FOUR

SPARTA 485:

A UNIQUE CULTURE

AND SOCIETY

Sparta, world-famous home of a narrow military aristocracy, with its haughty pride of race, its relentless discipline and its ruthless oppression of its subjects …

M. N. Tod, ‘Retrospect’, 1944

THE SPARTANS, notwithstanding their extraordinary patriotic pride and military prowess, were by no means entirely friends to freedom. As we saw earlier, at home in Laconia and Messenia they exercised for several centuries a ruthless domination over native Greek populations many times the size of their own, to whom they gave the derogatory collective label ‘Helots’, or ‘captives’. Professionals in a world of amateurs, the Spartans alone of Greek cities maintained a standing army. But they were not militaristic in the sense that they enjoyed war for its own sake. That unique army was invented and maintained, first and often foremost, to dominate and suppress the Helots. In fact, their whole society was organized as a kind of standing army. It was kept ever on the alert against the enemy within, as well as against any Greek or non-Greek enemies from without. It was no accident that the Spartans’ Messenian Helot problem should have figured prominently in Herodotus’s account of a significant visitor to Sparta in 500.

The visitor was Aristagoras from Miletus. Not many foreigners ever set foot in Sparta, let alone foreigners from the non-Dorian Greek world of Ionia far across the Aegean Sea. But Aristagoras had a specially compelling mission: to secure Spartan military support for his proposed revolt against Persia – the Ionian Revolt, as it is known (see Chapter Three). Aristagoras was in the parlance of Herodotus’s day a ‘tyrant’, an unelected, non-responsible sole ruler. He owed his position to the patronage of his predecessor Histiaeus and to his control of superior military force backed by the support of the Persian satrap in nearby Sardis. He was not perhaps an unmitigated despot any more than, for example, Peisistratus tyrant of Athens (died 527) had been. But his very position was enough to cause suspicion, especially as he had been ruling Miletus in effect as a pro-Persian quisling, or puppet.

As Herodotus tells the story, the Spartan citizen body as such was not consulted at all on whether they wished to support Aristagoras against Persia. This may just be an accidental omission, but it may equally well reflect the fact that Sparta’s political arrangements were fundamentally oligarchic, disguised only by a veneer of popular consultation. Sparta in 500 was dominated by a powerful king, Cleomenes I, who controlled the tiny and elite Spartan Gerousia,* or Senate (comprising its twenty-eight elected members, together with the other king ex officio, making thirty in all). This meant he was in a position to dictate the policy of Sparta, regardless of the views of the citizenry as a whole. But Herodotus gilded the lily a little by making out that the only Spartan with any decisive influence over the King was a young girl of about eight – his only child, Gorgo (future wife of Cleomenes’s half-brother Leonidas). Aristagoras was allegedly making some headway in attracting Cleomenes’s support, by pandering to the known Spartan susceptibility to bribes, when Gorgo sharply reminded her father of where his moral and regal duty lay.

Herodotus in his usual way does also reveal what really told against Aristagoras. In order for the Spartans to lay their hands on the wealth stored at Susa, they would have to undertake a march of some three months inland into Asia, far away from the Aegean coast. But the Spartans were essentially landlubbers. In 525, as we saw in Chapter One, they had essayed an aggressive foray as far across the Aegean as the island of Samos, in an attempt to unseat the tyrant Polycrates. But that unsuccessful attempt offered no precedent for the sort of amphibious expedition that Aristagoras was advocating. So the Milesian left Sparta empty-handed. In newly democratic Athens, however, he had far greater success, which gave Herodotus the opportunity to contrast favourably the refusal of the one Spartan, Cleomenes, with the agreement of thirty thousand gullible Athenians.*

Cleomenes’s supremacy in Sparta was exercised at no small political cost. He had acquired the throne hereditarily reserved to the Agiad royal family in about 520 in controversial circumstances, since he had been born to his father Anaxandridas’s second – and bigamous – wife. Dorieus was the oldest son of Anaxandridas’s first, wholly legitimate wife, but he had been born after Cleomenes and his claim to the succession was rebuffed. He therefore took himself off in a giant huff and embarked upon a series of adventures in north Africa and Sicily, where he died. In about 515 the other royal house, that of the Eurypontids, experienced a much smoother succession, which brought Demaratus to the throne. But Demaratus too had a chequered past, and there was a question-mark over his legitimacy that Cleomenes was eventually to turn into a full stop. Indeed, he and Cleomenes probably never got on very well with each other; that, according to Herodotus, was a normal feature of relations between the two royal houses. In 506 they fell out spectacularly – publicly, and with fatal consequences, at first for Sparta’s foreign policy and eventually for Demaratus himself.

