THE IRON BOOT OF JEAN CHAREST

Crush a Flower, a Thousand Will Bloom

I’ve never been arrested, but I know: I’ve been on file for quite some time. I live with the representative of a student association. Every time the members meet at my house, police cars park on my street. Some of my friends have been arrested at their apartments for no reason. Others, at the G20 in Toronto, were imprisoned three days in atrocious conditions. They weren’t arrested while demonstrating, but while arriving back at the bus that was supposed to bring them back to Montréal.[…]

I’m afraid, all of the time. And I can no longer control my rage. It’s time we opened our eyes.1

— Maryse Andraos, “À bas les masques, Big Brother”

(my translation)

The spectacular rejection of the entente had shone a light on the government’s incompetence and disconnect in managing the worst social crisis to rock Québec in over a half-century.2 Those who plot from within a bunker, it seems, are the ones most enamoured of their own schemes. Yet Charest had far from played his final card, and the collateral from the Liberals’ ideological warfare had yet to be fully tallied. Retreating or compromising on his “cultural revolution” was out of the question, but the situation could not continue like this much longer. The “sovereign authority, the decisive figure of the Father,”3 was poised to take matters into his own hands.

Victoriaville had rattled the political establishment with the ferocity of the violence, to the point where the Parti Québécois demanded a public inquiry into the Sûreté du Québec’s actions that left two students dangling between life and death.4 The injuries barely fazed the Liberals. In the Assemblée nationale on May 10, public safety minister Robert Dutil rejected the demands from the Opposition, but not without venturing his own constructive proposal: “What police should do is increase the use of force to the necessary level in order to counter the violence while using measures least susceptible to cause injury to protesters.”5 The incoherent and brutally irresponsible comments by the minister — reinforced by Charest’s blaming of students for the persistence of the crisis and his bewildering claim of having “made all necessary efforts” to resolve it6 — presaged a final radicalization of the government offensive. The Liberals had gambled everything on the mobilization fading away from its own exhaustion. Now, their clock had run out.

Suspicions of an impending crackdown began to circulate when deputy premier and education minister Line Beauchamp issued her surprise resignation on May 13. She was “no longer a part of the solution,” she said, but her final declarations enlightened as much as her decision shocked. In her departing press conference, Beauchamp lamented, incredulous, that when she asked the student spokespersons if they had confidence in their elected representatives, the answer, swift and unhesitant, was no. This response, so intuitive and even self-evident for many of our generation, was apparently something Beauchamp was incapable of conceiving, and proved so unconscionable as to precipitate an abrupt end to her fourteen-year political career.7 The next day finance minister Raymond Bachand took to the airwaves on Radio-Canada to warn of “Marxists” and “anti-capitalist” fringe groups (heretics! barbarians!) trying to destabilize Montréal’s economy. With such comic hysteria shouting from backstage, Michelle Courchesne took over the reins as education minister and met the student leaders to reopen a dialogue.8

Those brief informal encounters were destined to be but a sideshow. The power behind the scenes had other plans brewing; historic plans that would bring the tenacious social crisis to the last brink and spark the final and most spectacular transformation of the Printemps érable. Repeated calls by third parties for mediation, including by respected past Liberal minister Claude Castonguay, had been met with cold refusal by the government since March.9 Now, rumours filtered out through the press suggesting that Charest was readying a fateful last act that bore the full force of the state’s coercive muscle. Addressing the media, Léo Bureau-Blouin urged the premier in his most earnest tones to act as a “good family father” and “speak with his children” rather than “calling the police” to settle their problems.10 Yet all urgings by student leaders and all pleas by the Official Opposition and the Barreau du Québec (the Québec Bar Association) had fallen on deaf ears.11 Without having once sat down at the table to discuss the crisis with student representatives, Charest now appeared as “the figure of the paternal authority in its most sombre light: the father that pushes aside the mother Beauchamp to better beat his children.”12

Bill 78: The tyranny of their economy made law

On May 17, Bill 78, officially entitled An Act to enable students to receive instruction from the post-secondary institutions they attend, was submitted to the Assemblée nationale by the Liberal government. Across the province, all eyes were riveted on the legislature as never before. For twenty hours, MNAs clashed late into the night as the PQ spared no indignation at what political scientist Pascale Dufour calls the “most repressive legislative cocktail” seen in Québec since the 1970 October Crisis. Back then, Ottawa invoked the War Measures Act after the Front de Libération du Québec kidnapped a cabinet member and a British diplomat, later murdering the former.13 No less, it seemed, was required to meet the dire threat posed by Québec’s protesting youth. Yet the Opposition was perfectly incapable of doing the slightest thing in the face of the Liberals’ parliamentary majority. Panic aired across social media and on the mainstream airwaves, as the democratic gains of one of the most stable polities on Earth seemed to be unravelling so quickly before our eyes. Yet there was nothing anyone could do. The right-wing populists in the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) partnered up with the governing majority, and Bill 78 was passed into law on May 18 to become Law 12.

The “truncheon law,” as it was quickly labelled, was utterly without precedent in the history of Québec and engendered wholesale ruptures on a variety of fronts.14 “Rarely have we seen so flagrant an aggression committed against the fundamental rights that have undergirded social and political action in Québec for decades.” This was how dozens of historians denounced the Liberals’ move in a joint declaration that was just as rare as the affront that invited it.15 The title of their open letter said it all: “A rogue law and an infamy.”16 Yet Bill 78’s full-barrelled assault on the foundations of the Québec student movement, we now know, had been in preparation from the strike’s very onset.17 In hindsight this knowledge greatly reframes the government’s motives, bringing the jagged contours of the Liberals’ ideological designs into the light of day. This was no measure of last resort devised in the heat of a crisis, but a sinister bid at reshaping Québec’s future by means of opaque schemes and social warfare, and through a deliberate end run around the unpredictable inconveniences of democratic debate. The doctrinaires held so fervently to the righteousness of their ends that the democratic rights and social peace of their people were confined to the margins of consideration — collateral damage, on the path to the promised land.

