Mike Leadbitter was among the first researchers to recognize the importance of the pioneering record men and their role in the development of rhythm and blues. In an early issue of BU he urged fellow researchers to interview the company owners, A&R men, and record producers, realizing they were a long neglected resource and a potential wealth of information. Steve Tracy’s interview with Henry Glover was one of the earliest to appear in BU, and upon Mike’s assuming sole editorship, features appeared on Art Rupe, Bob Shad, and Stan Lewis that documented their beginning and involvement in the independent record business that began to flourish in the mid-1940s.

There were no course studies or existing rules on how to enter the rough-andtumble independent record business, a world populated by idiosyncratic Runyon-like characters that Ralph Bass joined in 1944. In a long career Bass worked for some of the biggest and best companies specializing in rhythm and blues: Black and White, Savoy, King/Federal, and Chess Records, producing such legendary artists as T-Bone Walker, Little Esther Phillips, Johnny Otis, Hank Ballard, the Dominoes, Little Willie Littlefield, and James Brown, to name but a few.

Whether or not by design, Ralph Bass granted few interviews. Norbert Hess interviewed him twice while Bass was working for Chess Records. The first interview, conducted in 1973, focused on his involvement with Johnny Otis and Little Esther. Speaking with complete candor on the genesis of Little Esther’s “Double Crossing Blues,” he offers us a rare and humorous perspective on discovering and recording a new talent and the hazards he encountered promoting a hit record. A second interview two years later covered the broader aspects of his fascinating career.

In later years Ralph Bass hinted at the possibility of a biography, but that project never materialized. Thankfully we have Norbert Hess’s compelling interview. Ralph Bass died on March 5, 1997.

—Bill Greensmith

I Didn’t Give a Damn if Whites Bought It! Ralph Bass Interview

Norbert Hess

Blues Unlimited #119 (May-June 1976)

I have visited and interviewed Ralph Bass twice in his office at the Chess Building in Chicago, 320 East 21st Street. The first time, unfortunately, my tape recorder broke during the interview without my notice, and the second time, Ralph was involved with visitors and recording and was not concentrating too much on my researching questions. By the time you read this, I am again in the States and I hope to get more information from this interesting man. When I set up a date with Ralph in September 1973, I mentioned I’d be mostly interested in Ralph’s connection with Johnny Otis, Little Esther, and both Savoy and Federal Records. When I arrived at his office on the fifth floor of the Chess Building, I first asked him how he became interested in music at all. I was so impressed by his enthusiastic impromptu story that I just let him tell it.

No, I’d rather not do that, I’d rather just stick to Johnny. (laughs) I’ll preface it by a short thing about Johnny (Otis). I was a producer of nothing but jazz. I was recording Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker and Wardell Gray and Dexter Gordon and all the jazz greats. Erroll Garner, I did all the early hits for Erroll Garner. I was such a jazz fanatic that if I heard a commercial record I would break it. One day, by accident, I recorded one of the biggest pop hits of the country, “Open the Door, Richard,” and I said, “Is this [the] kind of shit that makes money?” Because I was spending all this man’s money on all this jazz shit and it wasn’t selling. So then I got very interested in R&B. We called it “race music” then, and I’d heard of Johnny. Johnny used to have a band that used to play at the Club Alabam in L.A. on Central Avenue. So I contacted him, how and when I just don’t remember. I know he had a club with Bardu Ali, who is now Redd Foxx’s manager, place called the Barrelhouse out in Watts. I signed Johnny to a contract, doing commercial things. There was a group called the Robins and which I had signed to the company I was working for, Savoy Records. I was A&R man for Savoy and we had brought … there was a little girl, Little Esther, Esther Phillips now. She was thirteen years old and I remember Johnny and I were in the midst of recording the Robins at a studio in L.A. called Radio Recorder, and Esther came down and Johnny said, “Let’s audition her.” And I said, “Okay,” and at the end of the session I took part of the group and I used the bass voice in the group, Bobby Nunn. And just fuckin’ around we did one thing by Jesse Mae Robinson called “Double Crossing Blues.” Johnny had reworked the song, he had an act at the club, comedian act, they did a thing about the “lady bear,” which was very funny. I didn’t understand it at first, being strictly au fait, well, jazz au fait. I’d never heard the expression about “lady bear,” and I used to go in the club and say, “What the fuck are you laughing about?” every time they get about the “lady bear” till Johnny told me what “lady bear” was. “A ‘lady bear’ is an ugly, black broad, who can’t get a man because she’s so ugly. She’ll hit you on top of the head and drag you away (laughs), very aggressive.” He used the gimmick line in the song and changed the lyric. He gave the song to Esther and we recorded with Bobby. Herman Lubinsky, who was a nasty motherfucker—he’s a good record man, a great record man, but he’s a cheap motherfucker, that’s why he’s a millionaire, I guess. I sent the dubs to Herman Lubinsky in Newark and I said, “Send me $10 for the girl who didn’t go to school, pay her bus fare,” and all that shit. He wrote me and said, “What the hell are you runnin’ out there, an office for schoolchildren? I don’t pay no damn guy $10 to hear a little thirteen-year-old kid sing!” Well, of course, in those days thirteen-year-old kids were unheard of. Especially Esther, who never sounded like a thirteen-year-old kid. There was another girl at that time who was very popular, but she had a childish approach to a song. I just sent the dub on, no title, no information, no nothing. We were hoping that one of the things that Johnny had done with the Robins was gonna be a hit. Anyway, about four o’clock in the morning I get a call from Newark, New Jersey, from Herman Lubinsky. “Who’s that little girl you recorded and sent me?” he said. “She’s gonna be the biggest thing in the country, sign her, get her to sign contracts now,” I said. “What in the hell are you talkin’ about, man?” Then he told me a story about the disc jockey Bill Cook in Newark.