This exceptionally handsome bronze figurine of a hoplite fighter decked out in his finest parade armour was made by a Perioecic craftsman and dedicated in a Perioecic sanctuary of Apollo in south west Messenia towards the end of the sixth century. As if to show that Perioeci could be the equals of their Spartan overlords, our hero is accompanied by his favourite hunting dog, of whom only a trace is preserved.

Sparta by the middle of the sixth century was already considered the strongest military power in mainland Greece; hence Croesus of Lydia’s concluding an alliance with Sparta against the incoming tide of Persian might (though actually the alliance bore no fruit). Specifically, Sparta had the strongest land army, the core of which was its citizen hoplites. Unlike in all other Greek cities, every Spartan full adult citizen was also, by definition, a member of Sparta’s hoplite phalanx. Again unusually or uniquely, hoplite arms and defensive armour were provided centrally to Spartan warriors. This was from an arsenal stocked and maintained by the labour of sub-Spartans called Perioeci or ‘dwellers around’. Since the Spartans themselves were forbidden by law to practise any other trade or craft than warfare, their weapons and armour were manufactured for them by the free but politically unenfranchised inhabitants of some eighty small towns and villages concentrated mainly in upland and coastal Laconia but with a scattering around the coast of Messenia too. Some Perioeci were wealthy enough to be able to equip themselves to fight as hoplites, and Sparta came to draw ever more heavily on these support hoplites in the course of its history.*

Freed by compulsory Helot labour from the necessity to earn their bread, Spartan citizen hoplites were compelled to drill, drill, drill and in other ways too to train incessantly in preparation for an immediate call to arms. The Helot underclass were always threatening to rise up in significant numbers against their masters. So, at the beginning of each new civil year Sparta’s chief elected officials, the board of five ephors (overseers, supervisors), formally declared war on them. If any Helots did choose to rebel, they might then be killed with impunity, without the killer’s incurring the taint of religious pollution that otherwise inevitably accompanied the shedding of human blood.

The ephors too had general oversight of the Spartans’ unique educational system, the agôgê (upbringing). This had been devised chiefly for the boys, in order to turn them into suitable officer material as adults. Successful graduation from the agôgê was a requirement for a Spartan male to permit him to join the group of full citizens known as homoioi, or peers (literally ‘similars’). But it was also applied – separately but almost equally – to the girls. From the age of seven a Spartan boy was removed from his parental home and required to live in a public dormitory-cum-barracks that served as a schoolhouse too. He was kept on very short rations, so much so that he might find himself reduced to stealing even a not very appetising wild fox. This gave rise to the iconically Spartan tale of the boy who was interrupted shortly after he had caught a fox and interrogated by one of his educators. Under the rules of the agôgê stealing by the boys was permitted, and even encouraged (to develop the skills of stealth, surprise and resourcefulness that might well come in handy in adulthood on campaign). But being caught redhanded in the act of stealing was absolutely forbidden and severely punishable, so the boy in the tale stuffed the fox under his tunic (the one tunic he was allowed per annum). And rather than utter a cry that would betray his theft, he stoically kept silent as the fox gnawed away at his vitals until he dropped down dead in front of his inquisitor. Exaggeration aside, the message of the necessity of stoical obedience was unambiguous – and its pedagogic effectiveness ensured that it was repeated and preserved.

Another such cautionary tale concerns a rather older, teenage Spartan youth. He made the bad mistake of crying out in pain when taking part in the vigorous physical mauling that constituted a large part of the Spartan educational cycle – or endurance test – at that stage of his life. His cries were heard by the seniors in charge, and the street cred of the teenager instantly plummeted as a result. However, unlike the boy with the fox, it was not he who was liable to be formally reprimanded and punished – but instead his lover, a young Spartan citizen. The thinking was that the older, adult mentor had failed to inculcate properly Spartan values and behaviour into his adolescent beloved.