The Law’s reengineering project was nothing if not ambitious. In all past student strikes, part of the course hours lost were considered an inevitable cost of the walkout, which was seen as a learning experience in and of itself that many professors (and politicians) had themselves once participated in.18 Yet in neoliberal Québec the students were to be punished for robbing the economy of its labour force; education was now “a contracted service that must be rendered once it is paid [by the state.]”19 To repay the “debt that students owed to society,”20 they would therefore be made to work: The current semester was suspended and the summer one cancelled, and an immediate summer break was begun, ending between August 17 and 30. The suspended winter semester was to be made up at the end of summer, with the equivalent of twelve weeks of courses condensed into one month at the expense of students’ evenings and Saturdays, and the following semester leading directly into Winter 2013. Yet student aid would not be prolonged to account for the changes, leaving many strikers in precarious financial straits.21 The shortened summer break, suggested Père Charest, should thus be used “to calm the nerves,” but also and more importantly, “to work.”22 Students lost one month of their summer vacation and the entire break between the recovered semester and the following one, and their winter break of the following year was shortened as well. Yet the students were not the only ones to be made to repay their “debts.” The law ordered “all employees” (mostly professors) to show up for work “as of 7:00 a.m. on 19 May 2012,” and to “perform all duties attached to their respective functions, according to the applicable conditions of employment, without any stoppage, slowdown, reduction or degradation of their normal activities.”23 Everything was in place to enforce the resumption of all “normal” activities, as the tyranny of the élites’ economy was mobilized with the force of the state’s coercive muscle.

These were far from the most incendiary of the law’s provisions, nor were they those with the broadest, or most troubling, implications. With the final aim of ending all disturbances in the streets, the government saw fit to suspend the civil liberties of all of Québec’s citizens. Law 12, still known colloquially as loi 78, was centred on “provisions to maintain peace, order and public security” that barred all gatherings of more than fifty people (changed from ten under pressure from the PQ) where an itinerary had not been approved by police at least eight hours in advance, and gave police forces unilateral authority to modify the venue or route according to their whims.24 The penalties attached were draconian: Per diem fines were levied on individuals ($1,000–5,000 per offence); representatives of student or employee associations or organizers of an illegal demonstration ($7,000–35,000); and student associations, institutions and associations of employees ($25,000–125,000) found in contravention, with fines doubled for second and subsequent offences.25 The penalties, however, didn’t stop at proven violations. “Anyone who helps or induces a person to commit an offence” was to be deemed to have committed it themselves, as were student representatives and associations who failed to preempt offences by organizers of demonstrations in which they participate.26 All protests were banned within fifty metres of educational institutions, and both the teachers’ and students’ unions were charged with enforcing the compliance of their members.27

Once more, the representatives and spokespersons of an autonomous and grassroots movement were tasked by the Liberals with bringing their “troops” into line, and this time at the risk of their associations being crippled and destroyed under the weight of financial penalties. The wording of the text was left deliberately vague, and the chilling effect desired by the government, abundantly clear: to project the impression, constitutional or not, that “anyone could be incarcerated for being found within the proximity of a demonstration of more than fifty people”28 — and thus with the help of intimidation, to effectively stamp out all dissent. The government crackdown had begun to take on distinctly Orwellian airs: Questioned in the Assemblée nationale on whether a tweet could constitute an illegal call to assembly under the Law, education minister Michelle Courchesne told the Opposition that she would leave it up to police to decide.29 With the province providing the cover, Québec City and Montréal then both passed municipal bylaws imposing steep fines (in the former case, up to $1,000) for participating in a protest whose itinerary had not been approved in advance or for wearing masks of any kind during a protest.30

In the space of a week, the arbitrary power of the state over its people had expanded by a frightful bound. The Collectif de débrayage writes that the “most pernicious character” of the Law was contained “without any doubt in its rendering equivalent of the act and the omission, repeated at numerous points in the text.”31 This was the authoritarian reflex of a security state on paranoid overdrive, and in that sense at least — as a historical and ideological document — the text of Bill 78 is of high value indeed. For fundamentally, its provisions shone a light of rare forthrightness on the interests and ideals that contemporary power structures are mobilized to defend and on the fears that move them to risk such utter extremes.32

In truth, what we term “laws of exception” (lois d’exception) have become anything but, as we see with the growing recourse to legislative suspensions of rights since the 1970s in both Québec and Canada.33 Measures that were once limited to wartime are today deployed as a matter of course against threats of the capitalist élite’s power: “From the exterior enemy of the Nazi or Communist, we’ve transitioned to the interior enemy of the Islamist, anarchist or radical environmentalist through a quasi-natural evolution.”34 Robert Bourassa’s crackdown on the unions’ Front commun in 1972 and imprisonment of their leaders was an ominous precedent on this path, criminalizing labour disruptions and casting the state as the defender of the economy, and by supposed extension, of the public interest. René Lévesque followed suit in 1983 with his own legislative repression of a labour mobilization, with his Law 111 allowing the dismissal of all teachers who failed to return to work.35 Between 1982 and 1999 alone, both Liberal and Péquiste governments enacted no fewer than thirteen such “special laws” to crush labour actions and force a return to economic normalcy.36 Yet in an economic system whose gains are skewed toward the top, the mythical equivalency between the economy and the public good falls away to be replaced by the image of an oligarchy simply safeguarding its dominance. And behind this shield upon which was carved their most central lie, the threats to the ruling class were being marked as the enemies of the neoliberal state, and stamped out.

Ironically for a premier who studiously refused the label “strike,” the Law was the first to import into a student conflict many of the same repressive measures used to suppress labour actions of recent decades. In its essence, it was thus the latest expression of the mounting trend toward the criminalization of any and all disruptions to the economic flow. 37 And in drawing the fangs of the Liberals, Bill 78 exposed the open vein that the carrés rouges had so ardently struck.

The target of the special law is […] clear: anyone who contributes directly or indirectly to interrupting the normal course of things. The special law takes meticulous care to define the broad spectrum of strike practices. A striker is anyone who doesn’t fulfill their function: every professor that doesn’t teach, every student that doesn’t study or every janitor that doesn’t sweep. But Bill 78 goes even further, since the “slowdown, reduction or degradation” becomes just as reprehensible as the pure and simple stoppage. One must not simply fulfill their function then, but fulfill it with zeal, fulfill it to perfection.38

Black against white, in the clearest language possible, lay the bald enunciation of contemporary capitalism’s most totalitarian ambitions: its remodelling of the citizen, the human, into an obedient soldier in the service of the economy’s onward march — or, more accurately, in the service of the class that claims most of the current system’s benefits. In retrospect, the very hysteria of the government response can perhaps only be read as the animal instincts of a power whose interests are threatened. Charest’s eyes may well have been riveted there, for it becomes difficult to otherwise imagine how so shrewd a politician could not have predicted the scale of the shock his offensive would provoke — if not as a beast who is cornered, their reason clouded by fear.

