of bunting!” he laughs—all featuring a miner juxtaposed with the Clash star.

The artist also created a special stage backdrop. King: “It was a massive collage of mining villages, I got photos and blew them up, put them together by hand, it took days and days of work. It was a labor of love.” The result was stunning. “It was like a carnival at the Academy with pictures of miners everywhere!”

The upbeat vibe was needed. Asked by García in late October if he wanted to talk about politics or Margaret Thatcher, Strummer had let the question hang in the air for a few telling moments before offering a quiet “No.” If this suggested despair about the momentum of events, it surely did not mean an absence of concern. Indeed, as the band practiced for the Brixton miners’ shows, Strummer brought three nearly finished songs for the band to learn.

One spoke directly to the agony of the miners’ strike. Sheppard: “‘North and South’ was brought to the rehearsals, and we worked that out quickly as a band, along with the two others. The idea was that I would sing it together with Joe.”

“North and South” was an arresting tune, underpinned by terse, melodic guitar. Its lyrics mourned the gap between a northern England suffering the worst economic conditions since the Great Depression and a prosperous south reaping the benefits of Thatcher’s financial initiatives. Focusing on “a woman and a man / trying to feed their child / without a coin in their hand,” the song asked poignantly, “Have you no use / for eight million hands / and the power of youth?”

As unemployment rolls stretched toward four million, with youth joblessness at a scandalous level, this was no idle question. The song was perhaps Strummer’s apology for six months of paralysis, and a vow that it was ending: “Now I know / that time can march / on its charging feet / And now I know / words are only cheap.”

The song showed Strummer was well aware of the desperation growing in the mining communities. Admittedly, playing a benefit concert was of limited use. As such events had multiplied over the past few months, constituting a significant form of support for the strike, skeptical voices like Callincos and Simons asked how “a few rock concerts would cow a government which respects only power, and which had shown itself absolutely determined to crush the miners?”

In part, they were correct—music alone could not hope to stop Thatcher. But to agree that concerts alone are insufficient is not the same as conceding they have no value. At this moment, just when everything seemed to be turning against the miners, having the single most popular punk band in the country take their side was no small matter. Beyond the financial boost—“Having The Clash play for you could raise something like a small country’s GDP!” argued King—there was the power of moral support, a precious bit of light amid the growing darkness.

Would it have made a difference if the band had engaged six months earlier, had toured the UK then, supporting the strike? Vinyl would later argue, “Tours take time to set up . . . Remember, this is a big band, everything will be under the microscope, you can’t just play.” Yet The Clash had rarely been stopped by such calculations—part of why the band meant so much to so many.

Even a fan as demanding as Billy Bragg would later concede, “It wouldn’t have made the difference.” But as The Clash took to the stage on December 6, 1984, it came bearing the frustration, anger, and pain built up over months of agonizing inaction amid the UK’s ugliest, most consequential political face-off in decades.

Diverging from past set lists, White and Sheppard kicked it off with a rarely heard Sandinista! chestnut, “One More Time,” standing on their own before five thousand roaring fans. White: “I opened the song with something original I invented and let it howl out with feedback. It was moody and heavy and different. I had my own style now and was going to let it show.”

As White released his jagged guitar pattern, Sheppard met it with his own attack. Prowling the stage, the guitarists staked their claim to the song. Sheppard’s guitar dropped away, leaving space for White’s short interlude of reggae “chop” chords. This reverie ended suddenly, the duo generating a dissonant maelstrom.

When the guitars pulled back again, first Howard and then Simonon entered the fray, drums and bass punctuating the guitar squall. Finally, Strummer strode onstage, dressed all in white, with a black leather jacket and shades, and the crowd erupted. Hanging back as crisp reggae “chucks” bounced off crashing punk power chords, he let the tension build, as with the extended versions of “London Calling” in Italy.

Finally, Strummer stepped forward. Grabbing the mic, he chanted, “Outright outright dynamite / this is the one for the miners’ strike,” over and over. The song was a blistering denunciation of poverty and racism, channeling echoes from the American civil right movement and urban riots. As the tune settled into its familiar groove, the Clash frontman ripped out the song’s opening lines, adjusted to fit the moment: “Must I get a witness / for all this brutality? / Yeah, there is a need, brother / you don’t see it on TV!”

As in Italy, few would have guessed that both guitarists had largely crafted this radical rearrangement of the song, with Strummer working out his ad libs during the sound check. All the hours of work as a trio were paying off now. Sheppard: “We just took it and ran with it, basically. We’d been playing a lot together, and we had got very tight. We knew each other’s vibe.”