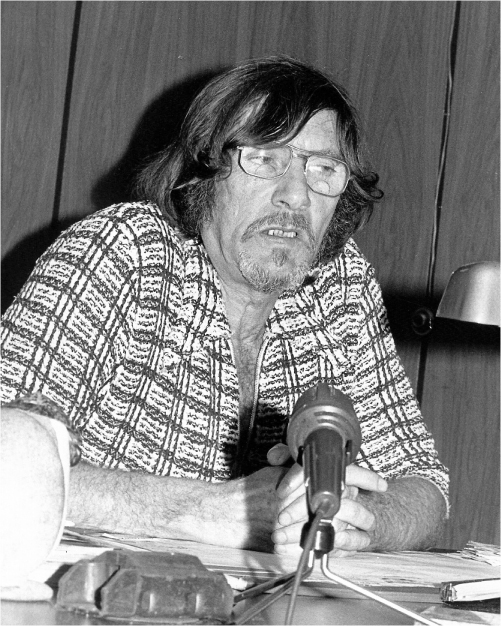

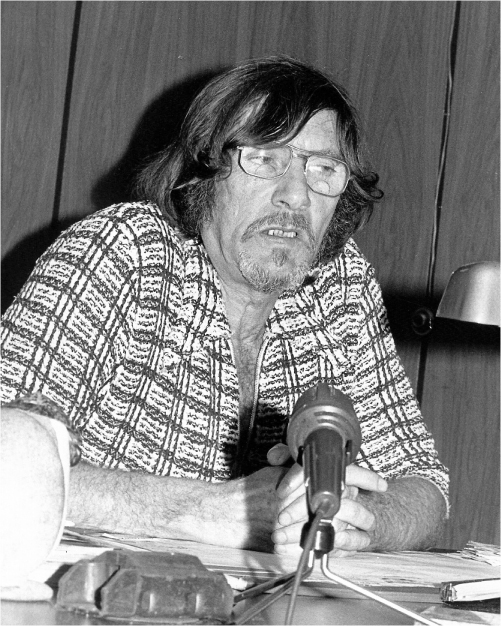

Ralph Bass. PS Recording Studios, Chicago, 1977. (Photo Norbert Hess)

There was a disc jockey who came into Herman’s office—he had a big show. In fact, Bill was Roy Hamilton’s manager later on in life and Bill was the biggest thing in Newark. Bill came into Herman’s office and said, “Herman, there ain’t a damn thing that’s sellin’, nothing big. Do you have anything new that I can listen to? Maybe you got something that might mean something?” Herman said, “Well, my California man sent me some shit, just a pile of shit.” So he listened to the things and all of a sudden he come running back, very excited, in Herman’s office. He said, “Man, who is this? Goddamn, this is great, what’s the name of this thing? This thing is going to be a smash hit!” Herman got all excited and Bill said, “I’m gonna put it on the air. What’s the name of the thing?” Herman said, “I don’t know. We didn’t put any title on it, just that dubbing.” He put it on the air and, sure enough, the board lit up. And he had a contest. Herman couldn’t wait for me to tell him what the title was. He had a contest and he said “Double Crossing Blues.” That’s a funny thing, because everybody got double-crossed on this record.

After the phone call I drove my car, must have been four o’clock in the morning. Johnny lived out in Watts, knocked on the door. Phyllis, his wife, got up and I said, “Get Johnny up, Phyllis!” Johnny had just gone to bed after playing at the Barrelhouse. I said, “Wake up Johnny, we got a smash hit!” He said, “Man, I heard that shit before.” (laughs) I said, “No, man, we got a smash hit!” He said, “What, the thing with the Robins?” I said, “No, man, the thing with Esther!” (laughs) He said, “You got to be kidding, that piece of shit?” He got the dub out and put it on the record player, shaking his head. He couldn’t believe it. He said, “Of all the goddamn things I’ve ever done in my life, this piece of shit has to be it!” I said, “Well, Johnny, now, we both know that the things we dig ourselves never necessarily mean that the public out there will dig ’em. It’s just whatever is a combination of lyric. Esther, she sounds so much like Dinah Washington.” Her mama was a domestic, worked out in Pasadena. We got in the car. I had some contracts with me. We went out to where her mama worked and had her sign the contracts.

What happened, we now had a smash record and Johnny knew, being a musician, that any success he would have would be through Little Esther. Who the hell wants to hear a goddamn drummer—what the hell does it mean? But Esther, he managed Esther. First of all, we didn’t have no money. I didn’t have no money, Johnny didn’t have no money. We know we had to get some bread and front [money] to get a bus to go on tour. We went to a man named Harold Oxley, who had a booking office on the West Coast. There were very few booking offices that booked nothing but soul talent, black talent. So Harold started booking us, but we needed money for a bus. I said, “Johnny, what we’ll do is make enough money on these dates on the West Coast to be able to get us a bus.” There was a cat named Ed Fishman, who was managing the Robins. The Robins were the group. We used their bass voice, Bobby Nunn, to sing with Esther “Double Crossing Blues.” Johnny said, “This motherfucker, Ed Fishman, is a thief and a crook. He’s gonna fuck us out, fuck us up!” I said, “No, we’ll be careful.” So, sure enough, Ed Fishman wanted to stop the record, because he said it was the Robins’ record, not Esther’s record, because Bobby was on it. So I said, “I’ll tell you what. We’ll give you part of the thing. We’ll give you Esther, but we need some time.” We were gonna fuck Ed Fishman, but we couldn’t do it now. We had to play these dates to get enough money. Well, he gave us a release saying the Robins don’t claim the record, which meant that Johnny could make enough bread off the record to be able to do what he wanted to do. When Ed Fishman found out we double-crossed him and signed Esther to Harold Oxley, he dedicated to fuck us up.

