SIX

THERMOPYLAE II:

PREPARATIONS FOR BATTLE

[The Spartans] are the equal of any men when they fight as individuals; fighting together as a collective, they surpass all other men.

‘Demaratus’ to Xerxes, Herodotus, Histories 7.104

THE CONQUEST OF GREECE would necessarily depend on cooperation between the Persians’ land army and the naval forces that would help, crucially, to supply it. Advance by land west and south from Doriscus, where in June 480 Xerxes had conducted the massive muster of his forces, was unproblematic if slow. All territory up to the northern border of Thessaly was already under the control of the Great King, and after the resistance coalition had abandoned its abortive notion of defending a Tempe line with ten thousand troops in July, Xerxes was able to make his stately way past Mt Olympus and through Thessaly unimpeded (except by his huge baggage train). The progress of the fleet was more chequered, but eventually it did reach Cape Sepias opposite the northern tip of Euboea as planned.

What should the reaction of the ‘Hellenes’ of the coalition be? If they were genuinely serious about putting up resistance, it was obvious where the next line should be drawn: at the axis between the pass (more accurately passes, as there were three) of Thermopylae, by land; and, by sea, at the point known as Artemisium (the site of a shrine of Artemis) at the north end of the island of Euboea. Some professional geologists and geomorphologists have sought to prove that Thermopylae was not the pass it was cracked up by the ancients to be; that Xerxes did not have to force this, but another, pass in order to proceed into central Greece. But if that were so, it is remarkable just how often the ancients, including many Greek natives as well as possibly benighted foreigners (such as a band of migratory and marauding Celts in 279), kept making this same stupid blunder.

However, there were other, manmade obstacles to the coalition Greeks’ conducting such a serious defence at this time, or conducting one whole-heartedly and in full force. Most conspicuously, allowance must be made in the case of the non-Spartan loyalists for a considerable ingredient of sheer panic fear that the Persian host was simply too large to be resisted, either at Thermopylae or possibly anywhere else. After all, the vast majority of the several hundreds of other Greek mainland cities had already voted with their feet and decided to join or at least not actively oppose the Persians rather than try to beat them back at any cost.

Fear of that sort is unlikely to have gripped the Spartans, however. They were war-hardened, and ever war-ready. For them, as we noted earlier, the requisite sort of martial bravery was a core value inculcated by formal public education from the earliest age, not something to be summoned up uncertainly to meet an ad hoc emergency. All the same, the situation facing them in summer 480 was the greatest emergency any Spartans had ever faced or would ever be likely to have to face. It threatened not just their lives and livelihood, but their very way of life.

Yet the Spartan force sent to defend Thermopylae was only about two-thirds the size of the one Sparta had just recently dispatched to, but withdrawn from, Tempe. The reason for sending what was advertised as only an advance guard was shared by all members of the coalition, though it was applicable to the Spartans above all. For the Olympic Games were due to be celebrated; these took place every four years, probably at the second full moon after the summer solstice, so sometime in August. This was a panhellenic religious festival, a major celebration in honour of the most powerful of all the Greeks’ gods, Zeus of Mt Olympus. So every four years the ‘Olympic truce’ was declared to enable any Greeks who wished to participate or spectate at Olympia to make their way to the site in the north-west Peloponnese in safety, immune from the usual risks and dangers of travelling through the territory of other and all too often hostile Greek cities. It would have been hard, therefore, for pious Greeks to divert their minds from their customary Olympic Games preparations.

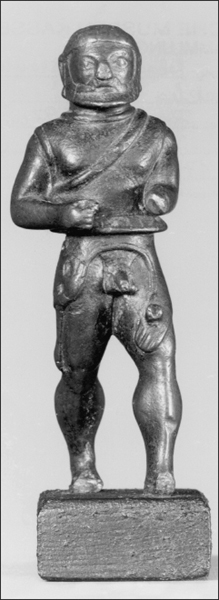

A sombre and bearded bronze Heracles, mythical ancestor of both Spartan royal families, wears his distinguishing lionskin and cuts a vigorously masculine military dash in this sixth-century Laconian-manufactured bronze figurine.