Dear Leader, we defy you: Québec disobeys

The loi spéciale instantly unleashed a torrent in Québec and signalled a watershed in the history of the Printemps érable. Confirming the Liberals’ rupture with Québec’s historic relationship with the student movement, Charest’s law laid bare the smallness of a government whose spiteful bid at destroying the student associations was easily identified just below the Law’s surface. Viewed by many as the autocratic excess of a corrupt and increasingly isolated government, the spirited condemnations rained down from all sides: The Barreau du Québec, Canadian Civil Liberties Association and later the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse, Québec’s human rights watchdog, all declared it a violation of fundamental rights guaranteed under the Québec and Canadian charters. Amnesty International and the United Nations also leapt into the fray with statements accusing the government of breaching its international and human rights obligations.

On the side of labour, the rage of the three main union leaders erupted with uncommon vitriol. “Québec must not become a police state,” boomed Michel Arsenault of the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec (FTQ), channelling the shock and incredulity of the presidents of the FTQ, CSQ and CSN, who were all beside themselves in decrying loi 78 as the worst law they’d seen in their lifetimes. “We’re not in North Korea, being made to laugh or cry when the premier passes by!”39 CSN head Louis Roy fumed that the Liberals were a bunch of “impotent old farts (mon’oncles)” attacking the generation that will “toss them out,” and spat that the Law was “worthy of a banana republic.”40 The CSQ’s Réjéan Parent said he had “never seen such a perfidious law;” Arsenault chimed in that it was motivated by the “spite, anger and vengeance of the Liberal Party.”41 And the next morning the smaller teachers’ union, the Fédération autonome de l’enseignement, purchased a full-page ad in La Presse in which a close-up of Charest sat emblazoned above the potent j’accuse: “Disgrace has a face.”42

The presidents of the FEUQ and FECQ were in a state of shock, visibly grasping for the just words to capture and condemn the premier’s untoward act of aggression. It wasn’t long before their traditionally measured tones gave way to heated declarations of all-out war.43 “We’ve just told youth that everything they’ve done, all they’ve created as a social movement in the last fourteen weeks, that it will all now be criminal,” intoned a stunned and exasperated Martine Desjardins. Bureau-Blouin stood just as aghast at the government’s hostility and before an act that he could only read as an attempt “to slowly kill the student associations, but also to silence the voice of the population.”44 Most trenchant of all was Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, who raised the alarm on the government’s slide into authoritarianism. In imposing an emergency law which violated “fundamental liberties” and “recognized constitutional rights,” said GND, Charest was “using a state of emergency to apply a special law in the short term, while knowing full well that judicial proceedings are too long to allow us to challenge it. It’s an abuse of power.” Nadeau-Dubois confides in his book that he “cried of rage” on the night of Bill 78’s passage: “I’m convinced that the sense of disgust I felt was shared by hundreds of thousands of people. The bond of trust between a great number of Quebecers and their democratic institutions, already weak, had finished unravelling with this vote.”45 Asked that day by the press whether the CLASSE would respect the Law, Nadeau-Dubois replied curtly: “We’ll see.”46

Charest defended his loi spéciale with the need to re-establish social peace; instead, he’d reached for the last drum of gasoline to douse the flames. Immediately after the bill’s passage and in the nights that followed, the usual crowd of a couple thousand nightly marchers swelled by thousands upon thousands, as the largest of the spring’s nightly demonstrations became the outlets for society’s rage against loi 78. Police no longer entertained the charade of waiting for (or inciting) a pebble thrown or window broken before attacking the peaceful majority. Newly empowered, the guardians of the power declared them illegal before they began, launching hostilities that provoked intense street battles that played out night after night with a frightful escalation. The rebellion in the streets of Montréal those nights knew no parallel in the city’s history. In the Quartier Latin, protesters threw debris onto a bonfire that soared upwards from the centre of Rue St-Denis, almost as if to brush the SQ helicopters whose hums had become etched into the night sky for months. The dancing and singing crowds gathered around the flames to cheer on the havoc, and mounted barricades in the streets to hold back the SPVM riot squads, now reinforced by the provincial SQ, who would soon arrive around any corner. And when they did, it was war.

Shields banging, the phalanxes marched, and anyone caught in the path of their bulldozer was propelled to the pavement, repeatedly at times, with the brutal barrage of their batons. It mattered little that the street was a vibrant nightlife hub lined with busy bars and restaurants, or that peaceful bystanders filled the streets and flanked both sides. As people poured out onto their balconies to watch over and loudly encourage the resistance from above, bars were drowned in tear gas and pepper spray as cops lashed out in a storm of indiscriminate brutality, flailing about at the slightest verbal provocation by indignant patrons.47 Shop and restaurant owners were detained in their own establishments, and even the elderly and tourists couldn’t evade the arbitrary arrests of a police force run rampant, run rabid. Sexual assaults and racist and homophobic slurs from the SPVM attained their apogee, as plastic bullets fired gleefully, “in the ass, my son of a bitch” (“dans les fesses, mon câlisse”) became the emblem of a security force erupting with such “flagrant delight (jouissance) […] in the carnage.”48 The CUTV anchor was pummelled to the ground and the cameraman was batoned live on camera. Another man had a close brush with death after a plastic bullet lacerated his liver on the night of May 18. But the gravity of one man’s wounds were barely a footnote to the struggle at this point. One girl’s letter to a friend evoked the reigning brutality.

It’s true that I have one (two, I don’t really know) ribs broken. It’s also true that it wasn’t pretty. Thrown against the wall, window broken, the frame coming up to my ribs, and with the cop not pulling his punches, well, crunch.[…] Even though I was injured, the adrenaline still numbed the pain, and what I had seemed like scratches compared to others: lacerated faces, certainly other ribs fractured, respiratory distresses, bruised and swollen thighs and abdomens[…]. The boy next to me in the van was practically having convulsions, certainly a cranial trauma, his face bloodied, hyperventilating, and the cops were still having fun ridiculing him, telling him to stop his joking. Really, for weeks now, unspeakable violence.49

