Born on September 3, 1934, in Gilmer, Texas, Freddie King’s stature has grown in full measure since his premature death in 1976. Moving to Chicago in the early ’50s, King fell into the burgeoning blues scene and learned guitar in the clubs. King’s first record, “Country Boy,” was a duet with Margaret Whitfield on the small El-Bee label in 1956. He signed with King Records in 1960 and released a succession of hits, many of them catchy up-tempo instrumentals, including “Hide Away,” “San-Ho-Zay,” and “The Stumble.” King relocated to Texas by the mid-sixties, and after appearing at the Texas Pop Festival in 1969, his reputation in the U.S. rock scene grew after recording with rock luminaries Leon Russell and Eric Clapton. Unfortunately, King was not well served on the reissue market until the 1993 Ace Blues Guitar Hero compilation and the more recent Bear Family box set, Taking Care of Business, 1956–1973, that appeared in 2009, spurring King’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012.

In the following interview, author Mike Leadbitter reminds readers of King’s Chicago influences on both his guitar and voice. King’s sound is best understood in comparison with his Chicago woodshedding influences—namely, Eddie Taylor, Jimmy Rogers, and Robert “Junior” Lockwood. Leadbitter also notes that King’s vocal style resembles Buddy Guy more than the smoother style of a T-Bone Walker. This comparison to Chicago performers highlights that the birthplace of an individual is nowhere as impactful as the influences upon an artist in their formative years when applying themselves to the craft.

This interview also marked the end of an era at Blues Unlimited. Mike Leadbitter became sole editor of the magazine in 1973 and juggled that job while simultaneously editing a new British music journal, Let It Rock, covering jazz, country, and soul. This article appeared in Blues Unlimited issue 110 in October 1974 as Leadbitter’s last interview published in the magazine. He died just one month later.

—Mark Camarigg

Madison Nite Owl Freddie King Interview

Mike Leadbitter

Blues Unlimited #110 (Oct./Nov. 1974)

Though somewhat out of favor with his followers at present, 40-year-old Freddie King remains cheerful, taking life as he finds it. As far as he’s concerned, he’s just a straight blues singer and likes nothing better than reminiscing about the good old Chicago days when there was a blues joint on every corner and men like Elmore James, Muddy Waters, and Eddie Taylor reigned supreme. He might live in Dallas today, but the Windy City has a strong claim on his soul and that’s where he learned almost everything he knows about a guitar.

He knows he’s good and refuses to let modesty stand in his way when recalling with glee how he would go around “cutting heads” on Sunday afternoons. He once liked nothing better than the chance for a guitar battle, but became notorious for the speed with which he dispatched opponents. This caused lesser men to hurriedly leave the stage as soon as they saw his bulk heave into sight, and legend has it that even Blues Kings paled when he and Earl Hooker entered a club together. Such incidents, however, took place in the early sixties—the chart-busting days—when Freddie, as a musician, was at his peak. The preceding years were as tough for him as they were for anyone else.

Like most of his contemporaries, Freddie King is just a plain old country boy. Born on a farm outside Gilmer, a small town near Longview, Texas, he was raised in a rural environment and his first experience of city life came at the age of 16, when he defied migratory patterns and moved North East rather than West. Shaking with cold, he arrived in Chicago during the December of 1950, clutching a Harmony guitar and wishing he’d never left the South. But he had little choice in the matter: his mother was determined to join her relations in that town.

