ALTHOUGH THE NAZI EMPIRE had crumbled by April and the fatherland was being overrun by the Allies, Germany’s northern Baltic coast remained perhaps the safest place in the country. In addition to prisoners being transported to the Baltic, German civilians and important Nazi leaders fled to the coastal communities still under Nazi control, including Neustadt and Lübeck in Holstein. Unbeknownst to the Nazi commanders and prisoners arriving at the Baltic coast, a deal had been made in 1944 by C. J. Burckhardt, the president of the International Red Cross, and Allied commanders to spare as much of Lübeck Bay as possible from the bombing campaign because it could potentially serve to collect and evacuate war prisoners. Nazi officials therefore concluded that it would also be a good place to send the Cap Arcona and other large ships.

Nestled along the Baltic coast, the city of Lübeck functioned as a major seaport. Neustadt was a smaller, quieter community approximately eighteen miles northeast of Lübeck and thirty-one miles from the major seaport at Kiel. Brick warehouses, a small port, and fishing boats dotted the tree-lined shore. The tall spire of a church marked the center of the downtown. Had it been another time and altogether different situation, it would have been described as charming or quaint. Two bays—named for the towns—were visible from the shoreline. Neustadt Bay was about two miles wide and a bit shorter in length. It opened into Lübeck Bay, which was much larger and flowed out to the Baltic Sea.

The coast in the late winter of 1945 was abuzz with activity and anxiety. Neustadt had a naval base, which housed a submarine training school headed by Captain Albrecht Schmidt and the 3rd Submarine Division commanded by Heinrich Schmidt.aa Two smaller freighters waited at the port, while two massive ocean liners were anchored not far from the dock. In town people and soldiers rushed at a frenzied pace to abandon the area, knowing that the Allies were closing in fast.

By late April the scene at the coast was one of chaos. There were far too many prisoners arriving for the number of guards, amount of food and water, and facilities available at the harbor. Given the impossible situation and lack of clear orders, the SS guards were not sure what to do, nor were they told what was happening. The only news that arrived at the coast told of Germany’s dire situation, yet the guards did nothing to help any of the prisoners. As a result, some of the prisoners arriving at the coast were so weak that they died while waiting at the harbor. In this tense situation, rumors swirled among the guards and prisoners. Some suspected that Nazi leaders and soldiers would try to flee to German-held Norway to establish a final redoubt. However, the Cap Arcona, the largest transport ship gathered at the bay, was in no condition to set sail, and there were far too many prisoners, soldiers, and civilians in the area to fit on two large liners.

Another rumor was that Count Folke Bernadotte, operating on behalf of the Swedish Red Cross, was at the coast, trying to rescue prisoners. However, as one historian explains, “Some of the seamen on the Cap Arcona were told that the prisoners were to be taken out to sea and then collected by Swedish Red Cross ships, but this assurance was probably a means of allaying their fears.” Word also spread at the port that Heinrich Himmler was involved in secret peace negotiations in late April. This gave rise to yet another rumor—that the prisoners were to board ships to be handed over to the British. During the war-crimes tribunals afterward, the provincial governor of Hamburg, Karl Kaufmann, testified that the prisoners were to be taken to Sweden.

There was a more gruesome rumor. Georg-Henning Graf von Bassewitz-Behr, head of the SS in Hamburg, who was also forced to testify at the postwar trials, claimed the prisoners were to be killed “in compliance with Himmler’s orders.” All evidence of the Holocaust, he noted, had to be eliminated. Kurt Rickert, who worked for Bassewitz-Behr, testified at the Hamburg war-crimes trial that the prisoners were to be loaded on the large ocean liners, and then the ships were to be sunk by a U-boat or Luftwaffe plane. Eva Neurath, a survivor of the death march and ordeal at the coast, testified at the postwar trials that she was told by a police officer that the ships were to be blown up.

THE LOADING OF PRISONERS onto the ships began on April 17. It was announced that prisoners waiting at the port would be taken from the docks to the two freighters and two larger ocean liners in the bay, but the process was anything but orderly. Absent any clear mission or direct orders, the chaotic situation devolved into shouting and threats from Kaufmann and protests from the ships’ captains.

The plan was to transport the prisoners from the port to the ships at anchor using the Athen, a 401-foot freighter built in 1936. With its single massive smokestack, the Athen was larger than the Thielbek, the other freighter at the port, but much smaller than the two ocean liners at anchor, the Deutschland and Cap Arcona. However, Fritz Nobmann, the skipper of the Athen, refused to allow prisoners to board his ship. After a short delay, the captain was threatened by the SS and told he would be shot. Nobmann backed down, and the first group of prisoners was violently herded onto the Athen. Over the next several days, the freighter would make repeated trips to and from the Cap Arcona and the other two ships.

Another confrontation occurred later that same day when Kaufmann ordered Johann Jacobsen, the captain of the Thielbek, to stand by for orders to take on prisoners from the docks. He too protested. The Thielbek, a freighter roughly 300 feet in length that displaced 2,815 tons, was in bad shape and unprepared to accommodate even a fraction of the number of prisoners gathered at the docks. Because it was a freighter it was not designed for passengers—it had only two holds and a handful of cabins. It had also been bombed the prior summer, and the repairs, conducted at Maschinenbau-Gesellschaft shipyards in Lübeck, its home port, were unfinished when it was called back into service. Both the rudder and the steering apparatus were not fully functional; the ship had to be towed by a tugboat into its present position at the pier. Captain Jacobsen was still waiting for new motors for his ship when the loading began.

Captain Heinrich Bertram of the Cap Arcona was also told to prepare to accept prisoners. The famous ship was no longer the celebrated ocean liner that carried elite passengers to South America in style; nor was it the ship commissioned by Joseph Goebbels and Herbert Selpin to star in the Nazi film about the Titanic. It had been painted a dull gray, and much of the elegant interior had long since been removed. Like the Thielbek, the three-funneled ocean liner was barely seaworthy and, despite its size, was ill-prepared to take more than a few hundred prisoners. The ship was low on sanitary facilities, had little food or water, and was completely defenseless.

