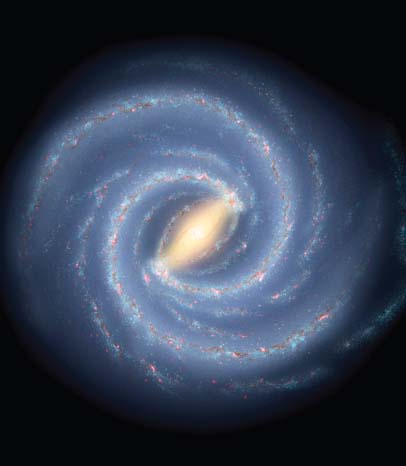

Fig. 9.3. Top and side views of a spiral galaxy, our Milky Way. Stars orbit a miniature ellipticalgalaxy-like central bulge with a supermassive black hole at its center. We do not see the dark matter that is also present. The galaxy is like a thin disk, approximately one million billion miles thick, and fifty times as wide. (Image from NASA/JPLCaltech.)

Fig. 9.4. Example of an elliptical galaxy, the gargantuan NGC 1132, the bright region at the center of the photo. Stars trace out elliptical orbits in all manner of orientations about the center of the galaxy. (Image from NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage [STSel/AURA]-ESA/Hubble Collaboration; acknowledgment: M. West [ESO, Chile].)

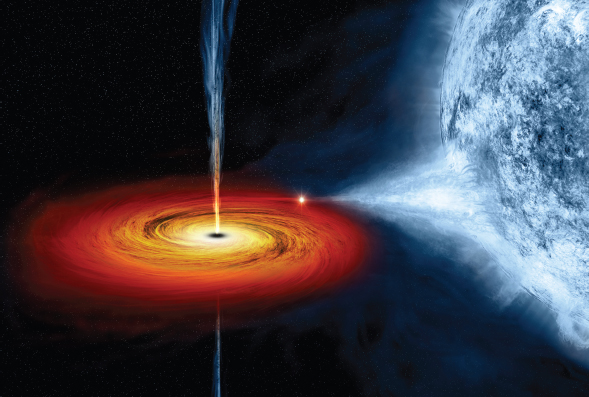

Fig. 9.5. Illustration of a stellar black hole (at the left) attracting atoms from a blueish-appearing star (at the right). As material falls into the hole, vertical-directed beams of light are released. (Image of x-ray from NASA/CXC/M. Weiss; image of optical from Digitized Sky Survey.)

Fig. 9.7(a). A two-dimensional map representation of Earth. (Image from NASA/WMAP Science Team.)

Fig. 9.7(b). A very precise two-dimensional, outward-looking all-sky map representation of the temperatures of the variation in cosmic microwave background radiation from space. This is a snapshot of the oldest light in our universe, from 380,000 years after the big bang. The yellow represents higher temperature; the red, the highest temperature variation of +0.0002 degrees Kelvin; and the dark blue, the lowest temperature variation of –0.0002 degrees Kelvin, compared to an average of about 2.7255 degrees Kelvin (above absolute zero). (Image from NASA/WMAP Science Team.)

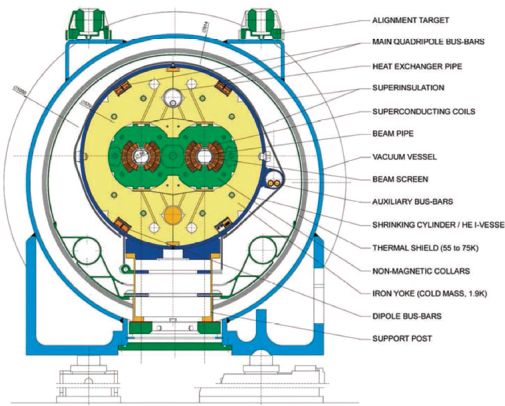

Fig. 9.8. Cross section of the Large Hadron Collider's (LHC's) beam tube and dipole-magnet assembly. The “eyes,” shown white at the center, are the beam tubes, and the nearly surrounding collection of sectors contains the superconducting magnet windings, shown in brown. The remaining structure provides mechanical support, cooling, and thermal isolation so that the windings can operate at just 1.9 degrees Kelvin (above absolute zero). (Image from Wikipedia Creative Commons; file: The 2-in-1 Structure of the LHC dipole magnets.jpg; authors E. M. Henley and S. D. Ellis. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.)

Fig. 9.9. View of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) beam tube and magnet assemblies of the collider ring inside the ring tunnel. (Image from Wikipedia Creative Commons; file: CERN LHC Tunnel1.jpg; author: Julian Herzog; website: http://julianherzog.com. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.)

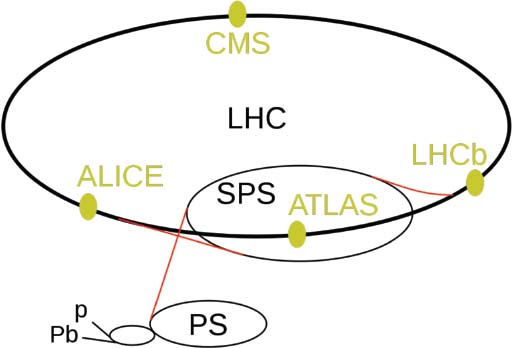

Fig. 9.10. Angled-view sketch of the circular rings of the Proton Synchrotron (PS) and Super Proton Synchrotron pre-accelerators to the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), with its experiment test stations shown in green. The path of the protons (and ions) begins at linear accelerators (marked p and Pb, respectively). They continue into the booster (the small, unmarked circle), then to the PS and the SPS. Red lines indicate how particles are fed in opposite directions into the two beam tubes of the LHS. (Image from Wikipedia Creative Commons; file: LHC .svg; drawn by Arpad Horvath with Inkscape. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5.)

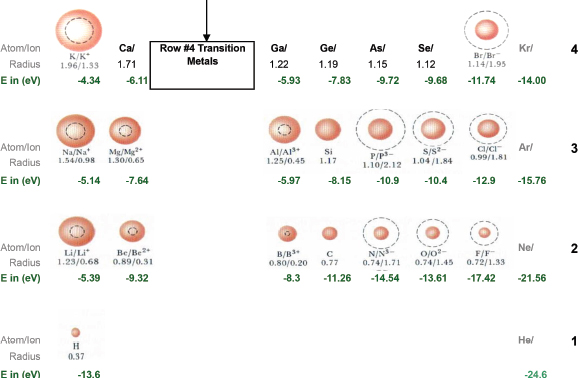

Table D.1. Outer Electron Energies* and Relative Sizes of Atoms and Filled Valence Subshell Ions of Some of the Elements. (*The negative of measured ionization energiers.) Note that atoms and ions are unrealistically shown as solid spheres and dashed circles. (In part from Fine and Beall, reference E, Table 16.3, p. 554, with permission from Dr. Leonard W. Fine.)

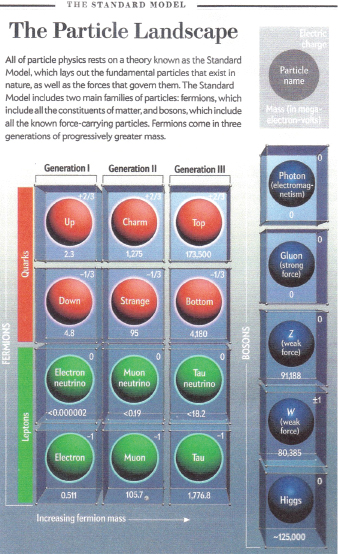

Fig. 9.11. The fundamental particles of the Standard Model.