Kachi Kachi Yama (The Kachi Kachi Mountain)

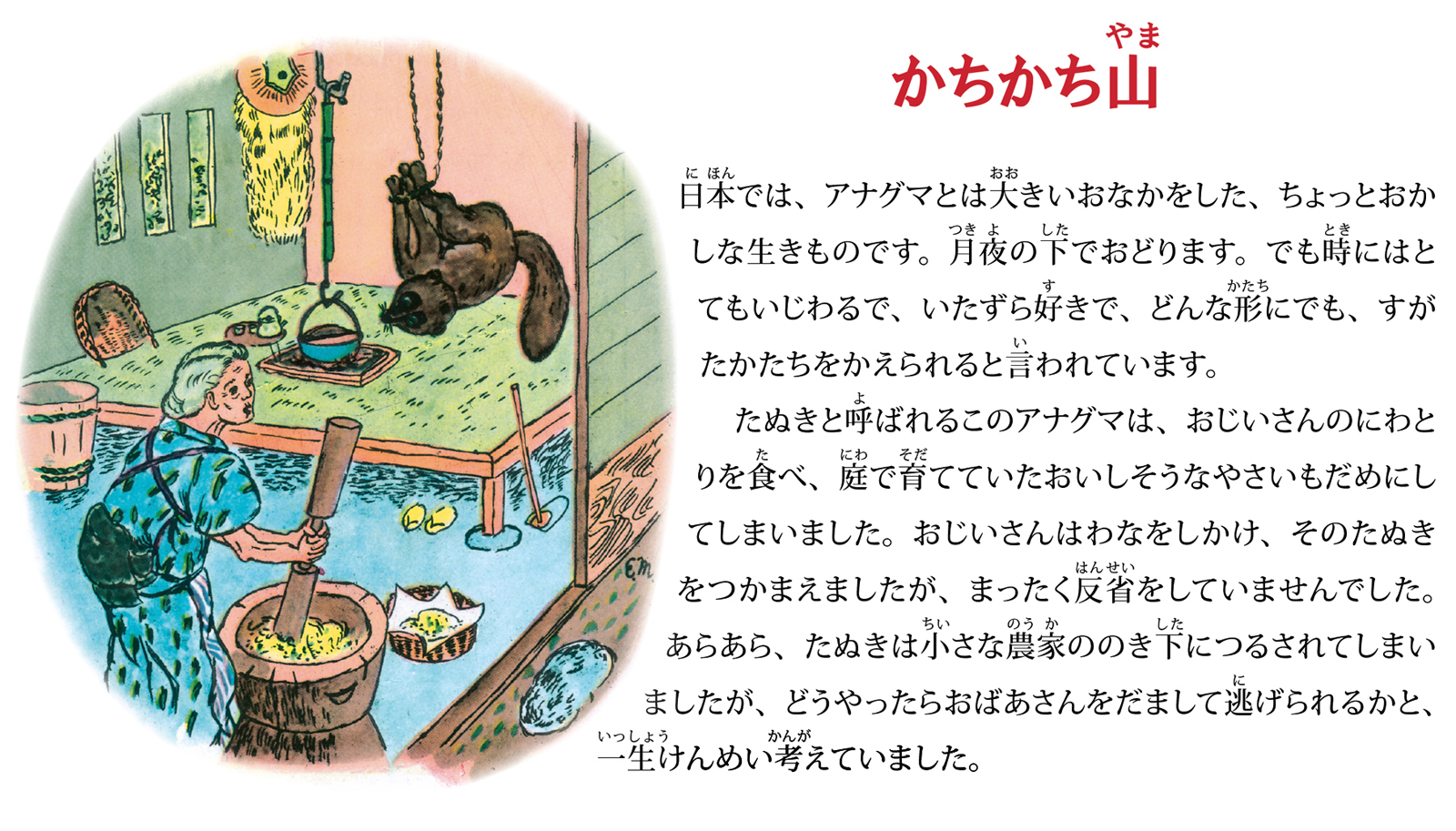

OVER HERE IN JAPAN, the badger is a funny little creature with a big tummy. He dances in the moonlight, but he can also be very mean and wicked and can change himself into all kinds of shapes.

