15

The Doom of German Metallgesellschaft

1993

Crude oil futures take Metallgesellschaft to the brink of insolvency and almost lead to the largest collapse of a company in Germany since World War II. CEO Heinz Schimmelbusch is responsible for a loss of more than 1 billion USD in 1993.

“We’re back, we’ve made it.”

—Kajo Neukirchen, CEO of MG

He was one of the stars of the German business scene: In 1989 Heinz Schimmelbusch became the youngest CEO in German history, the head of German Metallgesellschaft (MG), a huge industrial conglomerate founded in 1881 with a focus on mining and commodity trading. With Schimmelbusch’s arrival, a new wind was blowing through the company. Its traditional dependence on the metal business, which accounted for almost two-thirds of group sales and profit, was about to be reduced. The new growth areas would be engineering, environmental technology, and financial services.

Schimmelbusch went on a shopping spree, acquiring Feldmühle Nobel, Dynamit Nobel, Buderus, and Cerasiv and creating an empire, valued at 15 billion USD, that included more than 250 subsidiaries. In 1991 Manager Magazine named him “Manager of the Year.” But four years after Schimmelbusch joined MG, his realm would end in disaster.

The subsidiary of the MG Group in the United States was engaged in risky bets on crude oil prices.

Under Schimmelbusch the MG Group was not only getting bigger but also more complicated to manage. At the beginning of the 1990s, the German economy cooled down. There was pressure from cheap Eastern European competitors, the car industry weakened, and Metallgesellschaft’s high debt levels began to drag on the company. But the firm’s Sword of Damocles was actually hovering above its subsidiary in the United States.

Metallgesellschaft Refining and Marketing (MGRM) in New York sold fuel oil, gasoline, and diesel to large customers at long-term fixed rates; the company dealt in contracts of five- to ten-year maturity that promised delivery of a certain quantity of oil at a fixed price every month. MGRM’s customers were hedging against rising crude oil prices. However, MGRM did not have oil through its own sources or inventories. It had to buy the oil itself.

Understanding the Oil Market

From 1984 to 1992, the oil market was dominated by what traders refer to as “backwardation.” This means that price of crude oil to be delivered in the future will be traded at a discount to the current (cash) price. For the buyer of oil contracts this means, in addition to interest gained on the capital invested, there’s a gain from the difference between the future price and the spot price. Thus, MGRM’s rollover hedging strategy generated a continuous profit in addition to its hedging fees.

Due to the volatile price of crude oil, MGRM was facing a market price risk of more than 600 million USD, which corresponded to one-tenth of the balance sheet of the parent company. This market price risk was hedged by futures.

The company entered into a growing volume of crude oil futures whose sizes would be adjusted just before maturity to the contract volume of its customers and which would be rolled forward into the next contract month.

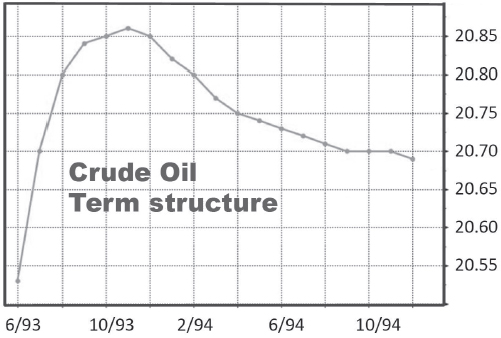

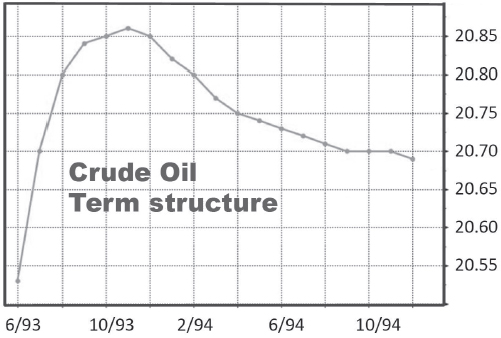

A massive price decline in crude oil flipped the future term structure from backwardation into contango, which resulted in massive losses in MGRM’s hedging strategy.

However, in 1993, these conditions changed as a massive decline in crude oil prices reversed the future term structure from backwardation to “contango,” in which future prices are higher than current ones. While the current oil price was below 18.50 USD per barrel, prices for a year ahead were more than 1 USD per barrel higher. The monthly gain for MGRM was converting into a widening loss. And there was another factor neglected by MGRM: rising cash-flow risks during contract maturity.

While its delivery obligations matched delivery requirements at maturity, MGRM was now faced with increasing margin payments in the future. This had a direct impact on the balance sheet for MGRM, since realized losses would not be offset by potential future profits.

Figure 10. Crude oil future term structure in 1993/1994, in USD/barrel. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

The situation continued to worsen as MGRM suffered from liquidity problems and poor credit ratings. In the context of declining oil prices, MGRM was caught in a vicious circle.

Local management staked everything on a single throw of the dice and continued to carry out additional contracts with customers. At the low point of the crisis, MGRM alone was responsible for between 10 and 20 percent of all outstanding one-month-forward transactions in crude oil.

By terminating all crude oil futures positions, the MG Group realized a loss of more than 1 billion USD.

Meanwhile, German Metallgesellschaft’s fortunes had also been plunging. As a result of the economic slowdown and a high debt burden, the company could only pay a dividend in 1991–1992 by writing down hidden reserves. The following year the deficit had climbed to almost 350 million Deutschmarks, about 200 million USD. Then the bad news from the United States hit. Under pressure from creditors, MGRM was forced to file for bankruptcy with a loss of 1.5 billion USD. That brought the entire group to the brink of insolvency.

In February 1993 Schimmelbusch launched an extensive divestment program to redeem 600 million USD. But the US subsidiary’s losses continued to grow and soon exceeded 1 billion USD. Schimmelbusch now had to ask for additional funding by the company’s major shareholders, Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank. Startled by the imminent loss, Ronaldo Schmitz, a member of Deutsche Bank’s executive board and chairman of MG’s supervisory board, pulled the trigger. The MG Group realized losses of more than 1 billion USD as a result of the termination of all crude oil contracts, and the group’s total liabilities grew to almost 5 billion USD.

On December 17, 1993, Schimmelbusch and CFO Meinhard Forster were dismissed by the supervisory board without notice, and Kajo Neukirchen was hired by Schmitz to save the company. With a bailout of 2 billion USD, rigorous cost savings, and the dismissal of 7,500 employees, Neukirchen restructured the MG Group, which now focused on trading, plant construction, chemicals, and construction technology. In February 2000 the company was renamed MG Technologies, and it became the GEA Group in 2005. The MG Group had met an inglorious end.

Key Takeaways

•CEO Heinz Schimmelbusch became the youngest CEO in Germany when he headed German Metallgesellschaft (MG Group), a large and venerable industrial conglomerate. Manager Magazine named him “Manager of the Year” in 1991.

•MGRM—the company’s crude oil refining and marketing subsidiary—followed practices that would adversely affect the entire conglomerate.

•MGRM was selling petroleum products at a fixed price to customers, hedging its exposure on the futures market. During normal market conditions, the backwardation term structure of crude oil provided a comfortable markup.

•Things changed when crude oil dropped from more than 40 USD in 1991 to below 20 USD in 1993, and the term structure flipped into contango. Losses mounted to a total of more than 1 billion USD and brought the MG Group to the brink of bankruptcy.