The reworked song demonstrated the power of the new Clash. While Strummer exhorted the crowd, “All together now / push!” the music dropped away, leaving only Simonon’s bass. Then Strummer leaped back in, quoting Lee Dorsey’s R&B hit “Working in the Coal Mine” over the spare pulse. After one final “down, down / working in the coal mine,” both guitars reignited, followed by the rhythm section, launching the song toward its climax.

As the music slowed, everyone dropped away, leaving White’s clipped chords on their own, walking the tune to its end—only to have Strummer slash through the lull, screaming, “London’s burning!” Shifting effortlessly from dub to full-throated punk roar, the band was off into a Clash classic not played live in years.

Strummer ranted over tightly wound chaos as the band drove the song to its clamorous conclusion. With feedback still hanging in the air, Howard tapped out the intro to “Complete Control.” Again the band was off, seamlessly going from one tune to the next. No recent Clash set had begun with such kinetic energy.

When the band finally paused, a delighted Strummer came to the stage’s edge. Shading his eyes to survey the crowd, he called, “I forgot to say good evening!” The audience roared, and the singer went on: “We all know why we’re here so I ain’t going to go on about it. However, without meaning to disappoint, we asked Arthur to do ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ with us . . . However, he said he forgot the words and his wig doesn’t go into a quiff anyway!”

His good-humored shout-out to the miners’ leader completed, Strummer turned to the band and announced, “This is Radio Clash!” The song’s spring-tight rebel funk was a breather from the breakneck pace, and the message underlined the band’s mission tonight: to be an alternative source of information, helping to build a community of resistance to Tory rule.

A tip of the hat to Strummer’s recent sojourns might be seen in the subsequent song, “Spanish Bombs.” A sharp new guitar line opened the tune and then reappeared near the end, again showing that the band remained able to shape the older material to good effect. A spirited Strummer then paused to tout the American hip-hop group Run-DMC, as a parable of hope and despair in 1984.

“The other side of the coin is appearing,” the singer asserted. “Look out the window and you have got Duran Duran and Wham! and Margaret Thatcher . . . the Daily Mail and the Daily Telegraph . . .” As his soliloquy faded, the singer grabbed his head and moaned: “Sometimes I can’t see the light . . .”

Perhaps this was an indirect comment on the darkness of his past months. If so, the cloud was wiped away in an instant: “But when I hear Run-DMC can draw forty thousand people in Detroit, then I seem to think: ‘Have no fear, señor!’” The singer’s buoyant mood lifted “Rock the Casbah,” “North and South,” and “Are You Ready for War?” A substandard new song, “Fingerpoppin’,” then slowed the momentum. A clumsy comment on club mating rituals, the tune sounded flat and unfinished.

This would be the evening’s last misstep. Strummer switched to bass to allow Simomon to lead the band in another rarely heard number, “What’s My Name.” While Simonon’s limited voice had not suited “Police on My Back,” it meshed well with this relentless tale of urban anonymity and gutter-punk grit. “The Dictator” followed, with lyrics rewritten to indict Thatcher and her “shock troops.”

The song was played fast and hard, leading powerfully into yet another back-catalog barn burner, “Capitol Radio,” decrying a media monopoly meant to “keep you in your place.” Next the band downshifted to a moody “Broadway,” whose introspection quickly gave way to the guitar explosions of “Tommy Gun,” punctuated by Howard’s double-time drum “machine gun” fire.

When the band paused, Strummer returned to a founding theme, introducing a revived “We Are The Clash” by pointedly noting, “When I say, ‘We are The Clash,’ I am talking about considerably more than five people.” Tonight’s version restored the “we can strike a match / if you spill the gasoline” couplet to the chorus.

As if to underline this idea, the band next crashed into a version of “Career Opportunities” that pitted the usual roar of its chorus with a spare dub take on the verses, opening space for a massive sing-along. As the crowd picked up this challenge, someone mounted the stage, grabbed a mic, and screamed, “Revolution, revolution!” before melting away into the masses.

“Revolution” was surely a lofty aim, especially at this moment in British history. Nonetheless, the cry communicated the mood at the Brixton Academy as the musicians exited, audience adulation ringing in their ears.

