Six

BEACHES AND CLIFFS

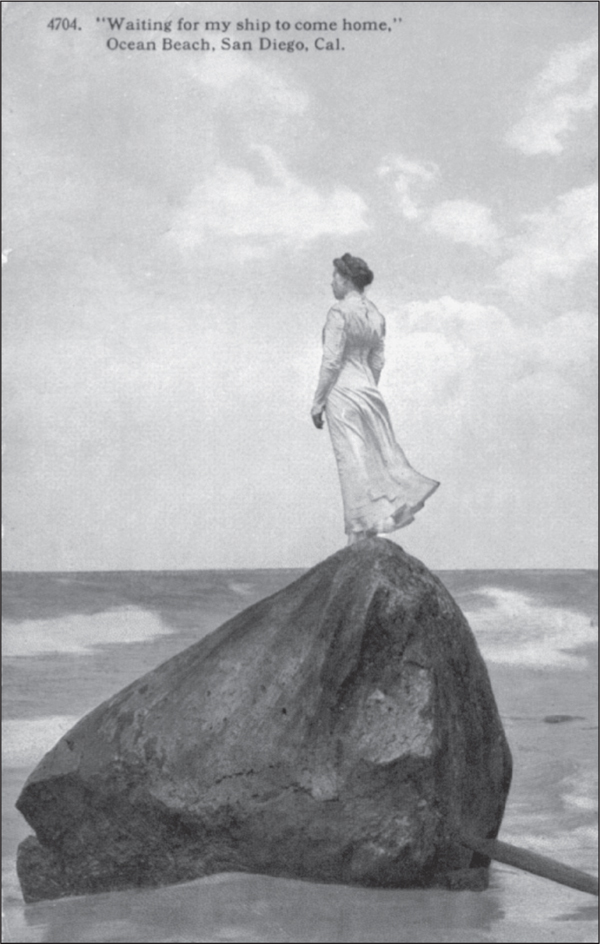

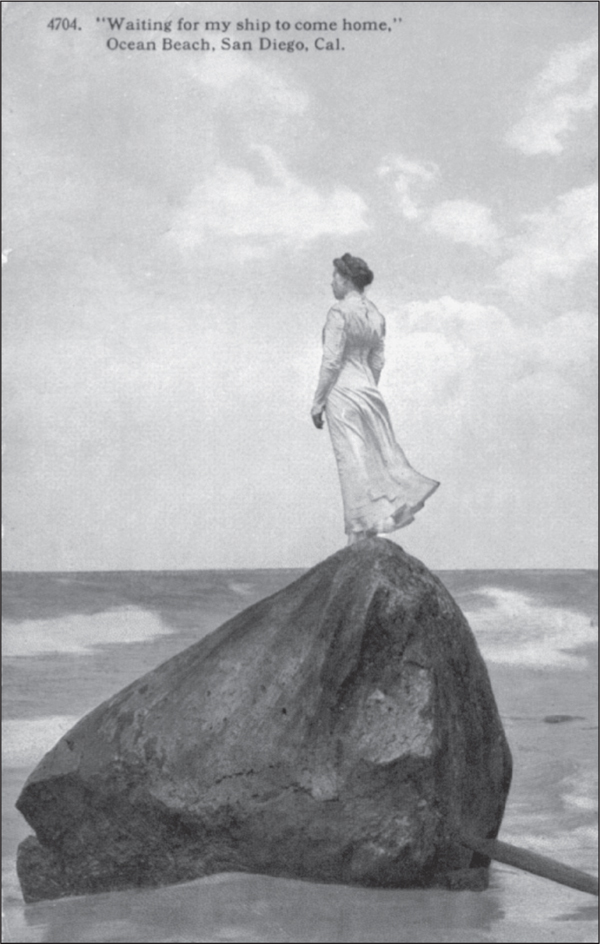

In this romanticized 1913 postcard, a lovely lady stands on a rock and gazes out to sea as the waves lap the shores of Ocean Beach. According to the postcard caption, she was waiting for her “ship to come home,” although there would have been no place for it to berth in Ocean Beach.

There was no market for sunscreen when these early beach scenes were taken. Whether bathers or spectators, people came to the beach fully dressed.

The man in this family photograph sports a black wool suit with a little skirt, typical for the early 1920s, while the woman wears a head-to-toe swim garment that would not be complete without ballet slippers for her feet. The little boy appears to be the best “suited” for swimming and may even get wet.