For the Spartans, and even more imminently, there was the further religious obligation to celebrate the annual Carneia festival in honour of Apollo, one of the main events of their religious calendar. All their principal religious festivals were dedicated to Apollo – the Hyacinthia and the Gymnopaediae as well as the Carneia; and the Spartans, as in the case of their non-appearance at the Battle of Marathon in 490, were exceptionally, indeed egregiously, scrupulous in their observance of such festivals. So they too felt they could not commit their full military strength to the defence of the pass at Thermopylae.

But ‘Greece’ desperately needed the Spartans, the coalition’s leaders, to act somehow, and to act effectively. They had to make at least some positive gesture of resistance, and if possible more than a gesture. There were several other factors, all religious or quasi-religious, that would have tugged the Spartans in favour of a Thermopylae defence. First, it was on Mt Oeta, not far to the west of Thermopylae, that their ancestral hero Heracles was thought to have met his end on earth before being borne away to a permanent afterlife as a god on the summit of Mt Olympus.* Below Mt Oeta to the south stretched the territory known as Dôris. Mythically, Dôris was the aboriginal home of the Spartans’ Dorian forefathers before they made the Great Trek south into the southern Peloponnese at least seven centuries earlier, as the fifth-century Spartans would have envisaged the timeframe.

The other quasi-religious factor favouring a firm Spartan commitment to defending Thermopylae was Delphi. On the council of the religious association known as the Amphictyonic League, the Spartans were represented only indirectly, as members of the Dorian people (ethnos). They took great pains to maintain a separate and direct hot-line to the Delphic oracle through the Pythioi, the four permanent ambassadors appointed by the kings.* In the lead-up to Xerxes’s invasion, the oracle had been issuing to the Spartans’ coalition partners in Athens a stream of negative, blackly tinged forebodings about the uselessness of resistance. To put it bluntly, the Delphic priesthood was medizing. Herodotus reports a similarly pessimistic Delphic response allegedly delivered to the Spartans. Either, it said, they must sacrifice the life of a king, or the Persians would destroy them and occupy their land. Many scholars have seen this as a classic case of vaticinatio post eventum, a prophecy after the event: the Spartans did in fact sacrifice a king, and their land was not occupied. They suggest that Delphi put out this invented oracle retrospectively both to show how powerful its prophetic powers were, and also to try to wipe away some of the stain of medism incurred by its earlier, pessimistic outpourings.

But if opinion in Sparta, as elsewhere within the coalition, was wavering somewhat in the summer of 480 – at any rate over the tactical issue of whether to meet Xerxes north of the Isthmus of Corinth, as opposed to at the Isthmus itself – then it might well have required some external authorization as powerful as that of the voice of Delphic Apollo to win the waverers round. It is my hunch that for this reason King Leonidas would have used his official contacts to engineer this oracle; not for nothing was he the half-brother of Cleomenes. He would then – leading vigorously from the front, as strong Spartan kings could – have made sure that it was he, not his co-king Leotychidas, who was chosen by the Assembly, on the advice of the Gerousia and the ephors, to perform the sacrificial regal role at the Hot Gates. It is no mere coincidence, I feel, that there is a distinct similarity between this act of self-sacrifice and that of Sperthias and Boulis in about 484, also on Leonidas’s watch.

For all these reasons the Spartans decided to entrust the defence of the Thermopylae pass, not to a commoner such as Eurybiadas (the coalition navy’s admiral of the fleet), but to one of their two kings. Characteristically, they gave this decision too a religious spin.

What do we know of Leonidas? The answer, sadly, is remarkably little – apart, that is, from what he actually did during those few hectic and climactic weeks of August 480. He was not destined by birth to become king at all, and did so only because his older half-brother Cleomenes I died without male issue.* The fact that he was married to Gorgo, Cleomenes’s only daughter, making him Cleomenes’s son-inlaw and indirect heir as well as half-brother, will have eased the succession, presumably. But Leonidas is likely to have felt that he had a lot to live up to, and quite a lot to prove besides.

On the other hand, precisely because he had not been expected to become king, Leonidas would have gone through the normal educational cycle from which the crown princes in each of the royal houses were – alone – exempted.† He will therefore have had a very good idea of Sparta’s ‘true interests’.‡ No less important, Leonidas will have shared the common Spartan warrior temper, of which the taskforce of three hundred appointed to serve under him at Thermopylae would represent the flower and acme.

