Born on March 22, 1932, near Bellville, Texas, Weldon “Juke Boy” Bonner personified the modern bluesman whom writers and staff of Blues Unlimited greatly respected. The itinerant bluesman never enjoyed sustained success, but made his mark as an important blues scribe with songs like “I Got My Passport” and “I’m Black and I’m Proud” addressing modern struggles and civil rights issues facing black Americans.

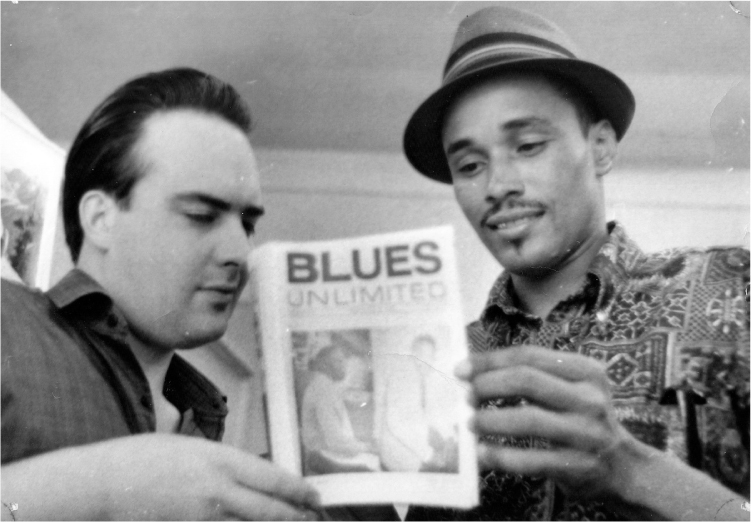

Bob Geddins first recorded Bonner as “Juke Boy Barner” for his Oakland, California–based Irma label in 1957. Bonner later recorded for Goldband in 1960, billed as a “one man trio.” These early sides never hit and Bonner’s career stumbled when he was hospitalized with severe stomach ulcers in Houston in 1963.

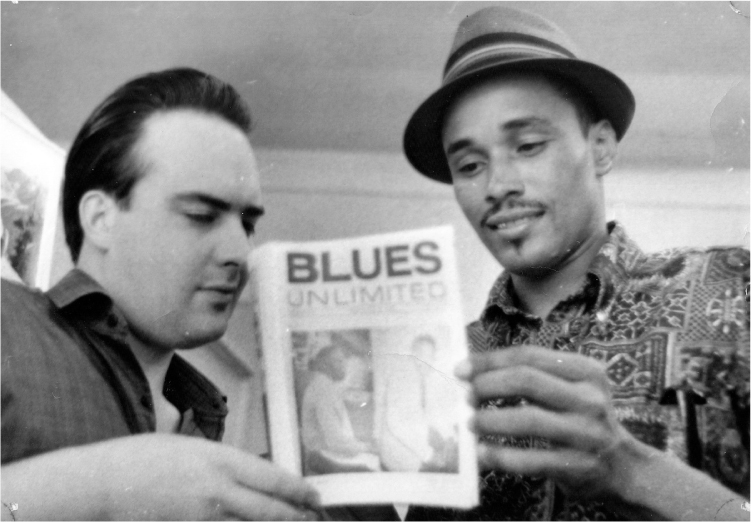

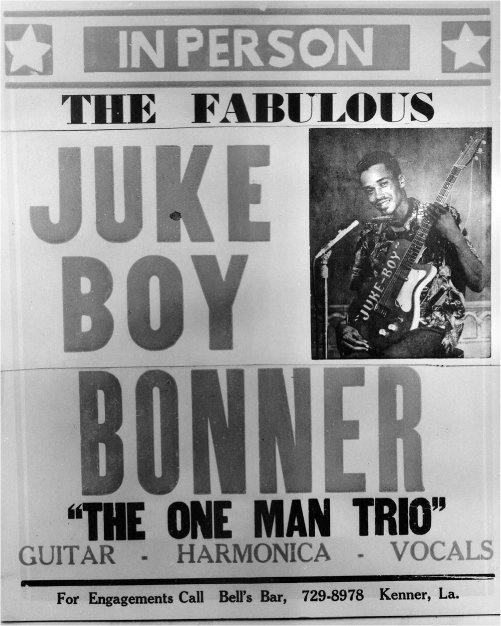

Mike Leadbitter made his first trip to the United States in May 1967 and stayed nearly three months in Houston and Louisiana, a trip that he chronicled in his BU article “I Know Houston Can’t Be Heaven.” A genuine friendship developed between Bonner and Leadbitter, and Blues Unlimited readers financed a Juke Boy 45, “Yakin’ in My Plans.” Juke Boy followed up that gesture with a letter to Leadbitter in Blues Unlimited 51 stating, “I’ve sold about 100 records since they’ve been out (2 weeks). It is five o’clock in the morning and I’m writing songs (and drinkin’ beer). Put portions of this letter in the B.U.—ha ha! OK?”

