WE ARE THIRSTY

The Voices of the Printemps érable

To dive. They are afraid of drowning, but we want to drink. Life is drying out and the cities are becoming deserted of souls. Your numbers have populated everything, even our well-thinking heads.

Your numbers have eaten life and our ideas cry famine.1

— Catherine-Alexandre Briand, “Ça sent la poussière”

(my translation)

Hysteria seized much of the corporate media during the strike, as populist commentators erupted with uncommon vitriol at the young barbarians they imagined at the gates. Patently, the students had struck a nerve: “vandals,” “anarcho-communists,” “true savages,” “drunken ideologues,” “armed and masked goons,” “budding terrorists.” No invective seemed off limits to the most ardent defenders of the capitalist creed, not even the spectors of North Korea and Cuba.2 Threatened by the daily disruptions and the increasingly ambitious aims of the carrés rouges, the pitch of the media’s panic was matched only by the paternalism of their interventions. And indeed in the lead-up to the tuition increase, the dubious hegemony of those in favour of tuition increases within the establishment press was beyond qualification: Of 143 editorials and opinion pieces published in Montréal’s three francophone newspapers between 2005 and 2010 (the anglophone Postmedia-owned Gazette would certainly prove no outlier), only four opposed increasing tuition fees.3 Even Le Devoir, the province’s only independent and most respected newspaper, tilted heavily against students, with the bulk of its editorialists and columnists backing increases, even while its news reporting was deemed more fair-minded by the study conducted by IRIS’s Simon Tremblay-Pépin.4

As the strike sparked a society-wide debate during the spring of 2012, however, the students’ defenders emerged increasingly from the woodwork: Le Devoir redeemed itself by opening its pages wide to the hike’s opponents, and shone as a bastion both of democratic debate and of Québec’s dwindling humanist and social-democratic traditions. A few of La Presse’s columnists also bucked the trend and backed the students. And contrary to its mostly anti-student English-language equivalent CBC, the public broadcaster Radio-Canada was more balanced in its coverage, frequently engaging in in-depth analyses that did much to contextualize the students’ struggle both historically and globally. Yet with such few exceptions, the corporate-controlled media served largely as the zealous defenders of the neoliberal establishment, with none more rabidly anti-student than Pierre-Karl Péladeau’s Québécor outlets that account for 40 percent of Québec’s media.5 Freed of the shaming of the provincial press council — Québécor withdrew from the non-binding body in 2010 — its journalists often had few reserves in distorting or inventing the facts to better suit their youth-bashing ends.6

Yet outside the walls that house the media élites, a profound shift was under way. A few weeks after the strike was launched in February, support for the students began pouring in that presaged the historic scale of the movement. The CLASSE’s calls were reverberating far beyond the student base. For indeed, with scarce exceptions, when we listen to the voices that rallied to the students’ struggle, we don’t hear the echo of the establishment federations’ apology for neoliberalism. Their defence of educational accessibility was universally supported, but the bulk of the non-student actors who leapt into the fray were spurred by far greater aspirations. What we hear in fact, through the words of the students’ myriad supporters, are the overwhelming and unmistakable sounds of a society rising to challenge its élites and to rattle the foundations of their political order.

The most radical of the student associations had thus proved more attuned to the popular mood than any student association in Québec in decades. For in the public debate as in the on-the-ground mobilization, the influence of the establishment federations peaked near the end of March, when the unlimited general strike was still largely just a strike. But as the movement expanded and mutated in degrees to a full-blown social revolt, the FEUQ and FECQ often seemed like witless passengers caught in the march, surpassed by the events pushing them ineluctably toward a horizon they couldn’t see.