I never will forget, we had to play three one-nighters, one in Bakersfield and one in Redwood City, and then we had to play the big dates, Oakland and San Francisco. I went up ahead to promote the record—it was unbelievable how big this record was. There was a promoter there—he and his wife were the promoter—I can’t think of their name. I laid the promotion out in front. There was a cat named Jumpin’ George Oxford, a white boy who had the only soul program in that area, and I had made arrangements for her [Esther] to be in this show. He had a very great friend of his who was a great basketball player who had a show in Oakland, Don Barksdale. I also had a personal appearance for Esther set up with the biggest record shop in San Francisco. Anyway, I get a phone call the day before the one-nighter in San Francisco from the local promoter in San Francisco, saying, “How old is Esther?” I said, “She’s thirteen.” He said, “I got a call from the police department saying because of her age she couldn’t perform. She can’t perform in a place where booze is served.” California had a real rough law about minors because of the Jackie Coogan thing, where Jackie Coogan’s mama fucked him out of a lot of money and because of a lot of child actors, minor actors in California, making a lot of money, so they had these laws. I said, “Good God almighty, Ed Fishman probably called the police department and said, ‘Hey, you know there’s gonna be a thirteen-year-old girl gonna appear on a show where booze is gonna be dispensed,” and all that bullshit. I remember walking the fuckin’ streets at night trying to figure out a way. I couldn’t get hold of Johnny, he was performing, en route … where the hell was Johnny? Then an idea came to me. I got on the phone. There was a girl named Mickey Champion who sounded a little bit like Dinah, but who could imitate any singer you could think of. I got hold of Mickey and told her, “Call Oxley, Johnny’s booking agent, and he’ll give you the bread. Get a plane and come right up here, I’ll meet you.” Johnny didn’t know anything was happening, ’cause I couldn’t reach him. I was gonna have Mickey be Esther. I was gonna substitute her.

Meanwhile, I had to cover myself up, so I called the promoter and said, “Who are the police authorities?” He said, “The Juvenile Department.” I said, “I’d like to meet with them, give me their number and their names and we’ll meet.” I met with them the next afternoon and they read the riot act to me about minors performing. I tried to give them a sob story. “This little girl had no money and this is her big break,” and all that shit, and that wouldn’t work. Finally, an idea came to me. I said, “How does the law read? Will you read me the exact law?” They said, “No one under eighteen could perform while intoxicating beverages were dispensed with.” I said, “Beautiful, I’ll tell ’em to just close up the fucking bar while she’s singing.” (laughs) Only says “while alcoholic beverages were being dispensed with,” that was the loophole! They said, “Okay, but she can only sing till ten o’clock, because that’s the law.” I said, “Okay.” Well, Mickey came up and Johnny came in about the same time. I told Johnny the whole story, and Johnny said, “Oh, shit, that’ll fuck us all up!” I said, “No, Johnny!” and I told him what the plan was. We got Esther in her room and her sister, who had been traveling with her. I told her, “You got to get yourself back to L.A., ’cause you can’t be seen here.” I told her what we were going to do and she started to cry. I said, “No, baby, don’t worry about a thing, this is only in California. Unless we get over these two goddamn dates we got up here, which will buy us the bus to be able to perform all the one-nighters we got, we won’t be able to work.” So we put a veil on her to cover her face up and got her ass out. (laughs) We took her to the bus station and sent her ass on to L.A. Meanwhile, one of the cats we had hired to take Bobby’s place to sing the male part to “Double Crossing Blues.” Mel Walker, his name was. We got a record player and we got the two of them in a room and we got them rehearsing all fuckin’ night “Double Crossing Blues,” so that Mickey sounded exactly like Esther. And we got the fuckin’ short dresses—Mickey was, like, twenty-one, she had two children and we put the fucking short dress on her all night long, that’s what she did.

Next day we had a deejay thing with Jumpin’ George in Oakland. (chuckling) Johnny and I were cueing Mickey in on Esther’s life in case whatever questions are asked. I said, “Look, baby, if you can’t answer the questions, you must keep your mouth shut and I’ll answer it for you or Johnny will answer it.” So the three of us went down there, Johnny like this (pantomimes and laughs)—he’s scared to death. He ain’t never done no shit like this. We got to the station and the deejay is asking all these questions. “How does it feel for a young girl?” and that bullshit. Every time he’d ask her a question that she couldn’t answer, Johnny or I would bust in and answer the question and we got over that hurdle. Now, the next was a personal appearance at this record shop. God damn, we got a block and a half away and there were the police. Shit, the arrest squad! There must have been five thousand kids there with their mamas, all there to see Esther. Johnny said, (laughs) “I ain’t goin’ through there, we gonna get killed. We got to get killed, you can’t fool those kids.” (breaks up for a moment) I said, “Johnny, it’s either now or never, baby. Either we get through this or we’re dead.” We finally plowed through this crowd and it was just a small record shop and you could hear the voices sayin’, “Hey, where’s Esther?” “Shit, if that’s Esther, my mama is my grandma.” We could hear this rumble, “Where’s Esther?” We were back in this booth and there was a wall, and we thought for sure these people were gonna take this wall in on us. So I finally got an idea to quiet them, because we knew damn well there was gonna be a riot. I said, “Have you got a record player and a microphone?” “Play the fuckin’ record,” and I says to Walker, “You and Mickey get up there and sing this fucking song, sing it here!” They played the record and then Walker and Mickey started singing the damn thing and the kids said, “Well, maybe it don’t look like Esther, but she got to be. Sounds just like her, got to be her.” We passed that motherfucking test. (laughs) Poor Johnny was almost in a state of shock. He was scared to death some shit was gonna happen.

Johnny Otis.