Freddie’s grandmother lived on the West Side and the King family settled there at Bishop Street and Adams. The first thing they all had to do was find work, but big for his age, Freddie had few problems. He just said he was 18 and was quickly hired by a local steel mill. In spite of getting his legs scarred in an accident, he stayed on at the same place for seven years relying on the money earned for the buying of new guitars and other fresh and exciting indulgences. Then, amazed by the amount of music to be heard in his new home, he really fell in love with the blues and at night ran wild, walking the streets to hang out at neighborhood bars though well under age. Wherever there was music you’d find him, and during 1951 he began to polish his technique, borrowing freely from men like Eddie Taylor, Jimmy Rogers, and Robert Jr. Lockwood while developing a pretty unique blues style first learned in Texas. In the habit of really hitting the strings on his acoustic box in an attempt to achieve more volume, he found it difficult to come to terms with electric models and eventually found himself abandoning the softer, mellower, yet amplified approach of his heroes in favor of the harsher more astringent sounds beloved by other youngsters of his age. His became the “new” Chicago blues and he would join the ranks of Magic Sam, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, Syl Johnson, and so many others, building his reputation alongside theirs. How this all came about is quite fascinating and best left to Freddie to explain.

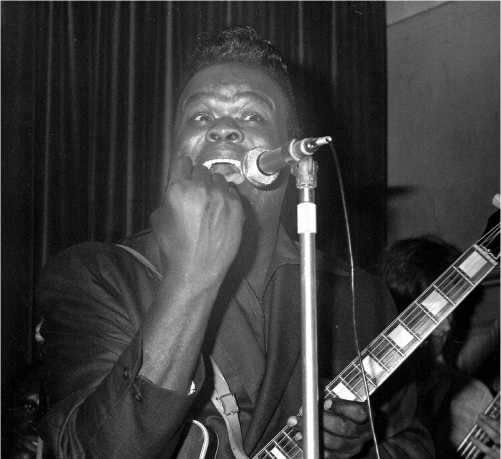

Freddie King, 1960.

We always kept two or three guitars around our house in Texas all the time. They all played—my mother, my uncles, they all played guitars. Leon King—he got killed in a car wreck when I was 11 years old—he taught me a lot of stuff. I played in church and in school—there was nothing going on in school that I wasn’t in. Lots of guys played around there. There was one guy about the same age as my mother. They called him Shorty, Shorty Brown. He was a piano player and every time they give something like a minstrel show in school, they got him to play piano. He and I would play together. He could dance, too, and he’s still living in Longview.

I’d always go to Chicago when school was out, after I started high school. My grandmother, my mother’s brothers and things, they lived there. So when I finished school, after I was 16, we all just went there. I was playing like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Muddy Waters when I got to Chicago, but Jimmy Rogers and Eddie Taylor were different. They really inspired me. I stayed around them all the time. Every time they look up, I’m coming. If I couldn’t catch one, I’d catch the other. They’d say, “Don’t you ever sleep?” There was a guy in Chicago, identical to T-Bone Walker, L. C. McKinley. He was playing the same stuff and he used to go as “T-Bone Jr.,” but, see, I wasn’t thinking too much of that, because I wanted to play like those other two cats. That was the style I wanted to play in. Open key of “E” or “A.” Those were the only keys I played in then. Those clamps—capos—used to call ’em “cheaters”—I seen where they changed keys with them. So I went and bought me one. Same thing Eddie was doing, I was doing, too.

Eddie was playing at the Kitty Kat on Madison Street then with Willie Foster and Floyd Jones. I’d go in there, but so many people crowded in, the cat told me not to come in anymore as I was under age. His name was Mike, too. But I’d slip through all this crowd anyway and make my way around to the bandstand, where I could sit and just watch Eddie. And then I was at a backyard party once and he brought his whole band down there to jam some numbers. So Eddie was showing me how to play in “E” and I said to him, “Say, man, where you live?” He acted like a fool and gave me his address, and after that I was up his house so much they thought I lived there.

See, after that I worried Jimmy Rogers at the clubs. He was showing me how to use these picks. He was playing with Muddy Waters and in intermission he’d go to walk off and I’d grab him, make him show me this and that. And then there was Robert Jr. Lockwood. I worried him pretty bad, too, but you couldn’t really worry Robert Jr. He liked helping people. He loved showing people. Now, this is when I really got into the T-Bone Walker, B. B. King style. Robert had a weird sound like them and I wanted to learn some of that, too. So we got to talking and laughing and he was showing me how to make these chords and Johnny Shines did, too. They said if I could play in the keys they showed me, I could get rid of the clamp—throw the son of a bitch away. They showed me how to play without it. I’d sit up all night practicing, but it was hard for me to do that. But finally, I caught on to it.