Tanuki, the mean badger, ate Ojiisan’s chickens and destroyed the good vegetables in his garden. When Ojiisan set a trap and caught him, he was not sorry at all. Oh no, there he hung from the eaves of the little farm house, wracking his brains as to how he could deceive Obāsan and escape her.

Simple old Obāsan was very busy this morning. There was the wheat to be pounded, and the washing and the sewing and the cooking to look after.

First of all, Obāsan brought out her wooden mortar and started pounding the wheat. As she pounded she thought of the meal she’d cook for Ojiisan. It would be nice to be able to get hot badger soup for him, but how on earth with all this work on her hands! She looked up and caught Tanuki’s cunning little eyes staring at her.

“Dear Obāsan,” said Tanuki, “You are so busy this morning. I know you won’t be in time to finish everything before Ojiisan comes home. How about letting me help you for a while? You need not untie me. Just loosen the rope.”

“What a silly badger,” thought Obāsan. “He can’t even guess that he’s going to be cooked. Supposing I did let him work. It surely will save my creaking old bones.”

So Obāsan stepped up on the large stone by the engawa, the long veranda. She loosened the rope around the badger’s feet.

Scarcely had she done this when the cunning fellow sprang down on his four feet, and horror of horrors, snatching the pounder from the amazed Obāsan, hit her hard on the head and killed her!

Now, what else do you think?

Just killing Obāsan was not enough. He cut her up and made a soup out of her. Then he changed himself into Obāsan, except for his tail which stuck out behind.

Soon Ojiisan was home from the fields. “Okaeri nasai. Welcome back,” smiled badger Obāsan. “You really must eat your meal before it gets cold. I made it all by myself and had quite a busy time.”

Ojiisan sat down with a thump on his favorite cushion, eagerly rubbing his hands for he was feeling hungry.

“There is lots of badger soup,” said Obāsan. She sidled around the table being very careful not to show her tail. But Ojiisan caught sight of it. Quick as a flash he jumped up, but Tanuki was quicker.

He flew out the back way crying—“Bāsan shinda! Bāsan shinda! Your old woman’s dead.”

And suddenly Ojiisan knew everything.