Now, something happened with one of the trumpet players, Lee Graves. He decided he was gonna go home because he didn’t dig what was happenin’, or something was going on. So I’m down [at] the bus station looking for him, bring his ass back. You must remember that Johnny’s band was the first entertaining band. He decided the band wasn’t just going to sit down and play or stand up and play. They were going to perform, and he had an act, all kinds of things goin’—he had a gimmick. You must remember that Johnny had played the Apollo Theater. He’d seen Pigmeat Markham work and Moms Mabley work, the great black comedy acts work, and he had incorporated a lot of this shit in the band, so that they did skits. Some of the skits Pigmeat did and so forth, whatever he’d seen. The cats in the band sang, they all moved. It was the first entertaining band in the country. In fact, James Brown copied all his shit from Johnny’s band, because Ben Bard—later on, not too soon after that—Ben Bard booked Johnny’s band. I had to get Johnny away from Harold Oxley for reasons, other reasons. Later on I gave James Brown to Ben Bard and Ben became the manager—that’s another long story. When James formed his band remembering Johnny’s band, I had James do the same damn thing with his shit. A very entertaining band, everybody had to do something—okay, now getting back to the story. So I went to get Graves, who had an integral part in many of the things that Johnny was featuring in the band. By the time I got back to the hall it was after ten o’clock and here’s the promoter, man, was he worried. He said, “God damn, they’re gonna put us all in jail, shit!” It was after ten o’clock and they didn’t close the bar down while Mickey was singing. Johnny wasn’t there. I said, “Where’s the man?” They said, “There he is!” Here comes the lieutenant, same cat I’d talked to. I had a special license he’d given me to perform providing the bars were closed and she didn’t sing after ten o’clock. You know, what the fuck, ain’t nobody get to a dance till after ten o’clock! I said, “Come here, I want to talk to you ‘real quiet’ … the girl up there singing is not Little Esther. That girl up there is over twenty-one. I decided not to play Esther, because most of these people come here after ten o’clock at night.” You must remember it was more of an adult crowd than the type of audience that goes to see a show today. I said, “So I pulled her understudy in, but if anybody ever finds out that little girl is not Little Esther, there’ll be a riot here!” And the place was jam-packed. There were wall-to-wall people and they had a police broad searchin’ all the women coming up for weapons and they had a policeman searching all the cats. “There’ll be a riot here. You’ll need the whole damn police force to put this fuckin’ riot down. If you want to go backstage and be very quiet about it, Mickey will prove her name is Mickey Champion and she’s over twenty-one. She’s got her driver’s license and the whole bit, okay?” I wasn’t gonna take a chance putting this little girl on, you know. I sent her home. That was the truth. He went back there and satisfied himself that it wasn’t Little Esther; it was Mickey Champion. Johnny was sweating! (breaks up for a moment)

Little Esther Phillips.

Everything was cool. My only thing was if there was anybody in that audience who was from L.A. and knew Little Esther, ’cause Esther had worked all around Watts. She made all these amateur shows. She’d been doing some work around there because of the popularity of the record at that time. I was just hoping that nobody knew her. Well, sure enough, about twelve o’clock here come two dudes: “Hey, baby, you the manager? Where’s Little Esther?” I said, “Man, what are you talkin’ about?” He said, “Where’s Little Esther? That broad up there ain’t Little Esther. We are from L.A., we know who Little Esther is!” I said, “Come here, baby, she was here.” I was hoping he wasn’t here at ten o’clock. I said, “She was here,” and I took out the special license, the one from the police department that let Esther sing till ten o’clock. “See,” and I showed him the fucking license. I said, “Man, we don’t want her to go to jail, she’s only thirteen. Be cool about it!” I talked ’em out of the damn shit, give ’em a few bucks. (laughs) Everything was beautiful except getting the fuck out.

As I was paying the damn hotel bill—George Washington Hotel, I think, some black hotel in San Francisco. As I was checkin’ out, in came a phone call for me, said, “This is the San Francisco Chronicle. We were just told you pulled the biggest hoax in show business.” I said, “What’s this?” They said, “You had a little girl you were advertising as Little Esther and she didn’t appear.” I said, “If you print one line about that fuckin’ story, we’ll sue you for everything you got! That was Little Esther up there last night! We’ll sue the shit out of you!” “Man,” I said, “Johnny, let’s get the fuck out of here before everybody finds out what’s happening.” I said, “Let’s go and see Don Barksdale,” the basketball player, who had a show, was a big man in the Bay Area and went to school with Johnny. We drove to his house and told him the whole story. He said, “You mean you lied to me, your buddy?” “We had to!” He said, “Don’t worry about it. I’ll cool the newspaper.”

I tell you this story about Johnny’s early career. If we hadn’t done that, God knows how the fuck we’d have made all these—we didn’t have no money—where we’d have got the bread to get the bus, to make it possible for everything that happened to Johnny. There are many other stories connected with Johnny and what we had to do. I think Johnny’s biggest thing was in being able to handle people. He has a kind of a charisma about him that attracts people to him and they believe him. When they leave him they’ll curse the shit out of him. They’ll think he’s stealing the ass off them. I don’t think Johnny ever did that, knowingly. They’ll talk about him like a dog behind his back and they’ll blame everybody else, including me, for what happened, but when they get with Johnny they love him. There’s a thing about Johnny. He’s a natural leader-type thing. He has everybody believing in him while they are with him, but when they’re away from him, something else. But with him, very loyal. He has tremendous talent, because he went through a lot of shit.

We both went through a similar lot of shit. He married a black woman, I married a black woman. Johnny was married to a black woman way before I was, and so for all purpose and intent I think Johnny was black. Nobody knew Johnny as a white boy. Johnny was Greek.

The other story about Johnny being white and being in black music was … we played Biloxi, Mississippi, a one-nighter, and I had Little Esther in New Orleans. It was during Lent period. In Lent period you don’t play in New Orleans, nothing happens in that period. I was in New Orleans and we were taping a show we had to do at the auditorium, a one-nighter we had to do, and we were taping a show with one of the deejays down there. In getting Esther back to Biloxi we were late getting there. I got to the club—no club, it was shit. There were all these warehouses that were boarded up with wooden windows.