A new political imaginary signed in rouge:

Progressive Québec rises

The first expressions of support for the students arrived in the days leading up to the first Québec national march planned for March 22, 2012, and at first, it followed the well-worn pattern of mobilizations past. Québec’s three largest labour union federations, the CSN, CSQ and FTQ, came to the students’ defence on March 13, when CSQ president Réjéan Parent declared that “the struggle of Québec’s students is the struggle of all the citizens of Québec.”7 And indeed, while not “all” the citizens were to see it with quite the same eye, Parent’s profession of solidarity, ordinary on the surface, did ultimately presage the magnitude of the wave to come. For the rest of the spring, political and corporatist considerations led the union leaderships to remain prudently aloof of the student mobilization in public. Yet behind the scenes, the rallying of organized labour to the cause was without question and even reached far beyond the province’s borders: Unions from across Québec and Canada funnelled tens of thousands of dollars to the three main national student associations, along with enormous logistical and organizational support.8 Before the mobilization had truly taken flight, there were signs that Québec’s students had ignited a movement that progressives across Canada, where tuition levels are often multiples greater, felt a personal stake in.

The next day’s round of support was less ordinary, and traced the outlines of the public debate that would dominate the spring and summer. On March 14, the academic community closed ranks around the youth in a spectacular and excited display of solidarity, when more than 1,600 university and CEGEP professors9 — the figure would eventually climb to 2,40010 — issued a rousing declaration that warmly embraced and encouraged the protesters. Arriving as a veritable rush of wind at the students’ backs, their letter, timely and instructive in its language, went on to define the substance and tenor of much subsequent support. In “We are all students! The Manifesto of the Professeurs contre la hausse,”11 the academics boomed that they were lining up behind the “youth that is standing up” in their “democratic defence of university accessibility and in their justified opposition to the commercialization of education.”12 Yet most telling, perhaps, were the words reserved for the pocketbook discourse of the traditional student federations. The professors urged the FEUQ and FECQ, whose stance limited to cancelling the hike obviously failed to impress, to go “beyond [these] legitimate demands.” This movement, they stressed, was infinitely greater: “It’s the future of education and of Québec society that is at stake[…]. This strike represents the extension of numerous contestations that have emerged over the last few years in response to the subordination of the public good by private interests.”13

These “numerous contestations,” of course, were a clear reference to the Indignados, Aganaktismenoi and Occupiers; to the students of Chile, and of Britain as well. Largely overlooked by the corporate media, these social movements were a steady source of inspiration for many of Québec’s carrés rouges, perhaps few more than to the Professeurs contre la hausse whose own decentralized coalition was a mirror of the rising twenty-first century paradigm. It is their well-developed critiques that the academics draw from in the remainder of their letter to deplore Québec’s new status quo: the hegemony of financial and business interests and their class-based austerity agenda; the commercialist mutation of education and its undermining of the academy’s fundamental mission; the legitimacy of demands for free university education; and the humanist and civilizational vocation of the university. Inflated by the students’ “resistance,” the professors launched a full-throated endorsement of their revolutionary appeals to forge “a new political imaginary.”14 In rallying to the movement, the professors left no doubt as to what moved them to action: The CLASSE had declared the battle for the commons open, and Québec’s restless academics threw themselves headlong into the fray.

The parade of reinforcements continued two days later, when the pages of Le Devoir announced the formation of another group on March 16, this time at the initiative of parents. A Facebook group accompanied the formation of the Parents contre la hausse that counted 230 members on the day of its announcement.15 The header on the group’s website took up the cause of “a high-quality, democratic and accessible education system that genuinely contributes to the development of individuals and society.”16 The “call to parents” then continues, leaving little uncertainty as to the group’s values and goals: “Without prior debate worthy of the name, the government is thus imposing a choix de société: They are modelling us on the North American system, which rests on the equal payment of taxes and fees for all, thereby obviously impacting the less fortunate.”17 The parents propose instead the European model of “quasi-tuition-free education” and demand that “the state fund education as well as other public services based on citizens’ and businesses’ means.”18 In going far beyond concerns over accessibility and the financial precarity of students, the Parents contre la hausse thereby aligned themselves fully with the CLASSE’s call for a broader return to values of collectivism, humanism and social democracy. A week later, as high school students voted to walk out of classes and join the March 22 day of action, the parents were joined by the Commission scolaire de Montréal (CSDM), which publicly expressed its backing of the student cause.19

