22

Natural Gas: Brian Hunter and the Downfall of Amaranth

2006

In the aftermath of the closure of MotherRock, an energy-based hedge fund, the bust of Amaranth Advisors shakes the financial industry, as it is the largest hedge fund failure since the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998. The cause? A failed speculation in US natural gas futures. Brian Hunter, an energy trader at Amaranth, loses 6 billion USD within weeks.

“The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

—John Maynard Keynes

The news shook financial markets like an earthquake in September 2006: Amaranth Advisors, a 10 billion USD American hedge fund, erased around two-thirds of its capital in two weeks by betting on natural gas and was about to close. Only a few weeks before, MotherRock, another hedge fund that specialized in natural gas futures, had collapsed as well. Some of the causes for these events date back to previous years. Following the record hurricane seasons of 2004 and 2005, many hedge funds had become interested in the energy markets. Hurricanes Ivan, Katrina, Rita, and Wilma had all damaged crude oil and natural gas production facilities in the Gulf of Mexico, resulting in a significantly reduced supply.

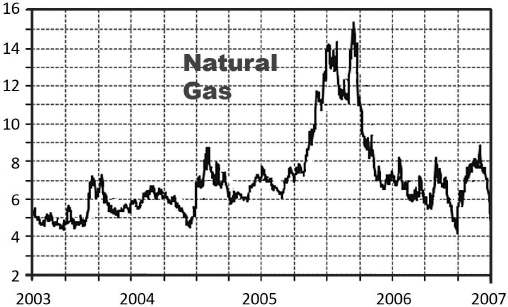

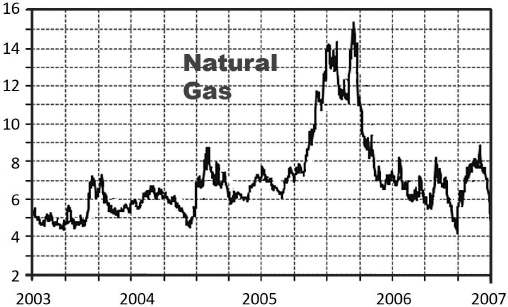

Weather and hedge fund speculation drove up natural gas prices from 6 to above 15 USD.

These extreme weather events, as well as relatively constant demand during the winter months, led to increasing price volatility and, in some cases, substantial price spikes for energy, especially natural gas. While the price of gas traded between 6 and 7 USD during 2004 and the first half of 2005, the hurricane season drove up gas prices to more than 15 USD in December. Production disruptions dragged on for months, but the warm winter, the absence of major storms, and a greater number of imports dampened the effect on the price level of natural gas in 2006.

Compared to their all-time high that year, benchmark natural gas prices in New York lost around two-thirds of their value. In September natural gas was trading near 4 USD. The huge fluctuations in price made natural gas interesting for short-term-oriented traders, but natural gas’s future contract curve offered an even more interesting investment opportunity. Speculation on the change of price differences between different contract maturities is a popular trading strategy, especially by hedge funds: Traders enter long and short positions in the same commodity simultaneously, and the trade is based on an expansion or narrowing of the price differences, that is, a change in the steepness of the term structure.

Some Thoughts on Natural Gas

Natural gas is one of the most important sources of energy in the United States, with a market share of almost 25 percent. Home heating, electricity generation, and other industrial applications together make up nearly 80 percent of its use. But the need for heat, which accounts for 20 percent of total demand, is very seasonal: There’s high demand in the winter months, less during the summer.

Natural gas production in the United States is focused in Texas, the Gulf of Mexico, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Louisiana. Texas and the Gulf region together contribute more than 50 percent of domestic output. Another 15-plus percent of total US natural gas consumption is imported from Canada or imported in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Natural gas is traded on NYMEX under the symbol NG and the current contract month in USD per 10,000 MMBtu (1 MMBtu equals 26.4 cubic meters of gas, based on an energy content of 40 megajoules/m3).

In 2006 the two top hedge fund investors in the US natural gas market were Brian Hunter, head of energy trading at Amaranth Advisors, a fund worth 9 billion USD, and Robert “Bo” Collins, chief executive of MotherRock, which oversaw about 400 million USD. The Mother Rock Energy Master Fund, which launched in December 2004, returned 20 percent to its investors in 2005.

Figure 18. Natural gas prices in USD/MMBtu, 2003 to 2007, New York Mercantile Exchange. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

Some investors at the time were aware that Collins and Hunter held opposing positions in March–April and October–January natural gas contracts. In July 2006 the price difference between the gas futures for March and April 2007 reached 2.60 USD. Hunter’s investment decisions assumed that the difference would increase due to the upcoming cold season. In contrast, MotherRock was betting on a correction in the price spread.

Who Is Brian Hunter?

Born in 1975, Brian Hunter is a Canadian mathematician and hedge fund manager. From 2001 to 2004, he worked at Deutsche Bank in New York. There, in 2001 and 2002, he achieved a profit of 17 and 52 million USD by trading natural gas futures. However, after losses of more than 50 million USD in just one week, Hunter was released from his job. He moved on to Amaranth.

