H. L. Hunt’s private life was equally notorious: He had six children with his first wife, Lyda Bunker, including Nelson Bunker, Lamar, and William Herbert. Later, he started an affair with Frania Tye, whom he married and with whom he had four children before the couple separated in 1942. Hunt had another four children with one of his secretaries, Ruth Ray, whom he finally married in 1957.

Unlike the Rockefellers, whose surname has always been associated with wealth, crude oil, and the Standard Oil Company, the name Hunt is forever tied to the largest failed speculation in silver.

A Precious Metal Primer—A Recap

The two most significant factors in the past 50 years for precious metals have been the prohibition of private gold holdings in the United States and the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, which was created in 1944. In 1933 President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared private possession of gold of more than 100 USD illegal, and the ban remained in place for more than 40 years. With the Nixon Shock of 1971, the United States declared an end to the official convertibility of the US dollar into gold, due to massive increases of government debt, expansion of the money supply, and rising inflation. In 1973 the Bretton Woods system—the international currency system that established the US dollar as the leading currency, backed by gold (“the Gold Standard”)—fell apart. With the abolition of the silver and gold standards, both metals lost their economic importance, and large quantities became available on the market. As a result, silver fell to 2 USD per troy ounce. But this price level also has had a lasting negative effect on silver production, as only a few countries are able to produce it at this low price level.

William Herbert and Nelson Bunker Hunt were the first big investors to recognize the rare opportunities offered by the silver market in the 1970s: There was constant industrial demand, low incentives for subsidies due to low prices, and a small market of available silver.

Nelson Bunker had made no secret of his aversion to “paper money” after the gold standard was abandoned. “Every moron could buy a printing press, and everything might be better than paper money,” he said. To preserve the family fortune, the Hunt brothers focused their investments on real estate and the silver market.

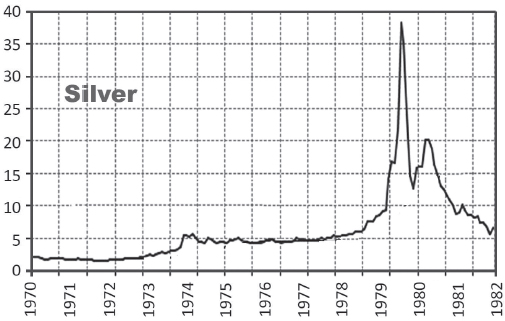

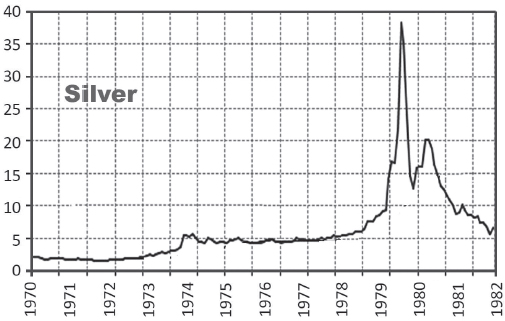

Between 1970 and 1973 Nelson Bunker and William Herbert bought about 200,000 troy ounces of silver. Within these three years, the price of silver doubled from 1.5 USD to 3 USD per troy ounce.

Encouraged by this success, the brothers expanded their activities to futures exchanges and acquired, at the beginning of 1974, futures contracts representing 55 million ounces of silver. Then they waited for physical delivery. Physical delivery was as unusual at that time as it is nowadays, and with constant purchases on the spot markets, the Hunts generated an artificial shortage of silver. Keeping in mind how the United States had appropriated private gold holdings 40 years before, they had the bulk of the precious metal delivered to banks in Zurich and London, where they thought their silver stocks would be safe from US authorities.

This was equivalent to half of US silver reserves, about 15 percent of the world’s total. In addition, the Hunt brothers possessed around 200 million ounces of silver in the form of exchange-traded futures contracts. Global demand for silver rose to around 450 million ounces, while output remained below 250 million ounces, due to the low price level of just a few years earlier.

In the meantime, the price of silver had risen to 8 USD, then it doubled to 16 USD in just two months, due to a growing physical shortage of silver. The CBOT and COMEX combined were able to deliver only 120 million ounces of silver, since the Hunts’ strategy concerning physical delivery was now being imitated by an increasing number of market participants.

Figure 8. Silver prices, 1970–1982, in USD/troy ounce. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

At the end of 1979 the price of silver rose to 34.50 USD; in the middle of January 1980 the price jumped above 50 USD (about 120 USD in today’s prices). The Hunt family’s silver stocks surpassed 4.5 billion USD in value!

The wheel of fortune was about to turn, however. Once COMEX accepted only liquidation orders, prices started to fall. The US Federal Reserve System increased interest rates, and the stronger US dollar began to negatively affect prices for gold and silver. By mid-March 1980, silver prices had fallen to 21 USD. The crash was accelerated by panic selling on the part of smaller speculators who had followed the Hunts’ example. Others cashed in private silver stocks of jewelry and coins because of the record prices, further increasing physical supply of the metal.

As March 1980 came to an end, the Hunts could no longer meet the margin requirements of their futures positions and were forced to sell more than 100 million USD worth of silver. On March 27, 1980, silver opened at 15.80 USD and closed at 10.80 USD. The day went down in history as “Silver Thursday.”

For the Hunts, whose volume-weighted average entry price in silver futures was 35 USD, this meant a debt of 1.5 billion dollars!

Many investors, including COMEX officials who held short positions, significantly reinforced the downward spiral in silver prices. Although the metal recovered to about 17 USD by the mid-1980s, the Hunts had to file for bankruptcy and were accused of conspiracy to manipulate the market.

The downfall of the Hunts was caused by extensive leverage. Otherwise they would have been able to weather the crash in silver prices without having to liquidate massive positions in the market. In the media the Hunts became a symbol of market manipulation, and their speculation and the collapse of silver prices, which caused huge losses for private investors, weighed down the reputation of the silver market for decades.

Key Takeaways

•Haroldson Lafayette Hunt, known as “Arkansas Slim,” founded the family fortune on oil. Subsequently the Hunts were among the top 10 wealthiest families in the United States.

•Brothers Nelson Bunker and William Herbert Hunt tried to preserve the family wealth by investing in silver. They attempted to corner the silver market by buying the metal physically and building up large futures contract positions.

•The price of silver skyrocketed from below 2 USD per troy ounce to above 50 in January 1980. By then, the Hunt family fortune surpassed 4.5 billion USD. But on March 27, 1980—“Silver Thursday”—silver crashed 30 percent. The Hunts had to file for bankruptcy and were accused of conspiracy to manipulate the silver market.