TWO

THE DYNAMICS OF

EMPIRE: PERSIA OF THE

ACHAEMENIDS, 485

Among these countries there was a place where previously demons had been worshipped. Afterwards … there I worshipped Ahura Mazda in accordance with Truth reverently.

from Xerxes’s ‘Daiva- Inscription’

THE PERSIAN EMPIRE was not only enormous in scale, it was also extremely heterogeneous and complex. Cyrus II ‘the Great’ (c. 559–530) and his son Cambyses (530–522), scions of the Achaemenid royal house, had carved out their vast empire by military conquest. But it was left to Darius I (522–486), a distant relative who shrewdly married Cyrus’s daughter Atossa, to establish it permanently on secure foundations of tribute collection and bureaucratic administration. His son and successor Xerxes (486–465) attempted to emulate his great father in expanding the Empire, by conquering and incorporating the Greeks of the mainland, but he failed dismally, thanks to the Spartans above all, and died by an assassin’s hand.

In our evidence for the mighty Persian empire and its dealings with Greeks lies an incurable paradox. We can read some of the Persians’ own official records, several of which I shall quote extensively, and we can more or less accurately decipher the formalized language of the monuments of the Achaemenids’ official art in their several palace centres. But for a contextualizing ancient narrative and an overarching explanation of Perso-Greek relations between 550 and 479 we cannot do without Herodotus. This is despite his undoubted shortcomings as a ‘scientific’ historian of the best modern type.* For example, although he did somehow gain access indirectly to some key Persian documents, he never learned Persian – or indeed knew any other language than his native Doric dialect of spoken Greek and the literary Ionic dialect in which he composed his Histories. One little token of his monoglottalism is his deeply erroneous, ethnocentric belief that all Persian proper names ended in ‘s’.

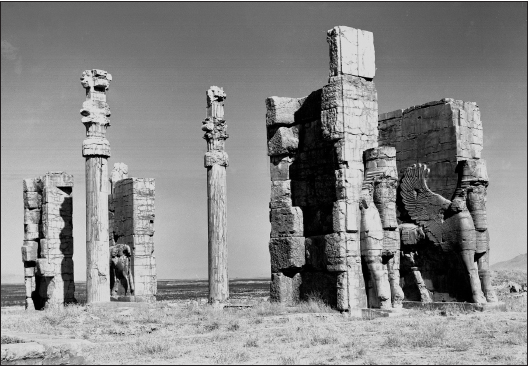

Of Mesopotamian derivation, these two colossal winged-bull effigies flank the East Door of the Gate of Xerxes at Persepolis and dwarf any human figures that dare pass through them.

On the other hand, before we get too carried away by Herodotus’s deficiencies as an observer, reporter, recorder and historian of Persia, we have to remind ourselves that even in the Greek world there was no Herodotus before Herodotus. Even more to the point, the inegalitarian, hierarchical, top-down Persian world of absolute monarchy and strict court protocol never produced a Herodotus at all. Achaemenid Persia had scribes, many of them, but not one historian. Scribes, paradoxically, made any less restricted form of literacy unnecessary as well as, probably, unwelcome. But bureacracy and a passion for counting have their advantages for the modern historian of ancient Persia. Now that we can read many official Persian documents, thanks largely to Henry Rawlinson who in the nineteenth century deciphered Persian cuneiform script, we can at least get an intimate feel for how the administration worked at the centre and for the immense ethnic diversity of this huge realm, the first truly world empire.

Consider, for example, the light thrown by the quite recently published Fortification Tablets from Persepolis on the career of a high official whose name in Persian was Parnaka but whom Herodotus transliterated as ‘Pharnaces’ (note that ‘s’). Thanks to Herodotus, we already knew quite a lot about his important son Artabazus. Here, for instance, are a few words from a context following the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE:1

Artabazus the son of Pharnaces was already a famous man in the Persian army and was further to increase his reputation as a result of the battle of Plataea [in 479].