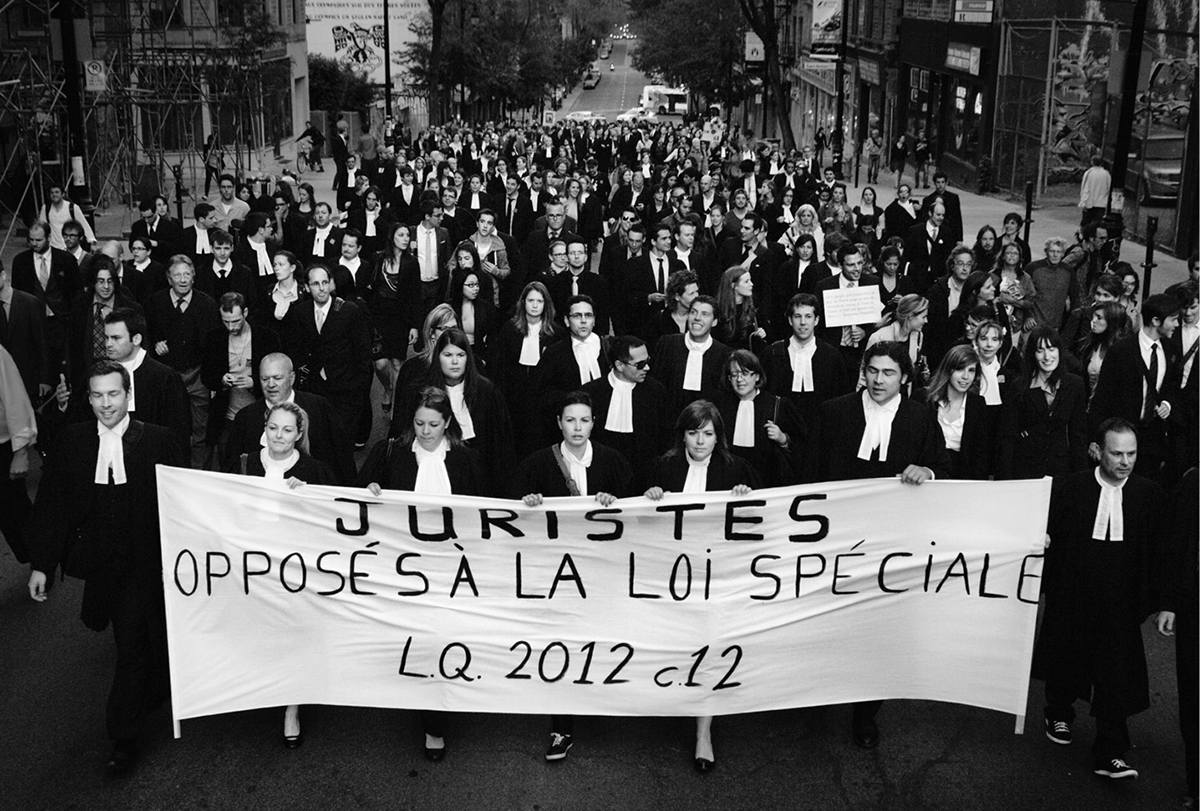

In the one week after Bill 78 was passed, the unprecedented wave of mass arrests totalled over a thousand people in Montréal and Québec City alone, with police kettling 518 protesters on May 23 despite providing no warning or ability to flee.50 Stunned by the government’s historic affront to “freedom of expression, association and peaceful protest,” the judicial community now mobilized like never before. Departing from the Palais de Justice on May 28 clad in the official robes of their profession, hundreds of lawyers and notaries marched downtown in a silent procession that aimed a deafening message of condemnation at Charest’s Law.51 Indeed, having attained a new summit, the state’s campaign of violence and intimidation, camouflaged by government deflections against students throughout the spring, was no longer possible to deny. Yet the repression didn’t stop with the brutality, the arrests or the draconian conditions for release imposed by the courts. The conditions of detention were horrendous as well. People were kept handcuffed in buses for as long as seven hours without being informed of their charges, were prevented from calling friends and relatives, and deprived of basic necessities such as access to water, medication or bathrooms.52 Nothing out of the ordinary in the new normal of 2012, however; Montrealers had only discovered that spring what many Canadians, including Quebecers, already had in Toronto during the G20 Summit in 2010, where over 1,200 people were arrested in two days, shattering all Canadian records.53

Lawyers march silently through Montréal on May 28, 2012, to protest Bill 78.

As exhibited with escalating intensity throughout the spring, the SPVM had definitively taken on “the traits of a paramilitary militia, making its law and order reign without worrying about the slightest accountability toward the population it is meant ‘to serve and to protect.’”54 Many Montrealers would be forgiven for thinking they were hallucinating before the dystopic scenes that had engulfed their streets. Our festive city, its traditions steeped in pacifism, had become a battleground and our elected government, the oppressor. Many protesters would suffer symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in the months that followed.55 But in the heat of rebellion, the people of Québec would not be cowed.

Montréal no longer slept, and neither would the exhausted police be left a minute’s rest. From the break of dawn, one protest followed the next at an “infernal” rhythm — one at noon, one in the afternoon and all just rehearsals for the evening’s battalions.56 Night after night, tens of thousands of demonstrators flooded the streets, defying and evading the security forces as they dispersed into various demos and converged anew in repetition, marauding endlessly through the city streets until the hours preceding dawn. The CUTV stream never went silent anymore, as on Twitter, the hashtags #GGI and #manifencours had become two of the most widely used in the world. Records of police brutality raced through the cybersphere, as citizens, tracking the crowds’ processions online, arrived in steady streams to reinforce the embattled marchers.57 The raucous crowds wound their way at times all the way to Charest’s home in its rich Westmount enclave, where they massed outside to launch their joyous defiance against his windows: to the tune of a schoolyard taunt (na-na, na-na-na), in unison, “We’re more than fifty, we’re more than fifty…” The new chant would become a part of the folklore of the Printemps érable. But none could capture the surging elation of a mass rebellion quite like another one, forever signed with a carré rouge: “La loi spéciale, on s’en câlisse, la loi spéciale…” In the proud profanity of the Québécois street, the people answered Charest and the police that faced them: “We don’t give a fuck” about your special law. The Collectif de débrayage, which named its essay for the profane chant that embodied the movement’s (and this generation’s) anti-authoritarian ethos, writes that “Responding ‘On s’en câlisse’ to the special law transforms into bravado what was meant as the most terrifying moment of power: the state of exception when it mobilizes its omnipotence.”58 But the Québécois, ils s’en câlissent. Temporary as it may have been, the people, le peuple, had asserted their supremacy over the law that the power wielded to oppress them. As with the injunctions, so with loi 78: “You may well vote a law, we are still here,” they declared.59 And Québec belongs to us.

#22mai: Arrest us all, if you can

The government had moved to assert its authority, and in response, the people had rendered its largest city ungovernable — its authority, a fantasy. All across society, people were mobilizing, as civil disobedience campaigns proliferated under various forms. Citizens overwhelmed the SPVM’s phone lines with phony requests for protest approvals, outlining to the police their plans for a picnic in the park or a birthday party with more than fifty invitees. Global hacktivists Anonymous published the email addresses of SPVM officers. Public figures and celebrities lined up to condemn the historic affront against civil liberties, and the social media sphere was overloaded with an endless train of citizen outbursts that increasingly drowned the mainstream media into irrelevance.