I was 17 when I got my first electric guitar, and Willie D. Warren (mistakenly referred to as “Willie Wine” in earlier Freddie King articles) signed for it (acted as guarantor). It was a Kay, but it got stolen and then I turned around and got me another one. A Sunnyland guitar—they’re made by Kay too, but that got stolen, too. And I lost my amplifier at the same time. So then, I got me another one. A friend, Lee Edward Brown, signed for me to get it. He worked for the Curtis Candy Company, he didn’t play anything. I kept that one for about a year and then I got me a Les Paul (Gibson) and that’s when I was playing with Earlee Payton—’56, I started playing with him.

The first guy I ever played with was Sunnyland Charles at a place called Red’s Playhall on Madison. He was with a harmonica player named Johnny Dee—really good harmonica player. Charles plays guitar and, really, his was the first electric guitar I played. When I first met him he had some cousins living in the same building as me, and he came in there with his guitar and I said, “Let me see your guitar.” He said, “Come go with me,” and he taken me to a club called the Spot. It was on Maple and do you know who was playing there? It was Johnnie Temple and Baby Face Leroy. I’d never played electric before, but Charles said, “Get up there and play one.” I said, “I’m not good enough to play with those cats, man,” but they pulled me up there anyway. A couple of months later I met Charles again and he said, “Hey, man, I’m playing down on Madison there. Why don’t you come by?” So I started playing with him. I was 17 years old.

About a block down from where Charles was playing at Red’s was the Kitty Kat. I met Sonny Cooper there before I did Sonny Scott. See, I’d go from Red’s to the Kitty Kat, and on down the street from there was Ralph’s Club, where Memphis Slim was playing, and he had Lee Cooper (guitar) with him. They had a really good band, but on every corner at Damen and Madison there was a band playing. There was the Cedar Club, the Royal Revue—King Kolax was there. And over the other side of the street was the Paris Club, where Danny Overbea was playing. Then I’d go over to Lake Street—go straight across—and there’s Elmore James playing over there. Elmore had Johnny Jones’s band. There was Ernest Cotton, Boyd Atkins blowing the horns, and then there was Odie Payne. But Odie was working with Jimmy Rogers for a while, and they used Kansas City Red until he came back. Didn’t have no car then. I was walking, man, I was always walking. I wasn’t frightened of anything. They call it skid row down there, but it was home to me.

After Sunnyland Charles, I was with Sonny Scott (drums) at Red’s Playhall. Me, Sonny, and Jimmy Lee Robinson (bass). This was in ’52. Then I went to Sonny Cooper (harmonica). There was me, Willie D. Warren (bass guitar), and Jesse (drums). This was at the Kitty Kat, but after it closed up, we moved down the street to the Be Bop Club, which was owned by the same people. So all of us started playing down there. We really didn’t have no band then, we was just jamming with each other and stuff. Then I started back to playing with Sonny Scott and Jimmie Lee and we got a good thing together then. This is when I really got into playing lead, ’cause I didn’t have a harmonica or anything to help me out. I had to just stand out in front and really keep everything covered up. This is when I really learned to finger and bend and put stuff in there like I’m doing now. I didn’t have no help.