Why, precisely, were 300 chosen, some four per cent of the total Spartan army of 7,500–8,000, and why these particular 300? First, 300 was a manageable figure for an elite taskforce, one that recurred elsewhere in Greek history at different times.* Second, the figure of 300 had strong symbolic and practical overtones in Sparta, as it was the fixed number of the regular royal bodyguard. The bodyguards were known as the hippeis (‘cavalrymen’), though in fact they served as infantrymen in the dead centre of the hoplite phalanx, where the commanding king would be stationed. They also performed a number of ceremonial or espionage functions off the battlefield. The three hundred hippeis were specially selected in an intense competition from among men in the ten youngest adult citizen year-classes, aged between twenty and twenty-nine.

Leonidas’s Thermopylae advance guard of three hundred, however, was to be selected with one crucial additional criterion. Besides being exceptionally brave, skilful and patriotic, each of the chosen few must also have a living son. In practice, since Spartan men typically did not marry until their late twenties, this is likely to have meant that at least some and perhaps many of the Thermopylae three hundred were aged thirty or over. As for their commander Leonidas, who by my calculations was aged about fifty in 480 and had apparently married Gorgo surprisingly late in life, he met the criterion imposed on the three hundred through his young son Pleistarchus.

The condition that each of the three hundred must have a living son – which is merely reported by Herodotus without further comment – has been interpreted variously in modern times. For some scholars, it was a device to ensure that they fought exceptionally well and bravely; but they were conditioned to do that anyhow. The reason, rather, was social – or, more precisely, societal. It was so that the sons would be there in place to carry on their father’s name, that is, to perpetuate their soon-to-be-dead father’s name and patriline. These particular sons would thus constitute an elite within an elite, the nucleus of the next adult generation’s star fighters, bursting with pride to emulate the feat of their late fathers. For the Thermopylae three hundred were to be in effect a suicide squad, of a peculiarly Spartan kind – entirely consistently with their upbringing and with the way in which Leonidas had conceived and pitched his own role. This was as peculiarly Spartan a thing to do as eating black broth in the mess.

Since 9/11 the issue of suicide/homicide in the name of a higher cause, sometimes also known as voluntary martyrdom (bearing witness, usually religious), has intensely and continuously engaged both the public media and the serious scholarship of the West. What makes the suicide/homicide assassins tick? Attention has focused naturally enough on Israel–Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Turkey and Chechnya, as well as those actions masterminded or inspired by Al-Qaeda (for instance, in Casablanca and Istanbul besides New York and Washington, DC). A number of possible generic motivations or explanations have been advanced – economic frustration and self-promotion to the posthumous status of hero and martyr, as well as religious devotion and political, especially nationalist ideology – together with, in individual cases, psychopathological disturbance. However, none of those suicidal/homicidal deeds was carried out officially and openly in the name of a legitimate state organization or governmental agency, no matter how much covert support they may have received from particular governments. The tactic is increasingly used for preference in civil wars. Nor are most of these actions at all discriminating in their targets, since they murder civilians and children as readily as armed combatants; and, unlike the fully adult Thermopylae three hundred, the perpetrators tend to be young men between adolescence and full manhood.

The nearest modern analogy, therefore, to the Spartans’ behaviour at Thermopylae – and it is by no means an exact one – is the officially ordered suicide hits by Japanese kamikaze (‘divine wind’, literally ‘spirit wind’) aircraft pilots, human bombs and manned torpedoes in the Second World War. These share with the Thermopylae action the motivation of an overriding commitment and loyalty to the good and the absolutely overriding dictates of the state, in the Japanese case those of the God–Emperor, and the belief that the enemy in some sense represents an overwhelmingly evil force against which tactics of last resort including the supreme sacrifice of self are entirely legitimate, in fact heroic. Also common to both are the notions that the spirit of resistance they symbolize may be as literally vital as the physical damage they inflict on the enemy, and that there is intense dishonour to be incurred through failure to carry out the suicide.*

They share also, even more importantly, an underlying philosophy – which is not by any means the dominant underlying philosophy of war in the West today. For most Westerners the point of war is to win – and survive. Western philosophy teaches by and large how to live, not how to die. But a key element of the Spartans’ world outlook was acculturation of the males from a very young age to the expectation of a non-natural, early death; indeed, their whole society was shaped so as to enable them to cope with this.† This is not entirely different from the Japanese bushido (‘way of the warrior’) honour code that prevailed under the ancien régime of the Samurai. It has been claimed by progressive Japanese intellectuals, such as the septuagenarian film director Yoji Yamada who has specialized in making Samurai movies, that this honour code makes no sense today, given its emphasis on death as the ultimate career move. But it would have made an awful lot of sense, I think, to the Spartans, and not least to Leonidas and his three hundred. The Spartans alone out of (all) the Greeks could have both conceived the Thermopylae vision of self-sacrificial suicide and gone on to carry it off to such stunning effect.