A month later, an exceptionally large crowd of thousands was marking May Day with a march against capitalism in Montréal.20 In 2012, the spirit of anti-capitalist revolt was in the air. Against this backdrop, Québec’s wider civil society stepped forward to announce its wholehearted solidarity with the students, with over two hundred prominent public figures signing a declaration under the title “We are with the students. We are together.” The open letter, published in the weekly Voir, drew from a wide array of Québec’s cultural, professional and intellectual communities, from artists, musicians, actors and film directors to academics, environmentalists, doctors, lawyers and economists.21 Sociologist Éric Pineault, one of the letter’s authors, echoed the professors’ admiration for the youth — tinged with his own latent riposte to Thatcherite TINAism — when he lauded the students for having “revived Québec’s economic imagination.”22 The letter itself was no less wide-eyed in its estimation of what the students had already accomplished: “This cry of the youth, which pushes us to break with our immobilisme [social and political paralysis], to recover our collective capacity to act and to work for the common good, we hear it,” answered the authors.23 Like those of the professors before them, their words were heavy with hope and awe, as if rushing to seize on a chance they once thought so distant, yet now had suddenly surfaced before their incredulous eyes: to strike at the neoliberals in a moment of weakness and at last begin to beat back the tide. It was evident that their impassioned leap into the melee was inspired not by the federations’ campaigns for more generous grants or the status quo in tuition fees, but by their shared dream of another, more just and democratic Québec. Indeed in their eyes, the Printemps érable had nothing to envy of Occupy Wall Street:

The questions raised are fundamental; they pertain to social governance. The students in the street are but the tip of the iceberg of a much larger movement that seeks to counter rising inequalities and social insecurity, the growing indebtedness of households, the poverty of those solitary people neglected by government policy and the environmental degradation engendered by an anachronistic model of development.24

Whether in the commercialization of post-secondary education, the privatization of health care services or the corporate exploitation of our natural resources embodied by the Plan Nord, this model, which “sabotages our public services” say the authors, is the regressive model of the neoliberal élites. Faced with this system that sees individuals charged “excessive fees in violation of the principles that helped build a modern Québec based on equality of opportunity,” the public figures answer together:

We want none of it[…]. We want no more of it.[…] And we are launching a pressing call to the associations, to the political parties, to the unions, to the professional bodies and to the citizens: In uniting our forces, we believe it’s possible to make the winds of the Québécois spring blow stronger still.25

Their words were heard. In the following days and weeks, many groups of different sizes and under various banners would form to answer the call: Infirmières (nurses) contre la hausse, Chomeuses et chomeurs (the unemployed) contre la hausse, Travailleurs (workers) contre la hausse, Écrivains (writers) contre la hausse, Mères en colère et solidaires (mothers), Têtes blanches, carré rouge (seniors) and on it went.26 The tuition hike itself had become almost secondary to the fire it lit in the hearts of Québec’s progressives. This was now their battle, inspired by a collective dream and the newly ignited hope of the possible.

In between these large-scale outpourings of solidarity from influential (and less influential) segments of society, prominent intellectuals and former politicians lined up in the pages of Le Devoir to outline similar arguments.“We have a hard time understanding how the current government can consider dismantling one of the major gains of Québec’s modernization,” deplored Jacques-Yvan Morin on March 22, who served as René Lévesque’s first education minister from 1976–1981.27 He was later joined by Jean Garon, Jacques Parizeau’s education minister in 1994, who also lent his support to the students on April 17 by endorsing the CLASSE’s campaign for free university education.28 Former premier (and one-time student leader) Bernard Landry completed the triad of PQ stalwarts when he followed suit on May 15 and also proposed free undergraduate education in the interests of resolving the crisis.29