This activity spurred Bonner’s career and he eventually acquired regular gigs and recording dates. Chris Strachwitz’s Arhoolie label issued two Juke Boy albums, and in 1969 Bonner visited Europe for the American Folk Blues Festival and an extensive solo tour. He also appeared at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in 1970. Releases on Liberty and Sonet followed, but, unfortunately, within a few years Bonner, part of a then dying down-home blues tradition, was back in Houston playing for low pay and booking his own gigs. Juke Boy died alone in his apartment on June 29, 1978.

In the following interview, Bonner, both honest and forthright, describes his early days on the West Coast and the difficulty of never quite catching a break. Preceding the interview are Mike Leadbitter’s heartfelt liner notes from Bonner’s Flyright album, Juke Boy Bonner: The One Man Trio.

—Mark Camarigg

Juke Boy Bonner Essay

Mike Leadbitter

Blues Unlimited #111 (Dec./Jan. 1974–1975)

Juke Boy Bonner was a friend of Blues Unlimited and maintained a close relationship with Mike Leadbitter and the magazine. Mike wrote many sleeve notes in his time, but it is arguable that his finest was for the first-ever Flyright album, Juke Boy Bonner (LP 3501). Juke Boy meant something special to Mike and he was clearly writing from the heart. As the album has been long out of print, we feel it is appropriate to reprint the sleeve note here as a reminder of Mike’s underrated literary style.

It is early evening in Houston. The sun is setting and the air is still. On the corner of Pease, just across the railway tracks from Dowling, stands the dejected-looking “Family Inn,” looking out on a vista of dusty, dirty roads and listless groups of men and women watching small, grubby children at play. Saturday night is beginning and soon more people will emerge from the tumbledown, wooden houses neighboring the inn to set out for the earnest business of drinking, loving, quarrelling, and, often, fighting. Whether their money is from work or from the welfare, it will be spent this night trying to ease away the sordid reality of ghetto life. Inside the inn the huge freezer is full of canned Jax, Schlitz, and Pearl beer. The morose houseman, S. P., and his wife sit at one of the rough tables surrounding the pool table and wait.

Darkness is creeping when Juke Boy Bonner parks his station wagon on the corner and staggers in with his electric guitar and amplifier. In spite of the intense humidity he is neatly dressed and managing to look clean and fresh. The first of the customers have arrived and the balls on the pool table are clicking gently. Friends turn to greet the resident musician and are answered with a quick smile and a grateful “yes” to the offer of a beer. He is a lean and light-skinned man with handsome regular features. His voice is quiet as he speaks to friends while settling himself in the space provided by the door. By 8 o’clock his equipment is set up and the guitar is tuned to satisfaction. It is time for him to put down his beer bottle and begin entertaining anyone who cares to listen.

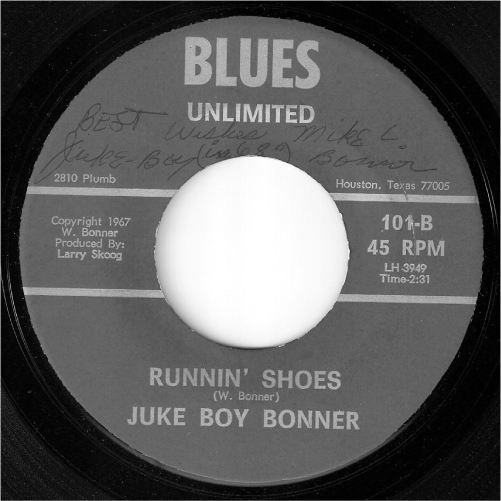

Mike Leadbitter, Juke Boy Bonner. Houston, Texas, 1967.

