2005

A trader for the Chinese State Reserve Bureau shorts 200,000 tons of copper and hopes for falling prices. However, when copper prices climb to new records, he disappears and his employer pretends never to have heard of him. What sounds like the plot of a thriller shocks metal traders all over the world.

“It’s one thing to have a rogue trader on your staff—that happens. But I’d be amazed if China wanted a reputation as a rogue nation in these markets, where it has become such an important player.”

—Anonymous trader

Most people even have trouble pronouncing the name Liu Qibing, but in November 2005 the Chinese copper trader was the number-one topic of conversation on the commodity futures exchanges in London, New York, and Shanghai. Rumors were circulating about a massive, speculative short position in the copper market: Liu Qibing, in his capacity as a trader for the Chinese State Reserve Bureau (SRB), was said to have shorted futures contracts on the London Metal Exchange (LME) amounting to 100,000 to 200,000 tons.

Unlike Yasuo Hamanaka in Japan almost ten years earlier, Liu Qibing was speculating on falling copper prices. However, prices continued to rise, and the talk of a massive short position temporarily drove London’s three-month-forward copper contracts to a record high of nearly 4,200 USD per metric ton.

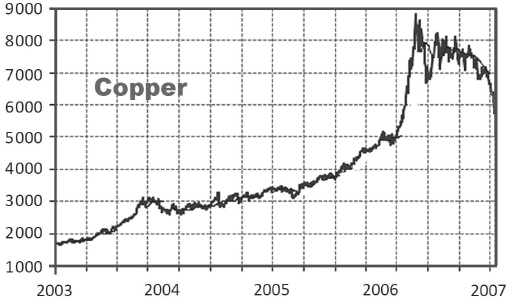

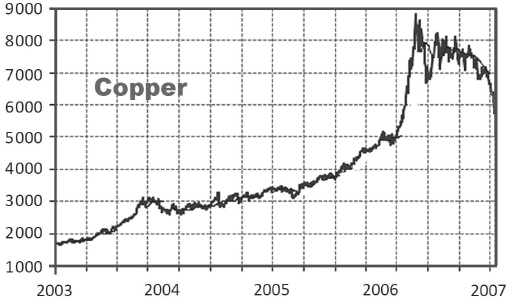

Starting at 1,500 USD, the copper price bounced up to 9,000 USD per ton.

Copper prices had started to climb since the turn of the millennium. In December 2003 the price of copper broke the 2,000 USD per ton mark for the first time, while the average price of previous years was only slightly above 1,500 USD. Just a few months later, the price breached the 4,000 USD level. The trigger for this development lay in the growing demand of the Chinese economy, which required more and more of the red metal for its infrastructure and housing industry. Although the OECD countries (members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) collectively consumed about 80 percent of the world’s copper output at that time, China’s growth was more dynamic. Copper consumption in OECD countries increased on average by 2.5 percent per year over the previous five years. However, China’s demand grew by about 15 percent per year over the same period, while supply growth proved inflexible. At peak times China’s demand growth accounted for more than 80 percent of global demand growth.

China was sucking global copper markets dry.

At that time China alone accounted for a quarter of the world’s copper consumption. Meanwhile, the prices for industrial metals continued to rise, because producers were slow to respond with an increased supply. There were several reasons for their reluctance: First, the development of new mines usually takes several years until the first ton of copper can be produced. Second, many producers didn’t trust the high price level to last and therefore delayed long-term investment projects. By 2004, however, the extension of existing projects and the activation of new mines were entering a decisive phase. Experts—including the world’s largest copper producer, Chilean Codelco, and the Chinese State Reserve Bureau—expected the supply to increase at the end of 2005, and the rise in copper prices should have come to an end. As it turned out, that was a misperception for which China paid dearly.

Contrary to expectations, almost all major producers had problems with production. Costs increased; high oil prices, strikes, and even earthquakes all had a lasting effect. The projected additional supply in the copper market was lagging, and demand, continually fueled by China’s dynamic economic growth, was jumping ahead. As a consequence, the price rose steadily. The rumors surrounding Liu’s positions created additional momentum, as copper inventories on commodity futures exchanges in London, New York, and Shanghai reached their lowest levels in 30 years.

Figure 16. Copper prices in USD/ton, 2003–2007, London Metal Exchange (LME). Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

The newspaper China Daily reported that 130,000 metric tons of copper were sold by Liu Qibing for the SRB at an average price of 3,300 USD per ton. As the price of copper rose above 4,000 USD, Liu broke off contacts with other traders in London and China and disappeared. His cell phone remained silent, the door of his apartment on the 10th floor of a Beijing building never opened, and he was absent from his job in Shanghai.

The Chinese trader broke off all contacts, never answered his cell phone, and his employer denied his existence.

At first Liu’s employer denied he existed. Later, the SRB claimed that the trader was acting solely on his own behalf. The SRB, which was founded in 1953, was supposed to stabilize prices and secure supplies through commodity trading, not earn profits through speculation. Industry experts considered the 36-year-old trader, who was under house arrest according to Chinese sources, more a pawn than a perpetrator.

Liu, the son of a farming family from Hubei Province, had been with the SRB since 1990 and had been trained for futures and options trading at the London Metal Exchange (LME). Between 2002 and 2004, Liu is said to have generated more than 300 million USD in risky copper trades for the SRB. Now, the Chinese state was facing losses of hundreds of millions of dollars. In response, the government in Beijing tried to push down the world market price through copper auctions. In a first tranche, 50,000 tons were sold. Another tranche of a similar size was to follow, and the leadership in Beijing spread the word that the country had 1.3 million tons of copper in reserve. However, market participants estimated that the amount of copper available was just half that. The Chinese government’s actions were unsuccessful, as more and more market participants took counter-positions to force China to make physical delivery of the metal in late December.

Hedge funds—called “crocodiles” in China—particularly saw an opportunity to generate short-term profits. The copper price climbed above 5,000 USD in January 2006, to 6,000 USD in early April, and to 7,000 USD at the end of that month. It rose to the dizzying heights of nearly 8,800 USD a ton in May, before normalizing again over the coming months.

Key Takeaways

•Like the Japanese trader Yasuo Hamanaka almost 10 years before, Chinese trader Liu Qibing was caught on the wrong side of the copper market. He speculated on falling prices and lost a great deal.

•Liu was working for the Chinese State Reserve Bureau (SRB), which handled the Chinese economy’s rising demand for the commodity. Market intelligence estimated Liu’s short position at about 100,000 to 200,000 tons of copper.

•Copper prices climbed from 1,500 USD per ton in 2003 to almost 9,000 USD in 2006, and Liu, labeled as a rogue trader, vanished.