Besides the Spartiate (full Spartan citizen) soldiers, the Spartans automatically sent to Thermopylae a non-combatant complement of Helots, perhaps as many as a thousand in all, a couple of whom are individually mentioned by Herodotus. On the other hand, Herodotus fails entirely to notice or mention the 900–1,000 Perioeci, or ‘outdwellers’, who accompanied the Spartans, even though their presence is required to make up the global figure of four thousand Peloponnesians fighting at Thermopylae that he does report. These are mentioned by later sources, and they were presumably volunteers, like those who we know volunteered a century later for another Spartan campaign in northern Greece. Leonidas vetted them carefully, no doubt, both for their proficiency and, no less important, for their morale. Nor does Herodotus report the alleged medism of Perioecic Caryae in northern Laconia on the frontier with Arcadia. If the allegation were true, it would add a spicy extra dimension to Spartan deliberations over the wisdom of committing large numbers of Spartiates outside Laconia, let alone outside the Peloponnese.*

The women of Sparta were considered exactly the non-military half of the population. But, as Herodotus was the first to emphasize in a historical work, they were nevertheless a vital ingredient in Sparta’s overall military comportment and profile. They also achieved wide fame – or notoriety – elsewhere in Greece for not being properly feminine. According to one of Plutarch’s Laconian Apophthegms, Spartan wives and mothers were in the habit of barking the peremptory command, ‘With it – or on it!’ to their husbands or sons, as they were about to set off on campaign. ‘It’ was the warrior’s hoplite shield. The men were either to come back alive, with their shield (to throw a shield away was a major hoplite crime), or to come back gloriously dead, carried upon their shield by their comrades. That phrase echoed throughout antiquity. It was seen as encapsulating the Spartan women’s fighting spirit and their total internalization of Sparta’s martial – and overrridingly masculine – values. It was in the same vein of anecdote that Gorgo (wife of Leonidas, daughter of Cleomenes I) was once allegedly asked by a critical – or envious – non-Spartan woman, ‘Why is it that you Spartan women alone rule over your men?’ Gorgo adroitly evaded the question and shot back, ‘Because we Spartan women are the only women who give birth to [real] men’!*

One of the most prominent of these real men was Spartan ex-King Demaratus, between whom and Xerxes Herodotus stages two revelatory discussions on the subject of the Spartans in the run-up to Thermopylae. At the first of these, supposedly immediately after the description of the Doriscus muster, Xerxes asks Demaratus ironically, expecting the answer ‘no’, will the loyalist Greeks have the guts and gumption to ‘raise their arms against me and resist’? Before answering his lord and master, Demaratus makes great play with the notion of truth; this was an idea that was dear to the Persians from their upbringing, and to none more than the Persian Great King, who was the sworn and (as noted) declared enemy of ‘the Lie’. Does Xerxes want the truth, Demaratus replies, or merely to be humoured? Here Herodotus captures very well the flavour of any such encounter beween a courtier and the immense majesty of the Great King, who had the power to swat like a fly even the greatest of his subordinates – a Mardonius, say – since all alike were equally ‘slaves’ in his eyes. But Herodotus has a further agenda too – dramatic, indeed tragic, irony. For Demaratus will tell Xerxes the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and yet – Cassandra-like – he will not be believed.

Demaratus begins by stating his supreme respect for the Spartans, out of all the Dorian Greeks. Partly this reflects the fact that most of the Greeks who would stand up to Xerxes were Dorians. But it was also a way of diminishing the impact of Demaratus’s formal treachery to his native city of Sparta. He then spells out that what he will say applies solely to them. His eulogy is bestowed on two grounds. First, ‘they will never come to terms with you and so bring slavery to Greece’. Second, the Spartans will not merely resist but will fight as no others, no matter how few against however many. Xerxes has a bit of a laugh and a smirk at this, on the grounds of the immense disparity of numbers between his forces and the Spartans. He concedes that maybe, with the judicious application of the whip, ‘a few might hold out against many’, but even if the numbers on each side were equal, he would still back the Persians to win.