I was playing with Scott when I first met Payton. We was playing cocktail parties then, and on Sunday afternoons we’d play at the Stadium Sports Club, right in front of the Chicago Stadium. One band would play there awhile and then another band would get up and play awhile, you know. Payton came in with his band one day, and after I met Payton I started playing with him at the Heatwave, upstairs on State Street. I played with him one night there, on a Tuesday, and on Sunday afternoons we played at the Cotton Club. They had two Cotton Clubs—one on the South Side and one on the North Side, and the owner was Youngblood, a piano player. Count Basie and Joe Williams was there, and they didn’t have no blues until we came in. We packed ’em in. So at first I was playing two days with Payton and I had my regular thing with Scott and Jimmy Lee. Then finally I went with Payton (full-time). Smokey Smothers was with him—he joined a little before I came—and he (also) had Mojo Robert Elem (bass) and T. J. McNulty (drums). I guess I played with Payton longer than with anyone else. I was with him about a year.

That lady, Miss Margaret Whitfield, owned the Ricky Show Lounge. She recorded us in ’56 and the record was supposed to have been leased to Chess. But there was some trouble with the union along there, so Chess didn’t want no part of it and we let (lawyer John) Burton have it. That wasn’t me playing guitar on it. No, it was Robert Jr. Lockwood, and Billy Emerson was on piano. The record didn’t do a thing on account of the trouble they had, but really it wasn’t a very good record, was it? [Note: Freddy is referring to El-Bee 157—“Country Boy”/“That’s What You Think”—issued under his name. Margaret Whitfield is also heard on side one, and the other sidemen were Earlee Payton (harp), Mojo Elem and T. (Thomas) J. McNulty.]

Then I went with my own band—I didn’t go back to Texas until 1963. Mojo and T. J. came with me from Payton’s band, and we played with just the three of us for about a year in ’58. But then I got a big band. We got Abb Locke, saxophone player; Hal (Harold) Burrage played piano; and for a while Lil’ Mason was singing. And John McCall was another vocalist I had and so was Dee Clarke. We stayed together until I started recording in 1960. We played the Casbah on the West Side and Mel’s Hideaway Lounge and the Squeeze Club. Mel’s was on Loomis—Magic Sam and all of us used to play there. We also played the Happy Home—that was on the West Side, too—and Willie Mabon and Eddie Boyd also played there. In ’58 I just quit work (at the steel mill). I was playing music every night and averaging about $300 to $500 a week after I’d paid the men off. I was charging $500 for a big club dance then, ’cause my band was really popular.

I’d been trying to get with Chess for two or three years (when I signed with Federal), but they wouldn’t record me, because they said I sounded too much like B. B. King. But they used me on sessions. Then I’d been knowing Syl Johnson since ’56, and he introduced me to Sonny Thompson, who was working for Federal (King’s subsidiary). Syl recorded for Federal before me, but they sort of lost interest in him after I came along, and I wasn’t very happy about that, ’cause we had been friends a long time. I knew Mack (Thompson), Syl’s brother, before I knew Syl. Also Jimmy Johnson is his brother, too. Jimmy has records, too. All three of them used to play together. When I made the first four hits, Syd Nathan (owner of King-Federal) was nowhere around. He was upstairs, but he didn’t come down. We got a good sound and Sonny Thompson was a great blues player. The others (on the session), Bill Willis (bass), Philip Paul (drums) and them, was all studio musicians. They lived in Cincinnati.

On August 26, 1960, Freddie went into the King Studios in Cincinnati with Sonny Thompson and cut six titles. Amazingly, three became hits: the haunting “Have You Ever Loved a Woman,” superbly sung and played; “See See Baby”; and the driving “Hideaway,” a fine instrumental dedicated to Mel’s Hideaway Lounge. The following year, on January 17th and 18th, he returned to Cincinnati again to record two more chartbusters: “I’m Tore Down” was one and “Lonesome Whistle Blues” was the other. An April date then produced “San-Ho-Zay” (San José) and July brought forth “Christmas Tears.” When 1961 ended, Freddie had six R&B Top 10 hits under his belt and was the new blues sensation. Such phenomenal success took him straight out of the taverns and onto the one-nighter circuit.