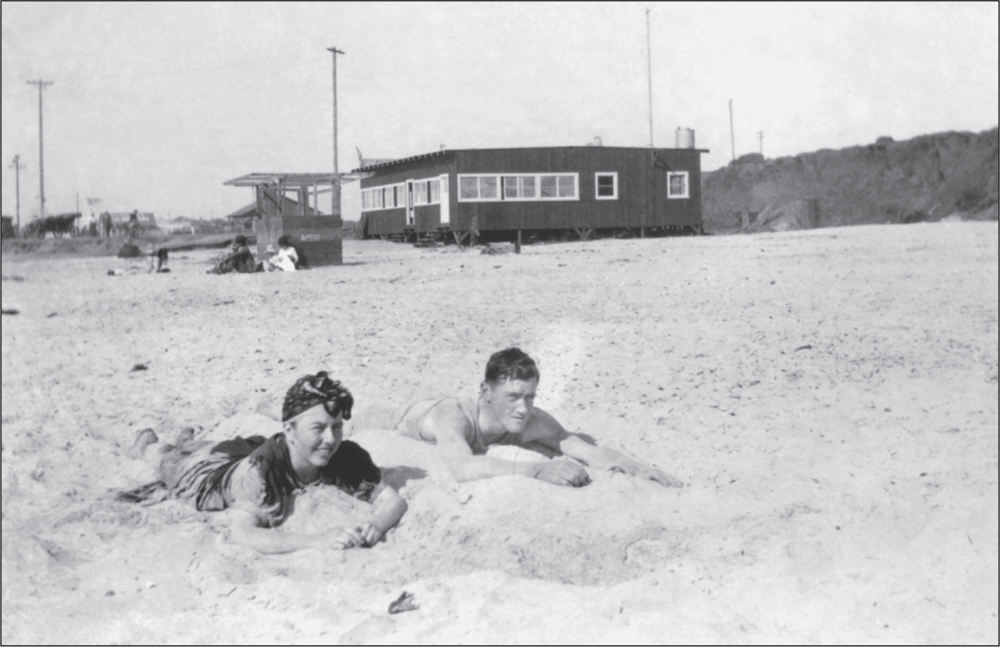

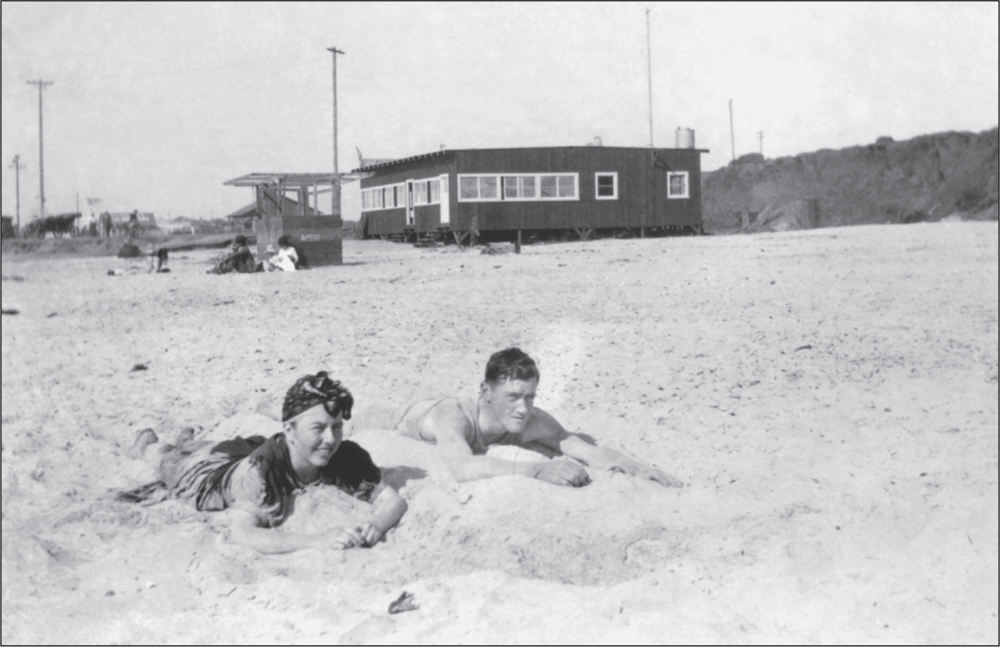

The warm sand was inviting after a cool dip in the Pacific. These beach lovers are relaxing at the end of Newport Avenue.

Kelp piled up on the sand (as seen above) has long been a common sight at the beach after a high tide, and the kelp beds off Ocean Beach are some of the largest in the world, ensuring a constant supply of the messy seaweed. In 1939, a storm caused so much kelp to pile up around the Ocean Beach police substation that city trucks had to be called in to haul it away. Kelp does have its good points, though. Southern California’s offshore kelp beds provide a rich habitat for a variety of sea creatures, and alginate derived from kelp—which has been harvested off the coast of San Diego since 1911—is used in dozens of food products, including ice cream. The boys below knew what to do with kelp: play with it! In this 1916 photograph, brothers Alfred and Ralph Cobb amuse themselves in front of the Benbough bathhouse at the foot of Newport Avenue.

This group of bathers thought Christmas 1922 was a great day to take a dip at Ocean Beach. The photograph was made into a postcard, undoubtedly so these folks could brag to friends in colder climes about Ocean Beach’s near-perfect weather.

New Year’s Day presented another opportunity to romp in the surf as these 1923 photographs attest. Were these the same hardy souls who posed a week earlier? The average ocean temperature in January is 59 degrees—brrrr!

Ocean Beach was also a great spot for a picnic. This 1930s photograph shows the Jack Reick family gathered for an outdoor meal at the foot of Newport Avenue. It may have been a Sunday as they are dressed in their finest, although one family member (center) has apparently lost her hat.

By the 1930s, umbrellas were a common sight on the beach. On the left, a lifeguard dory can be seen parked on the sand. Lifeguards had to paddle these difficult-to-maneuver wooden boats through the surf to rescue swimmers in need of help.

A popular swim area among locals was the False Bay (now Mission Bay) swimming hole. Before Mission Bay was dredged in the late 1940s, northern Ocean Beach was on the bay’s southern shore. The area was later developed into Robb Athletic Field.

As a young teen, Ned Titlow could not get enough of the beach and swimming. Except for his first four years and another three years in the military, Ned spent his entire life near the Pacific Ocean in his beloved Ocean Beach. The longtime OBcean, who died in 2011 at age 87, was a founding member of the Ocean Beach Historical Society.