This Artabazus, as readers had already been informed,2* was the commander of the land troops of Parthians and Chorasmians who fought in Bactrian war-gear. He receives several commendatory mentions in his own right from Herodotus. In stark contrast, his father Pharnaces appears merely as that – as the father of his (admittedly famous) son. Yet we now know – and this is one of the more spectacular discoveries made as a result of the decipherment of the Persians’ own official bureaucratic records – that Pharnaces had been no less distinguished than his son; in fact, in his way even more so.

For in the years around 500 BCE he had been the very highest royal official at the main ceremonial capital of the Empire, Persepolis (Parsa in Persian). We also know from his official seal that Parnaka was a son of Irsama (Arsames). Now, that Irsama/Arsames was a grandfather of none other than Great King Darius I. Parnaka/Pharnaces, therefore, was a brother of Darius’s father Hystaspes and the Great King’s paternal uncle. We already knew from Greek sources that Darius had made a clever dynastic marriage to Atossa. Now we see too how he exploited blood-relations to grease the wheels of the highest imperial administration. This is the sort of extraordinarily illuminating insight to be gained from the primary Persian documents available now to us – but never to Herodotus – directly in raw form.

As for the Empire’s ethnic diversity, there is no better means of direct access than via Darius’s boastful text recording his construction of a palace at Susa in Elam, the Empire’s principal administrative centre. Here is an extract from that long foundation charter:

This palace which I built at Susa: its materials were brought from afar … The cedar timber was brought from a mountain called Lebanon. The Assyrian people [of northern Iraq today] brought it to Babylon [southern Iraq]. From Babylon the Carians [from south-west Anatolia] and Ionians [Greeks of central west Anatolia] brought it to Susa. The sissoo-timber was brought from Gandara [Afghanistan–Pakistan border] and from Carmania [southern Iran]. The gold which was worked here was brought from Sardis [capital of the satrapy of Lydia, central west Anatolia] and from Bactria [northern Afghanistan]. The precious stone lapis lazuli and carnelian which was worked here was brought from Sogdiana [northern Afghanistan]. The precious stone turquoise … was brought from Chorasmia [central Asia]. The silver and the ebony were brought from Egypt. The ornamentation with which the wall was adorned was brought from Ionia. The ivory which was worked here was brought from Ethiopia, and from India and from Arachosia [southern Afghanistan]. The stone columns which were worked here were brought from … Elam. The stone-cutters who worked the stone were Ionians and Sardians. The goldsmiths who worked the gold were Medes and Egyptians. The men who worked the wood were Sardians and Egyptians. The men who worked the baked brick were Babylonians. The men who adorned the wall were Medes and Egyptians.

Darius sums up:

Darius the king says: ‘At Susa a very excellent work was ordered, a very excellent work was brought to completion. May Ahura Mazda protect me, and Hystaspes my father and my country.’

The great capitals located in the south of what is now Iran – Pasargadae (the original, built by Cyrus), Susa and Persepolis (‘a vast over-egged pudding of an archaeological site’, as one journalist has irreverently called it) – were complemented by a fourth at Ecbatana in Media, further to the north. That their public artwork was composed of materials from all four corners of the Empire we might have predicted; and likewise, if on a rather smaller scale, the sources of recruitment of the skilled workforce, including Ionians (Greeks) as in the Susa foundation charter quoted above. What is more extraordinary, however, is that out of this melange of disparate peoples and places each with their own distinctive cultural traditions was created a unified style, unique to the Achaemenids. Some would give Darius himself the credit for this, because it seems to presuppose a single controlling intellect, and this was an art focused on kingship (and without pretensions to global reach). But that may be to give him too much credit. Perhaps we should look rather for an anonymous Persian Imhotep* as the mastermind of genius behind the centrally linked building projects.