Meanwhile, the CLASSE had broken their silence after they convoked a press conference on May 21 to lay out their response to Bill 78. The congress, declared the spokespersons, had voted to declare the emperor naked: The students would disobey. The CLASSE announced they were launching a website to invite all Quebecers to express their defiance, where thousands uploaded photos of themselves above a sign that held their name, along with a simple message: “I disobey.” “Arrest us all if you can” read the site’s header, “for your law provides even for the crime of opinion.”60 It was a symbolic act steeped in the traditions of civil disobedience: The strike would refuse to acknowledge the government, just as the government had refused to acknowledge the strike.61 But more than contenting themselves with symbols alone, the gauntlet thrown down by the CLASSE had paved the way for a collective tsunami the likes of which the country had never seen.

The next day was May 22, the date of the third national march and the hundredth day since the strike had begun. Dared by the unprecedented government crackdown that lingered over the heads of protesters, the students were more determined than ever to issue Charest his final rebuke, one to match brinkmanship with brinkmanship and launch a deafening riposte fit for the historic moment. The protest call was to mark “100 days of striking, 100 days of contempt, 100 days of resistance,” and the crowds did not disappoint. When the day arrived, upwards of 250,000 marchers flooded the streets for a third time running, giving renewed form to an epic revolt that showed no signs of abating. In a daring swipe at the emergency law, the CLASSE contingent led the crowds as they diverged from the route submitted to police by the establishment student federations, who joined the union leaderships in trying to contain the marchers on the authorized path.62 To no avail. Whether most knew it or not at the time, the May 22 marchers had thus been cast in the largest act of civil disobedience in the country’s history, and the police could do nothing but stand idly by as the human tide swept past.63

#casseroles: After the winter, society stirs

The jubilation that followed from the victory of the street over the state was short lived, and it wasn’t long before the raw dynamics of power had reestablished themselves in the streets of Montréal. The very night of the May 22 march, the SPVM savagely charged the night demonstration as if only to reassert their lost command, sparking a riot that ended in 113 arrests.64 The day had been a joyous if brief respite from the violence that pursued its frenetic race to the brink, each day bringing with it the irrepressible fear of a first casualty. Yet concurrently, in the background at first, a profound mutation of the movement had set root that seemed to flow from the street’s latent desire to pull back from the edge, to avert the worst, and yet at the same time ne pas lâcher — to not back down. But where do we go from here?

The answer was whispered online on the evening of May 17, as Bill 78 was sparking fiery debate in the Assemblée nationale and online. Infuriated by the unprecedented drift to authoritarianism he saw unfolding, François-Olivier Chené, a CEGEP professor of political science, launched a call over Facebook and Twitter for a new form of protest unknown to Québec. Inspired by the cacerolazos that emerged under Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile, Chené summoned Quebecers out onto their balconies, urging them to get out their pots and pans and “bang them with all the rage” that the loi spéciale inspired in them. “I threw the bottle into the sea,” Chené later told Le Devoir, “without knowing whether anyone would take up the call.”65 But that, it seemed, was all it took. Immediately, the #casseroles hashtag he launched snowballed out across social media, going viral.

In the days that followed, every night at eight o’clock, people began emerging onto the balconies that line Montréal’s streets, their kitchenware held at the ready. They were heard first in Villeray, the Plateau Mont-Royal, Rosemont, and soon Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, Saint-Henri, Mile-End, Parc-Extension — the neighbourhoods of the city were springing to life with the sounds of rebellion, as there, surrounded by neighbours on all sides and the security of their homes, their indignation rang out in a collective cacophony that resounded throughout the nights.66 The contagion swept through the city, and by May 20 the casseroles descended from their balconies to begin marching illegally through their neighbourhoods, in improvised processions that grew in size as residents came down from their homes, pots and utensils in hand, to melt into the parades.67 The public spaces of the city — street corners, church lawns and squares across each and every borough — were animated as never before. With no routes or organizers to speak of, the multitudes of marches merged when they met, forming ever larger contingents of tens of thousands as they wound their way endlessly through the streets.68 “On s’en câlisse … clac clac, clac clac clac … la loi spéciale … clac clac, clac clac clac.” Before long, it seemed no block was silent, no street deserted by the chorus of the people’s percussion, as in some neighbourhoods, the church bells in the “city of a thousand bell towers” tolled at eight o’clock to salute the non-violent resistance.69

The CLASSE holds a press conference on May 21, 2012, to announce that they will defy Bill 78.

The sleepy suburbs ringing Montréal — Longueuil, Saint-Basil-Le-Grand, Saint-Eustache, La Prairie — joined in next, as the tidal wave rippled out across the far reaches of the province: Sherbrooke, Trois-Rivières, Gatineau, Granby, Québec City, Saguenay, Saint-Jérome, and on it went. Where the population had been bitterly divided over the students’ protests, suddenly, citizens of all ages and backgrounds were coming together to defend the people’s democratic rights, as the protests spread to at least fifty-five municipalities all across Québec.70 In Montréal, rare was the neighbour who didn’t smile at the sight of pots and spoons hanging from restless hands or of the giddy energy in the eyes of the passersby that carried them. As the casseroles unfurled across Québec to purge society’s sense of collective disempowerment, an infectious and jubilant catharsis aired that once unleashed, proved impossible to contain. Neither Montréal nor Canada had ever seen a mass rebellion like this — an eruption so popular, so spontaneous, so purely and utterly spectacular. Bolstered by the wind of revolt at its back, the movement dared to start believing in its power to topple the government. And proud Montréal, forever irreverent, became an icon of “insubmission” that inspired the collective imagination with “the image of what an entire city in resistance could be like.”71 The affective force of those nightly happenings moved more than a few who’d grown cynical over the years. For while Canada slept, stuck in the mud of its Thatcherite atomization, Québec, all of a sudden, had sprung to life.