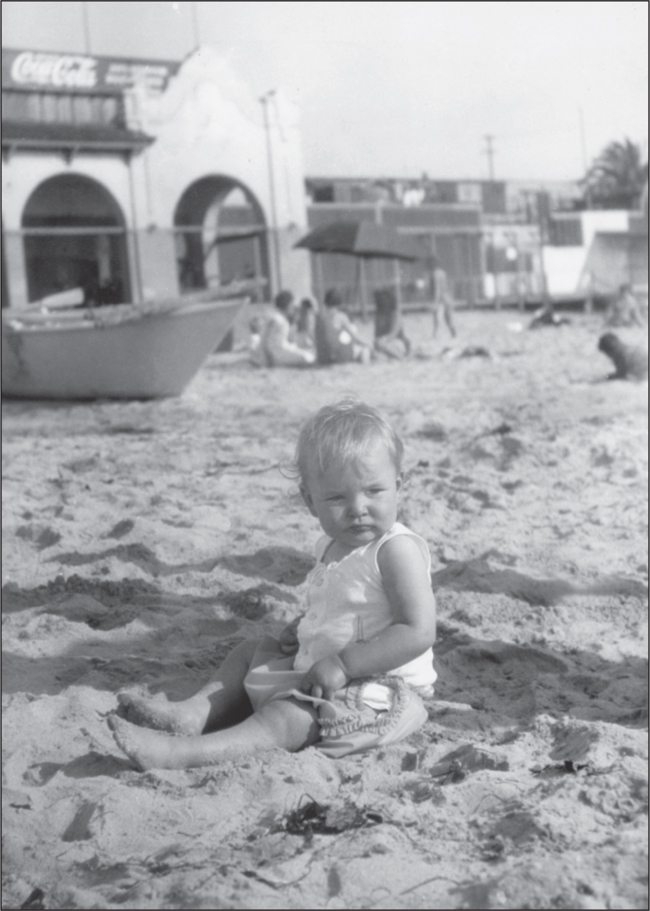

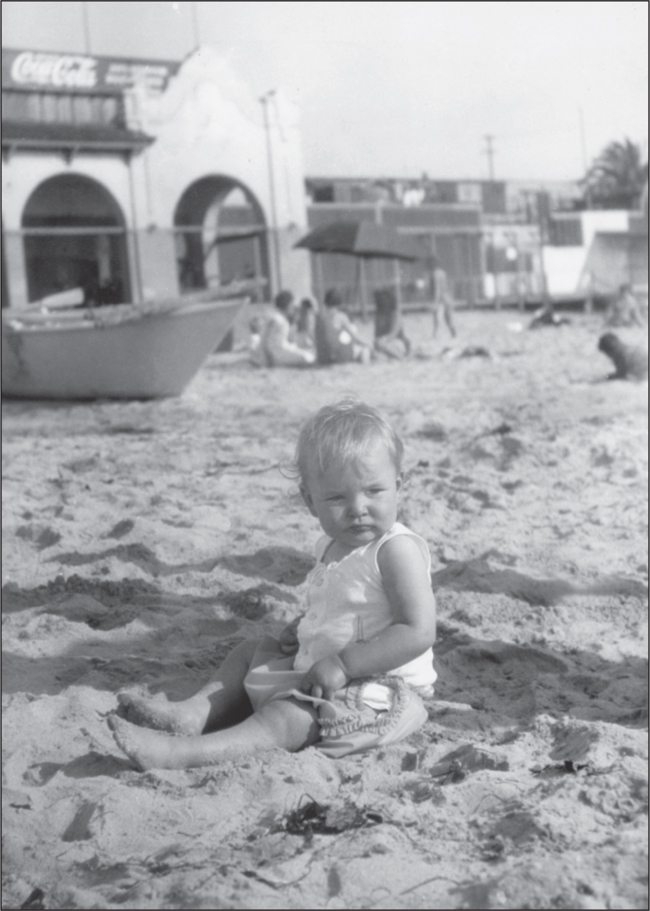

Jane Meiners, a native of Ocean Beach and one year old at the time this photograph was taken, was pretty much raised at the beach. She was very good at staking out her own territory, and nobody dared mess with her sand bucket.

The huge lump at the bottom of this boy’s feet is a stingray. Frank McElwee Jr. seems to be in awe of this sea creature, possibly from hearing stories about the painful, but not deadly, sting it can deliver with its long barbed tail. Stingrays are common along the Pacific coast and especially like the warm waters of Southern California.

This heavy-duty swing set was reached via stairs that led down from the west end of Niagara Avenue. Apparently, there were no age restrictions.