Captain Bertram refused to follow the orders, claiming his ship was not equipped to hold prisoners and was no longer in military service. He wrote to Hamburg-Süd, the company that owned the Cap Arcona, complaining about the situation. “For me it was a matter of course to refuse to accept the prisoners, since any responsible seaman knows that the risk at sea to take on human beings without absolute necessity during wartime is dangerous enough, especially such masses.”

The Cap Arcona under construction in the Blohm + Voss shipyards in Germany, 1927

The Cap Arcona docked on one of her cruises

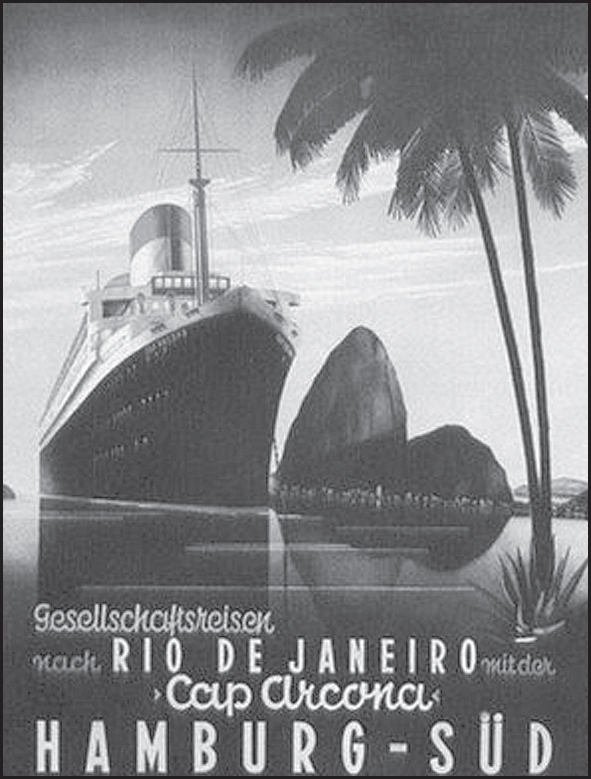

A poster advertising the Cap Arcona’s cruises to South America

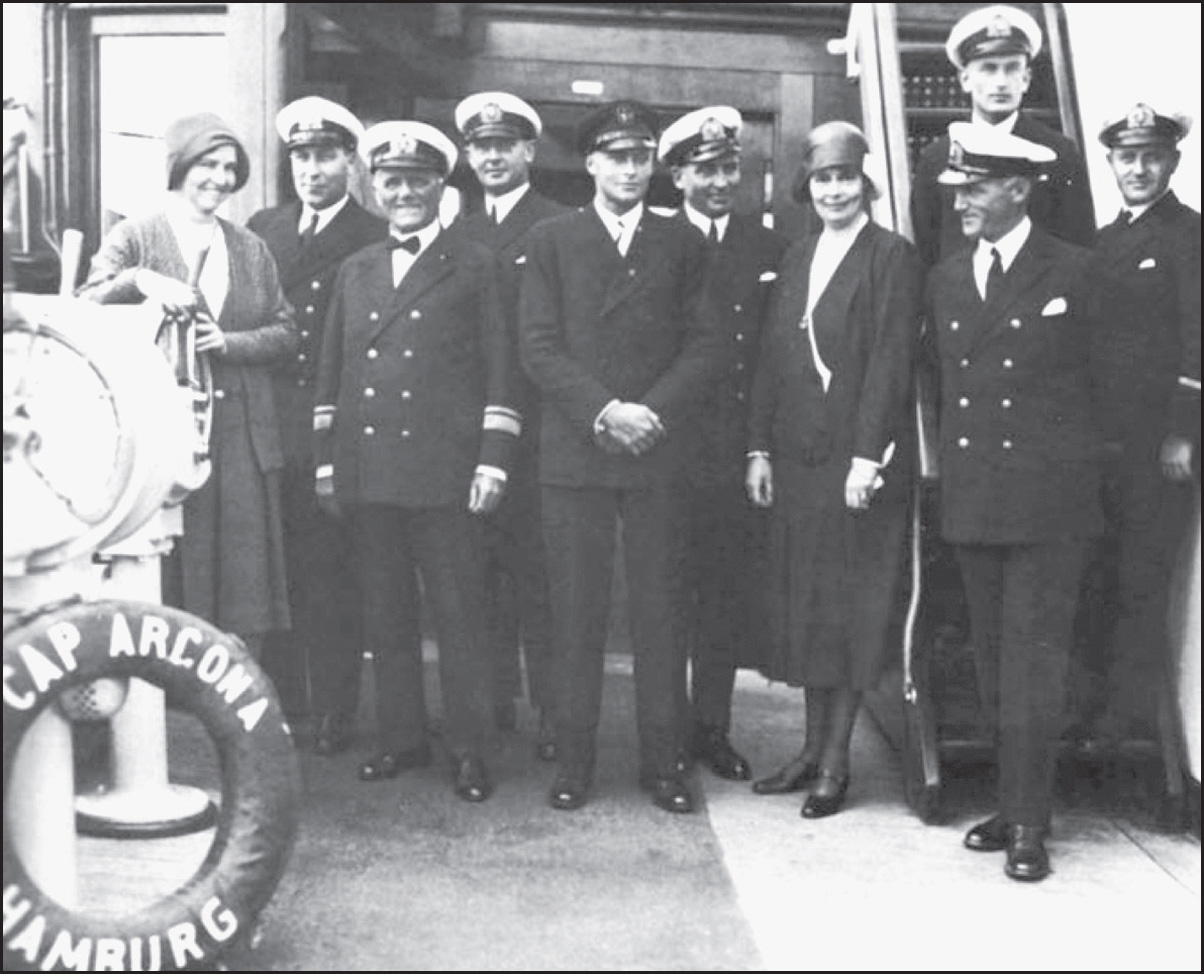

Distinguished passengers on board the Cap Arcona—Ernst Rolin and some of his officers pose next to Princess Cecilia of Prussia and her son Prince Federico. Heinrich Bertram, the second officer, is on the right

