Seven

DID YOU KNOW?

Ocean Beach’s Municipal Pier, dedicated on July 2, 1966, is the longest concrete municipal fishing pier on the West Coast. Visitors can come and spend the day on the 1,971-foot-long structure equipped with bathrooms, a restaurant, and even a bait shop for those who want to try their luck with a fishing pole. The pier was built to replace the 1915 fishing bridge that once linked Ocean Beach to Mission Beach and was torn down in 1951.

The same year the pier opened, Ocean Beach hosted the 1966 World Surfing Championships, and many spectators found the pier the perfect spot for viewing the competition. Winner of the women’s division was Ocean Beach surfer Joyce Hoffman, who subsequently was featured on several magazine covers, including Sports Illustrated. Among the male competitors, local surfer Skip Frye was a favorite with the crowd, but he lost out to Australian Nat Young.

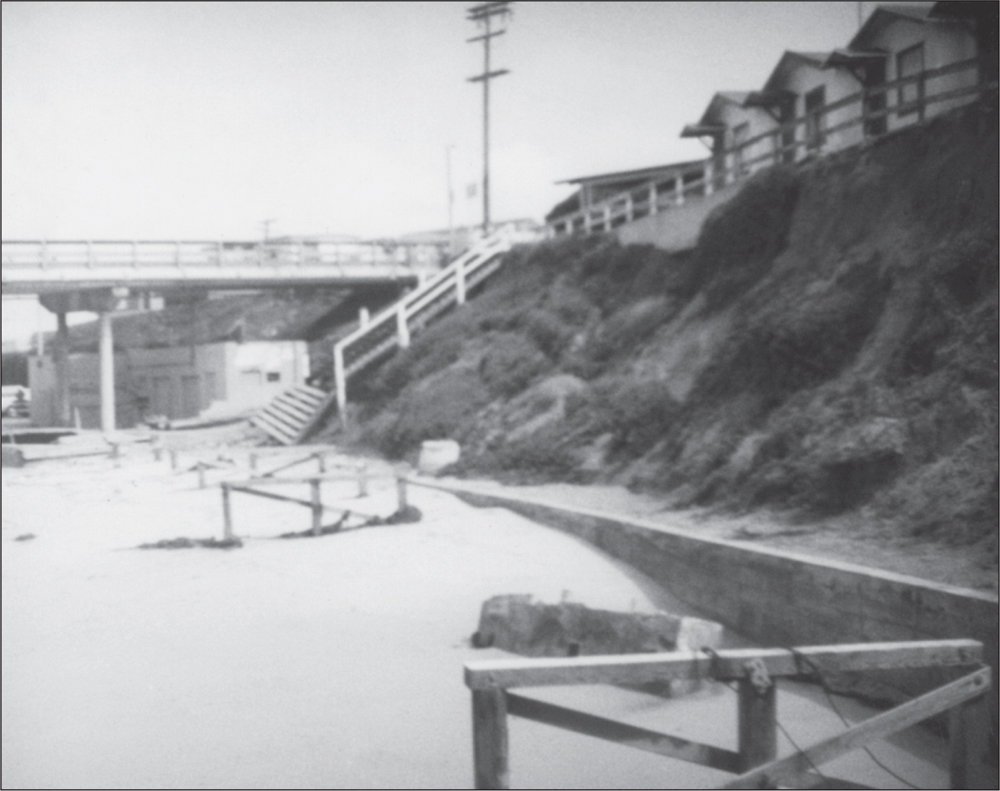

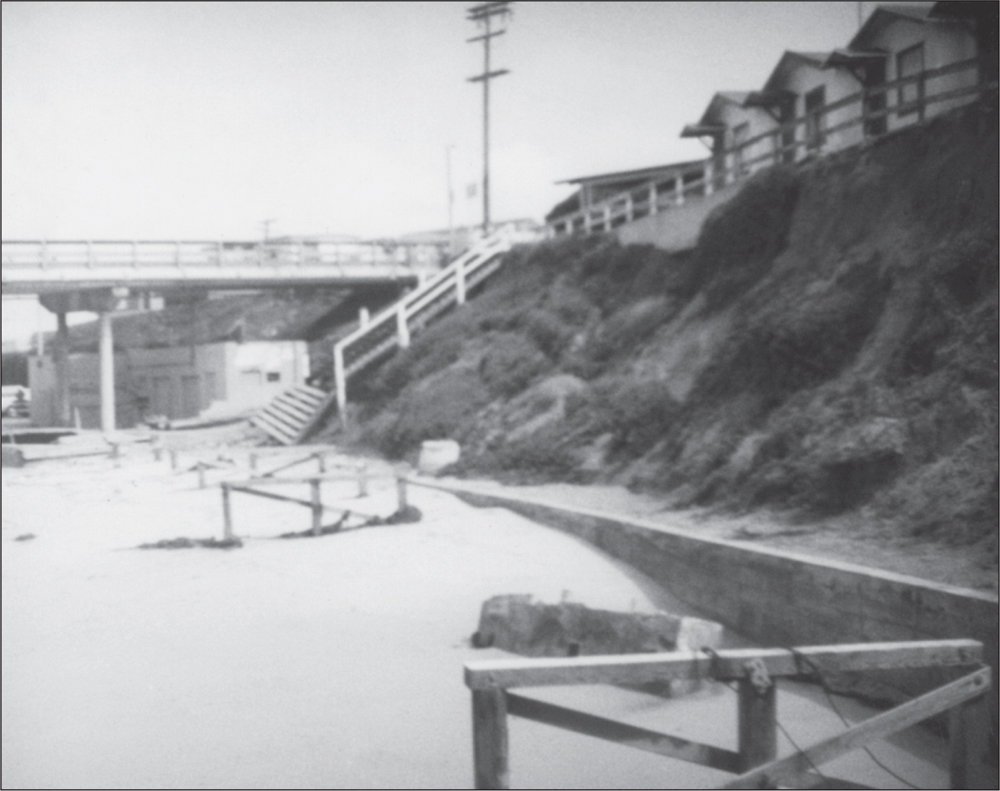

In the 1980s, Ocean Beach’s old wood plank boardwalk, which had been damaged by a storm, was replaced by a new concrete boardwalk and seawall. The walkway, which runs from the Silver Spray Apartments north to the end of the pier parking lot, is a heavily used thoroughfare along the beach. The houses at top right are the original Camp Holiday bungalows, built in 1923. The pre-pier photograph below shows a stretch of the earlier boardwalk with its white rail fencing.