The promoter came on out and says, “Hey, is Johnny Otis white or black?” I said, “Who want to know?” He said, “The police, man, we all goin’ to jail.” In the South a white musician couldn’t play with the blacks. There was a city ordinance about that kind of shit. I said, “Tell them to come over, I’ll talk to them.” “We all goin’ to jail,” he said. Poor Johnny, man. I look at the bandstand, everybody’s looking over to see what’s gonna happen, ’cause down there they put your ass in jail for … Here come the police with his nightstick. He be hittin’ his leg with the nightstick and a toothpick in his mouth. He ready to hit somebody. He said, “What are you doin’ down here, who are you?” I said, “Is it against the law to protect my money? I own this band, I’m down here protectin’ my money.” “Well, what’s that white boy doing up on the bandstand?” he says. I said, “What white boy? I don’t see no white boy!” I’m trying to think what to tell this fuckin’ cat. “I don’t see no white boy!” He said, “You’re from the North. Down here we can always tell these niggers …” and he started telling me all this shit about how they can tell niggers and he got to some fingernail bullshit. I ain’t never heard of no bullshit they can tell by fingernails. While he was talking an idea came to me. I said, “Wait a minute, man. You want to give that dark boy a whole lot of credit?” He said, “For what?” I said, “Well, his great gran’mama is black and he ain’t ashamed of being black. Just suppose someone like that came down to your hometown, eat in your restaurant, stayed in your best hotels, then I hit him on top of the head and married your women.” “Shit!” he said. “He don’t want to do that, he’s black, his great grandmammy black, he’s black!” So the police took the hat off his head and scratched his head and said, “Come to think of it, there must be two, three millions down here just like that, passin’!” (breaks up for a moment)

The sequel to the story is that now he thinks Johnny is black, dig? ’Cause we used to put dark makeup powder on Johnny and dye his hair real black. The sequel to this story is, after this tour, I had to get back to my gig with Savoy Records. ’Cause when Johnny asked me to come with him, he said, “I can’t trust nobody. Ralph, would you come and manage my band? Take care of the bread and everything. I was on that road for four months. I lost all this weight, man.” (laughs) I had to get back to my gig, so I said, “Who you want to take care of the band?” He says, “Earle Warren.” Earle Warren was the straw boss for Basie, played alto sax for Basie, and Johnny and Earle were very tight. I said, “Okay.” Now, Earle could “pass.” He looked like a Mexican.

Meeting Ralph again in April 1975, I heard a big part of the rest of his career: Born Ralph Basso on May 1, 1911, in New York City to a German mother and an Italian father, Ralph learned to play violin in school but soon became interested in jazz records. By 1944, an accident to his hand ended his career as a musician and he became a disc jockey and lecturer with a growing interest in race music. He noticed that the black market wanted records that the major companies were not supplying. Ralph, who was already in Los Angeles, started to produce some race records himself and sent acetates to several independent companies offering his services. Only Black & White of Cleveland, Ohio, answered, and Paul Reiner, head of the company, asked him to arrange further sessions. Here, I have to quote briefly from an early BU (#79, page 10):

Ralph went to the local Musicians Union on Central Avenue to find out who were the best musicians. He was told to contact Sammy Franklin, then popular in the clubs. He signed Franklin and went to Radio Recorders, then the only independent studio in L.A., but they were booked up, so he hired a studio in a radio station. He had half an hour before Reiner arrived, so he explained to the engineer that he hadn’t the faintest idea about cutting records and asked for a quick briefing. Then he rumpled his hair, rolled up his shirt-sleeves and generally “mussed” himself up. As Reiner walked in, Ralph was rushing around and shouting instructions with great authority. Impressed, Reiner soon left, telling an aide, “the guy looks like he knows what he’s doing.” This is how Ralph became a producer.

That was in 1944. I started for that company. I produced T-Bone Walker. “Bobby Sox Baby” was a smash hit, Lena Horne, Phil Moore, a lot of jazz acts. Earl Spencer, the big band Stan Kenton bought the book from. Some square bands, like Henry King, Jan Garber, society bands. A great Mexican named Chino Ortez sold big to the Mexicans. I was the first one to record Essy Morales, the great flute player, who died many years ago. Also Ivie Anderson. Jack McVea—“Open the Door, Richard!”, the first million-seller I produced. It was the one that changed me. I was recording all this heavy jazz shit in L.A., including Charlie Mingus. I did “Bird” (Charlie Parker) and “Diz” (Dizzy Gillespie) with Slim Gaillard and it wouldn’t sell. Then I was doing a blues date on Raymond Tarren, McVea’s drummer. We were doin’ eight sides to fulfill a contract and they all sounded alike. I said, “Let’s do something different!” and we came up with “Open the Door, Richard!” It changed my whole concept. Been on a commercial kick, I’ve done some jazz things since, but only commercial jazz. Sammy Franklin was the first band I ever recorded, “The Honeydripper.” I copied Joe Liggins. Portrait was my own label, with Erroll Garner on it. My own company—that was during Savoy. I had a label called Bop (before Savoy). I had the original “Chase” with Wardell Gray and Dexter Gordon, recorded live. I knew I had the first jazz hit on my hands, but I didn’t have money to finance the pressing. I was in Chicago seeing my distributor, Monroe Passis, who was originally a branch manager for King Records in Chicago, but opened up his own distributing company. While I was in his office, Herman Lubinsky called up because Monroe was handling Savoy. Lubinsky offered to help when he heard my needs. I went to New York, as I was going to do a deal with Al Green to handle “The Chase.” Al was an alcoholic and had gone missing and nobody could find him. As my money ran low I called Herman Lubinsky in desperation and that’s when we made a deal. I talked to Freddy Mendelsohn, who’s running Savoy now, and they are gonna rerelease those things I did on that label. Herman suggested I go on a salary and be his man on the West Coast, and that’s how I got with Savoy. That was 1948. I stayed three years until 1951.

By now Savoy has been bought by Arista Records of New York, but there are plans to reissue several albums and 78s later this year, among them Brownie McGhee, Johnny Otis, Little Esther, and several other blues, jazz, and gospel acts. In 1948 Ralph tried another deal with Al Green as he looked for a distributor for his Erroll Garner recordings, to be issued on his Bop label. Again he contacted Lubinsky, who agreed to do the Bop/Garner distribution, but he double-crossed Ralph and issued them on Savoy. Lubinsky did cut four sides by Garner. When Garner got to the studio he found the elevator broken down and had to walk up twenty flights. When he arrived exhausted, Lubinsky wanted him to play boogie-woogie! Garner refused and cut “Laura,” “Penthouse Serenade,” plus two others. He vowed never to cut for Lubinsky again. All the sides Ralph cut with Garner were “one take” items, cut on three-minute shellac discs. On each take, after two and a half minutes, Ralph would signal Garner he had thirty seconds to wind it up.