One is meant to notice the Great King’s elementary, ethnocentric error. The Spartans, as Herodotus’s readers would have needed no reminding, did not have to be whipped to make them fight with all their might, even against the most massive odds. Whips were only for slaves, not free men; they were appropriate for a barbarian master to use on his slave subjects, but out of the question for the citizen soldiers of a free Greek polis.

Demaratus counters with two knockout ideological punches. First, the Spartans ‘are the equal of any men when they fight as individuals; fighting together as a collective, they surpass all other men’. Second, the reason the Spartans will resist is that they have made a conscious decision to obey not any one human, let alone an absolute dictator (such as Xerxes), but the Law (nomos): both the individual laws and customs that they themselves make, and the general concept of the political obligation to be law-abiding. The most relevant law in this particular case, according to Demaratus, is ‘not to retreat from the battlefield even when outnumbered, to stay in formation, and either to win or to die’. Demaratus even tells the Great King, unbelievably to Xerxes’s ears, that the Spartans fear Law as a despotês (‘master’) far more even than his subjects fear him.*

What Demaratus is therefore saying on Herodotus’s behalf is that there was an unbridgeable gulf fixed between the kind of political system and authority embodied personally by Xerxes and the kind represented by Sparta. Since Sparta’s system stood for freedom, it follows that the Great King’s stood for slavery.† Xerxes, for once, Herodotus tells us, did not get angry with Demaratus for speaking his mind plainly, and tried to turn their dialogue of the deaf into something of a joke. But it was the Spartans who would laugh last and longest.

Their second supposed interview is related in the immediate prelude to the story of the fighting at Thermopylae itself. While Xerxes had his troops drawn up and waiting just outside the western end of the pass, he sent a mounted Persian scout to spy on the Greeks’ behaviour. The Greeks he observed happened to be Spartans. This was the incident in which, utterly astonished and bemused, the Persian reported back to an equally bemused and astonished Xerxes that the Spartans were engaged either in gymnastic exercises or in combing out their (exceptionally) long tresses.

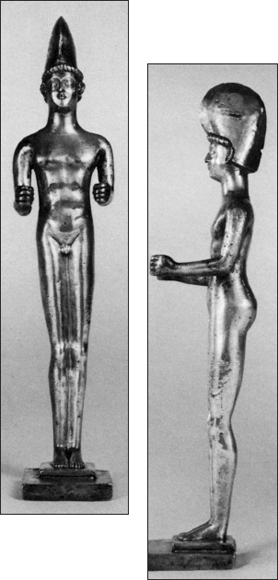

An extraordinary collection of precious objects from what had once been a major local religious shrine on the Oxus (Amu-Darya) River in Tajikistan in central Asia (part of ancient Bactria) found its way to the British Museum via Afghanistan and Pakistan in the late nineteenth century; this presumably fifth century silver statuette of a heroically nude youth wearing a tall headdress of Median type is perhaps a Greek-inspired local work.

Ancient Greek males famously practised their physical exercises and competitive athletic sports fully nude – hence the name given to the place where they practised and worked out, the gymnasium.* Such nudity was shocking to a non-Greek oriental. It was another of those cultural markers of otherness via which the Greeks persuaded themselves of their cultural superiority to all ‘barbarians’.

As for the Spartan men’s long hair, that was sufficiently unusual among Greeks, let alone Persians, for it to cause comment. Most Greek males cut their hair short, or shorter, on attaining puberty or full civic manhood. The Spartans, by contrast, chose that moment of socio-sexual passage from one status to another to let the hair grow, precisely as an outward and visible sign of adult male warrior status. Various rationalizing explanations have been offered, both for the cause and for the origin of the practice’s adoption, but its symbolic meaning was most likely the most significant: real men grow their hair long. The Spartans’ wives, in symmetrical inversion, had their hair shorn on marriage and kept permanently short thereafter.

The Persians too, or some of them, had long hair. But on the brink of a fight to the death was no moment for Persians to be seen coiffing it in public. Xerxes allegedly could not believe that a bunch of gymmad cissies would cause him much trouble in battle. But the coiffure’s symbolism and its combing out were decoded for Xerxes by Demaratus, who told him it meant that the Spartans had resolved to fight to the death. The Great King’s total failure to grasp the Spartan mentality and the import of key Spartan social customs was Herodotus’s way of foreshadowing his ultimate defeat and of throwing doubt from the start on the wisdom of such an unsoundly based enterprise.