Ocean Beach cottages like these have been preserved thanks to the efforts of Priscilla McCoy, longtime Ocean Beach Historical Society board member. In the late 1990s, Priscilla led a movement to identify cottages in Ocean Beach that had been built between 1887 and 1931 and still retained their original exteriors. She then persuaded owners to participate in what became known as the Ocean Beach Cottage Emerging Historical District. She and Sally West prepared the necessary paperwork to present to the San Diego Historical Resources Board and subsequently, in October 2000, gained the board’s approval for the district, which contains 72 individual homes exemplifying Ocean Beach’s historical development.

This wave motor once operated below the cliffs at Santa Cruz Avenue. The device was invented by Alexander Jones, who believed the ocean could be harnessed to supply energy for Ocean Beach. The car above was attached by cable to a generator, and the power of incoming waves moved it up and down an incline to produce electrical power, but not very much. The project was soon abandoned, and the innovative machinery quickly became a photo prop, used here by three members of the Turley family.

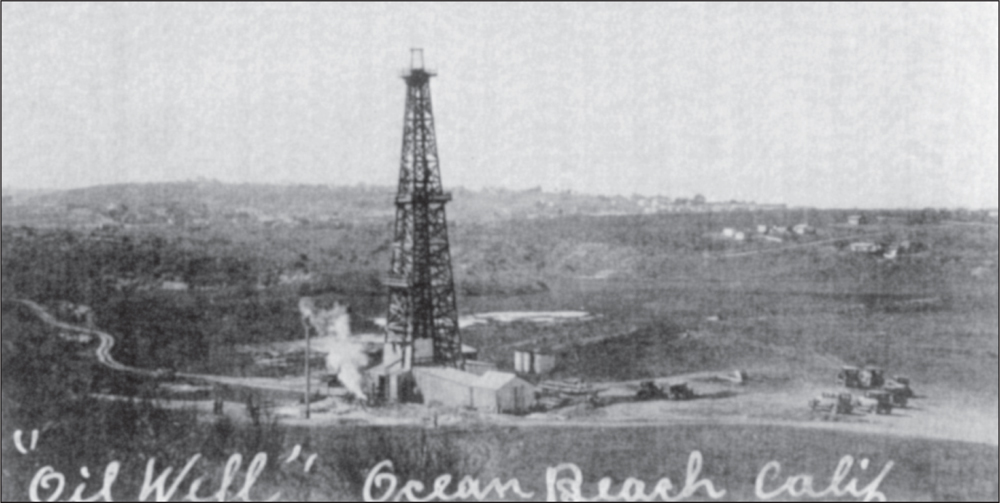

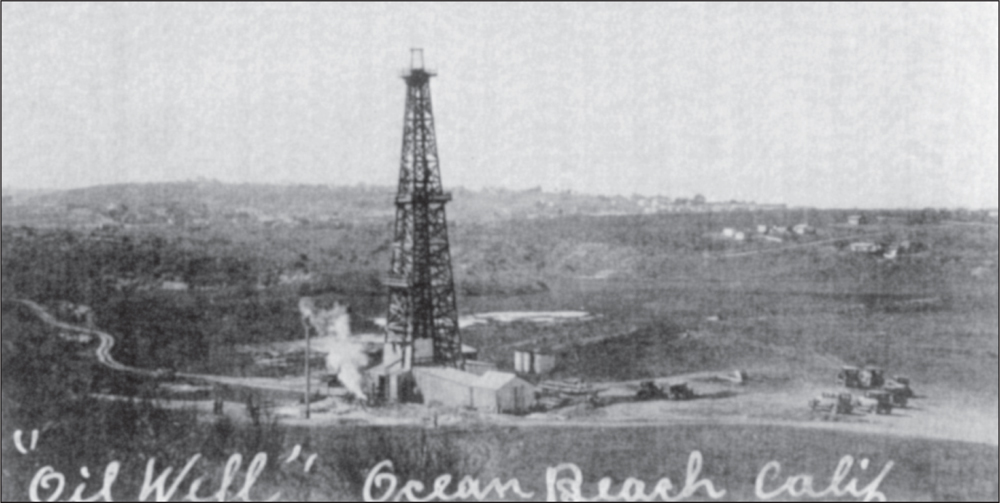

Could there be oil in Ocean Beach? There were no gushers here, but at least three attempts were made to locate “black gold” in the beach area, the earliest taking place when Billy Carlson financed an effort to drill for oil on Pescadero Avenue in 1895. Carlson gave up after 1,200 feet. Then, in the 1920s, John P. Mills attempted to find oil on Sunset Cliffs, but with no luck there either. The final unsuccessful attempt came in 1929, when Borderland Oil Company drilled to a depth of 4,200 feet in Loma Palisades but got nothing. It was kind of like pouring money down a hole.

The oldest children’s kite festival in the United States got its start in 1948 in Ocean Beach as a 20th anniversary project of the Ocean Beach Kiwanis Club. The one-day festival, still held each year in March, is a free event in which children learn how to make and fly kites. It has expanded in recent years to include a street fair with food, crafts, music, and carnival rides. (Courtesy of Steve Rowell.)

Some of the world’s largest Torrey Pines can be found on Saratoga Avenue in Ocean Beach. Torrey pines are only native to two places: San Diego and Santa Rosa Island, off the coast of Santa Barbara. In the 1930s, a local WPA beautification project was to plant Torrey Pines along the roadway leading up to Cabrillo National Monument. Pine nuts were gathered from Torrey Pines State Park and grown into seedlings at the Saratoga Avenue nursery of San Diego County employee David Robert Cobb. Irregular watering and hungry critters doomed the highway project, but the trees on Saratoga Avenue thrived and are still there to admire today, thanks to Cobb’s wife. She had suggested that he plant Torrey pines on Saratoga Avenue above Sunset Cliffs Boulevard because that stretch of street had no landscaping.

In 1915, the Door of Hope, a home for unwed mothers, was built on a 10-acre site in Ocean Beach’s Collier Park. Initially operated by the San Diego Rescue Mission, it was taken over by the Salvation Army in 1931. In 1962, the Door of Hope moved to a much larger facility in Kearny Mesa.