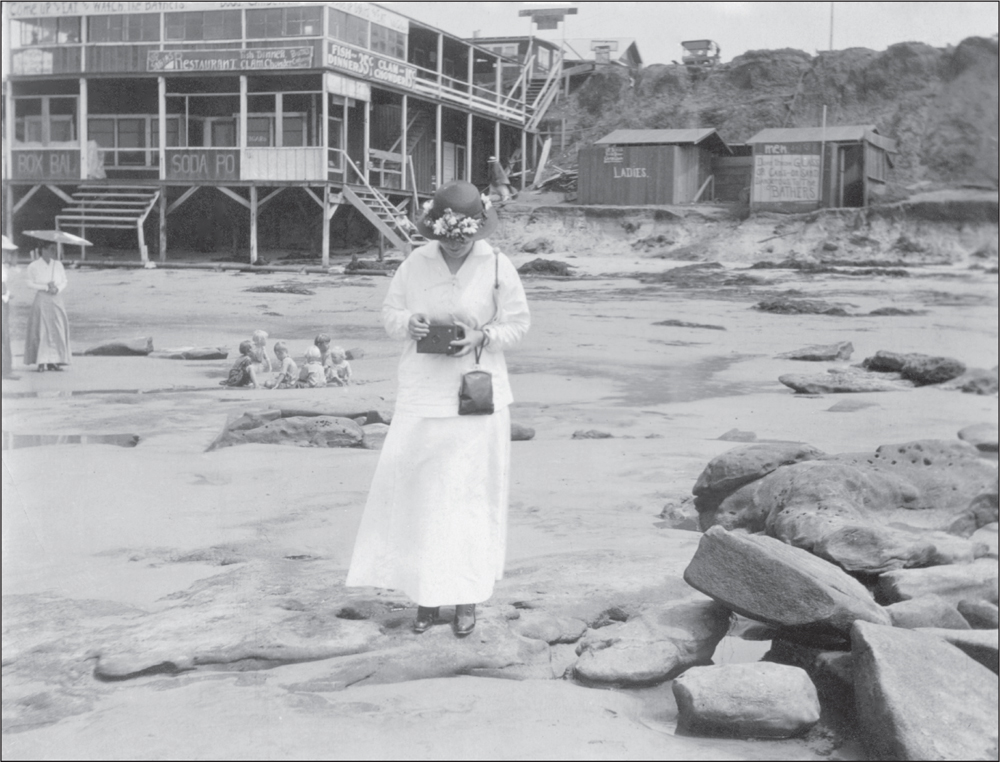

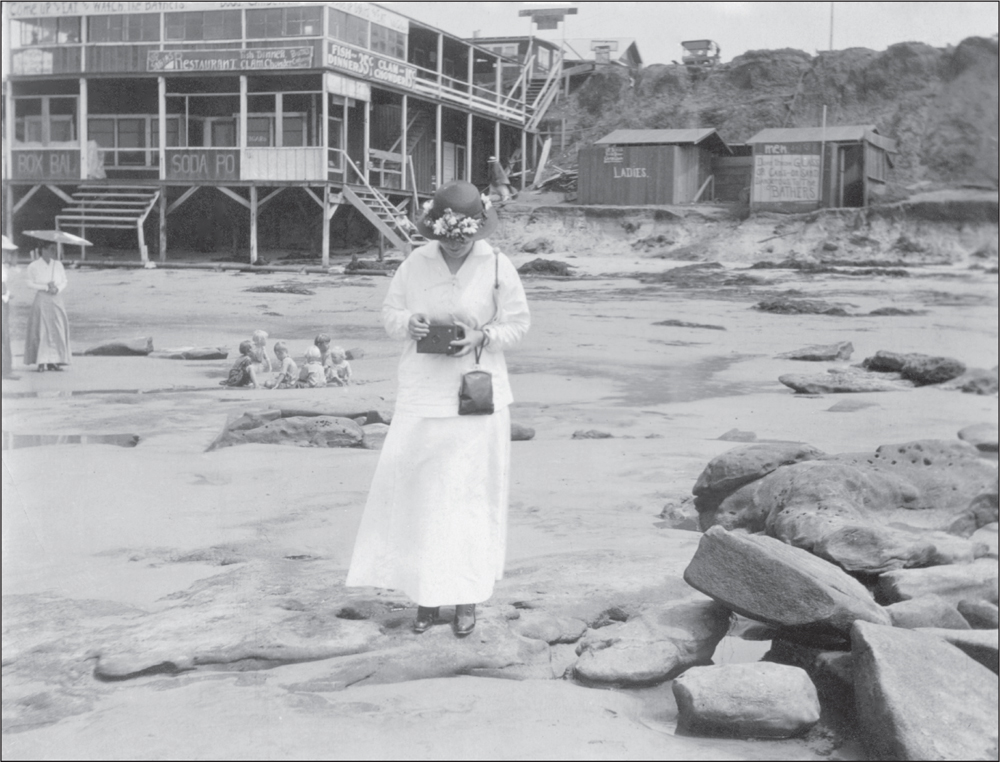

Hmmm . . . where is that shutter button? This photograph taken of a woman taking a photograph was snapped near the old fish house at the foot of Niagara Avenue. Note the fancy changing rooms for “Ladies” and “Men” at upper right.

A boy stands in a boat near the south end of Ocean Beach. The iconic Silver Spray Plunge, which opened in 1919, can be seen in the background.

Fishing off the cliffs of Ocean Beach was a popular pastime. Using a long bamboo pole and a heavy weight, fishermen could overhead cast beyond the surf line. Then, they could hand the pole to their sweetie to reel in the catch.

A fisherman tries his luck off the cliffs below Collier’s Shack, the home built by D.C. Collier at the foot of Coronado Avenue (then Pacific Avenue) in 1887.

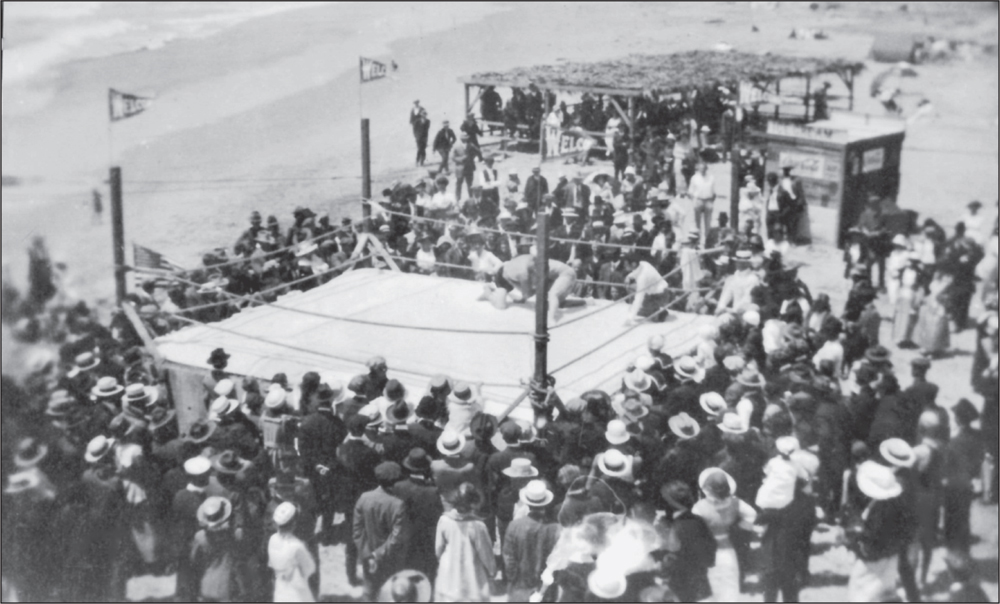

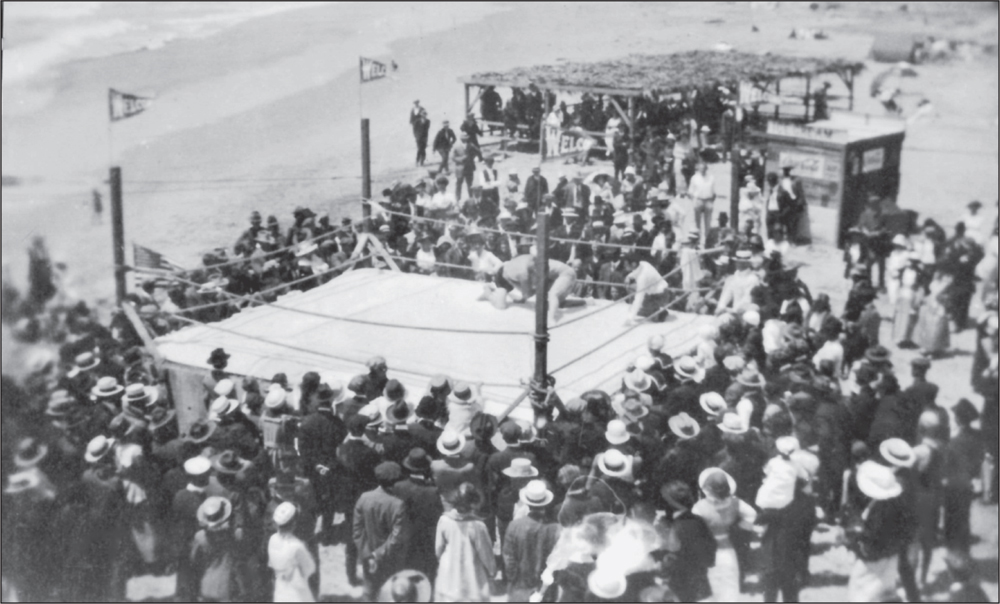

To draw tourists and to entertain locals, Ocean Beach often sponsored special events, such as boxing and wrestling matches on the beach. On July 4, 1918, the Camp Kearny wrestling championship was decided in a makeshift beachside ring, such as shown here.

Contestants in a 1920s bathing beauty contest pose on the rocks south of the Silver Spray Plunge. But wait, is that really a member of the “fairer sex” seated at far right? The “beauty” with hand on hip and smirk on face was prankster Jay Turley.

When the strongmen on the beach needed a gal to join them in gymnastics, Maddy Dibble was their go-to girl in the mid-1940s. Although slight in build, Maddy was a weightlifter who could overhead press 100 pounds!

Frank McElwee and Grace Peace, shown here in the sand at the foot of Newport Avenue, met and married in Ocean Beach. Their wedding was held at the Newport Avenue home of Grace’s mother, Mary Peace, who owned several prime pieces of Ocean Beach property, including the Niagara bluffs lots on which Camp Holiday, an early auto camp, was built.