Two passengers from Brazil seated on the Cap Arcona’s deck

Adolf Hitler, who was passionate about large ships, poses with a group of sailors aboard the warship Deustchland (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, delivers a speech during the book burning in Berlin (National Archives and Records Administration)

Movie buffs Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels watching a film shoot

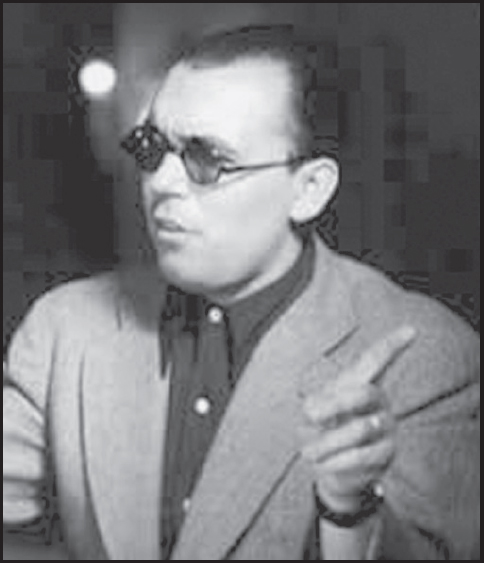

Herbert Selpin, the director of the propaganda film Titanic

Herbert Selpin on the set of Titanic (Filmmuseum Berlin—Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek)

