Issunbōshi (The One-Inch Boy)

MY SMALL DAUGHTER was playing with her friend. They had built a beautiful blockhouse and all they needed now was a one-inch boy.

“I wish we had a live one,” sighed my little girl. “We could take him around in our pockets and play with him.”

I said, “He might find it uncomfortable. Besides, who would like to be as small as that? You know, even the One-Inch Boy grew up into a fine young man.”

“Did he? Please tell us the story about him.”

I looked at my watch—as grownups do—and decided there was just time enough to tell it.

So my daughter nestled up on one knee and her friend on the other. I leaned back and felt their warm sweetness against me. I closed my eyes and was soon far off in wonderland.

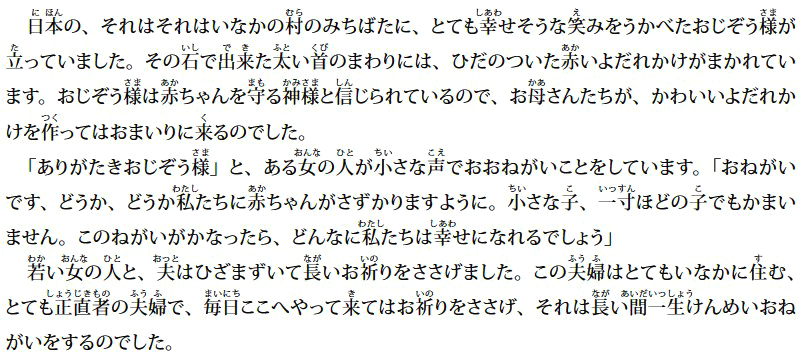

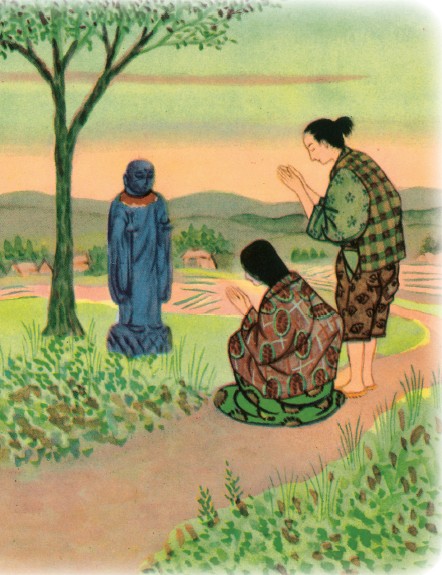

In the deep country of Japan stood a wayside statue of happy looking Ojizō-san. Around his thick stone neck he wore a frilly red bib. Ojizō-san is the god who looks after Japanese babies, so mothers make pretty bibs for him to wear.

“Please, most honored Ojizō-san,” said a woman’s soft voice, “Please, we would so much like to have a baby of our own. A tiny little fellow—even as small as an inch. It would make us so happy.”

A young woman and her husband knelt there in deep prayer. The couple were good, simple, country folk. They came every day and prayed and wished very hard for a long long time.

At last, to their delight, a little boy was born to them. But he was a very, very small fellow, smaller than a baby’s chopsticks. However, the couple was pleased and laughed happily about the size of their new baby.

Very soon he was no baby at all. Year by year he grew older but still no bigger, so his parents named him Issunbōshi, which means One-Inch boy.

When he went out on the street the other boys would come running and shout, “Oi, Oi! Here comes the little one. Look out, clumsy! There he is under your feet. Don’t step on him!”

The rough boys would boast, “I can pick him up between my thumb and finger and crush him to death. Hello, peanut! Hello, toothpick! Now, where oh where can you be!”

You may be sure Issunbōshi didn’t like this but he always kept quiet and just smiled pleasantly.

Well as the days and months passed, Issunbōshi grew tired of everything. He was tired of getting up every morning to eat from his doll china bowl and nutshell. He was tired of being teased by great big boys. He was tired of sleeping on his handkerchief-sized Japanese futon. He wanted to venture out to seek his own fortune.

His parents were anxious for him. But they looked around and presently his father picked up a sharp glistening needle from his mother’s workbox, and his mother picked up his father’s big red lacquer soup bowl with his ivory chopsticks.

Issunbōshi girded the needle around his waist and there it hung against him, looking sharper than a sword. And, carrying the red lacquer bowl and chopsticks, he went as far as the beach of Sumiyoshi, accompanied by his father and mother.