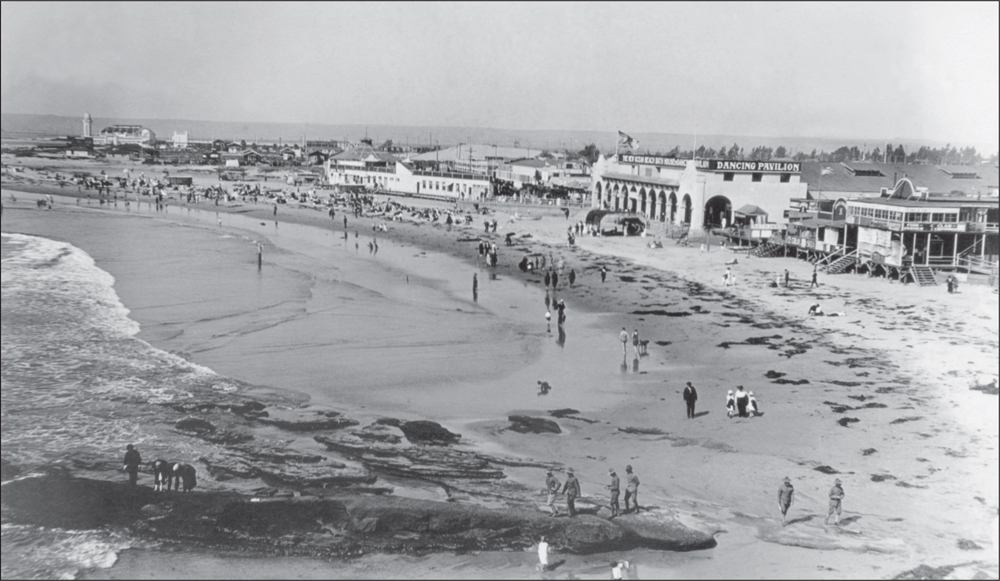

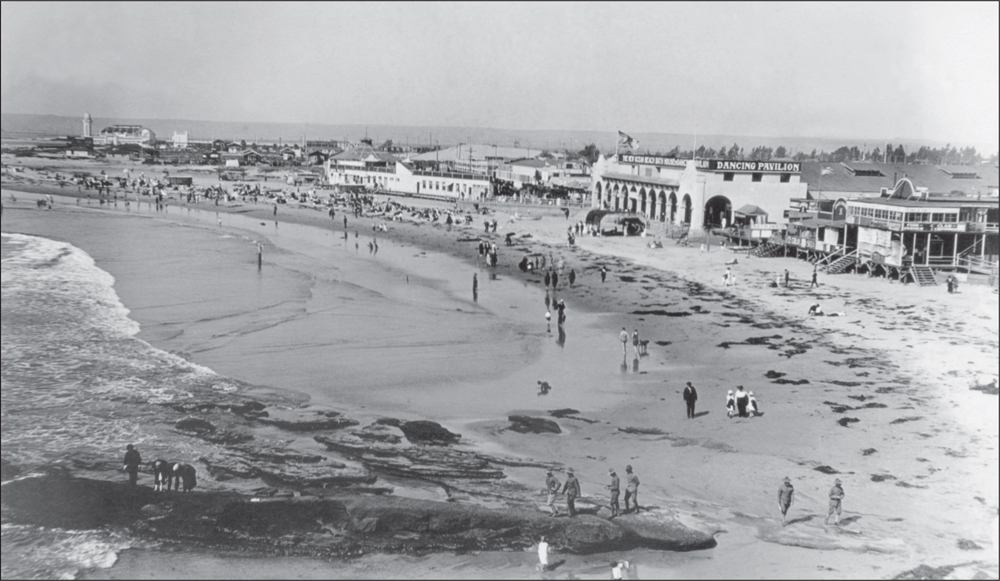

This 1917 panoramic photograph shows a large crowd enjoying themselves at Ocean Beach. Note the World War I soldiers exploring the tide pools in the foreground. With its many attractions, Ocean Beach was a popular destination for servicemen during this era.

Surfing has long been popular in Ocean Beach, from the northern edge of the community (by Dog Beach) to Sunset Cliffs Natural Park, about three miles south. These surfer hunks from the 1940s, seen here with their wooden plank boards, were regulars in the water off Sunset Cliffs. From left to right are Kimball Daun, Rob Nelson, Bill Sayles, Joe Todye, Lloyde Baker, and Bill “Hadji” Hein.

The Sunset Cliffs surfers, by now all seniors, recreated their original photograph 50 years later. Four of the boards seen here are ones used in the earlier shot. These men exemplify the expression, “Old surfers never die, they just paddle away.”

In 1924, this three-generation group of modern California woman, including the Pollock girls, enjoyed exploring the Ocean Beach area in their 1922 Dodge touring car.

In the 1910s, Crawfish Cove, located at the end of Santa Cruz Avenue, was a popular place for getting one’s feet wet and for checking out the tide pools. Houses today perch precariously near the edge of the sandstone cliffs overlooking this scenic spot.

Recognizing the beauty of Ocean Beach’s cliffs and rock formations, the City of San Diego erected an observation pavilion high above the water at the foot of Del Monte Avenue, with a stairway leading down to the sandstone ledges.

This rock formation, called “Needle’s Eye,” once stood off Sunset Cliffs. By the 1960s, it had all but disappeared due to erosion.