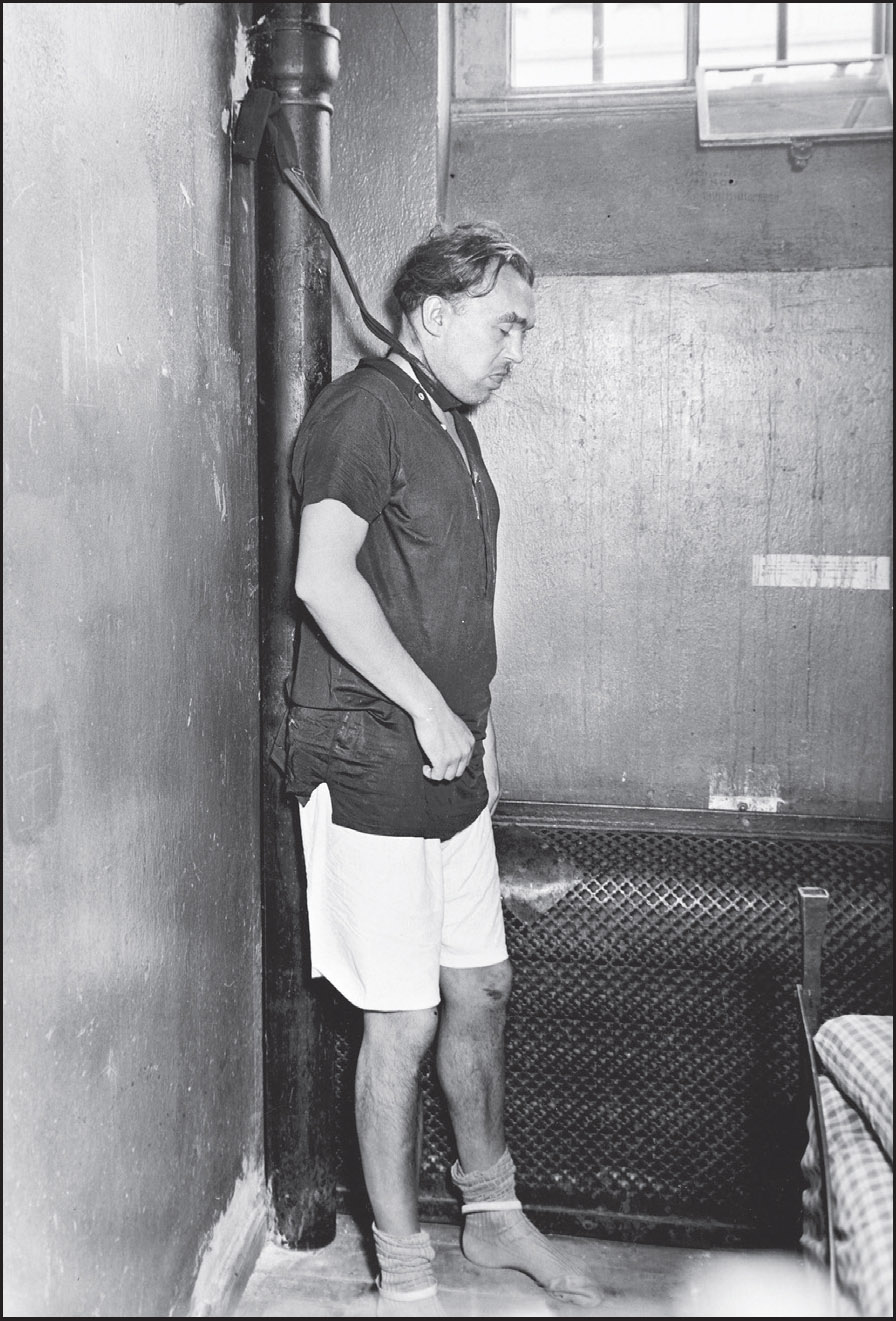

Herbert Selpin hanging in a jail cell in Berlin

Poster (in French) for the new German film Titanic

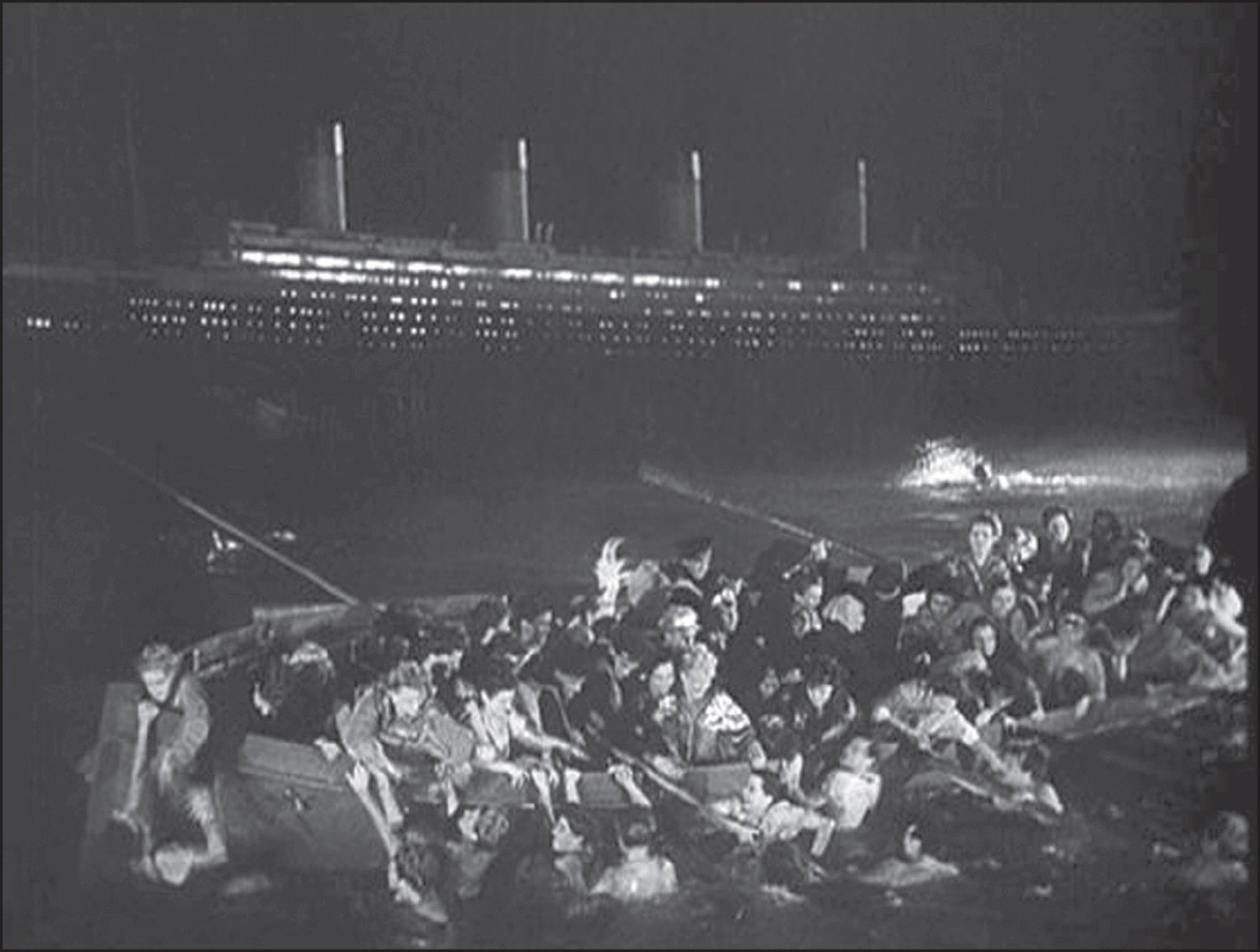

Scene of the Titanic flooding, from the film

The Titanic sinking and lifeboats, from the film, 1943

View of a section of the Neuengamme concentration camp after liberation, 1945 (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

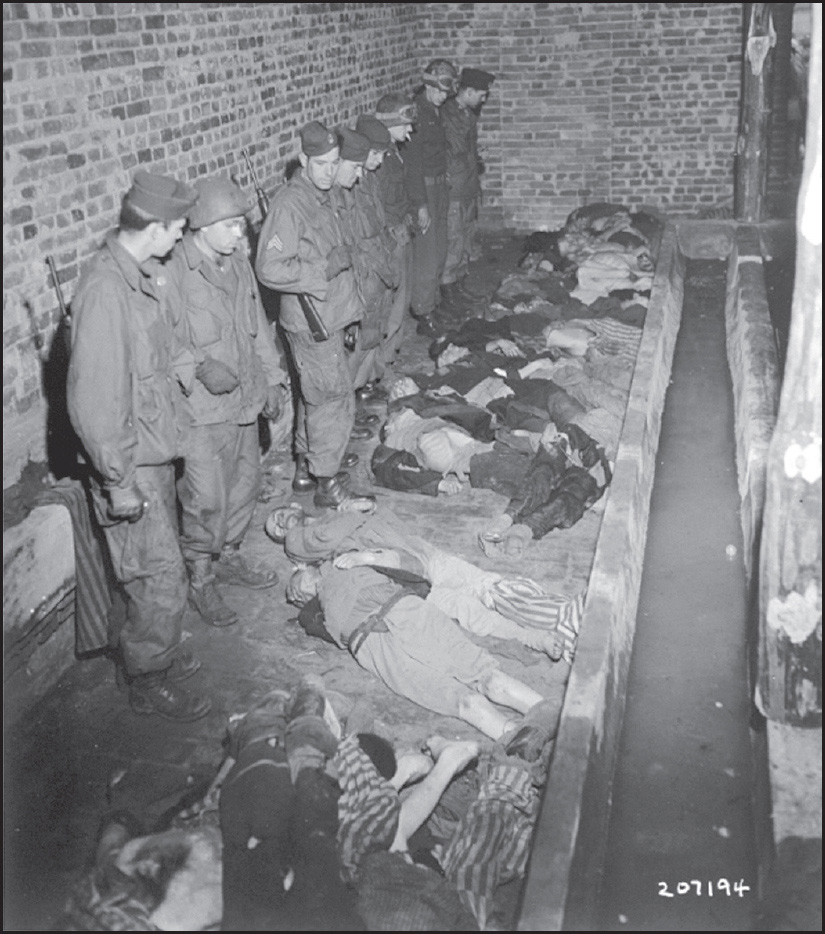

Troops with the American 82nd Airborne Division examine corpses found in the latrine of one of Neuengamme’s subcamps (National Archives and Records Administration)

Count Folke Bernadotte of the Swedish Red Cross with a convoy of vehicles from his “White Buses” campaign, 1945

The Cap Arcona painted a dull grey and rusting in port at Gotenhafen on the Polish coast