The casseroles movement transformed the mobilization by broadening the accessibility and appeal of revolt. In promising a festive ambiance free of police repression, the movement was able to reach into villages and communities, across age and social stratums — “neighbours and people from local businesses, families with small children, elderly and retired people, working adults” — that until then had remained relatively untouched by the unrest.72 It allowed the rebellion to reach into people’s homes and communities where they were and to roll them out the welcome mat lined with assurances of safety and solidarity. And when that happened, it changed everything. Charest had misjudged, quite monumentally it seemed, the depth and breadth of Quebecers’ opposition to his rule, and in trying to suppress a revolt, he had sparked its widest and most determined expansion. Yet in an irony of history, Charest can perhaps find succour in his contributions to the student spring, for in an age of debilitating cynicism and political disaffection, he had unwittingly achieved the unimaginable: the repoliticization of the masses. One citizen’s letter to Le Devoir attempted to capture the essence of the transformation.

A fresh breeze is blowing through the streets of Montréal: Neighbours see each other.[…]Encounters, discussions and evening gatherings now arise casually among neighbours on the porches and balconies of Montréal. The neighbourhood will be less and less foreign. Now that is a true political victory!

We must repeat this pleasant percussion [tapage sympathique], eventually through other forms, until the whole territory is occupied by neighbours who acknowledge each other, who speak to each other, who see each other through the chance encounters of their days and get to know each other over the years. That is how we inhabit a space; that is how we become citizens.

My heart is bursting with joy.73

Or take this one perhaps, from the anonymous administrator of the citizen website Translating the Printemps érable, created out of frustration with the English-language media’s ferociously biased reporting of the student spring. The letter was addressed “to mainstream media”:

I have lived in my neighbourhood for five years now, and this is the most I have ever felt a part of the community; the lasting impact that these protests will have on how people relate to each other in the city is deep and incredible. […] I come home from these protests euphoric. The first night I returned, I sat down on my couch and I burst into tears, as the act of resisting, loudly, with my neighbours, so joyfully, had released so much tension that I had been carrying around with me, fearing our government, fearing arrest, fearing for the future. I felt lighter.[…]

This is what Quebec looks like right now. Every night is tear gas and riot cops, but it is also joy, laughter, kindness, togetherness and beautiful music. Our hearts are bursting. We are so proud of each other; of the spirit of Quebec and its people; of our ability to resist, and our ability to collaborate.

Why aren’t you writing about this? Does joy not sell as well as violence? Does collaboration not sell as well as confrontation? You can have your cynicism; our revolution is sincere.74

In a profoundly charged and consequential sense, the casseroles movement had marked the consummation of the Québécois spring, and the blossoming of the communalist currents that lay embedded within its roots. Beyond the fight over tuition, beyond the confrontation between a government and the youth, the Printemps érable had become nothing less than the invitation to a deep-seated process of rebirth: a re-learning of community, a re-learning of popular sovereignty — indeed, a re-learning, in the most fundamental sense, of what politics means and can be made to mean again. In the wake of the casseroles, citizens began organizing in their communities to form neighbourhood assemblies they dubbed the Assemblées populaires autonomes de quartier (APAQ), in a direct echo of the horizontal and participative assemblies born of the Indignados and Occupy movements and of the 2001 Argentine crisis before them. In boroughs across Montréal, small flyers appeared summoning neighbours to an “egalitarian, non-racist and non-sexist” public forum to decide on the community’s response to the political and police repression.75 The assemblies, which spread outside Montréal to Laval, Longueuil, Saint-Jérome and Trois-Rivières, ultimately failed to attract significant numbers, and most faded away after the 2012 election, although some do remain active in the boroughs of Villeray, Rosemont-Petite-Patrie and Hochelaga-Maisonneuve.76 Yet their first appearance in the Québec landscape itself spoke to the democratic effervescence born of the casseroles, and to the thirst at the roots of society that was all too briefly assuaged in those early days of summer. Faced with the aging heirs of the Thatcherite revolution who had radically reimagined human collectivities as mere agglomerations of individuals “empty of all sociality,”77 masses of Quebecers stood up, at last ready to respond: There is such thing as society, and it is awake.

“Montréal, rebel city”:

The Printemps érable becomes a global sensation

The crackdown sounded by Bill 78, and the casseroles movement that rose up to meet it, hadn’t only transformed the struggle at home. In the wake of the spectacular wave of civil disobedience that washed over the province, the rousing tale of the populist revolt shot onto television screens and the front pages of publications around the world. The story of the Printemps érable had gone global, aided in no small part by the cultural ambassadors of Québec’s rising generation who popularized the cause overseas. Québec’s cinematic wunderkind Xavier Dolan and his full cast of Laurence Anyways graced the red carpet at Cannes with the red square pinned prominently to their clothes. Arcade Fire caused a stir when they sported the emblem in a performance on Saturday Night Live. Across social media, word was spreading of Québec’s peaceful resistance, as for a rare time the international media turned their eyes to the small nation of Québec.

In France, where the student strike had frequently graced the front pages, pop culture magazine Les Inrocks launched a special edition devoted to the “Printemps érable: the coolest revolt.” (Where we learn, for example, that GND apparently wears the same sunglasses as Canadian actor Ryan Gosling in Drive.) And in the Courrier International — owned by prestigious daily Le Monde, which devoted a full dossier on its website to the student crisis — a front-page feature appeared with a photo of a fiery young carré rouge marching in the maNUfestation, the sides of her head shaved as only square patches of red tape covered her breasts. “How the ‘printemps érable’ woke up Québec,” announced the teaser, above the bold headline: “Montréal: rebel city.” From the United States, Australia and Indonesia to China, Russia, the Middle East and countries across Europe, dozens of publications across the world were watching as Québec’s student crisis-turned-democratic uprising pursued its dramatic course. And the carrés rouges only had Charest to thank for their sudden celebrity.78

In the wake of Charest’s loi spéciale, the peaceful resistance of this people of eight million had suddenly become an international cause célèbre. In the week after Bill 78 was passed, Chilean academics and student leaders, who had been protesting for free university education since 2011 in an eerie precursor to the movement of the carrés rouges, penned a rousing letter of solidarity under the header “¡Todos somos quebecenses!” (“We are all Quebecers!”) Excitedly posted online and diffused on Twitter by Occupy Wall Street, the open letter linked together both people’s fights against austerity and the commercialization of public education, and declared: “The struggle of students, academics and workers in Québéc is also our struggle.”79