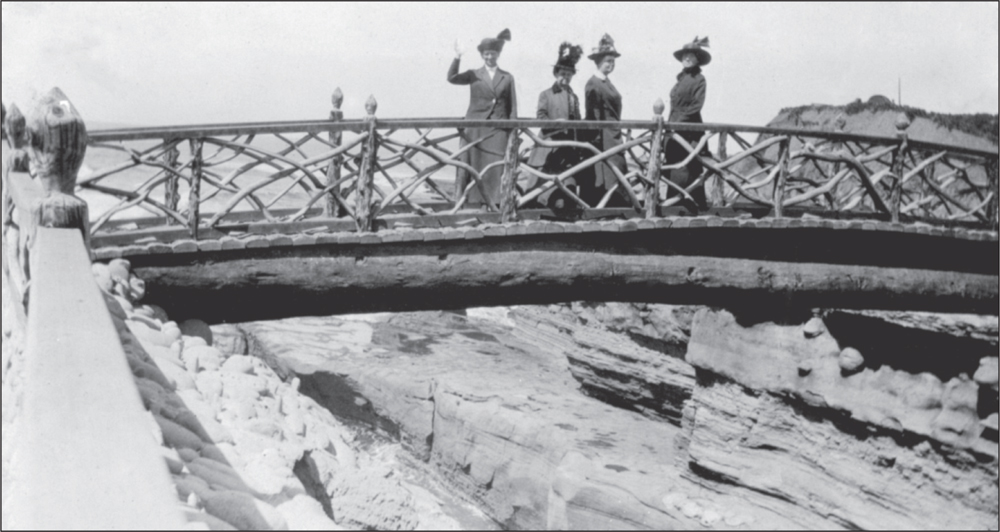

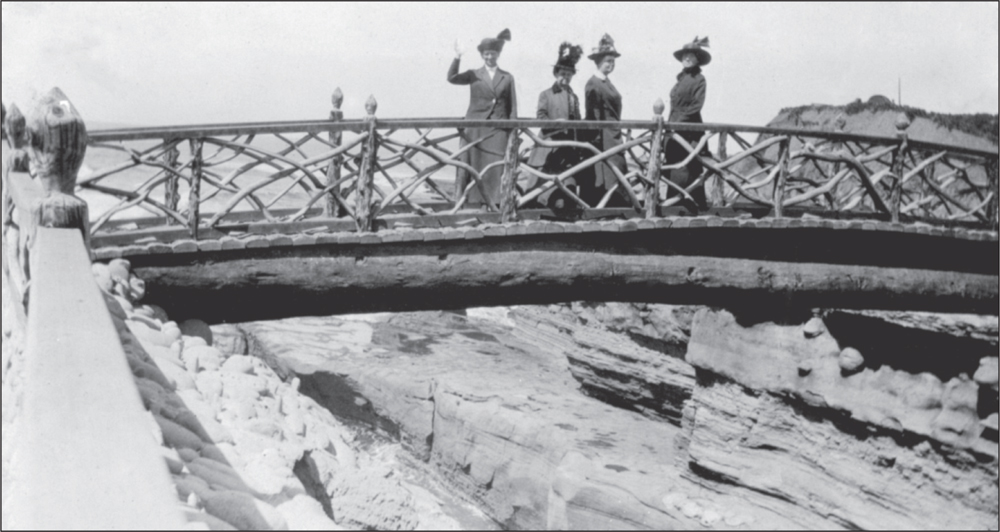

In 1915, sporting goods magnate Albert G. Spalding built a beautiful park along Sunset Cliffs. At the time, he owned all the land between Point Loma Avenue and Hill Street, from Catalina Boulevard to the ocean. These women are crossing a bridge that once stood at Froude Street and Sunset Cliffs Boulevard.

The park had a decidedly Asian theme. Its rustic bridges were designed and built by a Japanese architect hired by Spalding. Other nice touches included cobblestone walls, walkways lined with lavender ice plant, concrete steps leading down the side of the cliffs, and fancy lighting. The $2 million park was a must-see for out-of-towners coming to San Diego for the Panama-California Exposition in 1915–1916. Spalding was still making improvements to the park when he died on September 9, 1915.

In 1924, John P. Mills bought 300 acres of Sunset Cliffs from A.G. Spalding’s widow and refurbished the park. The beautifully landscaped area shown above was directly across the street from the mansion Mills built for himself. By 1926, Mills was spending all of his time developing his Sunset Cliffs subdivision. He gave the park to the City of San Diego, but during the Depression, it fell into disrepair, and the fanciful bridges and shaded gazebos eventually disintegrated or rotted away. Today, a few chunks of concrete and some broken staircases at the bottom of the cliffs are all that remain of what was once an Ocean Beach showplace.

This early photograph shows picnickers exploring the tide pools of Sunset Cliffs at low tide. Although the southern cliffs stretch far beyond Ocean Beach’s official street border at Point Loma Avenue, they were considered part of Ocean Beach proper during the early part of the century. Most pre–World War I postcards identify Sunset Cliffs as being in Ocean Beach.

In 1929, a person slipped into a crevice at Sunset Cliffs and had to be rescued by a policeman. Similar mishaps have happened many times since. Cliff visitors are often unaware that rocks that are regularly drenched by salt water are often covered with slippery black algae, called “black ice” by locals, and can cause dangerous slips. Today, posted signs at the cliffs warn visitors of unstable cliffs and other hazards.

This iconic rock near the end of Froude Street, shown at very low tide in the early 1900s, looks much the same today. Local surfers call this resting place for pelicans, cormorants, and seagulls “Bird Shit Rock” to distinguish it from La Jolla’s famed “Bird Rock.” Officially known as Ross Rock, it is the southernmost piece in the California Coastal National Monument. This 1,100-milelong monument is made up of more than 20,000 pieces—small islands, rocks, exposed reefs, and pinnacles.