Such literally pederastic (‘boy-desiring’) pairing relationships between an unmarried young adult citizen warrior (aged, say, twenty to twenty-five) and a teenaged boy (aged between fourteen and eighteen) were not abnormal or unusual; actually, they were more or less obligatory for all in Sparta, as part of the agôgê. The Spartans even devised a special local vocabulary for them: the older partner was called the ‘inspirer’ and the younger one the ‘hearer’. Of course, these metaphors might well have been a cover for the relationship’s carnal and earthy aspects.* Sharing in a lopsided partnership of this nature had for the junior party the force of an initiatory ritual, an essential step along the gruelling road to his achieving full manhood. It is not unlikely, either, that it could have implications for political and other sorts of relationships at later stages of a Spartan’s life.†

The institutional practice of a state-run, comprehensive educational system for all boys was unique to Sparta. Likewise unique was the parallel cycle for Spartan girls, which also placed a premium on physical fitness, though its overall aims were of course different, since in Sparta as elsewhere in Greece women were deemed the non-military half of the citizen population. Whereas the boys were being groomed for adult warriorhood, the girls could not aspire to being initiated into the mystery of martial bravery and courage encapsulated in the term ‘manliness’ (andreia) that could also mean ‘courage’. Instead, the females were being officially prepared for the almost equal honour they were granted as wives and mothers, ideally the mothers of future warriors.

Sparta according to the poets was a city ‘of broad dancing-floors’, and this vigorous bronze figurine of a dancing (or running) Spartan female of the later sixth century was a wonderful advertisement for her city as she was exported as far afield as southern Albania (northern Epirus in antiquity).

The Spartans placed a premium on reproduction (teknopoiia, literally the ‘making of children’), mainly, one supposes, for fear of the vastly larger subordinate population of enslaved Helots by which they were surrounded. It was, then, in the eugenic belief that physically fit women would be more successful mothers of sons that all girls were given a training in athletics, including wrestling and throwing the javelin as well as running, besides a more typically Greek schooling in singing and dancing.* Though the girls, unlike their brothers, continued to live in the parental home with their mothers until marriage, what they were deliberately not brought up to perform were the standard domestic tasks of cooking, cleaning and clothes-making that fell to the lot of all other Greek girls and wives. Those were reserved for Helot women. Spartan mothers didn’t even play the major role in child-rearing, again because of the ready availability of Helot wetnurses and childminders. Instead, a huge amount of attention was paid to ensuring that the female half of the population internalized the state’s dominantly masculine values.

Hostile non-Spartan critics took pleasure in condemning the women for failing to abide by the strict and austerely community-minded ‘laws of Lycurgus’.* They were allegedly overfond of luxury and wealth. This included landed property, which, exceptionally in Greece, Spartan women could own in their own right. They were castigated too for their lack of self-discipline, and even for their cowardice in the face of the enemy. When Laconia was penetrated, for the first time ever, right up to the town of Sparta itself in 370/69, the Thebans and their allies laid the Spartans’ fields waste, including those owned by women, right under their noses. Aristotle claimed that the women did even more damage to Sparta than the enemy! On the other hand, a friendly observer such as Xenophon could praise the Spartan women, rather, for their remarkably stoical reaction to the loss of their nearest and dearest menfolk at the Battle of Leuctra in 371.†

Besides developing Greece’s most efficient hoplite army, the Spartans also finessed their relations with the outside Greek world through carefully constructed diplomatic means. Like the educational cycle, this was prompted not least by concern about their internal security against the Helots. Within the borders of the Spartan state (known officially as Lacedaemon) there were also the eighty or so cities and towns of the free but politically subordinate Perioeci, who were expected to form the first line of anti-Helot defence. But it was also felt desirable to throw a further ring of confidence around Sparta’s extensive home territory, which at some 8,000 square kilometres was twice the size of the next-biggest state in the Greek world, that of Syracuse in Sicily.

The Spartans’ first external alliance was possibly concluded in about 550 with the nearest polis to the north, Tegea in Arcadia. But inside a generation their alliance system within the Peloponnese had been extended as far as the Isthmus of Corinth, and by the end of the sixth century or early in the fifth it had gone beyond the Peloponnese into central Greece, embracing Megara and the offshore island of Aegina. Allies swore one-sided oaths of subordinate loyalty to Sparta, guaranteeing to provide military support on demand in return for Sparta’s preserving the allies’ generally oligarchic regimes – a service that became more and more important following Athens’s conversion to democracy in 508.