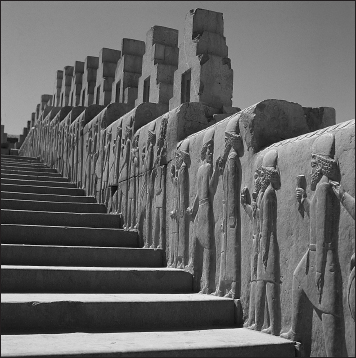

Achaemenid public art and architecture were also interestingly secular, in that no major religious monuments, of Egyptian or Babylonian type, for instance, were created. Their style was eclectic but coherent. For example, the Gate of Xerxes on the terrace platform at Persepolis, known also as the Gate of All Lands, was decorated, like the gatehouse at Pasargadae, with winged human-headed bulls. These were ultimately of Assyrian origin, whereas the distinctive Persepolitan column was derived from Egyptian and Greek models but arguably can be said to have surpassed both. However, the most stunning single building at Persepolis, still so today even in its ruined state, was the Audience Hall, the Apadana, closely parallel in its plan to that at Susa: a square columned hall with towers at the four corners and porticoes on three sides, the columns supporting double-bull capitals. What distinguishes the Apadana at Persepolis is the stone platform on which it is built. On the north and east sides this is decorated with staircases crammed with friezes of relief sculpture, each side a mirror image of the other. Repetition of motifs and forms – in this case showing the Persian Great King enthroned at the centre as processions of tribute-bearing subjects dressed in national costume from no fewer than twenty-three different peoples move towards him – was seen as a virtue by the Achaemenid rulers, since repetition conveyed the desired impression of power and inevitability. This Persian style was indeed the very reverse of an individualizing art form, such as that of the contemporary Greeks, though some of the masons at Susa did leave recognizable hieroglyph ‘signatures’ and some of the craftsmen there and presumably elsewhere were, as we have seen, Greeks. Another striking point is that, in sharp contrast to their Assyrian imperial predecessors, for example, scenes of warfare or hunting are absent from the walls of the Achaemenid palaces.

The Persians were related to the Medes and had succeeded them as imperial masters. They were not, however, more or less identical to each other, as the Greeks often fondly thought – they could even refer to the Persians as ‘the Mede’ in the singular. The Persians were the master people, as it were. There are no Persian tributaries in the procession scenes depicted on the Persepolis Apadana, but there are Medes: dressed in the distinctive Median garb of knee-length tunic (different from the usual Persian long, pleated dress) or long-sleeved coat (kandys), tight trousers (much scorned by the Greeks) and a cap with neck covering and ear-flaps; and bearing as tribute clothes, a short sword (akinakês), bracelets and vessels.

Originally this double bull-headed capital in grey marble topped one of the forest of columns supporting the roof of the Apadana at Susa.

This ethnic difference in the Iranian heartland was a microcosm of the heterogeneity of the Empire at large. Many different ethnic groups, many diverse creeds, many different languages jostled for living space under the Achaemenids’ imperial umbrella. What unified them administratively was that the central court and government insisted on a minimum annual contribution of tax and tribute in cash or kind, together with such military obligations as might from time to time be imposed either globally from the centre or at provincial level. The common linguistic currency of imperial administration and communication was Aramaic (the Semitic language spoken four to five centuries later by one Jesus of Galilee). But Darius also introduced a common monetary currency, the silver and gold coins known in his honour as ‘darics’. Darius was indeed the first living ruler to have his image – always represented as an archer with bow and quiver in a vigorous ‘running’ pose – placed on his coinage (the idea and practice of coinage were themselves only about a century old when he came to the throne). Plutarch, among his Laconian Apophthegms (Sayings of Spartans), preserves this anecdote:

In the Apadana (audience hall of the Palace) at what the Greeks called Persepolis (or Persae; Parsa in Persian) the Great King would receive annually, during the spring festival, tokens of submission and tribute from the subjects of his far-flung multicultural empire. Persepolis, founded by Darius I and further embellished by various successors, including his son Xerxes, was the empire’s main ceremonial capital, lying not far from where the kings were buried at Naqsh-i-Rustam tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam.

Alongside the steps of the grand staircase leading up to the Apadana (see above) members of the royal guard and officers of the court process in high carved relief.

Since Persian coinage was stamped with the image of an archer [Darius], Agesilaus said as he broke camp [in 394] that he was being driven out of Asia by the King [Artaxerxes II] with the aid of thirty thousand bowmen [gold darics].