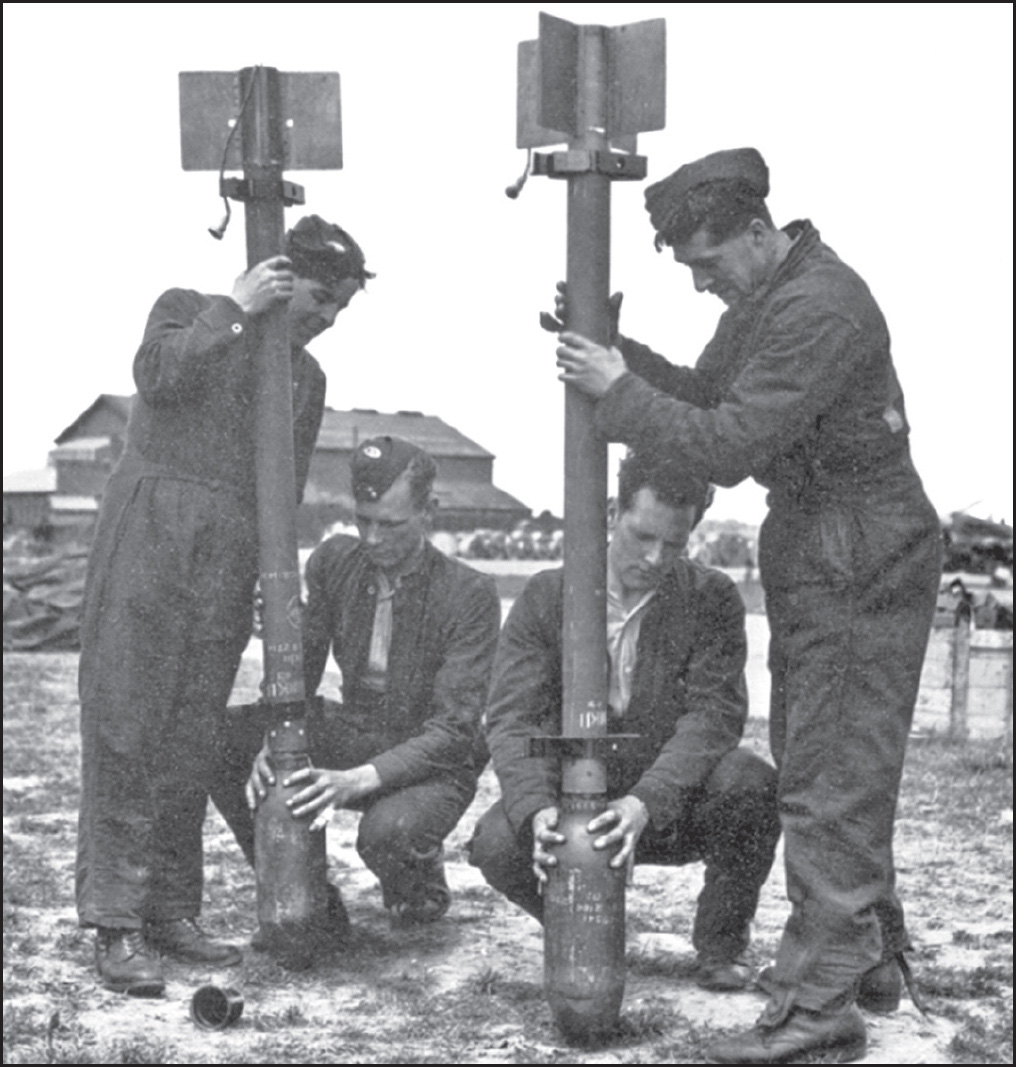

Airmen with a 60-pound rocket, the kind used to destroy the Cap Arcona, 1945

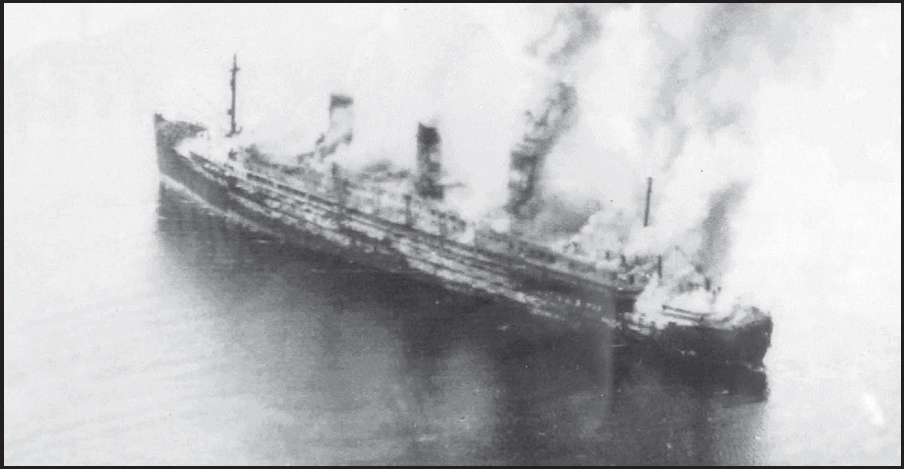

Typhoon fighter-bombers attack the Cap Arcona, 1945

The Cap Arcona on fire after the attack, 1945

The Cap Arcona capsized in Lübeck Bay after the attack, 1945

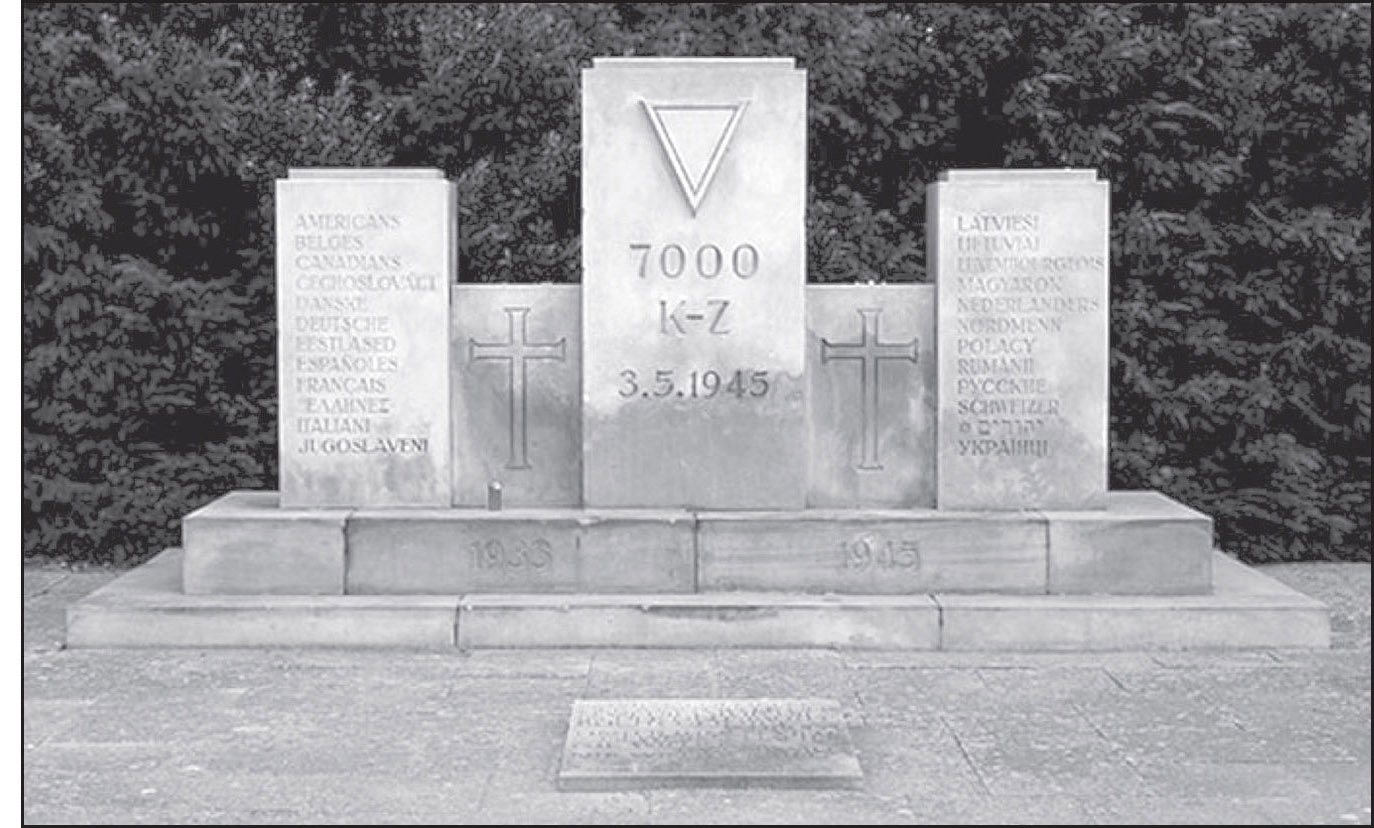

The marker memorializing the Cap Arcona disaster in Neustadt on Germany’s Baltic coast (The Cap Arcona Museum of the Municipality Neustadt in Holstein)

However, on April 18, SS soldiers boarded the Cap Arcona and Thielbek, and Captains Bertram and Jacobsen, respectively, were informed that they had to accept the camp prisoners on board their ships. After the SS soldiers departed the Thielbek, Captain Jacobsen, with Captain Bertram at his side, issued a warning to his officers of what was about to happen. “There is no way to keep it a secret: There will be concentration camp detainees coming on board soon. Captain Bertram and I refused to take detainees on board. However, there is going to be another meeting tomorrow.” Walter Felgner, the second officer on the Thielbek, survived the war to tell the story. He recalled that both captains remained resolutely opposed to the orders and were ordered to come ashore to meet with Karl Kaufmann.

The second meeting did not go well for the captains, but Captain Bertram did not give up. Still holding out hope that he could defy the order from Kaufmann and the SS, Bertram traveled to Hamburg to discuss the matter with Hamburg-Süd, the company that owned the Cap Arcona. He complained about losing command of his ship, the mission, and personnel issues.bb However, any hopes Bertram had that Hamburg-Süd could intervene on his behalf were dashed. When he returned to Neustadt the next day, April 20, he and Captain Jacobsen of the Thielbek again met with Kaufmann, but were informed that concentration camps in the region were being evacuated and at least 10,000 more prisoners from Neuengamme were on their way to join the thousands already at the coast, and all were to be loaded onto their ships.