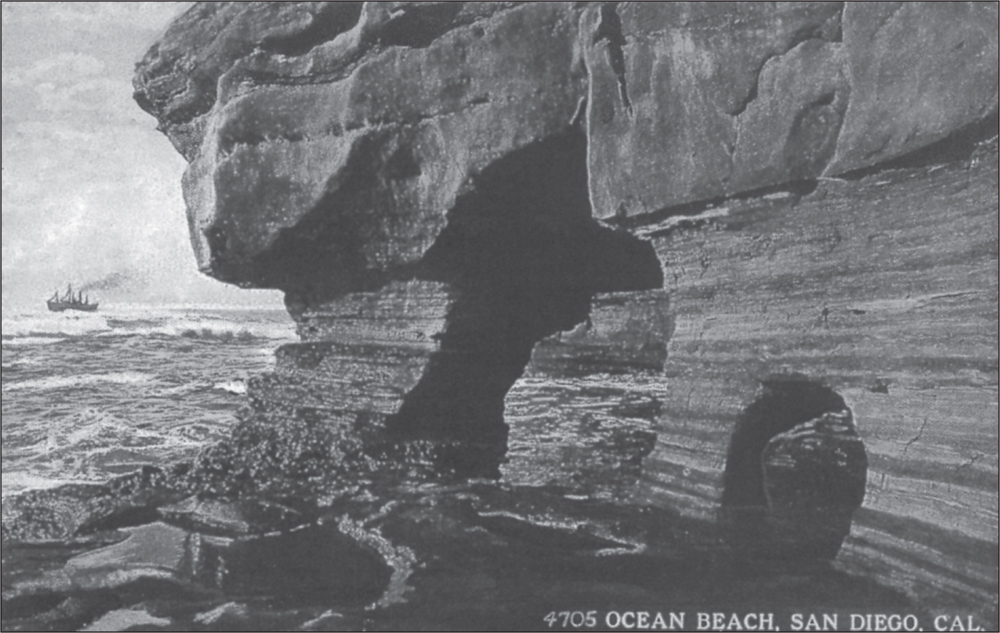

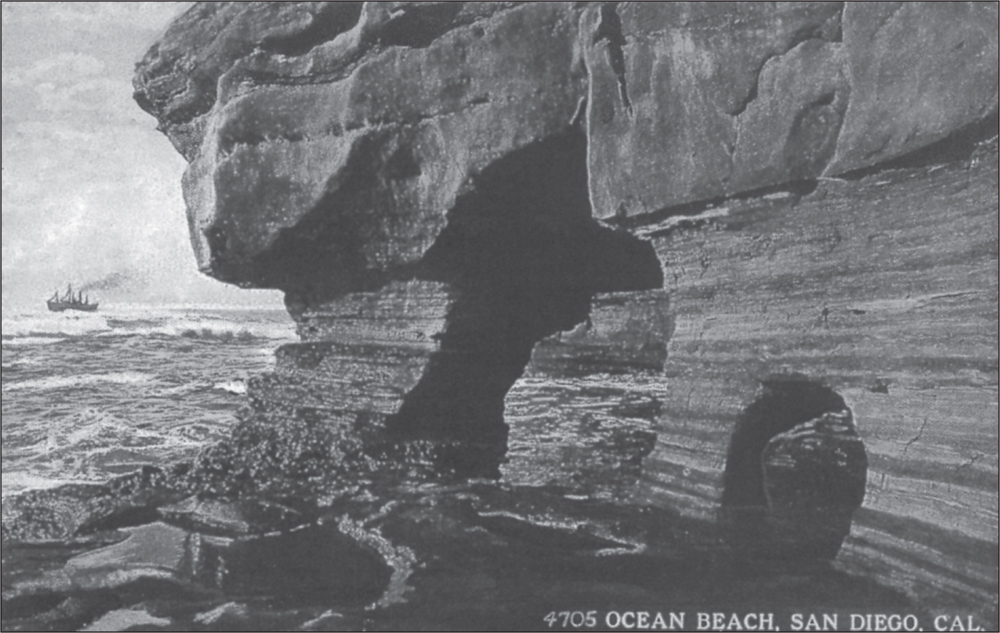

The picturesque sea arches and caves of Sunset Cliffs Natural Park are some 60 to 70 million years old. The collision of two tectonic plates (North American and Pacific) caused this ancient seabed of erosion-resistant but fractured sandstone to rise up out of the ocean.