For the other Greeks of the coalition at Thermopylae there were other locally specific factors at work besides the common excuse – the imminence of the Olympic Games – for sending only an advance guard. Out of the twenty-five thousand or so fighting men potentially available, the Peloponnesians sent only about four thousand.* No doubt this was partly due to their reluctance to commit troops beyond the Isthmus of Corinth, outside Fortress Peloponnese. But loyalist Greeks from north of the Isthmus were also present in very small numbers at Thermopylae. There were no Athenians at all on land there (though there were many thousands with the fleet at Artemisium), nor Megarians. More controversially, there were only a few Boeotians, including a mere four hundred from the Boeotians’ principal city of Thebes.

Later, after Thermopylae, all the Boeotians except Thespiae (an enemy of Thebes) and Plataea (an ally of Athens) medized, so that when the Persians were eventually beaten back in 479 the Thebans’ reputation was besmirched.† But was this entirely fair to the four hundred Thebans present at Thermopylae? Were they there, as Herodotus’s version has it, only because Leonidas had compelled them to be, as hostages, of a kind, for the loyal behaviour of their compatriots back home? If we follow sources other than Herodotus, a quite opposite view emerges.

The Thebans of the 420s, the grandchildren of the men of 480, had a different explanation – or plea of mitigation – for their ancestors’ unpatriotic behaviour, as reported by Thucydides. Thebes then, they said, had been ruled by a narrow oligarchy – somewhat akin, perhaps, to the Aleuad dynasty of Larissa in Thessaly who had been prominent and proactive medizers – whereas since the 440s Thebes, like the rest of Boeotia, had been governed by a more broad-based, and much more politically moderate, oligarchy. Other sources, including the Boeotian Plutarch (from Chaeronea), went even further in their rehabilitation. Plutarch was incensed by what he took to be Herodotus’s anti-Boeotian prejudice. For him, it was these four hundred Thebans who were the true patriots. Being opponents of the ruling regime in Thebes, they had volunteered to serve under Leonidas. It is not easy to decide between these two diametrically opposed versions of the four hundred Thebans’ presence. Apart from them, there were certainly present about a thousand troops each from the two local Greek peoples most directly affected, those of Phocis, and those of Opuntian Locris. The not very grand total of Greek resisters was perhaps some seven thousand in all.

No doubt the Thermopylae operation was generally seen very differently by the other Greeks present than it was by the Spartans. Herodotus actually reports that even as late as when they first clapped eyes on Xerxes’s horde a panic-stricken parley was called to discuss whether it might still be prudent for them to beat a retreat. Even Leonidas is said to have had some sympathy with this view, until he was swung back to his original intention by the anger of the Phocians and Locrians. Implausible as that report is,* many of Leonidas’s non-Spartan troops probably believed at the outset that a brave resistance at Thermopylae would be followed, for the survivors, by an honourable retreat in order to fight or die another day.

Another factor caused them all legitimate alarm. The Tempe line had been abandoned when it was learned that it could be outflanked fairly easily by not just one but two other passes. It was now learned from the local Greeks of Malis that Thermopylae too could be turned, by a single path (or trail) called Anopaea. This snaked over Mt Callidromus to the south of them and emerged somewhere near the East Gate. Anopaea was, however, a path, not a pass, and wide enough, in places, only for single-file human traffic. One of Leonidas’s first decisions on the spot was to attempt to seal this potential gap. He detached the local Phocian contingent of one thousand in its entirety to guard Anopaea. These were men familiar with the terrain and conditions and who had immediately the most at stake and to lose. Had Leonidas had the spare manpower, he would probably also have sent a Spartan officer to command them, according to the normal procedure of the Peloponnesian League. But at Thermopylae precious little was normal.

For all the ifs and the buts, the shilly-shallying and the recriminations, the Greek coalition did indeed mount a serious defence at Thermopylae; and thereby – after a build-up lasting at least four years – finally precipitate the first serious head-on encounter between the Persian invaders and the resisting Greeks. The season was by now high summer, and the Gates were shortly to become Hot in more senses than one.