Kaufmann reminded Bertram and Jacobsen that he was not only the provincial governor but was also the Reichskommissar with authority over shipping. The Cap Arcona and Thielbek would be accepting thousands of prisoners whether the captains cooperated or not. Another ship, the Deutschland, a converted hospital ship, would likely be forced to accept prisoners as well. If the captains refused, Kaufmann informed them that they would be stripped of command and shot on the spot.

Captain Jacobsen again met with his officers aboard the Thielbek. Visibly depressed, he complained, “Starting today, I’ll have no command over my own ship anymore.” The Athen began transporting prisoners to the Thielbek and Cap Arcona.

Loading resumed on April 20. That same day another 2,500 prisoners arrived at the port. Max Pauly, the commandant of Neuengamme, had also sent his chief officer, Major Christoph-Heinz Gehrig, to Lübeck Bay to oversee the transfer of prisoners to the ships. The captains aboard the prison ships came to realize that this operation was a priority to Kaufmann and that something was about to happen. The man that Kaufmann dispatched to supervise the loading had a reputation for being especially vicious. Indeed, Gehrig had been responsible for killing the children used for the tuberculosis tests at Neuengamme and the nearby Janusz-Korczak School at Bullenhuser Damm. He remained just as ruthless in his new task, threatening to kill the captains and crew of the ships if they disobeyed his orders. And so he ordered that Captain Nobmann of the Athen transport the 2,500 newly arrived prisoners to the Cap Arcona, along with 280 guards to prevent any resistance.