Ralph was the West Coast A&R man for Savoy and spent only a little time in New York, where he recorded Lucky Thompson, Linda Hopkins, and Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry for the company. He was responsible for almost all of the Robins’, Johnny Otis’s, and Little Esther’s records. He met Otis at his Barrelhouse in Watts.

The Barrelhouse, a hundred people, with a dance floor in the middle, the bar … Bardu Ali and his wife, Tila, used to be in charge of the thing. Johnny’s only thing was the goddamn band—that was his part of the thing. Johnny hired the acts and played the music there. There was a place right next to the Barrelhouse, and that’s where Johnny got all his fuckin’ ideas. It was a storefront church. At intermission time Johnny and I would go out and stand in front of this old storefront church and steal all the fucking tunes played inside! (breaks up for a moment) That’s true! That’s where Johnny got a lot of his ideas, from the old storefront church. The Barrelhouse was a local club, most of the people who went to the Barrelhouse were from that area—it didn’t draw any Hollywood figures. Nobody would “slum” out there, it was too rough. I remember bringing Herman Lubinsky into the club. Herman, I don’t know why little cats always like carrying a lot of money on ’em, I don’t know why. There’s something about small cats, short cats with power, I don’t dig. I think it’s because of the fact that they know they’ve been very short as a child and they want to get even with the world. Like all them motherfuckin’ dictators we’ve ever had, everybody in life that was a bad guy, was always a short cat. (laughs) It’s a remarkable thing. Lubinsky was short and fat, puffing on a cigar, had them diamonds on his hands, and always carried a couple of thousand dollars in his pocket. When we got finished he went to pay the bill in the Barrelhouse and he flashed all that fucking money—shit! Johnny came over and said, “Johnny, get us out of here, man!” Johnny had to get two or three cats to get us out of the club. (laughs) It wasn’t a bad place, but you don’t flash money like that in a ghetto club. The Barrelhouse was a ghetto club. Johnny had a lot of good talent that performed there, local talent, of course, no “names”—he couldn’t afford “names.” Esther never sang there. She couldn’t work in a club in California, she was only thirteen. I think they sneaked her in a couple of times. There wasn’t much you could really say about the Barrelhouse except that was where Johnny got all his ideas from first and worked his thing up, the blues thing, the blues kick—got his band together.

After the Robins left and later split into the Robins and the Coasters, three members of the band took over the vocal group part as the Blue Notes (Lee Graves, Donald Johnson, Walter Henry). Ninety percent of the Savoys were recorded at Radio Recorders. Esther’s Federal sides were done in Cincinnati. I think there were only two independent studios in Los Angeles at the time. There was one studio on Western Boulevard, but they were crazy. They wanted royalties on every record, on top of paying them for the use of the studio. I told them, “Kiss my ass!” (laughs) So we were all using Radio Recorders. Capitol was using Radio Recorders, too. It made it difficult for studio time. You had to book it two or three weeks in advance, minimum.

On some of the Savoy discs Bass is credited as co-author of the songs.

Yes, Johnny and I would write half the night, when we had the time. We’d be in the streets of Los Angeles, two or three o’clock in the morning, shooting ideas at each other. I was a gimmick writer, the gimmick line, that was my forte. I could think of the gimmick line, that was the whole song, the basic idea. “Work with Me, Annie” was my gimmick, but my name is not even on the song (credited). A lot of times I didn’t put my name on things, as I figured I already had the publishing rights. Later on in life I learned. I believe if a cat makes a genuine contribution to a song, he should be listed as one of the writers.

Ralph also traveled for a while with the Johnny Otis caravan.

Just the first four months; after that I went back to my gig. I became an “instant road manager,” because Johnny couldn’t find anybody he could trust. I became a pretty good road manager. (laughs) While the band would be playing a gig, I’d be working on the bus, trying to put it together, but we never missed a gig, outside of one time—they made the gig, but without instruments or Esther. Redd Lyte was driving the panel truck and put it into a full spin and turned it over several times. We had instruments all over the place. I buried Mario Delagarde’s bass fiddle there. Redd Lyte was arrested because he couldn’t find his driver’s license, as he’d lost his wallet when the truck was turning over. Lee Graves, Esther, and Redd Lyte were in our group, so they missed the gig. The rest of them played it. Mel Walker and Johnny probably sang the whole thing. (laughs) We showed up a day or two later; we had to jump from Shreveport to Oklahoma City. That’s how we were booked—one-nighters, four or five hundred miles apart, with no sleep. Half the time we never stayed there, just kept driving, tryin’ to make our gig, sleep in the car. No bed of roses. Actually, it was illegal to jump more than two hundred miles a day. The band, they was all nice cats, we didn’t have any problems. Some problems with Lee Graves, that’s about the only one we’d have a problem with. Lee would get high on the bus. I remember one night goin’ through Oklahoma, Lee and the valet got high on the bus. I didn’t give a damn, personally, but in the Deep South they were rough if they caught you with the shit. You got five, ten years in jail, then they’d confiscate the damn bus. I made a rule that nobody would smoke the shit in the bus. I knew they were smokin’ the shit, so I stopped the bus and put ’em off, took their shit, and left them in the middle of the highway. It was dark. We got their luggage out and said, “Go home, you cats, fuck it!” We hadn’t intended to leave them, just scare the shit out of them. We drove about a mile down the road and pulled over and waited. Then I said, “Okay, let’s go back and pick ’em up. I think that’ll teach them a lesson!” (laughs) There was very few problems after that. Some rules I laid down for the good of all of us, not for one or two. We had to think of survival, and in the fifties, survival was the name of the game.