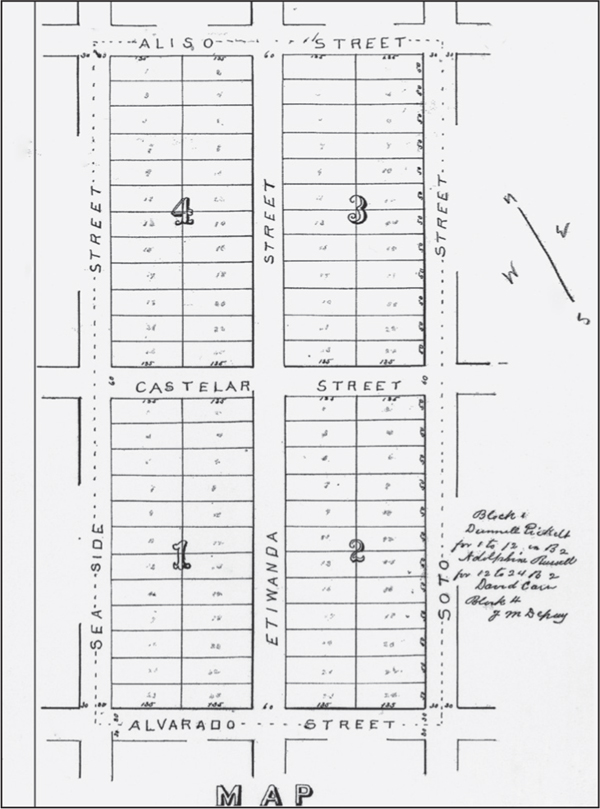

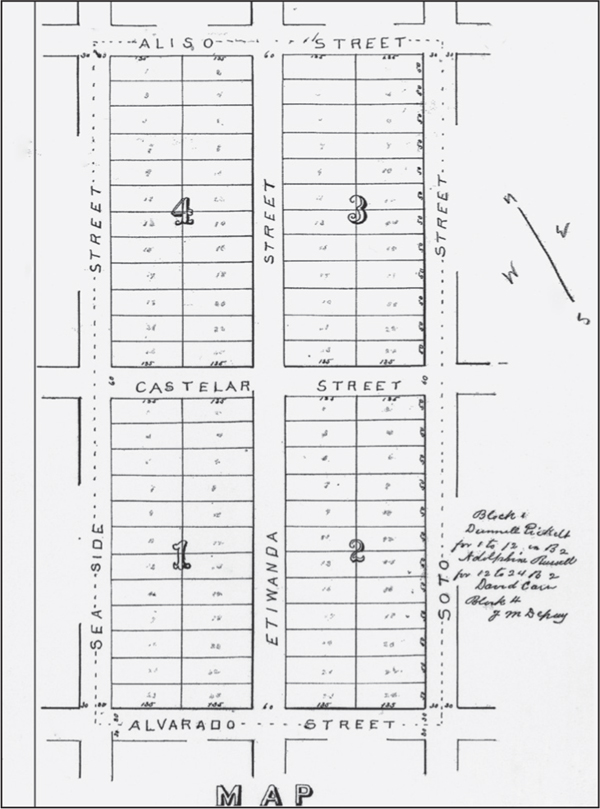

Carlson and Higgins were not the first developers to file a subdivision map in the Ocean Beach area. That honor goes to J.M. DePuy, who in 1885 filed a map (pictured) for an area known simply as DePuy’s Subdivision. (Ocean Beach had not been named yet.) Except for Aliso Street (now Valeta) and Alvarado Street (now Greene), these street names in the northern part of the community remain the same today. Unfortunately, things did not go well for DePuy, and he abandoned his business venture early. (Courtesy of County of San Diego.)

The 1984 Ocean Beach Christmas Parade featured a new marching group with the longest name of any entrant ever. The Ocean Beach Geriatric Surf Club Precision Marching Surfboard Drill Team and Gidget Patrol received loud applause and went on to entertain crowds at countless parades and performances around the country and also appeared in Hollywood videos, movies, and television commercials. The only rules to be in the club were: “You must surf, you must be over 30, and you can’t be trusted.”

