Zinc: Flotsam and Jetsam

2005

The city of New Orleans, called The Big Easy, is well known for its jazz, Mardi Gras, and Creole cuisine. Less well known, however, is that about one-quarter of the world’s zinc inventories are stored there. Hurricane Katrina’s flooding makes the metal inaccessible, and concerns over damage cause the price of zinc to rise to an all-time high.

“It’s totally wiped out . . . it’s devastating.”

—President George W. Bush

Even though global inventories continued to decline, many producing companies remained skeptical about increasing the supply. “At this point, nobody in our business is rushing to build new zinc mines,” explained Greig Gailey, managing director of Zinifex, the world’s third-largest producer of zinc (after Xstrata and Teck Cominco), in 2005. “We’re certainly not, nor are Teck Cominco or Falconbridge.”

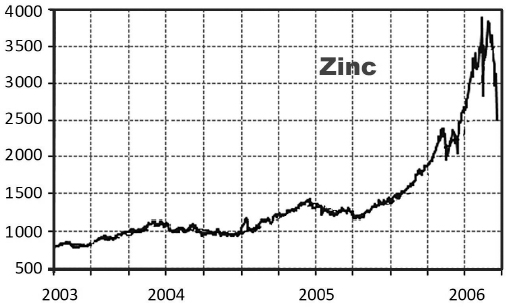

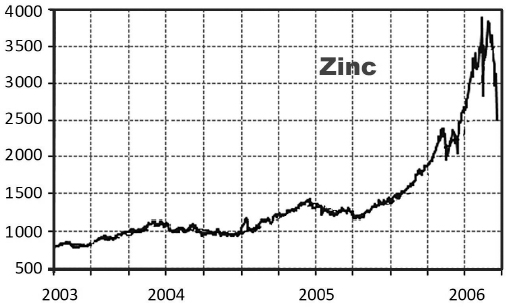

Figure 17. Zinc prices in USD/ton, 2003–2006, London Metal Exchange (LME). Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

By this time the price of zinc was hovering around 1,200 USD per metric ton. It had broken through 1,000 USD at the beginning of 2004, after moving in a narrow range between 750 and 850 USD over the two previous years.

In a nutshell, that was the situation until August 2005. Then Katrina hit New Orleans like an atomic bomb. The Level 5 hurricane caused devastating damage in the southeastern United States but particularly affected the city, whose urban area was almost completely below sea level.

Twenty-four official LME warehouses had been sited in and around the city at the Mississippi Delta, due to its geographical location and attractive economic conditions. In addition to 250,000 tons of zinc, there were also 1,200 tons of aluminum and 900 tons of copper locked away. Global zinc inventories were estimated by the International Lead & Zinc Study Group to be just over 1 million metric tons at that point—the equivalent to a 35-day global supply. The inventories in New Orleans therefore accounted for around a quarter of global stocks and about half of the zinc traded at the LME. Due to the flood damage in New Orleans, however, access to the zinc was suddenly severely limited.

Stephen Briggs, a metal analyst at Société Générale, summarized the situation: “We have a potentially serious development . . . the market is assuming that the metal is damaged and will be inaccessible for a lengthy period of time.”

Who Needs Zinc?

Zinc is mainly used as corrosion protection for other metals or metallic alloys such as iron or steel, and most of the demand for it is based on infrastructure, construction, and transport. Zinc is commonly produced as a co-product with lead, and worldwide mined production is around 11 million metric tons. The largest producer countries are China, Australia, Peru, the United States, Australia, and Canada; the latter two are also the largest exporters of the metal. Unlike the more concentrated markets for copper or nickel, the 10 largest companies produce less than 50 percent of the world’s zinc.

At the end of the year, zinc prices broke through 1,900 USD and, just under two weeks later, reached 2,400 USD in London. But that was only the beginning: The worsening situation eventually drove the value of the metal to 4,000 USD in the first half of 2006 and marked a new high of just under 4,600 USD per ton in November of that year.

By 2007 the scare was over: Beginning in August, the price dropped continuously over the next 12 months, from 3,500 USD to less than 1,500 USD.

Key Takeaways

•Only market insiders were aware that warehouses in the city of New Orleans held around a quarter of global zinc stocks and about half of the zinc traded at the London Metal Exchange, the biggest physical metal market in the world.

•In August 2005 Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, causing extensive flooding in the area and making zinc inventories inaccessible.