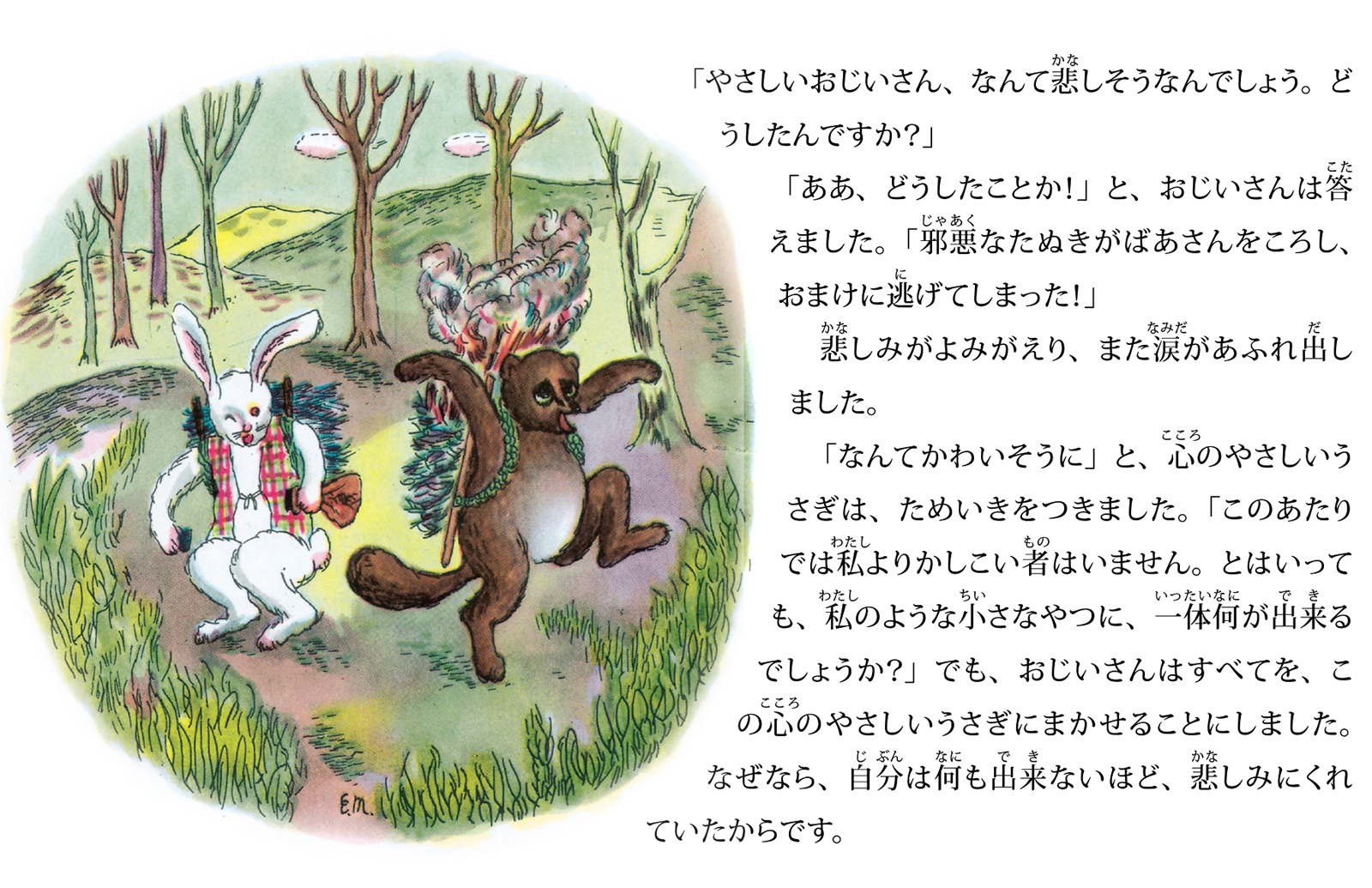

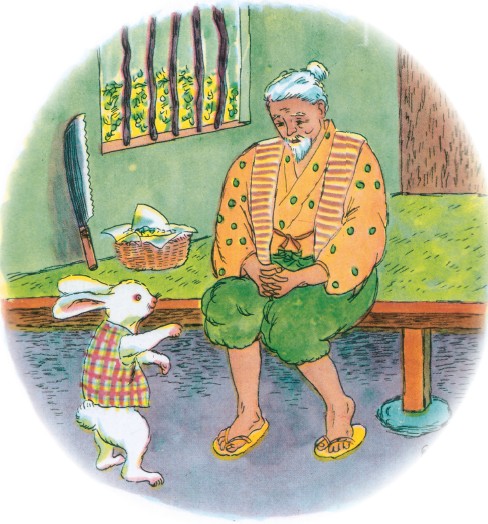

Oh, how the poor man moaned with helpless anger! The tears trickled down his cheeks. He wept so bitterly and sorrowfully that a little rabbit passing by heard him and peeped in.

“How you grieve, dear Ojiisan. What is the matter?”

“Alas,” was his answer, “the wicked badger has killed my wife and escaped me.”

And at the sad recollection the tears overflowed again.

“Poor people,” sighed the kind-hearted rabbit. “There is no one stronger than I around here. And what can I do, a weak creature like me?”

But Ojiisan said indeed he wanted to leave everything to Usagi, the gentle rabbit, for his heart was so full of grief he felt too weak to do anything.

Now the badger had hurried back to his evil smelling hole, and from it he did not stir for days. By that time he was quite hungry and was on the point of venturing out to Ojiisan’s vegetable garden again.

Just in time, the rabbit stole by with a scythe in his hand, and began cutting down sticks and making bundles of them. After that, he took out some nice-looking chestnuts and ate them with a great deal of relish and noise.

It sounded—bari, bari, bari, bari—and the badger who was very hungry, stuck his head out and saw harmless-looking Usagi chewing and enjoying himself.

“Usagi-san, my friend, what are you eating?”

“Chestnuts.”

“Won’t you give me some?”

“I will, if you carry half of this load of sticks over the hills yonder.”

Tanuki crept out and, taking the load of sticks on his back as country folk do, started walking in a hurry.

“Follow me, Usagi-san,” he cried in a guilty fashion. “I must be back in my hole as soon as possible.”