The sounds of solidarity soon resounded too with the clings and clangs of casseroles protests that emerged in countries around the world. As early as May 21, dozens of demonstrators gathered outside the Québec government’s offices in New York City to protest against Bill 78, and for the first time since the student strike began, a whisper of protest briefly filtered out beyond Québec’s borders to the Canadian provinces.80 On May 30, “Casseroles Night in Canada,” launched on Facebook by Montréal activist and journalist Ethan Cox, saw citizens bang pots and pans in cities across the country, drawing two thousand marchers in Toronto in their bid to channel the communitarian currents of the casseroles and echo the Québec students’ struggle against austerity.81 That same week, images swam through social media depicting cooking utensils and pots and pans held up in protest against the iconic backdrops of the world’s great cities — 150 demonstrated outside Canada House in London’s Trafalgar Square, a few hundred more in front of the Eiffel Tower and some more for a second time in New York, this time in Times Square.82 On June 14, no fewer than seventy cities around the world joined the wave for an international day of action, as small casseroles protests rippled out across all continents, from Montevideo to Zagreb to Honolulu, to launch a powerful condemnation of the Québec government’s descent into authoritarianism.83 The most globally networked generation to ever exist had summoned its friends overseas, and they answered with a force to match the crash of the world catapulting into the social media age. The symbolism of the solidarity blowing in from abroad arrived as a gust of warm wind at the movement’s back. And it arrived as well as a potent signal of the new interplay between distant events that is already redefining the world: On August 4, after the Chilean government banned protests on Santiago’s main avenue, the cacerolazos, fallen silent for thirty years, rang out anew in the neighbourhoods of the capital.84

Formula One versus the people:

The high costs of a commercial state

With the knife of Bill 78 held to the student movement’s throat, the government opened a final round of negotiations on May 28. Four days later, education minister Michelle Courchesne unilaterally broke off the talks (or was perhaps ordered to) and accused the students — who were interested in pursuing the discussions, which they viewed as constructive — of intransigence.85 Charest had appeared at the negotiating table only once, on May 29, sitting down with the students for the first time since the start of the strike in February. He was present for just over thirty minutes, and simply pronounced the gap between the two sides too great to be overcome. Of this anyway he was perhaps correct: The government’s final offer proposed to reduce the tuition increase in the first year to $100 — to be offset through equivalent reductions in tax credits — while the full increase for the six subsequent years would be entirely maintained, for a total increase of $1,624: one dollar less than the exact sum of the five-year hike as initially announced.86

The unconvincing show of Charest’s last best effort set the stage for the final wave of repression, with the security state hiting its apogee as the Canadian Grand Prix arrived in town in early June. The heavily subsidized Canadian Formula One event — whose global boss, billionaire Bernie Ecclestone, is currently on trial and facing ten years in prison for bribing a jailed banker, says Ecclestone, to buy his silence over his tax affairs87 — enjoys the steel-plated backing of the establishment, who vaunt its supposed economic spinoffs. It is also, however, a regular magnet for environmentalist, feminist and left-wing protesters who object to its brazenly anachronistic fetishization of car culture, shameless objectification of women (with its scantily clad playmates) and destructive materialism (just for starters).

After breaking off the final round of negotiations, Minister Courchesne accused Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois of threatening to disrupt the event, after he reportedly told her “With this offer [from the government], we’ll organize your Grand Prix for you.”88 The hysteria from the political and media establishment was immediate and preceded even the student leader’s forthcoming clarifications: that the CLASSE aimed to take advantage of the opportunity to raise awareness of the struggle among tourists, but not to prevent its happening.89 Even the presidents of the FEUQ and FECQ, who frequently part ways with the CLASSE on tactics, were bewildered by the government’s overreaction: “From what I know,” said Martine Desjardins, “the CLASSE simply has the intention to inform people, to go distribute red squares and raise awareness about the issues.”90 A simple call to the student associations would have allowed them to offer reassurance, added Desjardins. Yet given the virulence of the government’s indignation, Quebecers would have been forgiven for thinking the CLASSE had threatened to set off a bomb.

It may be that the government was genuinely terrified at the thought of so lucrative an event being compromised; or it may be that Charest smelled another tactical opportunity to tar the CLASSE as violent, and pounced, with the media and economic establishments only too eager to board the bandwagon. Either way, the F1 immediately announced it was “preventatively” cancelling the Grand Prix Open House out of concerns for the safety of attendants, thereby dutifully validating and amplifying the government attack line. With the supposed threats of the CLASSE inflated enough to serve as effective cover, the police then leapt into a state of paranoid delirium to defend the perceived commercial interests at risk. A call was sent out for protesters to swarm and jam the metro line leading to Parc Jean-Drapeau, which is situated on Île Sainte-Hélène. The SPVM reacted by stationing three officers in each metro car and launching an unprecedented campaign of blanket political profiling. Illegal searches and seizures targeted anyone sporting the red square or “any youth not fitting the aesthetic canon of the F1 fan.”91 One art student carrying red paint in his bag was thus deemed suspect and expelled from the metro; one person carrying juggling balls too, in a city that’s a global hub for circus arts; and without a trace of irony, one woman was detained for reading 1984 on the metro.92

Rampant cases of “preventative arrests” aimed at those matching the police’s stereotypes inflamed social media and drew pointed interventions by legal experts who decried the unqualified illegality of such tactics.93 There exists no concept of preventative arrests under Canadian law, even if that hasn’t stopped Canadian police from increasingly cracking down on protests by invoking Article 31 of the Criminal Code, which was designed to combat proven or imminent violations of the peace. The courts have been called on to pronounce on this trend in at least three cases (all since the 1980s), with the most notable and recent delivered in 2011 by an Ontario provincial court judge in response to their widespread use during the G20 Summit in Toronto.94 In all cases, the courts ruled that Article 31’s invocation was invalid and abusive without a specifically identifiable, imminent and substantial threat. In the G20 case, the judge’s scathing indictment of the “adrenalized” police force left no room for doubt, condemning the aggressive tactics as amounting to the “criminalization of dissent.”95 The troubling conclusion is that those deciding the priorities of the SPVM would seem too preoccupied with expanding their arsenal against their own citizens to bother teaching the law to those we empower to enforce it.

The SPVM erected an open-air triage and detention facility near the Biosphère outside the Parc Jean-Drapeau metro station, which it used to process and hold dozens of innocent youth who arrived on the island that also plays host to a plethora of recreational facilities. Accounts surfaced of people who were held for up to three or four hours without access to water or toilets, their hands cuffed or tie-wrapped, before being released without charges at the Angrignon metro terminal located at the opposite end of town.96 Yet embarrassingly for the SPVM, two such “carrés rouges,” who were instantly swarmed by sixteen police officers and detained upon exiting the metro, were no ordinary backers of the movement, if indeed they were at all. They would later discover, in fact, that they were undercover journalists for Le Devoir.97 The next morning, the newspaper’s front page screamed “Carrés rouges, your documents!” above an explosive report that tore to shreads the SPVM’s claims to be basing its interventions solely on suspicious comportment.98 The image traced by the journalists was of a bellicose and vigilante police force that was devoted to protecting the Grand Prix from all signs of dissent, and that dripped with explicit contempt for students, as well as for legal and constitutional guarantees.