The Achaemenid Persian empire’s founder was Cyrus II the Great (r. 559–529), and this is his simply designed but imposingly large tomb at Pasargadae, his home town and the empire’s original capital. Almost exactly two centuries after Cyrus’s death and burial, Alexander the Great of Macedon, the new King of Asia, learned that the tomb had been broken into and looted and ordered its immediate restoration.

For tax and military purposes, the empire was carved up in all into between twenty and thirty provinces, or ‘satrapies’ (apparently a Median word in origin), each governed by a satrap or viceroy; most satraps were drawn from the extended and extensive royal household (which practised the harem system). In Book 33 Herodotus provides a remarkable ‘catalogue’ of the Empire’s satrapies – twenty according to his reckoning – together with precise notations of the tribute in cash and kind that each was required to provide annually. From Persian documents we get an official listing of the chief peoples and lands over which Darius ruled, but not a satrapy list properly speaking:

By the favour of Ahura Mazda these are the countries which I [Darius] seized outside Persia … Media, Elam, Parthia, Aria, Bactria, Sogdiana, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Arachosia, Sattagydia, Gandara, Sind, Amyrgian Scythians, pointed-cap Scythians, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, Armenia, Cappadocia, Sardis, Ionia, Scythians from Across-the-[Black]Sea, Skudra, petasos [broad-brimmed hat]-wearing Ionians, Libyans, Ethiopians, men from Maka, Carians.4

One people absent from this tally is worth noting, the Jews of Judah. Three of the books of the Hebrew Bible, Ezra, Esther and Nehemiah, relate wholly and directly to the Achaemenid Persian period of Judaean history, though ‘history’ is not precisely what they deliver. Esther, it is thought, was written well after the Achaemenid Empire had come to an end, but it does nevertheless convey a powerful flavour of the perception the Great King’s more distant subjects had of life at the top in Susa:

The King made a feast unto all the people who were present in Shushan the Palace both unto great and small, seven days, in the court of the garden of the King’s palace; where there were white, green and blue hangings fastened with cords of fine linen and purple to silver rings and pillars of marble; the beds were of gold and silver, upon a pavement of red, and blue and white, and black marble. And they gave them drink in vessels of gold (the vessels being diverse from one another), and royal wine in abundance, according to the state of the King.5

It is not merely an incidental detail that ‘all the people’ would have included high-ranking Persian women, who would participate openly along with the men in such royal feasting. This was one of the sharpest signifiers of Persian ‘otherness’ to disapproving Greek eyes. A king would also take the women of his closest family with him on campaign, another stigma of Persian strangeness for a Greek.

Herodotus, on what authority we cannot say, feels confident enough to record in detail what each of his twenty satrapies was bound to contribute annually. For instance, the Greeks united in his Satrapy number 1 paid only in monetary form, silver or silver equivalent, whereas the Egyptians of Satrapy 6 had included in their assessment a sum of money raised from the sale of fish caught in Lake Moeris; and as for the Indians of Satrapy 20, as noted above, they were ‘the most populous nation in the whole known world and [therefore] paid the largest single sum, 360 talents’ weight of gold-dust’. Moreover, he comes up with a grand total annual assessment, in silver equivalent reckoned on the weight standard of the island of Euboea (heavier than the more universal Athenian standard), of over 14,500 talents.*

Herodotus, perhaps surprisingly, does not include here the products of what we might call the ‘white slave’ trade – young girls to stock the harems of the central and regional capitals, for both sexual and reproductive purposes, and castrated boys, including Greeks, to serve eventually as eunuch guards of those same harems and more immediately as sex-objects.† Herodotus moreover was unaware of, or chose not to record, how a province’s military obligations might be met indirectly by a complicated system of ‘franchising’. Rich Babylonians, for example, instead of serving in person, usually as cavalrymen, might pay a sum of money to a third party, a middleman, who would purchase the services of a substitute and pocket the difference between what the rich opt-out paid him and what the substitute cost. The records of the Murashu (‘wildcat’) family finance house of Nippur have survived to throw a great deal of light on this franchising system, which may also help to explain why some at least of the Persians’ cavalry recruits fought with less élan, though not necessarily any less skill, than some of the Great King’s wealthiest subjects.