When he got there, he turned to them and, bowing very politely, said, “Otōsan, Okāsan, itte mairimasu. I am going.”

“Take good care of yourself,” they cried. “You have the world before you.”

“Indeed I have!” said Issunbōshi happily. “You wait—I will surely succeed.”

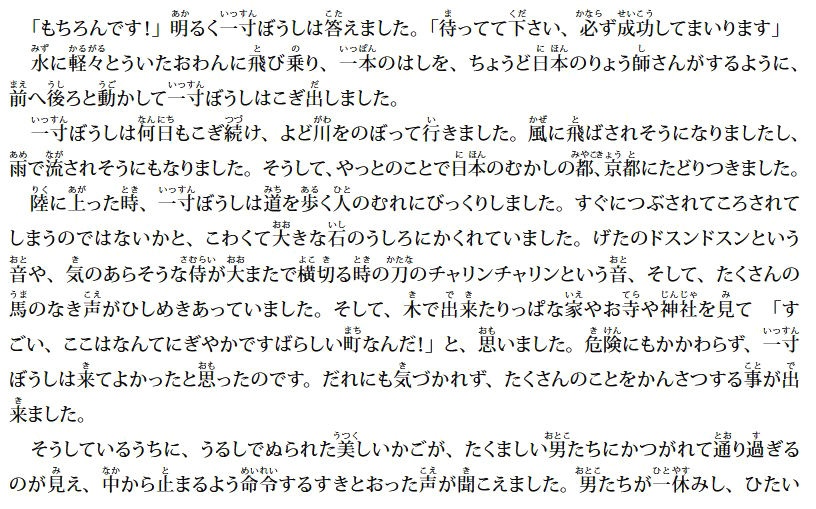

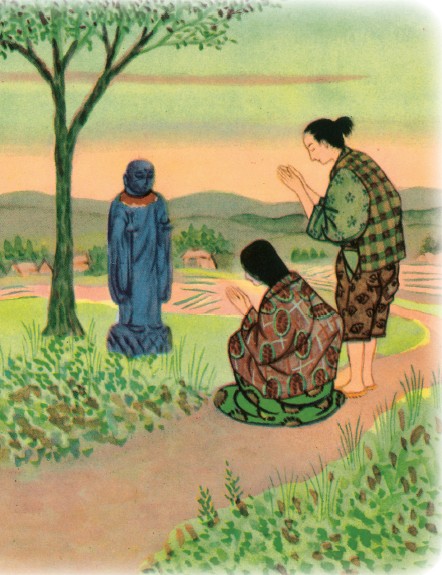

He jumped into the bowl, which floated well on water, and began rowing with one of the chopsticks—back and forth, back and forth—just as Japanese fishermen do.

Issunbōshi rowed for days and days up the Yodo River. He met with wind that nearly toppled him over and rain that came with rushing water. Somehow or other, he finally succeeded in reaching Kyōto, the old capital of Japan.

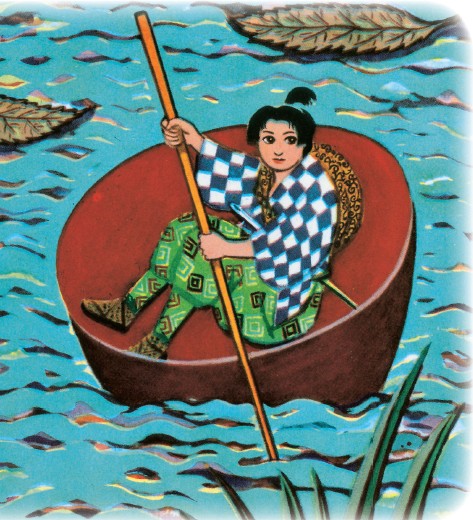

When he landed he was astonished at the crowds of people walking the streets. He feared he would be crushed to death in a short time, so he hid behind a big stone. He could hear the clomp-clomp of many clogs around him, and the clink-clink of swords when fierce looking warriors strode past, and the neighing of many horses. He saw wonderful wooden houses and temples and shrines. “Oh,” he thought, “this is a busy and wonderful city!” In spite of his danger, Issunbōshi was glad he had come. He was able to observe many things without anybody noticing him.