The band returned for two encores, the final one consisting of potent new number “Dirty Punk,” “Jericho,” and a slam-bang “This Is England,” further developed and sped up from its Italian version and—inexplicably—missing its last verse. Strummer then introduced “an English folk ballad”—“White Riot”—that gained resonance from the fact that miners brutalized in the bloody Orgreave ambush now awaited trial on charges of “riot” that might mean life in prison.

Then the night was done. Despite the agonizing delays, the internal chaos, and Strummer’s depression-verging-on-collapse, The Clash had risen up to give a performance for the ages. Moreover, nearly half of the set—nine songs in all—were unreleased, and included two sharp new ones. Even Chris Salewicz—no easy sell—had to admit the show was “fantastic.”

The next evening was again packed. Simon Proudman, who had seen the new Clash in Bristol in February, later recalled the night’s spirit: “There was huge excitement in the streets outside the Academy, this was the gig everyone wanted to see, and [we felt] The Clash were not going to disappoint us.”

If some of the festive decorations had gone missing—“The punters stole them!” says an amused King—energy crackled in the air. UK reggae star Smiley Culture stepped to the mic to introduce the band: “For those of you who were here last night, it was wicked . . . Show them how much you love them . . . The Clash!” With that, White and Sheppard strode onstage.

This show was not as charmed as the previous evening. As White went to ignite “One More Time,” his guitar malfunctioned. Frustrated, he stalked offstage, leaving a startled Sheppard to improvise. “I started playing a bit of the James Bond theme,” the guitarist laughs. “Joe looked at me like I was crazy.”

Despite the tricky start, Sheppard deftly brought the song around. White’s instrument was fixed swiftly and he rejoined the storm of guitars, bass, and drums. Then Strummer lunged forward, even more emphatic than the night before: “I GOT TO GET A WITNESS / FOR ALL THIS BRUTALITY,” he howled as the band accelerated. “YOU KNOW WE GOT A NEED TO, BROTHER / WE DON’T SEE IT ON THE TV!” Featuring a looser, spacier feel, this version of “One More Time” was almost as powerful as the previous night’s rendition.

The downs and ups of the opening song foreshadowed the evening. While the band followed the earlier night’s set list closely—excising only “Fingerpoppin’,” replaced by a chaotic take on “Brand New Cadillac”—technical glitches popped up here and there, and the band appeared a bit off at times. Regardless, the show was still powerful, and the crowd response fervent.

Standing still was rarely an option at Clash gigs, and this night was no exception. Proudman recalled the thrill of being “in the middle of a crush of a crowd moving backward and forward in excitement to the songs they loved. The band seemed to be enjoying it as much as the crowd. There was no Mick Jones, but no one in the audience cared as [we] shouted [our]selves hoarse.”

Strummer paused during the show to acknowledge the question on many minds. After thanking opening acts Restless and Smiley Culture for “putting your money where your mouth is,” Strummer had “another word as to the future: it’s been two years since we made a record. Has anybody noticed that?”

When the crowd roared, the singer continued: “Yeah, me too. The fact is, we were waiting to see what was going to happen, we have to wait for things to go by. We’ve got a record, we’re going to put it out in the new year, and we’re going to be back.” As the audience cheered again, Strummer raised his voice—and the stakes—even higher, yelling out, “We’re going to make a comeback!” as the band launched into “Spanish Bombs.”

While the words were passionate, they hardly reflected what had transpired over the past six months. Nor did they exactly speak the truth about the as-yet-unrecorded new album. As the band would soon discover, there can be a world of difference between having the songs for a new record and actually making it.

Yet picking up The Clash’s fallen banner was clearly on Strummer’s mind. After a surprise third encore sprang “Safe European Home” and “London Calling” on a startled audience already exiting the hall, Strummer called out one last time: “Great to see you here—we’re coming back and better! Take a note, lads . . .”

While “London Calling” faded into the night, Strummer’s words sent the crowd home with a promise and a mission. For two nights, this new Clash had gone back to war, a righteous burst of passion and artistry as 1984 drew to a close.

Now a powerful new album seemed within their grasp. Here was a chance to redeem the resurrected Clash; such art could touch hearts and minds, and maybe even help turn the world.

“I want you to show them how much you love them, because they are not going to be here tomorrow night, or the night after, here again,” Smiley Culture had proclaimed on that second night at Brixton Academy, urging the crowd to “keep on calling them, man—The Clash, The Clash!”

This intro held more truth than Culture knew. In 1985, there would be a new record and live shows . . . but never again would The Clash play its hometown.