With all the aristocratic scorn he can muster, Herodotus adds confidently6 that ‘the Persians have a saying’ to the effect that, whereas Cyrus was a ‘father’ to them and Cambyses a ‘tyrant’, Darius was merely a ‘tradesman’ or ‘retail trader’ (emporos). Actually, that was a thoroughly Greek rather than Persian mode of classification, and it is an irony that Herodotus fails to bring out just how desperately foreign and un-Greek the whole Persian system of centralized bureaucracy was. It has been well said that everyone in the Persian empire, from highest to lowest, was on a ration scale. This emerges most strongly from two sets of texts from Persepolis, known respectively as the Fortification Tablets (a cache of more than thirty thousand, excavated in 1933/4, comprising an economic archive of Darius’s reign written almost entirely in Elamite, the local language of the area of which Susa was the capital – though there was at least one ethnic Greek scribe or secretary at work there too) and the Treasury Texts (a mere 750 or so, also written in Elamite, dating between 492 and 458).

Pharnaces, for example, was specially favoured to receive as his daily – daily! – ration 90 quarts of wine, 180 quarts of flour and 2 sheep. Gobryas, Darius’s helper and father of Xerxes’s general Mardonius, got even more (about 11 per cent more). The scope for dispensing power and patronage that such an overblown food allowance implies need hardly be laboured. Travel rations were another kind of central dole, issued to groups and individuals journeying on official business across the Empire. Travellers thus provisioned are registered as coming from southern Elam, from Persis and even from India. Destinations mentioned include Arabia, Bactria, Babylon, Egypt, Kerman and Sardis.

The latter was the terminus of the so-called Royal Road from Susa that so impressed Herodotus. Whereas a sizeable army would typically require three months to travel that distance (almost 2,600 kilometres), a single messenger using a relay of horses along the Royal Road could cover it in little over a week. Herodotus goes into inordinate detail in his description of the Road’s course and length,7 using the technical Persian term parasang – though he seems to have understood this wrongly as a unit of distance when it was a unit of time. Elsewhere8 he likens the relay of horses at the Royal Road’s reportedly 111 stations, or posthouses, to the relay of torches carried by runners in races held at Greek religious festivals in honour of the Olympian craftsman-god Hephaestus. The highway started from Susa, went through one (not certain which) of the passes of the Zagros Mountains, thence to the Tigris and on to the upper Euphrates, then on through Cappadocia to Sardis – and from Sardis on to the Aegean coast at Greek Ephesus in Ionia. This was one of the reasons for the heavy Persian influence on Ephesus, extending even to its famous civic cult of Artemis, who was assimilated somewhat to Persian Anahita.

Besides the required tax and tribute contributions there were other forms of economic exploitation available – for example, the confiscation of Greek lands by the satrap or even by the Great King himself, and their redistribution to favoured Persian or even Greek grandees. But, as already noted, the imperial yoke was not apparently felt to be an especially heavy one in economic terms, and so long as the contributions came in regularly and on time, subjects were not massively oppressed.

Religion featured prominently in imperial Persian propaganda. Twice in the documents quoted above Darius refers to Ahura Mazda, ‘Lord Wisdom’. He was the great god of light of the Irano-Bactrian religion founded or codified by the prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra), who was born in Bactra (Balkh) probably sometime between the tenth and sixth centuries BCE. An even more explicit commitment to Ahura Mazda was made by Darius in the famous trilingual rock-cut inscription at Bisitun not far from Ecbatana.* The languages were Elamite, Babylonian and Old Persian. The latter was an official, chancellery language rather than an imperial lingua franca, and all the more imposing for that, though Darius seems to have been the only Achaemenid king who had proper texts composed in it, and took pleasure in doing so.