The one Peloponnesian state that conspicuously refused to join Sparta’s alliance, as we noted earlier, was Argos, which challenged Sparta militarily in the field in about 545 but was very seriously defeated. The pattern was to be repeated quite regularly thereafter (494, 469, 418 …). In 525 Sparta felt confident enough even to throw its weight about in the eastern Aegean, with the crucial naval assistance of its ally Corinth. Again in 512 or so, in a bid to unseat the ruling ‘tyrant’ dynasty of the sons of Peisistratus, Sparta sent a naval rather than a land expedition against Athens. And this raises the general question of Sparta’s attitude to foreign tyrants, or autocrats. Sparta came to acquire the reputation of opposing tyrants on principle, since it did as a matter of fact depose a good few of them. But in all cases sound pragmatic reasons for the depositions can be advanced with equal plausibility, and there were at least two occasions when Sparta so far forgot its supposed anti-tyrannical principles that it attempted actually to impose or reimpose tyrants. Both these occasions fell within an extraordinary and history-transforming period of just half a dozen years, from 510 to 504, and both in relation to Athens.

Herodotus, who placed great emphasis on the Spartans’ extreme religiosity, believed that they had been persuaded to turn against the Athenians’ longstanding tyrant dynasty in 510 by a constant stream of Delphic oracles. At all events, the regime of Hippias and his brother was abruptly terminated by Cleomenes’s intervention, and Hippias made good his escape not merely into exile but into the arms of Persia. As a client now of Great King Darius, he nursed into extreme old age his dream of return and restoration. From a Greek perspective the nexus between Persia and mainland Greek politics had been decisively forged, confirming the link between Persia and Greek tyranny that was already institutionalized on the Asiatic side of the Aegean.

Two years later, in 508, Cleomenes was back in Athens, again with an army, and this time occupying the Acropolis for some days. But there was no chance here to claim that the intervention was in the name of securing freedom for the Athenians from oppression or tyranny, because Cleomenes was actually intervening against the clearly expressed wishes of the majority of Athenian citizens. They had declared that they favoured the imaginative and pioneering ‘democratic’ reforms proposed by Cleisthenes, a longstanding opponent of the old tyrant regime. Cleomenes, in the sharpest contrast, favoured a reactionary solution, the installation of Cleisthenes’s opponent Isagoras as a pro-Spartan quisling tyrant. So much for Sparta’s supposed opposition to tyranny on principle!

Cleomenes to his shame and embarrassment found himself blockaded on the Acropolis and forced to withdraw ignominiously to Sparta. But he retained sufficient clout to effect the temporary exile of Cleisthenes, for a second time, with a considerable number of his relations and closest supporters. That success proved to be transient. Cleisthenes soon returned, his reforms began to take root and to flourish – not least, as events were soon to prove, in the military department. So in 506 Cleomenes decided to try again to assert his will upon a recalcitrant Athens. This time he had, he thought, prepared the ground more thoroughly. The army he led was not just of Spartans, but of the Spartans and their considerable number of Peloponnesian allied states. Moreover, he had, he thought, arranged to co-ordinate his invasion from the Peloponnese via the Isthmus of Corinth with attacks on Athens from Boeotia (led by the Thebans) and Euboea (the city of Chalcis). But there were two flaws in the enterprise. The first was that, though the allies were clear at the start that the objective of the expedition was to exert Spartan power over Athens, it became clear to them only later that Cleomenes intended a repeat of his 508 ploy, the installation of Isagoras as tyrant. It seemed to some of the more important of the allies, especially Corinth, that Cleomenes was thereby overstepping his stated remit, and Corinth’s memories of its own tyrant dynasty were still rather too fresh.

The second, and more damaging, flaw was that Cleomenes had failed to carry his co-king Demaratus with him, ideologically and morally; physically, Demaratus did indeed accompany the army as it headed for the Isthmus, presumably because it was then still quite normal for both kings to lead out such a major force. At a crucial moment, though, and in concert with the Corinthian allies, Demaratus simply withdrew and returned to Sparta, so that the Spartan part of the concerted pincer movement on Athens was left in complete disarray, a total shambles. The Boeotians and Chalcidians nevertheless went ahead with their attack from the north and east, only to be soundly defeated by the new-style democratic army of Athens, in high spirits as they fought not just to protect their sovereign independence but also to preserve their revolutionary new political regime. Even so, in about 504 the Spartans tried yet again. And this time, such was their desperation that the tyrant they proposed to impose on Athens was none other than the old one, old in both senses: Peisistratus’s son Hippias, the ‘medizing’ refugee at the Persian court.