Professors emeritus Guy Rocher and George Leroux, the former a member of the Parent Commission in the 1960s and one of the report’s co-authors, along with professors Christian Nadeau and Yvan Perrier, all signed letters expanding on the arguments from the manifesto of the Professeurs contre la hausse. They variously aimed at questioning the values underlying the government’s view of students’ “fair share,” at rekindling the long-time aspiration (and demonstrating the feasibility) of free university education, at highlighting the inherently regressive nature of tuition fees and at pilfering the mounting trend toward the commercialization of public services. Echoing the CLASSE’s invocation of the Plan Nord as the sign of a wider shift in governance paradigms, Guy Rocher sounded incredulous before the government’s priorities: “How can we provide such gifts to companies who exploit our natural resources and at the same time refuse students the investment needed to ensure their future at university?”30 Indeed, Rocher’s was a question that imposed itself repeatedly throughout the student crisis. The government had built the entire rationale for the hike on the assertion that the state lacked the sufficient resources to fund education, and yet two words, “Plan Nord,” sufficed in easily washing away the façade. Beneath it we saw the image of an élite that was growing ever more emboldened in its race to sell off the commons to powerful private actors. To the Rochers, Lerouxs, Nadeaus and Perriers, it was eminently clear that the students’ struggle was at heart a struggle over the very future of Québec.31

The force and fire with which others took up the baton spoke to the pulsing vein that the students had ruptured, but more, to the surging hope that suddenly inflated the hearts of so many. On May 30, a rousing appeal entitled “We are immense” appeared in the pages of Le Devoir, in which actor and stage director Philippe Ducros composed a moving paean to the young citizens in the streets. To Ducros’s eyes, the events of the Printemps érable were “historic” and the students, “visionary.”

For over one hundred days … Little by little, step by step, in spite of the decadent cynicism and outrageous condescension on the part of our leaders, Québec rises, calls for solidarity, and proclaims its absolute refusal (“ras-le-bol”) of economic fundamentalism. What is happening here is historic, as the struggle reaches far beyond our borders and stakes its positions on issues far larger than tuition fees.

For over one hundred days …

In spite of the tear gas, in spite of the truncheons and mass arrests, we are redefining the world. Instead of once more suffering the neoliberal enslavement, we are forcing History, little by little, to take the next step, to cross the barricades of an unbridled and sacrosanct capitalism’s preconceived ideas.

The mirage no longer holds. We are thirsty.

This commercialization of education and the rerouting of our places of knowledge toward corporate interests are inscribed within an ideology that envelops all the spheres of our lives, from the industrialization of art to the privatization of health care, from the deforestation of the Amazon, to the gutting of Africa by the mining industry.

The students of Québec are visionary. They have opened the way. We are now a new buoy in the dangerous channel of the changing global paradigm. After the Jasmine Revolution and the Arab Spring, after the Indignados of Spain, the Occupy movement, the insurrections of London and the strikes of Athens, here we are, the bearers of the torch. All around the world, people are rising up, indignant. We have taken up the reins. We speak now in the name of a global population in search of justice, solidarity, equity.

What we carry surpasses us. […]

We are giants. And it takes giants to force History to take the next step.32

Other allies came before Ducros and others came after, all marching almost invariably along the path prepared by the CLASSE. Whereas polls throughout the spring consistently suggested a public heavily divided (though slanted against the students), it was clear that the broad call to revolt launched by the radical current of the movement had tapped into a deep-seated thirst among Québec’s seas of restless progressives, tracing an arc that ran from Europe, to Wall Street and finally to Montréal. Indeed, the CLASSE’s themes overtook the arguments of the federations to become what Pineault calls the “hegemonic discourse” of the movement.33 For it was their shared dream that rallied civil society and triggered a broad-based social struggle whose origins long lay simmering, awaiting a spark — when the youth of Québec at last arose to strike the match.