The Bisitun texts were inscribed some 66 metres above ground level in the living rock of a mountain on the slope of which have been found the possible remains of a Median fortress. The name ‘Bisitun’ is derived from an Old Persian word meaning ‘place of the gods’, and of those gods first and indeed only place was given to Ahura Mazda, whose image – a winged symbol – accompanied and indeed dominated the inscription:

Darius the king says: ‘… By the favour of Ahura Mazda I am king. Ahura Mazda bestowed kingship upon me … They [specified countries] were my subjects; they brought tribute to me … By the favour of Ahura Mazda these countries obeyed my law … Ahura Mazda bestowed this kingdom upon me. Ahura Mazda brought me aid until I had held together this kingdom. By the favour of Ahura Mazda I hold this kingship.’

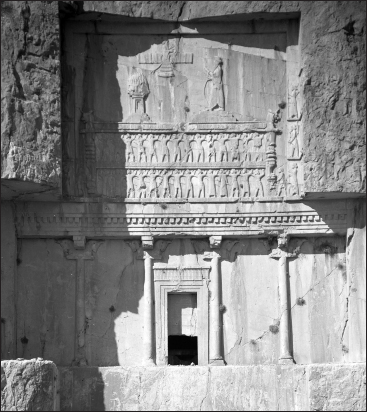

The insistent repetition is very striking; it parallels the deliberate repetitiveness of the figural decoration of the royal palaces. Striking too is the fact that, unlike the Pharaohs of Egypt, the Persian Great Kings were not themselves considered divine. They were instead the vicars on earth of Ahura Mazda, of whom in another inscription Darius fulsomely says: ‘Ahura Mazda is a great god, who created this earth, who created the sky, who created humankind, who created happiness for humankind’ – and then segues seamlessly into ‘who made Darius king, one king of many, one lord of many.’ Or, to quote a slightly variant version from an inscription of Darius incised on the façade of his tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam near Persepolis: ‘Ahura Mazda is a great god, who created this excellent work which is seen, who created happiness for humankind, who bestowed wisdom and courage upon Darius.’

The facade of Xerxes’s tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam displays the king in an attitude of homage to the same winged-disc symbol of Ahura Mazda as his father Darius had employed at Bisitun.

As the anointed of Ahura Mazda, Persian Great Kings were owed maximum respect, symbolized by the performance of a ritual of public greeting that the Greeks called proskunêsis. This consisted, depending on the status of the subject performing it, either of a full prostration or of a deep bow from the waist coupled with a blown kiss. This sort of gestural body language, de bas en haut, was entirely appropriate to the Persians’ pyramidal sort of society and political system. Monarchy was the apex of the Empire’s governing order, without any possibility of question. The Great King, King of Kings, had his duties assigned to him from heaven above, mainly to protect land and people from natural and manmade incursions. But this monarchical political system did not – quite – reflect an imposed imperial monotheism. For there were other gods and goddesses in the Persian pantheon, Anahita and Mithras for example, and despite all Darius’s and other Great Kings’ efforts to make it seem otherwise, the Empire as a whole remained polytheistic in outlook and behaviour.*

The erection of the Bisitun inscription towards the beginning of Darius’s reign was obviously propagandistic. It was designed to demonstrate – and illustrate – that central order and control had been reimposed following a very widespread bout of disaffection and indeed outright revolt following the death, in murky circumstances, of Cambyses son of Cyrus in 522. There is no hint that this disaffection and revolt had been caused by religious opposition. But unrest leading to open revolt at the close of Darius’s reign in the provinces of Babylonia and Egypt does indeed suggest that Ahura Mazdism came at a cost in regions where the political order was shaped or dictated in accordance with the perceived wishes of other all-powerful deities. In both those key provinces the senior priesthoods (of, respectively, Bel-Marduk and Amun) were apparently the most active forces behind the rebellions, and it was they whom Xerxes chose to punish, perhaps rather heavy-handedly, as his first acts as Great King.