Herodotus does not actually name Cleomenes in connection with this final attempt, and it is possible that he prudently hung back, despite approving the project. What scuppered this last initiative was not Demaratus – or not Demaratus alone – but a collective decision taken by majority vote in Sparta of representatives of all Sparta’s inner circle of allies. In other words, no longer could a Spartan king simply dictate to the allies, but the allies had acquired a collective voice, and a collective right to be heard. Modern scholars mark this moment as the birth of what they call the Peloponnesian League. Sparta retained the initiative vis-à-vis its allies; that is, the allies could not commit Sparta to a foreign policy of which it disapproved, and it was for Sparta to make up its own mind first in closed deliberation before summoning the allies to a public conclave to gain their approval. But the vital clause inscribed in all treaties of alliance, to the effect that an ally must ‘follow the Spartans whithersoever they may lead them’, had now been crucially modified to give the allies, collectively, a right of veto by majority vote.*

This was the Sparta, headed by King Cleomenes, that Aristagoras visited in the year 500, a somewhat chastened Sparta but still the preeminent military power on the Greek mainland. Untempted by Asiatic adventures, the Spartans were to be much preoccupied with Peloponnesian matters nearer to home in the 490s. Aristagoras had, according to Herodotus, advised the Spartans to suspend their petty local wars over pitifully poor scraps of land ‘with your rivals the Messenians, the Arcadians and Argives’.1 There is no other certain evidence that Sparta was hotly engaged in dispute with any of the Arcadian cities at this time, though the issue of a coinage bearing the legend Arkadikon (the Arcadian federation) has sometimes been dated as early as 490 or thereabouts. This could have betokened the formation of a quasi-nationalist Arcadian federation, which would inevitably have been considered inimical to Sparta’s geopolitical interests. Sparta’s general policy was always to try to divide the Arcadians among themselves, the more easily to rule them, in particular keeping the polis of Tegea firmly separate from and opposed to Mantinea in eastern Arcadia. Nor is there other much sounder evidence that the Messenians, that is the Messenian Helots, were then posing any greater threat to Sparta than they constantly posed, though Plato does make one of the characters in his mammoth Laws dialogue allege that at the time of the Battle of Marathon (490) the Spartans had to face a Helot uprising.

There is very good evidence indeed, on the other hand, that in the 490s the Spartans, under Cleomenes, were clashing once again with the auld enemy Argos, and once again dishing out a slashing defeat. Indeed, it removed Argos from the board as a serious player for an entire generation. The centrepiece was a battle, probably in 494, fought at Sepeia in the Argolid region, so the Spartans were clearly the aggressors. Herodotus’s interest is not in the battle’s military details but in Cleomenes’s actions after the battle, which he uses as yet another stick with which to beat his villain of the piece. Several thousands of Argive survivors, he reports, had taken refuge in a sacred grove as suppliants. Cleomenes unscrupulously ordered the Helots in his entourage – so that he would not himself be directly tainted with the religious pollution – to set fire to the grove, and thereby killed most of the suppliants. But so far as the Spartans themselves were concerned, this was not his only alleged offence. When he returned to Sparta, after a campaign that had after all been a huge success in pragmatic terms, he was put on trial for his life: for failing to take the city of Argos itself.

Such trials of Spartan kings were held in camera before the permanent Gerousia and the board of five ephors of the year; there were no popular lawcourts in Sparta ever, unlike the system that was developed most conspicuously in democratic Athens, for example. So most likely the chief accuser was none other than Cleomenes’s fellow king Demaratus, his rival and enemy. The ephors, it seems, had to make a preliminary judgement – anakrisis – as to whether there was a charge to be met, and Demaratus perhaps had a majority of the ephors on his side. Nevertheless Cleomenes managed to get himself off, and he did so in a thoroughly cunning, because thoroughly Spartan, way. He claimed that as he had gone to offer sacrifice at the Argive Heraion, the shrine of Argos’s patron goddess Hera, a portent had declared itself. A flame had shot forth from the breast of the goddess’s magnificent chryselephantine cult statue. From this sign he said he knew with absolute certainty that it was not fated that he should capture the citadel of Argos, for, had that been so, the flame would have shot out of the statue’s head, not from its breast. The Spartans, says Herodotus, found this ‘a credible and reasonable defence’.2