Sonny Thompson put me on one-nighters after “Hideaway,” and my first gig, my first stop, was New Orleans. From New Orleans to Texas was my first tour, but going to New Orleans was like going home. Those guys down there were beautiful cats. I checked in a hotel that was owned by a saxophone player with Tommy Ridgely—Mel’s Motel. It was two miles out of New Orleans on Shrewsbury Road. Just me and a driver, we drove down from Chicago, and I was very tired when we checked in. The lady there, she said, “Is that your picture there?”—it was an advertisement for the show—and she said, “I think my son is going to play behind you.” And the next day, here come all these cats. There’s Thomas Ridgely, Ernie K-Doe; there’s Al Tousan (Toussaint), Lee Dorsey, Danny White, Earl King, and “Shine,” Alvin Robinson. All these cats, man, just ganged up. And I was playing the same show with Thomas Ridgely and Earl King. I played around New Orleans for about three weeks before I went to Texas, and then I played Dallas, Waco, Houston, and San Antonio. And then I said, “Shit, we got more dates, but I’m going home.” I had to get a new car when I got back. The one I had was burned out with all that traveling. I was with Shaw Artists then. Shaw had everyone then.

When I left on the next tour, Tyrone Davis was driving for me. I went on a big tour then, there was a whole lot of people. Me, Jimmy Reed, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Smokey and the Miracles, Shep and the Limelites, Chuck Jackson, Bobby Peterson … all of us had hot records out. It was called the Dee Clarke Show—he was the main attraction. We traveled in cars—each of us to his own car. We did two numbers each night. That’s all we had time for—there were so many of us—and we got $250 a night. I did 50 of those one-nighter tours at $250 a night. There were all Shaw shows. Shaw were making money off us (at the box office), plus getting a percentage (of our earnings).

Unfortunately, as far as the charts were concerned, 1961 was Freddie’s first and last big year and the one-nighter circuit rapidly wore him down. Though he continued to record prolifically and saw a flood of albums released, he just couldn’t get another hit to keep him in the public’s eye. This wasn’t his fault, as he continued to come up with excellent, highly commercial material. The blame for his rapid demise rests with the late Syd Nathan. For some obscure reason, Nathan upset some deejays during the mid-sixties and they refused to play his product. This ban became national and had still not been lifted when I visited the company in 1973. Without airplay, all King artists, even James Brown, suffered and the lunatic situation did more to bring the company to its knees than anything else. Nathan, then a rich man in failing health, died refusing to back down and resolve the matter.

Freddie King. London, October 9, 1967. (Photo Bill Greensmith)

In 1963, Freddie, tired of city life and touring, returned to Texas, buying himself a home in Dallas and settling down with his family. Having completed a mammoth session for Federal in August ’64, he stayed away from the studios for over two years and then signed for King itself in September 1966. One date resulted from this final association with Nathan and then he quit to join Atlantic in ’68. Lonnie Mack’s band and Dallas drummer Frank Charles provided the small combo backup that he was used to for the ’66 session, but, regrettably, Atlantic began recording him with a big band and the results weren’t so good. A couple of albums and two singles were issued by Cotillion, an Atlantic subsidiary, but little notice was taken, even though Freddie was by then a popular figure in Britain thanks to regular appearances on the pub-club circuit. Dropped by Atlantic in 1969, he eventually landed up with Leon Russell’s Shelter label and was marketed B. B. King–superstar fashion for the first time. He refuses to talk about those days, but is very excited about his new RSO contract and seems to enjoy working with Mike Vernon, who at least understands and appreciates him for what he is, and not for what he could be if this, that, and the other were added.

Freddie King’s big problem is that he seems doomed to endless comparison with B. B. King. When he first rose to fame it was assumed that he had been vastly influenced by B. B., and writers (including myself) took it for granted that as he’d come from Texas, T-Bone Walker played a significant role in his musical development. No one really looked upon him as someone apart—a Chicago artist, in spite of his background, possessed of an extraordinary ability to churn out fine blues instrumentals or vocal performances of great individuality. Though he performed in the popular style of the day, Freddie was instantly recognizable. If one has to seek influences, then his early vocal work owes more to men like Buddy Guy—“Have You Ever Loved a Woman” being a perfect example—than anyone else, but instrumentally, he’s pretty unique. B. B. King’s influence, such as it is, is therefore indirect, not direct.