Voices of the underground: The Twittersphere speaks

In Québec, the student spring saw the CLASSE emerge as the children of the social media revolution, with their campaigns demonstrating an unrivalled grasp of the Web 2.0’s inner architecture and potential. Indeed as CLASSE activists Renaud Poirier St-Pierre and Phillippe Ethier recall, in the early days of the strike movement the carrés rouges seemed to exert a virtual monopoly over the social media debate, which was later slightly attenuated but never successfully challenged by their opponents.34 Yet as astute as the CLASSE’s social media strategies were, the preponderance of the pro-student camp in the Twittersphere also spoke to something deeper and more portentous: namely, the chasm in social and political values between the Net generation and their elders. Indeed according to self-disclosed age in a recent sample study of 36 million Twitter users worldwide, youth aged 18–25 may represent upwards of 73.7 percent of the Twitter community.35 And while these numbers may admittedly be exaggerated — younger users are presumed to be less hesitant in disclosing age — there are ample studies, most notably a 2012 report by Pew Research as well as another by Sysomos Inc., that corroborate the overwhelming youth bias in the use of social media.36 Simply put, social media is the phenomenon of a generation.

It was perhaps inevitable then that Twitter would become the core instrument of the student struggle, serving as an online agora for civic debates, a decentralized infrastructure of organization and coordination and an unfiltered and up-to-the-second news, image and video feed for all things related to the movement. Videos of widely varying budgets were diffused through social media, produced by individuals and organizations ranging from leftist think-tank IRIS, to OWS offshoot 99% Québec, to many artists, filmmakers, activists and others.37 As an important sign of the growing role of the anglophone community in Québécois social movements, Concordia University’s CUTV community broadcaster became a central pillar of the mobilization, and the movement’s unofficial video feed. Where the mainstream media wouldn’t tread, the CUTV team was on the ground to provide uninterrupted, real-time and bilingual reporting from within every protest (whose openly pro-student bias, interestingly, was defended for exposing the opposite bias of the establishment press). Facilitated by its hand-held video equipment, its coverage was broadcast live on its website and complemented with constant updates over Twitter, despite frequent on-air attacks by the Service de Police de la Ville de Montréal (SPVM), who twice destroyed the student network’s equipment.38

Olivier Beauschene is a private sector data analyst who performed in-depth analyses of Twitter use during the Printemps érable, designing graphs that grouped and visualized the content of tweets sent, as well as the structures of influence within the Twitter community.39 Beauchesne’s studies, published in Le Devoir, collected more than 500,000 tweets sent from mid-February to June 27, 2012, identified by a series of hashtags linked to the student contestation, of which 320,000 were marked by the most ubiquitous, #GGI.40 He then used an algorithm to group tweets according to subject and vocabulary, and graphed them in constellations whereby similar topics appear clustered together. Finally, he listed the principal hashtags used and recipients of the tweets. In the lead, the SPVM figured prominently, followed distantly by La Presse, the ASSÉ, Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, Le Devoir, leftist MNA Amir Khadir and then CUTV News.41