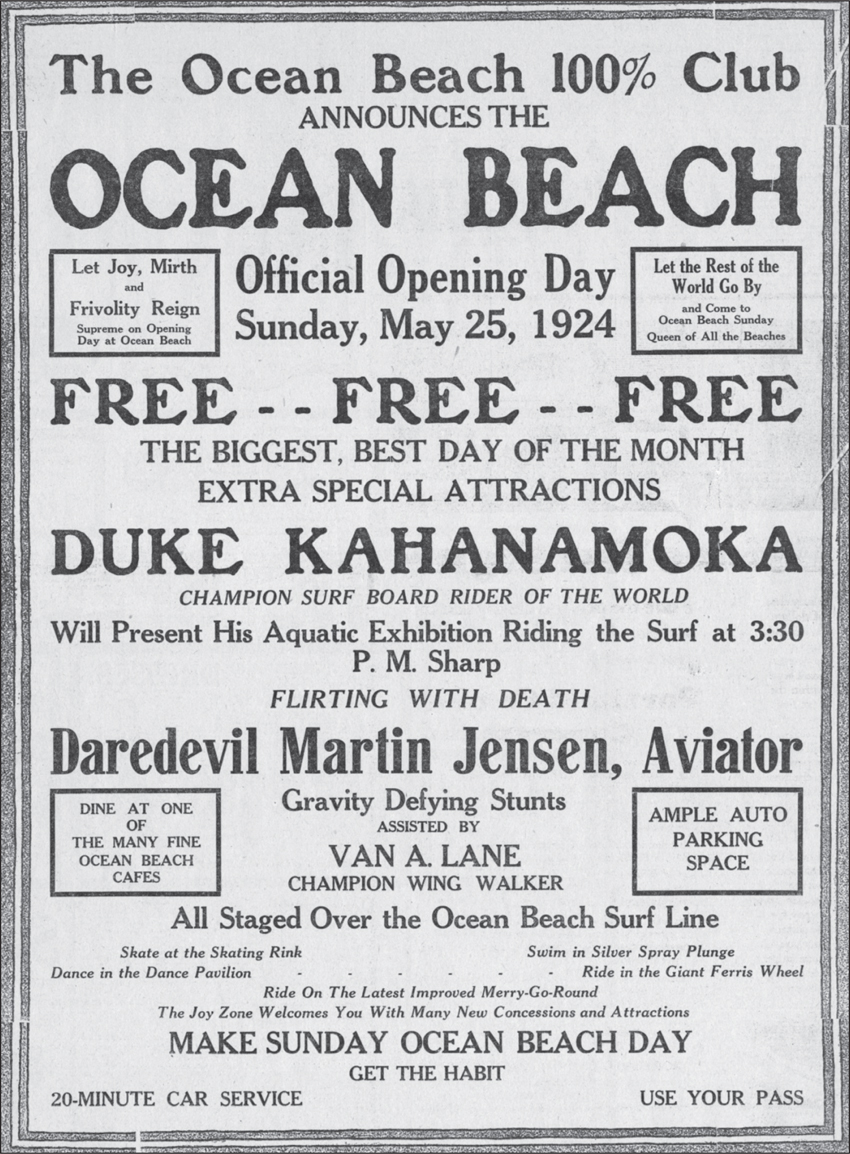

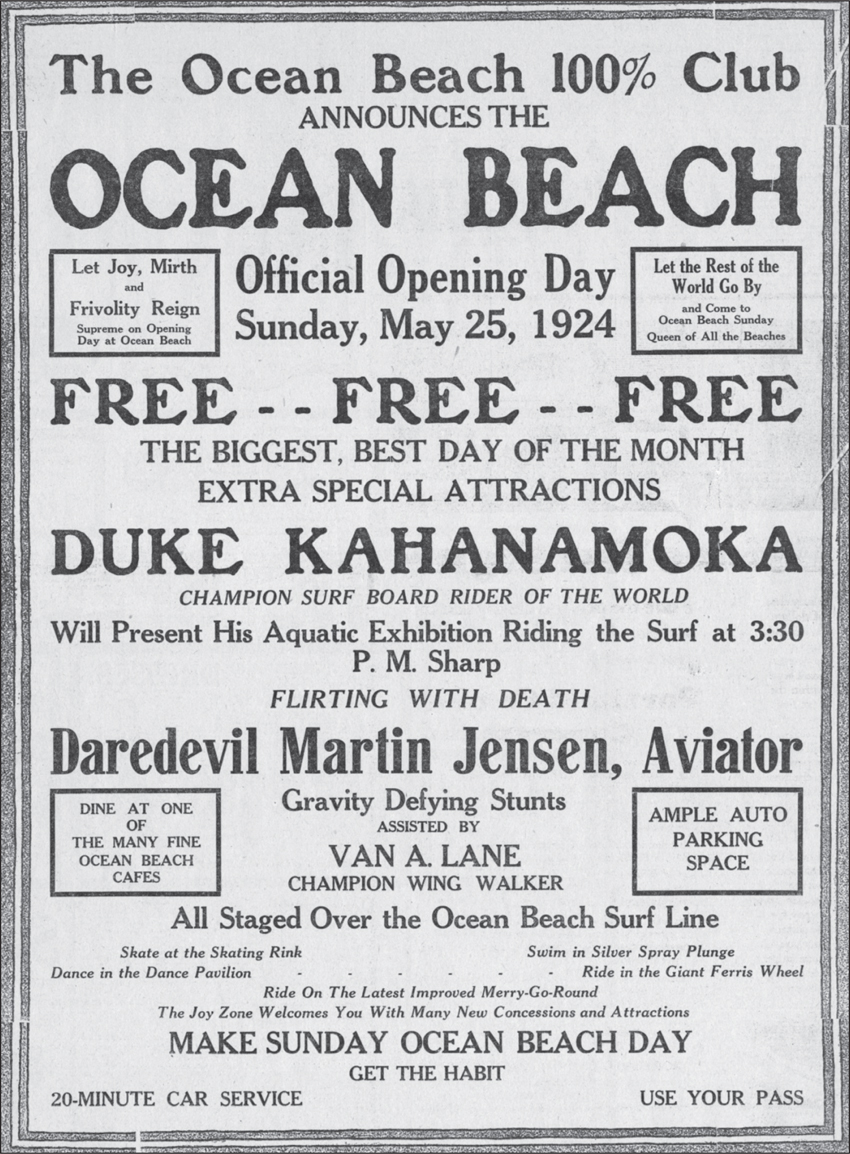

In 1924, Hawaiian Duke Kahanamoku (whose last name is misspelled on this poster) came to Ocean Beach to give a surfing exhibition. The appearance by the champion surfer and Olympic gold medalist in swimming was one of the events scheduled for the official opening day of the summer season. After drying off, Duke attended the Hawaiian Nights Fete at the Benbough dance pavilion, where he was guest of honor. According to Ruth Held’s Beach Town, Kahanamoku had first visited Ocean Beach in 1916, at which time he “gave a notable exhibition on a wide wooden board, standing up and riding the waves in to shore.” Other early demonstrators of this now popular California sport were members of the Hawaiian Village compound at the 1915–1916 Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park. Having been stationed at the exhibit so long that they had become rusty at their sport, the Hawaiians traveled across the bay to ride the surf off Coronado’s Tent City.

This six-foot bronze statue on the beach at Abbott Street and Santa Monica Avenue was installed in May 2013 as a tribute to Ocean Beach’s lifeguards. A nearby plaque recalls a 1918 tragedy in which 13 swimmers drowned at Ocean Beach when caught in a strong rip current. The four lifeguards on duty that day averted an even greater tragedy by rescuing, with the help of several civilians, 60 others who were struggling in the undertow. (Courtesy of Steve Rowell.)