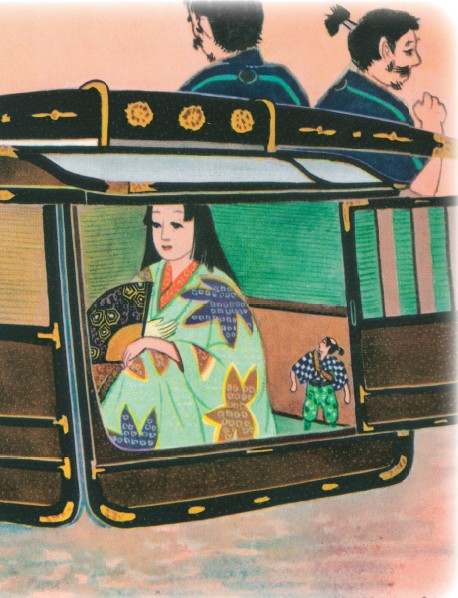

As he looked, he saw a beautiful lacquered palanquin pass by borne by sturdy men, and he heard a clear voice from inside commanding them to stop. As the men rested to mop their brows, Issunbōshi ran out and, from behind, climbed into the furthest corner of the palanquin.

Nobody noticed him—least of all the little princess seated inside, who was too busy fanning herself and pouting, for she was very tired and uncomfortable from the long ride. Being beautiful and spoilt and young, she did not think of her bearers, who were much more tired and hotter than she.

“You may start up again,” she called after a while, “and try not to jostle too much.”

Issunbōshi sat crouched in the dark corner as quietly as possible, and the princess sat still with a frown on her brow, for she wanted to be fanned by her maids and enjoy delicate sweet bean cakes.

Presently the palanquin was carried through a magnificent black wooden gate and the servants announced in a loud voice, “Hime-dono okaeri!” which means, “The Princess returns.”

Issunbōshi jumped off the carriage and hid himself behind a pillar, while the princess stepped down with much ado and was led inside.

When the bustle had subsided, Issunbōshi crept out once more, and called in a voice as loud as possible, “Gomen kudasai! Gomen kudasai! Pardon my intruding.”

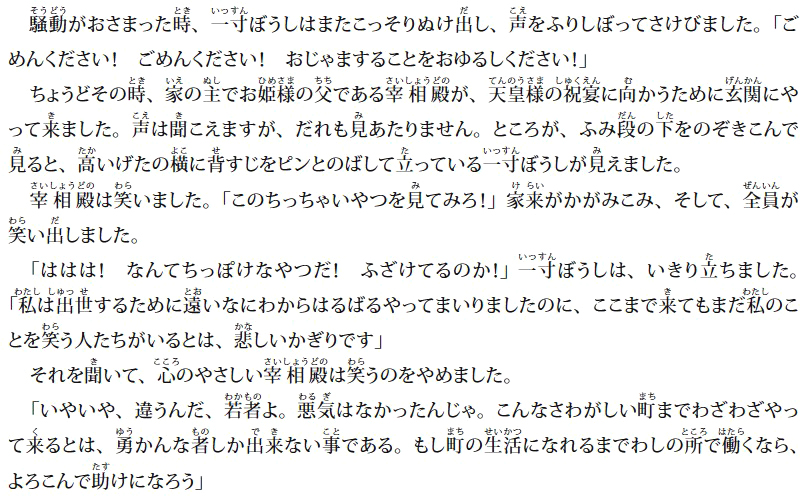

Just at that moment, the lord of the house and the father of the princess, Saishō-dono, came to the entrance on his way to a feast of the Emperor’s. He heard the voice but could not see anyone, until peering under the steps, he found Issunbōshi standing upright by the side of his high clogs.

Saishō-dono laughed. “Look at this wee fellow!” His retainers bent down, and all started laughing too.

“Ha ha ha! What a mite! How absurd!”

Issunbōshi drew himself up indignantly.

“I have come all the way from Naniwa to find a way to success, and it grieves me sorely to find that here too you make fun of me.”

Saishō-dono stopped laughing, for he was a kind man.

“No, no, my boy. None of us did mean it. I think you are most courageous to make your journey all the way to this busy city. I will gladly try and help you, if you are willing to work for me here and get used to city life.”

Issunbōshi, who had wanted nothing better all the while, promised he would try his best and from that day lived in the large mansion.