Hunter became a legend on Wall Street by earning more than 1 billion USD speculating on natural gas prices after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. By August 2006 he had achieved a profit of about 2 billion USD. Within a week, however, he had lost three times that, causing serious problems for Amaranth. After his separation from the company, Hunter went on to found a new hedge fund in 2007.

Amaranth, with about 360 employees, had begun as a company that focused on convertible arbitrage. As those profit opportunities dwindled, it moved on to the energy sector. The firm dominated US natural gas trading on financial markets such as the NYMEX and the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), as it bought and sold thousands of contracts, sometimes even tens of thousands, on a daily basis. Amaranth held about 100,000 natural gas contracts in one month, which accounted for about 5 percent of the total annual gas consumption of the United States. On the New York Stock Exchange alone, Amaranth controlled 40 percent of all outstanding contracts for the 2006–2007 winter season (October–March) and more than three-quarters of all outstanding November futures contracts.

Amaranth Advisors and MotherRock had opposite guesses on which way the market would move.

In June and July 2006, erratic natural gas price movements caused massive losses in the MotherRock Energy Master Fund. Earlier, the US Department of Commerce had reported a 12 percent increase in gas inventories. As a result, the gas price dropped by 12 percent within a week. The redemption of shares by investors aggravated MotherRock’s distress, which increased its losses to more than 200 million USD. However, the hedge fund’s high losses were not primarily due to a “normal” price decline. A subsequent Senate investigation confirmed that the sheer volume of Amaranth purchases of March contracts and sales of April contracts had distorted the price spread of natural gas, which moved up by more than 70 percent by July 31, 2006. MotherRock’s position worsened to the point where the fund was unable to meet its margin requirements. The fund collapsed, and positions were wound up in August 2006. Brian Hunter had triumphed, but his victory would be short lived.

In late summer, natural gas prices began a downward spiral. The price of natural gas on the NYMEX, with delivery in October, dropped from 8.45 USD in July to below 4.80 USD in September, the lowest price of the previous two and a half years. The difference between futures contracts maturing in March 2007 and April 2007 moved from a high of nearly 2.50 USD in June to below 50 US cents in September—a plunge of around 75 percent!

Figure 19. Price spread between natural gas March and April 2007 delivery, in USD/MMBtu, New York Mercantile Exchange. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

At the end of August, Amaranth held approximately 100,000 contracts in both the September and October futures on the long and short sides. Taken together, these represented enormous positions, because the movement of only 1 US cent on 100,000 contracts meant a change in value of about 10 million USD. The sheer size of the trades caused significant price movements in natural gas and its future term structure, that is, the price relationship of the different maturities.

Figure 20. Future Term Structure of natural gas in USD/MMBtu, 2010, New York Mercantile Exchange. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

The total positions of the fund added up to approximately 18 billion USD. The 60-cent increase in September contracts and the associated drop in the October–September price spread meant a huge loss for Amaranth.

On August 29 the profit-and-loss calculation showed a one-day depreciation of natural gas valuation of just under 600 million USD. The next day’s margin obligations would be even worse: They rose to 944 million USD, due to further price depreciation. Two days later Amaranth’s margin commitments were in excess of 2.5 billion USD. A week later, on September 8, the hedge fund’s obligations exceeded 3 billion USD.

Amaranth’s total positions added up to 18 billion USD. In September the fund’s margin commitments rose to more than 3 billion USD.

With the price volatility of energy markets remaining high, and because of the cumulative losses, concerns were mounting at Morgan Stanley (one of Amaranth’s important investors, along with Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank), which forced the fund to return money.

Funds under management at Amaranth fell from 9 to 4.5 billion USD in just a week. Founder Nicholas Maounis told his investors in a letter that the company would drastically reduce its positions due to the price fluctuations in the US gas market, and that investors could anticipate losses of 35 percent by the end of the year, even though four weeks earlier the fund had posted a 26 percent profit.

Amaranth got its name from the Greek word for “imperishable,” but it was now painfully clear that the firm’s profits were anything but. In addition to individual investors, injured parties included umbrella hedge funds of Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, and Deutsche Bank. On July 25, 2007, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission condemned Amaranth and Brian Hunter for attempted price manipulation of the natural gas market. Hunter, who had left Amaranth, had already established a new hedge fund—Solengo Capital Advisors.

When Amaranth collapsed in September 2006, investors were told redemptions would be temporarily suspended. Ten years after the blowup, in 2016, Amaranth investors were still waiting to get their money back.

Key Takeaways

•Energy markets were a hot topic in 2005–2006. The price of natural gas climbed from 6 to more than 15 USD, but in late summer the market turned sour and a downward spiral began. In September 2006 natural gas fell below 5 USD.

•Brian Hunter built a position of 18 billion USD in natural gas. By August 2006 his trades had earned him 2 billion USD. But then the market turned against him. Within weeks he had lost 6 billion USD, and Amaranth Advisors collapsed in September 2006.

•The demise of Amaranth Advisors shook the financial industry. It was the biggest hedge fund collapse since the downfall of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998 and investors haven’t been paid back yet.