Later, Earle Warren, Preston Love, and “Papa” Hess traveled with the band as road managers, respectively. In 1951 Ralph Bass moved from Savoy to King Records.

Federal was owned by Syd Nathan, head of King. It was a subsidiary created for me. All my productions went on to the Federal label. Esther was signed under contract to Savoy, and when I went with King I knew that the contract was no good, because here in California you had the Jackie Coogan law. The contract had to be approved, number one, by the courts, and the court would have to set up a guardian for her. Her Savoy contract was never handled that way. It was just a contract signed by her and then by her mama, which was not legal in the state of California and I knew it.

That’s how I got her to King. I went to California and we hired an attorney, who did it properly. Went through the courts and the contract was declared null and void, and she went with me to King. Johnny never came with me to King or Federal. Syd gave me that label, Federal, because I had a production deal with him. To keep it straight, every record that came out on Federal, I got a production credit for. All my acts were on Federal, which was even James Brown later on. Johnny never came with me. He got fucked up with Don Robey down at Peacock, and he gave him all that black-white shit down there and Johnny double-crossed me, really, instead of signing with me. He was supposed to sign with me; he signed with little Don Robey. Robey gave him a big story and then he got fucked out of that big song they did with Big Mama Thornton, “Hound Dog.” Johnny never was with King or Federal. He played behind Esther on all the things I did with Esther. We never did get a hit with Esther again, not a smash hit.

Little Esther recorded thirty-two titles for Federal in the period from January 1951 to March 1953. In fact, all of these were produced by Ralph, but the last four songs were not backed by members of the Johnny Otis Orchestra. On most of the others the entire Otis group, without the leader, played the tunes and they were released as “Little Esther with Orchestra,” or under the pseudonym of Earle Warren. The Dominoes dueled with Esther on two numbers before they became stars under their own name. Bass combined Esther also with Little Willie Littlefield and Bobby Nunn on several other songs.

Just a chance thing, nothing pre-planned. They just happened to be in town. Leiber and Stoller wrote some of the songs for Esther, like “The Storm” and “Saturday Night Daddy.” “The Storm,” they wrote it on the date in the studio. We were having trouble getting a sound effect of rain, so I put the mike in the urinal and flushed it and got a giant sound like rain. That was one of the most famous stories that went around King Records, how I got that sound effect.

Ralph produced an endless list of rhythm-and-blues artists for Federal, like the Dominoes, the Midnighters, Hank Ballard, Smokey Hogg, Preston Love, Hemy Hill, John Lee, Roy Byrd, Dorothy Ellis, the Royales, Pete Lewis, Jimmy Nolen, Jimmy Witherspoon, Big Jay McNeely, Little Willie Littlefield, Young John Watson (nowadays Johnny “Guitar” Watson), and others, with such hits as “K. C. Loving,” “So Fine,” “Every Beat of My Heart”—well, there are so many. Johnny’s band was used on many as the house band.

Most of the others don’t stand out in my mind, ’cause nothing ever happened to them. You only remember the ones that are important to you. I recorded thousands of sides I don’t even remember.

I asked Ralph if he had any problems with censorship on such catchy lyrics as “Work with Me, Annie,” “60 Minute Man,” or “Saturday Night Daddy” (by a then fifteen-year-old Little Esther).

The first censorship record came along with “Annie.” “60 Minute Man” was the next thing jocks wouldn’t play. [Actually, “60 Minute Man” came first.] “Annie” was the first one that little kids started buying and bringing home. We never made that record for kids, but for adults, black adults. The funny thing about whites, if they talk about sex in their own language, it’s cute—like that famous song “Makin’ Whoopee” that Eddie Cantor did. It was a great song, but what the hell was he talkin’ about? He was fuckin’ the broad and they had a baby and that was from “Makin’ Whoopee.” That’s cute. But as soon as you say something that the white doesn’t understand, like “Work with Me, Annie,” there’s tremendous sex connotations. Actually, those days we used the word “work” for everything by musicians, people in the show business—“Work with it!” relating to a dance routine or a great solo. It was a general word, it didn’t just mean sex. We used it in the song as an adult humorous word. It was funny, but it was called to our attention, it was a dirty expression, it should be banned. That was not a “kiss of death” for the record (laughs), it was a boon. We sold close to a million on that and “60 Minute Man.” Those things we did then are tame compared to words used today. I wasn’t aiming at a teenage market, just a general market, kids from eighteen and up. We didn’t have no twelve-, thirteen-year-old kids listening to our records, and of course, the blues were done for black adults. We didn’t even have whites in mind. I didn’t give a damn if whites bought it—if they did, groovy!

Ralph has many stories to tell, for example, about the Dominoes.

I was in New York and I was running the New York office with Henry Glover. Syd Nathan owned that building. On the top floor was a publisher, who is today one of the big publishers in the country. Harold Arnstein, who is probably one of the best copyright attorneys in the country, had the penthouse. Someone called me up and said they would like me to audition an air check of a group that one of those big amateur shows on radio—this was 1951. It was the first act they ever recorded for King Records, for Federal. This cat came in with the air check, which was “Goodnight Irene,” which was a pop song at that time. I said I couldn’t use it, as it was neither fish nor fowl. It was not black enough to sound black or white enough to sound white, and I didn’t dig the kid who was singin’ lead. Trying to be a Broadway tenor singer, Broadway musical. Billy Ward called me up to see what I thought of it, and he was so insistent that I told him to bring the whole group down to audition in person. When I heard Clyde McPhatter sing, I said, “There’s your lead singer!” When I heard Bill Brown sing bass, he was the nearest thing to Ricky of the Ravens. I said, “There’s your two leads!” He said, “What kind of material are you looking for?” I said, “The Orioles,” who were very popular. He said, “That kinda shit? I can write those all day!” That was Billy Ward, who was a vocal coach with Rose Marse, who had backed them, an office on Broadway to coach vocal groups. He had no concept of rhythm and blues. He didn’t know what rhythm and blues was. Being a vocal coach, the Broadway show–type of material appealed to him. I played him some Orioles things, and he came back later with the group and some of that kind of material, and that’s when I signed them on. The first thing I did was “Do Something for Me” at Bell Studios on 8th Avenue, and I said, “Wow! That’s it!”