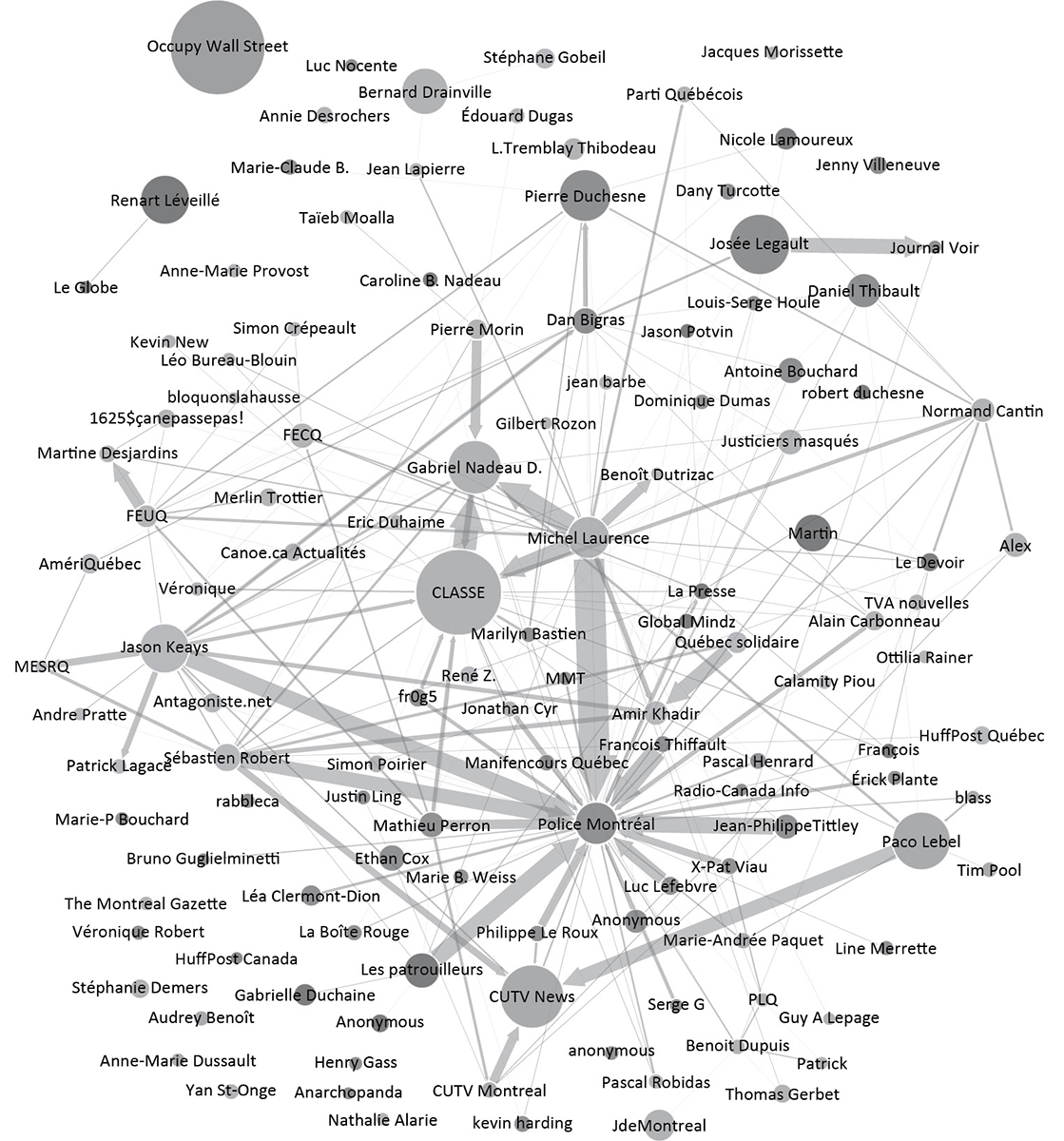

The size of circles illustrates the online influence of Twitter users, while the arrows map the interactions. Image credit: Olivier Beauschene.

In a second graph current to June 1, more significant to identifying the most influential voices online, Beauschene analyzed and visualized the structures of the Twitter exchanges as identified by the @ sign, which directs a user’s publicly visible message to its recipient (for example, @ SPVM). Based on 21,000 distinct individuals engaging in 235,000 conversations (including more than 400,000 tweets over all), Beauschene was able to construct a graph (see Figure 1) where the size of circles illustrates users’ degrees of influence, as measured by the total volume of retweets (and thus scope of diffusion) received by their messages.42 The data he gathered show the CLASSE, Nadeau-Dubois and their allies (like Josée Legault from the weekly Voir) clearly dominating the Twitter community, with the FEUQ, FECQ and their respective leaderships confined to virtual irrelevance — in the company of establishment media and political parties (with the lone exceptions being former journalists and PQ MNAs Bernard Drainville and Pierre Duchesne). Revealingly, the only Twitter user with greater online influence than the CLASSE during the strike was one located south of the border: Occupy Wall Street, which actively followed and supported the revolt raging across their northern frontier.43 In fact, Québec had never been so active on Twitter, with St-Pierre and Ethier even claiming that “before the strike, for the majority of young Quebecers […] Twitter simply didn’t exist.”44 If they are correct, then the student spring truly propelled our youth into the social media age: For one week in the spring of 2012, Québec’s #GGI became one of the top five tweeted subjects on the planet.45