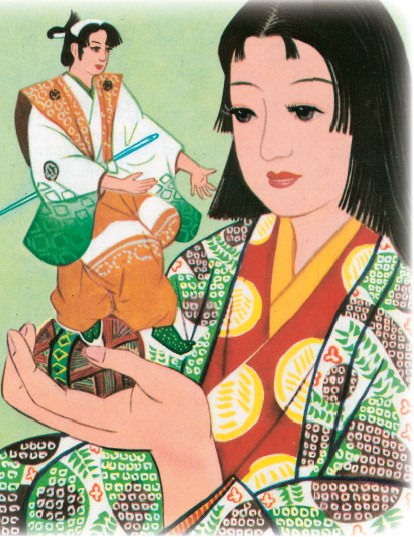

Now as soon as the princess saw him, she liked him ever so much and, being spoilt, wanted to have him all to herself. She liked to take him out on her rides and to have him near to play with at home.

“Issunbōshi, irrasshai! Come here!” she called all day long.

Issunbōshi liked the princess too, for with all her tantrums she was a lovable person, but he did so want to take part in the interesting work of the palace. He thought playing with the princess was no proper work for him.

One afternoon, after playing all morning, the little princess dropped off into a nap. Sitting close by, a tiny forlorn figure, Issunbōshi suddenly had a bright thought.

He had a small-sized box of Japanese sugar candies that Saishō-dono had given him. He ate them all; then he quietly scattered leftover bits around the princess and on her robes.

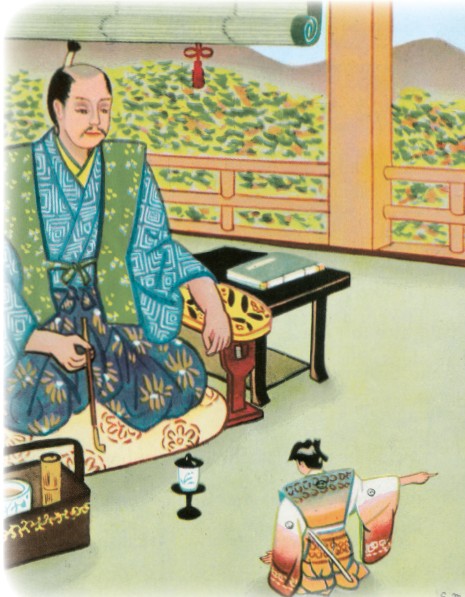

Issunbōshi went to Saishō-dono’s room, where the old gentleman sat on a thick cushion smoking a long handled pipe.

“Honored master,” he lamented, “the princess your daughter has robbed me of my precious palace cakes. I cannot stand it! Please remove me to other quarters.”

Saishō-dono, who was aware that his daughter was spoilt, picked Issunbōshi up in a hurry and went to the princess’ room. What he saw made him very angry and he shouted at the top of his voice, “What unlady-like appearance you make! You are no daughter of mine. Take her away from this palace! I do not want to see her anymore.”

And he nearly threw Issunbōshi down on the straw mat as he strode angrily away.

Issunbōshi was greatly astonished and very sorry for the commotion he had caused.

But in those days the word of a lord was a command. Issunbōshi had to follow the weeping princess away from the palace.

He thought he’d take her back to his home-in Naniwa until Saishō-dono’s anger had cooled off. So they found a fisherman’s old boat to take them down the Yodo River.

The princess went through all kinds of hardships she had never known before. She did not complain, but grew considerate and quiet and so gentle toward Issunbōshi that his heart ached for her.

There came a strong wind and, as the princess had no idea how to manage a boat, they drifted on the swift current until they were completely lost.

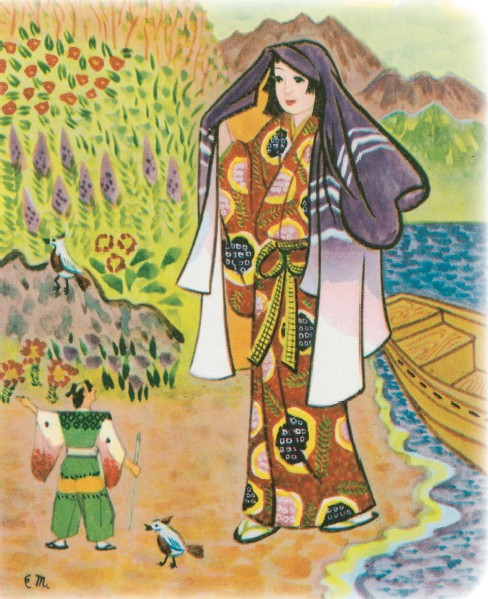

A few days later, hungry and tired, they landed on a mysterious island. Wonderful flowers grew all around. Birds of many colors sang on weird-shaped trees. They were very glad to be on land again and gazed around in wonder.