In the case of Persian official dealings with the Greeks, a rather telling piece of epigraphic evidence goes in precisely the opposite direction. The text in question was cut into a marble block in the second century CE in the Greek city of Magnesia (on the River Meander in Ionia), probably at the instigation of priestly authorities keen to establish publicly the sacredness of the land at issue. But there is every reason to think that the document is an authentic copy of an imperial order of Darius originally delivered to Gadatas, satrap of Lydia and Ionia, in about 500 BCE:

The King of kings, Darius, son of Hystaspes, speaks to Gadatas, his slave, thus: ‘I find that you are not completely obedient to my orders. Because you are cultivating my land, transplanting fruit trees from the Province Beyond-the-Euphrates [Syria-Palestine] to the western Asiatic regions, I praise your purpose … But because my religious dispositions are nullified by you, I shall give you proof of a wronged [King’s] anger, unless you change your ways. For the gardeners sacred to Apollo have been made to pay tribute to you; and land that is not sacred they have dug up at your command. You are ignorant of my ancestors’ attitude to the god, who told the Persians all of the truth and …9*

Darius’s tactful reference to his ancestors would have been music to a Greek subject’s ears, since to the Greeks tradition, the honouring of their gods ‘in accordance with the things of the fathers’ (kata ta patria), was of the essence of their religious custom (nomos) and belief. Greeks were perhaps on the whole not quite as devoted gardeners as the Persian Great Kings; it is to the Persians that we owe the Edenic term ‘paradise’ (from pari ‘around’ and dieza ‘wall’), meaning originally a cultivated hunting park. Yet they too appreciated the distinction between the sacred and the not so sacred, between precincts (temenê) ‘cut off’ as special places for their gods and land that had not been so sanctified and sacralized. And they would have found Darius’s toleration of a foreign, Greek cult entirely congenial and culturally familiar too.

But Darius’s use of the phrase ‘all of the truth’ in the truncated last sentence was peculiarly Persian. Herodotus insists that the whole of a Persian’s education between the ages of five and twenty was devoted to the instilling of just three virtues or skills: riding a horse, shooting the bow, and telling the truth. Telling lies was the worst possible violation of the Persians’ honour code – ahead of, in second place, owing a debt. In the Bisitun trilingual inscription Darius presents himself as the very embodiment of the Truth, engaged in battling against the usurper and the rebels who incarnate the Lie. Indeed, all Persian royal inscriptions try to convey eternal verities about the Great King. Their overriding aim was not to record individual political events (though they do sometimes do that too) but to emphasize that the King’s rule is divinely ordained and that the peace of the Empire is to be secured only through following the Truth, specifically by adhering to the moral precepts of Ahura Mazda.

Another in the early fifth century. Athenian series of Persian vase scenes, this cup of c. 480 by the so-called Triptolemos Painter shows a defeated Persian on the (sinister) left, carrying both sword and bowcase, and a victorious Greek hoplite on the (might is) right.

Further confirmation of the official royal conflation of Ahura Mazda with the Truth comes from a famous document of Darius’s son, Xerxes, his so-called ‘Daiva-Inscription’, a daiva being Old Persian for a demon or devil:

Among these countries [the thirty or so listed immediately above in the text, over whom Xerxes’s data (law) was asserted to prevail] there was a place where previously demons had been worshipped. Afterwards … there I worshipped Ahura Mazda in accordance with Truth reverently …10

Just as specifically Persian, likewise, is Darius’s use of a term that can be translated as ‘slave’ in Greek, even when addressing so high-ranking a Persian as a satrap, who might well have been related to him by birth or by marriage. That hateful parlance would, however, have struck a deeply false note to a Greek audience and very possibly gives a clue to what was at least part of the reason for the Ionian and other Greeks revolting against him in 499.

This revolt, like the revolts of 521–519, in which Greeks were not involved, was forcibly suppressed. But Darius did not aim merely to hang on to the empire he had inherited. He burned also, like Cambyses, to expand it. In 513, as noted, he moved his forces across the Bosporus strait from Asia into Europe and established a new satrapy in Thrace or, as it was officially known, Beyond-the-[Black]-Sea. A basis had been laid for further conquest in the southern Balkan peninsula – that is, conquest of the Greeks of Macedonia and points south. But, whether that was how it was seen by Darius at the time is another question, unanswerable on current evidence.