But when the Athen arrived to tie up next to the Cap Arcona, the prisoners were unable to be transferred to the larger ship. Captain Bertram had again gone ashore to try to negotiate to save his ship and had given orders to First Officer Felgener to allow no prisoners on board the old liner. The Cap Arcona was so large and its decks so high off the water that it was logistically difficult to transfer prisoners from a smaller ship without the full cooperation of the Cap Arcona’s crew. Despite the complaints and threats by the SS guards on the Athen below, First Officer Felgener simply refused to lower the ladders and gang planks. Felgener realized the hopelessness of the situation and informed his fellow officers that it was only a matter of time before the ship would become a “floating concentration camp.”

The Athen remained next to the large liner all night, its captain not sure what to do and leery of reporting to Kaufmann or Gehrig that he had failed in his mission. In the morning the captain gave up and sailed the freighter back to port with all twenty-five hundred of the new prisoners still aboard. A convoluted series of communications, protests, and orders then ensued. It started when Gehrig saw the Athen docking with the prisoners on the morning of April 21. He was furious and immediately notified Commandant Max Pauly. Together, they also reported the problem to the provincial governor and head of the Gestapo in Hamburg.

It took five days of bureaucratic bickering, but orders were eventually transmitted back to Gehrig. They stated that the loading of prisoners must proceed no matter what. Kaufmann, the governor, dispatched additional men to enforce the order and notified John Eggert, chair of the board of directors at Hamburg-Süd, reminding him that their ship was now under his control and that any further attempt to try to secure the Cap Arcona would not be tolerated. On orders from Kaufmann, Gehrig impounded the Cap Arcona on April 26.

Captain Bertram was met at the harbor by Gehrig and SS officers carrying machine guns. Bertram described the situation on April 26. “Gehrig had brought a written order to my attention for me to be shot at once if I would further refuse to take the prisoners on board. At this point it became clear to me that even my death would not prevent boarding of the prisoners, and so I informed the SS officer that I categorically declined any responsibility for my ship.”

Soon afterward, the Athen sailed back to the Cap Arcona filled with prisoners, minus those who had perished during the wait. Bertram stepped aside but instructed the officers and crew of the Cap Arcona that they were not to mistreat any of the concentration camp prisoners who boarded the ship. The Cap Arcona and its sister ships were now floating concentration camps.

On board, the crews scrambled to ready the ships. Provisional toilets had to be set up on the deck of the Thielbek. The entire process of transferring the prisoners from the harbor to the ships was further hampered by the fact that the mariners and SS guards did not like or trust one another. The crews were outraged by what was happening to their ships and alarmed by the savagery of the SS guards toward the prisoners.

The twenty-five hundred prisoners from the Athen were crammed into the Cap Arcona’s holds and rooms. Major Gehrig informed Captain Bertram that more prisoners were coming and that he was expected to accommodate as many as seven to eight thousand of them. Bertram complained that it was impossible to accommodate that many, given his skeletal crew, lack of food and water, and general poor condition of the ship. Bertram had been making this argument for days, so Gehrig and his SS guards decided to see the conditions for themselves. What they saw shocked even them.

The ship was in deplorable condition, and the stench of human feces from the toilets that had long since ceased to function was overwhelming. Dead bodies littered the holds and had to be removed. Still, the bureaucratic-minded Nazis recorded the deaths and identities of as many prisoners as possible. One of them was Jelis Laskovs, a twenty-year-old Polish Jew, who, according to Nazi records, died on April 27 of diarrhea. The Nazi officers reluctantly agreed that the scheduled number of prisoners was too high, but also maintained that the ship must take on some additional prisoners. Commandant Pauly from Neuengamme sent an order that Bertram had to accept three thousand more prisoners. Bertram acquiesced, but announced that he refused to accept responsibility for what happened and attempted to leave the ship. However, the captain was stopped by Gehrig, who ordered two SS guards to detain Bertram and shoot him if he tried to leave. One of the SS troopers stuck a pistol in Bertram’s chest, causing the captain to step aside, saying, “I have a wife and two children. That is the only reason why I will comply with this insane order.”

From that point onward, the transfer of additional prisoners to the Cap Arcona continued without interference. Additional SS guards arrived on the Cap Arcona for sinister purposes. They began removing all life vests, life jackets, and anything else such as wooden benches that might float. These items were locked in storage, and then the guards began punching holes in the twenty-six lifeboats and landing crafts. These cruel acts were surely not lost on Captain Bertram and his crew, who likely began to figure out the mission planned for their ship.

Transferring weak and dying prisoners from one ship to another proved to be no easy task. Frustrated by the difficulty, the SS guards kicked and beat the prisoners while trying to load them onto the Athen and then onto the Cap Arcona. When the freighter tied up next to the Cap Arcona, flimsy ladders were thrown over the side of the tall ship, but the malnourished and weak prisoners had a difficult time trying to climb them. Those prisoners unable to climb were shot. One Polish prisoner remembered the ordeal in vivid detail. “They drove us on board the ships with shouts and blows. We climbed down steep ladders into holds. In the rush, many prisoners fell from a great height into the depths of the hold and were severely injured, suffering contusions and breaks. We could hardly move below. It was dark, cold, and damp. There were no toilets. No water. It began to stink.”

Once the prisoners made it up the rope ladders and onto the Cap Arcona, they were gathered on the Promenade Deck, where only a few years earlier passengers boarded the ship to toasts of champagne. As the prisoners shuffled in bare feet down the halls and stairs of the ship, they glimpsed signs of the splendor of the Cap Arcona’s glory days that the SS guards had failed to remove—brass railings, bronze ornaments, mahogany tables, and elaborate tapestries. They were marched across Persian carpets and through the Victorian dining room, usually at the end of a cracking leather whip, and locked into crowded rooms stripped bare of any amenities.

