Gold: Welcome to the Jungle

1997

In the jungle of Borneo, the Canadian firm Bre-X supposedly finds a gold deposit with a total estimated value of more than 200 billion USD. Large mining companies and Indonesian president Suharto all want a piece of the pie, but in March 1997 the discovery turns out to be the largest gold fraud of all time.

“Geologically, it’s the most brilliant thing I’ve ever seen in my life! It’s so big, it’s scary. It’s f***ing scary!”

—John Felderhof, Bre-X

“This can’t be a scam! Do some more tests! Figure it out! I know it’s there, okay?”

St. Paul is a remote community with roughly 5,000 inhabitants northeast of Alberta, Canada. Its only tourist attraction has been a landing platform for UFOs that was erected on June 3, 1967. In the middle of the 1990s, however, the tiny town became the focus of international media: Every 50th resident was a shareholder of the mining company Bre-X, whose value had increased 500-fold within just three years. As a result, the number of millionaires in St. Paul had suddenly shot up dramatically. At the center of attention was John Kutyn, an employee of the local savings bank, who had sold everything, including his car and his motorcycle, to invest in Bre-X early on.

St. Paul, a small Canadian community of 5,000, recorded a sudden surge in resident millionaires.

Kutyn spread the news about the gold discovery of the century among his neighbors and customers. He would be one of the few who managed to exit the company before it collapsed. A wealthy man, he went on to settle in New Zealand.

In the 1980s Canada had witnessed a boom in exploration companies, which searched the world for crude oil, gold, and other commodities. Among them was Bre-X, founded by former stockbroker David Walsh late in the decade. From an initial 0.30 Canadian dollar (CAD), the value of Bre-X shares fell to a few cents in 1993. But that would change after Walsh and a geologist named Felderhof bought exploration rights for Busang in the jungle of Borneo, Indonesia. Together with his colleague Mike de Guzman, Felderhof had explored Busang for another company in the mid-1980s, and the two men had found small traces of gold. On May 6, 1993, Bre-X announced that it had acquired a license for Busang. At that point the share price was around 0.50 CAD. But drilling samples validated gold levels of more than 6 grams per ton of rock. Since 3 grams are considered an excellent result, this caused a sensation.

Was Busang home to the biggest gold treasure of all time?

In November 1995 Busang’s gold resources were estimated at more than 30 million ounces, and toward the end of the year the stock price of Bre-X shares climbed above 50 CAD! At the annual general shareholders’ meeting in May 1996, the company was valued at 200 CAD per share, which then split by 1:10. The estimates kept rising: Bre-X reported more than 39 million ounces of gold in June 1996, 47 million ounces in July, 57 million ounces in December, and 71 million ounces in February 1997. Shortly afterward, Felderhof publicly speculated about resources of more than 100 million ounces. This would have made Busang the richest gold deposit of all time. Market rumors even doubled the estimate: Some 200 million ounces, about 6,000 tons, were supposed to lie hidden in the jungle of Borneo!

Though the company had not produced a single ounce of gold, Bre-X shares rose 500-fold.

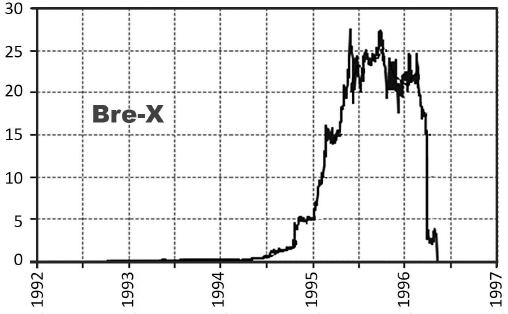

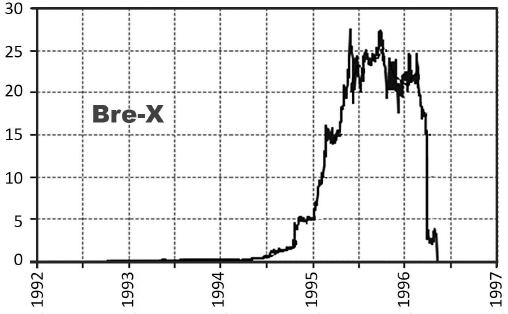

At the beginning of September 1996, the stock reached its highest price—28 CAD (which corresponded to a price of 280 CAD before the stock split) and a market capitalization of more than 4 billion USD. In just three years the value of Bre-X shares had increased by more than 500 times, even though not a single ounce of gold had been commercially produced!

But then things began to fall apart. On March 19, 1997, Mike de Guzman committed suicide by jumping from a helicopter. During the due-diligence process, independent drill holes had revealed only negligible amounts of gold. A week later, lab results showed that Bre-X had manipulated the initial samples. It was a personal disgrace for Peter Munk, the head of Barrick Gold, and the news caused investors to panic. The share price of Bre-X collapsed, and the stock was suspended from trading. Later Bre-X had to declare bankruptcy, and the stock became worthless.

Figure 14. Share price of Bre-X, 1992–1997, in Canadian dollars (CAD). Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

Bre-X crashed. The stock was worthless.

Not everyone suffered. David Walsh capitalized 35 million USD by selling Bre-X shares before the collapse and moved to the Bahamas. John Felderhof was able to sell nearly 3 million Bre-X shares, with a total value of almost 85 million CAD, between April and September 1996. He found a new home in the Cayman Islands. The Bre-X scandal was finally settled in 2002. However, legal disputes continue today.

Key Takeaways

•The Bre-X scandal remains the biggest corporate mining scandal in Canada to date.

•In 1993 David Walsh and John Felderhof claimed to find the gold deposit of the century in Borneo. Their company, Bre-X, rose from a penny stock, trading below 30 Canadian cents, to 4 billion USD in market capitalization. From mid-1993 to mid-1996, the value of Bre-X shares increased by a multiple of 500. Indonesian president Haji Muhammed Suharto and large multinational gold companies all wanted a piece of the pie.

•But in March 1997 the discovery was unmasked as the largest gold fraud of all time. Lab results confirmed that the company had manipulated its gold samples. Bre-X declared bankruptcy; its stock was worthless.