Or about the Platters:

I produced the first ones, the ones for Federal. I first met Tony [Williams] at the amateur show at the Club Alabam, Hunter Hancock’s show. He didn’t sound like a blues singer, but he impressed me. He didn’t even win third prize. He impressed me so much—to me, he was a modern Bill Kenny [of the Ink Spots]. I took him in my office that night and signed him. He lived in Jersey at the time and he brought his family back to L.A. I told him I couldn’t sell singles. “Let me put a quartet with you,” and I put a quartet called the Platters with him. I told them, “This is your new lead singer. Do you want to record for us, or don’t you?” That’s how I did it. I didn’t have the time to rehearse them, and we did one session and nothin’ happened with it. I was in my office at King, in L.A. one day, and I overheard someone come in and ask for some Platters records. I came out of my office to find out what his interest was. It was Buck Ram, and he was interested to see if I planned any further recordings. It turned out he was their manager and a vocal coach. I told him I knew of Tony’s talent and if he worked on the group, I’d do further records. He spent time on them. We did another session and it sold fairly well on the West Coast only. When they came in to do the next session, they came in two and a half hours late. We only had half an hour left at Radio Recorders. We had time to do only one take and that was “Only You.” Buck said, “We’ll do it over again, it won’t cost anything. Be damned I’m paying all these musicians and it will go into overtime.” At the time the Platters were doing background work for King and they wanted $50 a side. Syd Nathan got mad and said, “I can get any amount of groups to do ‘Doo Wop’ all over the place for $10 a side!” Buck Ram got upset and asked for the Platters’ release, which Syd gave. Bob Shad was in town at the time for Mercury. He picked up the Platters and they re-did “Only You” for Mercury. The only difference in the Mercury version was that they lowered the key; they used the same arrangement. We sued them and they “settled,” ’cause you’re not supposed to record the same song within five years. I made a deal between Federal and Mercury, whereas we got part of the money. They left us and got their first million-seller (laughs) and I had it in the can!

Ralph Bass also discovered James Brown.

Getting him was like a James Bond story. I found him down in Georgia. I heard a dub and it was so different that it knocked me out, cleaned me. I said, “Where can I find him?” I was in Atlanta, Georgia, at the time. It wasn’t called James Brown; it was a group named the Famous Flames. So a disc jockey and I drove down to Macon, Georgia, from Atlanta in a pouring rainstorm, pouring like crazy, and I found out that James had a manager named Clint Brandly, who had a nightclub and was the local promoter. James was out on parole to Brandly at the time. See, James had a very hard young life. James was a “society outcast.” Since Macon was such a Jim Crow town, I was told to meet Brandly by parking my car in front of a barbershop which was right across the street from a railroad station and when the Venetian blinds went up and down, to come on in. And I did. And I looked at Brandly and the cat said, “Yeah, I got a contract from Leonard Chess in my hand. I was waiting for Leonard Chess.” Well, Leonard Chess was on his way, ’cause Leonard always said to me, “I’ll never forgive you, ’cause you beat me to James Brown.” That was one thing Leonard always kept saying to me. Now, he was on his way, but, see, in those days, airplanes—if the weather was halfway bad, they couldn’t come in. They had no radar and all that jive they have today and so he was grounded. Well, anyway, I gave the cat $200 and I said, “Do you want to sign right now?” He says, “You got a deal. I’ll call the whole group in to sign the papers.” I don’t know James Brown from a hole in the ground, and I went to the club that night and I saw him do his show, crawling on his stomach and saying, “Please, please, please,”—he must have said “Please” for about ten minutes. I almost got fired for doing the record. After I collected my $200 that I paid out and paid for the expenses, I went back to St. Louis and King sent some people looking for me to tell me I was fired. I called the old man up and asked Syd what’s wrong. He says, “Man, you cut the worst piece of shit I ever heard in my life!” I said, “What are you talkin’ about?” He says, “Man, this man sounds like he’s stoned on the record, all he’s saying is one word!” I said, “Oh, you mean ‘Please’?” He says, “Yeah, all he’s saying is ‘Please, please, please, please, please.’” I says, “Well, I’ll tell you what, put the record out in Atlanta, Georgia, and if it doesn’t sell, baby, don’t fire me, I quit. I’ll walk clear all over the country to show you how bad this record is.” Well, the rest is history. Who knew then that James would be what he is today? He was a country kid then; he used to call me “Mr. Ralph.” He was so brow-beaten with that shit down there. I says, “Well, man, don’t call me no ‘Mr. Ralph.’ Either call me ‘Mr. Bass,’ or call me ‘Ralph,’ but don’t call me no ‘Mr. Ralph!’”

Ralph Bass still collects a pretty good amount of money from the ARMO publishing company that he co-owned with Syd Nathan on a fifty-fifty basis, and many hits are signed to this company. ARMO is named after the first initials of members of Ralph’s family. Except for Earl Bostic, he never produced for King, and left Federal in 1958. Federal continued for about six years, issuing many 45s by Freddie King and sides by Bobby King, Eddie Clearwater, and Smokey Smothers among others, but some, like James Brown, went to the mother company, King. In 1960 Johnny Otis became the A&R man on the West Coast for King Records, while Ralph became a producer for the Chess/Checker/Cadet/Argo company in Chicago, where he still works. Bass, described by Peter Guralnick as a “flamboyant, jive-talking hep-cat with a bulbous red nose and a penchant for colourful, slightly dated hip-talk,” has produced almost all the big names of the Chess stable, such as Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf, Etta James, Sonny Boy Williamson, Ramsey Lewis, Moms Mabley, and Pigmeat Markham. Now he feels he’s more or less a “watchdog” of the blues and is getting disappointed that his time of two-track recordings and blues is over—especially since Chess was recently sold for a mere $950,000 to the All Platinum Company and most of the old big names are dead or leaving the Chess family.