The SS guards occupied luxury suites on the upper decks of the Cap Arcona. From time to time, they received another kind of visitor. Women were brought aboard by small launches. These included girlfriends among the local women and prostitutes. German prisoners were put in the first-class cabins; Poles and Czechs in the second-class cabins; French, Italian, and Dutch prisoners in the third-class rooms; and Soviet soldiers and Jews were forced into the cargo and storage holds in the deep bowels of the liner, an area known as the “banana deck” and easily containing the worst conditions on the ship. One Jewish prisoner recalled being in a supply room well below sea level that was roughly twenty-five yards long by ten yards wide, packed full of survivors from Neuengamme. There were no beds or facilities available to the prisoners. There was no place to bathe or sleep; there was no privacy.

For the prisoners in the deepest holds, there were no windows, and the hatches were kept shut, which denied the prisoners any fresh air or light. The only light they experienced was when the hatches were quickly opened during the initial days of captivity to pass down buckets with a little food and water. Those rations consisted of an inedible soup without any bowls or spoons. Much of it spilled out of the bucket and onto the urine-filled floors. Buckets were also lowered by rope to collect the feces and urine, which also spilled back out of the bucket while being pulled up to the deck. One inmate who survived recalled that when the bucket reached the hatch, “The thing tipped up, emptying its revolting contents on the heads of the prisoners who had gathered underneath for a glimpse of the open sky.”

Soon, feces and urine filled the floors. Prisoners attempted with desperation to wipe the feces and urine from their bodies and find a clean spot in order to sit down, but it was impossible and they were forced to sit and sleep in human waste. The stench was so strong that the guards eventually stopped opening the hatches altogether. Either way, the ship had run out of food and water.

Throughout the ship, typhoid fever and lice spread among the prisoners, and bodies began piling up in the rooms and on deck. The conditions and smell were now so awful on board the Cap Arcona that most of the SS guards complained and demanded to be taken off the ship. They were replaced by about two hundred old men from the Volkssturm (men over the age of fifty-five conscripted into the home guard). Some prisoners recalled that at least the daily beatings stopped when the SS guards abandoned the ship.

The conditions on the Thielbek were equally abysmal. A narrow side door was used to load the prisoners, and, because the guards were in a panic, they kicked and shoved the survivors onto the ship. The prisoners were forced into a central storage area that was so crowded that it was difficult even to sit down. A large tub in the center of the open room was used as a latrine by the prisoners, but it soon overflowed onto the floors, and the prisoners, like those aboard the Cap Arcona, were forced to sit or stand in the waste in pitch-black darkness. Here too the screams from the dying and terrified, along with the overpowering smell, were such that the guards only rarely opened the doors.

Aboard the Thielbek, Captain Jacobsen sent a letter to his wife, describing the abysmal and deteriorating situation. “The dead are removed from the [holds] every morning. We had five this morning. But because [so many are dying] . . . they are being picked up by boats, to be taken ashore. . . . [P]risoners of all ages from 14 to 70 and from ministers, professors, doctors, captains, to workers—all are represented. . . . The foreigners are forced to go and remain in the [holds]; they are not allowed on deck. They are crammed in like sardines.”

One of those prisoners crammed like sardines into the holds of the Thielbek was Frenchman Michel Hollard. One of the leaders of the French Resistance who had established the espionage ring Réseau AGIR, Hollard had played a vital role in providing the British valuable information on German military plans and the V-2 rockets. The dashing spy remembered his efforts to comfort fellow prisoners. “My friends, our turn has come to set out for the unknown. We are all afraid, and I must admit that the prospect is far from reassuring. Is not this the moment to show what sort of men we are?”

The French spy called his fellow prisoners together for a final prayer. Holding hands with one another, Hollard prayed, “Oh God, from the depths of our agony, we beseech you, whatever happens to us, protect, we implore you, our wives and children and guard them against all evil.”

At the port prisoners continued to arrive by the thousands, and the Athen continued shuttling them to the three larger ships. A few small launches and rafts were commandeered to expedite the process and assist the Athen. From April 27 to 30, roughly sixty-five hundred additional prisoners, mostly from Neuengamme, were loaded onto the Cap Arcona and Thielbek. On board the Cap Arcona, the number of prisoners swelled, and the ship soon ran out of food, water, and medicine. Prisoners were dying in alarming numbers. Some of them were thrown overboard, while others were taken by the Athen and smaller launches back to the port, where they were disposed of in mass graves.

And then something happened . . .

The Athen made its final delivery of prisoners on April 30, bringing roughly two hundred more prisoners from the Fürstengrube concentration camp. Since being brought aboard the Cap Arcona, the prisoners had been trying to form a rudimentary organization to communicate with one another and lobby the crew to share their food and water. Unbeknownst to the skeletal detachment of guards still on board, this impromptu prisoner organization had also managed to lower some inmates over the sides of the ship and into the water. Led by a few British prisoners, they recruited some Soviet soldiers to try to swim to shore. However, in the cold water, the fragile prisoners perished.

The prisoner organization was, however, successful in registering their complaints about the inhumane conditions on board. Captain Bertram responded by requesting that some of the prisoners on board the overcrowded Cap Arcona and Thielbek be permitted to go back to the port. Amazingly, the officers at the harbor agreed, and around two thousand prisoners from the ships—mostly French, along with a few Belgian, Dutch, and Swiss prisoners—were taken back to the port. They could not have known, but Count Folke Bernadotte and the Swedish Red Cross were back at the port, demanding additional prisoners be released.

One of those taken off the Thielbek was French spy Michel Hollard. He and his comrades almost did not cooperate, for they feared the worst. But when they arrived on the top deck, they were hosed down to remove the feces and urine and then taken to the port. There they were met by the count. The detainees were transferred to the Swedish ships Magdalena and Lillie Matthiessen. On April 30 the hospital ships departed for Sweden. Hollard, aboard the Magdalena, had miraculously survived.

On May 1 Captain Bertram met with the prisoner organization on board the Cap Arcona and their leader, German actor Erwin Geschonneck, to inform them of some long-overdue good news: Hitler was dead, and the prisoners removed from the ship the previous day were rescued by the Swedish Red Cross. There was hope.

![]()

a The Germans also had research facilities at the coast dedicated to developing new technology for underwater rescue, naval weaponry, and other military applications.

b The captain’s crew had been reduced from 250 to 70, which was an amount inadequate for the number of prisoners the ship was housing or for setting sail.