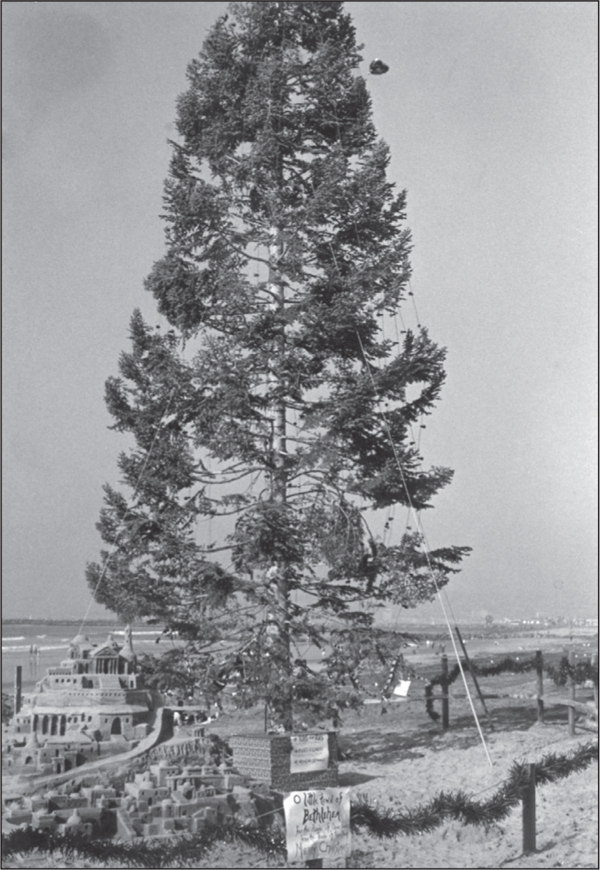

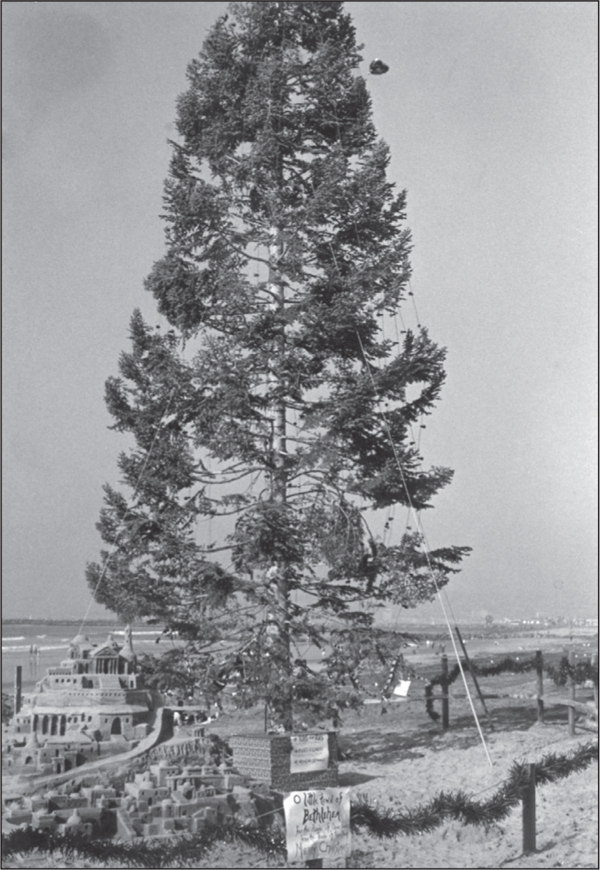

The Christmas season does not begin in Ocean Beach until the tree goes up at the foot of Newport Avenue. This tradition started in 1980 when Rich James, his brothers, and a few friends made a gift to the community of a tree brought down from Mount Shasta. The tradition continues with an Ocean Beach resident or group donating the tree each year, sometimes coming from a person’s own yard. Students from Ocean Beach Elementary (along with Santa) do the decorating. The first community Christmas tree in 1980 inspired the citizens of Ocean Beach to put together a makeshift kazoo band (below) and start another tradition—the Ocean Beach Christmas Parade, still going strong three decades later.

Ocean Beach little leaguer David Wells (left) grew up to be a big leaguer with the New York Yankees. On May 17, 1998, the Point Loma High grad pitched a perfect game against the Minnesota Twins in Yankee Stadium. Surprisingly, he was not the only kid from Ocean Beach to pitch a perfect game in a Yankee uniform in Yankee Stadium. Don Larsen (right), another Point Loma High grad playing for the Yankees, not only pitched a perfect game 42 years earlier, but he did it during the 1956 World Series. A mathematician computed the odds of two pitchers from the same high school pitching perfect games for the same team in the same stadium: 96 billion to 1!

Ocean Beach has several flocks of beautiful wild parrots, mostly of the Amazon Green and Mexican Red-Headed varieties. How the birds came to Ocean Beach is something of a mystery. One story has it that several birds were released when a house caught on fire, and they multiplied in the wild. The parrots are not shy about making their presence known. Just two parrots can make enough noise to cause conversations to stop. (Courtesy of Steve Rowell.)

It was called Collier’s Shack, but in the early 1900s, D.C. Collier’s home in Ocean Beach was a spacious modern dwelling with many innovative features, including a “cement plunge” (swimming pool), possibly the first in San Diego. The original house that Collier built in 1887 was a two-room bungalow, but he kept expanding it, adding a sun porch here and a bedroom there, until eventually it could sleep 16 people.

After Wonderland, Ocean Beach’s amusement park, went out of business, two buildings that had served as the park’s offices were moved to the corner of Lotus and Abbott Streets, where they were placed side by side and remodeled into an apartment building. There are still apartments at this site, but due to renovations and additions over the years, it is difficult to spot the old buildings.