In those few words Herodotus has contrived to say a huge amount about Sparta. Apart from its educational and military systems, Sparta’s third most palpably distinctive cultural feature was its religious system. Elsewhere, and twice over, Herodotus comments on the exceptional piety, or religiosity, of the Spartans: ‘they esteemed the things of the gods as more authoritative than the things of men’.3 Well, actually all conventional Greeks did that much, so what Herodotus, himself a man of powerful religious motivation and conventionally Greek piety, surely means to imply is that the Spartans judged their duty to the gods to be much more absolute and binding. In a way, they applied to their attitude to the gods their outlook on life in general – one of order, hierarchy and unquestioning obedience. The gods stood, as it were, at the very apex of a tall pyramid of authoritative command. It was no coincidence that in Sparta every god and goddess was represented wearing arms and armour. The city’s patron goddess was Athena, who despite her gender was regularly represented throughout Greece as wearing a helmet and breastplate and carrying a spear. But it was in Sparta, uniquely, that even the manifestly unwarlike Aphrodite (connoisseurs of Homer’s Iliad would smile) was given an incongruously martial aspect.

This almost blind devotion to the gods explains why the Spartans went to inordinate lengths to find out in advance if they possibly could – through examining the entrails of sacrificed animals or consulting oracles, for instance – what the divine will was. We even hear of Spartan commanders, though faced with the absolute need to take an urgent decision in the heat of battle, sacrificing and sacrificing again and again until they received a divinatory answer they found acceptable and actionable. For this the Spartans were dubbed ‘expert craftsmen in military matters’ by Xenophon, a conscious metaphor since they were forbidden to be skilled craftsmen in the literal sense. One highly pertinent aspect of the Spartans’ quite exceptional religiosity – exceptional not only in ancient Greek terms – was their attitude to death.

Plutarch in his ‘biography’ of Lycurgus says that the lawgiver was very concerned to rid Spartans of any unnecessary or debilitating fear of death and dying. To that end, he permitted the corpses of all Spartans, adults no less than infants, to be buried among the habitations of the living, within the regular settlement area – and not, as was the norm elsewhere in the entire Greek world from at latest about 700 BCE, carefully segregated in separately demarcated cemeteries away from the living spaces. The Spartans, in other words, did not share the normal Greek view that burial automatically brought pollution (miasma). They believed that the cremated or inhumed bodies of their ancestors were a source of communal solidarity and strength rather than weakness, and something to be embraced and literally lived with rather than abhorred and shunned and put out of sight as well as out of mind.

On the other hand, the Spartans did reserve two spaces for burials well outside the habitation area of the town of Sparta; though ‘burials’ is perhaps misleading. One was the Caeadas, a gorge that has been identified at the modern village of Trypi (‘Hole’) some way west of Sparta near the entrance to the Langhada pass leading through the Taygetus mountain range into Messenia. Into this ravine were tossed the bodies of criminals condemned for capital crimes. The other space is much more interesting from the viewpoint of Spartan attitudes to life and death. The Spartans, as noted, were very preoccupied with the reproduction of their citizen population, but sheer numbers alone were not enough. Quality too mattered. Thus newborn infants (of both sexes, perhaps, but the males were at this stage much the more important) were submitted to a ritual inspection and test conducted by ‘the elders of the tribesmen’, as Plutarch puts it. They were dunked in a bath of presumably undiluted wine, to see how they reacted. If they failed the test, the consequences were fatal. They were taken to a place called cryptically ‘the deposits’ (apothetai) and hurled to their certain deaths into a ravine.* So too were those infants unluckily born with some serious and already obvious physical deformity or disability.

‘Exposure’ of newborns was by no means unique to ancient Sparta. It was positively recommended, too, in the utopian philosophical prescriptions of both Plato and Aristotle. But in other Greek cities the procedure was a good deal more gentle and differently configured. Parents – and not the state – had complete control over the process, and exposure might more often be resorted to for economic than for eugenic or state-dictated motives. Nor was there necessarily any expectation, let alone desire, that exposure would automatically mean death. At Athens, for example, there was a recognized term ((en)khutrizein) for the practice of placing exposed infants in a large earthenware pot, in the hope that some other family, childless for physiological or other reasons but materially able and psychologically willing, might pick them up and rear them.