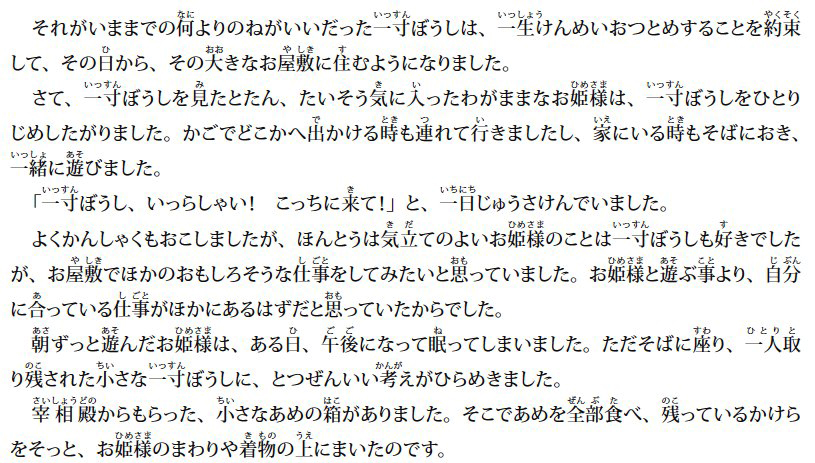

But suddenly there appeared a hideous-looking ogre, who rushed toward the princess, ready to take her and bear her away. With hunger and fatigue, the poor little princess fainted away. Then Issunbōshi drew his needle sword and shouted at the top of his voice, “Listen, you big lout! Who do you think this princess is? None other than the most honorable daughter of Saishō-dono of Sanjō. If you dare put your disagreeable hands on her, you can be sure of Issunbōshi’s great anger.”

The ogre thought, “Where on earth does that voice come from?” But when he looked down he saw a little pea-sized fellow standing with feet apart looking up at him.

The ogre burst into a roar of laughter.

“Great Heavens! A pea-sized fellow! What a bother. Better gobble him up!” And no sooner said than he picked him up and swallowed him down in a single gulp.

Now Issunbōshi felt himself slipping down a long slimy tunnel, which was the ogre’s throat, until he reached his stomach. It was dank and dark and awful, but Issunbōshi drew his needle, and running around pricked his stomach all over.

“Ouch! Ouch!” screamed the ogre. “What awful thing is happening!”

It hurt him so much that he rolled on the ground in pain and choked and choked. Issunbōshi was coughed up as high as his nose, so he stabbed him there many times, and still stabbing with fury, he reached the eyes and pricked him there too. By this time the ogre was sneezing and screaming and was fit to die with pain, so Issunbōshi jumped down to the ground. The ogre, thinking one of his eyes had dropped out, ran away at once, yelling at the top of his voice.

Issunbōshi knelt by the side of the princess and tried in his small way to revive her. After a bit, she became conscious, and feeling better, sat up and looked around. She then noticed that the ogre had left his magic mallet behind. In Japan, a magic mallet is the same as a magic wand, so the princess took hold of it at once and, waving it up and down, chanted, “Grow up, grow up, Issunbōshi. Grow up until you are an ordinary man.”

And wonder of wonders, each time she waved it Issunbōshi shot up, until he was a handsome, strong young man.

Both of them were so happy. Issunbōshi could hardly believe it. He smiled and stood up, and looked behind and in front of himself, and marvelled and marvelled.

How lucky the princess and Issunbōshi were to have the magic mallet to themselves. Some people spoil their luck by being greedy and wishing for too much. But Issunbōshi and the princess were wise and unselfish. They wished for just three more things.

First they wished for good food to eat. Then they wished for the ogre’s hoard, which turned out to be a fortune. Lastly, they wished for a big sturdy boat, on which they piled their treasures and went home to Kyōto.

The news that Issunbōshi, a grown man, had safely returned, bringing the princess and a fortune, spread rapidly until it reached the ears of the Emperor. He summoned Issunbōshi, and seeing what a promising youth he was, bestowed on him the title Horikawa no Shōshō.

Issunbōshi then invited his parents to Kyōto and treated them to all kinds of luxuries.

And naturally—in the way that all fairy tales end—he married Saishō-dono’s daughter and lived happily ever after.

I looked at my watch—as grownups do—and jumped up. The story had ended, just as time was up.