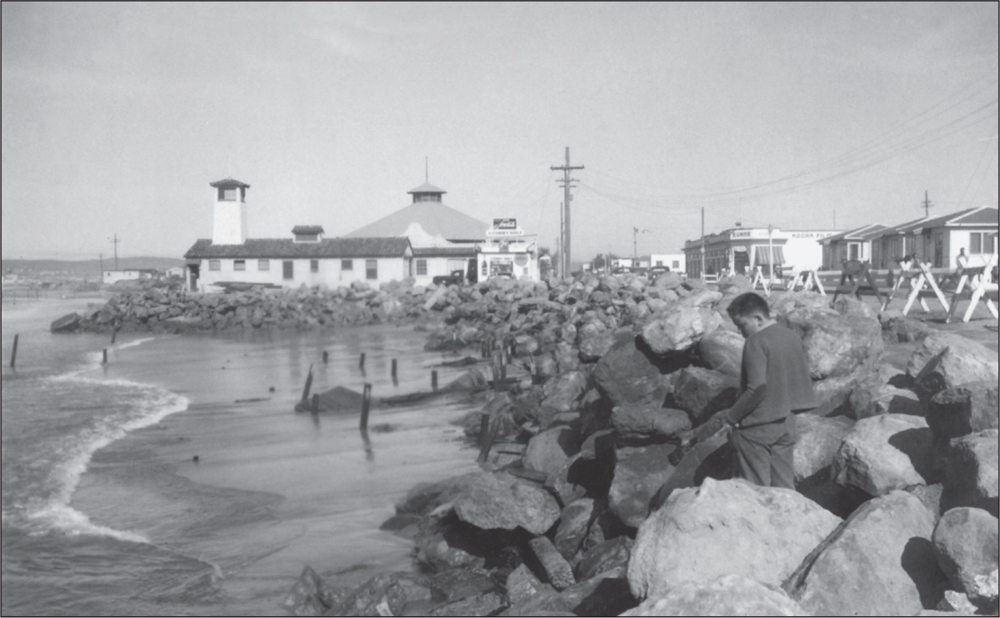

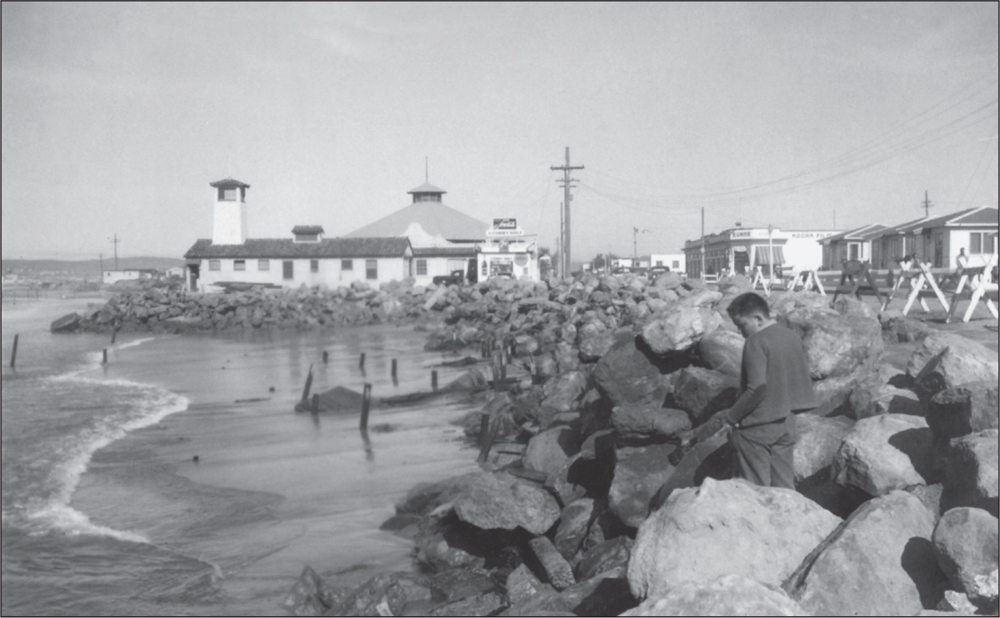

The Ocean Beach lifeguard station on the beach at the foot of Santa Monica Avenue was badly damaged by a severe storm in 1939. Huge waves tore away part of the foundation, but the building was able to be repaired, and a rock barrier was erected to protect it from future storms.

The wooden boardwalk in Ocean Beach (left) was ripped apart by the same 1939 storm that damaged the lifeguard station. Although San Diego receives only 7 to 10 inches of rain annually, torrential rains can occur and often result in low-lying beach areas being flooded. Amazingly, the “bungalettes” at Ocean Village Hotel (right) survived the devastating 1939 storm. This was probably due to the fact that they had been built on sturdy pilings that were anchored to bedrock.

This Sunset Cliffs viewing area and attached staircase also were victims of the 1939 storm. The upper bluffs are uncompacted sandstone and vulnerable to rain and wind erosion, as well as undercutting by wave action.

In the mid-1940s, looking south down Abbott Street toward where the flatiron building had been, huge boulders used as riprap were mostly what one saw. Today, beach replenishment programs have reclaimed much of this area, and most of the unsightly boulders have been removed.