As the first few notes of the harmonica and guitar ring out in unison, faces begin to look up. One suddenly feels that Saturday night has now really started. People begin to speak loudly and shout for more beer, while the balls on the pool table now connect with violent cracks. Juke Boy has finished a short instrumental warm-up and, swallowing a mouthful of beer, waits for requests. It is still too early and he begins by playing numbers of his own choice. “Can’t Hardly Keep from Crying” and “Got No Place to Run” show his mood. His stomach is bothering him and signs of strain show round his eyes. His voice is full of frustration and bitterness, and the harmonica seems alive as it blends with his voice. For a moment he has lost himself, and with a grin he turns to “I Live Where the Action Is.” As the solid beat, accentuated by his stomping feet, reaches the ears, broad smiles are in evidence. “Real Quiet Fellow” follows with its Frankie Lee Sims overtones and a drunk begins a slow solo dance on the floor, carefully watching his feet as they shuffle in complex patterns.

Darkness has settled and the light from the inn calls to the crowds outside. The wire door bangs frequently and soon the bluesman is surrounded by a jostling throng. The beer is flowing freely and paper cups appear on the tables, destined to be filled from concealed wine and whiskey bottles. Despite the loud laughter and shouted conversations, Bonner’s heavily amplified equipment can still be heard with ease. More people are shuffling on the splintered wooden floor, and the pool players curse as someone collides against the table. Requests pour in. “Dust My Broom,” “Man or Mouse,” “Meet Me in the Bottom,” “You Don’t Have to Go,” “Things I Used to Do,” “Nine Below Zero.” No one calls for Juke Boy’s own songs, for they have never seen or heard his records, so he picks out the blues favorites and cleverly turns them around to suit himself. Still pleased, the askers bring over beer to help their man oil his throat and begin again.

Juke Boy Bonner poster.

As the night wears on, one wonders how many songs he knows and can play. He has sung twenty, or is it thirty by now? Perhaps it’s more, as it is now 11 o’clock. Bonner is really tired and the effects of drink are showing on the faces around him. He slows the pace and sings “Movin’ Back to the Country” to please those dissatisfied with city life; “Can’t Let Your Troubles Get You Down” to console everyone, including himself; and “Why Do You Treat Me Like You Do” for all the mistreated “lovers” who have come in alone. Suddenly a girl walks in and sits next to Juke Boy. They smile at each other, and he seems very happy to see her. He bursts into “Goin’ Crazy ’bout You” while voices shout advice and encouragement.

Midnight! Only one more hour to go. The crowd’s attitude has changed. Many are beginning to stagger home, and others argue or sit quietly looking at their beer. Will S. P. fire his pistol tonight? As you sit watching it is easy to appreciate that at this moment someone close by is being shot or cut (the usual aftermath of Houston’s big night). Juke Boy is singing “I Wonder If You Know How It Is” and follows with “Bad Breaks.” The old bitterness is rising again as he thinks of lost chances and broken promises. His thoughts turn to Europe, where his only real fans seem to be, and how he has no chance to meet them. “Blues, Blues, Blues” is the finale at 12:55. Five minutes later he wearily packs his guitar away and, with his girlfriend’s help, gets his equipment into the wagon. With a final and tired smile he leaves into the morning, knowing that tomorrow night at the same time he will have to go through it all over again. The fifteen dollars he has in his pocket is small consolation.

Mike Leadbitter

Blues Unlimited #78–79 (Dec./Jan. 1970–1971)

I have probably spent more time with Weldon than anybody else, but we had never really got down to a really good bull session until the man came to stay a few days with Simon Napier. On the 28th of October of last year, Simon brought him around to my place for the evening and after a quick session in the local pub we settled down to talk. I supplied the food and music and Weldon had the bourbon.

Blues Unlimited: How did you feel when you heard that a guy from England had your records and wanted to write your story?

Juke Boy: I thought some cat was pulling my leg, you know. I forgot all about those recordings I’d put on tape. I was just playing music, so I thought it was some kind of a crank.

BU: You’d really forgotten all those things you’d cut for Irma and Goldband?

JB: Well, I never got anything out of it. Every time I’d go through Lake Charles I’d get the same runaround, you know. I didn’t get anything but a new guitar. He’d say, “We’ve got the record working and it’ll be out next week. Just hold on.”

BU: Did it sell? I don’t think it did.

JB: Well, you got no way of knowing unless you sue somebody and that’s not good for your career.

BU: Well, Eddie [Shuler, founder of Goldband Records] did one good thing. He sent a copy of your record to us in England. Here’s a letter from Eddie saying, “Glad Juke Boy tore them up over there!”

JB: Man, that Eddie, he’s crazy. Best thing he did was put that record on Storyville. The best thing he did in his life. If he ever did a good thing, that was it!

BU: When you were with Bob Geddins over in Oakland were you paid anything for the records you made?