After a while Tanuki became fidgety and said, “Usagi-san, give me the chestnuts to eat now.”

“I will later. Carry the sticks over the hills first.”

So Tanuki, anxious for the chestnuts, hastened on.

“Usagi-san, give me the chestnuts to eat now.”

“I will later on. There’s still another hill in front.”

When they came to the top of the second hill, Usagi brought out his flints and struck them to start a fire.

Kachi, Kachi, Kachi!

“Usagi-san,” said the startled Tanuki, “what is that noise?”

“Oh, have no fear of that. This hill is called Kachi Kachi Yama.”

Next, the sticks on Tanuki’s back began to burn.

Bō—bō—bō!

“Usagi-san! What is that noise?”

“Oh, have no fear of that. The last hill we climbed is called Bō Bō Yama.”

“Is that so!” panted Tanuki. He was almost running, for all the while his back became hotter and hotter. He ran and ran, trying to get away for he was very frightened.

“Help! Help! I’m burning!”

What terror and pain he felt!

And the rabbit raised his voice too and cried, “Fire! Fire! Help! Help!” But no one came, for Usagi had taken care to bring Tanuki to a hill where nobody lived.

Tanuki rolled all over, yelling with pain and nearly suffocating with the smoke, and by the time the fire was out, his back hurt terribly.

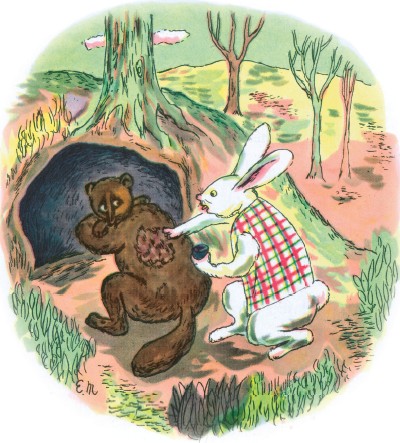

So he was unable to stir from his hole for another few days, when again Usagi hopped around to him.

“I did feel sorry for you the other day,” he said looking very innocent. “But I’ve brought you some good medicine.”

Tanuki who was still aching all over said, “What a good idea. I cannot reach my back. You rub it in for me.”

Now the medicine was none other than squashed beans mixed with red pepper, which is the worst thing for burns.

“Itai, itai! It hurts! It hurts!” moaned Tanuki, and the tears poured down his ugly face.

“The more it hurts the better for you,” cried Usagi, meaning it. “You’ll be weak for days but it can’t be helped.” And away he went, laughing inside.

Well, the next week Usagi thought he’d see Tanuki again.

“What is it this time?” grunted Tanuki, for he had scarcely recovered and felt weak. He thought that Usagi was a silly, harmless creature and that his awful medicine had certainly done him no good.

Usagi wriggled his pink nose and sniffled the air.

“It’s lovely outside today. Look at the green grass. It stretches a long way on, as far as the other side of the bank where the sea is. It would feel delicious to float on the water today.”

“That sounds interesting and we might be able to catch fish to eat.”

The thought was so good that, weak as he was, Tanuki clambered out of his hole and together they found their way to the beach.