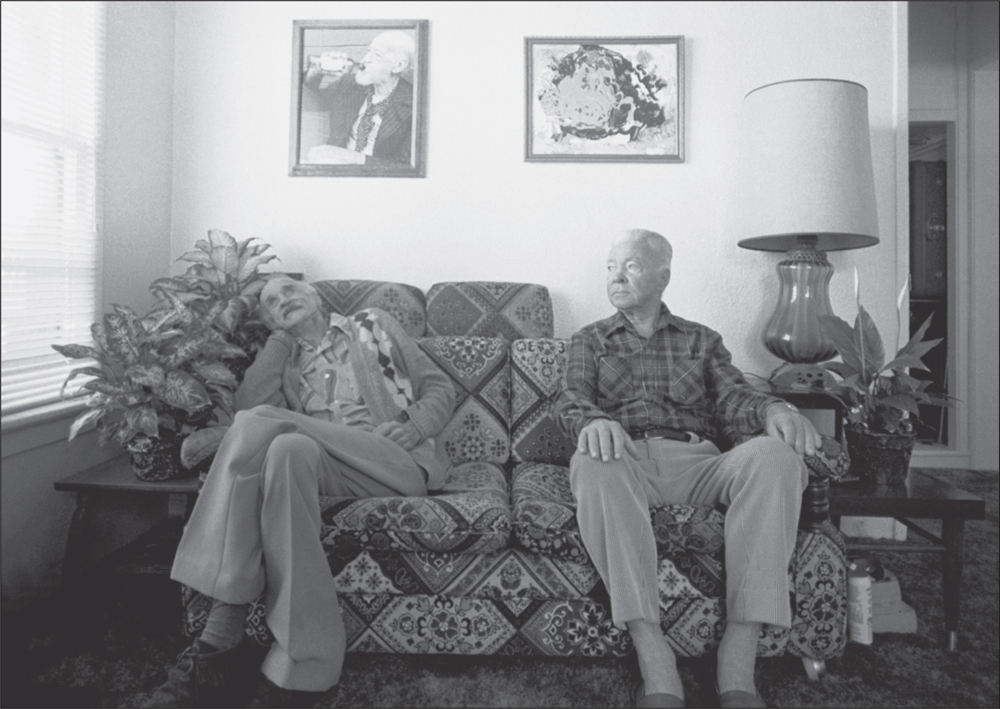

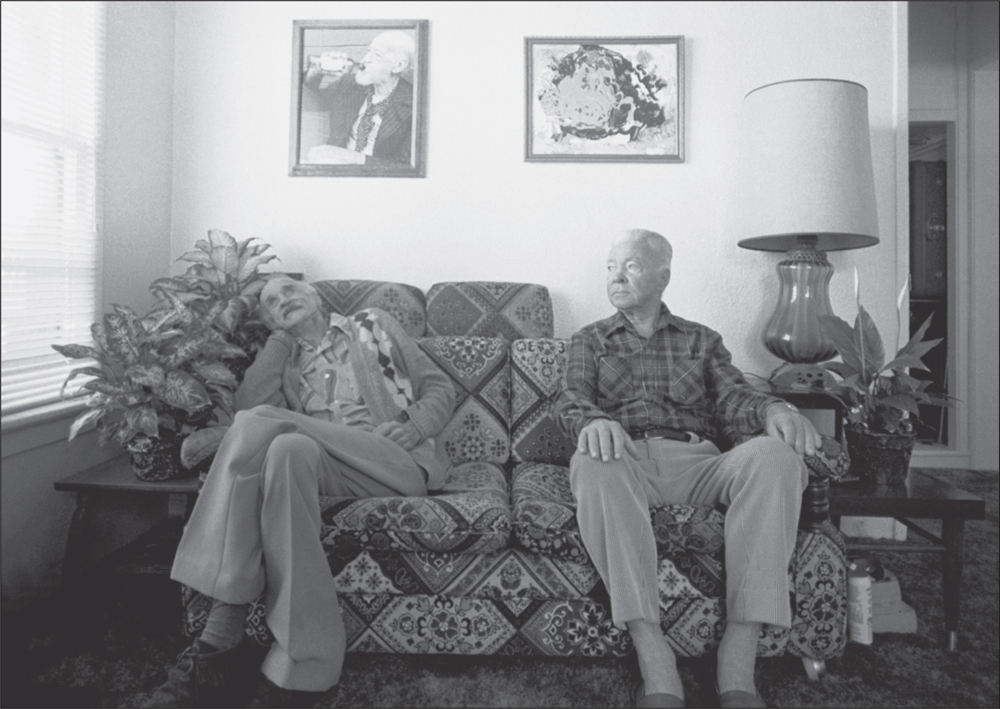

One of Ocean Beach’s most memorable characters was artist Clint Cary (1909–1993), also known as “The Spaceman of Ocean Beach” (left). Clint gained this nickname after having claimed that he had twice traveled with extraterrestrials to the planet Rillispore in the galaxy of Rigel. Inspired by these journeys into outer space, Clint began creating colorful pieces of cosmic art, which today are valuable collectibles. He also began passing out “Spaceman Cards,” each with a number that represented the recipient’s place in line for the next spaceship to Rillispore. Cary had a plan: When the world came to an end, two spaceships would arrive from Rillispore to transport the chosen ones to their new distant-planet home. Seated on the right is jazz musician Bob Oaks, another legendary character of Ocean Beach, who was a close friend of Clint Cary and a promoter of his art. Oaks lived in one of the cottages above the Ocean Beach pier, where for years he hosted Sunday night jam sessions featuring out-of-town jazz musicians. (Courtesy of Steve Rowell.)

Ocean Beach has held many a protest, especially since the arrival in the 1960s–1970s of many young activists, who eventually had a great influence on the group thinking of the beach community. In this c. 1970 photograph, Ocean Beach residents are picketing the local Bank of America because they saw it as a large corporation that was benefiting from the Vietnam War through its ties to the defense industry. Speaking out for what is right for the world in general—and Ocean Beach in particular—is an idea that goes back many years. For example, in 1922, Ocean Beach sought a divorce from San Diego, citing as grounds the slow response of the city in repairing damages caused by heavy rains at the beach. Community leaders said that the City of San Diego was ill equipped to oversee a summer beach resort, likening it to Los Angeles trying to run Long Beach. However, the idea did not get enough backing to be placed on the ballot, and Ocean Beach remained a part of the city.

American artist Mike Dormer of Ocean Beach gained fame in the surfing world with his creation of “Hot Curl,” a six-foot-tall, 400-pound concrete statue that was installed at Windansea Beach in La Jolla, a mecca for local surfers. The goofy-looking surfer representation, which became widely famous, now resides in the California Surf Museum in Oceanside.

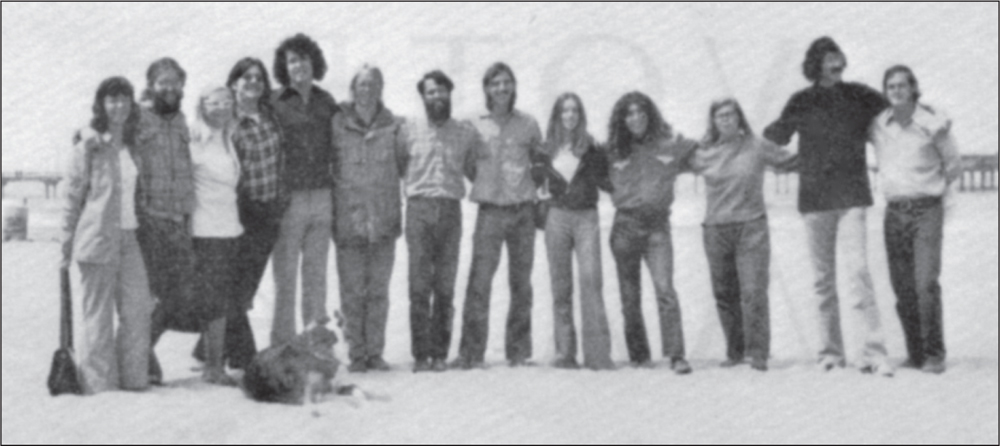

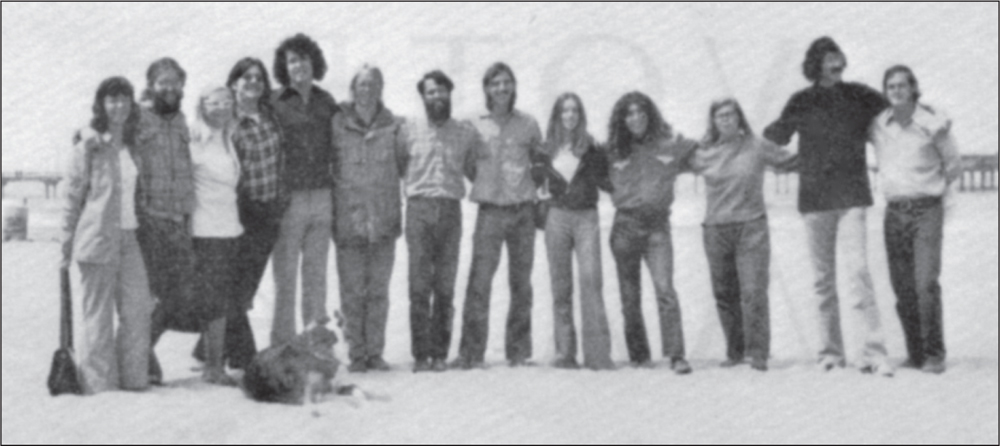

The Ocean Beach Community Planning Group, one of the first such groups in San Diego, was formed in the spring of 1976 by 14 activists. From left to right are members Maryann Zounes, Jerry Hildwine, Dolores Frank, Frank Gormlie, Lars Tollefson, Chris Bystrom, El Riel, Tom Kozden, Judy Czujko, Rich Cornish, Jill Mitchell, Doug Card, and Phil Elsbree (Norma Fragozo is not pictured). This group developed the first Precise Plan for Ocean Beach, which served as a blueprint for land use for over 30 years.