JB: There was, er, with Bob, if anything came of it, he’d tell you. Anyone in Oakland will tell you. If you had anything to do with Geddins and something came of it, he’d see you got your money. He wouldn’t pull nothing over your eyes. McCracklin will tell you this.

BU: Bob Geddins, he’s a person no one knows much about here.

JB: He’s with Fox now. He’s a straight shooter, though. If a record went nationwide or just went through three states, you’d know. There was Lowell Fulson, Jimmy McCracklin, quite a few fellows went to him to record.

BU: Did you know Johnny Fuller? We’ve just interviewed him.

JB: Yes. I haven’t heard from him since I left the coast in ’57. He was playing guitar, playing blues and things like “The Haunted House” and all that stuff. I don’t know what he’s done since then.

Juke Boy Bonner, Blues Unlimited 45.

BU: What made you go to the coast in ’54?

JB: Oh, well, I felt like goin’ to California. So I packed up, sold the furniture, and took off. I was married then. Me and the wife, we had two kids, we just took off with the clothes. Keep eating. I don’t want to interfere with your meal. It’s okay, I’m a slow eater. I got a small stomach. If I eat fast I get sick.

BU: You’ve got a quarter of your stomach left?

JB: About a half of it. That was ulcers. I was in Ben Taub Hospital in Houston.

BU: When was the operation?

JB: Yeah, that was ’63.

BU: What were you doing when you got to the coast?

JB: We stayed in Oakland about a week. My wife had people there. We left and went to Los Angeles for fifteen months, before we really stayed in Oakland …in L.A. I was playing on harmonica. Didn’t have a guitar at that time. I would just play around the local places; little bars, little bands, in central L.A.

BU: Was it a good scene then?

JB: It was then. I don’t know about now. Then there was good happening on the East Side. After me and my wife separated I actually got to going around the clubs and up and down the coast. Then I went sick in Oakland with pneumonia and ended up in Glendale Hospital. When I got out I had to find a job to get some kind of money.

Oh, in Los Angeles, some kind of tie shop and I just worked. I wasn’t even playing then. I was broke. One day I went home, got my harmonica, and started walking and playing. I walked from downtown, about 5th or 6th Street, and all the way up to Watts. Then about the 400 block of Central I saw the Jack in the Box club there and Mercy Dee was playing in there with a couple of old guys. A drummer and a bass. So I walked in. I had picked up a few dollars playing on the way. So I told Mercy Dee I was from Texas and he took me to his house, gave me some good advice, gave me a meal, and took up a collection for me, which was pretty good, for when I got back home I was able to pay my rent. He’s a nice fellow.

BU: What happened next?

JB: I left Los Angeles and went to Oakland, because there was a lot of money being made in canning there. I worked for Del Monte there and I’d go into town to find the musicians. Go to blues clubs where the music’s at, and, er, just anywhere you got a congregation of people swinging.

BU: How did you get to be called “Juke Boy”?

JB: Well, by two friends in Los Angeles. I used to stay with them and we’d ball around together every night. One of these guys would follow me playing guitar, as I was playing guitar and harp then, which is before I went to Oakland. I used to play that harp on the Mercy Dee Show and the Johnny Otis Talent Show. I won a prize on the Johnny Otis Show doing a Jimmy Reed number, and then Jimmy Reed popped up as a special guest and he did a Little Richard thing. That was at the Club Oasis. I didn’t have an electric guitar then. I got one of those after I went to Oakland. Anyway, these two guys, we’d go round the juke joints so damn much that they started calling me Juke Boy. I would play along with the music on the jukebox. Little Walter was popular then. I played behind him like that, and, er, Jimmy Rogers, “That’s Alright.” He was very popular in L.A. Little Walter had “Juke.” That was very big in Texas. “Mellow Down Easy” and all that stuff.

BU: Was it playing round these clubs that led you to meet Lafayette Thomas?

JB: Lafayette, oh, yes. He’s a great guitar player. He showed B. B. King how to play Lowell Fulson’s “3 O’Clock.” He took me to McCracklin and Bob Geddins to record. I was playing harp and guitar and I wasn’t used to it. The guitar was okay, I just rode along on the bass, but I couldn’t get the harp right. Lafayette told me, “Don’t worry if you miss a note, I’ll cover it up.” He played on that record.

BU: I see that on your first record you were called Juke Boy.

JB: Yes, when I left for Oakland I stayed with friends for a few weeks till I got an apartment. Baxter, their name was. They loved music. They had stuff by Redd Foxx, McCracklin, Jimmy Reed. They were crazy about music. They really started people calling me “Juke Boy,” so I just got used to using the name.