The journalists cooperate, but return a question for each one posed [by police]. Why search us? “Because you’re adorning revolutionary insignia,” answers an officer, “and because I’ve had it with people like you.” He’s wearing a gauze on his forearm, which seems to protect an injury. But isn’t this profiling? “We’re doing exactly that, criminal profiling,” responds the same officer. Is Parc Jean-Drapeau no longer a public place? “Today, it’s a private place open to the public,” adds another, removing from our bags a mango, a dance season program, notebooks, pens. Nothing illegal, nothing that hints at any criminal intentions. Why can’t we be here? “The organizers don’t want you here.” So today, the SPVM responds to the needs and desires of Grand Prix organizers? “Exactly,” says officer 5323, proudly repeating it a second time after we ask again. At the request of the journalists, the two main officers provide their badge numbers, insisting that we write them down. “Take them, your notes, for the ethics complaints board and all that. You can call my boss, Mister [Commander Alain] Simoneau, he’ll be happy to hear you say I’m doing a good job.”99

The journalists were held at the outdoor detention facility for questioning and accused by the police, without any explanations, of holding “criminal intentions.” It was only after providing their identification — and thus being revealed as journalists — that Catherine Lalonde and Raphaël Dallaire Ferland were released without charge but expelled from the island, in the company of a photographer they’d encountered whose photos were deleted by police without his consent.100 At least forty-three people were “preventatively” arrested that day.101

At the second event site downtown, Charest’s beloved Grand Prix couldn’t escape the unrest that was smouldering in the streets. Society encroached from all sides. Summoned by the lately emboldened Convergence des luttes anticapitalistes (CLAC), masses of angry protesters, enraged by the indecency of the excess being flaunted in the midst of Liberal austerity, descended on the event as never before. The party strip became a battleground, as the security apparatus was mobilized to protect Crescent Street’s consumerist bubble and prevent tourists from having to encounter a whiff of the crisis into which they’d breezily plunged. At a busy downtown intersection, peaceful protesters trying to enter the barricaded street were ferociously repelled by lines of armed riot police, liberally pepper-sprayed, beaten with batons and dragged across the pavement, in full view of bar patrons who looked on from the overflowing terrasses.102 Police launched targeted arrests of people guilty of no more than wearing black or of sporting communist insignia, which in the eyes of police commander Alain Simoneau constituted a “clear” source of danger.103 Some protesters had managed to infiltrate the site and were sharply expelled after erupting inside with chants of “Travaille, consomme pis ferme ta gueule!” (“Work, consume and shut your mouth!”)104 Yet mostly, the decibel-rattling dance music insulated the tourists’ sunny afternoons from the raging crisis around them, as faintly in the distance, the seething popular anger struggled to pierce through the sonic fog: “1-2-3-4, this is fucking class war! 5-6-7-8, overthrow this fascist state!”105 The partiers, protected by the state, were free to spend to their heart’s content, unperturbed and in perfect calm, as a part of Québec’s embattled democracy was writhing in pain a few metres away.

Government rhetoric persisted in its well-rehearsed hysteria through the summer, as the eerily robotic coherence of ministers’ statements seemed to confirm suspicions of a meticulously choreographed Liberal strategy. The government script had scarcely changed since the start, though minister of culture Christine St-Pierre slipped into an apparent excess of zeal when she claimed the red square worn by a respected writer simply symbolized “violence and intimidation.” The farcical attack, however, had grown increasingly strained with time. By then, it was being worn by an important cross-section of Québécois society that included Opposition leader Pauline Marois, artists, professors, progressives and parents of all backgrounds, and some of Québec’s most lauded celebrities in high-profile international appearances. Her smear proved especially incendiary because of its context: It was uttered in response to author Fred Pellerin temporarily refusing his appointment as Knight of the Ordre national du Québec, explaining that such honours seemed inappropriate to him in the midst of a social crisis. St-Pierre’s reaction sparked outrage in the cultural community, and 2,600 artists signed an open letter demanding an immediate apology. It came late, but did eventually arrive.106

Thirty-five days to fix the world

St-Pierre’s comments were not only ill-advised, but equally ill-timed. In the greater scheme, the movement was pursuing its mutation away from street confrontations with police and toward the casseroles’ family-friendly tapage. Such was the scenario leading into the vacation months, as the marches dwindled in size leading into an August electoral campaign. On August 1, however, the same day as Charest had convoked the election, one final show of strength and defiance was launched by the street across the premier’s bow. That day also fell on the one hundredth day since the start of the nightly marches. After weeks of relative calm and shrinking nightly crowds, one last hurrah drew thousands into the streets, as casseroles marches departed from their neighbourhoods to converge downtown in “a long and joyous procession,” to chants of “Les élections, on s’en câlisse!”107 Invoking the “silent majority,” Charest called the election for September 4 to settle the crisis once and for all, and framed the issue facing voters thus: “In Québec, is it the street that governs? […] Or will it be employment, the economy and democracy?”108

The FEUQ and FECQ promised to meet him on his path, and Léo Bureau-Blouin, replaced at the head of the FECQ by Éliane Laberge in June, declared his candidacy for Pauline Marois’s Parti Québécois.109 The federations embarked on a provincial tour to prevent the re-election of the Liberals, while the CLASSE launched its own to promote its newly released manifesto, Nous sommes avenir. And as for Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois: He bowed out of the spotlight on August 9 after issuing his resignation, delivered in the form of an eloquently unmistakable “à la prochaine” that was published in Le Devoir. With the precise mordancy that has become his trait, GND’s moving appeal reverberated with a generation’s dream of a democratic future and landed as a gauntlet thrown down at the feet of the governing élites.

The solidarities sewn across clouds of gas will not soon be undone. The outstretched hands will not release. And we will march again, for years if we must and well beyond this strike, so that one day the people of Québec may take back the reins of this country from the hands of money and the profiteers.110

The saga of the Printemps érable needed an election to resolve the immediate question of the tuition increase, and certainly, to restore the social peace. But the forces and ambitions that grew to full form during the student spring will not turn back and retreat into obscurity. One chapter closes only to prepare the way for the next. For there can be little doubt that Nadeau-Dubois speaks for countless others when he evokes the readiness of the youth to pursue the long march, and who feel, quite as he does, that le combat est à venir — the struggle has just begun.