So not only were Spartans brought up in the close company of death and burial but they were taught to be prepared for the loss of an infant deemed to be a public encumbrance, a burden on the state. Consistently with that view, the Spartans did not feel the need to make a song and dance of the burial and mourning process; the giant exception that was the state funeral of a Spartan king proved that rule spectacularly.* So a dead Spartan man, woman or child was not buried in a lavish, let alone a visually prominent or monumental tomb, but in a simple earth-cut pit accompanied by a minimum of grave-goods; Plutarch says the regulations for an adult male burial allowed just his famous scarlet military cloak, with the corpse laid on a simple bed of olive leaves. (This, incidentally, could explain why so few Spartan graves of the historical period have ever been unearthed.)

A dead Spartan was not allowed even the relatively minor luxury of a headstone with an identifying name inscribed on it – with two exceptions. First, a soldier who had been killed in battle was allowed to have his name inscribed on a tombstone followed by just the two stark words ‘in war’ – a truly laconic message. Laconic (Spartan) speech was brief, curt and clipped, but proportionately every syllable was supposed to be made to tell. Such posthumous commemoration was the logical next step after the Spartans’ glorification and exaltation of the warrior’s ‘beautiful death’ in battle. This attitude goes back at least to the middle of the seventh century, as it is found already in the poetry of Tyrtaeus: ‘endure while looking at bloody death / and reach out for the enemy while standing near’.4 Tyrtaeus served as the Spartans’ national war-poet, and his martial poems were preserved down the ages, being learned compulsorily by heart by boys during their education and recited by them regularly as adults when on campaign. The point about ‘standing near’ is that this is hoplite poetry: Tyrtaeus envisages hand-to-hand phalanx combat of the bloodiest kind.

The second exception and exemption concerned either priestesses or – but this alternative requires a serious modification of Plutarch’s text as transmitted – women who had died in childbirth. Both alternatives can be given perfectly reasonable explanations within the general context of known Spartan communal values. The exaltation in death of priestesses would be entirely consistent with the Spartans’ privileging of religion – the relationship of men to the gods – ahead of secular matters involving the relationship of men to men. The singling-out of women who died in childbed would corroborate the society’s preoccupation with reproduction, as well as put the contribution of a mother (especially a mother of potential warrior sons) on a par with the social contribution of an adult male fighter: the former gave a new life for Sparta, the latter gave up his life for Sparta.

Xenophon’s record of the aftermath of the Battle of Leuctra in 371 brings out just how odd were the official Spartan attitudes to the death of a relative. At Leuctra in Boeotia Sparta suffered its first major defeat in a pitched infantry battle, at the hands of the Thebans and their allies. More than half of the Spartans fighting had been killed, and their deaths had reduced the total adult male citizen population of the polis to under one thousand – compared to the then 25–30,000 citizens of Athens, for instance. This was a massive catastrophe, both collectively and individually, both publicly and – in so far as this distinction could usefully be drawn in Sparta – privately. (Since a lot of effort was put into the inculcation of official attitudes through education and habituation, unofficial, individual and private attitudes were probably quite similar.) Yet when the news was brought home, and individual families were told which men had died, the relatives of the slain went about with cheerful, almost delighted expressions, whereas the relatives of the survivors, so far from being thrilled or relieved, were humiliated by what they regarded as a double insult – not only had the state’s army been defeated, but their relatives had lived to tell the despicable tale; so they cowered away from public view in a state of shock and self-hatred.*

In short, the Spartans – uniquely in all Greece – took the view that death in itself was nothing to be feared but rather something to be literally lived with and daily stared in the face. How you died mattered no more – and no less – here than it did elsewhere in Greece; only in Sparta there was always a powerful and often an overwhelming emphasis on the public dimension of any death rather than on the private and purely familial one. The searing relevance of this attitude and behaviour to the Thermopylae campaign becomes almost painfully apparent.

With Argos out of the way and himself cleared of the capital charge, Cleomenes was free to direct Sparta’s attention for the first time across the Aegean and towards the rising Persian menace. This is the sole occasion on which Herodotus bestows on him unqualified praise. In 491 the ruling aristocracy of the strategically key island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf (‘the stye in the eye of the Peiraeus’, as Pericles was to call it) decided to medize: they gave earth and water to Darius’s envoys as tokens of their willingness to submit to Persian imperial hegemony. Cleomenes at once marched and sailed to Aegina, where he met fierce resistance led by an aristocrat called Crius, or ‘Ram’. Crius accused Cleomenes of having been bribed (yet another example of this standard accusation against Spartans) by the Aeginetans’ enemies, the Athenians. For, he said, if Cleomenes’s intervention in the affairs of an allied but independent state had been formally authorized by the Spartan state, both kings would have come, not just Cleomenes alone.