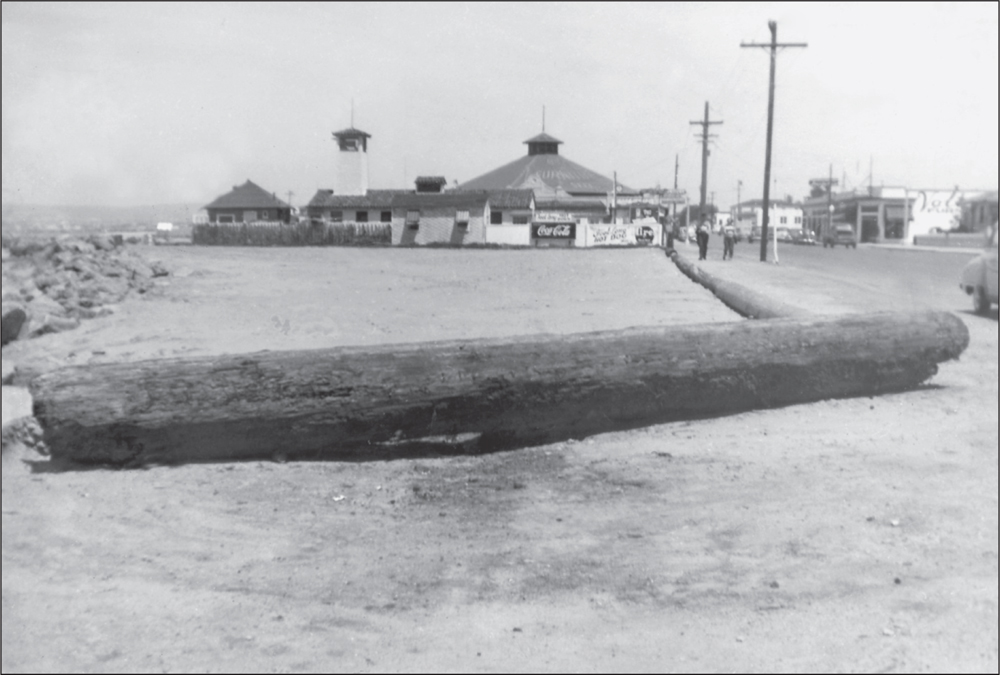

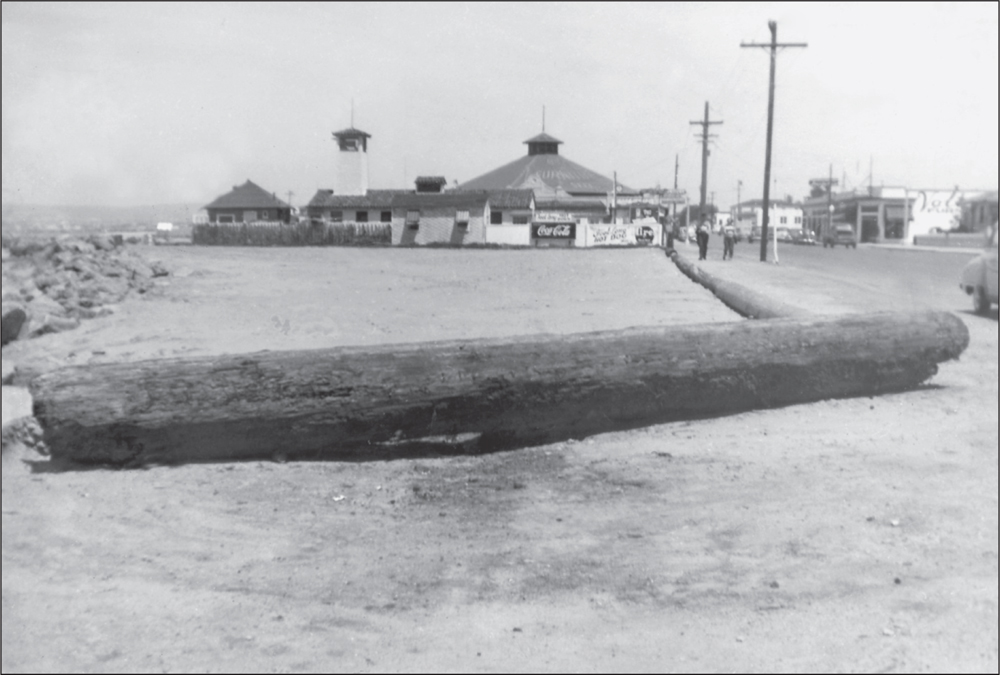

The logs in the foreground outline where the flatiron building, demolished in 1941, once stood.

This view of the beach shows the rock barrier that was erected after the destructive 1939 storm to protect the lifeguard station and other buildings along Abbott Street from high surf.

Between major storms in 1939 and 1940, Ocean Beach got a white Christmas when an avalanche of foam came sweeping in on the tide. On Christmas Day 1940, foam several feet high rolled onto Ocean Beach’s shores, much to the surprise and delight of the locals. It turned Ocean Beach into what looked like a winter wonderland, with drifts up to 10 feet high. At the time, it was said to be a natural occurrence, but not much explanation was given. Locals saw it as a great photo op.

On Christmas Day 1940, these two young women took their holiday picture in the sea foam.

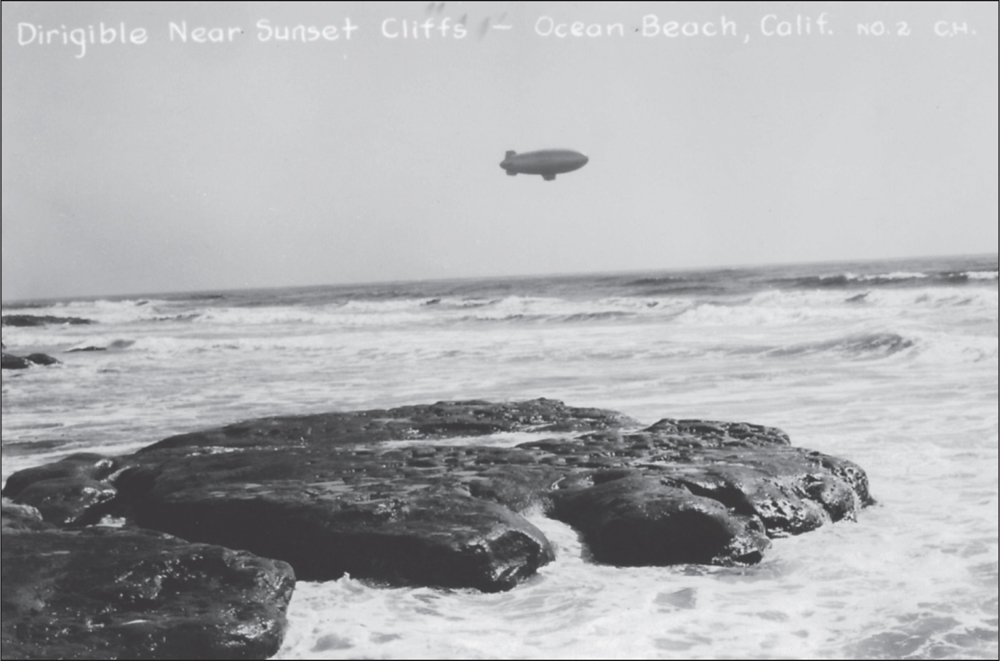

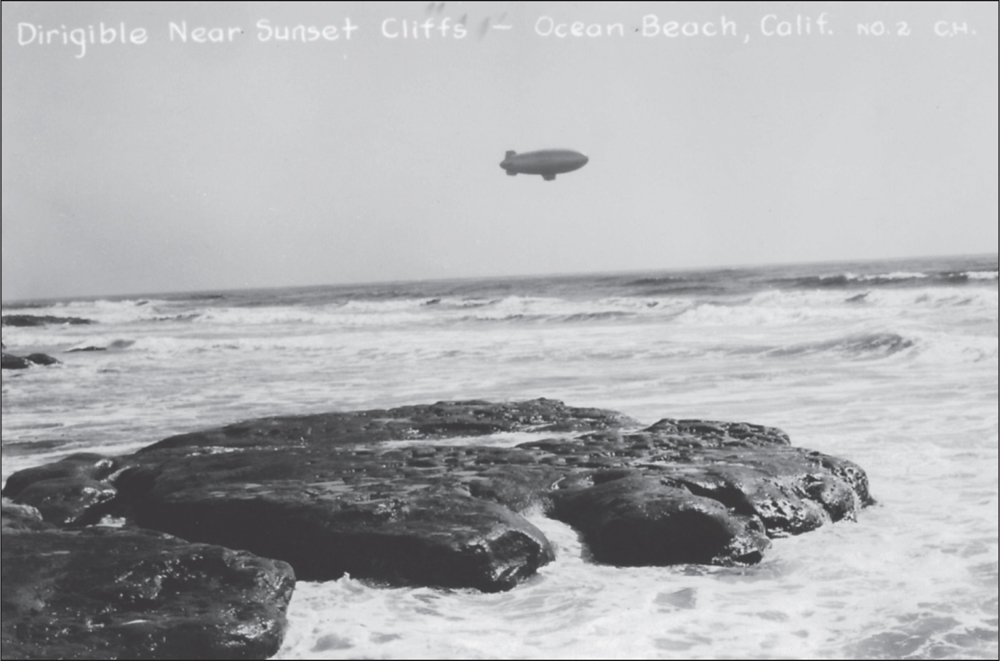

Apparently, Ocean Beach was not only a great place to live, but also a great place to fly over. In the c. 1915 postcard above, a biplane dips precariously close to a group of people gathered on a rock formation called “The Turtle.” Below, a World War II–era dirigible gets a good view of the Sunset Cliffs area as it passes over Ocean Beach.