King-Federal released 77 titles by Freddie via singles and albums, and of these, 30 were instrumentals and four were duets with Lulu Reed, Sonny Thompson’s wife. To my permanent surprise, none really disappoint, though the instrumentals have an almost predictable monotony at times and the same high standard of 1960 is maintained throughout. Freddie’s soft, strained voice is ideally suited to the songs he chose to sing, and his often jaunty approach to 12-bar blues provides a rocking swing missing on many records by his rivals. He also makes the whole guitar work for him, appearing to be as deft with the bass strings as with the treble ones, and comes up with a beautiful, clean, yet funky sound at all times. Next to Jimmy Reed, he was Chicago’s most popular export during the sixties, and it’s a pity the city had to lose him.

Freddie, a musicians’ musician, has long been admired in France, but never really got the attention he deserved from blues enthusiasts at the time when he was really big (this is the first time BU has devoted a whole feature to him). Though he influenced several British R&B guitarists of the era (who were of no consequence to those who knew, but obviously more aware), it has only been in recent years that his Federal work has achieved collector status. Oddly enough, the probable reason for this is that he was just too popular, too commercial, too readily available to suit our passion for the obscure. Smokey Smothers, a longtime friend of Freddie’s, suffered a similar fate, although he gave us one of the finest blues albums ever and a tremendous, though small, collection of singles. Freddie was dismissed in 22 short lines by Chicago Breakdown—poor Smokey only got a name check. It wasn’t the author’s fault—his main preoccupation was with the dead past, not comparatively recent events or the future, and he gave us what we wanted to read.

Whatever future there is, Freddie will be around to share it. He’s still young, in his prime, and has lost none of his creative skill. In fact, his career, such as it is, has hardly begun. He can’t be expected to return to square one and rework the initially successful formula, but his output for Shelter indicated that he can survive as an individual even in the midst of a super group. Confused by demands that he be a today bluesman, rather than one of yesteryear, he now finds it hard to keep up with very different audiences. Should he play the guitar behind his head and rock the joint with “Hideaway,” or should he be cool, yet intense, and do “Woman Across the River”? A difficult choice and in the last couple of years we’ve all suffered from his mistakes. Perhaps it’s just that he’s tired of bopping around, sweating profusely, doing the same old jive year in and year out? Perhaps he wants to be known for something new, rather than remembered for something 14 years old? Who can tell? Whatever, he’s determined to remain true to himself and keep making music, and that, after all, is more important than anything else.

Marcel Chauvard and Jacques Demetre, the first people to interview Freddie (1959), provide the following details on artists mentioned in this feature. Between 1957 and 1960, Sunnyland Charles (or Chas) worked with the Globe-Trotters at the Globe Trotter Lounge on Madison. Other members of the trio were Gene Dennis (harp) and Johnny Mae Dunson (drums). Nothing has been heard of him since. Frank “Sonny” Scott plays drums, harp, and guitar. Born at Houston, Texas, on June 21, 1927, he appears to spend his time between Chicago and his hometown, where he once ran the Great Scott label. He claims to have recorded for Duke (unissued titles) and was with Big Jay McNeely’s band in June 1959. Sonny Cooper was born on March 8, 1926, in Jackson, Mississippi. He claimed to have recorded for Parrot in 1953 with Freddie, Jimmie Lee Robinson, and Willie Warren and for Chess. Freddie remembers backing him on a Chess session that resulted in “Your Love Is Like a River Boat,” a song that remains unissued. In October ’59, Cooper was working with Eugene Williams (guitar) and Hayes Winkfield (drums).