Crius here was certainly playing on and hoping to exploit the known enmity between Cleomenes and Demaratus, but he might also have been appealing to a possible constitutional requirement that both kings be in agreement on such matters of external intervention. However that may be, Cleomenes was not to be brooked or balked. After uttering a typically laconic remark – ‘You had better get your horns sheathed in metal, Ram’ – he returned to Sparta, engineered the deposition of Demaratus, and replaced him with the more amenable Leotychidas.*

As in the Argos episode of 494, Cleomenes found himself compelled to resort to religion against Demaratus, but here he overreached himself. Sparta had long had a special relationship with the uniquely authoritative oracle of Apollo at Delphi, and maintained a hotline to the priesthood there by way of four permanently appointed ambassadors to the shrine, known as Pythioi. These Pythioi were crown appointments, two of them chosen by each of the Spartan kings. In 491, however, Cleomenes’s Pythioi did not merely consult the oracular priestess and priesthood of Delphi. They also brought filthy lucre to bribe them to say what he wanted Apollo to declare, namely that Demaratus was a bastard: in the legal sense – not the legitimate son of his father, the late king Ariston. And, moreover, the Delphic officials allegedly accepted the bribe and delivered the desired verdict. In the short run, the ploy worked brilliantly for Cleomenes: Demaratus was declared a bastard by divine utterance and therefore deposed and replaced, and Cleomenes was free to return to Aegina, take Crius and other leading Aeginetans hostage, and force them to renounce their pro-Persian, or at least not anti-Persian, policy. It was for this that Herodotus praised Cleomenes to the skies, as one ‘acting for the common good of all Hellas’. However, the carefully woven plot then unravelled – disastrously for Cleomenes. The bribery was discovered, and the Delphians involved were dismissed from their posts. Cleomenes seems to have gone literally mad.

Herodotus says that he had always been slightly touched, not quite right in the head.* But the effect of the exposure of his extreme irreligiosity and his consequent self-exile to Arcadia was said to have been to make him behave so irrationally on his return to Sparta that the authorities felt they had to clap him in the public stocks. He was placed under the guard of Helots, but so persuasive was even a demented Cleomenes that he induced one of them to lend him his dagger. With that, he allegedly committed an appalling sort of hara-kiri, slicing himself into pieces from his feet upwards.

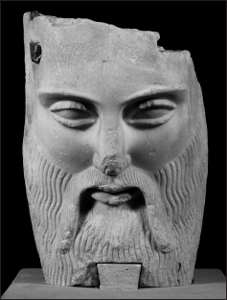

This damaged marble mask was found at Marathon; it belongs stylistically to the first quarter of the fifth century, which could well tie it to the famous Battle of Marathon in 490. It probably depicts a god, rather than a hero, and possibly therefore Pan, who crucially aided the Athenians by spreading his eponymous panic fear among the Persians and was awarded an official religious cult in return.

A huge amount was at stake in Cleomenes’s death: Sparta’s foreign policy and its standing with its allies abroad, and the health of the dyarchy at home. Not unnaturally, therefore, it has been suspected that Cleomenes did not actually kill himself but rather, having become an extreme embarrassment all round, was prudently done away with, possibly even by his own blood relatives. We shall never know for sure, but we do know the immediate outcome of Cleomenes’s death, which was the succession of his younger half-brother Leonidas. It is intriguing to ponder that, had Cleomenes still been alive and still king ten years or so later – he was only in his fifties when he died, in the early 480s – then we might have been celebrating not Leonidas, but Cleomenes, of Thermopylae.

The 480s in Spartan history are pretty much one vast blank in terms of evidence. The consequences of the Battle of Marathon, and of Sparta’s non-participation in that triumphant Athenian success, will have rumbled on. The Spartans might well have followed the internal politics of democratic Athens with great interest, and even been informed of developments as they occurred by their Athenian guest-friends. Increasingly in Athens, the various parties and factions adopted polarized positions on both domestic and overseas political issues, above all on the question of democratic institutions, and attitudes to Aegina and Persia. They resorted frequently to the new, democratic device of ostracism: this was a sort of reverse election, in which the defeated candidate among the most influential politicians was exiled by popular vote for ten years.

Soon after 485, however, the Spartans too were again being asked as a matter of urgency what attitude to Persia they should take.