Juke Boy Bonner. London, November 1969. (Photo Bill Greensmith)

BU: When you first started on guitar, what style were you playing?

JB: T-Bone Walker. Yes, I was good at it. At that time I played T-Bone and that was all. He was hot stuff all over the States. I remember the first things he ever made. “Baby last winter, baby, the snow was on the ground.” Remember that? “You put me out, baby, and I didn’t know where to go.” That was “Got a Break Baby.”

BU: What was the first talent show you did?

JB: Trummie Cain’s, back in Houston, 1948.

BU: Man, people don’t realize how long you’ve been on the scene. They think you just started a couple of years back.

JB: Man, I’ve been there a long time. I cut some stuff for Gold Star, but it never came out, ’cause I sounded too much like Lightnin’ Hopkins at that time. I cut some stuff for old Fat Atlas on Lyons Avenue and I did some tests for Don Robey. Always the same problem, I sounded too much like Lightnin’. See, I played a lot of guys’ music—T-Bone, Muddy, Li’l Son Jackson, Smokey Hogg—I used to play all his stuff. So I was playing what was hot at the time. In the end I had to do something different, get my own style. I had to come over with something new and quit foolin’ around.

BU: Who was big when you first came to Houston?

JB: Gatemouth Brown, T-Bone Walker, Lightnin’, Charles Brown, Louis Jordan, Roy Brown. They was all great artists. Lightnin’ was real popular those days when I was coming up. You heard Brownie McGhee? That “Letter to Lightnin’ Hopkins” was a bitch in those days. Then there was Big Bill Broonzy.

BU: Do you know T. V. Slim, J. D. Edwards, Goree Carter?

JB: Goree I know. I played with him a few weeks back at Koret’s Smokehouse Lounge. Plays jazz now, he doesn’t do blues anymore. The other guys I don’t know. See, so many people just give up music. Lots of musicians die, or quit, or just dropped out. They won’t touch it again the rest of their life. So it’s hard to catch up on them, especially if you act like Hop Wilson. One bad experience ruined him. When I knew Goree, he was just a drummer.

BU: Who got to you first? Skoog? Mack McCormick? When you were “rediscovered”?

JB: Mack came by first and told me a lot of junk.

BU: Did you know that for a few months after we found you were living in Houston, no one would tell us you were found. It was Larry sent me that newspaper story in the end. Then Mack asked us not to print it, as he was saving it for a book he was writing.

JB: Well, you see, Larry was always getting those papers. He was doing a lot of writing at the time, working on the poverty program and all that stuff, so he kept up to date with the Negro newspapers. Skoog’s alright. He’s selling books now to keep his butt going. Mack came in right before him, it couldn’t have been more than a matter of months. He came by one night and wanted me to record and all that stuff. Boom, boom, boom with the hot lines, but Lightnin’ had told me about him. I haven’t seen him since. Don’t know what happened to him. Him and Lightnin’ had a big run-in about how Lightnin’ went to New York and cut two albums in one day. One for Fire and one for Candid. He got 800 dollars out of one thing, and when one company found the other had beat them on a record, they felt they had been cheated. When Mack went to Lightnin’ about the money, Lightnin’ wouldn’t have none of that bullshit. They parted ways right there.

BU: What do you think of Blues Unlimited?

JB: It’s good. I like it, I like it very well.

BU: I ask because a lot of people in the States and Canada ask us what we know about the blues as it really is.

JB: Well, there’s some people not keeping up with it, who don’t know what’s happening.

BU: But there’s people over here writing about blues and they’ve never been to America.

JB: There is? They write second-handed? But if you been to America and stayed there you understand it. You get a pretty good picture of it. You got to be broadminded about the situation. Most musicians are complicated people. They hate a lot of questions that don’t make sense. This a fact. A musician will walk off. He’s not going to hang around listening to something that doesn’t make sense. If you talk shop they like it, but you find it hard if you ask other kind of questions. A blues musician is a complicated person who got enough problems of his own without people asking crazy questions. Musicians all got one thing in common: they likes to drink. A musician’s got to be always with the people, and the people always drinking, so they drink, too. You hang around with them you got to relax and enjoy yourself. Blues Unlimited is a good magazine. It does more for the blues and people like me than anything else.

BU: Can you think of anyone else your age playing country blues in Texas?

JB: No, I can’t think of a one. Sylvester, he’s dead now.

BU: Well, I guess you’re going to follow Lightnin’ to be the last of the great Texas blues singers!