This former swim instructor at Ocean Beach’s Silver Spray Plunge made newspaper headlines in 1950 when she broke the women’s record for swimming the 23-mile English Channel set in 1926 by Gertrude Ederle. Florence Chadwick (1918–1995), the daughter of Ocean Beach policeman Richard Chadwick, broke many other long-distance swimming records, including some set by men, and was the first woman to swim the channel twice (both directions). In 1984, she was inducted into the San Diego Hall of Champions as the greatest long-distance swimmer in history. After retiring from competitive swimming, she worked as a stockbroker in San Diego and was vice president for First Wall Street Corporation. (Courtesy of San Diego History Center.)

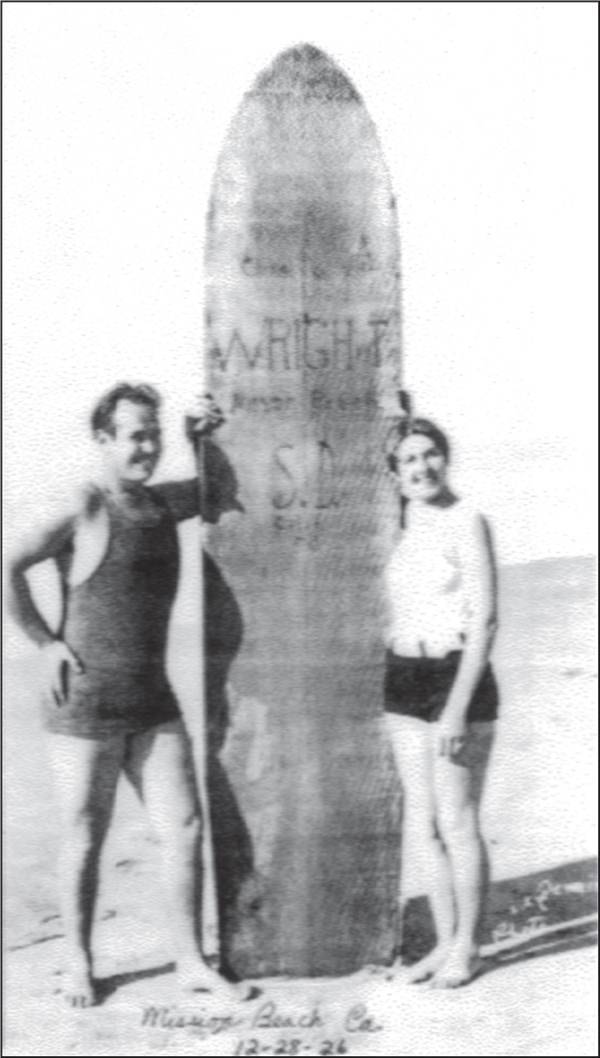

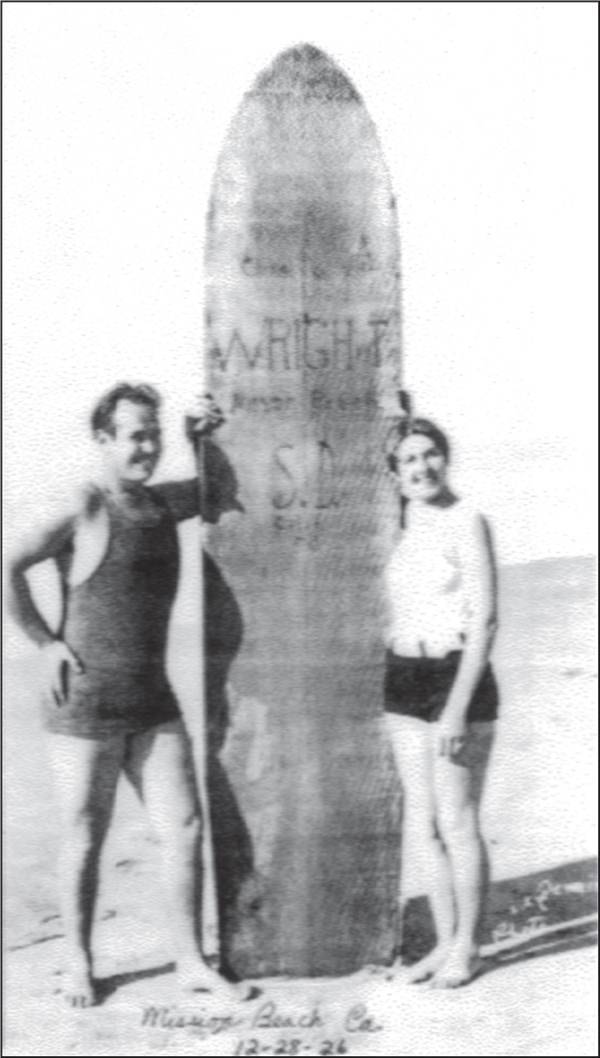

Faye Baird, a 1927 graduate of Point Loma High School, was one of California’s first women surfers. As a teenager, she learned to surf from Charlie Wright (left), a local disciple of Duke Kahanamoku. She first rode tandem with Charlie, but within a matter of days was riding a board on her own, thus earning her place in history as the first woman surfer in San Diego.

The entryway sign for Ocean Beach was first installed in 1984. When it needed to be replaced in 2012 due to wear and tear, the community was presented with multiple ideas for a new sign. But all of these suggestions were shot down, as OBceans overwhelmingly voted for an exact replica of the old sign, showing that some things just should not be tampered with.