Strike a match: The time of the Québecois spring

In 2012, the CLASSE rallied Québec’s progressives around their democratic struggle to rescue the commons from the rapaciousness of the élites. Nothing in their success was foretold, and indeed, the impact of the CLASSE could well have stayed confined to the activist core of the student population, as was the case with the ASSÉ’s prior mobilizations. But this time, it didn’t. It should go without saying that success or failure in campaigns can only rely on effective organization to a point. Strike as hard or as persistently as you may, without a deeper resonance of the cause in society, all the well-placed tinder in the world will remain moist and unwilling to catch.

But evidently, the days we are living are no ordinary times. The CLASSE rode the wave of Occupy Wall Street to lead a broad-based challenge to the political order of Québec’s One Percent. And in spite of government and media attempts to sideline them as marginals, the overwhelming pull exerted by their discourse on society’s ground level told a different tale. Letter upon letter (and tweet upon tweet) booming excited encouragement were the unmistakable sign that their finger had been placed directly on the pulse of the progressive electorate and six long and intensely charged months, the sign that their struggle had ruptured a vein in a frantic search for an outlet. The words of the students’ backers confirm an intuition: that the hundreds of thousands of citizens were not in the streets all that time only to challenge a tuition hike. Indeed, the thousands of professors would perhaps not have found themselves so eagerly by their sides but for that — and certainly not the artists, actors and film directors, nor the environmentalists, economists, doctors, nurses, seniors and lawyers. Yet in the streets and by the students’ sides they all were, with their small patch of red felt displayed proudly — not for what it signified to others, but for what it signified to them. Ceci n’est pas une grève étudiante. This was not a student strike, but a spring awakening — though summer, as so often in Québec, continues to wait.

Students march in a demonstration called by the student associations of the Université de Montréal on March 27, 2012.

Young protesters take part in a CLASSE demonstration on April 4, 2012, in Montréal.

Red and green converge in Montréal as 250,000 mark a historic rally “for the common good” on Earth Day, April 22, 2012.

Students lighten the mood with a protest celebration in Montréal on May 11, 2012.

A musical parade of carrés rouges brings Montréal’s streets to life.

The carrés rouges make a statement after the CEGEP de Valleyfield ordered classes to resume in April in spite of strike mandates.

Students occupy UQÀM on May 16 in response to court injunctions ordering the resumption of courses. Along the floor is scrawled the message: “Occupy our neighbourhoods.”

Anarchopanda looks on as riot police prepare to brutally dislodge student picketers at the CEGEP de Rosemont on May 14, 2012.

A demonstrator captures his generation’s attitude toward authority at a maNUfestation on May 16, 2012.

For months, the police helicopter became a regular feature of the Montréal sky.

A lawyer addresses a crowd gathered at Place Émilie-Gamelin during a demonstration against Bill 78 on May 28, 2012.

Protesters bang pots and pans (and channel Guy Fawkes) to protest Bill 78 in a casseroles march on May 30, 2012, in Montréal.

A maNUfestation on June 7, 2012, takes on the feel of a carnival.

Swarms of heavily armed SQ officers were deployed in Montréal to guard the F1 Grand Prix from protesters in June 2012.

Protesters flood Montréal’s streets for a national march against neoliberalism on July 22, 2012.