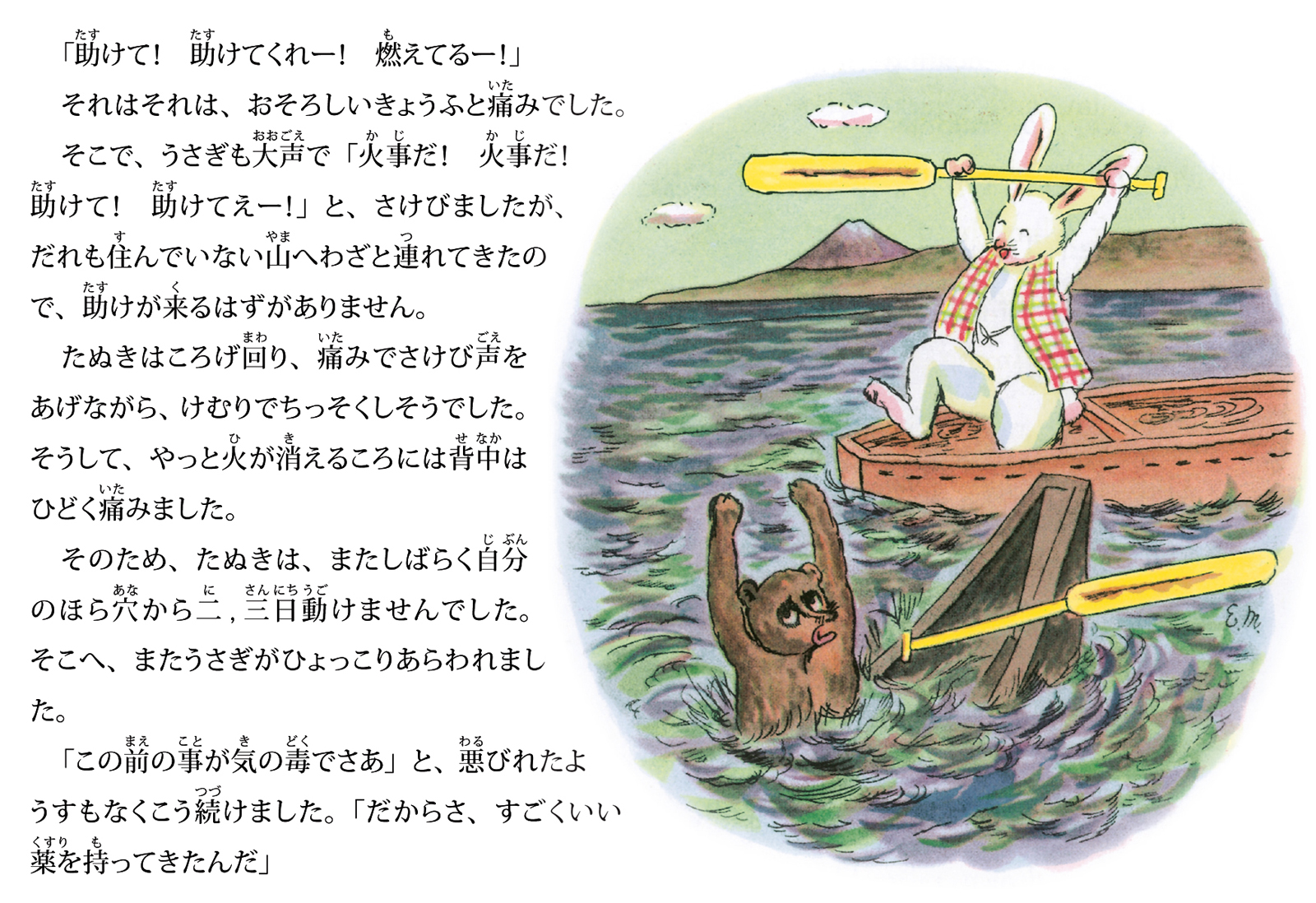

Now Usagi had made two boats, one of wood and the other of earth. The earthen boat was well polished and shiny. This was the one Usagi offered Tanuki, while he took the roughly hewn wooden one.

“I say, Tanuki,” cried Usagi, “We’ll race to the open sea and fish there.”

So off they started, and the faster Usagi went in his light wooden boat, the harder Tanuki rowed his, trying to overtake him.

But of course, there is no such thing as an earthen boat floating for long. Very soon it began to crumble.

“Oh! Oh! Oh! My boat is breaking up!” screamed Tanuki.

But Usagi stood up in his boat and cried aloud:

“Down you go to the bottom of the sea, for you have caused harm to many. You killed Obāsan and deceived Ojiisan! Besides all that you are still plotting evil!”

Then, terror-stricken, Tanuki jumped up and down and was beside himself with fear and anger, but the boat sank rapidly and he was left to drown miserably.

Usagi rowed back to Ojiisan’s house and told him, and Ojiisan, who still sat rigid and weary, stretched his hand out and stroked Usagi’s soft white head and ears.

“Thank Heavens!” he sighed. “The meek can be strong too. I will now live peacefully.”

This is how Tanuki was punished for his wickedness, and thenceforward Usagi lived with Ojiisan to keep him company in his loneliness. For all I know, they got on very well together.